|

|

|

|

In the 1960s a group of dedicated amateurs formed the

Loch Ness Investigation Bureau to keep a constant

vigil on the loch.

In the 1960s a group of dedicated amateurs formed the

Loch Ness Investigation Bureau to keep a constant

vigil on the loch.

|

Birth of a Legend

Part 2 |

back to part 1

In the 1950s, a local doctor named Constance Whyte began

collecting these eyewitness accounts, along with sketches of

what the people had seen, finally publishing them in 1957 as a

book entitled More Than a Legend. Noting that many of

her friends had been subjected to ridicule and contempt, Whyte

said her goal in writing the book was "the vindication of many

people of integrity who had reported honestly what they had

seen in Loch Ness." (To hear recent personal anecdotes, see

Eyewitness Accounts.)

Whyte's book inspired a new generation of monster hunters,

including Tim Dinsdale, who on his first visit to the loch in

1960 took an intriguing film of something moving across the

loch—and promptly gave up his career as an aeronautical

engineer to devote his life to pursuing the monster. The next

year, a group of dedicated amateurs formed the Loch Ness

Investigation Bureau, keeping a constant vigil on the loch

from an observation post on the northern shore.

In 1987, Operation Deep Scan, the most ambitious

sonar survey of Loch Ness, found three unexplained

underwater targets.

In 1987, Operation Deep Scan, the most ambitious

sonar survey of Loch Ness, found three unexplained

underwater targets.

|

|

But perhaps the most important effect of Whyte's book was to

turn the tide of public opinion. Long dismissed as fodder for

"silly season" press reports, Nessie was finally considered a

subject worthy of serious scientific investigation. In the

span of a decade, beginning in 1958, four separate expeditions

were launched, first by the BBC, then by three respected

British universities: Oxford, Cambridge, and the University of

Birmingham. Rather than scanning the surface with binoculars

and cameras, as the amateur investigators had, these

expeditions came equipped with sonar, a military technology

that used sound to search the underwater environment. Though

the expeditions found nothing conclusive, in each case the

sonar operators detected large, moving underwater objects they

could not explain. (To learn how sonar works, see

Experiment with Sonar.)

|

Taken in 1975, this photograph, which seems to show

the flipper of an aquatic creature, helped rekindle

interest in the monster.

Taken in 1975, this photograph, which seems to show

the flipper of an aquatic creature, helped rekindle

interest in the monster.

|

The use of technology to search the loch reached a new level

in the 1970s, when a series of expeditions was sponsored by

the Boston-based Academy of Applied Science, whose members

included many technically skilled people with ties to MIT. The

Academy's approach was to set a trap for the monster by

combining sonar and underwater photography for the first time.

Under the leadership of Robert Rines, a lawyer trained in

physics, the team pointed a sophisticated form of sonar,

called side scan sonar, out into Loch Ness from a point near

the shore. Nearby they placed an underwater camera taking

pictures every 45 seconds as a strobe light illuminated the

depths with a bright flash. The system paid off one night in

1975. At the same moment the sonar was registering a large,

moving object, the underwater camera was taking pictures of an

object that looked, after development and computer

enhancement, like the flippers of an aquatic creature.

Rines' discovery won the support of two reputable scientists:

Harold "Doc" Edgerton, the legendary MIT scientist who had

invented side scan sonar and strobe photography; and Sir Peter

Scott, one of Britain's most respected naturalists. With

Edgerton and Scott behind him, Rines was given an opportunity

to present his evidence at a hearing at the House of Commons

in London. Never had the possibility of the Loch Ness Monster

been taken so seriously.

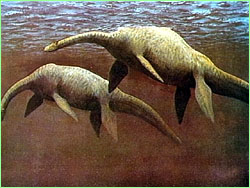

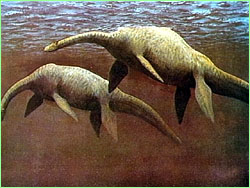

This painting by Sir Peter Scott, a respected British

naturalist, helped create the popular image of Nessie

as an ancient reptile called a plesiosaur.

This painting by Sir Peter Scott, a respected British

naturalist, helped create the popular image of Nessie

as an ancient reptile called a plesiosaur.

|

|

Almost immediately, however, critics began to raise questions

about the evidence. Could the suggestive sonar traces be the

result of human error? Had the flipper photos been altered to

improve their appearance? Just as damaging to Rines' case was

Peter Scott's bold pronouncement about the identity of the

creature. Based on the flipper photos and the eyewitness

sightings, Scott concluded that Nessie was a plesiosaur, an

ancient reptile that was thought to have gone extinct along

with the dinosaurs some 65 million years ago. The idea was

just too far-fetched for professional zoologists to take

seriously.

Although zoologists have yet to conduct the full-scale

investigation Rines hoped to trigger, the loch continues to

yield intriguing sonar hits. In 1987, an expedition called

Operation Deep Scan used a flotilla of 20 sonar-equipped boats

to sweep the loch with a curtain of sound; the operation

yielded three underwater targets that could not be explained.

In the early 1990s, the BBC's Nicholas Witchell helped

organize Project Urquhart, the first extensive study of the

loch's biology and geology. Although they weren't looking for

monsters, the expedition's sonar operators detected a large,

moving underwater target and followed it for several minutes

before losing it. And during the 1997 expedition featured in

NOVA's Loch Ness film, Rines and his longtime colleague

Charles Wyckoff detected yet another puzzling underwater

target. According to the expedition's sonar expert, marine

biologist Arne Carr, it was a moving target, appeared to be

biological in nature, and was about 15 feet long—the

size of a small whale.

Continue

Fantastic Creatures

|

Birth of a Legend

Eyewitness Accounts

|

Experimenting with Sonar

Resources |

Transcript

| Site Map |

Loch Ness Home

Editor's Picks

|

Previous Sites

|

Join Us/E-mail

|

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

©

| Updated November 2000

|

|

|

In the 1960s a group of dedicated amateurs formed the

Loch Ness Investigation Bureau to keep a constant

vigil on the loch.

In the 1960s a group of dedicated amateurs formed the

Loch Ness Investigation Bureau to keep a constant

vigil on the loch.

In 1987, Operation Deep Scan, the most ambitious

sonar survey of Loch Ness, found three unexplained

underwater targets.

In 1987, Operation Deep Scan, the most ambitious

sonar survey of Loch Ness, found three unexplained

underwater targets.

Taken in 1975, this photograph, which seems to show

the flipper of an aquatic creature, helped rekindle

interest in the monster.

Taken in 1975, this photograph, which seems to show

the flipper of an aquatic creature, helped rekindle

interest in the monster.

This painting by Sir Peter Scott, a respected British

naturalist, helped create the popular image of Nessie

as an ancient reptile called a plesiosaur.

This painting by Sir Peter Scott, a respected British

naturalist, helped create the popular image of Nessie

as an ancient reptile called a plesiosaur.