Indigenous Artifacts: Understanding the Law

Many indigenous tribal objects raise important legal and ethical questions — are they appropriate to own, or buy, or sell? Multiple laws make a complicated field.

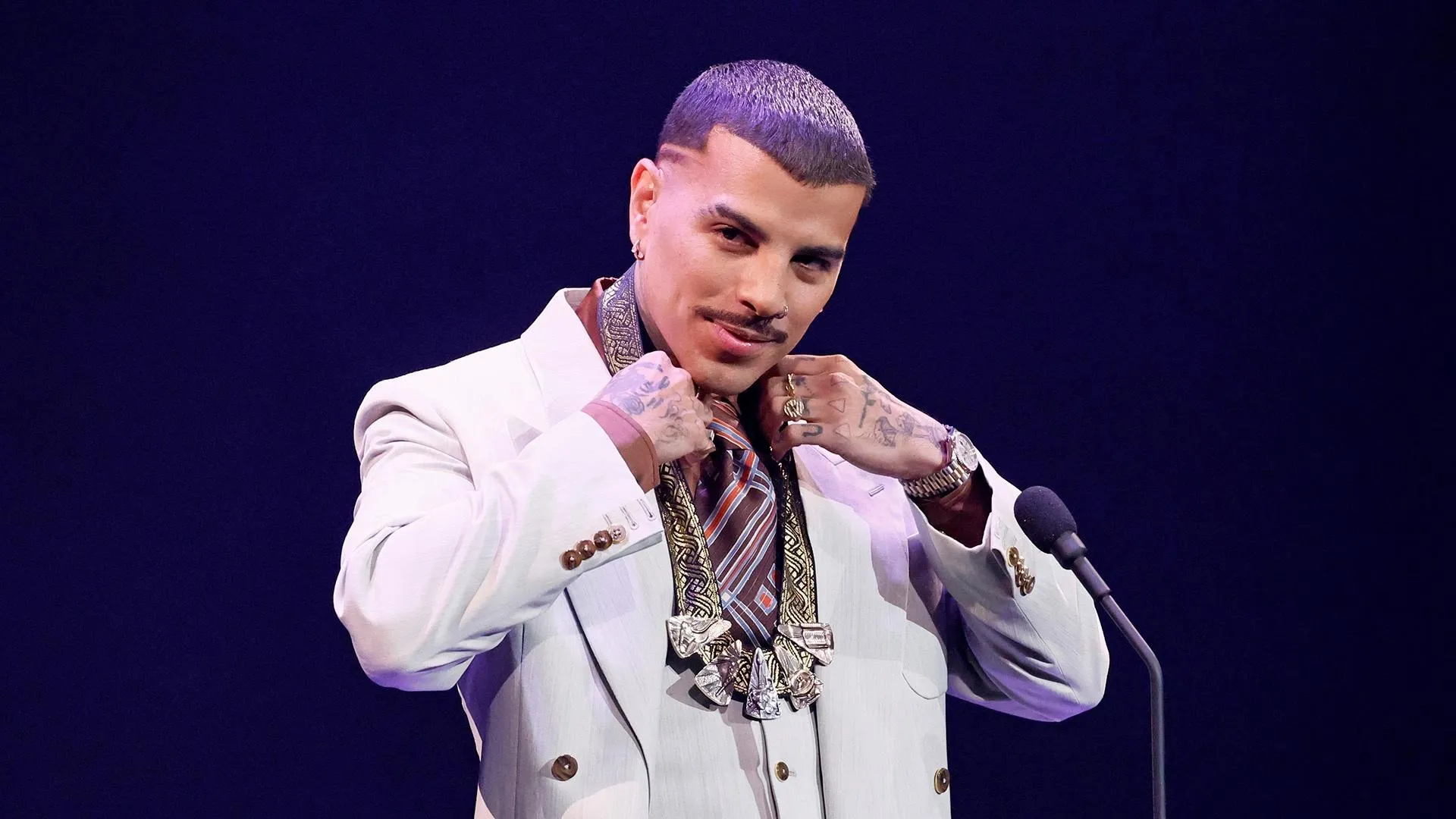

According to appraiser Thomas Lecky, this gorget was originally owned by two of the senior-most chiefs of the Sioux Nation in the 1870s, Red Cloud and Spotted Tail.

Sep 2, 2025

Originally published on: Apr 7, 2014

- Editor's Note: This article discusses the complex topic of Indigenous cultural objects, drawing on expertise from several of ANTIQUES ROADSHOW’s Tribal Arts appraisers. The article is not a comprehensive treatment of the topic, however, and does not constitute legal advice. It is for informational purposes only and may not reflect the most current legal developments. If you think you may need further guidance about items in your possession, you should consider consulting an attorney.

DURING ANTIQUES ROADSHOW’s 2005 visit to Tampa, Florida, a guest named Charlie brought several items belonging to his great-great-uncle, W.S. Starring. After joining the U.S. Army in the late 1860s, Starring was stationed at Fort Laramie along the Oregon Trail, and while there, he studied with the Sioux people living in the area.

In December of 1866, Starring, along with J.K. Hyer and Sioux interpreter Charles Guerreu, published Lahcotah, a book that was part dictionary of the Sioux language and part pronunciation guide. Along with the book, Charlie also brought to ROADSHOW two gorgets, decorative pieces that would have been worn around the neck on a breastplate.

Tribal Arts appraiser Thomas Lecky explained that Charlie’s gorgets “happened to be owned by two of the senior-most chiefs of the Sioux Nation in the 1870s, Red Cloud and Spotted Tail.” But these two gorgets, like many other Native American objects — such as the Anasazi Ceramic Vessels appraised by Anthony Slayter-Ralph in Kansas City in 2013 — raise important questions often asked by owners and collectors of Native American objects: What should be done with prehistoric and other Native objects that you may already possess, and when is it okay to buy or sell them?

Many Native tribal objects raise important legal and ethical questions: Are they appropriate to own, or buy, or sell? Multiple laws make a complicated field

Many Laws Make a Complicated Field

While Native artifacts continue to be highly sought-after collectibles on today's market, it is "a dangerous field to collect in," according to ANTIQUES ROADSHOW Tribal Arts appraiser Bruce Shackelford, who is also a consultant for museums regarding Native American history and objects. "It's not unusual for us to see things on the ROADSHOW that are questionable," he says.

"It's a very complicated issue," adds John Buxton, another appraiser who has assessed many Native American objects on ANTIQUES ROADSHOW over the years. "There are issues around where objects come from — Are they from public lands or private lands? Are they grave goods? Were they made from an endangered species? Do you have good title? Are they stolen? It's a lot more complicated than it was 25 or 30 years ago."

Numerous laws relate to the subject, and most affect the buying and selling of prehistoric pieces. Many laws forbid the taking of Native American artifacts from Native and federal land, including national forests, parks and Bureau of Land Management land, unless granted a permit to do so. And to add another layer of complexity, states, counties, and cities have also passed their own laws restricting the taking of Native American objects.

In addition, the Endangered Species Act forbids the sale of any Native object — old or new — that uses animal parts from endangered or protected species, such as eagles and other migratory birds.

A Pre-Columbian Anasazi ceramic vessel, appraised by Anthony Slayter-Ralph in Kansas City, August 2013.

Why So Many Laws?

The animal protection laws are intended to curtail the killing of animals for making into salable Native American objects. Shackelford notes that other laws are designed to respect the graves and cultural belongings of Native American groups — sometimes calling for the return of prehistoric and other objects to ancestral peoples — and to protect archeological sites and gravesites from ransacking.

"There's a scientific way to excavate a site," Shackelford says. "It involves documenting the site and preserving information. If someone goes there and contaminates that site" — which is inevitable when objects are illegally excavated — "it's done."

"To a good archeologist it's not about the stuff," Shackelford continues, "it's about the knowledge that can be gained from the site. But to the unscrupulous dealer, it's just widgets and pots. They want things that can be sold in isolation. ... We have an obligation to preserve history for future generations, and not just have things for our living rooms."

American Indian stone tools, from the pre-Columbian Woodland culture, appraised by Slayter-Ralph in Detroit, June 2013.

NAGPRA: The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

According to Buxton and Shackelford, the law that has perhaps most influenced the market in prehistoric and other important tribal objects is the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, known as NAGPRA. The 1990 law provides a process for federally funded museums and other federal agencies to "repatriate," or return, certain Native American cultural items — which may include human remains, objects from burial sites, or other sacred objects or important cultural objects, collectively called "cultural patrimony" — to the Native American tribal groups they came from.

According to Dr. Sherry Hutt, who served as the national program manager of NAGPRA from 2004 to 2014, it's often hard for people to know what they have, and what you are permitted to do with the Native American object.

"So many times we get calls in which people say, 'This was in grandma's attic, and we want to do the right thing,'" Hutt said, noting that most people can't be expected to "know what comes from a grave." She emphasized that in the cases of individuals, the National Park Service, which oversees NAGPRA, seeks to avoid "finger-pointing."

Furthermore, in July 2021 the U.S. Interior Department began consulting with tribal and Native Hawaiian community leaders to conduct a systematic review of existing NAGPRA regulations, in view of eventually proposing updates to the legislation, which Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland called "long overdue."

On January 12, 2024, the NAGPRA act was updated to make significant changes in favor of Native American tribes and the authority they have over the repatriation process. For example, NAGPRA updated its definition of an "object of cultural patrimony" — defining it as having an ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the Native American group or culture itself, rather than as property owned by an individual member of a tribe.

Commenting on the outcomes of the most recent changes to NAGPRA, Buxton explained that one of the most important concepts is the "inalienability" of a cultural item from the group it originated from. Which is to say, if a tribe asserts that a certain artifact or object from the tribe is an example of cultural patrimony, then that implies it was never truly subject to individual ownership in the first place, and thus could not have been legitimately sold or traded away by an individual member of the tribe.

Second, knowledge of who can authenticate cultural objects now falls solely to the Native American tribes — rather to than a museum or federal agency — as a tribe’s elders are presumed to be the figures who possess the traditional knowledge, oral histories, and cultural understanding necessary to categorize any particular item as a sacred piece.

Third, in cases of disagreement, museums and federal agencies are now responsible for demonstrating that an object is not cultural patrimony if a tribe asserts that it is, rather than the tribe needing to prove its ownership.

According to Buxton, the revised NAGPRA framework essentially aims to correct historical imbalances and empower Native American communities to reclaim their cultural heritage by recognizing their inherent authority in defining and protecting what is central to their identity and traditions. Institutions that were formerly considered primary arbiters of cultural significance and ownership must now defer to the self-determination and traditional knowledge of Native American tribes when it comes to sacred objects and cultural patrimony.

Go Back to the Source

So what's the best way for someone to find out what they can do with what they already own? On that question, there is still significant debate.

Sherry Hutt, the former NAGPRA national program manager, recommended that owners who want to learn the provenance of a Native American object take a simple step. "If you don't know what you have, it's okay," she says, adding that people should "ask the tribe. That's the best advice — particularly if it looks old or special, because of the beading, the imagery, or the feathers." Tribal representatives will tell you an object's significance, Hutt says — or its insignificance.

"You may just have an old pot," Hutt continues, "in which case you can decide to keep it, sell it, or donate it to a museum."

Buxton agrees that investigating the provenance of your Native American object is crucial because "sooner or later someone is going to pass it down, sell it or donate it."

"I'd take it to a museum, or an auction house, or a qualified appraiser," Buxton said in 2014. However, as of the updates brought about in 2024 under the NAGPRA act, going to a museum may not be enough.

Buxton now advises people against using museums as the one and only source for learning more about their objects, even though he says museums can still be useful. While museums remain valuable in terms of learning the provenance of an object and providing historical context, they are no longer the final authority and cannot override a tribe’s own position on an object.

“Museums may facilitate contact with tribal representatives or provide documentation to assist consultation," Buxton says. "If provenance is murky, museums can still help reconstruct acquisitions chains, which tribes can review.”

Sean Mooney, managing director of The Rock Foundation, a private foundation that houses a large collection of Native American and Indigenous cultural materials, agrees that museums are important, yet the processes for how museums and Native communities interact have evolved into a complex landscape.

“One complaint I have heard over and over again is from the point of view of Native advisors and cultural leaders … which usually centers on the question of who (within the community) has authority to make decisions on cultural matters.”

For example, he recently told ROADSHOW by email, tribal leaders who may be considered the foremost scholars of their own cultural history may not be recognized authorities under NAGPRA. “Often, those people on the [NAGPRA] published list are not as well informed as the scholars are, and this is further complicated by age, status, and rank. So, in these cases, there are hard feelings raised by the process itself, which is something nobody in the U.S. government would be able to anticipate as an inadvertent complication.”

Furthermore, as Bruce Shackelford told ROADSHOW recently, “There are tribal groups in the U.S. that did not sign on to the NAGPRA agreement and are not recognized under the guidelines. But they are legitimate organizations for charitable contributions and some are recognized as tribal entities by the states they reside in.”

Still, Mooney says, the conversations that the new NAGPRA updates open up are vital. He says he’s encouraged by the growing number of Indigenous professionals in museums who understand both sides of the issue. They help to redefine museums not as extractors but as safe spaces for cultural learning and stewardship.

While there are small yet significant steps being taken to improve how an item is repatriated to a Native group or classified as cultural patrimony, our experts agree that the current landscape for doing so is still a complex and evolving one. Those looking to learn more about their own object should bear in mind that how the process unfolds will be on a case-by-case basis. For more information, owners can visit the Bureau of Indian Affairs NAGPRA program website, or contact an expert in the field.

If you don't know what Native group your object came from, Hutt also suggests you contact a museum, such as a state museum, which may often have repositories of Native American materials; or a museum that exhibits these objects, such as the Heard Museum in Phoenix, the History Colorado Museum in Denver, or the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. They will usually be able to identify which Native American group made the object, and may also be able to determine whether it falls under NAGPRA's legal umbrella or not.

Take Precautions: Buyer Beware

Shackelford says that enforcement of laws pertaining to prehistoric objects has been stepped up in recent years because the potential to make money from archaeological treasures has expanded, especially from pieces taken from graves, which "tend to survive in a more complete state" than those found in excavation sites, Shackelford says.

"Pieces that once sold for $50 now sell for thousands, or tens of thousands of dollars," Shackelford says. "There's a large market for Native artifacts in the decorator crowd. A lot of people who grew up with little Anasazi bowls on the coffee table now want bigger bowls to fill up large Southwest-style houses."

"Make sure to get paperwork by a reputable seller so you have something to stand on if it blows up in your face," Shackelford says. "If the guy says it's not a problem to buy it, have him put it in writing. If there is a problem, you can take him to court and say you want your money back."

Shackelford also notes that there are abundant Native American materials on the market that are both beautiful and legal and ethical to purchase, such as decorative items made by contemporary Native American artists and craftsmen.

And what of that Anasazi pot that showed up in Kansas City? "It was probably found on private land, so it's probably okay to sell," Shackelford says, repeating a word that comes up often with objects that haven't been vetted thoroughly. "Probably."

Additional Resources

- NAGPRA: Facilitating Respectful Return

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Servce: Can I Sell It?

- Interior Department Announces Final Rule for Implementation of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

- July 2021: Interior Department Announces Tribal and Native Hawaiian Consultations to Discuss Updates to NAGPRA

Gallery of Indigenous Artifacts

Zuni olla pot, ca. 1885, appraised by John Buxton in Milwaukee, July 2006.

Dennis Gaffney is a freelance writer in Albany, New York. He has been a contributor to Antiques Roadshow Online since 1998.

Luke Crafton is ANTIQUES ROADSHOW's director of digital content and managing editor of the series website. Luke has been a producer with ROADSHOW since 2006.

Melanie Albanesi is a former digital producer for ANTIQUES ROADSHOW and frequent content contributor to the series website. Melanie was a producer with the series from 2019 to 2026.