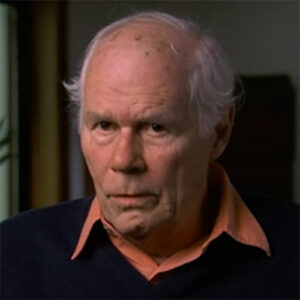

Michael Kantor: What do you consider the start of Broadway?

Brendan Gill: The start of Broadway is almost the start of Broadway as an actual physical entity in the city of New York. Because the Dutch began Broadway. It was the main street of the little village that the Dutch founded, and the British took it over. And it became their Broadway, and it ran all the way up as far as legitimately you could claim it goes all the way to Albany by now. And always on Broadway. There was theater from the very beginning, from, say, when Washington was the inaugurated president here, there was theater on Broadway, so, and one of the reasons that there has always been theater on Broadway is because Broadway breaks up the gridiron of New York, which is laid out in 1811, and a very severe, brutal pressing down of a gridiron upon a naturally marvelous island of hills and dales So Broadway broke the gridiron, wherever it crossed the grid iron on its way up to the Hudson River and then to Albany. And wherever Broadway broke, the grid-iron, there was extra energy. Something happened. And that was always the theater district. And almost not quite in my lifetime, but it was 14th Street and then 34th Street and then 42nd Street and even up to 57th Street. But there is something about smashing the gridiron that it causes a kind of. Explosion of energy, and that was always where the theater lived, and it’s a thrilling fact about theater that it moves like that, not only with population, but where energy is. Theater is consummately based on a disciplined energy.

Michael Kantor: The Black Crook is often cited as the start of the American musical theater. What do we know about it?

Brendan Gill: Nothing except, I think, or I know nothing about it except as one reads about it in history, but it was a melodrama and from the very beginning there were people who were trying to write serious plays and then there were the people who are writing melodramas and melodrams were thought to be a fairly low form of entertainment. It was the equivalent on the theatrical level of vaudeville, really, but it wonderfully thrilling and they were always great. Deeds of Daring Do, and The Black Crook, I think, ran for decades in one form or another. And out of it grew the subsequent, not only musical comedy, but also a new kind of melodrama, the murder mystery and all that other kind of thing like that. But people were, I believe even in what was at its most popular, people were sort ashamed of going to the black crook and enjoying it. We have always had that sort of snobbish feeling about the theater. Sometimes we’re ashamed to enjoy certain low forms of art, like a murder mystery on the stage, which we really prefer, in many cases, to Hamlet, which is itself a murder mystery, but on a rather lofty level.

Michael Kantor: Or with scantily clad women, who were Harrigan and Hart?

Brendan Gill: They were a famous comedy team, and actually Josh Logan’s wife, Nina, was the daughter of Harrigan and Hart, and they were vaudeville, which was the supreme form of traveling theater in the United States in the 19th and early 20th century. People were on the road continuously, and Harrigan Hart were very funny, and he who were also representative of what was then. An honorable situation in the theater which was ethnic, ethnic humor, now we’re so idiotically sensitive to anything ethnic, we’re afraid of hurting anybody’s feelings, it’s not possible to have that kind of ethnic, only Jackie Mason remains making terrible remarks about Jews which he gets away with because he keeps reminding us that he’s a rabbi or the son of a rabbi, or the brother of a Rabbi. Which he thinks justifies what he does. But there aren’t things like that anymore. And there was the Irish humor. And there were Buster Keaton’s family was Irish comedians. Harry Gunn and Howard were Irish. Webber and Fields were famous. The Bauderville team was Jewish. Jokes back and forth. And of course, there was black humor. And nobody, the blacks were extreme caricatures of black. People, and everybody laughed. Well, nobody laughs anymore at the least ethnic thing, except we’re only allowed now to laugh at white Protestants because there are so few of them, and the pretext is that they wouldn’t get the joke anyway.

Michael Kantor: Great, that’s so terrific. Let’s just go back and just synopsize that very quickly. The late 19th century on Broadway was a time for that.

Brendan Gill: The late 19th century on Broadway was very much concerned with, on one hand, melodrama, not very important kinds of theater, drawing room comedy, which is much more what the social people would want to go to see, and then vaudeville, which was of course the great theater of the masses. It was what people really went to see and is now, is banished without a trace or almost without a choice because it all went on television and radio and television absorbed what we used to have as vaudeville. And they were the great comedians that were all, usually they were paired off two by two in some way on an ethnic basis.

Michael Kantor: Who is George M. Cohan?

Brendan Gill: He was, by all accounts, something of a scoundrel. He was an impossible human being. But of course, if you were as successful as George M. Cohen was in the theater, if you weren’t born impossible, you become impossible. In any event, he was a tremendous actor, comedian, showman, and he wrote great popular songs. I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy. And Mary, that’s a grand old name, and all the small things that you could imagine, and they were wonderful. And then he acted in his own plays. We could claim him as a kind of somewhat lower class Noel Coward in that he wrote his own play, he sang and danced in his plays, he produced his own place, but he was also a very tough character who… Didn’t like the notion of unions or in fact he didn’t like anybody else to have any particular protection as long as he was well protected. But he was, though not an endearing man, a tremendous figure in the theater and can be seen as representative of really the most inventive kind of American theater at that time and also with technical tour de force that’s going on. Jockey, horse racing and all that kind of thing. And he exists now in most of our memories, not as George M. Cohan himself, but as James Cagney in the movie who played George M Cohan so well that that now becomes for us, or for most people, George M Cohen.

Michael Kantor: But he sort of came from Vaudeville, from the family of the four Koans, and then really by the time he was done, there was musical theater, wasn’t he?

Brendan Gill: He was, yes I would certainly say he was a bridge and was also trying to, well he inserted more plot in things and, but the chief thing that he did I think was that he knew exactly what kind of music ought to be written. Noah Coward himself says in Private Lives playing his own Someday I’ll Find You and then he has the character saying, strange how potent cheap music can be. That was what George M. Cohan was wonderfully doing, and he was a pleasing, a very pleasing figure on stage.

Michael Kantor: What about the Ziegfeld Follies, what was their attraction?

Brendan Gill: Well, of course, it was beautiful girls, it was Billy Rose later on who talked about the long-stemmed American beauties, but making a joke on his name, Billy Rose, and that kind of rose. But it was, Ziegfeld was for spectacle. And it was really the only remains of that kind to spectacle was the Rockettes at the music hall, where there was a kind of technique of mass. Women doing things all together, or drifting down flights of stairs in exquisite costumes. And it wasn’t anything like as erotic as you would think it would be, because nothing very much was going on. They were simply exhibiting themselves in a fantasy setting. And then along with the beautiful girls, with the fantasy setting, with a wonderful sets, many of which were by Joseph Urban, a Viennese designer and architect who came over here. And designed the Siegfeld Follies, many of them, and also built the Sieglfeld Theater for the follies to appear in. But then, of course, there were the great headliners who were part of the review. It wasn’t a musical comedy, it was a spectacle. And then Will Rogers or a half dozen other famous comedians would come on and do their turn in the follys. So it was mingling of light-hearted nonsense and… It was the easiest thing in the world for people to take. And it was at that time that people spoke of the tired businessman. What did the tired businessman want to go to see? Well, of course he wanted to go see either the Ziegfeld Follies or George White’s scandals or something like that. I interviewed the other night of a sweet little lady who was 92 years old who had danced in the Zingfeld Follys in 1922 and 1923. And among the stage door Johnnies that existed in those days came backstage with bouquets of flowers to court these chorus girls, were gangsters. And I said, well, how did the gangsters behave? And she said, they were very well mannered. And then I said well, what about Mr. Ziegfeld? He was very well-mannered. So her memories were very happy ones.

Michael Kantor: What was maybe George M. Cohan’s most famous song, Give My Regards to Broadway? Give me a hint of that and tell me how it reflects on where Broadway was at that time.

Brendan Gill: Well, in Cohen’s day, of course, 34th Street was still the great theater district having come up gradually from 14th Street to 23rd Street and then from 23rd to 34th, then it went on to 42nd. But Cohen’s great song, Give My Regards to Broadway, Say Hello to Herald Square, and then Tell All the Boys on 34th street that I will soon be there, that was what he was talking about. And then subsequently he too moved up. To Times Square, and then it all became the first World War. By that time, it was 42nd Street. And then by the time we were having the movies about 42nd street and all that, that was the very citadel of theater. And that remains, Times Square remains the citadel, the heart of theater of all kinds.

Michael Kantor: Great. Just coming back to the Ziegfeld Follies and the reviews and the scandals and so on, weren’t they a training ground for great composers?

Brendan Gill: Well, I think anybody and all the composers wanted to get into to do songs for the various reviews, reviews with the common form, which are much easier. You put it, you put them together, Helter Skelter. You’d have a star like a Will Rogers if he was able to do that, if he wasn’t under contract somewhere else, and half a dozen of them. And they’d all be wound in together, taken from tradition of vaudeville, but put into the musical review. So you had the beauty, you had this spectacle, and you had a comedy, and that was that. And then out of that eventually came, of course, the much more serious Hardin and Rodgers and Hammerstein musical comedy with plot and everything. But first you had the individual songs that you might write. And there was hundreds of songwriters hoping to get their things in. And the music box review was the things of that kind. Irving Berlin actually had a half ownership in the music box, and the review was an important place for him to do. Have his songs be played, and then it was a much more distinguished thing and much more profitable for everybody when the musical comedy was developed. And you wrote a whole, you wrote 15, 18 songs for a musical comedy which had the plot of a play in it, and that was a big advance.

Michael Kantor: I love how Berlin’s life story sort of mirrors this great immigrant rise. Can you?

Brendan Gill: Well, the whole thing was so thrilling as an American story, of course, that here was little Isidore Balin. He was an immigrant boy, tiny, wistful looking, kind of like, a little bit like Joel Gray, you know, that kind of a person. And beginning down in the Lower East Side in the Jewish Quarter was just extremely populous and dense and dense and full of energy and excitement. And he began as a singing, than writing songs. And becoming the great American song writer, you know, and writing things in the end like God Bless America and White Christmas and things like that, that people believe to be American anthems. They, many people now are under the misapprehension that they were written in the 18th century and that they are national anthems, not our national anthem. And, but Berlin was able to come out of an environment totally European. Saturatedly Jewish, Russian-Jewish immigration. And B, is so American in the transformation in a matter of 10 years, 15 years, 20 years. And think, you know, somewhat later than Berlin and on much more serious perhaps, more serious musical level, George Gershwin, also Russian-jewish family, immigrant family, comes to America and George Gerschwin and Ira Gershwin are writing. The most exquisite English lyrics that anybody has ever written in English. I mean, Ira Gershwin was writing like Gilbert and Sullivan almost at once. How could such a thing happen? It’s just perfectly wonderful that it happened. And that’s repeated 150 times. And so they gave us, out of nowhere, this great swarm of immigrant talent. Gave us what we then believed to be American. We became Americans through them, not there was a lucky few that were already here, but they became American at the direction of people who were never even seen America. And of course, this is going to be happening now and is happening now with the great flood of Eastern people coming in. We’re being transformed and wonderfully transformed and we don’t even know it.

Michael Kantor: People speak of Jerome Kern as the first truly American composer. Richard Rogers says, it’s not ragtime. It wasn’t middle European. It was truly American. Who was Jerome Kern?

Brendan Gill: Jerome Kern was, I think, the most exquisite of that particular generation of songwriters. Although, you’d have to say, you know, he’s also the same period as Cole Porter and Vincent Newman and two or three other people who are perhaps less famous now. So I wouldn’t say he was by any means the first story, even the best of those songwriters, but the most exquisite and his songs have a kind of both The sweetness and the tunes are… Touching and romantic, you know, as smoke gets in your eyes, it’s a very, you begin to become misty-eyed not from smoke but from sentiment when you hear a Jerome Kern song. But he was one of 30 or 40, and he himself, again from a Jewish background and becoming a great bibliophile. He was one the great book collectors of America. And they liked it. How their lives had turned out. They were very fortunate people, thanks to their great talent and the energy and discipline that they possessed. And he ended up, you know, in a grand house with a wonderful collection of books, living just as he ought to. He had become an American gentleman, and better than most of the American gentlemen who believe themselves to be American gentlemen.

Michael Kantor: When you think of the landmarks in the development of the Broadway musical, wouldn’t you say that Kern was associated with one major one, namely Schoenberg?

Brendan Gill: You know, the, I would think that that was certainly one of the classical American musical comedies. There’s just no way to take in how all those songs could come out of this. And there again, it was one of the early ones to be based on a novel by Edna Ferber in which it was translated into musical terms and the sentimentality of the original novel. Survived beautifully in musical comedy form. You can be far more sentimental and have a different kind of beauty in musical comedy than anything that you would possibly have in a novel, which is a much more serious and intellectually taxing form of art in most cases. But certainly in my lifetime, the showbo was one of the great things counted on to make me cry at every performance. Only make believe, and I was dissolved in tears, you know. But then, and then the other great one in my lifetime was My Fair Lady, which is also a classical breakthrough because there was no chorus. There was not a chorus line. They didn’t have people dancing about on stage. And it had intellectual content. It was sweet. Was based on something that nobody thought it could be based on, which is a play by Shaw. Shaw wasn’t thought to be likely to be a musical comedy author. And the first night of My Fair Lady, I knew perfectly well I was seeing something greater of this kind that I’d ever seen before. Julie Andrews at 18 or whatever coming back into the library, explicitly dressed and singing, I could have danced all night, I couldn’t have danced… Oh, that was tremendous. So we have all these milestones along the way. And then, interestingly, the whole thing seemed to collapse. It seemed as if we had used up something that had just reached its peak, its best. And this happens in art, and nobody knows anything about it. Same thing happens in painting. The same thing happens a novel. Same thing happened in poetry. And it leaves us aghast and bewildered. And then, on some level, ready to move on.

Michael Kantor: When would you target that moment of…

Brendan Gill: Well, I think in the last 10 or 15 years, it’s been very much harder to try to imagine writing a musical comedy, and with the result that we do have startling things like rant which came when we started everybody by its in-the-faceness, it was really a slap in the face, but a slap-in-the face that has meaning in its touching of its kind, and And if I can remember how to say, bring in the… Defunct, what’s the first part, bring into noise, which is a startling physical apparition. You can’t believe that human beings can exercise their bodies in that perfectly wonderful way. So there’s an exhilaration of performance there. But the content doesn’t really, is superfluous on any serious level. And so in recent times I think it’s been very hard to say where, if you were to in an academic way. Where is the musical comedy going? I don’t think anybody knows. So then we have, always happens, a revival, the whole system of revivals. We bring back Shell Boat, not in my view too fortunately. And we bring back out of the great treasure house of the past as much as we can bring back. And so we’ve had mostly, we’ve had revivals of musical comedies for the last two or three years more often than we’ve had successful new form of musical comedy.

Michael Kantor: Broadway can’t afford to die. Tell me that.

Brendan Gill: Well, the fact is in New York City, which is in many respects the greatest city on Earth to this very day, as we always boasted that it was, but the basis on which New York exists as a great city, one of the great cities of all time, was, of course, first that it was a great port, where we lost most of our shipping, so that basis that we had is gone. It was the largest manufacturing city in the United States. That’s gone. It now still has banking, Wall Street, all that, but that’s only one among many now. You can be banking in Bombay or Singapore or wherever you name it in the world. We’re one of many places. You bank overnight, 24 hours a day, anywhere. So that’s really gone, or going, or gone. And people are living in Wall Street rather than having offices in Wall street. It’s become residential. So, Broadway, which is to say entertainment. Is with communications, which is more and more a form of entertainment, the source of the existence of New York City for the future. From the year 2000 on, we’re going to be living because, as a great entity, continue to be a great city, because of, in effect, Broadway. And many people regret the fact that what used to be serious communication. That everything, thanks mostly to TV and only partially to Broadway and the Broadway view, the Disney-ization of life of our culture, is that everything has become entertainment. Politics is entertainment now, all too plainly. But sports, all the rules in sports have been changed in order to make it better entertainment to coincide with television and the commercials on television. So nothing that we do. Religion is now all entertainment. The preachers there in their glass cathedrals doubting and carrying on. Broadway is the quintessence of entertainment, and even if we don’t know where we’re going to go from one day to the next, in respect where does the musical comedy go? Where does straight theater go? Who are going to be the Edward Albreys of the future and all that? Because it is indispensable to the structure and life of New York City, a way will be found to make sure that it continues to exist. And this is a challenge in itself that nobody has to be self-conscious about. It’s just a fact. Of life, that this is the way civilizations work. And they either work like that and they find a new means of existence, or they die. And it doesn’t look to me very much as if New York was going to die. People are more eager to come to New York now than they have ever been in my lifetime. They’re much more eager from all over the world. And among other things, a great advantage to us, although we in New York don’t think so, is that New York is very cheap in the world’s eyes. People come here as tourists because it’s cheaper than anywhere else to go as a tourist. And so Broadway will profit from all these things which are non-Broadway intellectually or at heart, but which function to make Broadway succeed.

Michael Kantor: Who was co-oported?

Brendan Gill: Indeed. Well, he’s a favorite character of mine. I think you could say to begin with that he was adorable. He was a small man with big brown eyes. He looked rather like a monkey. And he had come out of Peru, Indiana, not a poor boy. His grandfather, after whom he was named, left in the state of $9 million all in cash because we didn’t trust stocks and bonds. But anyway, Cole came east, went to Yale, had this talent for writing, and could sing very well in his really little voice. And he was taken up at Yale by the big shots, the white-shoe crowd at Yale, joined a proper secret society, started a career as a composer, went to Paris to learn real composition under Vincent Dandy, who was a great teacher at that time. And then his heart was always, he was determined to become a Broadway writer. He wanted to be like Irving Berlin, he wanted to like Jerome Kern. At the same time, he’s rich and idle and a playboy and liked to be on the Riviera and liked his nice apartment in Paris. So he tried to have both worlds at once and he got him. He managed to do it and so he became one of our most popular musical comedy writers wrote hundreds upon hundreds of perfectly wonderful songs. With great lyrics and he, only Stephen Sondheim really remains among the people who as disciples, in Stephen’s case, both of Hammerstein and of Porter, continue to write lyrics that are amusing to us, that rhyme, that lift our hearts. Most lyrics and most songs that we hear nowadays, we neither understand nor care to understand because that’s a new vogue. But Cole Porter wrote based on partly on Browning, and partly on Gilbert of Gilbert and Sullivan, the most delectable rhymes. Rhyme after rhyme after rhyme, and also lighthearted.

Michael Kantor: What are some of your favorite Cole Porter witty ditties that way?

Brendan Gill: Well, you know, bees do it, everybody in the trees do it and, or I’m flying high like some guy in the sky and… Well, a dozen, he wrote about New York, sentimental ones, Begin the Beguine, and I think at long last Love. Every kind of song he was able to write, and some of them a certain touch of malice, which was very welcome at that time. And he was, um, uh… He wouldn’t say there was a happy homosexual, but at that time it was not permissible to be homosexual, and he was ardently homosexual and had wonderful and amusing companions all his life. He was married, but his wife was sort of a dead mother. But the whole, there was, again, if we had a submerged culture on Broadway of often racial origins and things like that where people were… Sort of coming up out of nowhere, we also at the same time always had this homosexual culture which had to hide itself because it was impermissible in our society, in part because it is against the law. There are actually so many laws against homosexuals. So Cole Porter and Hart and a dozen other people who were homosexuals had a very difficult time that way. They were living in a kind of secret society in the presence of society. And that’s something which I think nowadays, thank God, at last, in the 1990s and by the year 2000, were able to examine and study the degree to which this did have a powerful effect on the kind of work they were doing and they were trying to do.

Michael Kantor: So essentially you’re saying it’s part of the malice in the might have to do with the fact that he couldn’t live his life openly

Brendan Gill: It wasn’t that, yeah, he, because he was rich, because he was well-born, because seemingly a Yale jock, was able to get away with a lot of things that other people wouldn’t have been able to. But it was the strain to be closeted is a painful situation, and never to have come into existence. It was a series of cultural accidents of the 19th century. Nobody worried about this in the early 19th century at all. The condition of homosexuality was invented by a couple of doctors, really more than by anybody else in the 18th, 19th century, so what. But they were placed in a position which made it very difficult for them. It was true to some extent, but there was a less public worry about it among artists and sculptors and people of that kind. In the theater it was always a question that came up and had to be dealt with.

Michael Kantor: Co-porter had many playgrounds, but what do you think Broadway meant to him?

Brendan Gill: Oh, to be on Broadway was everything. He loved that. He really was, he wanted to be one of the boys in effect. He wanted to in there as a real pro. At the same time, he perhaps imprudently wanted to remain an amateur. So that he was, there he was on the Riviera. That’s not really where you’re supposed to be if you want to be in Broadway. There’s a lot of nitty gritty that has to go on as well. And fortunately he had collisions from time to time. That proved to be, despite his misgivings, proved to be very successful. I Kiss Me Kate, which he didn’t imagine could possibly be made into a successful musical. But imagine being able to write a line like, I’ve come to wive it wealthily in Padua. Oh, now that’s English poetry. That’s very good.

Michael Kantor: What was the central episode in Cole Porter’s life?

Brendan Gill: The central episode was a disastrous horse accident where a horse, of course, he was riding horseback at the Piping Rock Club, which is the fashionable club on Long Island, and a horse stumbled and fell on him and rolled over and broke one of his legs and then rolled over, broke the other leg, and eventually, and the wound on one leg never healed. He was supposed to have had it amputated and… Nobody could bear to think of perfect coal with his little immaculate body being mutilated that way. So he spent the rest of his life in extreme pain with an open wound, a superating wound, and had to be lifted into the theater on opening nights and things of that kind. So it was a terrible story for the last 20 years of his live, and he was heavily drugged toward the end, which gave him an isolation and simply a preposterous accident that had nothing to do. With who he was or who he meant to be and what ought to have been his career.

Michael Kantor: 1919 in Paris, Colport.

Brendan Gill: Colport was in Paris in 1919 after the war and in uniform, looking quite sharp. And he met through Yale friends of his, Linda Lee Thomas, this divorced woman who said at one time, at least, to have been the most beautiful woman in Europe, an American, southern American woman who had been married to another Yale man who was sexually a sadist and beat her up and she had no interest in sex. And when the opportunity arrived to marry Cole Porter, the fact that he was homosexual and that it would be what is called a white marriage, didn’t disturb her at all. And so she became a kind of den mother then for the gatherings of people that Cole, they always traveled with an entourage and with half a dozen guests going up and down the Nile, going around the world, whatever they were doing. It was all play, and Cole down on the Riviera and Noel Coward would come down to visit. There were wonderful, wonderful pictures of them in Venice on the Lido, and I’m sorry to say they called each other Noely and Coely, but these things happen. And it was charming. And then, of course, the tragic accident, and Linda agreed that he shouldn’t have his leg amputated, which was a mistake, and then she grew less and less interested and putting up with him. And he became more interested in his old age, or in his middle years, late middle years. In Hollywood, he really was infatuated with Hollywood. Again, as an outsider, he could afford to be infatuate, and he would lie by the swimming pool there, surrounded by golden boys of marvelous physique, which with whom he could at least fantasize something. And Linda finally gave up and came back, he used to live. And then he… Moved into the Waldorf Astoria in his last years and died there, heavily sedated and in terrible pain for many years. It was a sad, sad, sad finish.

Michael Kantor: How was Kiss Me, Kate a sort of return from the accent?

Brendan Gill: The Kiss Me Kate, he was astonished to think that Kiss Me Kate could be made into a musical comedy. And the Spiewaks, who were trained and very good Broadway writers, knew or were sure that they could turn the Taming of the Shrew into a Broadway musical. And so they convinced Cole that it could be done. And it was done. And it with a great success. And the songs are simply tremendous. And then he had the help of Abe Burroughs in putting together things. There were other people. All of musical comedy, of course, takes 20 people. So the songwriter is, of, course, a key, but there are 19 other people involved with the whole thing, and Cole was fortunate with those people.

Michael Kantor: While Cole wrote both music and words, which was unusual, his genius wasn’t sort of the unity of the book and the score, was it? It was more about the star turn.

Brendan Gill: Yeah, he wrote for people and he loved Ethel Merman. He loved that voice, you know, Ethel’s voice could cut through sheet steel. It was just an amazing, and it was absolutely true. It could go all up and down the scale and be absolutely true and absolutely penetrating and there was no question of amplification for her and he just loved that voice and he love writing for that voice. But there was always somebody that he would have in mind to write for, and that was also a tradition in theater, which was true both of the legitimate theater and of musical comedy, which has more or less gone out. Very few young authors nowadays would dare to think, oh, I’m going to write a play for just one particular actor. We don’t have that kind of mini-Madden Fisk star person who is waiting for people to write plays for her to act in. But that was their tradition. In the 18th and 19th century, which has sort of gone out.

Michael Kantor: Tell me the importance of critics to Broadway. What happens opening night?

Brendan Gill: It is a continuous mystery why critics should be important at all, because again and again it’s the case with previews that audience seem to be having a perfectly good time, and then the so-called critic doesn’t like it and then the box office collapses. Why does the critic have that power? He doesn’t have that powerful. People think he has that power. And I’ve always been puzzled as a critic myself for 15 or 20 years to know why my opinion matters to people if they’ve already held another differing opinion. Why wouldn’t word of mouth always triumph over the opinion of one man who may be in a bad mood or whoever knows what. I never call them critics anyway because we are reviewers, not critics, and what the purpose of a reviewer is to review a play or a book or a concert or something like that and report on it as a journalistic activity, it’s a journeyman job, you’re saying, this is my response X, Y and Z. It’s not an important activity. The real critic rarely does any writing in America. He’s the person who addresses himself to the work and his intention if the author is alive. Is to help the author, is to try to figure out what the author was up to, and if the author has failed to say to the author this is where I think this has gone wrong, well if anybody tried to be a critic on Broadway, nobody would publish him, a literary quarterly would publish a critic of a given piece of work, but what the reviewer does is a trifle and shouldn’t be thought to be more than a trifling and instead of that it’s a matter of life and death. It’s absurd, and there was no training to be a reviewer on Broadway. People stumble into the, at one time, to be movie critic, so-called critic, reviewer, was really the lowest job you could have on a newspaper. If you came in and you were a drunken, unfit character to be anything else, couldn’t even cover the police desk, you were given movies to review. Well, things have improved a little bit since then, but the principle remains the same, and it is truly mysterious. That audiences do not make up their own minds, and that they will listen to, and not even to 20 reviewers, but to two or three reviewers at the very most. It happens at the moment. Ben Brantley at the New York Times, I think is a very good reviewer indeed, and he is a reviewer. He’s not pretending to be a critic. But if anybody disagrees with him, why on earth would it cause them to change their mind?

Michael Kantor: Wasn’t there a time when there were so many Broadway shows opening that they’d send sports critics?

Brendan Gill: Well, in the old days, there would be as many as six or seven openings on a single night. And of course, the number of openings has increased in recent years compared to a few years ago. And there might be only maybe 30 openings in the course of a whole year. But it’s only one untutored mind against your own untutered mind, you know? And, and, uh… It’s very difficult for critics, for reviewers, I never, I just have to make sure I say reviewer, to utter just praise. Praise is very hard to write, especially in a hurry. Whereas mocking something or giving an adverse opinion of something is very easy to do. The machinery of now sets in. And we make wisecracks, so we tend to dismiss things, or we have a sentence that we can dismiss something in. This is something to be fought against, but it exists, whereas praise, oh, now what am I going to do? I have to praise something, and that’s hard. So, even professionally, there are difficulties, but that it should be so closely linked to economics is amazing, and there is an artificial situation is demonstrated by movies. Nobody pays attention to movie reviewers in terms of box office. Absolutely no. No matter what a movie reviewer says against a movie, no matter how devastating a review is, the movie is either a blockbuster or it isn’t. But that has nothing to do with reviewing. And the contrary is true on Broadway.

Michael Kantor: What’s changed since 1971 when Andrew Lloyd Webber brought Jesus Christ Superstar to New York?

Brendan Gill: Mr. Weber, now what is he, Lord Weber, or Viscount Weber, whatever he may be, in English nomenclature, did something to, and we consented to it, indeed we rejoiced in it, to transform theater, which is to take the musical comedy and turn it into a spectacle. And it’s a kind of Roman spectacle, it’s kind of circus spectacle, and it is absolutely bedazzling. And we just couldn’t. Get over the seemingly, the opulence, the number of people involved, the costumes, the excitement, and then his music, which I’m not an authority on music, but I’m told is largely a pastiche of other people’s music over the years. And then we had Cats now, the longest running play that a musical company has ever been on Broadway. And on and on and it went. But it was really truly a fact that it was the spectacle that beguiled us, and we found thrilling, and it was actually truly the case that we began to applaud the chandelier for falling in Phantom and the Opera. Or we applauded the poor sons of bitches in the Les Miserables who had to keep up with the turntable as they were singing, and again and again, or it was The Staircase in Sunset Boulevard, and of course it was a great finale of Cats where everybody descending. Into Cat Heaven. These things were astounding to watch and they have almost nothing to do with the kind of theater that we were developing under Rogers and Hammerstein in the past when we had these stories that had a story line and seemed to have something to do with ordinary human emotions. You’re not supposed to feel ordinary human motions in a spectacle, or indeed at the circus. You’re aghast with. Admiration and wonder, but you’re not moved in any Aristotelian sense to pity and terror internally. It’s all, it’s an optical wonder.

Michael Kantor: Give me a sense of the Broadway theaters architecturally, the range from the huge hippodrome to the music box.

Brendan Gill: It was one of the wonders of Broadway theater to be able to accommodate all range of size productions so that we have the smallest theater, little tiny theaters of 299 seats, like I think the John Golden is something like 399, something like that, up to what was then the biggest, when it was knocked down in the Hippodrome, where again, this was kind of Weber-like for its day because that was simply all spectacles. A dozen beauty diving, bathing beauties, diving into a pool in front of the stage and disappearing from sight and never coming up again until 15 minutes later. How was it done? Anyway, that had 5,922 seats, something like that, almost exactly the size of our musical, Radio City Music Hall. But the biggest legitimate theaters we have are for musical comedies, the Gershwin, things like that. I think around 2,800. But you have a range of a couple of thousand different things and the skill of the designer consisted in making everybody seem to be as close as possible. The Schubert’s always say you can’t sell the second balcony, but I don’t think they really want to sell the 2nd balcony. You can still, there are many theaters still left with the 2d balcony and Carnegie Hall is row after row of balconies going up like that. But the theater architecturally and Broadway architecturally has. It’s a wonderful palimpsest of architectural styles of what we have thought was sophisticated or dazzling or fantasy-like over the years from 1900 on. We have Moorish and Colonial, even Colonial and David Velasco’s theater pretended to be Colonial. That kind of thing. Every style, and some of them have adapted themselves very well. To amplification, but almost all of them were built with the intention that the human voice would suffice to carry to 1,500 to 1 ,200 people. And they could, and certainly Ethel Merman could carry to 15,000 people. But it is thrilling to me as a student of architecture that we have saved as much of Broadway as we have, and now by city law, nobody can knock down a theater. Without the permission of the city government. It isn’t pure real estate speculation that it was in the past. We lost several great theaters before the rules were put in. No, you can’t knock it down. We’ll find another use for it if necessary.

Michael Kantor: How is the Broadway musical a distinctly American art?

Brendan Gill: We claim that the Broadway musical is a distinctly American art form. And it is true that other countries have tried to imitate the kind of musical comedy that we have had here for the last century and have failed, largely have failed. And the secret appears to be, as far as I can tell, the amount of energy that we put into a musical comedy. The British, when they do a musical, they’re fairly lackadaisical. They dance like this. And we dance like mad people. And certainly since Agnes DeMille and other people like Ben, certainly from Oklahoma, the operetta, which was a European thing, was very delicate and nice, and they would have a waltz. But they wouldn’t have the vehemence, the power, and the control energy that we developed over the years. And then that’s one of the reasons that American ballet took off really from American musical theater to be much more. Much more vehement than it would ever have been in Europe. It ceased to be just thought to be tasteful. It was something in which the human body was really made to perform miracles. And that, of course, is what happened with the Bring into Noise, where we had the extreme of physical athleticism turned into art.

Michael Kantor: How do you go about describing Broadway?

Brendan Gill: First of all, you describe it as being, in physical terms, that it’s a very odd and wonderful shape. Indeed, it happens with the crisscross that you get what is Times Square, which is a kind of a butterfly. So you can either talk about Broadway, which really means theater and restaurant and nightlife and all that, or you can talk about Times Square which is more razzmatazz and a certain element of the tawdry of the chief of the circus in Times Square. But that is… They are linked, but not identical, but they are our village green. If New York City was to say it had a village green, then the profane village green of New York City is Times Square and Broadway, and the sacred would be, I suppose, St. Patrick’s Cathedral and maybe Rockefeller Center even, as being somehow loftier and more noble in concept. But we want Broadway and we want Times Square. And we fear continuously that in keeping Times Square alive that we will lose the honky-tonk quality because there’s a kind of, in spite of the Baptists and their disapproval of Disney, the fact is that Disney is more wholesome in its appearance on Broadway and on 42nd Street than anything that’s ever been there before. But… Oddly enough, had been there before that everybody was screaming and howling about it, all the ministers and priests and rabbis and so on, was going to vanish anyway. Pornography long since has left the public arena. It’s in the rumpus room in Scarsdale. It is the children. Forty percent of all the hardcore porn sold in the United States is sold for residential use. So it has nothing to do with Times Square and 42nd Street. That was 35 years ago. But in any event, Broadway represents a concentration of energy, a place where energy can be manifested with the lights, with the experience, with a sense that something is happening and happening continuously, and it has to be for 24 hours or it doesn’t count.

Michael Kantor: Is there any way to capture the excitement of Broadway theater on film, or do you have to be there?

Brendan Gill: I think that the film has the grave defect of being a machine, of being at odds with reality, which is the constant movement of our bodies as we go and going like this in time square. The collision of forces, always unexpected and unpredictable, is what makes part of the energy of Broadway Manifest. And of course I believe that about the theater, too, as contrasted to television and radio, and movies. That my belief, which is maybe a harsh one, is that the audience, the living audience in a legitimate theater and living actors performing on stage, that the bond that is established between them is a bond not only of our admiration for these highly skilled people performing at the top of their bent and how proud we are because they’re standing in for us. We couldn’t do anything like that. My other consideration is, however, We want them to fail, that there is something, that the bond consists not only of an exchange of energy on an affirmative level between the performers and the audience, but on a negative level between the performance and the audiences. The performers fear failing, and we want them on some awful level to fail. There are a certain number of people in any audience who would want Judy Garland to die on stage, who wanted Tallulah Bankhead to die on stage who wanted John Barrymore to die on stage. This is a terrible thing, but I’m convinced that it’s true. But true or false, the bond is an authentic one, back and forth. They talk about interactive in television as if television could somehow, and maybe it can for all I know, or with computers, become truly interactive between the home and the box. But we know that that’s what makes theater great, that the intense emotional intimacy between us in the audience and those people on stage. And they know it, and we know it.

Michael Kantor: What about Stephen Sondheim’s contribution to the history of musical theater and company in the concept musical? What did he do?

Brendan Gill: Steve Sondheim was the heir to the, as he always says himself, to Hammerstein and in fact therefore also to Porter with his interest in rhyme and word play and has spent now 40 years giving us the most remarkable things and he himself, like Porter, able to write both the words and the music. But I think he’s also been impatient with the structure of the ordinary musical comedy and his sought to move into a quasi-operatic level in which something could be uttered that was of a more powerful nature, would have the capability of moving us as an opera does. And this has been a big struggle, I think, for him because it isn’t necessarily the case that you can move from this form here, this particular shapely form here to this much larger and still make it a shapely form here. And his ambition is admirable, and the difficulty of doing it, I just hold up my hands like that to think. He’s one of my heroes, because he has been working his way through into different areas of composition and of thought, of emotion. And he’s not content to have been one of the most successful musical composers that we’ve ever had in the theater here, and all hail to him.