Interviewer: Hi. What attracted Calder to Paris? Why did he first go?

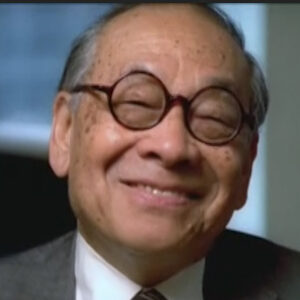

Alexander Rower I think I think because both of his parents were artists and they had been in Paris. It’s been a lot of time in Paris. And everyone was going there. It was the place to go. New York wasn’t really exciting. It was kind of state and. What artists were doing in the orrock wasn’t exciting to him. And he, uh, he went he just got on a boat and went, oh,.

Interviewer: Why do he keep going back?

Alexander Rower Well, he went. He went back and forth because he ran out of money. I mean, he made some money. He went over. He had a great time. He really expanded his his horizons. He made a lot of work there. And then he would run out of money again. He kept trying to get jobs, doing illustration and almost any kind of thing related to art in Paris. He illustrated things for Paris newspapers and things like that. But he would run out of money and he’d come home and then he’d make some more money here. He’d have a show and sell a few things and then go back.

Interviewer: Give us an answer. Yes. What was he not getting in America that drove him to Paris?

Alexander Rower It’s I think you could say that he he was looking for a certain kind of freedom and he thought that he might be able to find that in Europe. And Paris was the center of Europe artistically. There were so many artists there, there that were doing work. It was exciting and different and it was very different from the American scene. So.

Interviewer: Can you give a sense of what was being created here and what was being created there? Who the people were? Who did he become friendly with? Let’s say. Twenty six in the 20s, 30s.

Alexander Rower Well, when he first went over.

Interviewer: You can also use his name occasionally.

Alexander Rower When Calder first went to Paris in twenty six he bumped into people that he had known at the Art Students League. And people, you know, so many New Yorkers where there are so many Americans were there that he would sit in a cafe and and meet people that were American. You know, it’s very, very cheap for Americans to be there. And so he he met all kinds of people through acquaintances from New York. Some of the first people he met there really helped him sort of get established not as an artist, but establish it’s just living there and be more comfortable with being in a new place. And and that kind of thing. Pesca is this was this wonderful guy who was a friend of his father’s, had known his father in New York, knew his father’s work and so forth. And Pesca wrote an introduction to an early catalogue and sort of helped him along, introduced him to people. There were lots of different artists in his in his area that he hung out with and discussed ideas with. And this wood sculptor, Jose Di Craft told him where to go buy chisels and hammers to carve an. You know, that kind of thing.

Interviewer: What was the movement of art at the time? And did he embrace it? Was he did he fit right in?

Alexander Rower You know, he never Calder, never really was a joiner. I mean, he joined a few organizations in his life. But he he he worked along his own path. And that’s one of the really interesting things about him, is that he just sort of chose his direction and went with it. And it really didn’t have a lot of association with movements or other things going on. I mean, he certainly was inspired by his time and by people he knew and seeing exhibitions and so forth, but his wire sculpture was something he developed out of just his childhood and making bits of things. As a kid, it was the sort of logical extension of making toys and making sort of, you know, little projects. But also the freedom that he experienced in Paris was allowed him to make these these very exotic wire sculptures. No one is making wire sculptures.

Interviewer: Was it difficult over there for him? Was it easy? Did artists of the time to say, hey, you’re a new artist, come on, let’s have a great time? Was he accepted? Did he care? Was he a loner? What kind of person? What was the time like?

Alexander Rower He was, Calder was very social. He loved to go dancing. He wasn’t so social around art. He didn’t enjoy discussing art, per say. But he liked to hang out with artists and be part of a community. You know, go to be part of the Paris party scene of that time within the art community. But. What was your question?

Interviewer: Was he accepted by artist of the day?

Alexander Rower Well, back then, there were you know, the personalities weren’t quite as extreme as you find today. You know. I would say, yeah, he was accepted, but there was nothing. Yeah.

Interviewer: Who were his strong influences in his early years?

Alexander Rower Well. Calder’s work begins with sculpture that’s more typical of the time. If you look at the work that he’s doing in 1923, I mean, his first paintings and and the drawings he’s doing, they’re related to to the teachers. He’s studying under there are students league and so forth. There’s this there’s this tremendous change that happens. I mean, he sort of becomes more mature as an artist. He’s a great draftsman as he studied as an engineer. You know, he has a great sense of line and spatial relationship and all of that, which comes in later with his abstract work. But the wood sculpture. Well, some of it is is really fantastic and great carvings. You can see that they’re very related to what’s happening in America at that moment. And. So the transfer from being in New York to being in Paris sort of opens him up to being able to experiment in a way that he really didn’t before.

Interviewer: Is he conscious? Then he ask a different way. Does he know? Is there a moment when he sort of breaks out and finds a style that is uniquely his own? t’s no longer like, what’s it like? Was it a slow process finding his art?

Alexander Rower When he arrived in Paris, he was unsure what he was going to be doing because he had so many different possibilities in the same time he had to make money. The. When he started.

Interviewer: Rolling. Take two. Was there a moment when he found his style?

Alexander Rower Well, when he was in Paris in the 20s, when his arrival in Paris really expanded all the possibilities for him and he didn’t know exactly what he was going to do at that time, he was doing illustration. He was doing whatever projects came along. You know, he illustrated a brush law for this steamship line and made some posters, you know, various different jobs, whatever he could get, basically. And he was he was truly, for the first time, so much on his own. You know, so much under his own steam. I think it really allowed him to experiment. Allowed him the freedom to try and do new things and and to work from things he had done in New York. He had already made woodcarving. He had already made wire sculpture in New York. But when he arrives in Paris, somehow it’s so fresh, it’s such a exciting new place that he he he really begins to to evolve into that. So I think you could say that his his arrival there made a huge impact on him.

Interviewer: Talk about whether. This is camera roll. Early years again. He was Harris. Can you talk about how much money he had. Was he rich or was he poor. Did that affect his choice of materials?

Alexander Rower Well, when Calder decided to go to Paris, his mother helped him and gave him a little money and sent him money when he was in Paris for the first time. Just to help him get established and be more comfortable. But basically, whatever money he had is money he made. From his from selling work here and there, from doing illustration and so on, his. His sense of materials, though. I don’t believe comes from lack of funds. I think it comes from a real honest sense of metal. You know, iron, steel. He loved it. I mean, he studied engineering because he loved machines and he loved mechanics. His sense of the different qualities of wire, iron and steel, that that the hardness of the different kinds of them, the spring tension and so forth. He loved all that kind of stuff and he liked to use the right material in his work. If he made something out of really thin wire, he’d use a wire that had integrity so it couldn’t get damage. You know, as opposed to, you know, some somebody might use an aluminum wire that was thin. Well, if you just touch it, it bends. It’s very malleable. And he wanted just things to last. When a Mobil drops off the ceiling, you know, the string breaks or something like that. It’s a little paint chips off, but it doesn’t damage the work unless it’s really, really had a catastrophe.

Interviewer: But in those early years, he was using wood, the scraps of wood that he was carving, glass shells he was using.

Alexander Rower No, no, no. He wasn’t using glass or shells at all. He was using wood and his wood. The first wood sculpture that he did was made from a fence post. It’s made out of oak. And it’s a beautiful piece of wood. But it’s not just a scrap of wood. It’s a chosen piece of wood. It’s not just something that was kicking around when. He found this wood and he he carved this cat out of this piece of wood. And the other sculptures he made were from real hunks of wood, really nice wood, ebony, Coca-bola, you know, really nice Woods, fine words. So is he wasn’t he wasn’t. A lot of people have the idea that Calder was a junk man, that he’d go to the junkyard and find his materials and make these wonderful things, which in fact is not true at all. I mean, on a few rare occasions, he would find something that was discarded and use that in his work. But that wasn’t his modus operandi. I mean, he bought his materials from a supplier and use those materials. And he’s very particular about his materials. It wasn’t just anything that came along during the war. It is a whole different story when his his aluminum sheet, which was strategic metal for making airplanes to bomb the Nazis. He he decided to really try and find other materials to use. And that’s the moment that he used broken bits of glass, made mobiles from bits of glass and string. And he decided to go back to bronze. He he he had two periods of bronze, one in 1930 in Paris, where he made these little acrobatic figures in animals. And then in 1944, still during the war, he made works out of plaster. And he intended the plaster’s to actually be sculpture. And then he started casting from them in bronze, even in aluminum. He was sort of dissatisfied with that. It’s still it’s still too heavy. He called them mud, which it had been the material of his father and his grandfather making things in plaster, casting in bronze. And he didn’t really like it. But since the war was on and since it was what was available to him, it was inexpensive. He tried it again.

Interviewer: Did you he pressure inside or from the family. He was from a long line of sculptors.Alexander Calder, Calder, Masons.

Alexander Rower Well, we don’t really know how many stone carvers and people involved as artisans. There were prior to Alexander Calder. We know there were some before Alexander Milne Calder came to America. He came from a line of some. But basically just say that before he came.

Interviewer: Can you say that again?

Alexander Rower Well, when Alexander Milne Calder came to America, he had a lineage of artisans behind him. And he arrived in Philadelphia, discovered there were no municipal sculptors and said, what the hell, I’m going to be a sculptor. And he made some wonderful sculptures are very classical. The William Penn that’s on top of the city hall buildings. Thirty eight foot tall bronze sculpture. It really is his finest achievement. And it’s quite a wonderful thing. But it’s it’s classical. There’s nothing his personality isn’t so obvious in the work. And his son, Alexander Stirling Calder, made much more emotional work. Still there figures. But they’re swans. The Logan Circle fountain in Philadelphia is wonderful. It’s full of mermaids. And, you know, but then when Calder comes along, he sort of. He’s not interested in that. He’s not interested in the past. He’s not interested in modelling, although he does some of it upon occasion. But he’s really interested in constructing things and his parents are very accepting. Although you can’t say they understand what it is that he’s doing. They’re very accepting and supportive. His mother is a painter and some wonderful portraits of him as a child that she did. I think eventually they really enjoyed his work. But it took a while for them to begin to understand what this this new stuff was.

Interviewer: But he didn’t like the representation or he didn’t like statues of soldiers. Bob Osborn talks about not wanting to get car traveling in Europe. Guy on a horse.

Alexander Rower Yeah. Yeah, he he he he really didn’t have much use for municipal sculpture in that sense, in the sense that. You know, we have to honor someone and make a sculpture of them and place it in a park. That wasn’t what he was about. He was very interested in forces and energy and power and strength, as you can see in the later stables. You know, seeing one of those in a park, in a public setting, you got to storm King and see these wonderful things. You really get a sense of what moved him, what his motivation was. Those those kind of works. You can see the beginning of them in 1937 where he makes his first kind of outdoor stabile called the whale. And so it’s it’s it’s terrific. It’s so exciting that he he has this vision of making large work for public spaces. At the time that he made the whale in 1937, he made a whole series of little maquettes, little models which were intended to be enlarged. And for the next three or four years, he made all these little models hoping that that someone would come along and say, great, I want one for my garden. And no one did at that time. And he he he came back to it later when he had his own, when he had made a little money and kids could afford to make them for himself, made them make them on his own account. He made started really making them. And at that time, international architecture was becoming all the rage and everybody needed a sculpture for that side of their new building.

Interviewer: He was interested in the cosmos of the universe. It was a time when telescopes were being perfected and new planets were being discovered. Can you talk about what he what his excitement was, how he brought into his work? 30s.

Alexander Rower I think this whole relationship to the universe is a little bit overblown. I think that his. I don’t believe that his earliest abstract sculptures that he was making in 1930 and 31 were related to. Kind of this this this specific sense of our cosmic heavens. I think those were I mean. I mean, sure, there’s there’s a relationship there. But I think that too much has been made of that. I really think that we need to look at these things as as sculptures and maybe look at them more in terms of natural forces than the universe specifically. I mean, the.

Interviewer: His mobile’s certainly looked like the cosmos to me. But you say it’s not the cosmos. It’s more natural forces. Can you explain?

Alexander Rower No, I. The problem with trying to understand Calder’s sculpture and his artwork, but by defining it as the universe is this is a tremendous minimizing of what his work is. Everybody needs to have some sort of avenue to begin to understand an artist’s work. And the universe has been one thing that’s very consistent in the description of what Calder’s work is about. But if you really begin to study his work, you’ll see a lot more than the universe. That’s the point I’m trying to make, is it’s it’s it’s too easy to say this mobile is a cosmic model. And this mobile represents the leaves on a tree. And this mobile is the wind through the mist. You know, I mean, it helps people understand and have begin to get to a point where they have a real response to art to do that kind of thing. And and it’s necessary. But I’m I find it a bit much sometimes.

Interviewer: I want to continue on this track though we jumped ahead. My question is where consistency your style. What is a deeper explanation of his work? If saying the cosmos is superficial is. What is his work about?

Alexander Rower One of the great things about Calder’s work is his allowance for the audience. And when he was making his first abstract sculptures in 1931, specifically the beginning of 31, he came upon this idea, which was who is he to determine the final composition of his sculpture and who is he is the artist. You know, shouldn’t it be some allowance for the viewer, the public, the owner to participate in that composition? And he made these sculptures that are articulated. They have moving parts. So there’s an arm with an element and and a hinge kind of thing. And you can move it and sort of position it in different ways. This was a great innovation. This was a tremendous idea. There were artists before him. Arp made these wonderful reliefs and constructions which had the idea of the randomness of throwing things on a board and allowing that to be the composition. And it’s related to that I think. I think that the interpretation of his work has to be through the process of the individual, examining the work and exploring the work and communicating with the work to get to the point of having a rapport. And with all artists, you need to have these little phrases and ideas that direct you in a certain way. And I’ve gotten tired of those directions. And I, I, I like to think about having a fuller approach to this work.

Interviewer: Now, did you say to the audience? What was the phrase you used in 1931. This early sculpture? What did he do then if he wasn’t. You were sort of talking about and I didnt hear the end to that. You said his early sculptures. He didn’t want to tell the audience what to think or feel. Or was he not naming the pieces or how was that manifested?

Alexander Rower Well, he didn’t want to dictate the interpretation. I mean. He wanted to make an allowance for different possible. I don’t even want to use the word interpretation. It’s more a response, communication with his works and a simple response like joy, you know, doesn’t. You don’t need an interpretation to look at it one of his sculptures to experience joy. But at the same time, there are a lot of other interpretations, a lot of other experiences that you can have with his work. Some are extremely somber. Even even ones that are emotion and light and airy have this tremendous feeling of this overbearing quality, you know. There’s so many different ways and. So back to what I was saying before is he wanted to let the audience participate with his work. He didn’t want to make a painting like like like the surrealists with this icon here, here and here, has a specific meaning, has a specific interpretation. Isn’t it bizarre and exciting and that kind of thing? He was really an abstract artist and his work was in the abstract. You know, if you look at a painting by de Kooning that was painted in the 50s, you see these incredible driving force in his work and you don’t need to interpret it as some sort of thunderstorm. You know, you just it hits you. And it’s the same with Calder’s work. You look at it and you don’t need to interpret it as this is some sort of model of the universe. I mean, he was inspired by the universe, without a doubt. But I think more in the sense that the heavenly bodies were these great forces and they had vectors and they had amplitudes and they had mass and force and all the things that interested him. And that’s more what it’s about. It’s more about the cosmic forces than the cosmic bodies. You know, than the travelling, the orbit of planets. Sure, there’s a relationship there, but it’s much more about the power of those planets. It’s much more about how the planets, the force of them.

Interviewer: That was it. We got all the way around and you answered it perfectly. In all I’ve read his autobiography, Lippmann’s book. There’s not a lot written about him. But in all I’ve read, there seems to be little struggle of an artist with his art. Can you talk about whether there was or wasn’t? What how he pushed himself or did it just come easily?

Alexander Rower I think that his process of making art was a very natural one. It wasn’t forced. It wasn’t. He had such integrity as a person and there was nothing put on about him when later in his life when he had money, he didn’t know he wasn’t into buying fancy clothes and driving fancy cars. He he lived the same basic lifestyle that he did forever. I mean, he built himself a new house and a new studio and and, you know, life progressed. But he wore the same LLBean Red Shirts, you know, and the same chinos and the same tired all work shoes. And he rarely dressed up. And he wasn’t affected by all of this. It was. So he lives so naturally. What was your question?

Interviewer: Did you have a need to create? Did he get up in the morning? You know, was exercising demons? Where did it come from or did it just. This is fun and this is what I’m going to do today.

Alexander Rower No Calder had a definite need to create. He had a driving force. He worked every day and in the process of making the catalog risen. We’ve identified 16000 works, which includes all works of all media from the smallest little sketch to monumental sculpture. But that means he was making a work a day for 50 years, you know, makes a little sketch one day on a huge sculpture the next day. I mean, you know, sort of this absurd idea. But he was always making something and he always had little bits of things in his pockets. He always had a pair of pliers. You know, he put on a jacket to go to an opening. He had a pair pliers in his pocket. You know, he was always himself. He was always available to to work in the moment. So I would say certainly he his work gave gave meaning to his life. And it was just a drill.

Interviewer: Cut. Do you remember him pulling something out of his pocket and making something for you? Making something. Do you have a memory of that?

Alexander Rower I remember once as a child, my grandfather making me a little donkey and cart. This was in Connecticut. We were just together one morning and he called me over. Didn’t know what he wanted. You know, he’s calling me over and he said, I’m going to make something for you. And he started making this little thing just with a spool of wire and a pair of pliers. And first he made the cart and I didn’t really know where it was going, what it was becoming. And then all of a sudden, this whole donkey had been constructed. And then it was this donkey cart. And I don’t know what inspired him to do that at that moment. I guess he thought I needed something to play with. I never really considered you know, I was probably. I was probably six or seven years old, and I never considered a toy. To me, it was extremely.

Interviewer: So you didn’t play with it?

Alexander Rower No, I never I never considered it a toy. To me, it was a very precious, wonderful. I mean, it was a sculpture. Even as a child, I recognized that it was something to preserve, something to keep on my shelf, as I always did.

Interviewer: Did he play with those things. Was he as distancef, if you will from his work is putting it on a shelf.

Alexander Rower Well, in 1926 and called arrived in Paris, he began making the circus and the circus is something that’s, I think really been misinterpreted. It was I mean, if you go to the Whitney Museum and you look at the circus, you’ll see something that looks like a little puppet show and it’s a series of dolls. And you don’t really realize that. In fact, what it is, is performance art. You know, here are these things that need a human to activate them. But it’s more than just a puppet show. It’s something the artist is more than half of the show. His interpretation of the circus through this assemblage of of acts and figures is really what it’s all about. So to not have him be part of the circus. For me, the circus doesn’t exist. The circus is gone. You have these. It’s like Christo. Christo wrapped something. And you can buy something that’s related to the wrapping. But it’s not the wrapping. The wrapping doesn’t exist anymore. It was that moment. And the circus doesn’t exist anymore either. The circus is something that has bits of things left over and they’re wonderful bits of things. Nonetheless, unfortunately, the two circus films that were made in 53 and sixty one are much too late to understand what the circus was in nineteen twenty eight at the height of the circus 1929. And in Paris at that time, the formal circus, the real circus was something you go out in the evening, you dress up and go out and see the circus. It was an adult show and they had circus critics like we have theatre critics today. They took it very seriously. And so Calder’s circus was reviewed by circus critics. People came and took it very seriously that they really treated it as a serious event, not just a puppet show.

Interviewer: Why was it? I’m glad you said that because I’ve always looked at it and said this is very nice but I dont get why this was a hot night out in Paris with Niguci and Miro and this whole night scene. Why was it such a great scene? Do you have a sense?

Alexander Rower I think the circus was something it was something different. It was a hybrid. And to have this kind of hybrid be presented. I think was sort of shocking, and I think people really responded to that. You know, it wasn’t the circus. It wasn’t. I mean, the formal circus. And it wasn’t a puppet show. And it wasn’t all of these other possibilities. It was this event. And people responded to it in the way that you respond to a new art movement. You respond to something exciting, something you want to see, something you might want to participate with in some fashion, you know. And the way that he distilled the viewpoint of the actual circus and interpreted that in his circus was something people really responded to, especially the circus critics. They saw that he he had this amazing relationship going on. You know, if you look at his sketches, his animal drawings done in 1925, which he published in a book, Animal Sketching, you’ll see all kinds of potential energy in those drawings. You’ll see these animals. It could be a lion asleep. But you see the muscles. You see the power of that animal. And you can see the same thing in the circus. The interpretation there from the original, you see the strength of the guy who’s lifting the weights. I mean, you know, it’s this engineered figure that lifts this this bar. But at the same time, you can understand the power. It’s not just a simple action like this. It’s got strength and it has motion in it. It’s really this wonderful caricature, but it’s more than a caricature.

Interviewer: You talked about him always having a pliers, having bits in his pocket. He was making things for the house. He was doing utensils. Can you talk about that? And what prompted hi. Did he do iit just for fun or utilitarian use or. Tell us about that.

Alexander Rower Well Calder made household objects for all kinds of reasons. I mean, during the war, he had materials and he he he made things for Louisa to use in the kitchen. And I think I think I think that a lot of reasons. I think one so you don’t have to buy these things. But two he he he drives such great pleasure from making them and making them just the way he wanted to use them or just the way that Louisa wanted to use them from a garlic crusher, you know, a beautiful car, piece of wood to smash the garlic in the bottom of the bowl to to so many things in the kitchen. You know, all different kinds of things that were made for a particular moment, a particular party which were only used once, which now just are there and are these wonderful objects.

Interviewer: And he had a sense of humor about those objects too?

Alexander Rower No. I wouldn’t say so.

Interviewer: I don’t want to talk about the toilet paper roll. But obviously, the guy wasn’t just saying this is purely utilitarian. You ook at it and there’s a joy in that.

Alexander Rower I wouldn’t interpret these things in that way at all. The works that he made the household are not some kind of joyous humorful things. I mean, a few of them have something funny going on, but they were they were made as beautiful objects to be used. That’s what they were.

Interviewer: Lincoln Christine has a wonderful description in this book called Their Show at the Harvard Society of Contemporary Art in 1930. He gets off a train. He’s got a suitcase. He doesn’t have a dozen or so pieces that were promised for the show, which opens the next day. Christine is. Oh, my God. What’s going to happen? And Calder stays. Spend spends the night making his show. That takes a lot of confidence, a lot of guts to do something like that. Can you talk about that? Was he cocky? Was he glad? I don’t think so.

Alexander Rower The exhibition at Harvard was. It was related to an exhibition he had done in Berlin, and he made a lot of the same types of figures that he had made previously. So he didn’t just get off the train and invent these objects. He made some of the same objects again. Interpretation, you know, it’s slightly different. But basically many of the same types of works. So so you have to understand that to understand really what that exhibition was about. But indeed, he arrived with a roll of wire and pliers. And that shows a tremendous amount of self-confidence, but also ingenuity. You know, here he was and he had his materials and he could spend six hours and make the show, which is what he did.

Interviewer: It also showed he really knew his materials. He really knew what he was doing. They talked about going to a party with his pliers and a roll of wire and making everybody’s portrait. You dont sit there for two weeks and say, well, this didn’t work. Throw it away. To me that’s remarkable.

Alexander Rower Well, he made hundreds of wire sculptures. And in the process of making them from the beginning,.

Interviewer: Start again.

Alexander Rower He made Caulder, made hundreds of wire sculptures. And from the beginning, with his very first wire sculpture in 1925 at this rooster sundial, which now doesn’t exist anymore. He made it for his window. And as the sun came and he could tell what time it was, you know, just this wire, and then he put a little rooster on top. And through the process of working his materials, he knew them so well. He loved his materials. He developed ways of manipulating them and ways of joining them, binding them and so forth that were just second nature to them now. And so to make a whole series of things, he would just sit down and do them, sit down and make them. There’s when he makes a wire portrait, there’s a famous little film of Pathé newsreel asked Calder if they could film him. And in 1929. And he agreed and he invited invited Qiqi Demo Parnas to come and sit. And so he did her portrait as part of this little newsreel feature. Kiki sat down and he did some sketches of her more as a way of trying to decide which turns to take in the wire.

Interviewer: There seems to be a natural progression Calder’s art in one medium to the next. If you look at it all seem related from the line drawing, mobiles, wire sculpture, toys. It all seems related. Can you talk about his style and the relationship and also how he grew. Too big a question. Let’s talk about the how they relate.

Alexander Rower Well, when you study Calder’s work in depth. It becomes very easy to see the progression of his progression as an artist and. For instance, he made a whole series of Josephine Baker’s. There’s one here. This is the last Josephine Baker called Josephine Aztec. It’s made about 1930. And it’s it’s much more stylized than any of the previous ones. The very first one is only about this high and it’s made out of brass wire. It’s one of the first sculptures he makes when he arrives in Paris, 1926. And if you if you consider all the different, Jospehine Bakers as a continuum in just this short period of four years, you can see how they go from small to big. And from. From this. It becomes very interpretive and becomes much freer. The form of the sculpture takes begins to take a precedence to the subject, abstractions beginning. And you can see that through all different kinds of issues in the wire sculpture, where earlier he’ll make a figure that’s a weightlifter and you’ll have a face and later you’ll have a character in a circus scene that doesn’t have a face, just a loop for a head. And he’s refining and just becoming more gestural and working towards abstraction. When he finally gets to abstraction. He he really just drops everything and is now an abstract artist, and this happens around the time that he visits Montreal studio. He’s known Montreal before, but he visits the studio and has this what he calls a shock. And. It’s not a shock related to Mondrian’s painting, but the shock of the environment being in Mondrian studio with a light coming in from both sides and all of the colored rectangles tacked up to the wall. And the fact that the Victrola, the record player is painted and is part of the environment really shocked him. And he went back to his studio and started painting paintings, and for three weeks or so he made these abstract paintings. Which are such a departure, tremendous departure. But in fact, you can relate them to earlier things you can relate them to. This one board that has this wire circus scene. If you look at the board, it’s painted.

Speaker And if you look at just the board and not the figures, it’s this abstract painting. And it’s just prior to this time. And so you can actually bring works in and draw this continuum. But you really have to study it. You really have to see it. It really has to be presented. It’s not obvious if you read the literature. If you read the autobiography, it seems like it’s just bang this moment. And it came from nowhere. And that’s that. Now, all of a sudden, these abstract. In 1931 and 32, he makes a whole series of drawings which are done at the same moment. They’re wire figure drawings of circus performers, of trades people is wonderful, drawing of the engineers laying out a line. Another wonderful drawing far away zebra’s, which has this flower in the front. And these little tiny way way, way in the back. Incredible drawing. And at the same moment, he’s drawing all of these spatial drawings. These spheres and orbs and planet relationships and vectors, and, you know, they’re about density, they’re about those same issues. It’s the beginning of developing truly his vocabulary for the future. But he’s making these two drawings at the same time. This is wonderful moment of tension where he’s dealing with the abstract and the figurative and it’s a process he goes through over a number of years. It’s not just this, it’s immediacy.

Interviewer: Switching subjects completely. Did he feel a difference to the US, in France? Paris in terms of his creativity? Did he do things better there or here or were there? Does it matter? Is not even a question to discuss.

Alexander Rower We’ll Calder chose to go to Paris as a way of achieving a certain expansion. And he did that and he got married in 1931 to Louisa. And they lived in Paris for two years, basically. They came back in 1933 and they bought a farmhouse in Connecticut and I guess you could say that being in Paris was this great moment of expansion and then he marries, then he becomes a little bit more legitimate in a certain sense, he’s more established. He’s known as this this artist who made his famous for his wife sculptures. He’s famous for his circus. He’s famous for his wire sculpture, he’s famous for his circus. He’s not famous yet for abstract sculpture. I mean, his friends, Miro and Leisa and and so forth. They understand what his work is about and they recognize his work. But in terms of the audience, the public, they know him as this circus guy. So when he returns to America, it is kind of a breaking away of the strings that bind him as those wire artist and he becomes even more fully an abstract artist. He starts making his first outdoor works in 1934, just a year after he buys the house in Roxbury. He’s making things for outdoors. Who’s making sculpture for outdoors that you can live within and be involved with. It’s it’s very exciting time.

Interviewer: Did he ever talk to you about art. Explain it and talk. Did he ever.

Alexander Rower We had many conversations. All this yelling, it’s kind of distracting.

Interviewer: Start again.

Alexander Rower Well, my relationship with my grandfather was very close and.

Interviewer: OK, let’s cut. Your relationship with your grandpa. About art.

Alexander Rower Calder didn’t like to talk about his work. He didn’t want to pose these interpretations about his work, but he would. He made it very clear what his intentions were about his work. Bye bye sideways remarks. By cracking a joke. By allowing you to participate in ways that is very hard to describe. I spent a lot of time with him in the studio. I would be in there as a little boy. You know, my brother and I making stuff. He told us which tools to use for what. Which tools not to damage. He had a jewelry anvil. He had a lot of jewelry. And he he had polished the surface for when he was hammering so it wouldn’t get marred. And my brother and I always like to hammer on the anvil just for fun. And he didn’t want us to hammer on that one. So he always leave us a little sign. Don’t hammer on this one and that kind of thing. I think I think he loved that we were involved with his tools and in his space. He loved to have us around, whereas he hated people in the studio. He didn’t like to work when people were there visiting. He never worked when people were coming to see him and see his work and. He never had an assistant in the studio. Another interesting thing about him. Today artists have five and six assistants and. You know, all kinds of other hands involved in the process and outside of the monumental sculpture that were made, it foundries under his direction. Everything was made by him. With his own process at his own speed. Just really wonderful.

Interviewer: The pictures of his studio studios show us incredible chaos. Can you talk about that?

Alexander Rower Well, his studio was not in chaos. That’s the funny thing. He know precisely where everything was and it was his system of organization.

Speaker The sculptures that he stored, many early sculptures were behind other things and wrapped up and tied and preserved and in storage. But they were there. His tools were in certain patterns in certain places, and he made all of these places in his tool bench to to just to park a tool. So it was always at that point, you know, when he was ready to file, the file was there and he had it and he put it back. And it wasn’t a mess. It wasn’t chaos. He had these little stations in the studio to do different kinds of chores. And in the process of making this sculpture.

Interviewer: This cameral 42. This is take three. OK, let’s call it take four. He always seems to like have people around. I see pictures of big groups of people around the table. Can you talk about the social club?

Alexander Rower After the subway goes by I will. Is that alright. The Calders loved people around. People came to stay with them. They would go visit people. They were always socializing. They had great parties that would last for three or four days in Roxbury. People would be sleeping everywhere, passed out. You know, these wild parties. When they came back from Brazil in 1948, they brought all these somber records, had samba parties. I’m very distracted by all of that.

Interviewer: I know. Go ahead. Try again. Go ahead. Five. Came back from Brazil. Samba parties.

Alexander Rower When the Calders came back from Brazil in 1948, they brought with them all these great samba records and they threw samba parties, samba lines, you know, in Roxbury. This crazy, really crazy times had wonderful times.

Interviewer: Let’s talk about politics. He took a stance about things. You know, the early 1966 ad in The New York Times protesting the war in Vietnam. Can you talk about how he felt about things? I understand that Vietnam, Louisa was aware before he was.

Alexander Rower Right. Calder was very politically active. He had great social concerns. But I think more importantly, Louisa was really the driving force in their political activism. When. They were there were both extremely concerned about the Vietnam War, and in 1966, they took out a full page ad in The New York Times against the war. This was the new year and they were calling for a new Europe peace and suggesting that reason wasn’t treason and that you can voice opposition to the government and still be an American still and should be respected as an American.

Interviewer: And he took on other causes, too. I mean, he wasn’t shy about that. I saw in Nicaragua posters.

Alexander Rower They were they were very involved in all different kinds of political and social issues. Calder often made designs to be used to make an addition of lithographs or some other thing, posters from McGovern, when George McGovern was running for presidency. That kind of thing. He was always willing to help out.

Interviewer: This is supposed to be a film that the artist and the man. Yet there seems to be so much of an artist. Besides that he liked to party, and that he iked wine. Who doesnt? And the politics we just talked about. What should we know about Calder, the man.

Alexander Rower With Calder you can’t differentiate between his life and his work. When he goes to the studio. He wears the same clothes he does as to when he goes shopping, you know, or goes whatever he’s doing, he’s wearing the same uniform. It’s completely unpretentious. And if you’ve got some paint splattered on him, which was rare, then that was OK and it didn’t matter.

Interviewer: So there’s no personal to know about him. No.

Alexander Rower He was so tremendously socially minded. He cared about his friends. He supported them. He gave them money if they needed an operation. You know, he was so willing to share what he had. His generosity was really quite overwhelming. Through through in the cat, in the process of the catalog, Rosnay, I’ve now discovered really how generous he was, just how many literally thousands of works he gave away to his friends, his associates, his the guy down the road who cut the field, you know, in Connecticut. That kind of thing. Everybody got something. It’s really sort of overwhelming.

Interviewer: Describe your memory of the parade in Chicago. How old were you? What’s your.

Alexander Rower I dont know how old I was. Calder day in Chicago was. I don’t know.

Interviewer: I think it was 69 wasn’t it?

Alexander Rower Was it?

Interviewer: Seventy one seventy one sixty nine Carson.

Alexander Rower I don’t know. Well Flamingo was the first sculpture commissioned by the General Services Administration, and it’s something very special about it. It was the beginning of that project of the government actually putting a percentage of their building budget into art. And they chose Calder to be the first artist. I think it’s a really wonderful sculpture. That day of the dedication, which which Daley called call her day and gave me a key to the city and all that stuff. It was a huge celebration, but it really wasn’t related to Calder. It really wasn’t about the family. It really wasn’t. It was it was what the city wanted to do. And Schlitz Beer brought out their 40 horse hitch, which was this kind of ridiculous circusy wagon with these 40 draft horses. And it was a big PR event. I don’t know.

Interviewer: That you rode up there right next to him. Was it fun?

Alexander Rower Not really.

Alexander Rower I mean, it was you know, it was a moment. It was. It didn’t really have anything to do with Calder. I mean, again, it was this reduction of an understanding of him. They brought him a circus wagon. He’s going to ride on a circus wagon. They’re going to release all these balloons. They’re going to give Mickey to the city. He doesn’t give a damn about the key to the City. You know, he would’ve preferred to work, but he was an obligation which he which he took on.

Interviewer: Let’s talk about his later. Let’s cut for a second. Are title’s important to him?

Alexander Rower His his use of titles was really a way of keeping track of the work. Very rarely were the titles intended to be useful in interpreting the work they were more a system of. You know, when he would speak to his dealer, he couldn’t say, you know, that mobile I made three years ago that has. It’s hard to describe them. So he began to give them titles, the first titles were more a cataloging nature, a system of numbers and letters and a lot of titles were like that. And that became more difficult too as he made more and more works. So the problem, though, comes in when when you have a purely abstract work, which is called the SEAL. It’s really not a seal. It’s not an abstraction of a seal. It’s not an interpretation of a seal. He made this work without a preconception. And after making the work, upon examining the work in some way, it reminded him of something or somebody else interpreted it in some way. It had a certain shape or a fin or something. Oh, well, we’ll call it the seal of 1958, you know.

Interviewer: Is that a problem?

Alexander Rower It’s a problem in that it minimizes the way that people can approach the work and it reduces possible interpretations. You look at one of these works, and if you know nothing about a title, you have to then bring yourself to the task of communicating with it and trying to understand what it is that you’re looking at and trying to understand what it is he’s expressing. What is this about? Is it just about form? Is it about solidity? Is it about gravity? Is it? What is it about? What are what are the issues being dealt with here? And that’s much more difficult. Of course.

Interviewer: End with. Give me a story. A Calder story. Something with you, personal, funny, sad, poignant.

Alexander Rower I don’t know, you have to ask me a question. So many possibilities.

Interviewer: When did you know that he was that grandpa was a famous artist? That the toys went to be played with?

Alexander Rower Well, no the issue of not playing with that donkey and cart was not because he was a famous artist, was not because this was something that had a value, was not because of any of these external reasons. It was because to me it was a magnificent thing. And to allow it to be altered, even just simply through the process of maneuvering it, you know, playing with it and engaging it with other toys, putting a rider on the donkey, you know, that kind of thing seemed inappropriate, you know. Here was this thing to enjoy as it was. It was basically a line drawing done in wire.

Speaker Thank you. Let’s sit for a moment. Cut. Just going to sit and get.