Speaker Tell me the about the occasion in which you first met Jerome Robbins.

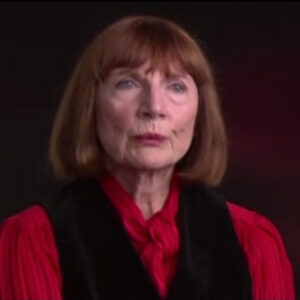

Speaker The occasion when I first met Jerome Robbins, well, I was about eight and a half or nine, I guess, and I was in the Fokine Valley and I had been with Fokine for two or three years by that time, and had done some performances at Lewisohn Stadium with his company. And we were rehearsing at the famous Studio 61 Valley Arts and Carnegie Hall. And two young men arrived and a few days after rehearsals had started and they were just being an addition to Sheherazade. And I found out years later that that was Jerry and a friend. I never knew who the other boy was. They were about probably 16 ish because I think Jerry’s maybe. Uh, five or six years older than I am, and anyway, the next time I heard of him, of course, he was with ballet theater and he was doing fancy free on his own, although first he had done three virgins and a devil with Agnes the Deville. And I still have an image of him going across the stage as the young man twirling arrows. And he was just so sprightly and and gay and jaunty, very jaunty and delightful. And I think from that on, Agnese and he were very good friends. Later she told me that he took her to see Magdaleno when it came to Broadway, the jackhole show, which was really breaking the records for choreography. It was so unusual. And Jerry said, oh, you’ve got to see this like this. He saw it six times a year. So anyway, that’s kind of how I got to know him.

Speaker Did you see him dancing fancy free? Yes, I did.

Speaker Well, Jerry was a fantastic performer. He moved beautifully. He could act. He was witty, exuberant energy and fun and. There was something so honest and true in the way he choreographed those three sailors, the way they walked and just every little thing was so true to life and yet high art.

Speaker What was your impression of him personally?

Speaker Offstage, socially, Jerry was one of the most charming, delightful, warm, funny, witty, great raconteur and. Just utterly charming, wonderful personality and very sociable, and then years later, you had an opportunity to work with him, right?

Speaker And tell me about that. What was your audition like for.

Speaker Well, when we first I auditioned for The King and I.

Speaker And he had already hired Yuriko and Michiko, who were doing Iliza an angel, George, and of course, they were petite and marvelous and adorable. And I was all of five, two and three quarters at that point.

Speaker So even I could look down on both of them. And the few of the girls were five, four. So everybody looked kind of scrunched down, trying to be small because they told us we were going to match up to Yuriko and Michiko. And finally, Jerry said, Oh, come on, ladies, just stand up. You don’t all have to be five feet.

Speaker So he gave a general audition. We didn’t know what we were going to do. And it really wasn’t until we were well into rehearsal and we had had Siamese class every day. We had volunteer class at nine thirty. And if you didn’t come to that warm up, you were in trouble because once signees class started, we got into a deep second and stayed there for hours. And we were stretching all these odd finger exercises, stretching this stretching the thigh while lying on the floor with it and pulling it up. And it was painful for Western bodies.

Speaker But Mejico was a wonderful teacher and. After a while, we all began to look pretty good.

Speaker Oh, let’s go back a little bit and if you can just tell me what the key and I was was based on, tell me a little bit about what it was and what the stories are.

Speaker Well, there was a book called Anna and the King. I think this is Leonowens was her name. She was an English teacher. She went out to Thailand, Siam at that point with her son Youngson, because she was a widow and she was to teach the royal children. And Prince Chulalongkorn, who later became king, played with her son. They were about the same age. And the king himself was looking to westernise the country somewhat and to learn he was very well educated, very thoughtful. He had been a monk and. He really wanted very much to learn everything he could about the West and he read everything he could get his hands on, so she was, I think, surprised Mrs. Leonowens to find out how much he knew about the West and about science and about inventions. And so when Rodgers and Hammerstein started to work on this, I guess Hammerstein worked on it alone until he got the book together. And he wrote a really wonderful book with a very sensitive approach to the king and the court, in spite of the fact that there were certain barbarism still going on. I remember when I did a tour in 1959 for the State Department and we were entertained by the king of Cambodia and people still came into his presence, bent over quite low. They weren’t on their knees all the time, but there was a great deal of obeisance going on as opposed to when Mrs. Owens got there, you know, and they really came in and immediately went down on their knees and their heads to the floor. So there was a lot of that in the play. And and punishment for any infraction was severe and instant. Yeah.

Speaker Did you do any kind of special research for the show?

Speaker Yes, he did a lot of research. And in fact, I went to one pre. A. Well, it was before the show even got auditioned and.

Speaker Uh.

Speaker I think it was mostly Italian, Morra’s things that he was trying out on us, and later I found out actually I found out from Deborah Gelwix book, which I hadn’t known, that he had studied with the Remora and ballet arts for a lot for many years. And I had been a protege of of of Nimura also. We were never in the same class because Nimura wouldn’t let me study with him until I was 14. And by that time, Jerry was off doing all kinds of other exciting things. But it was interesting that. He had had that same training, so when he came to want to do King Simon Legree, I think he suspected that I already had a head start on that, which I did because of Nomura’s work.

Speaker Were you under the impression that he was a person who sort of was winging it or is you a person?

Speaker You said before he did some research or he did a lot of research. He came in with a lot of material.

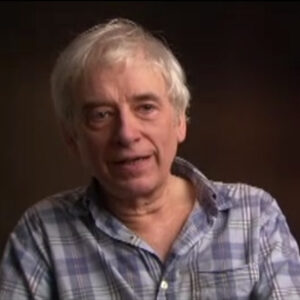

Speaker And then then he would improvise. We’d have to follow him. The difficulty of working for Jerry was that he could get up, come up with five variations of the same phrase within a minute, and you had to just keep up with him. You just barely learned the first one and he’d have changed it already. And then he would look at you with great disgust, which was very demoralizing and. He didn’t usually say anything, but you could tell that he was just say, oh, why am I saddled with these inept dancers? You know, and you just felt awful because we all admired him in spite of the fact that he was could be quite mean something. And he wanted him to like you. Yeah. So there was this constant thing of beginning to get angry and hate him and at the same time say, oh, if only he’d only I could make him happy. And he liked what I was doing.

Speaker So anyway, that’s. What do you mean you can get me.

Speaker Well he would harp away on certain steps with poor people especially and over and over and over again and sometimes not being helpful and sometimes he would be helpful. So you were just working hard, getting more and more frustrated and therefore bad in your dancing.

Speaker The other thing, once he assigned us our parts, as soon as he only did it to me once, but he would have an understudy, you’d be doing your section across the floor or whatever, and he’d say, Oh, Anna, you better come and come along behind her and learn this.

Speaker So you’d have one or two understudies trailing you again, demoralizing. But also it was the fact that it was winter was cold. We were in a dark theater. There was only one work light to work with. This was 1951, so we didn’t have lights on during rehearsals. And so there you were, cold and miserable and the floors weren’t all that clean. And we were always on the floor crawling around. And you’d stagger home that night to wash your tights, have a bath and fall into bed. Saw it up the next morning. There was no mercy. No mercy at all, no sympathy with that in the least, and there were several equity rules that came into effect during the King and I run, I mean, that were because of the king and I that Jerry had made so bad that equity made a rule that you couldn’t have that just rehearsing on marble floors anymore.

Speaker Why would there know Lights Union?

Speaker They would have had to pay for a union man to come in and turn the lights on.

Speaker Of you remember who Mara Solheim was?

Speaker I don’t know anything about her, no.

Speaker Like you said before, that she was involved not only as a dancer, but I think she brought something else to the project Michiko new Siamese technique and repertoire.

Speaker So she not only was a beautiful dancer herself, as you can still see in the film, she’s an angel, George, in the film.

Speaker And but she was a very fine patient, quiet, very quiet, as opposed to some of the other people in the room.

Speaker And so we worked very hard for her and we were happy to because she was always kind. She was always very clear and she was so enchanting to watch. We both she and your ego.

Speaker This is the famous Martha Graham ego. I’m talking about Kiguchi. They were both just fantastic dancers. So we enjoyed looking at them all day long and following them, trying to learn what they were doing.

Speaker OK, Tom disclaims, why did you can I’m just gonna ask you again to show me some of the things that you were working on in rehearsal. You indicated before a little bit with your body, if you can show me some of the things that were special to King and I had to learn.

Speaker Uh, OK.

Speaker Some of the things that were very hard for us as Westerner’s was to to get this hand going straight up and back, which I could do better than this when I was in 1951 or even during the movie. But, you know, so you pushed.

Speaker So you had to be able to do that if you could if you could do it with your hand about the level of your shoulder up here. Yes, that’s right.

Speaker And I can’t go out there, I guess.

Speaker OK, I’m sorry. That’s all right, Tom. Thank you. OK, so we’re going to start.

Speaker One of the hardest things for the arms was to to get this palm flat as if it were against the wall. And even more than that, I mean, I can only get it to there. And it should be going up this way if you had really good Oriental hands. The another gesture was to put these two fingers together like that and these and that was a bird. But what you wanted was to have this. If you put it on the floor, it would be absolutely flat out. As you can see, I can’t even come close to get it flat and things like that. We would do, you know, to show fear. Some of the other and then, of course, I can’t really show you the kneeling one, but if you sit on one heel and put your other leg behind you with an attitude position like that on the floor, that really stretches your thigh muscle and.

Speaker We did a lot of that, so you had to get very comfortable with that.

Speaker Deeply, I had to be very comfortable. Big second position.

Speaker So just tell me again, because I’m not sure I know what you meant, but I was completely clear then. What was the rehearsal day like before you started rehearsal? You did something else.

Speaker We had a volunteer class rehearsals, I think started at ten thirty. And I can’t remember exactly. We had an eight hour day, but full rehearsal day. So after we had class with June Graham, who also was a wonderful dancer, she was the captain. She had been in something else of Jeri’s. So she would give class, but she would give bellbottom almost the second thing.

Speaker And none of us were used to that technique.

Speaker So we finally asked very politely if those of us who are kind of soloists already a little bit, we didn’t know what we were going to do. But anyway, we had the courage to say, do you mind if I warm up on my own? So about four of us did that and. But we still came in at nine thirty in or early, as soon as we could warm up on our own because the actual technique class began exactly on the dot of either Channel Ten thirty and that involved all these unnatural for us stretching and plays and getting and sitting on our heels with our knees on the floor, which is very comfortable and easy for Asian people, but not for western us on the whole, that is. And then we just go through technik full. Um, four hours of the morning, three hours in the afternoon. Without stop and we learned everything, there was no even after we had assigned sections, Jerry had us learning everything, which I’m not against, except that it was very tiring. You never had a chance to sit down and rest.

Speaker Hmm, let’s talk about the show. Tell me what you remember about this little miracle, the march of the Siamese children.

Speaker Uh, well, first of all, they were able in New York to hire the most adorable, agentic children. They were just darling and very smart. And the littlest boy, I think, was five. And he was quite small with a chair. You face just wonderful bright eyes and, you know, a very alive. I think he was probably Chinese or Japanese, I don’t know which. And it was a mixed mixture of some Puerto Rican children, anybody who looked like they could be Siamese and.

Speaker So when they would walk along these these little things, they really looked like this even to us who are short people and. And I think Jerry set all of that, the idea was Oscar Hammerstein, but and.

Speaker Jerry devise a sequence, and he devised all that choreography and he was wonderful working with the children and was different. They each had an identifying quality about them. One was mischievous. One was frightened. One was glad to see your father and therefore did something a little wrong. And it was very clear each child was very carefully worked out like a big acting part.

Speaker It seems like each dance in the show advanced the story in some way. Mm hmm. Could you search, as you were just describing? Could you talk a little bit about getting to know you? Do you remember that and how that simple song Jerry used in the staging to advance?

Speaker I think once they had the song, they probably had a meeting that we weren’t privy to, but at the first rehearsal we had Gertrude Lawrence there and. He he worked on his feet with this what I’m sure he did a lot of preparation, but he devised that as he went along with Gertrude Lawrence. And of course, it’s not only the dance, but there’s a lot of integration with the song in between. So it’s all interwoven. And then the soloist, Mikiko, the fact that he probably just picked and chose what he wanted her to do, she would show him things and he would probably say, yes, let’s do this and then do that and then do this.

Speaker And then he made a little part of her with Michiko and Miss Azana, and she got the fan and then they danced together.

Speaker And then there was the kind of joke about the hoop skirt and and Michiko getting children to be her hoop skirt, that’s all. Jerry So he had that kind of wit and charm in his work to very amusing. Very delightful. I would love to talk about the palace dance, which is very new. We’re going to get oh, you are going to get there.

Speaker We’re on the way. Oh, all right. Yeah, but we’re on the OK. Oh.

Speaker Just before we do, one thing about getting to know you that I think is a remarkable tell me if I’m remembering this correctly, is that she doesn’t she’s not sure she wants to stay because she’s had a difficult time when she arrives. But somehow the way he staged it by the end of the song, she has decided that she’s that right.

Speaker Can you know, I think that by the time we get to the schoolroom scene, which is where we have getting to know you, she has already decided to say they are already school, has been in progress for a while. So that decision was made in a scene earlier after. Hello, young lovers, that song with the one she’s and after the parade of the children when she’s introduced to the children. That’s the sequence, it’s after the children, OK?

Speaker Talk a little bit about shall we dance?

Speaker Oh, uh, well, there again, Jerry had two masters to work with, your brother was a wonderful dancer. He could do anything, moved like a canine cat, like, you know, and and also a great sense of mischief. So and there was a lot of. Chemistry and electricity between the two stars and, of course, the two characters to have chemistry going on and Jerry exploited that, and it’s it’s much more easily in a dance than in dialogue because dialogue begins to get very open with dance. It’s more subtle and yet it’s very palpable.

Speaker Good. OK, um, so tell me about the making of the small house of Uncle Thomas.

Speaker And there are a few things about the previous small house that I’m not sure of, and I keep meaning to ask the archivist that Rodgers and Hammerstein if there’s any record of this. Probably not, but we worked on a long, long dance. Before small house of Uncle Thomas, because we were in one theater and the actors were over at the St. James, so there wasn’t much communication with the main company all day. And so then when Rodgers and Hammerstein came to see this dance, which I think later became part of some of that technique that we learned and even some of the passages went into the small house. But I don’t think that had been conceived yet. At least it hadn’t been conceived as a ballet. Maybe Havenstein had written it just as part of Jim’s education and her becoming a rebel and wanting to change things, but I don’t know for sure because that was all with the book people and with the powers that be. But the day after we had another run through where we were with the main company and all the staff was lined up along the front of the stage and they watched what Jerry had done. The very next day we had this new material. And. So I guess Rodgers and Hammerstein, it must have been working out that they couldn’t have come up with it totally overnight, but truly Ridvan did the music and as most times they the pianist with the choreographer maps out the music as the dance progresses. And then it’s she goes home or he goes home and writes it and makes it into a musical score. But the sketch will be done as the choreographer works. That was certainly true of Agnes and Jerry. I mean, Agnes and Trudy and also with Jerry in the King and I so. The. There was all the pantomime in the beginning where Tuptim is talking and Yuriko is doing all the gestures of crying and and look for love, George and all that and the dancing part of it that didn’t involve anyone except the three characters, Uncle Thomas, Little Eva.

Speaker Who’s the other one?

Speaker So, you know, the three Topsy, so I don’t ask you just go back and tell me just give me an overall idea for somebody who’s never seen the mind, what is what is it based on and what is how does it move the story forward in the case and what is its place?

Speaker I see.

Speaker Oh, what is the place of that story based on? It’s based on a story.

Speaker Now, what’s the name of that book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Yes.

Speaker And if you just if you could say the title of the valet as well.

Speaker Yes, OK. In The King and I, Oscar Hammerstein, came up with the idea of using the story, which was a famous story, and when it was written called Uncle Tom’s Cabin. And then he translated that idea into something that as a an Asian princess would translate it into it. She called it the small house of Uncle Thomas and. So at the beginning of the ballet, each character is introduced, Uncle Thomas Little Evea, mischief maker, Topsy and Pluralize, and they come in and they are introduced in mime and dance.

Speaker And Tuptim keeps talking and they do a happy dance. And then finally, King Simon of the Gry, which was Tuptim idea of her king. And I mean, it became obvious as the ballet goes on and the performance goes on, that she really is thinking of the king himself. And so Jerry made a wonderful entrance for Simon. He was supported. Sitting very regally like this with his sword on the hands of a man, one of the dancers way up above his head and two other slaves are beside that man holding Simon’s calf, knee and ankle and big red banner flies on. And Simon comes in and, you know, he has a big mask on and then jump and then he starts beating all the slaves.

Speaker So Tuptim talks. There’s wonderful music that Trudy wrote.

Speaker But Tuptim also is narrow, narrating through much of the the whole ballet so that it’s both written and sang and danced and spoken ballet.

Speaker So could you just explain again, for somebody who’s never seen it, that it’s sort of a play within a play, right? Yes. Look back on what’s actually happening in the court.

Speaker Yes, Tuptim is the new slave from Burma and she’s in love with somebody else. And she doesn’t want to be in that court. And she would she wants to escape from there. So the whole thing of Eliza crossing the ice and escaping is very much what Tuptim wants to do.

Speaker And eventually this play that Tuptim has written with all of her peers in the court. But we are all slaves to. Is presented when the British ambassador comes to visit, and that’s when it comes out to the king himself, that that’s what Tuptim is up to. And that is the beginning of the end for Tuptim.

Speaker Tell me about your role in all of this.

Speaker Well, getting back to rehearsal. One day, Jerry called me into the center of the floor by myself and. Everybody else was sitting around and besides reading your knitting or doing whatever dancers do when they have a few minutes rest and. He started showing me things that were. Quite easy for me since they were things that were similar to the things I learned in class from Nomura, and so it was crawling along on my knees and going through from getting up to the floor and, you know, and balancing and just all kinds of techniques like that. And I was going along fine and I was quite comfortable and happy with it. And then Jerry suddenly said, Now I want you to do when you want to say Huntelaar foot is up in the air, said, I want you to growl like a lion and or a tiger. And in those days, dancers never open their mouths. I mean, this was a. Revolutionary idea. We never even breathed so you could hear it, and if a choreographer, I wanted to go through the floor, I really the heads from all over the sides just looked up and zeroed in on Jerry and me in the center of the room and. I really would love to have just gone through the floor, but then if the choreographer says growl like a lion, you try it. And I started doing all the movement and going with her, and I wasn’t afraid of that because I’d had some acting, but not in conjunction with dance and.

Speaker Jerry began doing it with me and the two of us were going away doing all this movement and after about, I would say, 15 seconds of doing this, which seems much longer than that, but couldn’t have it any longer than that, I began to see what he was after. That sound makes you move in a way and use this part of your body in a way that you normally wouldn’t do in that same movement, you could do the movement without all that. But as soon as you start putting vocal sounds to it, it changes the quality. And by the time we finish that little session of teaching this section, to me, I it was a revolutionary.

Speaker It was a revelation to me. That’s the word I want. I realize what how valuable this was. And I’ve used words, especially with actors. If you tell an actor a word, he’ll do it and he’ll do it better than the dancers in the world because he does it from the total connection of mind and gut and muscle. And it just it’s automatic. And and of course, now the technique is used. I think this technique had just begun to be used with method acting and Stanislavski and Jerry had been studying and he studied everything. You know, I’m sure he’d been in taking directing classes and acting classes and movement classes. He was very well rounded in every way as far as his profession was concerned. And so more and more dancers began using that as a technique. And of course, then you had people like Tutor, Anthony Tutor and Agnes de Bill and a few other choreographers in American Ballet Theatre. At that time it was ballet theatre and they created all these great dramatic ballets. And they all had to be motivated.

Speaker Let me ask you about in the small house of Uncle Thomas and then if you can just tell me a little bit about, you know, what it was. Mm hmm.

Speaker My role in a small house of Uncle Thomas, of course, was King Simon Legree and. I guess Jerry must have said something to me and I might have figured it out myself, but I began imitating Yul Brynner as his his character. I began seeing his soliloquies and some of the scenes, you know, I was able to watch because I wasn’t in most of the show except for the small house and.

Speaker Under the mask.

Speaker Of course, I didn’t have the mask until we got very close to performance. I found that I without even thinking my face was doing what you always doing and. John Fernleigh, who was assistant to somebody, I forget what his job was at that time, he remarked on it one day he said, You look so much like your when you’re doing Timon and. So I think consciously, consciously, I began I had begun to imitate your brother and so. And that was a top Tim’s idea was to have King Simon represent you’ll you’ll Bernice King, so.

Speaker Allies, of course, was represented, was representing Tuptim herself, so Tuptim was trying to escape and at the.

Speaker So all these characters are telling the story of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and relating it to the king’s court that she was living in, and it really is the view of the king’s court from the eyes of the slaves who lived there. And eventually it was a play within a play because it was the way they do the play for the British ambassador and it is furthering the undercurrent story that’s been going on. You have the real court going on and then this ballet tells you exactly what’s going on in the undercurrents of the lives of the people in the court itself.

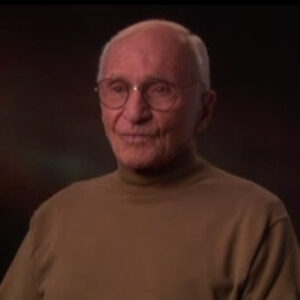

Speaker Right. I mean, now you mentioned surely written in before. She’s, I think, one of the unsung heroes in Gerry’s work. So could you explain to me if she was what her job was and what was her importance?

Speaker And now Trudy Richman, who wrote the music for so many musicals, she did a lot of the dance music. I have to qualify that for Rodgers and Hammerstein and Lerner and Low and others. But those those two were the main ones. And they she was brought to them by the choreographers. And then she became very close to Dick Rogers, to Lerner and Lowe, to Mr. Lowe especially, and.

Speaker An invaluable to all of the choreographers that she worked with because she wrote music to express their thoughts and ideas and choreography. She was not recognized for what she was doing really until many years afterwards. She was given a salary, but not credited with the amount of work she did.

Speaker Now, when we did the film of The King and I in Hollywood, she used to gamble on orchestra because they could afford it. They also have them out there.

Speaker And she did all that translation of the regular American Western instrumentation into the gamble on. And so all that wonderful sound that you have in The King and I movie has been developed by Trudy. And of course, you always worked in conjunction with Richard Rodgers, but I saw that there was a big but the big connection was with the choreographer and Jerry relied on her totally. So did Agnes do. They all became very close collaborators and friends.

Speaker I, um.

Speaker Before we get off the musical aspect, could you talk a little bit about anything you might have observed of Jerry’s relationship with Dick Rogers and also about Jerry’s innate sense of musicality himself was a musical. Hang on one second. Whoever is making that noise, please stop.

Speaker All right, do you want to celebrate? OK, so OK, so, um.

Speaker So the connection between Dick Rogers and Jerry.

Speaker I don’t think it was very friendly, actually. He was Jerry could be difficult and. Rodgers and Hammerstein really didn’t get to see the good part of the rehearsal day, they only knew about the bad part and. So I remember Jerry White, who was there, their production stage manager, he had to stage managers under him and either Jerry himself or one of the others would appear at our theater, which I thought was the broadcast and pretty sure one minute before quitting time to be sure that Jerry didn’t get one minute overtime.

Speaker I think that some of the dancers who knew the stage managers were complaining about how cold and miserable we were. And we all had this image of being in a it was not entirely Jerry’s fault, because part of it was that theater and the cold. And we all have a vision of just being in a dark tunnel all day and Jerry not being kind and warm and loving to us, made it even colder. So there wasn’t a great friendship there. And as a matter of fact, Jerry was very angry with the management for a long time because I don’t think he was adequately given royalties that he should have been.

Speaker I don’t know the whole story about that, but it’s it’s partly that there was some animosity there.

Speaker Tell me about Gerry’s musicality himself, was he musical and how? Give me some examples.

Speaker Jerry was I think he played the piano quite well, if I’m not mistaken, but at least he knew a lot about music. He was great friends with Lenny Bernstein and they were like colleagues. And and he he understood and had studied music thoroughly. So he was a very. Musical person in every way and knowledgeable.

Speaker I think most of the really good choreographers, especially in the golden years, they all were good musicians.

Speaker About the two stars, how they related to Jerry and how Jerry related to them are the two stars really liked Jerry very much. They got along very well. Jerry was giving them wonderful material. He always treated them with respect and he enjoyed working with them because they were so good and they could do whatever he asked them to do and they did it willingly. So those rehearsals, I think, were productive and fun and pleasant. And I think that they were friends. Just tell me who they were. It was Gertrude Lawrence and you’ll bring her something happened here. Oh, Gertrude Lawrence and Yul Brynner and Jerry especially working on her songs. And they’re both soliloquies. He helped with those.

Speaker And of course, Shall We Dance was, I think, probably a lot of fun for them working that out, you know.

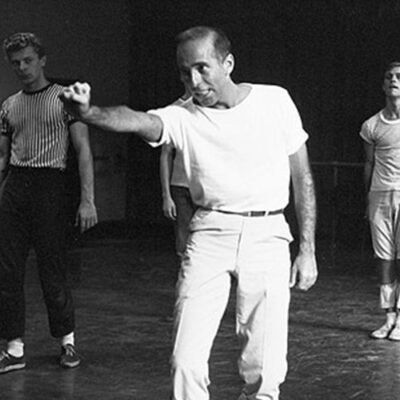

Speaker Jerry, communicate his ideas to you and. You talked a little bit before about the kind of dancer he was, but I’m wondering if you can give me some sense of what it would be like to be in a rehearsal with him. I mean, he wasn’t sitting in a chair, right?

Speaker No, he was on his feet and showing, demonstrating, creating as he went along. My mind is kind of going off into a tangent because I’ve been wondering about why there was this kind of animosity around up to a point, because he did do things once. We had to rehearse above a garage because something happened with rehearsal space and we all were beginning to get quite ill from the fumes coming up from the garage. I remember having a terrible headache from it, and I think any reasonable choreographer would have said, well, let’s quit for the day, but not Jerry. He just kept on and. It was mostly the core who got the brunt of it, because he kind of left the soloists out of the rehearsal at that point, whether that was on purpose or not, I don’t know. But word like things of that nature would get back to orange and that would make the rift because they were very polite, kind, at least outwardly. So all of us are a little mean sometimes, but primarily the working rehearsal with them was very civilized and very pleasant, very productive.

Speaker How would you distinguish, Gerri, from other choreographers, for example, Agnes, with whom you also worked? Mm hmm.

Speaker Well, Agnes did an awful lot of homework, too, and study.

Speaker I’m gonna stop you because I said to myself, oh, right. Yeah, right. So you start again. Yeah.

Speaker Sorry, Michael, I should do the middle myself, because in those years, I did call her Mr. Bill.

Speaker Now, Agnes Dumbell did as much preparation as Gerry must have done, I’m sure, and I was I spent more years with Dumbell than I did with him, although I did do fancy free for him and ballet theater. And he came and rehearsed me. And that was a wonderful experience to have him actually there helping. He was very helpful in that. He was not mean at all.

Speaker But I was there when Agnes the would have teachers come like an Irish step dancer and really experts on when we were doing judo and because that was all Irish dancing. So we had lessons in it and we went up to the Bronx to a party where they were having, you know, a ballroom and joined in the dances with them.

Speaker She brought a woman from England to do square dances and all of the Renaissance dances, we had classes in that, if that was the thing we were doing when we were doing comina, her assistant was not in charge. And so I helped her until they really got into rehearsal. She had a man named Mr. Opelika from Ghana and he had his drums would arrive. He had his drummers would arrive at ballet arts and we’d go off to the small studio. And the other part, the eighth floor and the drums would start. And Agnes and I would be going along at around and around the studio doing whatever Mr. Opelika was doing. And we did that every day for, I don’t know, a couple of weeks.

Speaker So how was it different working for Jerry than it was?

Speaker Well, I only did the King and I with him, so but I know he did the same thing with other shows to whatever the style was.

Speaker That’s what the preproduction work was. And they all did extensive work like that because the the even the really good dancers, they didn’t know how to do these other styles.

Speaker And so he had to teach the style, get the style onto the bodies before we started rehearsal, or they never would have gotten that done.

Speaker And of course, it was not legal because we weren’t paid for that, but we were delighted to do it, you know, so nobody cared that they weren’t paid. They were just thrilled that they were part of this process. Even if they didn’t get the job, they were happy about it. But mostly they did get the job.

Speaker Would you say that Jerry was a realist or a perfectionist and how did that affect the people he was working with?

Speaker He was Jerry. Jerry Robbins was a perfectionist. He knew what he wanted. And mostly he could do it himself. And he just worked at it and picked out it and went over and over and over it until you got it and.

Speaker The night before we did the the the last.

Speaker Big dance in the Ballet of the King and I of Small House of Uncle Thomas, which is really coordinated dancing, everybody is doing the same thing.

Speaker So it all had to be together and the positions had to be he went over bar by bar for an hour at the end of the day.

Speaker Because it wasn’t good enough, wasn’t right. Yeah, so he did work that way.

Speaker Would you say he was a decisive worker or not, and can you give me an example, a decisive worker?

Speaker I don’t know how else to say it, what I just said, that he really was meticulous and in every detail.

Speaker But was he the sort of person who came in, said something and that was it, or was it the sort of person who came in and tried out a lot of different things?

Speaker I see you want to know if he would come in with quite strong ideas and choreography, but if he wasn’t satisfied with it, he would change it. And that goes back to his ability to give you five or six versions of the same thing within a couple of minutes. So he was malleable in that way for himself, I think, to if he saw something in a dancer.

Speaker He used it.

Speaker For instance, he knew that Yuriko brought things to the part of Iliza that were unique to her, and so he exploited that, he exploited her great training and that she had certain muscles that other people didn’t have and a strength that, you know, a lot of people didn’t have. And certainly with Michiko, although all of the steps were of her devising, he was the one that molded them into a dance and into a meaningful dance and used all of her qualities.

Speaker I think even with me, when he realized that, he probably realized that I had nimura, in spite of the fact that we’d never met in the studio, he would have recognized it. Because my technique was very much affected by it once he started using the king and I the king’s Simon Legree’s steps and choreography, so he extended it more for things that I could do.

Speaker So he was very flexible in that way.

Speaker Did you have a sense that he was secure in his artistry?

Speaker You know, he I think he was very proud. He knew he was very talented, but I think he was insecure. And I think one of the reasons he could be difficult was that of his insecurities. In fact, when things had gotten so bad that we the dancers really weren’t working very well. He got us all together and told us about his therapy and his problems with just this particular subject of insecurities. And I’m not sure he had ever done that with a company before.

Speaker That’s extraordinary. Yeah, it was.

Speaker He must have felt really bad in order to share himself that way and open himself that way. The company?

Speaker Yeah, I think so. It was. Hawg.

Speaker He, I think, was the sort of I saw this myself, he’s the sort of person who treated different people differently. Yeah. So what was your relationship with him of at parties?

Speaker He was very friendly and warm and even flirted a little bit, which was nice. It was fun in the rehearsal hall.

Speaker It was just business, he he never he never picked on me, he didn’t pick on anybody who really gave their all and worked hard and could deliver. But he could be cruel to somebody who was having trouble and he’d find the weak point and stick the knife and twisted.

Speaker He’s not the only one who did that, but now you’re asking me to compare against the bill and Terry. I just never did that. If she seemed like she was being cruel, it was thoughtless thoughtlessness more than anything else. She could be reserved. And people took that for coldness. But she was reserved. She came from that heritage and. She was different in chorus rehearsal where she had the entire company than she was in the smaller rehearsals with her soloists. She usually would come into rehearsal. And if she’d had some interesting bit of news about politics or about life in general, she would educate us about it. Just a little anecdote. And we got a good liberal arts education from her over the years. But then she go to work. But she could tell she was very wry and make fun of herself and make fun of the situation during rehearsal.

Speaker But she was wonderful in the small rehearsals because she was warm and and enthusiastic and it was a real collaboration with all of us. I remember especially working with James Mitchell and Trudy and me alone was fantastic.

Speaker Just going back for a moment, do you remember what the reaction was to the show?

Speaker Oh, it was an enormous success. Oh, I’m sorry. Yes, it’s me, right.

Speaker I shouldn’t have also. I didn’t answer the question or ask the question. Um.

Speaker Now you want to know about the reaction of the audience, I suppose, to the the opening, we were in a little bit of trouble in Boston and they changed some songs. They took them out recording like they always do out of town with Broadway shows.

Speaker But the reviews were good. The reaction was very good. When we opened in New York, it was a smash hit right away. And the response to Small House vocal Thomas was, I think, as much as four, shall we dance? And some of the things that the stars did. First of all, everybody in the whole cast was first class and the Irene Sharov had done wonderful costumes. She had introduced Tai Silk’s to this country for the first time. And I remember she would take a piece of silk and wrap it around you and pin it and then take you out of the back to put it to see or to do that with this gorgeous material. First time she did it on me, I thought, oh my God, how can you cut that? But she was brilliant. Everybody connected with that show. It was brilliant. So it paid off. It’s still running, you know, somewhere in the world.

Speaker Well, then you all went to Hollywood. Tell me what Gerri’s role was in the movie and what what did what was his function and how did the movie people feel about him when he arrived?

Speaker Do you remember that?

Speaker When they decided to do a film of the King and I for 20th Century Fox, Jerry gathered his dancers from other companies that had done it and many of the originals you had your uncle and you and me?

Speaker Well, not not in the beginning. He didn’t have me. I was in Europe with another company, and after about three weeks of rehearsal out there, I was back.

Speaker And something I never told Jerry was when the studio called me, I was just getting over hepatitis. In fact, I think I might have still been in the hospital, but they said that I’d be all right in a couple of weeks. So of course I said yes. I couldn’t bear not to do. My role, so fact, I think this is the first time I’ve ever said publicly that about that, but it had an effect on me because first of all, I came in late and I was replacing somebody that Yuriko had given the part to, and Jerry wasn’t happy with her. So I came in and I felt a little bit in left field, even with my old friends, because they were already a team and I was the newcomer. It got better as time, but I thought that I became more friends with some of the Hollywood dancers than with my old pals. I think Jerry was highly respected by everyone that he worked with in Hollywood, but he did a couple of very foolish things. He wouldn’t listen to Trudy and to the conductor and a sound people. So when they were doing the orchestra recordings, he insisted upon having the entire company there while it was recorded and truly begged him to let them just record it and anything. He wasn’t happy with any tempo that was wrong. They would redo it. And both the conductor and the production stage manager, everybody, but he wouldn’t listen to it. We sat there still as statues while they recorded on the floor of the soundstage, which is cold because it’s right on it’s concrete on top of concrete. And then he would play it, had them play it back and we were supposed to get up and dance. Well, you know, you’re not going to get performance level dance at that point, no matter how hard you try, it just doesn’t work that way. He even had little Buddha who has nothing to do with it there on the set and the snow snowman and the prop man. So all these people were being paid overtime. We were there until eight or nine that night, I think. So that’s big overtime. And we did two days of that.

Speaker Uh.

Speaker So that, in other words, by the time there were a couple of other things like that that happened by the time Zadik I think came back from Europe and he saw the budget and he said, well, the ballet is wonderful, but it’s not worth three quarters of a million dollars. And so that was a big black mark against him. And I think he was trying to find himself to find a proper respect for himself without understanding how Hollywood works. I think that happens to a lot of New York people. It’s. Takes a little while to learn the ropes. It’s a different mindset, it’s a different set of values. And what’s important, the thing that I found absolutely wonderful was that. The the costumers and the people, the dressers were so solicitous of anybody from who was in front of the camera to cool you off with Seabreeze, especially in the back of our necks, because the stage was very hot. We were working with very hot lights and the floor would get so hot that we couldn’t stand on it. They were on top of all of that.

Speaker How did you get in? How the dancing was shot?

Speaker Oh, he was very much involved. He was there with, you know, having his say with the cameraman. But then again, he didn’t take advantage of film. When the guards, you know, the chase, Eliza goes across, the dogs go across, Eliza goes across, the dogs and guards go across the next time as it goes across.

Speaker And all you do is go out the way and you have eight, 12, 16 counts maybe, and you come back on target.

Speaker And the last one is, of course, Simon with the whole entourage. And the stage was wider than our New York stage that we were used to so that you had farther to go. And if you watch really carefully and you know the choreography, you see that there’s a there are not all together on the entrances. You know, it gets a little sloppy.

Speaker And.

Speaker That was not a smart thing to do when in Rome, at least pick up the good things at Rome does, and he just felt that content continuity was important and it really wasn’t in this case, you know.

Speaker I think those are probably lessons he learned very well, that he then later, yes. Yes.

Speaker Um. What did you learn from Jerry?

Speaker Well, he he, like Agnes, was erudite, knowledgeable, so you always felt that you are learning about theater and about history, about art.

Speaker They had great respect for the people that came before, like he freely admitted how much he owed to Jackhole, for instance.

Speaker And.

Speaker I I was used to that, and I think most of the dancers of my generation were used to that because we were taught about Diaghilev and even going before that with the Russian saurus Russian ballet company and Kreuzberg and Isadora Duncan and all those artists, I was just part of our training and ballet school or dance school or whatever and.

Speaker I knew Mary Bigman was even though she was in Germany when I was a child, but I don’t know if she ever got to this country when I was I don’t know if she got here at all.

Speaker I don’t think she did, but.

Speaker So Jerry also brought us up on more contemporary things. He was very knowledgeable about jazz and contemporary modern music, so I was getting that popular commercial side of it, too, which even Balanchine and Michael Fokine were very commercial when they came over here. They did a lot of those big extravaganzas when they came and people forget that. So the reason they’re such good choreographers is that they’re they are commercially minded to.