Speaker So I suppose I mean, I don’t know about the poetry, but wherever you want to start, I mean, when is the earliest impose works that you begin to see artists taking advantage of his visual richness?

Speaker There are some illustrations, a couple illustrations of his work during his lifetime.

Speaker I think only to the first fully illustrated edition of his works happens in the 1950s. So not long after he dies. But it’s really only in the eighteen eighties that you get really considerable artistic interventions, really impressive people.

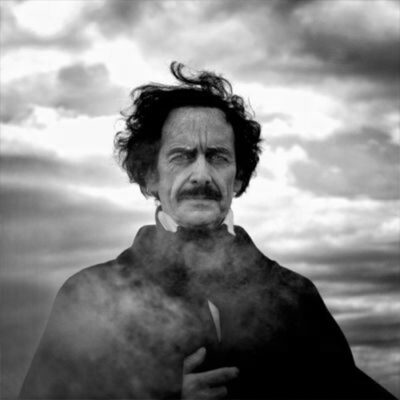

Speaker Manet, for instance, does illustrations of The Raven from Malamud’s translation. And it’s really the 1880 that you begin to get a rich illustration tradition, an artistic tradition. Odilon had all the painter and an printmaker also does amazing things in the early 80s based on Poe, not exactly illustrations, but they are images inspired by and interpreting Poe’s work. A very famous one is just an eye in between some boards looking out at the viewer, and it’s understood that that’s based on The Tell-Tale Heart. But nobody really knows what it’s illustrating per say in the story. So it’s already taken some distance from the stories text. But it’s an amazing image and it’s a brilliant interpretation of Poe.

Speaker And then they go on and they go on in 1890 is in the 19 teens and 1920s with the sort of golden age of illustration.

Speaker Art illustration is 1890 in 1920. And there are Harry Clarkes. The Irish artist does two volumes of amazing illustrations, an Italian named Carlo phonetic who does two volumes of amazing illustrations in the 1920s. So there’s amazing stuff back at that time. Yeah.

Speaker And what is it about, Poe, about post stories or is poetry in some cases that inspires visual artists?

Speaker I’ve been thinking a lot about this and I don’t have a handy answer yet when I do that, not my work for the book will be done. But I think a couple of things. One is, if you look at them and you try to sort out how the visual artists approach the work, there’s two basic strategies. One is the classic illustrator’s strategy, which is to find a moment, narrative moment in the text and try to do it, as it were, kind of a snapshot. Now, sometimes they play with the details of that moment, but it’s pretty identifiable at that moment.

Speaker It’s the other strategy is about atmosphere, I would say, where they’re trying to convey the feel almost a story and they’re not worrying very much about linking up with a particular narrative moment. This issue of Poes atmosphere is, I think, a very hard one to pin down, but I think it’s very powerful for lots of artists, not just visual artists, but very much musicians as well. See, for instance, worked on a treatment of POWs for the House of Usher for many, many years. And you never felt he could get it right. But it’s an atmosphere piece almost. So narrative and atmosphere are the two main strategies, I think. And, you know, certainly with narrative, there are so many striking moments to to choose. But it’s interesting.

Speaker Often they don’t they don’t, you know, watch the last breath going in. And Casca Montejano, they they find some other moments a little bit off of the climax.

Speaker So and maybe going back to sort of during Poes life when Poe was publishing.

Speaker So not so much talking about the visuals, the illustrations or the visual representations, but what was Poe doing that was different from other writers at the time? What? What? Yeah, and not just specifically the detective genre, but more in sort of the atmosphere.

Speaker You’re talking about the putting his finger on the pulse of kind of anxiety and sensation you see touching things other people weren’t.

Speaker Oh, that’s a that’s a that’s a deep question. And not there’s no simple answer to that. I think he what does Poe do that is different from his peers? Well, he is very focused on formal questions. He’s very overt about it. He wrote a lot of criticism, essays on his own craft. And he was very self-conscious about what it was to construct these artworks, how one went about doing it. And he had very decided views about the ways in which the time he lived in made certain requirements on him as an artist. People did not want to read longer things. They wanted to be sure things their time, their attention span. It was already diminishing in the 18 30s and 40s, it’s only diminished more since then and he was very overt about that, he said. Writing a long poem is is an oxymoron. You can have a long poem. It’s a contradiction. Should be no more than one hundred lines of the war. So he was very self-conscious about form. He also was very interested in the generic range available to him at the time. So there was this was an explosion of literary forms at this time. It was kind of a Wild West almost of literary culture. There was a lot of piracy, other writing coming from England mostly, but also France. So science writing on science, sentimental romances, Gothic romances, urban urban mysteries, genre, and the man of the crowd, for instance, and even some of the detective fiction.

Speaker So he was picking up clues from all these things that were out there and then he would make them his own with these sort of formal requirements. And that’s what I think made him so, so unique at the time.

Speaker Great. Thank you. And going back to this attention span thing, I’m glad you mentioned that, because I read that somewhere where his little comment about the fact that I think these magazine stories may be making us all essentially impatient or something. Or do you remember?

Speaker I don’t know that I remember that particular way of expressing it, but he certainly has. He is a creature of the magazine world. He wrote only one longer fiction. It was at the behest of the Harper brothers who said you should try to write a consecutive narrative. We will publish it if you do. And what he wrote was Pimp the narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym Nantucket, which is not successful, and it was not successful in sales. It was not successful in being a consecutive narrative that everyone would recognize as the novel is a strange amalgam of different kinds of genres. Again, different ships, logs, fantasy, cannibalism, exploration, all these various kinds of of genres all jumbled together. So he had been asked to do that, but he ended up writing a whole bunch of short sections and stitching them together almost in one novel.

Speaker Could you talk a little bit about his awareness or at least his you know, that he seemed aware that attention spans were shortening and that, you know, he didn’t lament that he recognized it and addressed it?

Speaker Well, I think I mean, you have to sort of read between the lines sometimes about this. He does talk about it that you need to be able to read to have full effect, he says, to have unity of effect, which was his goal. The reader needs to take in the story or the poem in a single setting. That’s his. He is explicit about that. And so for that reason, you need short, short stories and you need short poems. Why that so has to do simply with the culture that he was living in. He doesn’t go into great detail about that culture, but it was a culture of magazines. It was a culture of people picking up relatively cheap publications in train stations, et cetera, and reading little bits and pieces over and over again. I think if you watch the development of his of his short story writing from the 30s through the 40s, you’ll notice that it gets more and more compressed.

Speaker Bernie’s a very early, incredible story is pretty long and pretty diffuse. House of ushers. Pretty long. William Wilson. Pretty long. These are all eighteen late thirties, but Cascino Montejano late 40s near the end of his life is eight pages. It’s very compressed. So when he was attacking the short story in particular, he got better and better at his craft.

Speaker I think I think I said this in a conference just now. I think Castlemont is probably the most perfectly constructed in stories and is among the shortest.

Speaker And can you talk a little bit about his his conflict, his own conflict between wanting to be a popular writer, wanting to be a successful writer and wanting to be a highbrow man of art?

Speaker Yeah, it was a well, part of the conflict was simply economic. He was not a well-to-do person. He was an orphan and then fell out with his with his stepfather. And he just always needed money. Ultimately, he inherited a.

Speaker Part of the nobility of art and time and a culture that had not inherited that American democracy in the antebellum period was rough and tumble and it did not have a lot of space for genteel arts and literature. So and Poe was not ever going to be invited into the Bostonian world or even the upper class New York world. But he had inherited it from the romantic writers that he most admired, a notion of the almost sacred mission of art. But he realized he lived in a world that didn’t care for that.

Speaker So there you go. It was rough.

Speaker That’s correct.

Speaker So can you talk a little bit about what these burgeoning cities were like and the anxieties that were arising in urban populations and this idea of immigrants, people from different countries that look different, different languages and neighbors that you don’t even know and we’ll never get to know could be murders for all you know, and how Poe was putting his finger on those anxieties and using them and at the same time kind of feeding them. Yeah, yeah.

Speaker If you look at Poe’s stories in particular, you’ll notice a couple of things. Repeat themselves over and over again. There are very constricted spaces, rooms, sometimes houses, but lots and lots of rooms that seem to be very closed off from the outside world, but that are not that are ultimately are invaded or or explode out. The ultimate room and pose fictions are graves or tombs that you think are about as sealed off as you can imagine.

Speaker But the people come back from it. That spatial phenomenology, for lack of a better word, of constricted space that is in fact invaded or explodes out, I think is responding to a newly, newly sensitized attitude towards crowds in the cities. And you can see this same phenomenology in some of the urban fiction of the period where there are cellars where nobody can see this looks like a nice bank or a nice, very respectable house. But in but in the cellar, there are nefarious deeds going on, et cetera, et cetera. And people who think they’re safe in their rooms are not safe in their rooms. If you read the the one tale where Poe really full on takes takes on urbanization, but I can think of as the man of a crowd and one of the things you get when you go back and read the literature about antebellum New York City is what how plaster of the city was suddenly plastered with language advertisements, posted papers everywhere. There were words to read, so it became a the city became almost a text to read that sort of assaulted you. And we’re used to this now. We go down the street in New York and we’re surrounded or Tokyo or we’re surrounded by language that’s yelling at us almost. But it was new and antebellum New York and very striking to people in the manner of the crowd. He portrays the his effort to follow the man of the crowd as a kind of reading a book. And he says there are some books that do not permit themselves to be read. That’s what he says about the man in the crowd. So you can see that he’s working out the requirement to read the requirement to decode the city and the impossibility of doing that at the same time. In that story, it’s an allegory of life in the city, it seems to me.

Speaker That’s great. Thank you. That’s really, really nice in that in talking more about the whole claustrophobia thing in the title of our film. Is Edgar Allan Poe Buried Alive? Right.

Speaker So in your mind, what was the what was this thing with him about being buried alive, premature burial? Where did that come from? What was it about? Was it personal to him or was that something that was universally.

Speaker Well, it was it was certainly not personal to him. There’s a lot of evidence that there was an anxiety about premature burial at that time. There were people who fabricated caskets with little polls so that if you happened to wake up, find yourself buried alive, you could pull a little bound up above ground. The bell would ring. And so I would know. So there was anxiety. It was a cultural anxiety. There was an anxiety about grave robbing because medical schools, dental schools did did this, they needed cadavers so they would dig up usually, of course, poor people’s graves for it. It’s it’s never been clear to me that Poe had a deep psychological need to think about being buried alive.

Speaker There have been a lot of people who have suggested that he did, that this was related to his own finished mourning for all the people who died on him, his mother, his wife, that this was a way in which he was revisiting almost as a traumatized person, the his inability to mourn and to get over the loss.

Speaker That may be true. You know, it never has felt that compelling to me. What I see him doing with this motif has a lot to do with form. Again, formal matters of constructing tales. Poe’s narrators, especially in the horror stories, are kinds of artists. You know, to Quincy, wrote a text poem called Murder because as one of the fine arts and OPO, I think, understood these these narrators that narrator The Tell-Tale Heart, observe how healthy and how calmly I can tell you the whole story. Check this out. I figured it all out. I had it all planned. Or the narrator of the council, Amontillado, I knew exactly what I was doing from the beginning to the end. I am a kind of an artist and I’m creating a text, if you like, or an object that happens to involve encrypting people or entombment people. They’re artists, but they’re all always failed artists. The heart makes the noise from under the floorboards. The cat cries out from above the head of the of the murdered wife at the end of Casca Amontillado, the jingling of the bells in a sense. So Spook’s the narrator that 50 years later he undoes his work by telling the story of the murder that he committed. So they’re there allegories of the failure of art at some level over and over again. And I think the crypt that speaks to you, the dead that come back to you, is the the most powerful distillation of a story that is not finished properly, of a story that has failed to have closure. So it has a poetic or aesthetic function in these tales over and over again, quite apart from whatever psychological power it may have had for him.

Speaker That’s great. We should add Edgar Allan Poe buried alive, unfinished business. Yes, good.

Speaker He was really and he used the narrative power of contradictions, of death and life and beauty and death and funny humor and horror and all these things.

Speaker What do you make of that? Again, it’s a it’s a it’s a really deep and almost unfathomable question. I think you’re absolutely right. I do think that he used contradiction as the engine of his fiction making, particularly as fiction, though I think it could also be said that something like The Raven is a text of contradiction in that the bird intrudes on his life and the narrator constructs a poem around the birds statement and and winding it tighter and tighter and making himself more and more pained by the result.

Speaker So there is a sort of masochism or self-contradiction in the construction of that poem, as it’s told. You know, he had had a theory of the perverse, which is probably the greatest distillation of the question of contradiction. And he goes right to the to the whole heart of the very notion of motivation. He says there are there is motivation that is not motivated. And he gets all Latin on us and makes it put it into Latin. And he says the perverse is the need to perform an action because you know that it is not right. So you get again, you get a kind of an abstract, almost an abstract version of this contradiction that that exceeds any questions of morality and indeed exceeds any question of psychology and into some sort of almost a philosophical level.

Speaker And you see it. I think the source of your question about contradictions is you see it over and over and over again as the kind of engine of the tale itself, people pursuing things that are not in their own interests.

Speaker And you’re right about the tone, the tone as well. I mean, especially in the early DPO where he’s working through a number of different inheritances from, say, the Blackwood’s sensation fiction tradition. He treats things in really kind of savagely parodic ways, things that are very serious to him, and that mean a lot to him. So he does a lot of work later in his life on the senses, on eyes and teeth and sounds and breath in an early tail loss of breath, which is a sendup of Blackwood’s fiction. The narrator’s the main character’s breath is stolen from him and stuck in a drawer. And it’s an absurd, completely absurd. And he in his neck breaks and his head is cut off and he continues to work and operate.

Speaker So it’s it’s this contradiction in absurdity at that point. It’s very grotesque, but it’s also meant periodically. So he does have you’re I think you’re right at that contradiction is a central engine of the work. Yeah. Good sound.

Speaker So I know you’ve been writing about this, asking about this without getting too arcane, because I’m going to do that. But how does he use it? And is that different from other writers of this period or was he doing something new or was he just doing it better?

Speaker I think Poe’s approach to sound is among the most original things that he did. Of course, he’s not unique. I mean, you can find all kinds of things.

Speaker Do we have to start over that and.

Speaker Good to do. Yeah. That horn was sound OK. It seems to have gone away.

Speaker I would say the oppose approach to to sound as a narrative element is among the most unique things that he offered. Others were using sound. They were using voices in whispers and and whatnot. But if you look at the full panoply of sonic effects and Poe there they are a lot about inhuman sounds. They’re the cry of the cat from inside the grave. They’re there. They’re the heartbeat. That’s human. But it’s not speech. They’re it’s the birds nevermore croaking out. There’s strange sonic effects that are not that are larger than human speech.

Speaker That’s what I would try to say. Human speech falls into is a subset of these sonic phenomena. If you look at the facts in the case of Mr. Valdemar, the man who has mesmerized on that, the point of death, he is kept alive, as it were. Mesmeric for seven months, and he ends up being able to speak in a voice that describes in completely weird, contradictory ways as both glutinous to the touch and very far away. And he says things that are impossible for humans to say. He says, I tell you that I am dead. This is an example of using the sonic phenomenon to push the barriers of the world that he’s describing beyond what is possible, beyond the normal human sensorium. So it the so sound occupies a place in his poetics of limit. It’s a limit case place.

Speaker Either the stuff is impinging from the outside, as in the bird arriving in the window and croaking or the bells in the story of how he wrote the bells, or it blows the tail open from the other end. As, for instance, the cats cry from within the bricked up grave. It is it’s a it’s a limited phenomenon. And for that reason, it’s really interesting to trace how he uses it.

Speaker And then give me the example of the Cask of Amontillado, because we’re probably going to have an actor read the beginning and the end of that. OK, imagine if you’re coming in at the very end after we’ve just heard the end of the story.

Speaker Yeah. So the way I read the way I understand the the effect of the Catskill Mountains start over, the way I understand the effect of the Casco macchiato is that the final Jinling of the Bells is well, I think it’s the most effective single effect in all appose fiction. The narrator has tried to keep his victim face to face the entire time he looking at it, he sends back his words exactly verbatim. When the victim begins to yell after he’s already been chained, the narrator redoubles and echoes the yelling. So we’ve moved from words to just sound.

Speaker But all this time, the narrator is trying to control through duplication what the victim is doing at the very end. The victim is no longer visible, so there’s no face and the narrator says Fortunato. And here is nothing, Fortunata. And he throws the flame inside the crypt, that is that he’s constructing. No, all I hear is in reply to the jingling of the bells. This is the moment in which the the narrator’s ability to control his fiction, to control his artwork, if you want to call it, breaks down. And an area says, my heart felt sick. And I think that it’s because this jingling of the bells is in a sense, completely unplayable. We cannot understand what it means. It doesn’t mean resignation. Is it supposed to be grossly ironic? Is it is it a message of some kind? I think we can’t decide. So in that sense, it exceeds the narrators and Poe’s ability to contain the meaning of this fiction. And in that sense, it’s dedicated to us in the future. It’s not something that is stuck in its time. It’s the little jingling of the bells is immortal. In a weird way, I think it makes my skin crawl every time it makes my. It gives me shivers and I don’t know that I’ve explained it very well, but I do think that there is this structural function out of the sound. And this this final the jingling of the bells is it’s subtler than the cry of the cat, but it’s performing this or the heartbeat, but it’s performing the same function of blowing open the tail at the very end of it.

Speaker Does that help? Yes, that did it. We look at one at a time. So keep your comments confined to that one.

Speaker Speaking of one illustration that I’m very fond of is Odilon hurdles. It doesn’t have a name. We don’t really know what he called it. It’s an eye hanging in black space looking between two four words. You think there are walls when you first look at it and you think it’s the narrator of The Tell-Tale Heart looking, opening the door a little bit and looking in at the man with the vulture eye, then you look at the picture again and you realize that these wooden boards are not walls, they’re floorboards. They have nails in like floorboards. So now you’ve got to think about the eye coming up from from below. But of course, what comes up from below in the story is the sound of the heart. So it’s a it’s a strange sort of almost an interpretation of the story, taking the contest between the eye and the heartbeat, sound and vision that the story enacts and making it all visual. And as a visual artist, you can see why he would want to do that. You’ve got to somehow translate things into the visual medium. And radar has done so in a quite a mysterious and effective way, it seems to me. Another telltale heart illustration that I think there’s something quite similar is Harry Clarke’s black and white. He has two illustrations of. One is a color image, which is very famous, is used as a frontispiece for his edition. But the black and white illustration, I think, is even more amazing. It’s it’s the narrator again and under underneath him, under the floorboards is the murdered man, the man with the with the vulture eye. And coming out of the under the floorboards is what looks like an organic something. It’s a plant. It looks like a plant. But in fact, as you look at it, the plant is made up of both eyes and hearts. Sometimes the hearts are iconic. They look like, you know, I heart New York. Sometimes they look like maybe the heart that we actually have as an organ with our aorta and all the rest going on. But it’s mixed with eyeballs coming out of the floor. And so it’s a it’s again, like there at all. It’s a visual attempt to interpret the contrast between the eye and the sound, between vision and sound, that the story itself plays out. But in a purely visual medium, it’s a brilliant, brilliant interpretation. And for NAFTA and the the FINERTY illustrations are astonishing, there’s two volumes of them. He illustrates almost every major story by Poe. The one that sticks with me over and over again is a scene in the facts in the case of Mr. Valdemar.

Speaker It’s the scene in which Wildomar says, I say to you that I am dead. Please either wake me up or let me die. I say to you that I am dead. Poe describes this voice as glutinous, as coming from very far away. It’s a disgusting sounding voice in that regard. Farnaby.

Speaker Depicts this moment, if you like, by having Wildomar, his body across the very top of the page, the print is underneath it, but falling out of the image of the body lying on its bed is a whole sort of flow of of where it’s not unclear what it’s a flower, but it rips apart the typeface. So literally, the page is cut in two by this image of a sort of dissolution coming out of Voldemort’s body and then pulls the bottom of the page. And there’s a kind of a spooky creature that looks like he’s looking out from it. It’s a it’s a brilliant example of how the visual means can take on typeface and say we’ve got another element here, which is just art. It’s ripping open the book itself. And that’s what that’s what the voice of Voldemort does within the text. So, again, it’s an interpretation of Poe’s use of the voice within his fiction, now translated into fully visual terms. You need to see that it’s very, very hard.

Speaker Will be seen, OK, we’ll be seeing I don’t want to look it up right now, know it’s going after our phone call. I looked him up. I hadn’t heard of him.

Speaker And I meant ask Susan Taine if she has she has any, but she does. So I think I just need one more of fairly short and concise statement along the lines of how why it is that Poe inspired visual artists to do these things and, you know, maybe without dates or anything, just that, you know, it was much or more than any other American author seems to have inspired visual artists to take him on these. He issues an invitation. Yeah, something along those lines.

Speaker Yeah, well, I think he issues it and I think Poe issues an invitation. I just start again. I think Pope issues an invitation to lots of different kinds of artists in lots of different kinds of media. There is something about the way in which the tales themselves have these powerful effects that are relatively isolated and that can be sort of grabbed and put into a different form or a different medium. And it’s almost as though he builds these little structures with identifiable and very vibrant elements. That’s part of it. The narratives are very powerful and because they always sort of show themselves breaking apart because they are failed arts, in some ways the feeling is, I think for artists later on, there’s a bunch of tools that have been put on the table and they are adapted for reuse. You know, you can take it if you want to do the sound of the bell or if you want to do the look of the eye looking through the window, or if you want to do a crypt opening up, you can do that in lots of different ways.

Speaker It’s almost beyond the medium of literature. And that’s why I think he’s been remediated so promiscuously. I think if you look at the visual artists in particular, you’ll find that they they are very focused on these moments of isolated effect.

Speaker They that because a an image has a kind of temporal status, they they’re going to go to these moments where there is an eye hanging in space and there’s no narrative necessarily attached to that. But it is capturing something about the larger story itself. There’s a so the formal focus and the elemental quality to poetics, I think invites reuse by visual artists, but also by sound artists, by film artists, by comics artists. And you’ll see again and again they zip they zero in on on like these isolated moments and close ups, they’re almost like snapshots and post stories give you that in a very powerful way, that the narratives are reducible almost to snapshots in a way that, for instance, the novel is not. And I think that’s one of the reasons why he’s been redone so often.

Speaker Good. Oh, yeah, that was good. Yes. OK, I think we.

Speaker So do this handful of images, how has that fed into creating the power myth, the power image?

Speaker It’s a chicken or egg question, right? It does the myth come first or does the image come first? I think it has to be the case that the myth latches on to these images and the images of pope resonate with what the tradition has wanted him to be. He was obviously a very unhappy person. He had had an unhappy life. He wrote very grisly tales, but he also wrote very beautiful works of art. And he’s always been subject to a kind of biographical reading from the very beginning, from Griswold’s treatment of him upon his death, which is a little bit of a character assassination, as I’m sure you’re you will explain. I think he comes to stand through the tradition for an approach to art. And for that reason, his name and his vision become visage become to say that again. And for that reason and for that reason, his name and his visage become shorthand, as you say, iconic. And that version of art is one that is violent outcaste, mournful, but also popular. He is one of the very few figures in the American tradition, at least, who has been kept alive by popular.

Speaker Arts, sorry, Jen, we can hear you, can you can you just say that last?

Speaker But again, he is one of the he’s one of the very few, OK, is one of the very few artists of the American tradition who has been kept in the tradition by the people. He’s not a figure who’s been curated by academia or by the high art tradition. In fact, they’ve had trouble with him. T.S. Eliot had notorious trouble with him. And many of the arbiters of taste in the late 19th century in America had trouble with him because he was popular at some level.

Speaker So I think the iconic status of his name, in addition to his face, are testimonies to that popular status. If you see some of the films that were made in the 40s, 30s, 50s, they were it says Edgar Allan Poe. And there have nothing to do with his work as just to name the name is enough to evoke and invoke all the set of associations with the grizzly and with the popular at the same time.

Speaker And why is it that his biography, his life story and his work are so often conflated? I mean, even going back to, I think 1910, one of the first movies ever made called The Raven, which actually was purported to be a biography but wasn’t right.

Speaker Again, I don’t feel like I’ve ever really understood that well enough, but I do think it goes back even earlier than that. 1910, when Griswold introduces his work, it’s in the context of his biography, not entirely unheard of at the time. I mean, people understood work to be an extension of the of the person. I think Baudelaire has a lot to do with how this works, and especially in France and in the European tradition, made Maypo into the absolute type of the poet Modie, the cursed poet. The poet who inveighs against his society, who fights against the society. Who condemns a society whose outcast by his society. Poe was never really that kind of a person. The record doesn’t really bear that out. But but Baudelaire made him into that. And so he becomes that in many ways for subsequent generations, especially European admirers, of which there are many, many in many countries. But so I think his mournfulness, the sadness of his own life, his powerlessness and the fact that he wrote the kinds of things that were not widely admired in his day, at least not most of them, and yet have proven deeply enduring, makes him the type of genius that lots of people want to think about in terms of romantic artist.