F6 I think the very first time I came to Los Angeles, I think I came to Los Angeles in nineteen. Thirty seven. 37, 38, what was the occasion, the occasion was an official visit.

M5 Uh.

M2 That my father ducked out of, but it was an official visit by invitation to Hollywood and those in the 30s they invited. People from foreign countries to come. As a matter of fact, there are some countries who sent the diplomats to Hollywood. The French government had a representative. And I think that the Russians want that. I mean, they had people who are official representatives nowadays. Most countries have a consul general, a consulate in Los Angeles, because it’s such a big city. But these were people who were sent specifically to Hollywood to represent their countries with the Hollywood studios. But we were invited to my family. My father and mother were invited to come to Los Angeles to visit the various studios.

F6 And they had, you know.

M1 And in those days, they didn’t have studio tours. I doubt that, but when they had invited, yes, they would take them on sets and we went on the sets with Rita Hayworth and Fred Astaire and Clark Gable and gosh, so, so many of the people, whoever was making were making films.

M2 And there that was I ran across a few of the old pictures of another were taken of myself and my sister and my mother with along with the stars of the day. But for me, it was the most interesting thing was meeting Fred Astaire because Fred Astaire was a sort of special. A special idol of mine for his. Nonchalant elegance and is a great style and to this choice of of clothes and and the way he wore them, there were two people in my youth who personified the elegance of the of the years between the wars. And there were the Duke of Windsor and the. And who is the prince of Wales originally and who have been, by the way, also to have been a jazz fan?

M1 He came and it was had him and and Fred Astaire, who both had a very personal.

M2 Style of dressing, of course, Fred Astaire also was a wonderful singer and probably one of the greatest dancers of the century. Jerome Robbins was one of our greatest choreographers, said to me that he thought that Fred Astaire was as good as dancers and a ballet dancer.

M1 He never ran across a. I took Baryshnikov to see the Rolling Stones quite accidentally, I ran into him in the hallway at a hotel in Washington and he asked me what I was doing. I said, why don’t you come with me? I’m going to see the Rolling Stones are playing tonight. And he came with me and and after the show, he said to Mick Jagger said, you know why? They said there are only two people in the world who can dance the way you do that says you and me.

F22 That’s wonderful.

F9 Well, when was the first time that you came here for the music business? For the music scene? For years.

F16 Oh, you see, in those years I came I came in in the in the 30s. Then I came here again in the not 39 or 40. I came quite a few times.

F1 And when I was going to college, I had to my best friend and in college with a boy, Dick Sullivan, whose grandfather was one of the people who was a pioneer to establish the state of California. And he owned a great part of the of the Los Angeles area. And and so I would come in the summer sometimes and just, you know, to visit Dick and and then we had other friends here. So I came to Los Angeles quite a bit. And in those days, well, we’d come here and that was my brother. And we spent quite a bit of time going to the local second hand record shops and looking for old jazz records they still collected out here.

F7 Oh, yes.

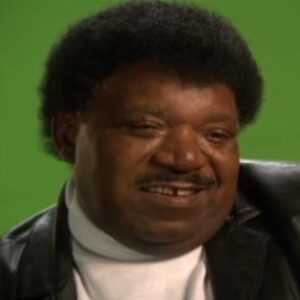

F8 Excuse me. Ray Charles is here. We do. OK, well, he’s been here all along. He’s got something to do in the studio. I’m sorry. No, it’s it’s totally known to us. You couldn’t miss it. I did. Way, way back anyhow.

F9 I was just wondering when you first came here for the music, this is what the music scene was like here when you first started, you know, coming here with the notion of as we started Atlantic Records well before I started the planning racket.

F1 Well, you know, when we came out here. The the the music that that we really liked in those days was New Orleans jazz, and it wasn’t the only jazz music we liked, but we like that, particularly because it was dying and kind of no longer really existing. And I know that we made a special trip to go to San Francisco to hear the year. But when a jazz band, which was a jazz band put together by some musicians who were also jazz scholars, they studied the music of King Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton, and they played that music. The trombone player was Derek Murphy, who became a fairly big name and in jazz. But and Bob Scoby was one of the trumpet players, was a great trumpet player. And there were some very good clarinet players that changed in that group. But it was a very, very exciting thing to walk into a hall and to hear a band playing just like King Oliver. Two trumpets, one playing lead like King Oliver, the second playing the heart. What they used to call the hot chorus is like little Louis Armstrong. And to have a revival of that in front of your eyes was incredible because they really were very authentic reproductions of that music and the records that are still around there. There are wonderful records. And then we we listen to people like, you know, who are still around guitar. He was here and Jimmy Newton and some of the great clarinet players were in California at the time. But I was I was fired in those days from I really was not thinking at all in terms of a record business where we were jazz fans and and we were strictly and very, very, in a way, a religiously adhere to only real jazz and not pay much attention to pop music, but that in order to hear jazz, we had to listen to a lot of pop music anyway. So we became expert on that style of music as well. But our love with jazz and.

M2 NASA eventually moved to California while I was still in Washington and and he married a girl who owned the jazz records and a jazz band record shop and and eventually taught courses at UCLA on the history of jazz. And I think he was the first one who gave courses for credit at a major American university about jazz music. That was in the middle and late 40s. I started The Atlantic. Without much regard to what was going on in California, because that was much too far away for us to to think about, we we we we were a small company with a very small capitalization, and we couldn’t afford to travel very far out of New York in any direction.

F3 And but somehow.

M2 The first artist that we got from the West Coast was Ray Charles, because even though he wasn’t born here, Ray Charles. First made his first records in California for the springtime labor, and that’s when I first heard Ray Charles.

F4 And was that you remember what the first song was you heard of?

F2 It was called Baby, let me hold your hand.

F4 And when you heard it, did you what was your reaction?

F1 My reaction was why on earth can’t we find artists to sing like this? Was it was just I was absolutely.

F5 Knocked out.

F2 He was just an artist who.

F16 For me.

F1 Had the attributes. Of all the great singers I loved, I mean, he had he had he was a combination of all my favorite singers and and he was well, you know, and those days I really like Nat Cole. I like Charles Brown. I like Lowell Fulsom, I like a lot of well, he had a lot of everybody, as a matter of fact.

F6 He was distinctly himself. But in him, I could see traces of different people, but it was always Ray Charles.

F7 When you wrote Mizoram, did you write it specifically with Ray in mind?

F5 Oh, yes, I only wrote I wrote it for a particular session and it was really.

M2 Inspired by some of the early. Early boogie woogie records that I had heard when I first started to collect those blues records. It’s inspired by by. The music of Pinetop Smith and Colquhoun, Davenport and. And cripple Clarence Lofton, often these names may not mean much to you, but criminal Clarence Loftin was one of the great boogie woogie piano players and. He wrote this, he wrote, well, he made several records which were minor, minor and big hits in the Chicago area and.

F2 But between credible Clarance and the cow cow Davenport, you know that the the piano part, and that is straight out of cow cow Davenport cow blues and and some of the lyrics are similar to so Pinetop Smith lyrics.

F1 It’s it’s an outgrowth of of traditional R and B music.

F2 Boogie woogie and blues had a deep tradition of a certain left hand that left left hand bass parts and. And this incorporates most of that.

F7 No, I did you show this part or was he familiar?

F1 Well, I have the time and I mean, he picked it up right away. You know, he’s just yet just have to say very little of it was right. He gets it. Whether he ever remembers it actually remembers that he has a. He has a subconscious memory of all the music that went on before him. So, I mean, for him every. Everything that was ever played is a reference here. He remembers everything you have heard and he’s heard a lot of music, I’ll say.

F8 Really? That’s interesting. It’s good to talk for a couple of things before he’s here. I think you’d be more comfortable saying about him in the room. One of the things that I wanted to mention also was the scene of the LP, The Genius of Soul, that the genius of Ray Charles, the genius of Ray Charles, that that was produced by you all.

F7 And I guess was this your brothers?

F1 Yes. Natsui was the lead producer of the genius of Ray Charles.

F5 He.

F1 He picked the he picked the the band and the arrangers and I worked with Ray and it was a it was a momentous session where the the musicians all applauded after each take when they whenever they played something bad because they were in such I mean that many of them had never really heard Ray Charles the way he was on that session and what he was actually quite unknown compared to the cast of characters on that session.

F7 It’s quite a it’s quite a session.

F1 Yeah, there were a lot of. You want me to tell you? Well, I mean, well, Quincy was a lead arranger. There are also some arrangements by I’m just trying to think the entire company back. Yeah, man.

F10 A lot of the Ellington members who were in the band, it was a big band and and they really swing on some of it.

F1 And, you know, as Ray is doing, because Ray has a knack. I mean, he will hear like the third trumpet is a plane flight, you know, on the edge of the six bar and so forth. And he he knows exactly what was going on and what’s wrong.

F11 So and of course, he he says the beat and he sets the the feel, which is the most important thing.

F12 You know, it’s it’s on and it’s on records. I let the good times roll or what I say. I mean the feel is what really gets makes makes that kind of a song.

F10 And and he knows how to get to get in the proper pocket and and and to make it and to make it swing. As few people knew how to make things when Mr. Armstrong was one of them. Mr. George is another.

F9 You know, one of the things that I thought was interesting in reading about this release, it seemed to me it’s obvious, but this that that that LP seemed to be a an early culmination of fusion, shall I say, of the interest that you and your brother had in music.

F7 And I guess that’s what I was sort of trying to get you to sort of talk about this idea of the R&D and jazz being used.

F11 Yes, but she was Ray Charles Ray’s music is, as you know, incorporates many, many, many stars and many things, as I said he has, and an incredible frame of reference. And one of his great attributes is that he’s a terrific jazz musician and. And he’s able to to develop his feel for jazz by making a big band like that swing out to make it feel in a good groove. He is. Well, it’s it’s I know he’s a he’s a grand master and at what he does and and there aren’t many, if any, whom you could really compare him with.

F14 And in that way, I think that the NSA nationally recognized how how important it would be to acquire them in a jazz groove and.

F11 And the genius is, again, a combination of many styles. Soon thereafter is when Ray went into a completely different mode genre of music, when he started the record country music with big bands showing again that his. Musicality extends beyond classification.

F4 It’s a good way to put it, when you were opening the doors to Atlantic Records, it just sort of occurred to me, why didn’t you go to a place like why did you go to New York instead of places like Chicago?

F14 Well, frankly, I lived in Washington as the only person I really knew well, who was a friend of mine who had been in the record business with Herb Abrams and with whom? I decided to become partners. At.

F15 And Chicago seemed very far away, and I knew nobody there now, I knew that the that the blues players were out there, but I didn’t know how deeply they were out there. Because I thought that in New York we could find anything we’d find in Detroit or Chicago, but that wasn’t the case. And New York. And Harlem was a very sophisticated place, which, in a way, Harlem rejected country blues and. But the country blues players found home in the Midwestern cities and the Texas blues players found a home in California.

F4 So how did you come up with the name Atlantic Records?

F15 It was like our 10th choicer, 10th of 15th, because every every name we came up with was somehow taken or blocked or, you know, the name that we thought that was was going to be accepted. But Horizon and our first. Our first. Correspondent I see in some of the early early were quiet horizon records, but then apparently there’s but then another company that’s been taking that name. So we settled on Atlantic. Since we were on the Atlantic coast, I mean, that’s about as.

F4 When you opened your doors for The Atlantic with Atlantic Records, did you think that you were gambling?

F11 Well, I thought I I thought that we had a small chance of survival because even though there’s one thing I knew, I knew that we knew the music better than our competitors, we understood.

F14 What made people buy records? The kind of music we we wanted to make. And and we love that music.

F11 We love that we understood it, we knew it. We also knew jazz, but we weren’t going to be a boutique jazz label. We wanted to be a commercial label that sold all kinds of music, but especially music made by black artists for the black market and which is the music we like both most and.

F1 To the extent that so many small companies went out of business, that. There was you know, most people thought, well, that, you know, that we wouldn’t last very long and and they’re probably right and thinking that except that the records we made from the very beginning found a market and and the first year we sold enough records to survive. But I used to have these nightmares where I would wonder because I never met a person who had ever bought an Atlantic record. What? I never met a person who had ever bought an Atlantic record.

F16 And and, you know, I used to think, I wonder who buys it. I mean, we’re selling these records. So I got a record shop and said, stand there for hours. I see people coming by and they’re not buying it for their grandkids. So I just, you know, eventually I, I would wander into a record shop and see somebody go out and buy a record if we had something of a little bit of a that, you know, but.

F12 Whatever it was, the first request we made were not very great. I don’t think there were there were any masterpieces there. I think the best is that we made in those early years were the ones we had with Errol Garner. And but we we made some good records with Johnny Griffin, but some good rags with a tiny grymes. The most instrumentals, our first vocal, big vocal hit was with a blues singer that we locked up on Namers Stake. McGee Metters, a regular car drinking wine, reality set, sold a few million. And then we had a string of we started a string of smaller hits with singers like Al Hebler and Laverne Baker, Ruth Brown, the Big Joe, Tammy Faye. Gosh, you know, Chuck, well, you know, a lot a lot of when suddenly got a lot of young singers and so forth who were and we saw what they’re also some. And we got an occasional hit and we managed to stay in business and the company grew. And our first real crossover big stars were Ray Charles and then Bobby Darin.

F17 And Ruth Brown had a couple of smaller hits.

F18 Then we had no wasn’t big.

F17 And that whole crew and the people from Stax by Otis Redding was a major, major, big star and. And we continued that way and and we continue to make records and our and our style and. As they in the 1960s, we started to record a lot of rock and rollers and expand, expand our markets.

F19 No, I just want to sit with you, but I can’t I can’t ask you this in front of me, but I was I was very struck by various things about how you felt when after, um. The genius of Ray Charles, that you discovered that he had left Atlantic to go to ABC. You talk a little bit about that before he you start with him.

F20 Well, frankly, you know, there’s so many different accounts of how that happened is I think is unimportant because it happened and at the time it was very painful because. More than anything, Ray Charles was somehow had become not only, you know, associated with Atlantic A as a you know, as a leader and in in the new music, but. He had become a very close friend, and we still are great friends. All I remember is that we’d heard that there had been there were rumors that he was there was a contract that was signed. But another label and but I got a call from Ray Charles, I was in New Orleans saying he was coming up to record. In the next week, I said, well, we heard this other thing, and he didn’t seem to know anything about that at the time, but.

F21 There are other other accounts of that I’m not interested in, and you said something very funny, though, once you said, you know, about the relationship between a, um, I give you a way out of this relationship between a a. Record company and an artist is like a marriage. Do you remember what you said? No, I’ll tell it to you, then you can give it back to me. You said either someone find someone who’s richer or younger.

F22 So I’ll give you your words to give you back your story and you can get out of this very gracefully. Yeah. How did you feel about Charles leaving you? Well, you want me. Excuse me. Give me give me the anecdote about. It’s like a marriage. Don’t you have that on tape? No, I have it in the book you said it. Oh, I see. But I liked it so much it made me laugh. And I thought it would be good for you to say. Yeah, I guess that.

M4 That contract between record companies and artists, in a sense, is like a marriage because you get to know each other, you work together and you become part of the same thing.

M2 It usually breaks up because one of the parties finds either somebody who is younger or somebody who is much richer. And that’s probably what happened.

F23 Thank you.

F7 I thought it was very funny, um, I wanted to, um, you know, in your whole I have lots of questions, but I don’t have a lot of time. So, you know, in all the things that we talked about. I haven’t found anything that has been your life seems charmed to me. It seems like there’s been no conflict that hasn’t been momentary or overcome, and I’m wondering if that’s true.

F19 What challenges do you feel that you’ve been facing all this time that have been difficult, you know, some kind of real effort that’s not effort, but what challenges or conflicts?

M4 Well, we have, you know, constant challenges. I mean, in running a record company, you know, it’s a it’s very it’s a very, very difficult thing because it’s a business where you have to create your product over and over again. You know, if you make if you make a great automobile tire, you know, all you have to do is slight improvements or whatever, but keep it up to date, whatever. But but it’s the same product, the toothpaste, the same toothpaste. Maybe you change you change the flavor a little bit or you advertise that it removes cavities or whatever. But basically it’s in the record business. We can sell Atlantic Records. We have to sell a record by selling a particular song by a particular artist. And that has to be changed all the time. So we have to make our product over and over again and we don’t have to make a new product, but we have to promote it and publicize it, advertise and sell it. And it’s a tough it’s a tough business that it doesn’t stop. And they have today I you know, I open up Billboard magazine and I see that we don’t have that many on the top 20. And and and you think about what have we got coming up and how are we going to survive? And they have this very tough market, you know, that we managed to do that through with different but different executives. I’ve had a changing roster of executives, but right now I think we’re in a good situation. But you can never tell we have other problems now. We have the problems of trying to sell. They’re trying to sell something that people can get for nothing. So that’s very difficult.