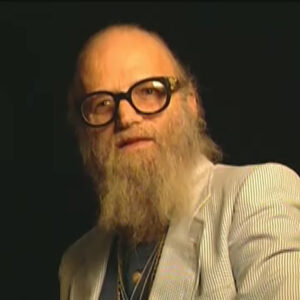

Speaker More burst on the scene in 1937 with a short story called In Dreams Begin, responsibilities that appeared in the first number of the newly revived partisan review. And so he made an instant splash as far as one can make a splash in that rather rarefied but still crucial world. And he was instantly seen to be the coming figure. I know Alfred Case and said he was the power of the partisan review crowd, and Bellow described him as the Mozart of conversation. He had an instant impact in the same way that T.S. Eliot had an impact when he published The Wasteland and that Rambo had an impact in the 19th century. He became a kind of iconic figure, as they say nowadays. And he was only 24 years old at the time.

Speaker It was really the beginning of a short lived but very remarkable career.

Speaker Perfect, perfect, perfect. Don’t give in too much if ever there has to be tighter.

Speaker Saul Bellow, do that little section again about Saul Bellow.

Speaker Just that one. Oh. And Saul Bellow called him the Mozart of Conversation.

Speaker Tell me a little bit about how when you jump ahead to Syracuse. I know what you think I do that some fellow and probably low. Good job there. What was his state of mind at that point? How is that what happened there?

Speaker Yea yea yea yea, I think I, I think I, I read it last night. I just think for.

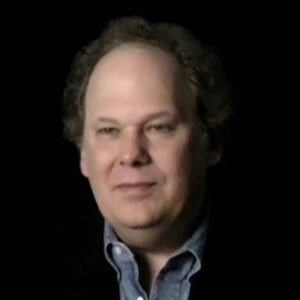

Speaker Unfortunately, we’re down more of the road down was just as swift and precipitous as the road up had been. And by the early 60s, he had already been suffering through an entire decade of ruinous behavior complicated by drug and amphetamine use and alcoholism, all of which is documented incredibly vividly in Saul Bellow novel Humboldt’s Gift, which is really a book for a biographically about Dartmoor and his swift rise and equally swift decline. By the early 60s, he had lost whatever jobs had been he thought had been promised him, including a phantom aspiration to be a tenured professor at Princeton, where he certainly wouldn’t have fitted in. He never thought he fit in anywhere. He just fitted into the mythology of American literature. But in practical terms, he didn’t have a job. And Saul Bellow and a number of other friends. I think John Berryman and others who had followed his progress very closely during these terrible last years. And also the critic Dwight MacDonald recommended him for a job at Syracuse. So he went up there in 1962 and. He was really in a very sorry state then and the very first night on campus in a little motel. He hurt his hotel room as one of his friends put it. After that, things got even worse. He really was in a very sorry state at that point and unable to concentrate, hardly able to teach. And yet he still had the vestiges of this youthful charisma. He’s still as soon as he began reading a poem or talking about poetry. Something in him would be rekindled. And the old Delmore was back. And so many students I talked to and professors from this period remember him as in some ways obviously a diminished presence. But still, with that kind of shining sense of the importance of poetry and the literary life, he still had that sense of vocation to the very end.

Speaker And Syracuse may have seemed like an unlikely place for a romantic poet, but Dunmore was very Roissy and in his sensibility and he thought that wherever he was, their poetry was. He used to tell his students, just walk around Syracuse and it’s like Dad won. And he kind of enjoyed even though he had spent his life in Greenwich Village and in Cambridge and in Princeton, he would look at the filling stations on Onondaga Avenue and find poetry. And I think this was still inspirational to his students, that he didn’t see himself as exiled. But he still saw himself as living in the world wherever he happened to be.

Speaker You could talk about maybe his language accessibility.

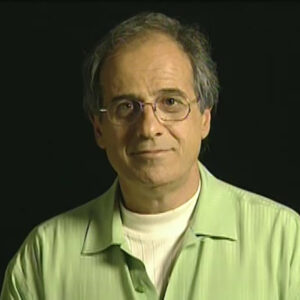

Speaker One of the things you have to understand about Dunmore was how accessible his poetry was that he really aspired to write in the demotic American vein.

Speaker I really can’t think of another power except for Allen Ginsberg, for whom poetry was not a special form of rhetoric, but was the living American language melded with the tradition of English poetry, all of which Dunmore had absorbed from a very early age, so that in his work you would hear both Miltonic grand style and his epic poems. And then the American vernacular. And it made for very startling and beautiful fact. Gorgeous.

Speaker Yeah. So it is the. That little space. Possible, yet tighter. I just don’t know.

Speaker Dunmore spent many years at work on a rather misconceived epic poem called Genesis, which was going to be in blank verse. The heroic story of one Hershey Green from Brooklyn. He wrote volumes and volumes of this book. But he really will be remembered, I think, for the brief form in which he had this kind of compressed eloquence that I think will be his literary legacy. And in the story, in Dreams Begin Responsibilities, that famous stroy that appeared in Partisan Review in 1937. He managed to get the entire story not only of his parents disastrous courtship, but of the Jewish emigration and the aspirations of American Jews into the space of seven pages, along with the poignance of wife, I guess would be the way he would put it. And his short poems, his lyric poems, had that same kind of intensity and compression and the heavy beer who goes with me and his sonnets. He really managed to say everything that he needed to say in a very short space, very effectively.

Speaker Are there any particular problems that you can remember top of your head or any crazy? Uh, uh, uh.

Speaker Uh, let’s see. Well, I just. It’s been so long. Let me see. You can do it later. Yeah. You have the book and I could just get for a second.

Speaker Hasn’t my favorite lines of his are the ones that aren’t out in the famous poems like The Heavy Bear that goes with me or Starlite, like intuition pierced the twelve. But I love his lines tossed off in his journal like I lie in the coffin of my character.

Speaker That’s why I’ve never forgotten to read one single line. Is it anyway?

Speaker Right. It’s just unbelievable.

Speaker It’s the scrimmage of appetite everywhere. Great. And he always wrote these sentences. He wrote these great lines in the strictest classical iambic pentameter blank verse. I mean, he really had absorbed the language to the point where he could say anything. He could write about anything in that same rigid script, Form says.

Speaker Words with journalists.

Speaker Oh, that’s nice. Yeah, I can see that.

Speaker So maybe explain what you think of me.

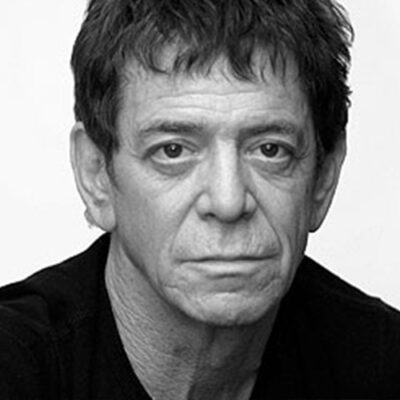

Speaker Let me think. Should I say somebody said someone said Lou read was Dedalus to Joyce’s bloom. And I can see that not only because Don Moore was himself such a Joycean figure who had actually memorized long stretches of Ulysses. But he also was a mentor. He was a great teacher. Not in the strict professional sense or the professorial sense, but in seeing that poetry was a tradition that had to be carried forward. And so when he found young talent and young writers, he was as nurturing to them as writers like T.S. Eliot and Alan Tate had been to him.

Speaker I was going to say, what do you think you learn from more of what you know?

Speaker Maybe that’s really more about what that atmosphere was like there.

Speaker Oh, I know. I could say something about. I think for say.

Speaker You have to remember that the period when Delmore was at Syracuse was the early 60s and it was right before the famous cultural transformation that we would see a few years later after he died in 1966. But in a sense, I feel that his work really prefigured that movement because it was quintessentially modern and also quintessentially contemporary. And it was very much of his own moment. And yet it embodied the classical tradition. And so, in a way, I think he wouldn’t have been surprised by the way our culture unfolded and exploded. It more like it in the late 60s. That was all part of his own sensibility. Maybe in the last few months, the last few years really have done as life were tragic in toward the end of 1965.

Speaker He left Syracuse altogether and disappeared into midtown New York, where he stayed at a hotel called the Dixie Hotel. Living alone in a room and no one ever saw him except by accident. Saul Bellow ran into him on the street one day and saw that he looked so stout and said, Can I do that again? Toward the end of 1965, Dunmore left Syracuse altogether and went down to New York, where he checked into a hotel Dixie. I think I was forty Sixth Street and disappeared entirely from view. Once in a while, a friend of his from his former life would run into him. I know Bellow ran into him in Times Square and left an account of the stout and dusty looking Humboldt in his novel, which he confirmed to me really happened. Otherwise, no one even knew where he was. And he stayed in his room reading novels and writing in his journal and working on his epic poem and occasionally seeing an old girlfriend from Syracuse. And in the summer of 1966, having moved to another hotel. He dropped out of a heart attack in the hallway, and no one even found him for two days. He was in the morgue, as Bellow says, of Humboldt. There were no readers of modern poetry in the morgue. No one even knew what had happened to him. And finally, a reporter from The New York Times, I believe, saw his name and discovered who it was.

Speaker And they had a memorial service. And that was the end of Don Moore’s life, but not have done as legend.

Speaker Any regrets? Yeah.

Speaker We’ll read with one of the students who used to gather around the Shaabi Orange Bar, it was called a campus, a place that I visited myself in my pilgrimage and not a promising venue for poetry, but that’s where they hung out. And Don Moore and his band of students and Lou Reed was among them, along with a number of other writers who later became poets and.

Speaker What do you think went on there?

Speaker All done, more love to tell stories. He was a fabulous raconteur, even in his later years. And he loved to entertain people with body stories, most of them invented about T.S. Eliot and his relationship with his wives and his brother in law about Harvard and ribald stories about Queen Elizabeth and whatever he said. He somehow knew how to tell. And so he was a great. Even when he was no longer writing, he was a great presence.

Speaker Anything else, Karen? We’re getting any word. The only thing you said Reid was rather than Schwarz’s blue, you said choices. Oh, did I say that? OK, well, let’s say.

Speaker And begin passage, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. So I think we have to research.

Speaker I actually didn’t even know that he drank glued to it. Syracuse recognized there and pulled him into the air as possible.

Speaker As possible. I wish I’d known. See, I learned. It’s amazing.

Speaker I don’t know everything. Not much else.

Speaker But you think there’s one thing that you guys are telling me stuff.

Speaker Let me think of that. Oh, here, I like this, everybody rolling.

Speaker Reid said he was down to us, to Delmore Bloom, which would make perfect sense because Dunmore was not only obsessed with James Joyce and with the character Bloom and Ulysses, but he also was a mentor to students and writers younger than he was, and he aspired to perpetuate the tradition by nurturing them. So in that sense, he was a very good bloom to the young Dedalus.

Speaker And maybe you want to read something, right?

Speaker Let’s just think for a second.

Speaker I wish I could remember the things, some of the funny witticisms.

Speaker Let’s see.

Speaker OK, I guess not read.

Speaker What do you read from him?

Speaker I love that you read that. OK.

Speaker I know it is. OK. There’s a poem by Lou Reed called My House, in which he talks about the image of the poets and the breeze. Canadian geese are flying above the trees. A mist is hanging gently on the lake. My house is very beautiful. Tonight, my friend and teacher occupies a spare room. He’s dead. A piece that we asked the Wandering Jew. Other friends had put stones on his grave. He was the first great man that I had ever met.

Speaker I’m very touched by these lines because I never knew more. He was the first great man I thought I ever met. To.

Speaker Well, and in that properly, but, you know, it was great.

Speaker Say, what about why you think it was the first great man you ever met?

Speaker Uh.

Speaker I think what I learned from Dartmoor was that the themes of one’s earliest life are played out forever in one’s life, and that while we change in transmogrify and become other people in our later life, there’s always that essence of the child within us, which made sense to me when I read down your story. The child is the meaning of this life. I think he meant not just children, but the child within him.

Speaker Oh, I know, I could have said. You can say it. I want second back up to the.

Speaker I never knew Delmore Schwartz myself. But in a sense, he was the first great man that I ever knew to because I spent so many years immersed in his sensibility, giving out the life that he had lived in his work. I came to understand that there are a few themes in people’s lives, a few key themes that they play out forever. And whatever the ways in which they change in life, they still grapple with these issues of childhood. And that was really dumb wars theme. When I came to read his story, the child is the meaning of this life. I understood at once that he wasn’t simply referring to children, but to the child within him, the child that Wordsworth said was the father to the man.

Speaker And then if you wouldn’t read anything in particular, I thought I’d read the end of it.

Speaker I just I just casually say, yeah, you know.

Speaker Right. Really? One second.

Speaker My favorite work of Dartmoor is is still in Dreams Begin Responsibilities. The story that made him famous at the age of 24. It’s a very beautiful, simple story about a boy. No doubt Tahmoor himself, who imagines himself in a movie theater watching his parents own courtship unfold on the screen just before they get married and have these two children. No doubt Delmore and his brother. And as he watches them happily engaged in their courtship, then having an argument, he says, don’t do it. What are you doing? Don’t you know that you can’t do whatever you want to do? Why should a young man like you has referendums on married father with your whole life before you get hysterical like this? Why don’t you think of what you’re doing? You’ll be sorry if you do not do what you should do. You can’t carry on like this. It is not right.

Speaker You will find that soon enough. Everything you do matters too much. And he said that dragging me through the lobby of the theater into the cold light. And I woke up into the bleak winter morning of my 21st birthday. The window so shining with its leap of snow in the morning already begun.

Speaker Do we have to make too much of their. I kept seeing it. My thing is there is this paranoia, Delmore is the paranoia.

Speaker But at least you don’t see rock. You look fabulous.

Speaker Is there anything else we need to cover? We’ve got some super one.

Speaker Well, you know the poems here. There are others. Some in this. Know this is just.

Speaker Just stories.

Speaker Previous dentists and.

Speaker Settle down. So quietly. Both of door door.

Speaker I inquired. And OK, so what if you could talk about Delmore, what he looked like when he was young?

Speaker And then also kind of what it looked like described in the Syracuse period. Right.

Speaker I think part of Darmouth charisma when he was a young man wasn’t only in his poetry, but in his looks. I think there was a statistic I remember the great line. Sure it was. Oh, I know. OK. Dump, part of downwith charisma in his youth, had not only to do with his great talent as a poet, but also with his good looks. I know Mary McCarthy, the singer, claws into him at one point and said he was described him as the beautiful boy. Dunmore used to write little poems about other people. He wrote one about Sydney Hawke, who is a rather homely academic type. He said it was his mind and not his looks. Is that why some men study books? Well, this wasn’t true of dumb or was his mind and his looks. And when his book came out in 1938, he was pictured in vogue. There was a fantastic stylized thirty’s photograph of him that showed Delmore the beautiful boy.

Speaker Now, what was tragic was that within a mere 10 or 15 years, he had really gone to seed and become very overweight and shambling. Every time I read that poem of his the heavy bear who goes with me, I think the heavy bear was himself.

Speaker And that’s what he was really like at that point. He was unkempt. And by the last year or two of his life, he really looked like someone who lived on the street.

Speaker Perfect. Perfect.

Speaker I can’t think of anything else parents anymore.

Speaker And I want to grow up. Well, I learned that. New York. Brooklyn, New York. Oh. Oh, yeah.

Speaker Okay. Let me say. I could say about that. You are to be more. Yeah. Yeah. Let me think about that for a second.

Speaker OK. Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker Yeah, I can imagine that Lou Reed would have been entranced by what I would call dumb wars. New York A.. He grew up in Brooklyn and in Washington Heights. And he actually never even left America. He went only to Cambridge and Princeton, New York was his base and was really the essence of his soul. He was always returning back there. Living in Greenwich Village. He wrote of his character, Hirshey Green, and his epic poem. He would say, Oh, New York boy. And that was dumb. Delmore was the New York boy.

Speaker And one more thing I just thought about, there’s the.