|

|

Vince Lee's Uphill Battle by Vincent R. Lee In the spring of 1998, I was asked to take part in the filming of the NOVA film "Easter Island," during which experts examined hand methods for moving and erecting moai, the huge stone statues for which the island is famous.

The plan was to move a nine-ton concrete moai overland onto a fieldstone "ahu" or platform and leave it standing erect with a stone topknot or "pukao" balanced on its head. Most ahus are effectively seawalls, accessible only from their inland sides. Long columns of pullers could not possibly have dragged their moai into place atop these platforms without falling off the back into the ocean. Fortunately, the NOVA ahu was inland and a large gang of pullers on the open ground beyond its "seawall" was able to drag the sled into place. Nevertheless, it was abundantly clear that the final movement up onto a coastal ahu wasn't just an unsolved detail: It was the crux of the problem, since with enough people almost anything could be dragged across open country.

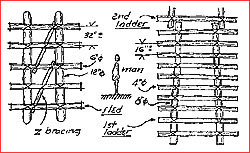

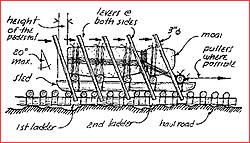

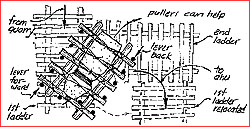

All of this added up to a whole new way of looking at moving big rocks. Like many others, I had been distracted by scenes from antiquity showing giant monoliths being pulled on sleds. Now I knew that the ancients must have used another method altogether in places with no room for all those long columns of pullers. Needed was a much smaller workforce able to do the same job, and as Archimedes pointed out 22 centuries ago, there was only one way to do that. Levers were the only tools most pre-industrial people like the Rapanui had for multiplying the muscle power of a man. By clever application of the idea, one leverman might do the work of five or even 10 conventional laborers. Used to maneuver huge stones in confined places, levers would greatly reduce the work force needed and, more to the point, the space it required. In theory, everyone could push from alongside, behind, or atop the rock, eliminating the need for any pullers at all—exactly what was needed to get a large moai up onto a high, coastal ahu. What if moving big rocks was like moving ships? Mediterranean galleys had sails for favorable winds and open water, and oars for close quarters and auxiliary power. A nautical analogy seemed especially appropriate on Easter Island. Didn't the islanders' ocean-going canoes, like the galleys half a world away, use both sails and paddles? At one point in the NOVA film, the team hauled a heavy outrigger up over the rocky shoreline on a Polynesian "canoe ladder," a frame identical to the leapfrogging sliders I'd earlier envisioned as the ideal roadway for moving moai. In a flash, an entirely new and surprisingly simple alternative transport method came together: a lever-friendly sled pulled easily over lever-friendly canoe ladders as much as possible, but turned, rotated, or nudged slowly forward by levermen wherever necessary (see Figure 1). Simple as the idea may seem, the devil, as always, is in the details. The leapfrogging ladders promise a smooth, easily leveled, and effectively endless working surface with as many firm purchases for the toes of the levers as possible. The latter is especially important, since slippage against the ground greatly reduces lever efficiency, a common problem unless something is done to prevent it. The sled, too, offers as many places to push against as possible but spaces them to optimize placement of the levermen.

As critical as the force urging the sled forward is the frictional force holding it back, and every effort to smooth and grease the contact surfaces reduces the required crew size. All lashings have to be neatly done and recessed or otherwise prevented from hanging up, and the sled runners need to be beveled at both ends to ride smoothly onto the sliders before and after the required 180-degree rotation of the moai. One would rotate the sled with this system much as one would rotate a rowboat or canoe, by levering one side forward and the other back. It is important that the sled runners not get parallel to the sliders and fall into the gaps between them, though levering forward onto ladders set 90 degrees from one another avoids the problem (see Figure 3). Continue: A Hasty Experiment Vince Lee's Uphill Battle | NOVA Moves a Megalith | How Big Were They? Move the Moai | Explore Easter Island | Secrets of Easter Island | Resources | Transcript Medieval Siege | Pharaoh's Obelisk | Easter Island | Roman Bath | China Bridge | Site Map Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

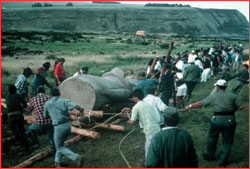

At the Easter Island site, the NOVA team drags the

concrete moai on its specially designed sled.

At the Easter Island site, the NOVA team drags the

concrete moai on its specially designed sled.

Figure 3: Sketch of scheme to rotate moai

Figure 3: Sketch of scheme to rotate moai