Speaker Fairyland. Dim veils and shadowy floods and cloudy looking woods whose forms we can’t discover for the tears that drip all over huge moons, their wax and wane again, again, again, every moment of the night, forever changing places.

Speaker And they put out the starlight with the breath from their pale faces, about 12 by the Mundial, one more filmi than the rest, a kind which upon trial they have found to be the best, comes down still down and down with its center and the crown of a mountain’s eminence. While its wide circumference, an easy drapery falls over Hamlet’s overhaul’s wherever they may be, or the strange woods or the sea over spirits on the wing, over every drowsy thing, and buries them up quite in a labyrinth of light.

Speaker And then how deep, deep is the passion of their sleep?

Speaker In the morning, they arise and their money covering is soaring in the skies with the tempest as they toss like almost anything or a yellow albatross, they use that moon no more for the same. And as before, they released a tent, which I think extravagant. It’s atomize, however, into a shower disfavour, of which those butterflies on earth who seek the skies and so come down again, never contented things have brought a specimen upon their quivering wings.

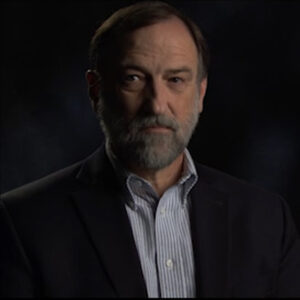

Speaker All right, it does make a difference to hear it. Yeah, yeah, it’s a poem. Yeah. Um, so how did you discover that poem? What’s the story behind it?

Speaker The poem was pointed out to me by Elizabeth Bishop, my new somewhat and Elizabeth heard me making a sort of exhale.

Speaker Let me interrupt. I should have told you so. Just talk to me, OK? Good for them. Yeah, they’re they’re just dumb. Let me explain. I’m going to readjust here.

Speaker Just posted that video that Lisa Bloom made of my poem they put on their site. But now I ask again, I know you don’t have this.

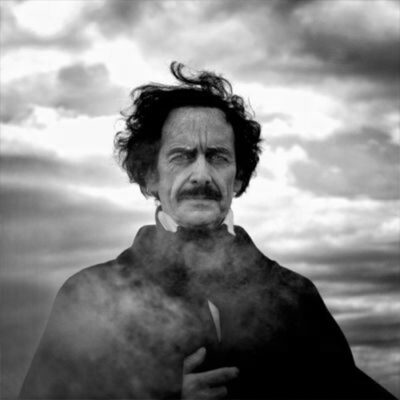

Speaker I must have read Fairy Land by Edgar Allan Poe at some point, I don’t think I absorbed it. And in conversation with Elizabeth Bishop, I made some as many a poet in my generation made I made some slighting or ironic or condescending remark about Edgar Allan Poe. And Elizabeth chose not to be amused. And she said, you know, Robert, you really ought to read Fairyland. And I did. And it gave me a new enlarged appreciation. Of Poe’s mind and how rich and large his imagination was, Elizabeth didn’t say this, but reading it, I thought that.

Speaker Pope in fairyland, quite possibly inspired bishops, great poem, The Man Mothe. Which is impressive and the way he imagines a planet or a place with many moons and then at night one of those moons sort of dissolves and becomes a tent, and that whole place sleeps under the tent, which is just voluminous, enveloping silver cloth. Then it dissolves into its atoms and the atoms are the pollen on the wings of butterflies. There’s a largeness, largeness of imagination that remains quite impressive to me. I’m grateful to Elizabeth for correcting me.

Speaker Oh, did it did that rediscoveries send you to read other poems and make other new discoveries in a way one should have known?

Speaker I should have known that there is more to him than jingle jangle in the bells of the Raven. And I should have known that from the fiction.

Speaker And I, like many people, I thought pose a poet was best in the French translation. Tom Gordon has a famous epigram to that effect that the only single, barely rendered English version is the only example that isn’t so great. I think I’m emphasizing the word large, partly because. Like Emily Dickinson, whom he resembles in just about no other way. Poyan Dickinson is kind of premodern or early Modern’s or the first Modern’s. They embody that quality of modernism, which is tremendously ambitious, see the whole world, see everything there is, see everything there isn’t as well, and see it full and in very large scale. And a lot of contemporary art for me is belittling. It’s either belittling in a kind of middlebrow jovial way that chuckles and says nothing is all that serious or it’s belittling, belittling in the opposite direction in a kind of. Postmodern, where it’s the postmodern and the anti modern, and they both are deprecatory, they both belittle and DPO like Dickinson and like the later Eliot Stevens, Marianne Moore, they’re going for broke. It’s total, and when he’s making his assertions about Fairyland, he’s not holding anything back and you as the reader, can’t feel there isn’t anything that might not happen.

Speaker Do you know much about how his poetry was received in his time?

Speaker I know that he got into tremendous fights with people, I know that he was accused of plagiarism and probably committed a little plagiarism, that he was very much a journalist and that he certainly never made as much of a hit as he would have liked to.

Speaker He did have a mission, a self-declared mission of elevating American literature to put it on on the same level as English literature and not have it be just a parochial national. Voice, But to really make it an international voice, I mean, do you feel like he was succeeding and that from what you know, Paul represents what you might call two different attempts to create a great American literature.

Speaker And. A wonderful writer and person. Longfellow. Was extremely popular. In this country and also in England, queen of England was very excited Victoria was going to meet Longfellow himself, the author of Hiawatha. And as recently as you know, the young Rose Kennedy’s kids all memorized the midnight ride of Paul Revere. In some sense, it was popular and it failed, as many things are that are popular. They’re popular for a generation or two. And Longfellow’s approach was to create American myths. So that Paul Revere. Hiawatha, he was going to invent the equivalent of European mythology, but make it indigenous turned out that didn’t have a lasting impact. The other direction was to create something a lot like European continental literature, indeed, often to set things either vaguely or quite specifically in Europe that was more successful in the end than either one was. Whitman, who created an American poetry and indeed an American art that catches it isn’t a matter of the content of the mythology. It is in the matter of a simulacrum of something else.

Speaker He did the equivalent of opera and he did it in a sort of a language of himself. And those are three fascinating attempts to do the same thing. I suppose still continuing at this point. It does seem that Whitman got it right in a way that Longfellow in one direction and Poe in another direction made memorable works, wonderful works. They didn’t get that idea of making a great American literature right. In the sense that Whitman apparently did.

Speaker That’s really interesting. That’s great, thanks.

Speaker Why do you think, though, as you described yourself, your generation of poets than many before, you dismiss Poe on some level, did not take him seriously?

Speaker There’s no question that Poe did write a lot of pretty corny things. So I’m not abandoning the somewhat shallow wise guy attitude that Elizabeth Bishop corrected and. If your idea of literary art was formed as it was for me and my generation by. James Joyce’s portrait of the artist as a young man by T.S. Eliot, essays by pounds, literary essays and the Cantos, if the idea of HD and William Carlos Williams and Poundland College together and Pennsylvania being interested in hard edges. Kind of a scientific accuracy economy. And getting rid of kind of a 19th century Florida.

Speaker It would be very easy to put people on a pretty dusty shelf.

Speaker I’m sorry if I bounce back and forth and it’s no problems, if you don’t mind thinking back to Poe and it’s time. I mean, he was miserably poor, worked his butt off, from all accounts, incredibly prolific in a number of words and articles and. Yes. Yeah. And yet poverty stricken always. Can you talk a little bit about what the life of a writer was like in the early mid 19th century?

Speaker Probably not. I don’t have a lot of scholarship or information about. People who tried to earn their bread with writing, it was still somewhat disreputable idea, as I get it. Poe had this peculiar relationship with a family where he sort of was and sort of wasn’t part of the family. There’s a certain amount of money. There was a certain middle class context. And he seems to have been one of those people who knew how to make a mess of that sort of thing. There was certainly an improvident self-destructive streak in the man, and it takes imagination.

Speaker Just start to picture him. Experimenting with or maybe West Point, the army might be a good place to talk about imagination, he imagined himself as becoming an officer in the army. I don’t know what I don’t know of other I know this was Trivers or various people who had rivalries and alliances with my impression is that like those late 16th century wits and writers in London, the 19th century Americans were a kind of ne’er do well, hard drinking lot. There must have been some people who made a good thing of it. I don’t know about them.

Speaker Fear for not knowing much, you know, pain is a very. My profession is talking about things I don’t know anything about. You’re very good. That’s my I’m going back to what you were saying about the precursor of modernism in his his potch, some of his poetry.

Speaker I guess we could talk a little more about that. What did that mean and where did that put him and how did it put him in step or out of step with those times? And why has that been an important contribution to American literature over the over the years?

Speaker It’s interesting, you pose often credited with inventing what sometimes seems the main literary and cinematic and video genre of the detective, the crime story. It sometimes seems that it’s unusual to have anything but a crime drama that if you want to think about society, you have to think about crime. There’s something regulatory about cultural products that are on a mass scale, like a lot of video. And Paul was interested, as was Whitman and Longfellow. He was interested in the mass scale. And there’s some I have not read a good analysis of it, an explanation. There’s some connection between storytelling and the police, it seems particularly a 20th century and early 21st century connection between storytelling and the police, something that’s regulatory. At the same time, when we say the modern, we think of something that breaks old structures. That the modern modernism, there’s still maybe some wisp of the transgressive about that very word, and in Poe, when he starts writing this poem about this place with 12 moons and one of the moons every night comes down and makes it tent. And when it dissolves, you find it on butterflies. The audacity and peculiarity of that, if you compare it to the relatively naturalistic narrative.

Speaker Of a Longfellow narrative poem. It is transgressive.

Speaker And disruptive in a way, too, I suppose, to use that word, contemporary terms.

Speaker I mean, he was yeah, you can see why he was interested in the police and he was interested in the figure of someone, perhaps not so much a part of crime dramas anymore. But there are even if you watch, you know, any of the 7000 law and order spinoffs, there’s often a guy who sees things other people don’t see. And when Poe invented. That character, that figure. The predecessor of Poro or Holmes, he was inventing a kind of artist in reverse person who sees what’s hidden, and he does it to bring about the correct order of things. And Poe, he wanted to see what was hidden and.

Speaker Disrupt the correct order of things. Interesting.

Speaker So I don’t know how much of this, you know, but in 1875, Poe’s coffin was dug up from its obscure location in a Baltimore churchyard and moved to the front of the churchyard and a monument up that have been paid for it through pennies, pennies for Poe and Whitman came to the ceremony and didn’t speak, but wrote later about it. I mean, do you know much about know about how Whitman felt about it?

Speaker The.

Speaker I’m trying to get somehow get more about those poetic voice and how it was different from what else was going on at the time, and I don’t quite know what question.

Speaker I’m probably not the right person to ask. OK. All right.

Speaker What was going on at the time is not something I know much about. Yeah, I have actually had the impression what was going on at the time was a lot like what he was doing.

Speaker Oh, really? Even these dream. But I don’t like. Yeah, I mean, just not as good. Or how about can we talk about the raven. Sure. So.

Speaker Why, what kind of poem is that? Is it a good poem, is it a bad poem? Does it matter, given its impact over the years?

Speaker I guess that the raven is on the evidence, a poem that has something speaking as somebody who actually does read poetry for pleasure and not just contemporary poetry. I do pick up I’m capable of picking up Paradise Lost and reading some of her pleasure. I certainly read lyric poetry of every period for pleasure. The Ravens not on my playlist. Uh, I’m not eager to debunk it. I don’t want to take pleasure away from people who do enjoy. The figures have sound a lot of people enjoy a lot, seem kind of clunky and repetitious and obvious to me, and the refrain becomes intolerable for me, says, oh, here it comes again. And it’s a little bit like an escalator comes that one. There was a little piece of gum stuck in it again. So I’m not a great fan of The Raven. I’ll I’ll stick with Fairyland as being a superior poem to the Raven.

Speaker I’m not I’m not of the school that thinks you must correct people’s taste. The people get a kick out of the rave and that’s good.

Speaker And at the time in 1845, it was a huge hit and it made them a kind of pop star overnight. Yeah. What do you think appealed? What made it such a hit?

Speaker I if if I were good at knowing what made things hits the way the Raven was a hit the way when I was a little boy, Lawrence Welk was a hit. All the things in my life that had been popular. If I understood it, I would try to do it and then live off the proceeds.

Speaker So I don’t think I’m very good at understanding what makes things popular. And there is this odd way in which. If you lived to be as old as I am, you see a lot of things be very popular and then not and some things even pop up again that were down. It really is the traditional metaphor for that as well.

Speaker And I think Paul was a great genius.

Speaker So I’m glad to see the will lift him up again. And it’s a pleasure also to say, you know, some of those things that will, I don’t think are so great. Did you ever read Arthur Gordon Pym is I forget the whole title ventures, a narrative of Arthur Gordon?

Speaker It seems to me at some point I did pick it up and read it. I’m not going to have anything smart to say about it. And I doubt you’ve read Eureka. I have not read your book. I have yet to find anybody to have. There were people out there, but I have a copy.

Speaker All right. We’ll be here till tomorrow. Oh, and how are you doing? Are you OK? I have like in about ten minutes, I get a little nervous. You know, that’s fine home in Boston. I mean, what do you think about the sudden adoption or adoption of PO by Boston?

Speaker What does that speak to and why is it happening in Boston for what is it, 150 years now has had this literary click that changes the personnel change. But there’s still this idea that Boston, New York is evil because it controls publishing and money. But Boston is evil because it controls ideas or art. That idea has surprisingly long history. I guess it is probably almost a couple of centuries that it’s been going now and.

Speaker People pretty much a southerner, certainly not a transcendentalist, had his tussles with the Boston literary scene and I’ve already talked about that, good to say, already talked about, you know, when I had my conversation with Elizabeth Bishop, who knows? I’m not from New England. I’m not from Boston. I’ve lived here a long time.

Speaker Maybe my.

Speaker Maybe my character is somebody of the generation inspired by the modernists, was somewhat infected by a Boston attitude as well. I’m not aware that it was, but you could argue that. And it was great fun to see. I think it’s one of the nicest pieces of public art that I’ve seen in a long time. Is that post that you’re now right there, right across the street from the common. And he’s he said, I love. And it’s it’s very unlike the elevated plants in the more heroic things all up Commonwealth Avenue, and it’s it’s a refreshing change in Boston.

Speaker And those enduring popularity and his seems unending adoption and by popular culture, movies and plays and operas and Lou Reed albums and everything else, what what is it about Poe and not just Poe’s writing, but it seems to the man equally and very difficult to separate sometimes. What’s going on?

Speaker Why is it generation after generation pose the great American flowering of really, I think, an 18th century creation, which is the Gothic, you know? And what’s his name? Was it Walpole? Forget the guy who says the state was so esteemed and found so peculiar in 18th century England, he had ruins, constructed or rebought ruins and he would see a. Treated and struck by lightning somewhere and put it to the end of an L.A., this was part of a romantic vista, the Gothic replace the more French orderly idea of nature, flower beds arranged in marvelous geometrical patterns.

Speaker Poe is the American practitioner of the Gothic and the Gothic. You know, the Vogue currently, you know, in our century now, our decade, vampires and zombies, they’re part of the Gothic. And Poe is the American practitioner of the Gothic and. It has a lasting appeal, though it does in two seconds, you look at it from another angle, like every other view or manner or style, it can be looked at from another angle where it looks like you bought that the seasonal Halloween department of the supermarket, didn’t you?

Speaker And is that something to do with death and fascination with death and the inevitability of death, is that does he connect to that somehow in a way that other writers don’t?

Speaker The Gothic in the 18th century and Poe is the Gothic revivalist of the United States. Like the turn of rock and roll sometime in the 70s into something dark and tormented after being something that has to do with sexual pleasure and being a teenager, all of these have a kind of counter religious origin. That in the 18th century, religious certainty was being supplanted by rationalism, Gothic as a great refuge from both from that contention between blind faith in the one hand and reason on the other hand. The Gothic gets the feeling without having to be involved with the doctrine and our country famous for religious revivals and a certain kind of Protestantism that swells up with a lot of intensity and then becomes discouraged. Poe’s version of the Gothic is a great refuge from that rhythm to.

Speaker This is extremely bargain-basement intellectual history, I’m engaging here, I think we’ve done enough for television that’s just about right now.

Speaker I don’t I don’t mean to get down and talk television, but, you know, we do work at a certain level and this is actually really good.

Speaker So you didn’t ever actually answer on your forum how corny or great or post poetry? I guess that’s the question, Cornier.

Speaker Yes. Yeah, well, I. That’s right. Could you say the whole thing, since we won’t hear my question? It’s an endlessly interesting question to ask how much and what ways is DPO, Corney? And great, some would say, corny and or great.