Speaker I think they wanted descended knee and housemen wanted to create an academy of theater, a serious school of theater. A theater that you had, a school that you had to make a commitment to four years is a very long time when you’re young and talented. And the people who are not in school are already working and succeeding, apparently. And it’s a there’s a great pull to go out into the world when you’re in your late teens. I think I talked to John about the school before it was a school. He asked me to drive to Wickham, rise with him where he was going to meet with all the faculty, the original faculty, the first group of people. And he asked me then to be a teacher. And. I was. Amazed for two reasons. One, because I hadn’t thought of myself as a teacher. And the other reason was. I thought. It meant that I wasn’t an important enough actress and therefore I would have all this time to teach Miss Understanding. One of the most important things both Michelle and John felt, which was to have performing artists be on the faculty. People who were at work in the theater, not people who had retired, let’s say, from the theater, who had taught at many other places. He wanted the students to be around people who were of theater. And as it turned out, I worked more consistently without ever missing school than I ever had before in my life. From the moment I told John I’d be a teacher in that school.

Speaker And in making that connection later in life, what what do you think it was? It was inspiring.

Speaker Well, I think that I was at the right time of my life, the way I look and the way I act, that it would have happened anyway, but that it happened. And I didn’t have to give up school or give up acting. I was able to do both. Looking back seems miraculous to me, but it always worked.

Speaker And having never taught acting before. How did you how did you approach it initially? How did you how did you sort of.

Speaker Well, I had been well taught.

Speaker I had gone to the neighborhood playhouse and I had been taught by truly magnificent teachers. My major acting teacher was Sanford Meisner, who was one of the finest to acting teachers, I guess, who ever lived, I think. And the head of the dance department was Martha Graham. And although it was only a two year course, it was quite rigorous and the classes were small. And a lot of attention was paid to each and every one of us. And. It was. That training, plus my experience as an actress that prepared me to be a teacher. I think I have great reverence for teachers. So to be asked to be one. A kind of a wonderful shock. And nothing has ever given me greater pleasure than doing it.

Speaker Well, with John and Michelle, we’re forming this school in 1968. It was a tumultuous time, to say the least.

Speaker In New York, in America and in young people’s lives. Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker I mean. Prevent from sort of a stab at a sort of a twofold sort of standpoint of being. What what world was? I mean, do we limit it to the theater world? Was Juilliard coming into what was a theater world like in New York at that time?

Speaker Well, it’s so strange. The the the world of acting, let’s say, because I don’t always want to say theater. And I’ll explain why the world of acting. Contained an awful lot of television. And one of the ways I got to know my students in the very first two or three classes would be to ask them informally what? They admired and what they loved to see. And, of course, I learned very quickly that most of it was television. Most of my students weren’t didn’t live in big cities. They came from all over the country and they didn’t go to the theater on a regular basis. And the people they admired were people they could see on television. And of course, I got used to the idea, but it so amazed me because my falling in love with the theater was falling in love with theater. I mean, that was it. It had nothing to do with a piece of film. It had to do with life and.

Speaker But also interested me that their ambitions were not necessarily to be on Broadway. I was born and grew up in New York and the New York theater was my theater because I lived here. My students had to come sometimes all the way across the country to get to New York. And they just wanted to learn acting. They didn’t want to be Broadway stars. And that was so healthy because a lot of them went and did regional theater after Juilliard. And a lot of the original class, of course, were in the acting company, which was the greatest school of all, I think, for them.

Speaker So when you first began teaching, what was the environment?

Speaker What was the building? What were the classes?

Speaker We started the school before the building and Lincoln Center was ready. So we were way, way uptown on the Riverside Drive. And it was all quite makeshift. It was as if we were having classes in huge old living rooms and. And what might have been Ballroom’s. And it was very unstructured. The building was unstructured. And looking back to that building, I think it was lucky because Juilliard, the actual building is so structured.

Speaker And until you get to know it and love it, it seems a very impersonal place. It seems almost like an office after a while. It doesn’t. But in the beginning it does. The cloud, the atmosphere, the feeling was all of adventure. It was the beginning of a school. The good fortune of being there in its first year with only one class to teach. I think there were almost as many members of the faculty as there were students. You got to know everybody so well. And it was all the faculty meetings were thrilling because we were students, too.

Speaker We were learning how to be a faculty together. And I think we succeeded. It was marvelous for me because I truly admired everyone and came to love them too, of course, and learned from them. And I didn’t feel shy about asking them about things. And I was surprised and delighted. To find that the way I taught was what they wanted and that I didn’t have to adjust in any way. There were no rules. I think basically the teaching of acting shouldn’t have rules. I think it’s what is happening in the room, the classroom or the theater. If you’re lucky between you and your students, you don’t have to read any books. And if you’ve spent I was 40 when I started teaching and I’d spent all my life from the time I was 16 on in the theater. I think I was ready. And I think I understood how to deal with the teaching of acting without a list of rules.

Speaker And for a lot of the first year, students, group one class have talked about. Something’s beginning and something’s getting thrown out. Mixed messages. Figuring out together some kind of lovely, tumultuous way, but also in a confusing way. And how did you do? I didn’t know that one is this sort of blusterous group of very old people. It must have been quite interesting. What were some of the things that sort of developed and then went away?

Speaker Well, it was these meetings with the faculty were almost like classes because we would discuss with each other where we were going, what we were doing. And I literally ask each other each other’s opinions. And I I should have also said that before I started, I went to every class I visited.

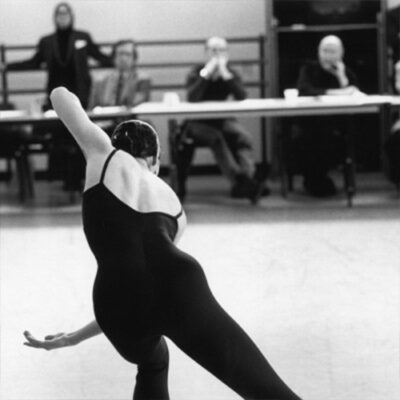

Speaker As one says, I audited a lot of classes before I actually started to teach speech class, a dance class, the movement class and sorry, a Santini’s class, which was extremely personal and individual.

Speaker Her exercises, which weren’t continued actually when she stopped teaching. No one picked them up and did them, but they were exercises that used one word or one gesture, sensitized the actor to one moment. Very.

Speaker Very. UN dramatic.

Speaker Very much to do with behavior. Very much to do with focus. And I think they were. And imagination. The individual actors imagination. And although they were done in class. My memory of sorry is class. The classes that I went to. Were of serious and any and the student. The concentration was so complete between just the two people. And they were they were marvelous. But it was something only she could teach. And I remember I had forgotten that. I remember that I think once she couldn’t be at school and they asked me to take a class a few times and I did. And I loved doing it. But it didn’t come from my own. No feelings about acting. I work mostly from a script, from the play, from words and. Therefore, to be in a faculty where there were great teachers of improvisation and movement. If you think of Michael Kahn, for instance, as their first teacher in just the basic. Relationships of acting and actors one to another, and PLF ever teaching them how to work with masks. And not using texts at all and allowing me, even with the youngest, the newest students to to work with words was wonderful because that’s what I know how to do.

Speaker What were we shown in Syria like? It had an interesting background, of course. What did you know about them before?

Speaker I had seen Michelle Denise excuse me, I’d seen Michelle Santini’s production of Oedipus Rex with Laurence Olivier when it came to America in the late 40s. I saw it three times. It was.

Speaker It was.

Speaker A landmark for me. What theater could be, what great, great theater could be. So his name was Magic. To me, this was the man who directed that play. I also knew him as the first of him, as the first husband of Peggy Ashcroft, who was an actress I admired. Enormously. And I knew he had had a school in Strasbourg. I knew these things. I knew nothing about Syria till I met her. And I was very much in awe of her. So you can imagine my surprise when they told me in a faculty meeting that Michelle Santoni would be doing a reading, a class that would end up in a complete reading of Oedipus Rex, the William Butler Yates translation, and that I would be with the men and that I would be doing the Trojan women with the women at exactly the same time. In other words, that I would be teaching the other half of Michelle’s class.

Speaker I couldn’t get over it. I.

Speaker It couldn’t be possible. Well, it was possible and because we were way uptown sometime sorry.

Speaker Michelle and I would go downtown in a taxi. And I would sit between them.

Speaker It’s as if I were a movie fan and the two greatest stars in the world were in the taxi. And when I realized that we could talk easily because the subject was these students and our work all the OR went away and it was replaced by love. They were they were extremely dear people.

Speaker And what was what was John’s relationship with? I mean, how did this sort of powers that be Abe Lincoln Center even conceive of this school? That would be, you know, John Houseman, sort of man of American theater.

Speaker And Michelle said, I don’t know the answer.

Speaker I having been there once you got there together. How did their. Their work plan, really?

Speaker Oh, they were absolutely a team. Absolutely a team. And and John had enormous reverence for Michelle as a teacher. And his book on style. I told you that I didn’t think you needed books. But of course, there are amazing books about acting and theater. And Michelle Sand in his book about style is is. A great book. And that was certainly referred to very often and. And the Strasberg school and the school he had in London were were very much referred to in piano. Ever had been with him. And so on. So that there was a shared knowledge. And of course, John Houseman, whose work in America is absolutely memorable and seminal, really began his life in Europe. And he was when he was with Michelle, it was like to Europeans.

Speaker So they brought that culture to this school, too, which was marvelous. And. Michelle wasn’t always at school, and then as he got older and ill, finally, he was never at school. And John carried it on. And although I would imagine that the students there today. Don’t know how much and portents. Michelle Sandin, they had in their training. It’s still there somewhere. The.

Speaker The appreciation of technique, the ability to speak well and move well, to use masks, to have discipline, to adore the playwright that’s still there. That will never go.

Speaker And what was John like as a person, you, of course, adoring, you know? And he’s such a figure, it’s hard to even find a photo of him that doesn’t look, you know, extremely dramatic. What it he to me.

Speaker He was. Like a great actor.

Speaker It’s funny that he began to do quite a lot of acting at the end of his life. He was like a great actor, acting the part of a producer, which indeed he had been. And he produced the drama department. He produced it. And we were all part of it. And. It was exciting. Always.

Speaker And even he allowed you to disagree with him, to quarrel with him about artistic opinions or disagreements. And.

Speaker He.

Speaker He was the center of the universe of the drama division. There’s no question about it. Everything went through his office. And he was.

Speaker I knew him first as a young actress auditioning for him when I was, I think, 17. I was now 40. And I’d known him all through those years from that first audition. And he’d become a friend and he’d become.

Speaker People use the word mentor. He was not a mentor to me, but he was a because of his past, his amazing past. If he’d done nothing else, if he’d never done Juilliard, he was still a force in the American theater. His whole relationship with the Mercury Theater is enormous. His whole history in Hollywood is enormous. And then somehow at the third act of his life, to have Juilliard to recreate everything he loved a group of people all working for the same reason and and allowing each person to express what was strongest invest in them made him an ideal head of a school.

Speaker And whoever made it possible, I bless even if I’d had nothing to do with it, because the people who have come out of that school have enriched the American theater.

Speaker Almost without exception, and there’s still to come.

Speaker It’s it’s interesting because you talk a lot about. When people talk about you, is, shall we say, as.

Speaker This sort of, you know, very nurturing and and peer as well.

Speaker People whose style working with people is kind of kindness and warmth. And yet you must’ve witnessed in some ways these terrible struggles that people would have when they were there. It seems that people talk about it from the past, and I see it in the present because it’s a very, very flaying process. Those those first two years I mean, how how did you balance your own style of working with people? I mean, and perhaps, you know, how do you perceive your your style? I’ve only heard how it is perceived on the other end of it. And how did you balance it with this sort of terrible struggle of going through?

Speaker I think. It was a very good choice on John’s part to choose me because. I had been through exactly what the students were going through. I had wanted to be an actress, gone to an acting school, became an actress. By the time I became a teacher, I had a child. My child was growing up. And during my course of 22 years at Juilliard became the age of my own students so that everything.

Speaker I did and do still. Comes from what I am, and I can’t work or can’t create anything of value if I’m frightened or if I’m questioned in a way that. Mix that makes me panic. Or if I feel. That I’m wasting someone else’s time. Now, there are great teachers and great directors who do all those three things, who intimidate even. Confident professional actors to such an extent that they can barely work and out of that situation. Sometimes amazing things come. I. Don’t like that. I don’t like it in life and I don’t like it in work. I do think that the theater is elitist, that the director and the playwright have the right to dictate what they want and should do so. And that discipline is one of the most important things for anyone in any of the arts. But cruelty. Even. A kind of mental cruelty, kind of putting people down, especially at the age they are when they’re students, is irresponsible and. In my opinion, unforgivable. I say this to you now in hindsight, but I know. That that’s what made me deal with his students the way I did when John asked me if I would teach. I remember thinking when I decided, yes, I’ll just go there and teach and then I’ll go home. I could not get them out of my mind. I loved them all. I know. I loved the person in the most difficulty as much as I love the person whose talent was thrilling me in that class. I loved to watch the person who could barely get up and do a scene. Struggle to stay in the chair because he or she wanted so much to get up and do a scene. I think of everything that happens in a school as the process. And you’ve got to be helped. And it’s my instinct to help people.

Speaker And if you sometimes find.

Speaker Sort of a conflicted or did you see the students being pulled apart or did they just end up coming to your class and that was the refuge?

Speaker No, I think to be an acting student is.

Speaker To place yourself for whatever amount of time you’re going to be a student and if it’s for years to place yourself in the position, particularly in the first two years in which almost everything you hear.

Speaker Is not praise, it’s. It’s an attempt by the faculty to help you. But. It can seem.

Speaker Just like arrows of negativism just coming at you. Day after day. And no one teacher knows what you’ve just gone through in a class before you’ve come to that teacher’s class. What kind of a day you’ve had, what your life is like. You’re in the middle of your teens, late teens, maybe early 20s. But by that time, you’re stronger. You’ve probably come to a new city. You’re probably rooming with someone you never knew before. You probably don’t have enough money. You maybe don’t even have the right food and clothes.

Speaker And all this time, we on the faculty. Are focusing on this secret, mysterious, wonderful thing, which is your talent, which you don’t even know much about.

Speaker And you you’ve never been in a room with only other actors before, you’ve been in high school and you’ve been wherever you are. I’ve done amateur theater now. Everyone.

Speaker Has the same goal. How confident can you be and how confident can you be every day? I think an actor’s confidence, just like a child’s confidence, if you’re a parent, needs to be dealt with and nurtured. And. Aided as much as his talent. And I think that’s my instinct. And for me, the results were. Absolutely remarkable. I saw things. In my class that. Nothing could have prepared me for these leaps of growth of as. As young acting students and I could look around the room and I saw that it was for everyone. We didn’t sit. I didn’t let my students critique each other or judge each other. I don’t like that either. I know that is also a technique of teaching, but I don’t like it. But I would look at the other students while people were working and see this. The thrill of recognizing what can happen. And that taught them to they taught each other.

Speaker And they were good to each other. And I usually had the incoming group altogether in their first project and.

Speaker I think more than anything else, what I tried to do in addition to getting the play done in a very short time was to give them a sense of the group they were in and their dependence on each other. Because that will give them power, that will give them confidence. If they’re all. Wanting to succeed together, wanting to work together. That’s when the great work is done.

Speaker Do you think that.

Speaker That that was part of the development of the group philosophy that you would stay within your group was to in some way create a company. Do you find that helpful or do you think.

Speaker Yes. Because here it was difficult to say.

Speaker Have you noticed noticing that a little cleaner every time you pull up, your hand was clenched? I never saw it.

Speaker I think that. I think that John and Michelle.

Speaker Wanted each class to have the possibility of being a small acting company. And what you want in a way and never have time to say at the auditions is two to each person who comes in. We are building a small company of actors. And there may be someone so much like you. That you may not be chosen. In other words. You want to build through the four years. A group of students who can do many plays together as a as the cast of a play. So you don’t want it. Let’s just say for a foolish you don’t want four. Absolutely. Handsome, virile, dark haired, blue eyed, muscled man in the same class you would like. One would be very happy with one. And then you would love to have someone who could do character work. And you will. So that.

Speaker Yes. Each class was a little company in itself, but friendships, of course, and social life developed between all the classes. But but you were definitely you were definitely that class. That group.

Speaker We were talking a little bit about some of these these tumultuous times in New York and all of these students coming in. I mean, now it seems less difficult to maybe give yourself over to this insular world. In 1968, 70, I mean. And I’m wondering, you know, even though of the Columbia you know, the Vietnam protest.

Speaker Were you aware of the using the Kent State line? Tell me about it. I mean, just also not even political. His name is inability for the for the kids to have another life. I think if you.

Speaker Are going to give your life to the theater. You have to make a sort of terrible bargain and you have to say, I mean, if you’re young, I’m going to miss a lot of other things. And if it’s worth it, I won’t mind. But the political life in America in the late 60s and early 70s simply crowded in on the students and those who who had interests in life outside the classroom were terribly torn and. I thought it was good. I thought. They should know and they should care and they should discuss it. And that will make the work even. Absolutely. It’s a funny word. Holier I. By that, I meant more separate, more special, more focused on something apart from real life. But since this special thing is based on real life, why not allow as much as you can from the outside to come in? It takes away the ego and the selfishness that sometimes happens to young actors. I didn’t feel it very much at Juilliard. I really I felt they were selfless. Most of them, it was for the work for each other. But of course, when the Kent State shooting came and and there’s something else I don’t really know if it’s my place to mention that the fact that drugs did exist and some of the students did use them. And I was too naive to realize it. I thought they. One or two of them were just not doing good work. I had to be taken to the office and have it explained to me that they were rather out of it at the present. I had a lot to learn, too. I had a lot to learn about that age, and I felt enormous compassion for it. It is very, very hard. And I’m sure if we were speaking of another profession, medicine, you know what those young doctors go through? We say how hard and how tumultuous it is. Well, yes, the study of anything, if you want to be an expert, it’s going to tear you apart when you’re young and part of your. Youth and early adulthood is going to be spent putting together what you’ve learned with how you live. And as we’ve seen in all the years since these graduates have been working in the theater, almost everyone is able to do that. And in a remarkable way there isn’t. A Juilliard student, there are just a lot of very talented people who have been to Juilliard who have learned how to use themselves fully and express themselves fully and have the technique to do it so that their acting is. Memorable. A lot of wonderful actors and wonderful performances in all the fields where you can act. But it’s the things you remember. That last in your memory is an audience that matter. And I think. I’ve seen my own students and certainly students who’ve graduated long after I was no longer teaching there whose work I’ll never forget. That’s the greatest compliment I can give them.

Speaker Going back ever so briefly, what what did happen in response to. I mean, what did the students do, not just feeling, but were there actually organized responses to the state or.

Speaker Yes, there was that amazing day when they put white clown white all over their faces and simply lay down as a protest in the beautiful around the fountain. And Lincoln Center, the whole.

Speaker A whole world seemed to be protesting at that time and for them not to. That wouldn’t have been right and their way of protesting was. So dramatic, I mean, they looked young and they looked dead. They were just lying there like corpses still for the longest time. I’ll never forget it. It was something they wanted to do and they wanted to do it during school. And and school hours are very rigid, very. But this was larger. This was. Something I had to do, and it did.

Speaker Did other faculty I mean, I remember reading it in John’s book that he said he also laid down at some point.

Speaker Oh, yes. You know. The students must have thought of John as sort of a father figure older, but one of the things that was marvelous about him was that he was an extremely curious man. Full of curiosity, full of questions. And he never forgot his youth and his protests and his political feelings. And so I think. I think that there was a whole part of him that would have said take the whole day, take a week, take a year, but you can’t run a school and and not run a school.

Speaker So he could just he wanted them to know he was with them. And I think all of us did. And I think whenever anything happened.

Speaker That affected one’s own class.

Speaker A group of students you were working with at that time. I think it was terribly important for them to know that you weren’t separate from them. My students, for instance, I never had anyone called me NLD at Juilliard. I don’t anywhere. But I mean, of course, I was Marian. And of course, they were who they were.

Speaker And the hardest thing for me in the beginning was to learn their names quickly. And to give them the honor of calling them by name quickly. I used to wrench my brain as I looked at them in the auditions and try to remember who they were so that they would know. I knew. They need that identity and they need to know you’re with them and it isn’t just in the school room.

Speaker I think.

Speaker Did you therefore become someone that people were always coming to their love was no.

Speaker No. Oddly enough, no. I think I was able to do. This. Meeting of feeling with my students through the work. I didn’t take them out to lunch. I didn’t have them come to see me at home because I thought if you do that, you’re going to hurt someone else. There’s always going to be someone who thinks, oh, you’ve had lunch or whatever, coffee or. So I would strike. I would excuse me. I would try to stay at school a little longer. Come a little earlier or speak to them after I saw them do a play from another class, you know, from another director. Be available to them in the school. I didn’t want to cross the line.

Speaker Of having a favorite. Because that’s not right.

Speaker They will. They all talk about your endearments. Oh, how would you put it? They don’t get that. Let’s re-enact it all. Well, you know, in checkoff.

Speaker Sometimes he’ll have a character call another character. My little bird. I was so in love with Checa from the time I could read him, I suppose I started reading him when I was 12 or 13. I picked it up somewhere and. The word bird is so lovely and it’s an endearment, and I use that word with my own friends, too. I don’t know why, but I did at Juilliard. I didn’t hear myself do it. But I realized, you know, they can take you off. They can. They can. My students can do me better than I can do me. And some of them are absolutely brilliant. You should hear Robin Williams do me, but. And I call them darling and I call them dear. And I didn’t stop. Even when I knew I was funny because they were my darlings and my ideas and my birds. And it didn’t bother me. And I don’t think really it bothered them. I. I felt comfortable with him. I truly. They came into my life, these hundreds of young people that otherwise I would have completely missed. To be a teacher in a school like that is a great privilege. It would be I would be different. I would be a different person and my work as an actor would be different. And. The fact that it was simply taken for granted that I would direct Chekhov and Shakespeare in this school when I had never directed before and I directed all the time in that school. Taught me everything.

Speaker Were there just wonderful performances that I mean things I mean, I know if we can emulate leafing through these programs, we know that interactive. We were there were there programs, shows that you directed, the performances from actors that you remember that are just vivid in your mind?

Speaker I I really mean this, honestly. Not one stands out more than another because. It was sometimes.

Speaker I would see exactly what I dreamed of in the first year later at the end of the second year. I think I knew I knew you could do that.

Speaker And then the other pleasure was, I would never have known. Never have known. How far you, another actor or actress, could grow in that time? I.

Speaker And looking back, I think how few hours there really were to direct them. The rehearsals were always in the afternoon after they’d worked all day in class. And stayed up all night preparing for class the next day and still you you saw things you’d never, never forget. And when I go to the theater or movies and see.

Speaker These actors now is sort of the height of their power, I think. But I knew it. You showed me. I knew it. It’s just a question of growing into your talent.

Speaker You could read me the cast list or I could read it to you and I could tell you about every actor and what they did. And when I see them now a lot.

Speaker On Broadway and off Broadway. I have flashes of the room we were in in three or four or three or six or three or one where I taught them, and and then there are people in my classes that were not did not complete the entire four years.

Speaker And I thought it was lucky, too, that I’d only studied for two years because I could say to them.

Speaker You’ve already had more than I had. You’ve already had enough to go on. Don’t be sad. Don’t let this be a negative thing. Go with what you have. And end and a great many of them have succeeded to.

Speaker We’ve talked to a lot of the and this is not something necessarily that you can speak to, but we’ve talked to quite a few of the African-American actors who struggled, really struggled in their roof and even struggle perhaps more as the philosophies and the head of the program changed from John.

Speaker Housebreak my mom. Yes. Things were different. Yes. Were you always aware as a faculty member of those struggles? Was the faculty thinking, you know, often people are thinking much more about something they think they are?

Speaker I felt.

Speaker So grateful that we had black students. I thought it was so important.

Speaker And if something goes wrong here, he had a.

Speaker Should I say African-American? I’ve never used that term. I don’t know.

Speaker OK. No, I always do. OK. Hopefully.

Speaker Oh, I thought.

Speaker It was so important to have a mix of students in the way they looked, in the way they talked, in what parts of the country they came from. And certainly in the color of their skin. And I felt I hope this is the right word, humbled that I would have the chance to work with them because.

Speaker In my school. In my acting school, until my class demanded that there be black students. There were none. That’s just in the late 40s. So here.

Speaker We auditioned everyone, and these wonderful talents came. And God knows, if they had enough money to make the trip to New York to do the audition. I don’t know. But it was always a minority. Still is.

Speaker I had never.

Speaker Never heard one black student complain of his or her treatment at Juilliard. That does not mean they were happy all the time. And it does not mean that this that until we began doing black plays that there were no black plays. We had to learn to. We had to grow to. And we had to get more black students. And I hope we will continue to. Until you don’t see the difference.

Speaker But.

Speaker I am being so careful not to single people out, but the other black students I taught were wonderful and they had. Sometimes much more of a struggle in the voice and speech department.

Speaker Because they were brought up speaking what is almost a different language and why not? That’s where they were brought up. That’s how their mothers and fathers talk to them. And the teaching of speech is so.

Speaker Connected.

Speaker With the entire well, all acting is really but in speech, the entire process of growing up and how you form words and how you first heard words that to change it.

Speaker It’s it’s almost the most difficult craft in the school. The most difficult task.

Speaker And. I just.

Speaker Perhaps things happened that I didn’t know about, but I know no one ever gave up. No student ever said, well, I’m not going to be able to do that in or I don’t want to do that. They used Juilliard. And that’s what you should do with a school. Use it. Take what you can. Take what you want. And I always used to say in my class, I’m going to talk to you as if I know what I’m saying. But if you don’t think I know, you don’t use it. If it isn’t what you can use, don’t try to use it, because I’m in a sense telling you I’m just offering it to you. But you can’t do that in speech and voice. You really have to do it. The way the teacher teaches you, there’s such freedom in being an acting teacher. It’s it’s so releasing and, um, but until you’ve got your tongue and your teeth and your throat and everything working the way you want, it’s it seems almost constricting. And at the same time that the teachers are saying, don’t criticize yourself, don’t hold back, be free, do it. Well, at the same time, you’ve got to do this to. Now, that’s so easy for me to say it, but this is a tremendous dilemma for a young actor. And day after day, not being able to solve it. One thing to talk about it, but to do it, it’s so difficult.

Speaker And. At the same time. That everything you.

Speaker Make available to a young actor or teach young actor has to be based on that individual. At the same time. We are saying to that individual subliminally change.

Speaker Change. Well, who are we to tell people to change? We have to be very careful. Change how?

Speaker Not in that secret part of your soul that makes you a talented actor. Just in a way so that you can exist in the theater more fully.

Speaker So that you will be more prepared and have a greater life after school.

Speaker That’s what we owe them.

Speaker Well, it’s very I mean. In a way, Juilliard was this sort of unique mix, if I think about somebody, particularly actually Stephen Henderson, who is in Group one, who I’m sure you know who I interviewed in California, we’ve actually Amy and I just went Sarbjit.

Speaker What a performer. And he he talked a lot. Well, he had sort of more political struggles, but he said yes.

Speaker He had a lot of money. He also went on to study with an adviser. And the combination, he said, in a way of that technique. And then this other more more real work.

Speaker Where exactly was an incredible combination. Absolutely. Eric Lascelle. Absolutely.

Speaker Who was cut dramatically, went to NYU. Some people need the combination. But do you think that Juilliard in some ways was unique? Was unique in what it was. Was it bringing a kind of a reality to a classical training? Was it combining something in a way that hadn’t been done before? What if we could somehow place what was unique about what was happening or made it grow in the way it did?

Speaker I think what made it more than just the kind of academy I mentioned before are the kind of college of acting or whatever you want to call it. What made it? More creative and can continues to make it creative. Is that in addition to the attention to technique? I believe there was just as much attention to. What comes through the students nature through what is human? Most human about the student? And when that gets lost, then the school isn’t as good. And if there happened to be, let’s just say, guest directors who are not interested in that humanity, then they’ll be a stretch. That is rather dry and rather empty. But there will be times like that after they graduate so that it is not lost time. It isn’t creative in the way we want it to be at school. But even the faculty in meetings we would discuss that was not a good choice of a director. It’s hard. You know, we weren’t wanted always to bring in different directors because that’s what you’re going to have outside of school. You don’t want to be directed by the same people year after year after year. Juilliard, I think. I think this about the dance division to come Combine’s. The rigidity of formal training with the possibility of such enormous self-expression that the individual artist who leaves certainly the drama division after four years is prepared for almost anything. Any kind of theater. Any kind of work and can adapt to almost any kind of direction or attitude. Because. The actor is, in a sense, the servant of the text. Definitely the director. The situation where you are working, what what is available, this what theater you’re going to be in and an actor must adapt to all those things. You can’t go through your life fighting those things. You can make choices as you get older. And we hope at Juilliard that we’ve given them the strength to make choices. I don’t want to do that. That’s not the way I want to work. Or let me try. Let me see. How I can adapt what I’ve learned to what you the outside world wants me to do. And I think in general, we provide. A wonderful, strong background for all kinds of work, but all acting is based on truth. And the minute people accuse Juilliard of being Alstyle, I smile. I have to laugh. There is no you can’t act style. You can only act a real person. In a situation unlike the one we live in today. So why not learn how those people did behave? Bring that behavior to a human being, put them in the place, the playwright put them. And you’re free as a bird. You’ve got to learn first.

Speaker Well, there is that criticism about style and that criticism about voice or whatever people call the Juilliard isms and do. What do you think that that comes from just from Andy?

Speaker I don’t. I don’t know. There are people who will.

Speaker There are people who feel that you cannot teach any art, that the artist has an inborn talent and develops that talent and uses it. Certainly true in painting and sculpture. And many, many art forms I have never felt. I was a teacher of acting. I thought I made a place for students where they could learn acting by acting. I don’t think Juilliard sends out a certain kind of actor. I don’t accept the criticism that they’re all style or that it’s all speech. I think that because they can and do speak well when it is needed on the stage or screen. I think some people might even resent it, because in the America we live in now, we don’t want there to be an elite. We want everyone to be the same. But everyone isn’t the same. And the theater is an elitist art. And if you can’t project your voice and they don’t hear you, you don’t belong in the theater. And if you can’t make a transformation. Of yourself into someone that the audience will believe is someone other than you. That’s not good enough then. Might be good enough for a couple of years or a couple of movies. But. We are thinking at Juilliard about a life.

Speaker As an actor or actress. And you.

Speaker You’ll just have a more wonderful life if you know what you’re doing.

Speaker I I think many, many actors like that also its ability to do it. Let it go. Of course I will use it. I won’t use it.

Speaker Of course, when he can and he can do anything. He can do anything, any kind of character, any kind of a Juilliard graduate should be able to do.

Speaker To the best of his ability, any kind of character from someone who can barely pronounce his own name to Moliere. You just should be able to.

Speaker We talked about a lot of people that, of course, did very well. Either, you know, winning Oscars, but to those two wonderful lives in the theater, that maybe I’m not a household name, but it’s.

Speaker Well, you know, a happy theatre career. Were there lots of people that.

Speaker That you still struggle and struggle. And just make no headway, did you. Did he remain in? And what is that? Is that is that just luck? Talent and ambition. People that were there, are there a lot of people that you saw no longer have a like a theatre?

Speaker I still know some students I loved who are not. Acting. Full time, let’s say, who who have who have not been able to devote their lives fully to the theater. But in most cases, it’s because of family. It’s because of husband and children and so on. And I don’t feel that they feel regrets. There’s also a great difference in kind of.

Speaker Of actor or actress? Some people are not looking for fame and are not looking for recognition. And the fact that they don’t get it is not a terrible disappointment. If you want to be famous, if you want to be what used to be called a star, it must be very disappointing not to be one.

Speaker I. I don’t think it matters if your name is known, of course, because I think the memory of what you’ve done is what’s important. It may be because that’s not been my life.

Speaker I certainly was drawn into the theater by people whose names everyone knew. I wasn’t ever able to accomplish that. And so I’ve never thought about it. It’s just not.

Speaker It doesn’t occur to me.

Speaker My name. Or my students names. In front of the public, it’s the work. I just really feel that I’d be a different person, otherwise I’d be frantic. I think where’s my name?

Speaker I don’t care.

Speaker I never I never thought that the theater was a place to get rich or be famous.

Speaker And I have, I think. A little bit of contempt for people who do. It’s none of my business. But.

Speaker You have to have your own life. I think it really applies to everybody. You must’ve been so aware of the other people on the other faculty, the other music of the day.

Speaker I loved the fact that there were so many schools within the school building. And I had the great good fortune of working with Martha Hill and the dance division and of working with Doris Humphrey. And of working with Virgil Thompson on this Lord Byron operand. Of working with Barbara Hendrix on her acting in the Alice songs that she did. And that sort of interaction in the school thrilled me. And I like many actors or actresses more. I guess I wanted to be a dancer when I was young. And being in this school where the School of American Ballet, where I studied dance existed also. I mean, Antony Tudor, for instance, the great English choreographer, was like a god to me. And to go up in the elevator and chat was I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe it. The atmosphere was so wonderful to walk past an open door on the third floor and hear music that was so rich and full that you had to stop and realize that Leonard Bernstein was conducting a conducting class, things like that, and realizing that your students were this was available to them. Walking through this building, all these wonderful things, that that was marvelous. And I’ll tell you something very personal, which was I envied my own students. I thought, oh, if I could have had this, if only I could have had this.

Speaker I always feel like that.

Speaker Back to you in your sleep at night, sometimes you have those dreams where you’ve gone back to school when you’re older or you’re not usually for anxiety.

Speaker You had study or something. But see, I’ve been back there all year. You’re not really a student, but I’m not a teacher. But I’m not. But you’re there. I think I feel like I have a terrible withdrawal.

Speaker You will. I mean, I’m sure this has been an amazing experience for you. And I would have loved to have been with you all the time because I think about it a lot and I think about how fortunate I was and how fortunate the students are and were.

Speaker Why did you decide to retire and not remain?

Speaker What I fell in love with Ghassan Kanon, and I realized that the hours I was teaching were the hours I could be with him and that that was the third act of my life. And I, I, I taught for, I think two more years after I began to be with him.

Speaker But then I thought, I can’t. I have to choose. I missed it. I missed it very, very much.

Speaker I thought I’d be a teacher every day as long as I live to be an old lady.

Speaker Teacher.

Speaker And was it hard for you with the. Healthy.

Speaker Very. I missed John Houseman enormously.

Speaker And it’s funny because I thought Michael Kahn would be good to come, but it wasn’t the right time.

Speaker And now he is there and it’s thrilling.

Speaker John was like a half a great sun shining and an end.

Speaker And because I have known him ever since I was a young actress, everything about the school and John seemed marvelous to me.

Speaker It was never quite the same for me after that. I don’t mean the teaching. The teaching got more and more wonderful, but. The faculty meetings with John and his way and his wonderful the way he spoke and just looking at him and he just. He was an intrinsic human being.

Speaker And.

Speaker When he left, I missed him very much like a spoiled child. I wanted him.

Speaker And what I mean, there had been and Michael spoke with some degree, a lot of know politics and that he wasn’t happy when he left. I mean, that must have been also difficult to move on with somebody else. But did the philosophies changed? Interesting things happen in other people’s.

Speaker After Jon left. I didn’t feel. As much a part of the faculty, I was still. And of course, I went to all the meetings, but it wasn’t quite the same.

Speaker It was more like a real faculty and less like a group of artists who got together to find out what they were going to do and to discuss what was happening. And it was it was just different.

Speaker And I began to.

Speaker To sort of stay on the third floor where the classrooms were much, much more.

Speaker I don’t know why, but I haven’t thought of it till this moment. But he.

Speaker He was wonderful. And I think Michael is wonderful.

Speaker And Michael Kahn helped me be a teacher. His confidence in me and his allowing me to come. I used to go to many, many rehearsals. I used to go to as many rehearsals of other teachers plays as I could.

Speaker And.

Speaker Michael was a tremendous influence on me, too.

Speaker Well, you see from with Moni, that’s a field I know modern dance, having started with Martha. I.

Speaker I know his field more, the movement field, and I think he’s a marvelous teacher. And of course, it’s much more than that. He can do anything. He can direct to, of course. But I didn’t couldn’t go to as many of the movement classes, so I wasn’t as. But I would go to the speech classes, especially if I thought a student was having trouble. And Elizabeth Smith and Bob Williams always let me come to their classes and. And. And the wonderful Edith Skinner. When I was talking about the discipline of speech and so I was thinking very much of Edith was from the old school, as indeed, how could she not be very demanding.

Speaker And a brilliant teacher. And now there are people teaching at Juilliard and probably in other schools that are come from Edith. Of course.

Speaker I think each each head of the school director of the school has brought wonderful things to it. It’s just that.

Speaker John and Michael are like bookends to me now. I think it’s so amazing.

Speaker Well, there’s sort of the first to be they went out of the audition.

Speaker Exactly, exactly.

Speaker And so well, and a Socolow and I used to work with her and her dances and sometimes now. Right, some of her dances. And there again.

Speaker She was almost militant in her demands on the students, and it was thrilling for me to see her make those demands because I can’t I’m just not that kind of person. I mean, maybe I do in my own way. Someone else would have to tell you that. But.

Speaker Because I don’t accept second rate work. But I mean with Anna. It was right there in the room. It was. It was. Amazing. And seeing your students in other people’s classes gave you enormous insight into how you could help them. And a greater understanding of their strengths and weaknesses.

Speaker I imagine. I mean, I’ve I’ve been you know, I go round and round and it’s amazing. And I’ve seen people grow a lot this year, but I’ve seen the third year actor that I. Yes. And this is, of course, the performance here.

Speaker Yes, yes. Yes, yes.

Speaker But, you know, I see them struggle so much with the kind of lack of sort of self loathing, kind of constant battle, constantly upset by casting, not knowing how they. And maybe that’s just the arc of the four years because they all seem to struggle like that. Maybe more dramatic than others, but he’s very dramatic.

Speaker Well, I think it is a struggle. I think that the process of being trained is a struggle and.

Speaker One should not forget how hard it is to be disappointed, not just once, but several times, let’s say in the course of a year that you didn’t get the part you wanted to play. All those things are very hard to struggle with, and all actors are prey to a kind of self. Loathing, I suppose you’d almost call it.

Speaker But. It’s the same.

Speaker In the theater, it is not going to change. You’re not always going to get the part you want. And you’re not always going to think you’re doing well and.

Speaker It’s just it’s something you have to deal with. It’s part of the work of being an actor to deal with your own lack of self-confidence. Need to find a way to become confident without ever being arrogant. It’s it’s a task. I am not a religious person, but I can’t imagine what it takes to be a nun and to give your life to that. What I’m trying to say is I don’t think it’s just the theater.

Speaker I think in any profession where you or life work, where you say this is what I’m going to do, you have to be willing to.

Speaker Being a kind of agony, and you have to be careful not to love that agony. Not to wrap it around yourself and use it. You only the individual can break out of it.

Speaker No one can do it for you, not even if you love them and call them birds and touch them. They’ve got to do it themselves. And most often they do. The survival rate is enormous in Juilliard. Doesn’t make the pain of those who are disappointed any less, but. The strong ones do survive. And part of their strength is their talent. And we have nothing to do with that.

Speaker So it’s very meaningful. But it’s true, isn’t it?

Speaker It is true. And all these things that we’re saying. It’s too early to say them to a student talking about acting isn’t teaching, acting, doing it. You see? Yet you think, oh, God, if I could just sit down and talk. It’s like being in love, you know. Will he never say what I want to hear? And he’ll say it. When it’s time. But you can’t make it happen before it’s time.