|

|

|

|

The Stem-Cell Debate

Part 2 |

Back to Part 1

Moral seasoning

Regarding the second issue I mentioned above - that of

derivation of PSCs—presuming that at least initially

such stem cells will likely come from discarded human

embryos from IVF clinics, then research or no research, the

embryos will be destroyed. This means they will be thawed

and eventually incinerated or otherwise discarded. British

infertility clinics, in the course of performing their

legally mandated duty of discarding 3,300 unwanted or

unclaimed embryos, are reported to have thawed and

administered a few drops of alcohol to each embryo before

incinerating them. It would seem that even for those who

oppose embryo destruction, the morally relevant conduct here

is the destruction, not how it is accomplished. Once one has

set about destroying an early embryo, it seems immaterial

whether this is done by thawing and allowing it to die in a

petri dish, by dropping it into a lethal solution, or by

using a micropipette to disaggregate it.

|

No one denies that early embryos lack sensory organs

or tissues. They cannot suffer pain.

|

No one denies that early embryos lack sensory organs or

tissues. They cannot suffer pain. Their moral worth, if any,

resides in their potential for further development. The

"wrong" here (if there is any wrong at all) is the ending of

that potential, not how it is ended. Downstream

researchers may thus be involved in encouraging clinicians

and others to adopt a particular method of embryo

destruction, but that is morally unimportant. They are in no

way involved in encouraging the destruction itself, which

will occur in any case. That is, downstream researchers

would merely be encouraging adoption of a morally neutral

method that is most likely to produce some benefit from an

otherwise unavoidable situation of loss.

If ES cells come from rejected IVF embryos slated

for imminent destruction, Green feels that the

potential benefits of stem-cell research outweigh

right-to-life concerns.

If ES cells come from rejected IVF embryos slated

for imminent destruction, Green feels that the

potential benefits of stem-cell research outweigh

right-to-life concerns.

|

|

Working through these thoughts, I had no illusions that this

approach would end the controversy over ES cell research.

Some people would continue to abhor even the most remote

connection with what they regarded as evil deeds. Others

would see symbolic issues within these debates that

threatened the sanctity of human life. They would see the

involvement of researchers in the killing of a form of human

life as a dangerous precedent that outweighed the benefits

of ES cell research.

Though I appreciated these concerns, I did not see them as

outweighing the possible benefits of ES cell research. I

believed that many people who hold a different view of the

early embryo's status than I do could share my conclusions

about using embryos that would otherwise be destroyed. My

aim was to develop a position that could attract enough

support from a middle ground to shape public policy. The

challenge was to understand the issues sufficiently to

determine which analogies, precedents, or illustrations best

conveyed their underlying logic. Once that determination was

made, one could identify those arguments most likely to

convey the issues honestly and effectively to a larger

audience.

|

The image of researchers dissecting tiny human

beings should not be allowed to dominate the

discussion.

|

Simultaneously, one could better understand the force of

one's opponents' views and how to respond to them. The image

of researchers dissecting tiny human beings should not be

allowed to dominate the discussion. The public had to

understand that the key issue was whether spare embryos

would be used for valuable research that could save human

lives or would merely be thrown away. This was not a matter

of countering one emotionally evocative image with another.

Rather, it was an attempt to articulate the real nature of

the choices and their most likely moral implications.

Down the road

Future developments may erode the emphasis on spare embryos

implicit in the use-versus-derivation distinction. As I have

argued, the moral logic of separating use from derivation

rests on the fact that the needed embryos can come from the

population of those embryos left over from infertility

procedures that will otherwise be destroyed. However, we can

already imagine a future in which it may be desirable

deliberately to create embryos in order to produce

autologous pluripotent stem cell lines. This is the prospect

I sketched earlier of using a somatic cell from an

individual to produce an embryo (via somatic cell nuclear

transfer technology), and from this embryo, a

histocompatible ES cell line for cell-replacement

therapy.

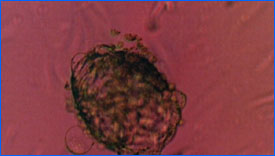

At the moment, the notion of creating new ES cell

lines using human embryos fashioned by means of

"therapeutic cloning" is fraught with moral and

technical uncertainties.

At the moment, the notion of creating new ES cell

lines using human embryos fashioned by means of

"therapeutic cloning" is fraught with moral and

technical uncertainties.

|

|

Before "therapeutic cloning" of this sort becomes a reality,

and certainly before it merits federal research support,

many questions will have to be asked. Is it really not

possible to avoid this alternative by manipulating immunity

factors in existing pluripotent stem cell lines produced

from spare embryos (research that could be done with federal

dollars)? Does the actual bench research in this area need

federal support and oversight, or is it something that can

be accomplished effectively with private funding? And if

this possibility becomes a clinical therapy, will it need

federal support, or can it be offered as a purchased

clinical service?

The answers to these questions are by no means evident. If

cell-replacement therapies using deliberately created

embryos prove highly successful, we may also have to

consider issues of federal funding beyond the research

context, in the area of clinical services. Would it be just

to deny Medicaid or Medicare recipients access to these

therapies merely because other citizens morally object to

them?

|

Would it be right, Green asks, to deny, say, a

Medicaid patient access to cell-replacement

therapies just because some people may morally

object to them?

Would it be right, Green asks, to deny, say, a

Medicaid patient access to cell-replacement

therapies just because some people may morally

object to them?

|

Fortunately, these are questions for the future. I introduce

them here to illustrate how ongoing experience can force a

rethinking of moral conclusions from one period to the next.

This is exactly what happened with fetal tissue

transplantation research, support for which has been

reinforced by increasing clinical successes and the efficacy

of morally sound regulations.

I must stress that there are two things I am

not saying in indicating the importance of ongoing

experience and the possibility of revising our conclusions.

First, I am not suggesting that we should advocate the least

offensive research initiatives now as a political device for

expanding these initiatives later. I am not a political

scientist and have no idea whether this is the best way to

proceed. I am making a moral, not a political, argument. It

is respect for others, not political efficacy, that requires

the use of the least offensive means needed at each stage of

research.

Second, I am not suggesting that success makes something

that is wrong right. I personally do not believe that human

embryo research, including the deliberate creation of

embryos for valid research or clinical purposes, is wrong,

but I acknowledge that many people do. I am not saying that

the mere fact of scientific or clinical success will

convince these people otherwise or prove them wrong.

Moral reasoning must always be in conversation with

human experience.

|

|

I am saying that moral reasoning must always be in

conversation with human experience. Because so many aspects

of moral decision require difficult balancing judgments

often based on uncertain predictions about future harms or

benefits, it is very important to stay in touch with moral

realities as they evolve "on the ground." It may be that all

the promises of human embryo or pluripotent stem cell

research will prove to be fruitless. In that case, the

urgency of this research and the justification of continued

federal funding for research will decline.

Conversely, the clinical successes may be enormous. They may

also spur new techniques for producing pluripotent stem cell

lines that reduce or minimize the need to destroy embryos.

In that case, those currently opposed to these research

directions may find themselves altering their opposition to

some forms of this research. Remaining open to experience

does not mean sacrificing principles to success. It merely

expresses the wisdom that as human beings we are not

omniscient or unerringly right in our moral judgments.

|

|

Dr. Ronald M. Green is The Eunice and Julian Cohen

Professor for the Study of Ethics and Human Values,

Chair in the Department of Religion, and Director of

the Ethics Institute at Dartmouth College. In 1996

and 1997, he served as the founding Director of the

Office of Genome Ethics at the NIH's National Human

Genome Research Institute. This article was adapted

from Green's book,

The Human Embryo Research Debates: Bioethics in

the Vortex of Controversy

(Oxford University Press, 2001), with kind

permission of the publisher.

|

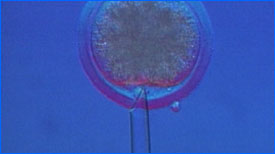

Photos: (1-2, 6-8) WGBH/NOVA; (3-4) Courtesy of Dr.

Thomson and Dr. Gearhart; (5) Corbis Images; (9) Courtesy

of Dr. Green.

Watch the Program

|

The Stem-Cell Debate

|

Windows on the Womb

Great Expectations

|

How Cells Divide

|

How is Sex Determined?

Resources

|

Teacher's Guide

|

Transcript

|

Site Map

|

Life's Greatest Miracle Home

Search |

Site Map

|

Previously Featured

|

Schedule

|

Feedback |

Teachers |

Shop

Join Us/E-Mail

| About NOVA |

Editor's Picks

|

Watch NOVAs online

|

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

©

| Updated November 2001

|

|

|

|