Bringing Home MIAs by Peter Tyson

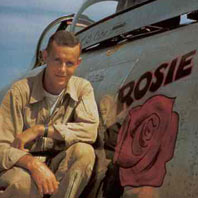

On September 16, 1952, U.S. Air Force Captain Troy Cope and

the F-86 Sabre jet he was flying disappeared while in a

dogfight with Soviet pilots. They were battling over "MiG

Alley," an infamous stretch of airspace above North Korea's

border with China. Search-and-rescue teams found no trace of a

crash site, and for half a century his family had no idea what

had happened to him.

Then, in 1995, a U.S. businessman who was visiting a small

military museum in northeast China noticed several American

dog tags on display. One of them proved to be Captain Cope's.

Later, as part of their ongoing investigations into American

MIAs, the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office

(DPMO) in Washington discovered detailed notes in a Russian

archive in Moscow of a joint Soviet-Chinese investigation

decades before into the crash site of a USAF Sabre in China.

The plane had gone down just across the Yalu River from North

Korea. The account was so thorough that it identified not only

the village where the crash had occurred but the very

farmyard.

In 2004, DPMO led an excavation at the site. Along with his

plane, Captain Cope's remains were unearthed and later

identified. "We actually went into the lab to where my dad's

stuff was laid out," says Cope's son Danny in NOVA's "Missing

in MiG Alley." "Small piled ... fragments of ... bones," he

added, haltingly. "Being with the remains and being allowed to

touch them and—that was just beyond words. Can't

describe it...."

Keeping the promise

Such an effort is just one piece of a much larger effort that

has dozens of U.S.-sponsored search-and-recovery expeditions

working worldwide each year. Many of them meet with success.

From 2000 to the fall of 2007, for example, forensic

anthropologists working for the Joint POW/MIA Accounting

Command (JPAC), which does the actual recovery and

identifications, identified the remains of more than 575

American service personnel. These are all young men who lost

their lives while serving their country in World War II or any

conflict since—men who have been missing in action for

decades, their families never knowing what happened to them.

"The men and women who ... head to war today ... are deserving

of our every effort to bring them home again, safely

and alive," Ambassador Charles Ray, the Deputy

Assistant Secretary of Defense for POW/Missing Personnel

Affairs, told an audience of Special Forces veterans in

September 2007. "Our motto is Keeping the Promise. Today, that

service member, his family, all those from Desert Storm, Iraqi

Freedom, the Vietnam War, the Cold War, the Korean War, and

World War II ... all await answers from their government. And

if I have anything to do with it, they shall get those

answers...."

The United States wants its dead back so fiercely that it

spends more than $105 million a year trying to find, retrieve,

and identify them as well as give them a proper burial with

full military honors. More than 600 military and civilian

personnel work full-time on the POW/MIA effort. Their task is

staggering, as the combined total of U.S. service personnel

from World War II to the present listed either as "missing in

action" or "killed in action, body not recovered" exceeds

88,000. But DPMO is not daunted, and it has achieved an

enormous amount since its founding in 1993.

In the field

DPMO's first priority is to bring back live American POWs.

Even today, reports of captive Americans occasionally come out

of Korea, Russia, and Southeast Asia. The U.S. actively looks

into all such reports. Vietnam, for example, has agreed to let

DPMO officials conduct investigations, on short notice, of

so-called "live sightings"—cases in which someone

reports having seen an American POW or MIA alive. In recent

years, investigators have carried out about 120 on-site

investigations or reported live sightings in Vietnam, Laos,

and Cambodia. All of these sightings have proven to be false

alarms, however, and to date the U.S. has found no evidence

that any Americans are still being held as POWs in any of

these countries or regions.

"Here's the dog tag of the serviceman, and we'll take you to

where his remains are buried."

DPMO's second priority, and the one that the bulk of its

resources go toward, is to find, bring back, and put names to

the remains of deceased American personnel. The

search-and-recovery process for a missing military service

member or civilian often begins with archival research in the

U.S. or in the country where a serviceman is believed to have

been lost. Sometimes American authorities will contact a

foreign government about investigating, say, an aircraft crash

site; sometimes foreign officials will contact their

counterparts in the U.S. with newly uncovered evidence.

It even happens sometimes that former combatants or their

families will suddenly come forward with new information. "In

Vietnam, we've had people who've walked into either the

American Embassy or our POW/MIA detachment there in Hanoi,

just walked in with a dog tag or a fragment of bone," says

DPMO's Larry Greer. "They'll say, 'My grandfather has had this

for years, and we want to do what we can for the American

family. Here's the dog tag of the serviceman, and we'll take

you to where his remains are buried.'"

DPMO or other agencies negotiate with the relevant government

to do so-called joint field activities. Each of these forays

can last 45 days and may involve more than 100 individuals.

Team members interview witnesses and inspect sites. If they

decide an excavation is called for, the Hawaii-based Central

Identification Laboratory, which is part of JPAC, arranges for

a team like that deployed to China to undertake the work.

These teams consist of members from the four service branches.

An Army or Marine captain or major leads the crew, which

typically includes a senior noncommissioned officer, two to

four mortuary specialists, and at least one civilian forensic

anthropologist or archeologist. There is also an interpreter,

photographer, medic, and, where needed, experts in explosive

ordnance disposal. In some rare cases, immediate family of

those sought may visit the excavation site at their own

expense, but such visits are discouraged due to the hazards of

unexploded ordnance and, in the tropics, exotic diseases.

The forensic anthropologist is in charge of the excavation. He

or she follows strict procedures, carefully gridding the area

to be excavated, sifting soil through quarter-inch screens to

capture even the smallest bones or artifacts, and taking

numerous documentary photographs. After clearance from the

host country, the team flies any remains of American personnel

back to the U.S. in flag-draped coffins.

In the lab

In the JPAC laboratory, forensic specialists try to determine

the age, sex, and race of individuals. They also look for any

signs of trauma or healed fractures as well as at the

arrangement, number, and other aspects of the deceased's

teeth. Because of the skeletal nature of most remains from

past wars, experts identify many of those whose identities are

restored by comparing their dentition with dental records.

"Mom held on, and within a week after his remains were

identified, she quietly passed away."

In nearly half of all cases, however, testing of mitochondrial

DNA, or mtDNA, is also brought to bear. For that, the

specialists need blood samples from maternally related family

members. DPMO and the military services have an active

outreach program to contact families for this purpose.

Details on artifacts such as personal effects or aircraft

wreckage are also evaluated, as are circumstantial evidence

and eyewitness accounts by, say, surviving crew members or

cooperative former enemy personnel.

Reaching closure

When JPAC specialists ascertain the identity of remains, the

respective military service casualty or mortuary office

contacts the serviceman's family. In most cases, family

members have been awaiting such a call for an excruciatingly

long time. "I've had a number of younger family members tell

me, 'Mom held on because she felt that our loved one's remains

would soon be coming home,'" Greer says. "'And within a week

after his remains were identified, she quietly passed away.'"

Each military service offers the family a choice: Inter their

loved one in Arlington National Cemetery outside Washington,

D.C., or have the individual's remains flown home for a

private burial. Either way, the government pays for the

funeral and accords the serviceman full military honors.

Unidentified remains stay in Hawaii in hopes that JPAC

specialists will eventually succeed in identifying them. They

include more than 850 unknowns from the Korean War who are

buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in

Honolulu. When returned to the U.S. a half century ago, these

remains were treated with a preservative that has interfered

with retrieval of mtDNA samples. But JPAC officials are

hopeful that advances in forensic techniques might someday

solve such problems. "There's no telling what new technologies

might come along," Johnie Webb, JPAC's Deputy to the Commander

for Public Relations and Legislative Affairs, told

The National Amvet magazine in 2000. "We've only had

DNA analysis since 1994, and with it, we have identified

remains that were mysteries to us since the mid-‘80s."

War by war

World War II: By far the greatest percentage of

American MIAs went missing in the Second World War. More than

78,000, or nearly 90 percent of the total number of missing

U.S. servicemen, never returned from this conflict. Many were

lost at sea or buried as unknowns in cemeteries across Europe.

Every year, JPAC identifies more soldiers from World War II.

DPMO and JPAC seek American dead from this war not just in

Europe but around the world. The inaccessibility of a place

where servicemen were lost is not an issue. In November 2000,

for example, JPAC identified the remains of 19 marines

retrieved from remote Butaritari Island in the South Pacific,

where they had died in a battle with Japanese forces in 1942.

Among them was Sgt. Clyde Thomason, the first enlisted marine

awarded the Medal of Honor in World War II.

Korean War: More than 8,100 Americans remain

unaccounted for from the war in Korea; most disappeared in the

North. In an effort to locate as many of them as possible and

bring them home, DPMO has negotiated joint recovery operations

in North Korea since 1996—a remarkable achievement,

considering the U.S. is still technically at war with that

nation. JPAC teams have disinterred more than 225 sets of

remains believed to be those of American soldiers from within

North Korea; 57 of them have been identified so far.

The North Koreans granted permission for U.S. teams to search

for remains around the Chosin Reservoir, scene of some of the

war's most intense fighting. The sites may hold the remains of

more than 1,000 American servicemen. DPMO is also seeking

access to several POW camps along the Yalu River, which forms

the border between North Korea and China. In the spring of

2005, however, the U.S. temporarily suspended remains recovery

operations in North Korea, a suspension that continues.

Scores of people just like Danny Cope are counting on them.

Vietnam War: As of early October 2007, 1,768 Americans

remained unaccounted for from this conflict, including 1,357

from Vietnam, 349 from Laos, 55 from Cambodia, and 7 from

China. Since 1973, teams have repatriated, identified, and

buried on American soil the remains of 877 U.S. service

personnel who had never returned from Southeast Asia.

Recently, and in a remarkable way, JPAC identified the remains

of Air Force Colonel Charles Scharf, who was shot down in

Vietnam in 1965. During the war, Colonel Scharf had sent his

wife Patricia a series of love letters. She saved them for

over 40 years, and JPAC specialists were able to use the DNA

her husband left on them to identify his remains. Colonel

Scharf was buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full

military honors.

"Last known alive" cases—those involving MIAs who are

believed to have survived their initial falling into enemy

hands—are a high priority. The U.S. originally

identified 296 such cases throughout Southeast Asia. Intensive

investigations have shown that 216 are deceased, while the

remains of 68 of them have been located, flown home, and

identified. The work goes on.

Cold War: About 125 Americans are still missing from

the Cold War. Most vanished while flying spy missions along

the Soviet border. A joint U.S.-Russian commission is working

to investigate both American and Russian MIAs from the Cold

War.

Other countries are aiding the search as well. China, for one,

assisted the U.S. with a long-standing Cold War case. It

involved two missing American CIA fliers, whose C-47 plane

crashed in Manchuria in 1952. The Chinese captured two of the

plane's four-man crew and held them until 1971 and 1973,

respectively, but the other two crewmen, Robert Snoddy and

Norman Schwartz, went unaccounted for. During on-scene

investigations at a site in China in 2002, a U.S. team

recommended the site be excavated for possible human remains.

In 2004, a joint JPAC-Chinese team found aircraft debris,

personal effects, and human remains at the site, and the

following year specialists identified the remains of Robert

Snoddy.

Iraq: Remarkably, only one American serviceman is

listed as "missing-captured" from Desert Storm, the first war

with Iraq. He is Navy Captain Michael Scott Speicher, who was

lost on the first night of Desert Storm while flying a combat

mission over Iraq. But one is not too few for DPMO, which

continues to seek his remains. Four American soldiers are

missing-captured from Iraqi Freedom, the current war in Iraq.

The search for them proceeds in the midst of deadly combat.

Fortunately, no American service personnel are currently

unaccounted for from Afghanistan. But one can be sure that

DPMO, JPAC, and other agencies of the U.S. government are

standing by, ready to "keep the promise" if necessary and do

their best to bring back any personnel that go missing,

whatever the cost. Scores of people just like Danny Cope are

counting on them.