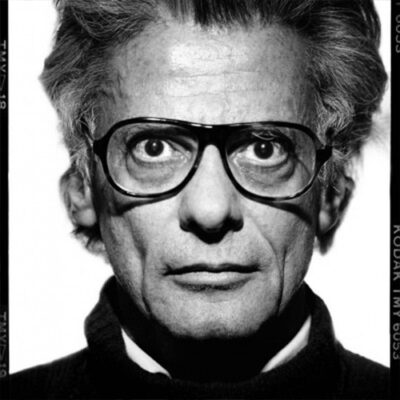

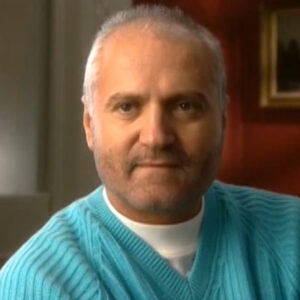

Speaker I’m getting a loan. Been working, was there for about fifteen years. From 1964 to 1980. Basically started as a second assistant. A year later became a studio manager and the nerve center of the studio.

Speaker Managing both here on Avidan. This time they were associated for a few years and basically concentrating on Richard, having done all his work, did all the lighting, printing, supervising assistants, going on trips with him, seeing the world together. Many fashion settings in Paris and around the world and Japan and Ireland and so on. And participated.

Speaker Many of the portraits that he has taken over the years of celebrities and others have done all the lighting and certainly the printing. I’ve done most of the printing for three of his exhibitions.

Speaker The Marlboro, certainly Metropolitan and the Museum of Modern Art have done some of the printing or the show in Minneapolis. And I delivered the last print on the show in Berkeley right before the opening. So we had a very long, productive and close relationship over the last 15 years.

Speaker You describe this as a great stimulation. It was it has been a very stimulating experience working with Dick.

Speaker I came from a small country. Israel studied in L.A. I got my bachelor’s degree in the arts and the culture of design and the governor, who was my first job in New York. And basically I came for a practical experience and then go back.

Speaker Those are the 60s and especially the 60s and then the 70s were just very exciting in the world of photography and fashion in particular. Was so much going on. It was such a creative time. In the studio between all the commercial work and all the editorial work that has worked for Harper’s Bazaar with very long days. There was a normal day. It was two hours, sometimes 18 hours, sometimes 20 hours. Certainly no overtime pay or anything like that. But there was a lot of creativity going on, a lot of stimulation, a lot of interesting people to meet. I was very, very exciting. Sally was the best studio in the world to work in, and Dick was very, very energetic, very with it, always ahead of the time, always discovering things he loved to have an international studio was people from all over the world who really got stimulated by it and stimulated other people. But there was such a variety of work that went through the studio and so many projects. I don’t think there was any other place in the world that I could get better experience. I had great influence on me in many ways.

Speaker I see things the same way as actors, although I come from a different point of view.

Speaker But we had the same sensitivity and sensibility about people and it was very interesting working close with them.

Speaker We rarely talked about what we were going to do. It didn’t have to say very much. I understood. I know I read his eyes. I knew what he was about to do and then working that closely, lighting with people, following their gestures just intuitively.

Speaker There was so much closeness and contact between us. Chemistry. He really was very, very unique. He really. I’m very much on my support.

Speaker And my name was called a thousand times a day just to take care of things.

Speaker This process, while you’re sitting at his own particular history. How would you describe the method of preparing the subject of the actual shooting?

Speaker What he did in the dark? You said he knew what he wanted. How did you see that control?

Speaker Dick was always prepared for his portraits. He researched the subject, researched personality.

Speaker He was always involved with interesting people. Known people. Was artistic people, writers, playwrights, musicians, actors. The world is a stage where everybody becomes an actor. And it’s true in front of the camera. But he knew enough about people, but their work, but maybe personal things that he could approach them. Make them comfortable. Put them at ease. And basically, the sittings were very quick. He was never a long, prolonged kind of portrait. Sitting was very painless for most people. Because it could engage them.

Speaker They could talk to them and make them respond to him and to the camera.

Speaker And the came at point were, you know, most people in front of a camera are very uneasy. I’m very uneasy in front of camera, but.

Speaker Comes a point where the person in his uneasiness become and becomes an actor. Really? He sort of covers up for his uneasiness and. The moment of truth comes when all the guards are dropped or he becomes comfortable with the situation or accept the situation. And.

Speaker That’s when the contact between the person as a photographer and the person who sets for him, they meet. That’s the point or the portrait that’s perfect. Because really very, very specific about what he wanted from a photograph, what he how the photograph should speak to us. So a dark room in the dark or there was a lot of it could do to enhance. And sometimes the negatives were beautiful and just came by itself. But many times I had to bring it out in the darkroom, whether it was through use of contrast or burning in or the usual dodging and so on.

Speaker But it was about bring out details and excitement in the photograph, the very, very delicate details in the photograph.

Speaker Whether it was the eyes, if we want to make the eyes very dramatic. And we had to reach out to whites just to make them pop more or like an insect Emerson’s face, I mean, the eyes just come out at you or the opposite. Talking about as a pound, for instance, where his eyes are close, but all the little folds in his eyes. And that’s very, very expressive. And be a shame to miss all that fine detail that makes the excitement in that photograph bleaching the highlights in their beards. So it really is alive. The same with a photograph of Twiggy. Was the flying hair making that hair really come alive? An exciting explosive. Her eyes just gazing out there.

Speaker So bleach came back. If you bleach very carefully, that’s something that is a very good tool. It’s a little easier with larger photographs because you can really get into my new details. And yet you have to be very careful because you can only see a photograph from a distance and sometimes you don’t see what you have done until you back away. And then sometimes it’s too much and sometimes too little. You can have a chance to fix it one way or the other through retouching or doing some more. Sometimes we had to combine negatives. I mean, when some very large prints like the Mission Council or the Warhol Factory Wall Factory, we actually splice two negatives together because he didn’t like he liked part of one negative and part of another negative.

Speaker And for his purpose, for his photograph, we had to do that. And unfortunately, one negative, it was a little thinner than the other one. So when we made those very large prints that were 10 feet high by 35 feet long, it was a matter of matching. And so a lot of work had to go into the in the darkroom in order to equalize and get a unique kind of print. These were three negatives that had to be joined together. So they had to have the same contrast, the same appearance. And if one half of one negative was weaker and actually contrast was a little weaker, it took a lot of work with a little bleaching just to equalize the contrast and the appearance of the print. You really learn to print when you make those very large prints. It’s a whole other world.

Speaker In a way, it’s easier. In a way it’s harder, because when you have to match pieces of photographs, because all these photographs were pieced together, because a paper is only so wide, it’s only 48 inches where the seams come together, where it’s joined. Those values have to be absolutely perfect, especially when you have graves. So holding back or changing the exposure by three seconds or two seconds, visually, it’s right there and it drives you crazy. Some of these printed to be done over and over until I got exactly the match sometimes because these were run through big machines. That machine were built for these photographs. It’s processing machines. If the machine was. This law, because the print was long or whatever, you would see a difference, and that sometimes drove me crazy.

Speaker The big picture, perfect size.

Speaker Sighs Well, I think because what? Probably the originator of these very tremendous prints. I mean, there were like enormous sculptures. And they were bigger than life. And he wanted these people to be bigger than life.

Speaker And they were very effective. They were very difficult to print, but they were very effective. And I learned a lot through just doing it. I mean, there was one print where we had to match fatality. We did for the Metropolitan Show, the early work was all tinted.

Speaker We used warm tone paper and there was a picture of Susie Parker in Paris. And that large paper did not come in a tone paper. I had to I used t I experiment was coffee and tea to get a match and tone to match the other prints because that room was all one tone. So anything is fair game to achieve what we had to do for today.

Speaker I mean, it all came from there. I mean, he had the ideas and he, you know, and I had to execute, had to find ways of solving the problems. I was a problem solver in many ways. And one thing I learned early in life is in the studio that you never say no. You find a way, you think positive and you find a way. And also, you must know the rules and you break the rules all the time. So I certainly was trained with all the rules and I learned to break all the rules in order to achieve the effect that he wanted.

Speaker Just once again, describe the effects that he was looking for. Certainly at this point that.

Speaker In general, he always looked for beautiful quality prints. Very dramatic. I mean, we always took them over the edge. I mean, they were livelier than any other print because the whites were whiter and the blacks were blacker. And we made the faces jump out of those photographs. I think he pushed beyond just the beautiful print of the many average prints. I mean, they’re all good prints. I don’t think we’ve ever had bad prints. But the he was always striving to go over the edge, the perfect, the best, the most detailed, the most exciting print. If you look at a ticket, you’re just excited looking at the print, whether you like the photograph or not. Didn’t matter. Just that beautiful print. I think it was amazing. The high standards of anybody, maybe pen and hero are the equals as far as standards are concerned. And once you get used to that, nothing else matters.

Speaker Question. What do you think? Does seem your contribution has been to fashion. Siegel is out. What is.

Speaker I think both and fashion and portraiture has been always ahead. He has learned from the past. He has always looked at other photographers and was influenced. And then he took it many steps forward. Everything was more exaggerated, more excitement, more drama. You couldn’t miss an Avidan photograph. Whether it was a virtual photograph or a portrait. And I know photographers who have looked through the magazine say, I’m going to do this photograph because it wasn’t half done. Everybody was copying him. It was amazing. When I start hearing those stories and you have seen copies of his work basically and many other photographers work cause they were influenced by him, his simplification abstraction in many ways were very uniquely his.

Speaker Suddenly the drama and the excitement around his work so much around other people. What are the buttons that he presses?

Speaker There’s a lot of contradiction in his work. I mean, you can see the difference between his fashion work and his portraiture just in treatment. Well, you see, his fashion work is all retouched and beautiful, absolutely exquisite. And portraiture is all very detail and no attempt in retouching every imperfection is there. That in itself is contradiction. He wants to be known as a portrait photographer, and the world has really accepted him as an incredible fashion photographer. Part of it is because of all his editorial work over the years in Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue. That was his showcase. And most of the work was fashion. I think that that’s what the world has accepted. It was easier to accept and the portraits being so severe have offended a lot of people that can’t accept it necessarily. Nobody wants to see ugliness or accepted. They don’t want to see. I think people projected themselves into these photographs sometimes, and I don’t want to look like that. So they are repelled and I think critics have not allow them to be a portrait photographer, even though he thinks he definitely wants to go down in history as a portrait photographer. He has done all this commercial work. I mean, people know him. As you know, he’s on the headlines, the Times or the news or where very an old man can deal with Versace or Calvin Klein or the revelant or whatever.

Speaker That’s how people know him.

Speaker And yet he feels he has to do all this commercial work in order to support and be independent and in control of the work that is close to him, that is dear to him.

Speaker And I understand that.

Speaker I totally understand him as what he’s doing as a as a creative person. And really appreciate it. There is a lot to say for independence. Unfortunately, the critics don’t agree with him and see it this way and don’t allow him to be what he wants to be. I think that they might not agree was his point of view about humanity, about people.

Speaker I think is entitled to his point of view. And I really appreciate that very much as a creative person. His point of view is rich out. He sees himself in a lot of us. His point of view is, I think in many ways it’s all one big stage and we all acting through life right to insanity. It’s an unstable life. It’s where we don’t always have control of our ourselves. Or we pretend. I don’t think there’s one person in the world who doesn’t act every day somewhat pretending to other people and himself. I think he exaggerates it and he brings with article more.

Speaker It was very different. Well, the other setting was John Ford, the rascal. John Ford was about to surface. I mean, the severity of the man who was tall and was frail, too.

Speaker You can see in the face or some toughness, but just about textures. And it just says it all. Mean it’s like a sculpture was so severe. Circle of angles really laughed the whole time. I mean, I was sitting of. Full of energy. It was continuous simile and motion it non-stop. Just like photographs. Well ask or allow.

Speaker I was just talking and laughing and smiling and being very funny, being the way he was.

Speaker But just to see the contrast of those three settings between the tenderness and the approach to a Renoir and a very kind way asking if I was a crazy kind of setting. And then John Ford was very staid kind of study of surfaces.

Speaker Was quite an experience. And again, was Gracia. It was more tender and fun at the same time, but it calmed down and they really tried to make him more human rather than the comedian. I remember that Oscar Levant, who was just.

Speaker Really, like a crazy person, almost gestures, the intensity of every emotion was amazing. Next to John Renoir was all very delicate and very refined, and you could see those kind eyes looking away, thinking you can always see him feeling within.

Speaker And it’s interesting about the light using the daylight. Now, these portraits can see in or there’s almost glow that colorful, come swim with them and they light has a way of doing that custom with them because such a large source of light that envelops the subject, especially with a white background such as council on or on, and you can use it in a way to show textures in a very grave way. And you can use it in a kind way. And John Renoir was one of those places and the light was so beautiful that it just sort of glows from within. John, for that, it’s really much more textured.

Speaker And I think the face itself just took on the severity of the personality. Oscar Levant, we had a great day and a softer light. And you can see the pale. This was a movement of scrub and was a little movement in in a negative. So you could see slight motion there, which added to the craziness. But the lines are less defined and the textures and less define a softer kind of quality. It’s all daylight. And the use of it has been very different.

Speaker We get bad results.

Speaker That’s quintessential Dick. It doesn’t surprise me that they love these pictures. I think they’re all dick in his own way.

Speaker He would have loved to be a genre noir, the director and genius. He would love to be there with us. Ask him about a great appreciation for his kind of work. I think he he grew up with all that and it was very close. So I think it’s all part of that’s almost a portrait of him. If he could only be that, I’m not surprised. He really I think he relates with these people very much.

Speaker What’s what is interesting is, is always was interest in movement of some kind.

Speaker His early photographs, he had seen a lot of movement.

Speaker And he likes people on the edge and they’re really scared of was right. I mean, this craziness to go. I mean, with mental institution photographs. There was a certain correlation. He’s he’s looking. Sometimes he’s looking for people that have that kind of energy craziness off. Extreme. I don’t think he expected this from Oscar amount when we got there before we walked in. I don’t think I think he has not seen him for many years. I don’t think that’s what they expect him when it happened.

Speaker He was very excited because he really found this person said the word that comes up all the time. And he said himself to describe himself, whether it’s from museum curators, friends, family, colleagues, assistance is the word control or mean. He comes up. What do people find? What does he have to tell? How to express something. Did you ever saw.

Speaker Loves to be in control. I mean, I think any person in this world would love to be in control if they had the opportunity. I mean, that’s a director who likes perfection and he really wants it his way. I think through life experience, a phone that being self-sufficient fill self made independent, you can have that if you’re in control.

Speaker It was never a question of money for him, you made plenty of money as a commercial photographer, so it gave him the power to be in control or that was photographing or post photographing and retouching and doing collages and everything. He wasn’t control what he wanted. And the final result had his final approval on everything down to the engravings. He produced his own books. He financed his own books. He knew what his exhibition wanted to be.

Speaker He design his own exhibitions with help of people that he wanted to know whether it was Marvin Israel or be a fighter or was and sell or.

Speaker Etc. to. Saying his daughter in law, his daughter in law, Elizabeth Paul.

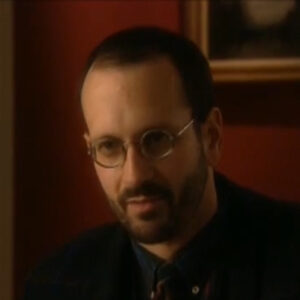

Speaker Now, whether it was Elizabeth Paul, the only one he could not control was Marvin Israel.

Speaker Marvin Israel definitely was a challenge to him.

Speaker And he respected him for that. And he fought him and he sometimes lost and sometimes our friends and sometimes of our enemies. But he had great respect for him because he stood up to him. And also, he got the most out of his work this way.

Speaker But he controls the media. He controls design. He controls everything that comes out of. They I have Adam as this big evidence. And I think if he had the choice, he would control the critics would control every article that comes out about him.

Speaker That’s his nature. And he’s drawing. Maybe, but.

Speaker He also manipulates people so he can get his way. It’s always about him. It’s not about other people. It’s about him. It’s about the governor. And it’s very selfish that way. And he has to live with it. Some people go along with it. So people move away from it. Their friends who have stuck with him forever and ever and have friends who have shied away from him because they don’t want to be controlled by him and feel it so unpleasant that he uses them.

Speaker But I think for him, it’s something that he really needs and it completes his creativity.

Speaker It just gives him the total image that he wants to create. And that is Richard.

Speaker Complete control is obviously a very rational, logical fence to make sure the work is presented in the right way.

Speaker But I don’t see what people say there are demons driving, it doesn’t work against against you the way it works. Over the years, she’s not always not always impressed.

Speaker And therefore, more complicated. I think that what you were talking about was the absolute best way for me to say no.

Speaker But it is also I don’t think he always has the best judgment about himself. I agree on that. But that doesn’t mean that he doesn’t still seek control, because this way it’s his responsibility. It’s him. OK. It is about him. It’s always about him.

Speaker For better or worse, that’s a decision he made and not somebody else. So he can’t blame anybody else. Can only blame himself.

Speaker Yes, sometimes it works against them, sometimes it doesn’t get the best out of what they should.

Speaker But it has to do with mistrust. In a way, he only trusts himself.

Speaker And that’s the fact is he did trust me for many years. I mean, he trusted everything I did for him. And they relied on me for specific things. And he knew he can trust. Everything would be perfect the way he wanted.

Speaker But he still has to have his finger on the pulse. He still has to guide everything. He still has the direct. Everything is the way it is about Richard. There’s nothing else. He is a very lonely person, too, because it’s all about him. Life is about him. I think every move he makes a consideration is marginal. He can be very generous. Final analysis. It’s about Richard. There’s a reason why it’s done it. There’s always a reason for something.

Speaker Once told me that no matter what you photograph, remember, you’re selling something. I mean, there’s there’s a focus on everything. It doesn’t do anything for just frivolously. There’s a reason. There’s a point to it. And he makes a decision. He’s controlling it. And it’s about him.

Speaker Before the competition, he said times extraordinary generosity, this could give you the credit.

Speaker I said he can be very generous. It can be very generous, especially when it comes to gifts and monetary things.

Speaker I mean, it was very easy for him giving away things.

Speaker But he was very stingy when it came to giving anybody credit.

Speaker If you look at his books, I mean, there’s very little credit given to anybody. It’s usually just mentioned names with other photographers like Pen. I mean, went on and on about their assistants, about anybody who contributed to any of their projects. Richard Avalon’s books or exhibitions? There’s very little mention. But anybody. Just the list of names. I find it very disappointing and really quite infuriating. Over the years. Because I know how much I put into projects and how much other people put into projects.

Speaker And he was not acknowledging in public. He could say it in person. He would complement. He would be very good about that, saying thank you and all that. When it came to the public image, nobody else really got credit except a few people like Marvin, his role.

Speaker So he actually once had a fight with Marvin Izrael about giving me credit when I was a Marlboro the Marlboro show. And I printed all those photographs and all the additions, took care of all the technicalities of the framing, everything helped hang the show and so on. And so he wasn’t going to give me credit anyways. And Marvin said, listen, you can do it, please. And the catalog, you have to give us some of the credit and eventually gave in and gave me credit.

Speaker That’s why I say it is really all about Richard done. And he keeps it very closely to him.

Speaker He’s a can be generous in some ways. But when it comes to his work, it’s has to be all about him. He does not share it with anybody. And that’s very sad. I find it very sad.

Speaker Could you talk a little bit about that kind of work you did for him?

Speaker And what can be done in the journey of a friend for the negative to life on a wall? Just what the range of options are. But one, I think this is the one I talk about.

Speaker Let’s start with lighting, I think. And then I’ll go to.

Speaker One of the.

Speaker Very important things that they developed.

Speaker Working with them was the moving light, strobe light, umbrella light.

Speaker And that’s what I did, is a handheld, a light first was two hands. Then I got strong. I held one hand. Bounce it. So I can hold a reflective card. The other hand.

Speaker And whenever wherever the face was, wherever the model was running to or from, the light was always in position. Just perfect. So it’s a beauty light or it’s a light that accentuate the eyes, whatever. But for bringing out fabric. But a light always moves the camera. Move the handheld camera. The girls were moving. I was moving. I mean, it was choreographed choreography at its best.

Speaker Nobody trained me to do that. That’s something that just happened.

Speaker I took over for a studio manager on Steinberger. And I think he started it. And but I don’t think he had the energy to do that. I guess I’m stronger and I was able to carry the light. And that’s what the light was. A light source was most of the fashion shots and portraits in the 60s, 70s until I left.

Speaker And I think nobody continued it after I left. It was a very unique kind of light lighting technique.

Speaker So between doing all the lighting for him, whether it was big sets, commercial sets or whatever, building sets, creating snow machines, whatever, I could design sets for him, whatever taking care of is all the technicalities of the studio. One of the big projects was to print and I think Dick started the early editions that photographers Dominique gave it. Great thought. Now we have debated many times and we came up with a standardized form of creating those editions. The first editions were of prints and negatives were given to the Smithsonian. And there were a of those things, 25 or 35 portfolio was printed.

Speaker There were 20 by 20 fours in the world. Portraits. Early portraits. 50S, 60s. That’s we put together, what, 11 of them? There was a first printed project. Some of it. I printed some of it. I have a Hungarian printer. Crazy Hungarian printer that I supervised. I think at the time, also the largest print I made was early 60s.

Speaker What all these pictures taken out?

Speaker Well, you know, it is interesting.

Speaker There’s a lot of things you can do in the darkroom with a photograph. And they rarely went into the darkroom.

Speaker I’ve never seen them print. I’ve seen here a print many times. And he is a master printer. Amazing.

Speaker And he taught me a lot about printing.

Speaker They never ventured into the darkroom except to look at the print and say, yes, no, whatever.

Speaker But in the darkroom, there’s a whole other choice of reinterpreting an image. Whether we look into it for a good print, what I mean, what it means, then the good print is to have beautiful, clear highlights. Whites and beautiful blacks, nice rich blacks and every shade in between. All the gradation. That would be a normal, beautiful, print rich, beautiful print. But that’s done necessarily the prints that one wants to make for that. It was a beauty print. You wanted to eliminate many of the tonalities, charred faces if it was a portrait you wanted to leave a lot in. There was a great concentration of eyes to bring the eyes out, sometimes to a little bleaching, just to make the eyes more intense. Sometimes we’ll have to send to the retoucher to do that. If then darkroom eliminating the unnecessary bring not the most important.

Speaker Just by shading, by burning in, by bleaching, dramatizing a lot about drama.

Speaker That’s the kind of print he really liked.

Speaker It was a rare occasion where he wanted a soft brand, kind of dreamy like photograph madwoman of Shiloh’s. One of them maybe, you know, always soft and so on. It did a lot of softening and sort of technique, I think in the 50s, Ray Rice paper or something to diffuse an image. But in the 60s, it was very real’s very sharp from blacks or very black and some of those early prints.

Speaker Even though the papers were much richer, you can’t find a beautiful photographic paper these days. The paths which blacks very hard to find in the 60s, we had dog show, which was just beautiful, rich paper, and many of the prints were made on that paper. And you can see the difference between the early prints in the 60s and then prints and violated the late 70s. Very different was much harder to get that kind of richness. Then I was introduced to making very large prints for us. There were 30 by Forte’s or 40 by my 50s for exhibitions. Those were printed modern age because we didn’t have the facilities in the studio. I could print up to four 20 by 24. Modern age, I do work with the printer. We like to collaborate or the printer and to collaborate with me. And we were privileged customers of modern age. They didn’t let any photographer in that RSM. And I established a nice relationship with a printer, especially with the manager of the lab, Elstree Hana, who is deceased. He was a real friend for many years.

Speaker He gave me the run of the place, basically. And the difference and making large prints on smaller prints is they were projected vertically on the wall where the magnetic wall or paper was fastened was magnetic rules. Paper came on roll.

Speaker So we just rolled paper down and we made those prints that who we want.

Speaker So that was the first big challenge. And it ended education. I found out that the biggest thing was to get over the fear of wasting paper because we didn’t do just test strips. We just made large prints and. Paper just went like nothing. And once you got used to the fact that you can just use paper and do the same as you work with a smaller print. Except everything is larger.

Speaker You can come in on details more easily. Use the same techniques on the you have even bigger tools or smaller tools.

Speaker Well, the tricky part came. Also, we could bleach in the big trays.

Speaker At first we used big trays, tremendous stress, and the paper would be rolled into the developer, into the chemicals, and sometimes will strengthen the developer or something. We can give our if we couldn’t get the exact contrast go in between and they will do a little bleaching. So that’s why I really learned how to bleach. Little details and faces, stuff like that. Al Soriano taught me how to do that. How to mix the bleach. Weak enough, strong enough to get what we want.

Speaker And the tricky part, can we read larger prints? Well, we had to piece together paper because paper only came forty eight inches.

Speaker Fifty 50 inches in the largest size. Largest width. We could go was forty eight inches. We just lost the light.

Speaker There are many options that we have in a darkroom to alter and enhance photograph. And one of the tools is bleach.

Speaker I mean, if you use bleach very carefully, you can bring out certain details that are almost impossible to get into print without that looking fake.