|

|

|

Part 2 | Back to Part 1 NOVA: If DNA fingerprinting is so seemingly perfect, are you taking the human element out of it? Chernoff: No, I don't think so. Portions of the science are so exact that it makes us really focus on the human aspect of it. We know that the science of identification—comparing one person's DNA with another person's DNA—approaches a near certainty. I think it's one in three billion for including or excluding someone. And so that part of speculation or inference is really eliminated. But it forces us to focus on other factors, including how evidence is collected. There's plenty of room for someone to make a mistake in the collection of data, and there's plenty of room for human deviousness. You know, if you're not comparing the right substances, if you're not being square with your test results, it doesn't matter how good the process is. So the human element is still there. This folds into the daunting aspect as well. One of the things I learned is that, for example, if you and I shake hands, some of my DNA rubs off onto your hand, and some of the cells from your hand rub off onto mine. If I then go and pick up a telephone, your cells may end up on that telephone, and if there's a DNA match with cells on that phone, someone might think that that is evidence that you touched that telephone. Whether that's good science or bad science, or a good conclusion or a bad conclusion, it creates a real problem for us. If it is true that evidence could be admitted that your cells are on that phone, it means that the technique is not really as perfect as it may appear, because you can get cells transferred so easily. If it's not true, and it's all smoke and mirrors, then it's smoke and mirrors that somebody can blow at valid DNA evidence, and it can trivialize it when it shouldn't. That's a little daunting as to how we would handle that kind of issue in court. NOVA: What other scientific techniques or procedures are increasingly playing a role in court cases? Chernoff: Well, pharmacology and psychopharmacology—the use of drugs, and how they affect people. I don't think that has much to do with DNA, although it might, if you compare how drugs work on different people. I'm sure there may be some genetic aspect to that. But whether or not a person who is incompetent for trial, or incompetent to plead guilty, can be made competent at least temporarily by the administration of certain drugs—that's a very big issue for us. Also whether or not you can mandate that someone take a particular legal drug that might make the person more stable, and thus make you more willing to take a chance on them as far as sentencing is concerned. Then, of course, how do you enforce that in the community, to make sure that a person takes that drug? I think that's a real challenge for us, to understand the pharmacology of legal and illicit drugs. A lot of people that we see who come before us on the criminal side are constantly under the influence of a drug, or they've been under the influence, or they will be under the influence.

Chernoff: Yes, I held a hearing on polygraph testing and found it to be somewhat valid, somewhat invalid. I carved out a mechanism for handling it in court that I thought made perfect sense, but the Supreme Judicial Court disagreed. Nevertheless, it was a wonderful experience for me to look at the entire science behind the polygraph and determine whether it should go or not. More recently, I had to rule about testimony concerning the blood/brain barrier, specifically on the issue of whether or not myotrauma can exacerbate multiple sclerosis. The Multiple Sclerosis Society says no, a Harvard doctor says yes. The question was: Should those competing experts be able to testify before a jury? I ruled that they could (and the jury ruled against the plaintiff in the case). But I had to rule on the science. Whether or not the theory was correct or not is not the issue; it's whether or not there's validity to the theory and reliability to the method. And whether the expert's right or wrong is not for me but for the jury to decide. There's another interesting thing I took away from the two-day program at the Whitehead Institute. We as judges have focused on DNA as a law-enforcement technique to either include or exculpate an individual, but we quickly learned in our program that that's just a fragment of the science. What it's really going to yield, we hope and expect, is the promise for curing disease and making diagnoses and relieving human suffering. This wonderful DNA matching is a nice spin-off for law enforcement, but it's the rest of the science that really has more importance in the long run for human beings.

Chernoff: We've been talking with the Whitehead people about a joint training program for scientists and judges, in which we would bring them this time into our laboratory, the courtroom, and show them how science is treated there. We would have them school us on science, and we would school them on legal procedure and on how validity and reliability are resolved in a court of law. NOVA: Is this kind of judges-go-to-school program unusual in the U.S. judicial system? Chernoff: It is. I've been told that, aside from the Whitehead Institute, there are only two programs in this country. The Cold Spring Harbor Lab on Long Island has offered an educational opportunity to the judiciary in New York, which focuses on some of the issues we learned about. And George Washington University in Washington, D.C. has a couple of day programs for judges, though I don't know if they have the laboratory component. One of my colleagues, who like me is on the faculty of the Judicial College in Nevada, was out there the week after the Whitehead program, and people there had learned of the program and were very interested in learning more. They would like to hook up with a college or university in California to try to bring some of their scientists to the Judicial College to school judges. So I think maybe we started something here. Photos: (2) Sam Reese Sheppard Chronology of a Murder | Science in the Courtroom Create a DNA Fingerprint | 3-D Mug Shot | Cleared by DNA Resources | Transcript | Site Map Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

Even such a simple act as shaking hands can

complicate the presentation of genetic evidence, since

an individual's DNA can be transferred that easily.

(In the photo above, Dr. Sam Sheppard is at right.)

Even such a simple act as shaking hands can

complicate the presentation of genetic evidence, since

an individual's DNA can be transferred that easily.

(In the photo above, Dr. Sam Sheppard is at right.)

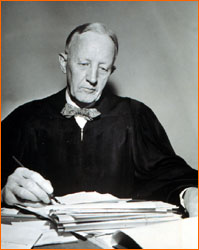

To a degree unimagined by the likes of Edward

Blythin, who judged Sam Sheppard in 1954, judges today

must be conversant in a wide range of fields, from DNA

fingerprinting to psychopharmacology.

To a degree unimagined by the likes of Edward

Blythin, who judged Sam Sheppard in 1954, judges today

must be conversant in a wide range of fields, from DNA

fingerprinting to psychopharmacology.

Judge Chernoff (here shown running a road race) on

his recent initiative to inculcate fellow judges in

the ways of DNA fingerprinting: "I think maybe we

started something here."

Judge Chernoff (here shown running a road race) on

his recent initiative to inculcate fellow judges in

the ways of DNA fingerprinting: "I think maybe we

started something here."