Speaker OK, well, photography as an art form for me is totally mysterious. Anyway, I love it. I love photography.

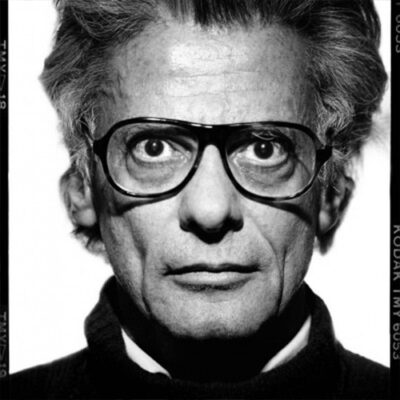

Speaker But Dick’s work in particular to me is totally mysterious because I remember some years back I needed an eight by 10 glossy publicity shot. You know, after I started acting in movies and I called Dick, I’d never ask Dick, you know. And I said, what was the name of that guy who used to be an assistant of yours who’s become quite a good photographer? And he said, Weiner, well, I need these publicity shots. And he said, What’s wrong? You don’t think I’m a good photographer anymore? I can’t do it. And he said, come on over. I’m doing some, you know, Revlon shoot or something. You said in a break, I’ll just do it. So I went over right away and Dick shot one roll of film. I think he shot it in four minutes. And I was just standing there. He photographed and as he would click, click. And that’s wonderful. That’s great. You know. You know, he was saying, well, I guess I guess as well as a glossy, he said, would you like a beautiful romantic picture for your parents? And I smiled and said, Sure. And then he said that, mate, maybe for the movies we should get one of you is a kind of sadistic, cold, ruthless, murderous SS man. Would that be good? Nice macho. And the roles finished. And sure enough, from the contacts came out, there was a wonderful eight by 10 publicity shot. There was a beautifully romantic picture for the piano, and there was this ruly, terrifying SS killer, Andre. And I never changed as far as I could tell. He was just talking to me and clicking and did it in four minutes and there it was. That, to me is total mystery.

Speaker Something about the both of you US directors.

Speaker Similar dissimilarities have been your Alice in Wonderland bouquet of wonderful quotes, metaphors, images you use to describe yourself as a director, a fisherman waiting, obviously doing more than just waiting. But nonetheless, the quietness of the waiting to happen and also the ways in which you would surprise people.

Speaker I was also struck in the book when you were talking about trying to make a male actor more male, but coming at it circuitously by asking him to go by address for his mother, who as he was having fantasies about doing this, no ambushing actors at the same time to get someplace that they might not otherwise get to.

Speaker You’re talking to somebody who is a total amnesiac. I remember three things that happened to me between being born and being 12 years old.

Speaker What were those three? One was when I had my tonsils out and the surgeon coming down with the scalpel. Another was watching my mother play cards.

Speaker And the third, of course, I forget.

Speaker Talk a little bit about if you feel there are similarities between rootedness and similarities or differences, class of directing between the two.

Speaker You know, I can’t really say about the actual craft of directing because I haven’t really seen him do it enough. I’ve just been, you know, had him do portraits of me and watched him shoot the Alice in Wonderland, which was so long ago. But one thing I think we have in common is the fascination between illusion and reality. When are we being authentic? When are we being theatrical? When are we being when are we acting?

Speaker What is the truth? What is the subtext? What’s below the surface? What? You know, the whole I mean, Dick you know, Dick travels 7000 miles or whatever it is to go to an opening of an Ingmar Bergman play. He showed up in London for the opening of our stage version of my dinner with Andre. He is truly the last of the great theatregoers. There’s nobody like him. You know, he saw Binya 40 times. He saw Alice 60 times, you know, not just because it’s mine. He does that also with Bergman’s work.

Speaker So for him, there’s a fascination in theater, in life, life, theater, something like that. And of course, my fascination is with the human face. It’s why generally now I don’t perform for more than 50 people. So you can get in close and getting really close. You know, if that answers your question also also, I had a sense that Dick was similar to me years ago in the area of energy.

Speaker I work with so, you know, energy. If you see the A-list, you know, and I think part of that was a disbelief that, in fact, we were alive.

Speaker Like, you pinch yourself to make sure you’re there. I think maybe I could just be projecting this on deck. But I know it’s true of myself back then. I don’t think I was ever sure that there was anything under the surface because I always had a great persona. That is a good thing to have consciously when you work and you need to manipulate the practical world around you. But I think I doubted there was maybe anything really under the skin. So, you know, that’s what my dinner with Andre is about. It’s going out to such extremes that you literally derri yourself alive right here. This is where it happened. The great Montauk burial was right here, because somewhere inside you, you’re not sure if you’re alive. Now, I don’t know if that is. You know, also, I think another similarity for sure, Dick, and I have is that my my best works hours, my dinner with Andre and Vine, you all eggs examine or explore. How close can you come to madness? How close can you go to the edge and still come back?

Speaker And of course, these decks, you know, fascination, obsession with madness, the pictures in the insane asylums, you know, so I think there’s there’s similarities for sure. They’re in themes and also in fine. There’s the whole theme of beauty and fading beauty. But I think that the the energy, the madness and the question of what is real, what is surface is one that fascinates both of us.

Speaker Well, yeah, there’s a lot of rage where they used to be a lot of rage in Dick’s work. And, you know, I don’t know about Dick, but I know that even when some people came up to me the other night and hit me in the face with a chain and nearly went to the skull, I had trouble feeling rage because I was brought up in such a polite, sophisticated, waspy way, even though I’m a Jew, that you never express rage. So I don’t even feel it very often. So I live it vicariously, say, through Wally and Vanya, which is a performance filled with rage, you know. And yet. It’s been a lot of anger in my work, and that’s certainly yeah, that’s another area that I think Dick and I have a lot in common now.

Speaker Like Dick, I think I’m trying to go somewhere much, much simpler, quieter in the direction of his portrait of Beckett or his portrait of me with Wally and Louie, the last one that went in The New Yorker, where you just look at it in all simplicity, like Eliot, T.S. Eliot, still. And still moving.

Speaker Does have the experience, but not this meaning of fight that we.

Speaker I think I think the thing that is so gutsy, one of the things it’s very gutsy about, Dick, is he lives his contradiction. He’s nakedly complex. And I I’ve always thought that if you wanted to write a great American novel about an artist of our time, Dick would be the subject matter, because most of us are. All of us are very complex. We just tend to hide it. And, you know, I think specially. Not specially. But this issue, this issue of, you know, the commercial and art which very few American artists have the courage to really live.

Speaker They go in one direction. You know what I mean? He’s able to stay in that place of contradiction, which I think is very gutsy.

Speaker And you know, I when I was in Poland, a young man had never met me before, shook my hand and said to me, When I look into your eyes, I see the saddest optimist I’ve ever met. You know, Dick has those and most of us do. So I don’t think it’s that he’s different. I think that he’s simply able to live the differences more nakedly than a lot of people are. I don’t have that answers. I mean, you know that he’s so apocalyptic in the same time, he’s so playful. Well, it’s natural that he lives like Speckhard. There’s a line in Endgame. The end is in the beginning. And yet we go on. You know, I was very aware from a very early age of death and have I think been by nature a rather joyful person in the east. They believe that the closer we live to the weirdness and perception of dying, the more we’ll be able to live our lives. It’s just in the West that we have this black and white, you know, this or that.

Speaker He talks about really looking for faces that are filled with contradictions. Can you think of portraits that you feel are especially rich in that?

Speaker Quality of the contradictions.

Speaker Well, chaplain comes to mind that great portrait of Chaplain Brett comes to mind.

Speaker Marilyn.

Speaker But almost every portrait he takes because we are contradictory. You know, it’s why I take years to rehearse a play is to get down to the complexity. Everything in our culture now that we’re being fed by the media says it’s this or that. It’s black or white. That’s not human. To be human is to be dense, mysterious and inexplicable. And I think that’s what Dick goes after. And that’s always contradictions.

Speaker He simply sees reality. That’s the way reality is.

Speaker What would the shape of.

Speaker It would be big, long, lusty, elegant. Tough.

Speaker You know, I assume that to exist in the world of fashion. You have to be very, very tough and very, very ruthless. I just assumed that I. I don’t see Dick operate in that world. But I just assume you would have to be. At the same time, he’s one of the tenderest, gentlest, most caring friends that a human being could possibly have. Most of us are that way. But we don’t like to admit it. I can be very, very tough and ruthless when it comes to my work, but I pretend it’s just easy and no one elegant and spiritual.

Speaker And it was interesting talking about men and friendships. It’s just different comments. There are crossover men and women. There’s someone you want as well. He considers himself a crossover. He’s a man who values friendship in a way that is a long conversation with me that I never cross over.

Speaker Yeah, well, I was. I don’t know about his childhood, but I always hung out with the girls. I played jacks with the girl. I danced with the girls. I always liked women because women were open as boys weren’t talking about the things that always fascinated me and obsessed me, you know?

Speaker And Dick is one of my few male friends that I can talk about the deepest things that are personal to me and my deepest worries and fears. And at the same time, talk about culture. You know, people today there are very few people who take an evening to talk about books, politics, art, painting, life, death. You know, there, too, he’s he’s odd now. Most people and you know me. I love to do that.

Speaker What are the other single qualities, qualities that might exhaust you, make you crazy to think of your qualities, a friendship with other ways in which Dick is a friend?

Speaker Unique.

Speaker Well, one way that one way that he’s a unique friend is that he loves you most. When you’re in trouble. When you’re not in trouble. I think he just sort of assumes it’s OK. And if if you’re in trouble, if you have real problems, he’s there day and night. Some other people will get scared by that and disappear. It’s quite the opposite with Dick. You know, like he said about one of the baby pictures yesterday and I was talking about this baby that was beautiful and tranquil and exuded calm and he said boring.

Speaker So maybe he gets bored. It’s like going easy in your life. But he’s really there when you’re in trouble.

Speaker 1970. Yeah. I met him in 1970 when he started obsessively coming to Alice over and over and over and over again. And that led to the writing of the book, the Alice book. So it’s nearly 25 years.

Speaker I just that opening when you saw this man again and again and again.

Speaker Oh, for sure. Not meshuggener, because I’ve seen productions of things 40 times. 50 times. I know. I think the first the first thing that struck me was that he just brought into this world this amazing whiff of the glamorous, the elegance. You know, it was interesting yesterday when when he was showing his work to everybody around the table and the pictures came out of the fashion pictures, the Paris fashion pictures, everybody on the crew, you and everybody. Now, it wasn’t that they were great pictures. They were obviously not great pictures that you can cut. But there’s something about that world that is, of course, very glamorous. And he brought all of that, you know, and Fred Astaire and Stanley down and world and a very romantic world that. All seem to come in the door with him. I think that was that was the very first impression.

Speaker And then quite quickly, when we got to know each other, we went to these intense conversations about very you know, I don’t know.

Speaker I remember, you know, I almost never remember reviews because they aren’t worth anything. And they’re mostly written by morons. But Ted Kallum from TIME magazine called Alice a vertiginous descent into a laughing hell.

Speaker And maybe, you know, there’s on one on one end, there’s the pictures in the Mad House and the Berlin Wall and then the other. There’s Mike Nichols and the fashion and everything else as the laughter and the madness. Also, I just assume that Dick had a terrifying childhood. I just assume it, although we talk very little, oddly enough, about his childhood, we’ve talked a lot about mine. And Alice is the definitive terror story, terrorist story about about childhood, you know. Other than that, I don’t I don’t know.

Speaker But something grabbed him. And it is interesting that he considers those pictures absolutely central to his work now. He played an interesting trick on himself. I think we do that. You know, he was up against a wall at that time and he was just about to break through this thing about being an artist and to take that leap. And I think he was up against a wall. He published the Lartigue book, I think, because he can’t not work so that that was work to do. But it wasn’t him because he couldn’t find him at that time. And I think Alice, he played a trick on himself where he could say, well, it isn’t me, it’s not my work. We’re just doing it for the fun of it. We’re doing because I love Andre and his work. And in taking that pressure off himself, he was able to do some of his greatest work.

Speaker Francine said, I would have felt that. Talk about Proost, very obvious at heart. He’s a frustrated novelist. He talks a lot. He has talked a lot about the limitations of photography. That can be a floatation, a sentence, a paragraph, but never a chapter.

Speaker You feel that? And do you feel that, A, that’s true about him wanting to pour somewhat more into a photograph?

Speaker What can.

Speaker Well, in in relation to Dick’s love of Proost, I think for sure his last book, The Big One, is Proustian in its exploration of time and but also time, you see is unique in the performing arts to the theater. It’s all about time and it’s very close to life in the sense that every night you’re born, you come onto the stage, you struggle a little bit, you laugh a little bit, you flounder a little bit, and then suddenly before you know it, it’s all over and the performance is forgotten, except in the distorted memories of those few people who saw it. So it is a life and death every night and time, I think is essential to the photographer’s work and seeing inside time, if you know what I mean.

Speaker Whether. Whether.

Speaker His pictures can’t you said, like his pictures can’t contain everything it is that he wants to say. That was his. He said that much more that shows that he can’t put in the picture. Well, it probably does if it does. But also, I think that’s part of what gives those pictures that amazing energy again. Again, it’s Beckert, because in Beckert, a character is up to his neck in a trash can.

Speaker And inside that trash can find as much life as you possibly can in a trash can. It’s like having one foot in the grave and another on a banana peel and still dancing like Mickey Rooney. These are the limits of living. The end is in the beginning. And yet we go on. We only have so much time. We know we’re dying, and yet we keep living. It’s that awareness that can lend a real energy to the act of living or the act of creation. So I think the result in Dick’s work is part of what gives it that bubbling volcanic energy underneath the surface. And it may be frustrating to him, but it’s lovely for us.

Speaker You think he’s a closet?

Speaker I have no idea.

Speaker Probably on the one hand I’d say not, certainly consciously not. Or closet the closet spiritual person, on the other hand. I don’t know how you can spend your entire life dealing with light and not get some perception of the mysterious story about Dick wanted to show Johnny’s son when he was young.

Speaker The Russian war and peace that I think lasts 12 hours or something like that. He had a special screening in Paris and they had blankets because there was no heat in the theater and they had vodka and they stayed up all night. Dick Dick does that. He takes reality and heightens it, which is, of course, what I considers the nature of style. This is what I do in the theater. I take reality and I heighten it. You know, when we went on our first European tour with Alice in Wonderland, Dick said, this is hotel. You have to stay and it’s great. I reserve your room. You go there with chickweed and the kids. It would be wonderful.

Speaker We get there and the walls and the ceilings decorated with loops of candies for the kids. And there are balloons and their gifts on the floor. Shoes for me. Something for Jackie to welcome to Paris. Welcome, Alice. You know, he does that.

Speaker He does that.

Speaker Which is very generous and very theatrical.

Speaker Talk a little bit about that series for the magazine. The idea that the idea that the pictures that resulted from it really did cause sensation.

Speaker You know, I don’t know. I don’t know about the ideas behind it, because then I was just this passive male model. I just showed up like all the girls and had my makeup done.

Speaker You know, I know I know that I’d only made my dinner with Andre when I did those that campaign. And I actually learned a lot about movie acting from Dick in those months that we did the Deora ads, because, of course, you know, you have to show the tie.

Speaker You have to stand like this, your head, you know. But shoes, you know, show the shirt, you know, the laces, everything. And at the same time, my function for him was to be a trickster. Spontaneous, improvisational. And keep the energy going with the other two. So I had to learn. And again, this is Beckett. Like, how can you have all of that energy life fun improv within this thing where you show the tie and everything like that. So in fact, I learned a lot about acting within the constrictions of the camera. That’s just something personally, I got out of it. I know a lot of people found the ads kinky, I think is the organization called Now.

Speaker They you’re seeing the pinioned describe the story.

Speaker Well, there’s this sort of Kinki May nage at y you know, you’re never sure who’s sleeping with who or who’s doing what to whom. I’m the older one. They’re these two men and this beautiful woman, you know, they’re very suggestive. It’s sort of Noel Coward with a slight little pinch of the market aside. Very sophisticated. Very weird. Very kinky in a way. Not kinky. Odd.

Speaker I loved them because, like my work, they allow you to imagine. They don’t tell you what to think. You do the storytelling. Each one of you who watches these ads, is it him and her? Is it both of them with each other? Is the three what? What’s going on here? So in fact, they allow your own imagination to work. I was also very proud because I think I I broke the age barrier for models.

Speaker I was the first old male model.

Speaker You could just break a fidget a little bit of that discussion at the very end portrait sitting about truth and portraiture, what the class was bringing up and what if he does have a position? I think actually he has to achieve it just well. Well, there was a very interesting discussion about what what what are we looking for in the portrait photographer? Leaving aside the audience, is there itself there would be old fragmented way? Or is it the powerful image, the fiction? I guess I’m asking that just because that seven minutes of film was destroyed.

Speaker Oh, what a shame.

Speaker So that’s why I ask you to go. Okay. Right now it’s just a blur.

Speaker Well, it’s that, as I remember, one of one of the women in the class was talking about going after what somebody really is under the surface. And I think Dick said maybe the surface is it maybe. And I. I myself think because of all this pop psychology that we have and because Americans want to just leap into the New Age overnight and we want to do everything quickly.

Speaker There’s this assumption that you can tell who a person is, which I totally don’t believe. I’ve spent too much time in my own life, you know, working with therapists, with meditation, spiritual teacher, you know, trying to find out who am I. This is the central question of almost every religion there is. Who am I? It takes a lifetime. So this idea that you can just get under the skin with a shot and tell who the person is I think is nuts. I think you can get intimations, Cloo.

Speaker Was.

Speaker You know, sometimes you can tell a lot from the surface, from the way a person holds their head in their hands, the way you’re doing right now. The body language, the way a person walks. These are all exterior things. You can tell a lot from just picking up the feeling or the emotion inside you. The simplicity the dick is looking for. Now, the sort of essence there when somebody is often doing nothing, you know, you’re doing nothing now except listening.

Speaker But I can tell what I think I can because in fact, you know, in the East, they think there are only two real things that ever happened to us.

Speaker We come into the world and we leave it. That’s real. That does happen. Everything in the middle is just a dream. You know, I project my needs onto you. My feelings onto you. My desires onto you. And I think that’s who you are. Dick, I don’t think makes any bones about that. I think. Doesn’t he say he’s really he he takes a picture and he’s talking about himself.

Speaker I think what’s interesting is that he wants it both ways. I think one says something like that biography on your face.

Speaker And on the other hand, I think he is best old fashioned humanist. There is a self self there. Maybe we only get intimations of blues fragments, but that he is interested in revealing a few of those fragments at the same time.

Speaker So I think it’s both.

Speaker I think depending on who’s talking door is moot or he’s furious at the silly criticism of his portraits or the unsophisticated vocabulary of critics.

Speaker Dealing with photography. And I think he’s in a totally fiction mode, which is it’s fine. And Satan’s apples are his apples and these faces are my faces. But I. I also feel he’s.

Speaker Fascinating personality with the stuff that makes us different than our neighbors.

Speaker He is digging. He’s always digging. Yeah, he’s always digging. And it’s like I said this morning, I think if if we ever thought we’d found it, we’d stop working.

Speaker I think part of our work is this eternal search for the self. I don’t think we do it.

Speaker If we weren’t looking for who we are and we do it sometimes monks do it alone. Most of us do it one to one with another through another. Side by side with another.

Speaker But I’m sure he’s looking for the self and feels that some of his more that self is really all that and others.

Speaker I mean, I was this doesn’t have to do with that at all. But I wish this probably isn’t relevant. I was thinking of the Brandenburg Gate pictures because there’s also the sense of the artist as prophet, because when everybody, the whole world was celebrating the wall coming down and the changes in the east deck already saw the eyes and the bodies of those people on the Berlin Wall, all the anxiety and chaos that’s happening right now. And of course, that isn’t always easy to live with that kind of either conscious or intuitive knowledge. I think.

Speaker Portraits of people that he’s taken, you know quite well.

Speaker And again, mystery to each other, more mysterious or less mysterious, depending on the level of intimacy that we have that you feel.

Speaker That’s something essential. Not ultimate truth. None of those grand words. But he’s cut through to something and you know that person as well. Their portraits?

Speaker Well, oddly enough, I’d say the portrait he did of me with Louis and Wally for The New Yorker.

Speaker People sometimes say to me, you’re so spiritual.

Speaker I don’t know what the hell the talking. No idea what they’re talking about.

Speaker And in that picture, I could see what these people see. Also, you know, in these last years since my wife died, I’ve been in this odd process of trying to find out who I am now alone without her. And I often don’t have the slightest idea. A lot of time, I don’t think. Who am I now? Who is this person, you know, who’s walking home to an apartment all by himself? I never lived alone before, you know, new friends. And so in this picture, I saw me. It literally it helped me. I look at that picture and I can say, this is me now.

Speaker This is who I am. I get it. He got it. And I get it. It’s an older person. It’s somebody who’s not angry the way he used to be. It’s somebody more simple, somehow quieter.

Speaker And he got it. And that was enormously helpful to me. I don’t have it up on the wall, but I should. I don’t know if that answers your question, Wally.

Speaker I don’t know, because, you know, it would depend on how Wally feels about himself. Now, he sure got Wally Vanya.

Speaker You know, I think it’s more complex. Talked about it that day.

Speaker What was your response to that particular portrait? You know what?

Speaker The complexity of it was very moving. It was very moving because there’s a lot about young cuts, life that we might be very judgmental about if we knew about it and if it were true. But it’s very important to forgive.

Speaker And, you know, it’s it’s very easy to throw stones at people who gave names during the McCarthy period. And I think it’s a horrible thing, but none of us know until we in that spot. What will do and most of us are very protected. Young Codd, who grew up in Eastern Europe, you know, was in the Warsaw ghetto, I think was one of the leaders of the Warsaw Rebellion. You know, I gather was a Stalinist. That’s a person like Bertold Bresh that’s put in a position, you know, we know better. Bresch now is revolting and slimy, you know, and other people acted better in similar circumstances.

Speaker But we can’t judge because we weren’t in these people’s shoes. And what is lovely about the portrait, I think, is that you see the vulnerability, the illness.

Speaker There’s something that has a lot of forgiveness in it, even if it doesn’t know the whole story.

Speaker Here’s another I’d like to see that one, do you have the oh, I love that’s particularly interesting. Gutowski Gutowski said that in Poland they always find the McCarthy period here mazing because in Poland, the issue would be to turn a friend in because your life depends on it. But the idea that people would turn a friend in because your job depends on it, that’s for them. Inconceivable.

Speaker They have a point.

Speaker What’s sad is that people do go on, do so many of them film, have lived with that and felt their lives were defined by other people who behaved a lot better.

Speaker My complete and the rest of our lives are free of that burden. Did you read the book naming names? Cause he was what he was? Yeah. That’s a great my consultant. Yeah, it’s a great looking film.

Speaker Another person, another portrait of dicks that actually I did feel this is without judging but didn’t go to the heart of complexity of the man. This is revealing. That New Yorker article about him was a Brighton Brighton back. Right. Right. I didn’t know that. It’s just a fascinating South African dissident, White, who went to jail and was broken in jail. And by his own admission, you know, no gang names and confessions and, you know, just track lines of life must be written on this man’s face. And I think he was very much in control of that setting.

Speaker And the image that was projected, at least for this project, was that it was saying. Which I think would be the last that he would sing if he would say about himself. Good. I haven’t asked him anything that you like at all about basically Dick and his work on Monday. Nothing. Nothing that I can think of particular. Certainly gets very confusing, the heat around his work around the man. I mean, I’ve rarely encountered was taken by surprise, much of it. He showed me life thoughts about that.

Speaker I’m not here yet. OK.

Speaker It’s worked. Just. Why does he get attacked, savaged the way it does? I think it’s partly envy because he seems to have everything. He seems to be rich, good looking. Lives in a magical world. Makes a lot of money as a fine artist. I think it’s envy. I think. I think a lot of it is envy. Also, he may sometimes get caught because he has to make money to keep up this big thing and to make money. He has to do a lot of publicity around himself. He has to a lot of promotion. And I think I think critics think you can’t do that and be an artist because the American media does not understand ambiguity. They don’t get it. They don’t like it. They don’t want it.

Speaker So they see a person who is this and that.

Speaker A great artist and a commercial. You know, we can.

Speaker But if you’re both.

Speaker It drives them nuts. And I think on some level it’s political because I think these critics across the board are consciously or unconsciously members of a new totalitarian system that exists right here in which the creative person or the artist is a danger to the society the way they have always been in fascistic states, which this is now spend the night in in the hospital the way I did. And you will know that you have to wait six hours to get sewed up, because in our culture, it’s more important to have a Mercedes Benz than to have three people in that hospital taking care of the poor. If the truth appears now, they’ll try to get it. The truth is ambiguous, dense and mired in paradox. They don’t like it. Also, he works within the system. He’s able to do his work and get around it. It drives them nuts. They’re little gerbils. They are. They’re mean spirited little apparatchiks that are working for a system that at 11 o’clock every night fills the unconscious of America with rape, little kids being thrown down, incinerators, people being sheltered. You know, it’s a culture in which the media is trying to Namath’s these people work for the media and their job is to squelch the truth wherever they can. So it’s also political.

Speaker And also, the totally meanspirited, envious note, his work is powerful.

Speaker It’s upsetting.

Speaker It’s upsetting. Absolutely. Yeah. What he has to say is very upsetting.

Speaker And we’re we’re living in a time when we don’t want it. Why? Why are we conservative?

Speaker We’re conservative because we’re in such chaos that we want to conserve anything. Hold on. Hold on. You know, and anybody with a truly apocalyptic vision, which I don’t share. I don’t have an apocalyptic vision. But he could be right. You know, these are strange times. And somebody who says, look, look, who says look and says it’s crazy, it’s disintegrating, it’s madness. You know, that’s upsetting. And people know they don’t like to be upset.

Speaker They’d like a quiet, sweet thing. Now that I think that’s part of it, too, also.

Speaker Also, you know, when when people get. We never get angry unless it’s touched a nerve. We just don’t. You can say to me, I’m a child killer and I’ll say it because I’m not, you know, but you touch a nerve and you’ll get me and I’ll have an emotional response.

Speaker An exaggerated emotional response always psychologically means. A nerve has been touched, you know. And I think he touches some kind of nerve. I’m not sure what it is.

Speaker Ending that some of the sessions that are disturbing.

Speaker Just trying to say in many different ways.

Speaker Well, we we we live. I mean, as you know, we live in very terrifying times. We’re doing we’re doing ecologically to ourselves. You know, our our passivity in relation to what’s going on is not unlike. I don’t think the passivity of Germans, average Germans in the 30s.

Speaker And when somebody says, look, look at what’s happened. You generally want to kill.

Speaker You know, I’m different because I actually have a lot of hope.

Speaker I’m always trying to go towards the light. But it also is out of despair and terror. And I’m very conscious of what’s going on now. So he’s dark. You know, his book where it goes to at the end of his book, you know, the madness and the Death. And, you know, that’s dark and people get scared.

Speaker So I photograph most afraid. Yes.

Speaker You know, you look at books and movies and television now, and nobody wants to deal with this stuff. Of course, the problem with that is repression and denial always makes it scarier. So if we’re in real denial, which I think we are a lot.

Speaker Now somebody come along and say, hey, take a look like that for you personally.

Speaker What’s the most frightening picture along the lines of what you just.

Speaker You think the best, uh, you know, I think, um, uh, I think the most frightening picture is the one on the Berlin Wall.

Speaker Because I think I think he sees there a kind of, Kate, political chaos and dis integration and a potential fascism coming out of fear and terrorism coming out of fear, that is for sure. Bosnia, he saw Bosnia before Bosnia happened. You know, he saw Rwanda before Rwanda happened, all on the Berlin Wall and everybody celebrating you. You see, that’s a very scary picture for me.