Speaker Everybody right? Yes, for you. Thanks. OK. We’re just going to identify the tape. This is Saturday, May the 10th.

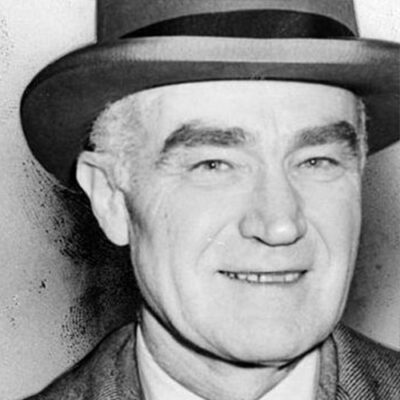

Speaker This is American Masters, Henry Luce Project Penn. We are. This is first tape of our interview with Alan Brinkley. I’m going to get specific.

Speaker In a minute, but.

Speaker First, I want to ask a couple of general questions about Libya, since publication was covering one of the things that I think about and I’m sure you’ve read into this, if you’ve talked to any younger people about this.

Speaker People I know who Henry Luce, it’s even people 40 years old don’t know who he is. What do you think would be the most important thing for a film like this to convey about him and about who he was?

Speaker Well, I think the most important thing about Henry Luce to most Americans is the way in which he created new forms of media that help shape the kind of media world we live in today in which he and the way he envisioned creating magazines that would reach out to a truly mass market, truly national market. The way he envisioned creating a bridge between high culture and mass middle class culture and the way he thought about how you package knowledge in a in a modern era when people don’t have the time and the leisure that they once had had to absorb knowledge and more more casual or more leisurely ways. Luce was a great sort of repackaged air of information. And in the information age, I think that’s that’s a significant thing to remember about him.

Speaker But his efforts are peacefully policing. Car.

Speaker She’d go off shorefront. Yeah. Good.

Speaker What importance do you think that Luce had in the American cultural and political landscape?

Speaker Well, I’m not sure Luce personally had a huge impact on American culture, but the magazine certainly did, and the magazines were an expression of his vision to some degree. I think what he helped to do in the 20s, in the 30s in particular, was to create. Or to contribute to the creation of a genuine, genuinely national middle class culture. And what he what he added to what the movies were doing, radio was doing with other new vehicles and mass communication we’re doing. He added a picture of the world, a way in which people could learn about what was happening not only all across the United States, but all over the world in succinct form, almost digest form by week after week. This was the window on the world for many people, the United States, who did not have access to good newspapers and for whom there were no other vehicles for learning about what was going on in the world. Radio didn’t have very much news. There course was not yet to tell. Television movies had newsreels, which were mostly entertainment. This was it for many Americans. This was how they learned about the rest of the world.

Speaker Did you read that part of your sort of household Life magazine was the first magazine I ever had a subscription to, ever had a subscription of my own, too?

Speaker And my parents got it for me when I was about 10 years old and I used to keep them stacked up on my bookshelves. I think that was characteristic of many people’s, many young people. This was in the late 50s, early 60s, when life was still extremely powerful and extremely popular.

Speaker What was it about life that you liked as a young person?

Speaker I think what I liked about life was the variety, the enormous.

Speaker Enormously varied. Ways in which it took an interest in the world. But I also liked it because everyone else read it and people talked about it and it made me feel part of the national conversation.

Speaker What about it?

Speaker Actually, you know, and we talked about this when we got together a while back, but there there is sort of a segment of the population of the time readership that had kind of this love hate relationship to it. Can you describe what that was about?

Speaker Well, I’ve certainly noticed when I talk about Luce and Time magazine in front of audiences that there are always people in the audience, especially older people, somewhat older than me. Who will stand up at some point and say. My mother would not allow that magazine in the house. It would arrive in the mail and she’d throw it in the trash. And, you know, how can you talk about loose and not talk about the incredible bias in his magazines? And yet you listen to them for a while. You realize they all got TIME magazine. They continue to subscribe to it. They probably did read it. But it infuriated them. And I think this was particularly true in the 50s. That was the period in which time was the most overtly Republican and liberals and Democrats just were infuriated by it. And yet they felt they had to read it. There was something very seductive about it, even at the same time that it was infuriating to them.

Speaker What was what was Harry Luce like? What was he? I mean, what would you. How would you describe his?

Speaker Personal credo or his beliefs? What were most important to him?

Speaker Well, I think the first thing you have to remember about Loose Eye is that he was the son of a missionary. I think that’s the single most important thing about him, that he grew up in China in a missionary community. And he absorbed it from his earliest days, the kind of. Social crusading missionary impulse with his father had that the people who grew up with had, and I think that shaped him in very profound ways all through his life, that he never thought of what he was doing simply as a business or simply as journalism. There was always a sense of mission. In what he was doing and when he went into journalism, when he chose not to become a missionary like his father. He justified it both to his father and I think also to himself by saying this was a different kind of mission.

Speaker This was a different way of shaping and improving the world. And I think there always had to be in his mind, there always had to be some kind of higher purpose in what he was doing. Now, sometimes, you know his. Vision of what his higher purpose was was completely disingenuous. It was just something he made up to justify to himself things he wanted to do. But I don’t think it was hypocritical. I think he really did believe that he had an obligation to do something valuable for the world. Now, whether we think what he did actually was valuable for the world is another question. But he thought it was and wanted it to be.

Speaker Tell us about his childhood children and his growing up. What? What it was like. For their family, where they will love to see the hardship, what could have been worse? It wasn’t that he was.

Speaker Luce’s family was, in fact, by the standards of middle class America, quite poor.

Speaker They had no real money of their own. Like all missionaries, they lived on the generosity of donors in the United States. Neither of his parents had wealthy families, prosperous middle class families, but not wealthy. They were cut off pretty much from all of their financial contacts in the United States.

Speaker So they lived in whatever way the donors to the missionary enterprise allowed them to live. Now, Henry Winters’ loose Harry’s father. It was a very prominent figure among American missionaries in China and among other things, was one of the most successful fund raisers among missionaries. He was always going back to the United States for these grueling fundraising trips. And one of the things that made him successful is that he was very good at. Ingratiating himself with wealthy people who were interested in the missionary movement and when the byproducts of that is that a number of these people contributed money for the Lewis family.

Speaker So even though the losers had no real money of their own, they lived quite well in China, at least by the standards of missionaries, after a certain point, they lived in a house that had been built for them with money that was provided by. Remember the McCormick family, Nettie McCormick in Chicago. They had an income that was provided by her and by others.

Speaker So they lived a relatively comfortable Victorian Middle-Class Life there in the middle of China. They had house servants. They ordered things from the United States, from the serious catalog in huge lots. Once a year. Always having to calculate how much the children would have grown in the eight months between when they place the order and when the stuff arrived. They lived like most middle class people. It’s just that they were living in a missionary compound instead of a. Suburban area, middle class area in the United States.

Speaker What was his how was he raised? What kind of.

Speaker But, you know, environment in the household as well. Well, more to the point, was his relationship with his parents, Luce’s parents were absolutely in thrall to him from the moment he was born.

Speaker They and they had three other children whom they also loved very much. But Harry was always the one that they considered the most important. And partly because he was the eldest, partly because he was a boy and at least his next two siblings were girls, but also because they they thought any way that they saw in him from a very early age, a kind of brilliance that that they considered quite remarkable. And they were they were throughout their lives. The people who always believed that Harry was destined to be a great man in the household in which he grew up, was an unusually close knit one, in part because there they were in China. Know, apart from. Very much larger community. There are other missionary families in their compound, but not very many. So they learned to be each other’s best friends. And it was an extraordinary family life that they had. You know, they read to each other. They played music. They spent summers together in the seaside. They. They were they until Harry was 10 years old and went off to boarding school, his mother taught him at home and his mother and father. And she continued to teach your sisters at home for sometime after that. Once they were apart, they wrote letters constantly, sometimes every day, and kept their family alive through correspondence for many years. It was a very close and loving family. And like all families, there were sometimes tensions. But you don’t sense in the least in the record that we have of these years that there was very much tension. I think the unhappiest they ever were as a family. Was when Harry was sent off to boarding school in China to British boarding school in China when he was 10 years old. Because there were no schools anywhere near where he lived and he hated it. And he was desperately homesick and he was not treated very well. It was a very severe British boarding school and they didn’t really like Americans very much. And he wrote these. Desperate letters back to his parents, please let me come home. What have I done? Why have you sent me here? And you can only imagine in the letters that his parents wrote back. I don’t. I’ve never been able to find. I can only imagine the anguish that this must have created in their home, and in fact, at one point they did bring him home for a term because he was so miserable. But they knew that they couldn’t educate him adequately at home and they sent him back. He remembered those years for the rest of his life as years of incredible loneliness. And eventually he developed a kind of retrospective affection for the place. But when he was there, he just despised it. And yet he compensated, I think, for his misery by developing a characteristic that was that he retained for the rest of his life, which was to become. The world’s greatest achiever, and if he was gonna be at the school, he was going to be the best in everything. He was going to do everything. He was going to run everything. And to a large degree. He did that.

Speaker What? Well, actually, if you could just say, because I think a bus hammered it. The wonderful thing you said at the beginning about the time for his parents were enthral. Here, if you could just see that one more time.

Speaker Well, from the moment Harry was born, his parents were in complete thrall to him. They saw in him even as a baby, they imagined in him even as a baby, a kind of brilliance that, in fact, he turned out to have as he grew older. And although they loved all their other children, I think Harry was.

Speaker It’s clearly their favorite. The one whom they invested the most hopes. He was the oldest. He was a boy. But also he he had, at least in their eyes, some kind of special quality. That, again, I think they first imagined. But eventually he seemed to develop and perhaps their faith in him was one reason he did develop it so successfully.

Speaker Mean.

Speaker What kind of man was his father?

Speaker Well, Henry, winter’s loose. Harry’s father was.

Speaker From all I can tell about him, a wonderful man.

Speaker He was a missionary. And was one of these people of his generation who was drawn into the student volunteer movement. The great student movement of the late 19th century that attracted so many young people into.

Speaker Let’s just settle. And Mark, you know what? You just took a look at your mike.

Speaker OK, sure thing.

Speaker Henry Winter’s loose. Harry’s father was a really remarkable man. He was part of a tremendous student movement in the late 19th century of young people who were attracted to the missionary project of of these years. And so he became Presbyterian ministry, became a missionary. He married a very religious young woman. He took her to China. And Harry was born shortly after they arrived. But there were missionaries and there were missionaries and. And. Harry’s father, Henry W Luce, was, at least in my view of the world. A particularly attractive kind of missionary. He was not. He was not so interested in imposing Christianity on the Chinese people. It was his project in China was not so much to convert people to Christianity, although that certainly was something he hoped for. He really saw the mission of the missionary. As one of kind of social uplift. And yes, he you certainly believe that the Western model was the model that China should follow and that America was the prototype for a modern, successful society. But most of what he did in China was not imperialistic. Most of what he did in China was to try to help the Chinese people to improve their society. And he lived through during most of his years in China and in one of these desperately poor regions of China’s, Shandong should have been devastated by famines. And he taught school he was a school teacher. Basically, during these years, he worked in these little Christian colleges where Chinese students would come to learn physics and math and tools that they could use to better themselves and better, better China. He was very tolerant of Chinese religion, very interested in it. He would sometimes walk through through the mountains to get to the Chinese shrines where Chinese clothing. He was, you know, in some ways not at all a cultural relativist, but in other ways he was he he really did respect Chinese culture. And in his relations with his children and particularly in his relations with his son.

Speaker He was, you know.

Speaker Extraordinary father. He he was someone who really tried to understand what his son was thinking. He offered advice. I was not not bullying advice, but genuinely warm and heartfelt advice. There was an extraordinary relationship between them. I think his father was the most important person in Harry’s life. And their relationship was. Extraordinarily powerful one for him and his for what his father thought of him was extremely important to him. And his his father, of course, tremendously admired him, was extremely supportive of him. But of course, every now and then offered advice, maybe you shouldn’t do this. Maybe you shouldn’t do that. Harry. Take that advice extremely seriously.

Speaker Where did Harry come by his. His image of America. I mean, he was.

Speaker Really, I think what was it was eight years old the first time he set foot in the US, that he didn’t really come here until he went to Hotchkiss.

Speaker How did he. What? What was his image of American? How did he come to have.

Speaker Well, he didn’t really live in America until he was 15 years old and he did make one trip to United States when he was eight. But otherwise, his entire childhood was spent in China. And so his image of America came from a few places. I think the most important source of his image of America was the image of America that the American missionaries embraced as they attempted to export the American model to China. And to them, America was at least America, the America they conveyed to the people around them was a kind of shining model of modern democratic life. And that’s what it became to Harry.

Speaker And I don’t think he ever abandoned that view of the United States. His first image of America was not as a real place. It was a as an ideal, as a model to which other peoples should aspire. You know, in many ways. His image of America was the image that.

Speaker At its best, America had two non Americans around the world in the late 19th century, as is the great democratic nation that stood as an alternative to the more heavy handed imperial nations of its time. I mean, never mind that America was becoming an imperial nation itself. That’s not the way Americans saw themselves in China. And it’s certainly not the way we saw America.

Speaker How did he come to stutter and how does that affect life?

Speaker I don’t think anyone knows how people develop stutters. His family had all sorts of theories about why he had his tonsils removed and he came out of the anesthesia too early. I don’t really believe that’s what caused stuttering. I don’t really know how it came about. I know it was a very painful thing for him as a child. And he struggled to overcome it. In an extraordinary way, I mean, for example, he always wanted to be on the debating team wherever he was. And you would think that would be the last thing that somebody with a stammer would want to do. But it was a way of testing himself. And when he left China finally to go back to the United States, go to Hotchkiss. He spent a year in Europe on the way. This itself quite a story, this 14 year old kid traveling alone around Europe for much of a year. And during a lot of that time, he went and he stayed in a in a private school, a boys school in England and in the English countryside. And the headmaster of the school was supposed to be a renowned speech therapist. I mean, go figure. And so Harry lived at the school. He didn’t attend the school, but he lived at the school and he did speech therapy with this guy. Now, his letters at the time. Suggest that the speech therapy was completely useless. And he he liked the man. But he never felt when he wrote to his parents, he never suggested that anything that was happening at the speech therapy was helping his stammering at all. But nevertheless, by the time he got to Hotchkiss, the stammering was mostly gone. And how it went? I don’t know. I mean, it may be that this man was a more effective therapist than than Harry admitted. It may be that he found a way of his own to overcome it. There was always a little bit of it all through his life. If you even if you see films of him very late in his life, you can if you know, you can sort of see the signs of a stutterer still there. Halting kind of speech that he sometimes used to avert trouble.

Speaker But he.

Speaker He was very proud of having overcome this. And one of the evidence of that was that he loved public speaking or at least he insisted on doing a lot of it, gave speeches all the time. He went out of his way to find opportunities to give speeches. And I’ve always thought because he was a very busy man. And it can’t have been easy traveling all over, giving speeches at the same time that he was running a publishing empire. I’ve always thought he did that to prove to himself that he could do it, that he was good at it. He wasn’t, in fact, a particularly good public speaker. He was adequate. He was all interesting things to say. But he was not really a good public speaker. But he wasn’t.

Speaker A bad one. And he could do it. And I think that’s what really attracted him to. To X-ray.

Speaker It’s really amazing. I see things when I see some of these films of him and.

Speaker You know what he says. If you read, it is very powerful. But his delivery is really very good. He’s got that sort of halting nasal voice.

Speaker Well, he and he’s his delivery was you know, he would race through his speeches. And then every now and then, there’d be an inexplicable pause. And it really wasn’t a very. Appealing, speaking style. But, you know, he got through it. And, of course, he was a famous man. People want to see him. They liked what he said. However, he delivered it. So he thought of himself as a great speaker. He really wasn’t. But he was a much better speaker than you would imagine someone who grew up with a stutter could ever be.

Speaker When he finally came to this country. One or two. When he finally came to this country. And began to experience it.

Speaker How did it measure up?

Speaker Well, you would think that when someone who had never lived in the United States and had idealized it in the way that Harry did and when he finally arrived to this contentious, complicated country, as it was in the early 20th centuries, of course, it still is with. You know, its highs and its lows, its wealthy, it’s poor, it’s conflicts, it’s you would think it would be a very jarring experience, but you have to remember what he arrived here to do. He came to the United States and he went up to. Connecticut to rural Connecticut, to Hotchkiss School to this bastion of the wealthy and privileged. This idea like little country town. And that’s where he spent the next three years. And when he wasn’t in school, he was visiting relatives who lived on farms or lived in small towns or he was visiting friends from school who were much wealthier than he was. So he was in America for a long time before he really began to see very much of America beyond the world of the upper middle class and the aristocracy. And, of course, it was always that world, the world of the high upper middle class and the aristocracy that he mainly inhabited. So I don’t think there was ever any disillusionment with America. There were things he saw about America that you didn’t like over time.

Speaker But he never lost that deep faith in what America really meant, really, and what he thought it really was that he’d absorbed in trying to. When he was a child.

Speaker What was it like adjusting to what was it like for him in Hotchkiss, adjusting to.

Speaker Harry liked Hotchkiss. And almost from the beginning talked about what a great place it was. But it it must have been very hard for him. First of all, he was a scholarship student. And I this is a very class bound environment. And scholarship students were stigmatized and all sorts of ways. They couldn’t live in the dorms.

Speaker They had to live in boarding houses and start over there because this was the part about 30, faucett 32. Let’s change. Okay.

Speaker Well, we were getting ready to do this. We lost.

Speaker Harry. He wrote Harry in 10. Tom Griffith.

Speaker He was an old friend of my mother’s, a lovely man. Really nice. Everybody says this is the sweetest thing we have to meet.

Speaker So, again, let’s talk about his life as a scholarship student.

Speaker Well, Harry always expressed great affection for Hotchkiss, but it must have been a very hard place for him when he arrived because he was a scholarship student and this was a very class bound school. He wasn’t allowed to live in the dorms. He had to live in boarding houses and Garretts over faculty houses. He had to work in the library, had to wait tables. There were all sorts of little stigmatizing events in his life there that were unnecessary, obviously. And I think were insisted upon by the imperious headmaster of the school to remind these scholarship children that they were, in fact, being denigrate favor by being allowed to come to the school. And they weren’t in the same social category as everyone else.

Speaker And yet.

Speaker Harry. With you know what? Even at that age was very characteristic determination set out to, in effect, conquer Hotchkiss. And he wanted to be the best student at Hotchkiss. And to a large degree, he was he wanted to be the most prominent figure among the students. And he was certainly one of them that the literary magazine. He was on the debating team. He won the Greek prize. He Emmy, he was an extraordinary success there.

Speaker And I think.

Speaker He was certainly aware of the way in which scholarship students were treated, but because. His penurious illness was a result not of. Inadequate social background. His father had been a Yale graduate who’s from a prosperous middle class family. But because of the choice that they’d made, because his father was a missionary, because he’d made a moral choice to do something different. I think he felt that he was entitled to be part of the upper middle class, even of the aristocracy, even though financially he couldn’t be.

Speaker So how did he strike up his relationship with Brit Harvey and what was the you know, these two guys come to be friends?

Speaker Well, Brit Hadden, I think, was after his father, the most important person in his life in the whole course of his life. They met fairly early when they were toge guests, but they didn’t become friends for a while. Luce’s letters home in the first year or so that he was in Hotchkiss. I think there was one mention of Britt Hatton just in passing and I’m sorry. Looses letters home. In his first year, so it Hotchkiss mentioned hadn’t I think, just once just in passing. So I don’t know how they actually first came to meet each other or to get to know each other. Obviously, it’s a small school. Everybody knew each other, but they both became big man on campus. Hayden became the editor of the newspaper. Harry became editor of the literary magazine. They both worked on the newspaper. They were from the very beginning. Both friends and rivals. And that was always true of them. But I think they recognized in each other both the qualities that they had in themselves and also. Each side on the other qualities that complemented the other, and so there was a kind of partnership between them, a kind of unstated partnership between them. Even in these early years at Hotchkiss, they worked together on the newspaper at Yale. They worked to they were you know, Britt was the chairman of the Daily News and Harry was the managing editor. And they were you know, each of them had people they liked better. Each of them had better friends, but they were each other’s most important partners from a very early age. And it took them a long time before they really understood that themselves. But it started very early.

Speaker What was Brit had and like Brit was.

Speaker Completely different from Harry, at least on the surface. Harry was serious and sober and a little bit shy, and Hayden was a kind of a slap on the back guy. And, you know, always joking, always. He was the most popular guy on campus. He was a charismatic figure. People just flocked to him. He was truly an American in his own behavior and thought. And Harry, although he is devoted to America, was a little bit of an outsider who didn’t know, at least at first, you know, the slang. He didn’t know the jokes. I didn’t know the idiom and hadn’t grown up playing baseball in Brooklyn. I was, you know, the American man Harry wanted to be. And, you know, from the time they met until Hayden’s death, Harry was a necessary person to hadn’t and vice versa. But in their relationships with another, Hayden was always a little bit more prominent than Harry. He was the chairman of the Daily News. Not Harry. He was the editor of Time magazine. Not Harry. Harry did the business stuff. I don’t think he could have done any of this without Harry and Harry, at least. I think Harry probably could have done it without Brett to some degree and did, of course, in later years. But they were very important to each other. And yet there was also a kind of competitive quality. And they had fights and, you know, never real falling outs, but they were at each other’s throats at times. But that didn’t damage the underlying relationship, which was an incredibly intense relationship, not necessarily a loving relationship, but a really important one to both of them.

Speaker Did they have.

Speaker How did happen and roofs when they got to Yale?

Speaker It’s claimed that they revamped the.

Speaker And I’m going to let you pour your water and have it be well hidden and loose, took over the Daily News under very unusual circumstances because, of course, they.

Speaker They arrived at Yale during World War One. And during their second year at Yale, America entered World War One. Actually, during their first year, Yale, America entered World War One. And so the whole campus was turned upside down by the war. Slowly and. While they were sophomores, they took over the Daily News because everybody else had left. Well, the upperclassmen had left to go off to war. And so they took over the news early. And it’s often said that they revamped the Daily News. I don’t think that’s really quite true. I think they adapted the Daily News to this fundamentally changed character of Yale. As the war progressed, they made the news, first of all, much more attentive to. National and global news. They reported on the war. They reported in Washington, they reported on things outside of Yale. They also made the news. The. Voice of Yale commitment to the war, and they you know, just as in earlier years, people would write editorials exhorting students to support the football team. They were writing editorials exhorting students to join the ROTC or the officers training programs at Yale and to support the war effort. So I think they they saw the Daily News as a vehicle. For. Promoting the war at Yale and for drawing you into a commitment to the war. I don’t think that had a long term impact on the newspaper, but I think the one thing that did have a long term impact on the newspaper was their introduction into it of a commitment to covering news outside of the university.

Speaker Speaking of the war.

Speaker How did. Harry Sted. That this was a training camp in South Carolina. How did that affect his?

Speaker His thoughts about doing a man’s.

Speaker Well, this is the founding the founding myth of Time magazine is that Harry and Brit were at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, training troops for the war. They were Yale men. They’d gone through this officer training program at Yale and they were sent down to take these lumps of clay. Is the army solve these rural kids from the south who were drafted into the army and turn them into soldiers. And so the myth, I think, and I think it is a myth about TIME magazine, is that they spent this time trying to educate these kids from the rural south. And they realized that. These kids should know anything about the world. And that somehow they need to create a vehicle so that people like them could learn about the world, and that’s where the idea for Time magazine came from. I don’t doubt that Aryan Brit talked about the magazine when they were at Fort Jackson. They had been talking about it even when they were at Yale.

Speaker But I don’t believe this story. When they did found Time magazine, the kind of people who were drafted in the Army in South Carolina were not the kind of people they were thinking of. They used to talk about TIME magazine as the place that the busy businessmen and the tired Debbie debutante could go to get their news. They certainly didn’t envision it as a vehicle for. You know, poor rural farmers in South Carolina. So.

Speaker So when do you think let’s go back a little bit then? Well, what is your sense of when this the germination of this of this idea for a magazine, national magazine?

Speaker Well, they herion. Brit started talking about starting for a long time. We just call it a paper. You called it a paper and it wasn’t clear. Maybe even even up to not even to them whether the paper was going to be a magazine or a newspaper or something else. But they wanted to publish something. They wanted to create something. And working on the Hotchkiss paper and on the Daily News really instilled in them this idea that they could do it, they could run a publication. And it isn’t clear there’s no real record as to when they first came up with the idea of creating a kind of digest of the news, which is what TIME magazine began as. But from a pretty early point, that was the idea that they would create a publication that would present the news in a concise. In readable form. That would enable people who were either didn’t either, who didn’t have access to good newspapers, who were overwhelmed by newspapers to inform themselves quickly and intelligently. They talked about this at Yale. They talked about this when they were in the Army in Fort Jackson. They corresponded about this when they were apart after they graduated from Yale and.

Speaker In 1921, they reunited in Baltimore because they were offered jobs in the Baltimore newspaper together.

Speaker But what really drew them there and what really persuaded them to take the job was that they could be together to work on the paper. And so it’s been something that had been in their minds for a long time. And I don’t think that the basic concept of it ever really changed. I think they had a fundamental concept for this starting while they were undergraduates, a Yale.

Speaker Before we leave Yale.

Speaker Talk a little bit about, if you would, about the oration that Harry gave his senior oration, win a prize for it.

Speaker I think it’s the DeForest Prize and which was. It was a competition to give what was, in effect, a commencement speech by a student. And Harry gave this oration and the war was just over and the battle over the League of Nations, etc. was still very recent in people’s minds. It was a presidential election year. And the future of America’s role in the world was very much in part of the debate of this election year. And so Harry gave this lecture at Yale in 1920 in which he gave a kind of ringing endorsement, not so much of Wilson himself and the League of Nations, but of the idea of America as being an active and engaged power in the world of America, having a special obligation to the world in the aftermath of this terrible war. And you can read this speech, I think, and you can see in it the outlines of his much more famous declaration at the beginning of World War Two, which is article The American Century, which became so famous and controversial. Decades later, what do you think?

Speaker Sort of motivated that that kind of thinking.

Speaker I mean, granted, he was a senior in college and some seniors in college are more sophisticated in their thinking than others. But.

Speaker Where do you think this came from?

Speaker Well, I think this kind of vision of America as having a special obligation to play a role in the world came from, in Harris case, came in part from growing up in the missionary community where which really embodied this idea. Not the same kind of mission that Woodrow Wilson viewed, for example. But he grew up among people who saw themselves as undertaking a mission on behalf of not just of Christianity, but also of America in in China and elsewhere.

Speaker He also got it from the war. I mean, the American experience in World War One was one of the most superheated experiences in American history. And it was partly because there was so much dissent about the war that the defense of the war and the moral justification from the war for the war was. Publicized and and promoted with such energy by the government and by many other people. And there was a kind of artificially induced frenzy of commitment to the war effort, which was accompanied by, especially in Lucy’s case, a vision of what the world after the world would look like in the role that America would play in shaping that world. And so it fit very comfortably into his pre-existing worldview. And all of these things came together, I think, in the speech that he gave in 1920. The missionary background, the intensity of the war, the the shining idealism of Wilsonian internationalism. It was already beginning to fall apart. All of the things came together to shape that speech and to shape Luce’s view of the world after it.

Speaker How did America This is a broader sort of historical question. How did this country change after the war?

Speaker What was what was.

Speaker What is the character of the 20s that was different from what happened, what this nation was like before?

Speaker Well, America after World War One was a. In many ways, a very different place from what it had been before. There was a period of a year or two after the war of tremendous social turmoil, dislocation, the labor unrest, violence, anarchist bombings, the great red scare, race riots, inflation, recession. And the result of all that was to begin to create a much more conservative political climate than the United States had seen in the first 20 years of the 20th century. But the other thing that changed after the war was that after these first two or three difficult years, the American economy entered this long period of dramatic economic growth and buoyancy, and it created a feeling within at least middle class America of entering a new era. In fact, that was a phrase that people used to describe.

Speaker The 20s, the new era and loose very much bought into this idea that America had entered a new era and that Time magazine would be the clarion of the new era. This was a new modern age, and Luce was always attracted to what was new and what was modern. And this was a moment when the idea of the modern had a particular purchase on the imaginations of young people in America.

Speaker Well, how was it? I mean, how how was that a good thing? Specifically, what was what was going on in that?

Speaker Time magazine seemed to. Be right for it.

Speaker This is one of the things that that was happening in the 20s was a rejection of sort of old Victorian notions of decorum and propriety. And Luce was never a bohemian, certainly. I mean, he was a very. M. socially correct person. But he hadn’t absorbed at least a part of this new ethos, hadn’t in particular hadn’t was cynical. Like to H.L. Mencken, the sort of smart set view of the world. And he referred to people he thought were beneath him as Babbitts. He was a real intellectual snob in the way that a lot of young people were in these years. Luce was never quite that. But he he to sort of embrace this idea of there being a new kind of discourse in America and Time magazine, although its style has often been ridiculed and dismissed. It was part of this new age. I think it was smart. It was sassy. It was a little bit cynical. It was precocious and loose wasn’t all those things himself. But he was aware of that part of American culture. Brit ad was all those things loose wasn’t. But he he sort of admired them and liked seeing the magazine reflect them in a way.

Speaker What?

Speaker My Lockharts, when he meets love, meets her in Europe, opposites like his first serious romance.

Speaker As far as I can tell that. Meeting that he had with livelihoods at a New Year’s Eve party in Rome in 1921, 19, 20, 21. That was the beginning of the first serious romantic relationship of his life. I don’t know of any evidence that there was ever any serious. Romantic relationship in his life prior to that, and in fact, letters that Lewis would get from his friends at Hotchkiss and at Yale would refer to him as someone who was, you know.

Speaker Went to a great dance last night. But the course that wouldn’t interest you and you know, you’re on Nantucket, Ryan, spending the summer, the girls are just great. But that wouldn’t interest you. I think he was sort of social. I’m not misfit, but just someone who didn’t really join that kind of social life. He was saying, you know, through his last year at Yale that he didn’t really believe in marriage. No. Thought he’d have a more successful life if he was alone.

Speaker And then he met Layla, this beautiful, wealthy, socially prominent young woman who was spending a year in Europe as part of her education in Chicago. Lucent was very familiar with Chicago society because of his relationship with Eddie McCormack. So many things about her resonated with. Cricket where I was. What was I always just talking about, Lyla?

Speaker Yeah. What was the what was the when when he met her? What was the. What happened to him?

Speaker Well, the only evidence we have of what happened is, you know, what was in letters at around this time. But clearly he was smitten with her. And it was characteristic of him. It was. She became. Almost immediately, this completely idealized person. And he. Spent some time you saw at this New Year’s Eve party, spend a little time with her the next day, and then you see her for a long time, but he started to write to her. And then she came to visit him at Oxford for a couple of days. And then he met her once, I think, in Paris.

Speaker But in the whole almost first year of their relationship.

Speaker He was in her presence for less than a week. And yet by the time that year was over. At least in his mind, they were in love. And it was an entirely epistolary relationship. I mean, they started writing letters and he he had this vision of her as this perfect creature and as this beautiful, smart, rich, socially adroit person, all the things he wanted to be. And and so we fell in love with her. And there’s no question that he fell in love with her. I mean, he was desperately in love with her and, you know, waited for her letters and chided her. When did she when she didn’t write often enough. And I wrote anguished letters when he felt that she wasn’t committed enough and worried constantly that he wasn’t rich enough to for her family. But he was passionately in love with a woman he really didn’t know. And he came back from Oxford in 1921 and he went to Chicago and he took a job at the Chicago Daily News. And he was there for, I think, three months. And during that time, he saw a lot of her. That was really the first time he had ever spent very much time with her. And that just advanced his his infatuation with her. And I think it was the point at which she began to fall in love with him. But then he left and he moved to Baltimore and he moved to New York. And so, I mean, this this is getting us into 1922 and 1923. This is now three years after he’s met her. And except for those three months in Chicago, he still had hardly ever seen her. She would come through New York for a day or two now and then en route to Europe or on her way back to Europe with her mother from back from Europe with her mother, or is he. They’d go to Washington. He’d go down, see her for a day. Every now and then he’d go to Chicago. But, you know, it was every couple of months you’d see her for 24 hours. And that just made it worse, made it you know, the the love became more desperate. He was more worried about whether or not she’d write him more concerned that would she really love me? Will she will she really marry me? One of the things that made the early days of Time magazine so desperately anxious for him was that if it failed, he felt he’d lose her. And it had to succeed for him to get her. He had to have promise of being successful and wealthy. For him to be willing to marry her and for her family to be willing to allow her to marry her. And I think both things were true. It wasn’t just the family. It was her. She wasn’t going to marry. Some guy was going to make her live in an apartment. No. And. So it was a.

Speaker A passionate but very strange relationship among two people who were really much more different from one another than either of them realized. But it convinced themselves they were in love with one another. And there were certainly things about each of them that you can understand were attracted to the other. Harry was so smart and so. He was smart, he was energetic, he was serious. He was clearly someone who was talented and important and potentially important. She was beautiful. She was smart. She’d gone to the spent school in New York, which was the great finishing school for socially prominent women. But it was more than that. It was that one of the first girls schools, women’s schools in America, that tried to provide serious academic training to two young women. So I she you know, among the world of debutants, which is the world she inhabited, she was more intelligent than most of them, but she still was essentially a debutante. She lived a social life. And Harry loved that because it gave him access to a kind of society that he wouldn’t otherwise have access to. He was also troubled by it. He didn’t want her to be frivolous. He wanted both. He wanted an intellectual partner. He also wanted a. Socially adept partner and. She was certainly the latter. She was certainly a socially adept partner. She wasn’t really an intellectual partner to him.

Speaker And that’s, I think, part of what troubled their marriage later on, which is when he was when he was in Chicago, he worked for Ben Hecht. Yes, you know what? What what happened there?

Speaker Well, there are conflicting stories of what happened with in Lucy’s relationship with Ben Hecht. Ben Hecht wrote this ridiculous column for the Chicago Daily News in which he would find some event. This is not uncommon still. Jimmy Breslin and people like that still do this or done it for years. He would find some little event in Chicago and then he would embroider it to create some heartwarming or shocking or sensational story. And Luce was hired to be his leg man to go out and find the little nugget of truth out of which this fantastic story would be woven. Their relationship didn’t last very long. And Hecht years later, Hecht went on to become a famous radio personality and a playwright. And Lucy, of course, went on to become Henry Luce. And so years later, when both of them were famous. But Lucy was more famous or at least more successful. Hecht either wrote or said on the radio. I told a story about Loose working for him as a young man and said that he’d fire him for incompetence, that he just, you know, and it was meant to be a joke that, you know, here’s this fabulous, successful man who was an incompetent assistant to a young columnist. Luce remembered it differently and remembered him being promoted, respected, said he was too good to be just a leg man for a columnist. The truth lies probably somewhere in between. But it’s clear that Luce was not fired from newspaper. Lewis left working for Hecht and became a kind of cub reporter, which arguably was a promotion. So my guess is that Lucent heck didn’t get along all that well on that. Neither.

Speaker OK.

Speaker OK, moving on to talk, because we talk about Baltimore and how they connected. To talk about the magazine. What was their. Concept from the magazine.

Speaker And how do they see it as being different from what was already out there?

Speaker Well, Time magazine was envisioned as an alternative to, on the one hand, The New York Times, the preeminent paper of its time and ours. And on the other hand, the Literary Digest, the most successful magazine that attempted to present news to Americans. And both The New York Times, the Literary Digest seemed to them inadequate because they were ponderous in their view. The New York Times looked ponderous with eight narrow columns in the small headlines and limited illustrations and the long transcripts of speeches and, you know, sort of dutiful presentation of all the worthy news of the day. And Literary Digest was in May was the same way they would excerpt.

Speaker Other newspaper, other magazines and newspapers, they would long run long three and four page accounts of debates in Congress over intervention in Nicaragua or, you know, what the president had said about the tariff and so loose and hadn’t looked at these things and they thought, who? We’ll have the time or the interest to slog through this kind of news. I and we can do better. It’s unbelievably precocious to think that these two, when they started working on this, 22 year olds with between them. About five months of professional newspaper experience could create a national news magazine, but they believed it. I mean, this is a tribute, I think, to what and what it meant to be a Yale student in the early 20th century, what it meant to be a student at one of these Ivy League universities. You were ushered into the elite and you were trained to think of yourself as a leader. And they did. And they never you know, they had some doubts, but they they never lost faith in their ability to do this. Time was going to be three things. It was going to be brief. I was going to be comprehensive. It’s going to cover all the news, not just the city, not just the nation, the whole world.

Speaker And it’s going to be lively.

Speaker And that was basically the idea. It would be and would be organized. That was also extremely important. It would be a fixed method of organization. That was a phrase they used in their promotions in the early years. And it was very important then to think that readers could pick up the magazine. They know exactly where everything was every week. Everything would be in its own department and every week it would be the same in the same place. No story would be more than 200 words, although they did, in fact, stick to that for very long. And I mean, this was a very. Precise. Form of organization and conception of a magazine. And they started writing it when they were in Baltimore. They would, after work on work, worked for an afternoon papers that would get off early. And they go back to this sort of shabby mansion in which they had rented a room on the top floor. And the two of them and another friend of theirs, Tromeo, who was also working in Baltimore, would sit around late in the evening writing these stories and putting together and cutting them out and trying to figure out what they would look like in a magazine. And after a few months of this, they decided they were going to do it and they moved to New York and they set out to raise the money. And they and they began to recruit a staff and they rented an office. And they kept doing this. They kept sitting at the typewriters or at the desk and writing these stories and pasting them together and trying to figure out what worked and what didn’t. And they began subscribing to dozens and dozens of magazines and newspapers from around the world because they, of course, couldn’t hire a stable of reporters to cover the world. So they had to borrow from the publications that did. And they they clipped and they summarized and they rewrote. And eventually they got to the point where they thought they had something. And the first magazine came out in early 1923, wasn’t really very good, but it was certainly different from anything else that had happened in journalism a long time. And. You can see in it, I think, the the origins of what Time magazine later became in its really successful phases.

Speaker Well, what was when you say was something different, what was new and different about?

Speaker Well, I think what was new and different about time is that it was written self consciously. For what Lucent hadn’t believed was a new era in which people were busy. People have complicated lives. People didn’t have time to sit down and read. Forty five densely printed pages of The New York Times every day to learn about the world. It was part of the same impulse that produced the Reader’s Digest and other kinds of condensation of knowledge that were becoming more and more popular in the 1920s. And so what made it different was that this was a magazine. They believed that you could sit down and read from cover to cover it in our. And they really believed that people would read it cover to cover, they used to talk about their cover to cover readers and they knew some people didn’t do that. But that was the image they had of a reader, someone who would sit down one afternoon, pick up TIME magazine and read the whole thing and feel that they learned about what had happened in the world that week. And there was nothing like that. And the other thing that made time so. Innovative and important is that it wasn’t designed for any particular city or region or part of the country. It’s designed for everybody. And there was no news organ anywhere in the United States of any consequence. In the early 20s that reached everybody in the country. Radio didn’t do news seriously at this point. Movie newsreels weren’t really established at this point. No newspapers had national circulation. The magazines that purported to present the news like full every digest, really had very little news on them in the end. This was the first truly national news vehicle. And of course, it didn’t reach everybody. And in fact, it had a tiny circulation in its first couple of years, but it aspired to reach everybody and it had readers all over the country. Even at the beginning.

Speaker Just curious, and this is actually not part of. The film itself was created into part of the work must have therefore been with. How do we distribute something?

Speaker Oh, absolutely. Well, I mean, starting a magazine, which is still extremely difficult and maybe more difficult, was a very challenging thing for two kids with no money to do. And so they had first to raise the money, which for the rest of his life, Luce remembered as the most difficult experience of his life, raising that hundred thousand dollars that they thought they needed. They never raised it, actually. They only got up to eighty seven thousand dollars. And they decide to go ahead with that. And they thought this would take a few weeks and it took almost a year. Then they had to hire staff, and that proved very difficult and they made all sorts of mistakes and people came and went in the first few years. And then they had to figure out how to distribute the magazine, how to get people to buy it. And they hired this man, Roy Larson, a kid who just graduated from Harvard, who had been the business manager of the advocate at Harvard, which is the literary magazine at Harvard. I mean, hardly the kind of experience you would imagine would make somebody the circulation manager of a major publication. But, of course, they couldn’t have recruited anybody who had real experience. And so they recruited Roy Larson to be their circulation manager. And he was making it up as he went along, too. But they tried everything and they sent out circulars. They figured, you know what what mailing lists should we mail to? When they got the subscription lists of some other magazines, they got people who, you know, they used the social register. They they used anything they could think of to. Find lists of people who they thought might be attracted to time. They spent a lot of money sending out circulars. They spent a lot of time attracting famous people to endorse the magazine whose names they would love them to use their names and publicizing it. This is one of the things that’s all. I’ve always found most striking about this story is that everybody in this organization was 22, 23, 24, Brit and Harry Reid, the oldest people on Time magazine. In its first few years, save maybe one person who was a couple of years older than them. Everybody who worked in this magazine was in his and in one case her early 20s. None of them had any experience. And yet they set out to do this extraordinary thing. And there were lots of fits and starts and there were lots of ways in which their inexperience showed.

Speaker But they did it. And. They were 24 when it came out.

Speaker Do you think that when they start to Lewis envisioned that this was going to be a way that he might access power? I think he’d look that far ahead and saw that this could be his way to become a. This is an.

Speaker I don’t think in the beginning Luce had a vision of itself as having. I’m sorry. I don’t think it’s the beginning Luce thought of himself as someone who is going to have broad political influence. And in fact, he never really did have broad political influence, nor do I think he originally thought of himself as someone who is going to be one of the great movers and shakers of American life and move in the high social and intellectual political circles in which he eventually moved. I think he wanted.

Speaker To be wealthy and.

Speaker He hoped that this magazine, if it worked, would make him wealthy. I felt I think he wanted to be a success, wanted people to see him as a brilliant success because he had been a brilliant success at Yale and at Hotchkiss. And that was his image of what he was supposed to be, was also his parents image of what he was supposed to be. And I think he expected to have influence through the magazines. I don’t think he realized for quite a while, actually, how the magazines could become a platform for him to have influence in other ways.

Speaker What about this idea of using people in terms of its innovations?

Speaker This idea of telling the news to people, was that something that was new and different? Was that conscious, a conscious choice?

Speaker Lucent hadn’t did feel that much of what was presented as news was too dry and formulaic and institutional. And so one of the things that they thought would make the presentation of the news more lively and accessible was to build it around people. And so from the first issue of TIME magazine, there was a portrait of somebody on the cover and then the story inside about that person. And a lot of the news and time, not all of it, but a lot of the news and time was told through the activities or the statements of an individual. One of the things that made this attractive them is that it was a lot easy to write colorfully about a person than it was to write colorfully about an issue or an event. And much of the famous language that time invented for itself was created to allow them to describe people. And you know, the way they would use titles, you know.

Speaker I’m blanking here, but the way they would, you know, financier Baruch or. Actor Pickford or actress Pickford? I mean, the language of time was a language about people meant to make people seem more vivid. The. The profile, the you know, the cover story profile actually came much later. Originally, there would be picture on the cover and the person in the picture would be mentioned briefly in one of the 200 word articles. But over time, the cover story was always a profile of a person. And so from the very beginning, people became the vehicle through which time would make itself different from other news sources.

Speaker We got. A story, and I don’t know if it’s apocryphal. And I wonder if you have any insight into it about how they arrived at the Man of the Year.

Speaker That Linberg, they kind of.

Speaker Put the Lindbergh story in the back pages and they realize they’ve kind of blown putting on the cover and therefore they established the man of the years. Have you heard that?

Speaker I don’t know if that’s true. I do know that with Lindbergh. No, they had they had an aviation section in the magazine and in their commitment to having everything in its appropriate place and everything rigidly organized meant that when Lindbergh prudent flew to Paris, that would go in the aviation section, the back of the magazine, because, of course, it was an aviation story and there was no way, given this rigid organization, to figure out what the most important story was and put it at the front. And that’s what the cover story began to. I don’t think I’ve ever heard flowing in here before.

Speaker OK, so we can pick it up from.

Speaker Everything was in its place, they put everything in it, put everything in its place, and aviation had its place in the back of the magazine, and that’s where the Lindbergh story went. And so they realized that they’d blown it. You know, that everybody wanted to pick up the magazine to read about Lindbergh. And there he was on page 22. So that was one of a number of things that made them feel they had to have more flexibility and that helped create the cover story and probably contributed to the idea of the Man of the Year, which allowed them to exploit Lindbergh’s popularity once again.

Speaker But I. I have to say, I don’t I don’t know that the details of how they came to this decision.

Speaker What was the response in the 20s, and I don’t mean just this is sort of the first year.

Speaker But as it grew and became a real phenomenon.

Speaker TIME magazine still talking about it in the 20s, early 30s. What was the response of. Journalists are intellectuals, serious thinkers to time.

Speaker Well, I think it was a wide range of responses by journalists to time in its first year. In the beginning, nobody really noticed it very much.

Speaker It was a little sorry stretch.

Speaker We’re where we.

Speaker Well, we were actually. This is what I want to get the response of of people, journalists, really, journalists and intellectuals to my massive group.

Speaker Oh, right, okay. I think in the beginning, very few journalists paid any attention to time, it was this little magazine, that small circulation run by kids. But as it began to grow and as it began to make a real presence for itself in the journalism world, there were there was a wide range of responses to it. Old conservative newspaper people looked at it with a mixture of bemusement and I think condescension and. Aside as frivolous and not serious, other people saw it as and saw and particularly saw its success. As a sign of a different way of presenting news as a way of crossing that border from serious, sober presentation of what’s important to making the news entertaining and making it commercially appealing. And so you see the formation of Newsweek at the end of the 20s as a kind of copycat magazine. And you see changes in some newspapers that I think you could well imagine were inspired by TIME magazine and the writing of newspaper stories.

Speaker So it it began slowly to have an influence on the way news was written, the way other magazines and even some newspapers behaved. But it was also a challenge to the traditional newspaper.

Speaker And they looked on it much more skeptically and it was more concerned. There was another way in which time had an impact on journalism in these years. Everybody at Time magazine missed everybody in an editorial position at Time magazine was a graduate of an elite university. Every single person. Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Oxford, Columbia. That’s where they all came from.

Speaker And in the newspaper world, college graduates were actually pretty rare. That wasn’t the kind of career that a graduate of elite university would choose. The world of journalism in those years was a sort of raffish sawdust on the floor kind of world with, you know, gruff, crusty people who were anti elitist, smart, anti elitist people. And here was this, you know, Ivy League social register crowd running a magazine. Luce always said through his whole life that one of the things he had wanted to do was to make journalism a respectable profession. And in his view, making it a spectacle, a respectable profession, meant attracting to it socially respectable people like himself, people who’ve gone to Yale, gone to Princeton, gone to Harvard. And time was very successful doing that. And throughout its history, at least, its history in Luce’s life. Those were the kind of people who always came to Time magazine.

Speaker That brings me to another question that you and I were just talking about. Why did I lose?

Speaker You know, going back a little, you know, a few years. What what motivated lose to do this as opposed to go into business or something else? Given that it wasn’t at that time considered a respectable. This is what what was going on in here that made him decide that he was going to pursue this kind of career.

Speaker I understand why Lewis chose journalism. You have to understand the things that made him the person that he was. I mean, he was ambitious. He was achievement oriented. He had this sense of mission. He had this drive for success. But he also had and this was visible very early in his life, even as a child. And China had this incredible curiosity. And maybe it was growing up in this to him isolated place and trying to figure out what the world was like from such a great distance, the world that he considered important. But for some reason, he had an insatiable curiosity about the world from a very early age. And when he got to Hotchkiss and began to work on the newspaper and the magazine and again at Yale and the Yale Daily News, he loved doing this because it was a vehicle through which he could learn about all sorts of different things. You know, it was how he learned about Yale when he was at Yale. Healing for the Daily News and covering all these different things that were going on at the University of. And you can see in his letters home. As early as his graduation from Hotchkiss. And what did you do when he graduated from Hotchkiss? He spent the summer working on a newspaper in Springfield, Massachusetts, all by himself living in the YMCA. Not knowing a soul. But he was working on a newspaper.

Speaker He was there was a kind of romance. Not so much of the world of the newspaper. Because he really didn’t like that world very much. He didn’t really enjoy being in a newspaper room, you know, and didn’t didn’t really respect the people that he met there particularly. But. Doing something has allowed him to learn something new all the time. And I think that’s what drew him to journalism. His social ambitions, you would think, would have led him to Wall Street or to the business world because he’d be rich and to be socially connected. I think, you know, in his heart of hearts, he knew he’d be bored. You knew that wouldn’t satisfy him. And so this was a way both of plunging into journalism, which provided the window onto the world that he was so desperate to have. And also doing it in a socially respectable way, doing it in the company of fellow Ivy League graduates.

Speaker And I think that really that really.

Speaker Now, what was having an abusive relationship as well, or co bosses or the founders of this company? What was their working relationship? Once they had founded the magazine?

Speaker Well, Hayden in loose in those early years a time. Were both inseparable partners. And intense rivals. And the partnership and the rivalry sort of.

Speaker Jousted with one another throughout their relationship on the magazine. They both realized that they needed the other. The idea was that. They would alternate roles at the magazine that. Hadden would edit the magazine for a month and Luce would do the business stuff and then Luce would do the editing and hadn’t do the business stuff, but Hadon couldn’t do the business stuff, or at least wouldn’t. And so there was a kind of de facto decision that Hayden would be the editor of TIME, even though on paper they were both editors and Luce would be the business side. He wasn’t particularly happy about that, but he understood that if he didn’t do it, it wasn’t gonna get done. And he admitted in a letter to Lyla at one point that Hayden was the real editor of Time magazine, but he told her not to tell anyone. He would when he could plunge into the editing and he did play a role in the editing the magazine, but Haddon was clearly the dominant figure in the editing and he was, you know, out, you know, making deals with paper suppliers and finding printers and prodding the advertising company to get the more advertising and buying desks for the office and all the stuff that you need to start a business. And Hadon was sitting at the desk smoking cigarettes and barking orders to people and taking his blue pencil and marking up stories. And I think it must have been painful. For harrying to watch Brit do all the stuff that had really interested him with that was really why he went into this, too. That’s what he wanted to be doing, on the other hand. I think he. Was pleased with his talents as a businessman, pleased to discover that he was as good as he was, pleased to discover that he could do as many different things in a day as he did. I think he and Brit were true friends, but not in a conventional way. I don’t think there was.

Speaker Intimacy, personal intimacy between them to be shared, their innermost secrets with one another. But they were bonded in a way that few people are really. And and I know.

Speaker That some people are quite cynical about their relationship, W Swanberg, who wrote the first major biography of Lewis, thinks that Lewis was actually rather pleased when hadn’t died. And I just don’t think that’s true. I mean, I think obviously Haddon’s death opened up possibilities for him that hadn’t been there. But I I think he was devastated by Haddon’s death and confused by it. It was all the more shattering because in some ways he benefited from it and he didn’t want to think that that was the case. And I think he felt desperately alone and abandoned. Well, haven’t died. I think he really didn’t know how to go on without him, although he figured it out pretty quickly. It was an extraordinary relationship and there are not many relationships I can think of when prominent people that are so, so intense and so conflicted as this one was you mentioned.

Speaker I never heard this before. They called him, so I called him the Brach.

Speaker He wasn’t alone in doing that. That was his nickname. Time was the brach. And it was and for a long time, I didn’t know what that meant. The brach was a Dehra was derived from Caliban, the figure in in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. And somehow it got transmogrified into the brach. And it was a comment on Haddon’s sort of elemental personality. You know, Caliban was this creature who was all instinct and all earthy and not not cerebral. And that was the you know, at least within the world of this little world of Time magazine. That’s what Caliban was. That’s what Britain hadn’t. Was this Caliban like figure to them all emotion, all instinct, all energy. Course, he was smart and he was he wasn’t an intellectual, but he was very smart. And he did think he was he wasn’t really like Caliban. But that’s where the name came from.

Speaker Brent.

Speaker What? What about Harry?

Speaker I guess this sort of squeeze into Harry and Teddy in their relations?

Speaker Well, Teddy White was one of these, you know, extraordinarily bright young man whom Luce liked. And I think probably reminded him of himself and, you know, went to Harvard. I had been China scholar. And so he had all sorts of things that loose really admired. And Teddy White, for his part, although he’d gone to Harvard, he’d been a scholarship student. He was a Jew, which was unusual at Harvard in those years, was kind of marginalized and. The fact that he was liked and admired and sort of embraced by someone like Henry Luce made a huge amount to him and so was a really quite close and intense relationship that they had. And Lou sent to China to be their China correspondent, which was a tremendous statement of confidence and an extremely exciting to Teddy White because he was a China scholar himself. So he thought of himself. And also because China was so important to loosen to the magazine. And he got there and he began reporting on what was happening in the government and what Chiang Kai-Shek was doing and how things were going in Chongqing. And he just saw, as everyone there saw, that this government just was pathetic, that it was incapable of meeting the challenges that it faced and that things were looking increasingly hopeless. And the Chiang Kai-Shek really was not someone who could reliably support American interests if there were if there were a Pacific war in which the America would in which America was engaged. And he said, you know, this this is the you know, the way time worked and still works is that the reporters send memos back to New York. And out of these memos, the writers produce the story that goes in the magazine. So White was sending these long memos back about Chiang Kai-Shek and about the government, and they were getting increasingly critical. And, of course, he was there in a war. And the war was, you know, making its way into Chongqing. And it was a very stressful experience. He was getting more and more emotional and impassioned in his writing. And these memos would come back and Bruce would see them and just. Just lose his temper and he infuriated him and he made sure that the stories that actually appeared in the magazine were completely sanitized and that all of the criticism Machain was gone. And the stories became unrecognizable as products of the memos that the White had written. And, of course, the magazines eventually found their way to China. Teddy White would see them and he would write these embittered letters to Luce complaining about the distortion of his work and so forth. Luce would write these letters back. Explaining that this is my magazine. And just because you think you know what’s going on in China, there, you know, there are ways that other people know things about trying to. You don’t. So the relationship really fell apart over this. And finally, at one point, Luce called him back. And made it clear he wasn’t going back to China. And it’s never been quite clear whether Teddy White was fired or whether he just left. But it was like the breakup of a marriage in a way. I mean, at least from Teddy White’s point of view, I don’t think White was ever as important to loose as loose was to white. But for white, being at Time magazine had been. You know, like being a part of a family, you know, it was his entree into the wider world. Even though he’d been to Harvard, this was it. And and Luce was almost a father figure to him. And to be expelled from this paradise, as he had once seen it was a tremendous blow. And their relationship recovered to some degree in later years, but never became what it had been.

Speaker At what point did Harry begin to. Well, let me ask you this. Why were his magazines perceived as anti-Semitic?

Speaker Well, I don’t believe that the magazines were actually anti-Semitic. But it doesn’t surprise me that people sometimes thought they were. I think there were people on the magazines who were anti-Semitic. And we have to recall, unfortunately, that many educated and otherwise respectable people in the 1930s were anti Semitic. I mean, it was often called genteel anti-Semitism, which didn’t take the form of overt bigotry and treating people badly personally. But just to kind of condescension. I think what the magazines did that most often seems anti-Semitic and probably is, is gratuitously identify people as Jews in a way they wouldn’t identify people who were Catholics or Protestants or anything else. And, you know, even at times using Jew as a title in the way they talk about, you know, politician doors or Finistere Baruch, you know, there would be Jew so-and-so. So you can see where the sense of this is now somebody’s back anti Semitic magazine came in. There was also the foreign news section of the magazine in the mid to late 30s, edited by their Goldsborough, who I think probably wasn’t anti satellite and who in reporting on Nazi Germany.

Speaker In some ways, whitewashed, what what Hitler was doing to the Jews wasn’t nearly as critical of Hitler, in fact, sometimes not critical at all. And so that helped fuel these complaints. Luce himself. I don’t think was anti-Semitic. I hadn’t I think was and Hayden wrote often about Jews not. Ugly, ugly ways. But just about Jews, as if they were a separate species and needed to be identified as such, and Harry picked up on this a little bit, especially when Hatton was alive. And you could find occasionally pieces of this language in here, his own writing. But through most of his life, you never see this. So I don’t think anti-Semitism was much of a factor in Harry’s own thinking, but it certainly did make its way into the magazines in subtle ways. I mean, not not in ways that were particularly overt, but in ways that people who were sensitive to this issue, as many people understandably were, would rightly consider to be offensive.

Speaker When at what point did Harrison with getting on the bandwagon in terms of that? Germany was a dangerous regime. We have to do something, we have to be. We have to we have to be more aggressive.

Speaker I don’t know what the exact moment was in which he decided that Germany really was a mortal threat to democracy and that fascism was something that had to be opposed. I think it was 1937, 1938, probably Kristallnacht had something to do with it. It was around that point when he that he fired Leered Goldsborough, the magazine started treating.

Speaker The magazine started treating Germany in a much more hostile way. So certainly before war was declared. He had come to believe in you before 1939 when the war began in Europe. He had come to believe that Hitler was a real threat to freedom and that fascism was a real danger to democracy. And the magazines did a kind of about face at that point.

Speaker Before I started, well, I’m wondering if I want to remember to get back to Wendell Willkie on this this line, what what do you think led to him writing this, The American Century? What was its significance?