Understanding the Origin of American Indian Boarding Schools

By the late 1800s, forced assimilation — in the form of compulsory boarding schools — had become another tool the U.S. government used to address what mainstream America considered the “Indian problem.”

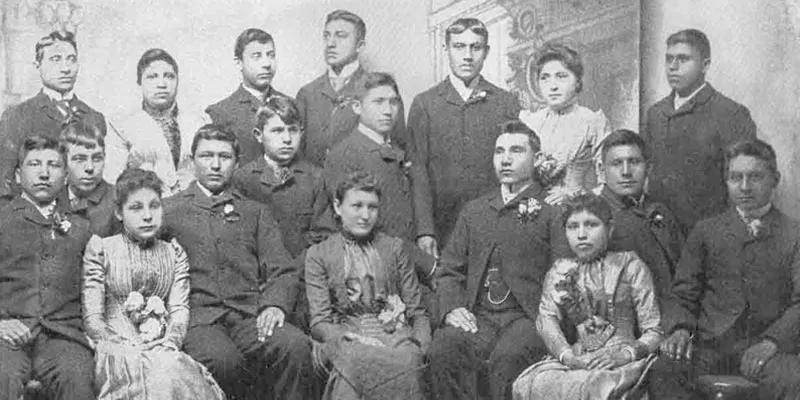

Portrait, ca. 1890s, from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, titled "Educating the Indian Race. Graduating Class of Carlisle, PA." (Photo source: Wikimedia Commons)

Aug 14, 2024

Originally published on: Apr 13, 2020

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE:

- Army officer Richard Henry Pratt founded the first federally run Indian boarding school in 1879, adopting the cruel philosophy "kill the Indian, save the man."

- The assimilation system separated hundreds of thousands of children from their families, forbidding their tribal languages and traditions while forcing the adoption of American customs.

In years preceding the era of Indian boarding schools, under the doctrine of “Manifest Destiny,” the U.S. government was continually engaged in removing Native American tribes to take over their land, pushing them further and further west, and in battling those tribes that were resistant to being removed.

By the late 1800s, assimilation became another tool the U.S. government used to address what mainstream America called the “Indian problem.” One tactic of the program of assimilation was making Indigenous children attend boarding schools that forced them to abandon their customs and traditions, with the goal of having them adopt mainstream America’s beliefs and value systems.

The first federally run Indian boarding school was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, in operation from 1879 to 1918. Army officer Richard Henry Pratt founded the school, which became the template for instituting a system of forced “Americanization,” using strict militaristic discipline to sever Native American children from their Indigenous heritage. It was Pratt who coined the phrase “kill the Indian, save the man” — a philosophy that permeated Indian schools for generations.

This system of assimilation meant that children were separated from their families and communities for long periods of time. The government funded or oversaw more than four hundred Indian boarding schools, both on and off reservations. (Taking after the federally run Indian boarding schools, Christian Missionaries ran over one hundred schools.) Hundreds of thousands of children were either forced to attend these schools or went because there was no other school available to them.

Related Article: How American Indian Reservations Came to Be

The schools prohibited the children from speaking their tribal languages, required them to wear American-style dress and hairstyles, and made them give up their Native American religions for Christianity. In addition to standard academic lessons in subjects like reading, writing and math, students learned trades that were marketable in American society, such as carpentry for boys and housekeeping for girls.

By the 1920s, support for the Indian boarding schools’ strict assimilationist methods was declining. The 1928 Merriam Report recommended discontinuing European-American-centric cultural courses in schools, and the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 promoted actions that would give tribes more opportunity for self-determination and self-governance.

The book, titled A Courier in New Mexico, which Martin Gammon appraised at the ANTIQUES ROADSHOW event at Desert Botanical Gardens in Phoenix in April of last year, was made by two teachers and their Native American elementary school students at Tesuque Pueblo school in 1936. The rare book is an artifact of this transitional period.

Several miles away from the one-room schoolhouse was the Santa Fe Indian School. Established in 1890, the Santa Fe Indian School had followed the Carlisle model, but was changing with the times by the 1920s, when it started to focus on traditional arts. In fact, art instructor Dorothy Dunn ran a studio school on the Santa Fe Indian School campus in the 1930s. Dunn was a proponent of her students using Native American subjects in their art, in a narrative style that she believed yielded authentic representations of Indigenous cultures. (Although Dunn’s definition of what was authentic Native American art was criticized in later years, she is credited as having helped improve education for Indigenous students, and for helping to develop a new Native American painting style.)

In the following decades, Pueblo leaders fought to gain control of the Santa Fe Indian School. Today, the school is tribally managed.

As of 2023, there were four federally-run, off-reservation boarding schools still operating.

Related

Unspoken: America's Native American Boarding Schools (PBS Utah)

Sarah K. Elliott is a producer for ANTIQUES ROADSHOW and a frequent content contributor to the series website. Sarah has been a producer with the series since 2000.