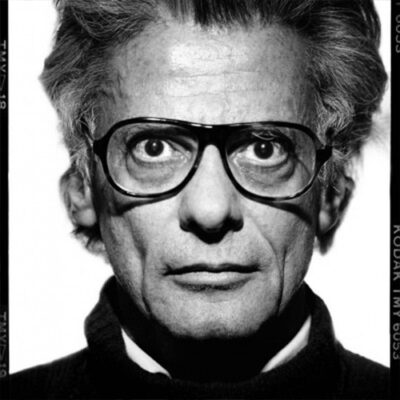

Speaker Well, first of all, I was shocked to get a phone call that from The New Yorker that Avidan was going to take my picture and it was in the middle of that huge snowstorm two years ago in New York, who was a late snowstorm in February or March or something like that. And I was here on my way to England and doing three performances at Bam! And Avidan had been a important part of my own development and may in some ways have led to the work that I do, because the year that I developed it, I come into New York from Pittsburgh, whereas teaching at Carnegie Mellon to see his exhibit, the exhibit of his fashion photography at the Met.

Speaker And it was just it really had a big, big, big effect on me. I felt like it chiseled away some layers and got to another sort of part of me. So I was really shocked that would ever hear from Richard Avina.

Speaker And he called me himself in New York. This is Dick Avidan or something like that. And he had just seen the show. He’d gone to see the show in Brooklyn. He said, I went to a dinner party and I walked in and I said, everybody stop everything.

Speaker I had just seen. So, you know, that that was very flattering.

Speaker And then I was to call him the next day and I called him the next day. And he was very frazzled, very harried. He had gone all the way to Washington to shoot gays in the military. And because of the snow storms, I don’t think they ever even got to do the shooting. So I saw like a whole different Abbadon in that phone call, very annoyed and harried and stuff. But at any rate, I went the next day across the park still and in all the snow to the shooting. And the first thing that was different about any other photograph I’d had taken by a major photographer was that there was no makeup artist.

Speaker All right, so I’m not probably as vain as I maybe should be.

Speaker And it sort of I just meant had a mental note rather than going, you know, just over here, you know, when Albert watching it on my photograph.

Speaker They did. My hair was like a whole, you know, two hour kind of thing. And the same thing with Mario and Mark was like a big deal. Right. So I kind of went, oh. And he just said to me, you have a lot of makeup on and it makes you look older. Wait, wait. Wipe it off. Right.

Speaker And then he gave me a shirt of his a black shirt of his to wear. And I went into a small room. There were two young people there who were his assistants. And we did it in maybe less than fifteen minutes. I’d say maybe five minutes. Maybe 10 minutes. And then the rest of the afternoon. Or it felt like an afternoon was probably no more than 45 minutes. We looked at a book of photographs that he did with James Baldwin, a book he did on the 60s, which is very interesting and particularly interesting to me since I was going to be continuing my work in L.A. and he showed me this book in the context of a book he was going to be working on with Mike Davis, who’s a big, you know, socio historian of Los Angeles. And then we went upstairs and looked at the looked at his new book in galleys. And it was an incredible afternoon, really. And I would say that I am more remarkable in a way than my sitting was going through his work with him.

Speaker Don’t know how he directed you. And he got into a particular.

Speaker He just asked me to do two of the characters. I think he knew which ones he wanted me to do. As I recall. And we just did him. And he just was like, one, two, three, four. And he course, he flattered me, you know, he said, oh, it’s so great to work with a talented person.

Speaker And that was it. Right.

Speaker And he showed me where Burt LA, you know, had the headset for the very famous photograph of him.

Speaker We’ll see as one of the pictures comes directly out of character that you created for your show, that too.

Speaker Sure. I think this is one of them. You know, I think the larger photograph comes from this character, but I couldn’t swear. But I think it is. And this is the father of Gavin Cato, who is a little boy who was killed at the beginning of what became the Crown Heights riots when a member of a motorcade with the Lubavitcher Rabbi Schneerson ran a red light on the sidewalk and killed Gavin Cato, seven year old boy and injured his cousin.

Speaker And the father of the boy then gives me account of this.

Speaker And meanwhile.

Speaker It was to. Angela was underground. She was trying to. And gardening was still. And there was trying to pound him. And I was the father and I was it choked and pushed a minute, sarcastic were to pass towards me front, please. As I was trying to explain is why can’t. These are my children.

Speaker The child was hit. You know.

Speaker Do you see that character, would you describe the pictures that emerged in response?

Speaker Well, I. I was very surprised when I saw the picture. I might have mentioned to you that I was invited in in Los Angeles. It was summertime after that shooting to a party for four Los Angeles artists that The New Yorker gave. And it just happened that that was the same issue. That was the issue that came out that week, was the issue that my photograph was in. And Rhonda Sherman from The New Yorker said to me.

Speaker Very seriously, she said. And very cautiously, she said. Your photograph is in this.

Speaker And she said. It’s very strong.

Speaker I like that. I thought a net oh, what does that mean? It’s very strong. And so I opened it up and I was shocked.

Speaker Because the large photograph in particular, I would say, looked so angry.

Speaker And I disassociated it from the fact that I was performing. And I thought. I can’t believe that I project that much rage. I know I have rage, but I couldn’t believe it.

Speaker And then I was surprised at the volume that my hair had. And then in contrast, because I think what he was working with was something dark and something white. In contrast, the other in the one I saw, the other picture, I thought. I can’t believe that I’m that light. And then the other thing I thought that particularly the lighter picture of me captured was how tired I was at that particular time of my life. I was really, really, in reality, exhausted. And I wondered if the normal person viewing that picture would see how tired I was.

Speaker What else? The picture was revealed.

Speaker Well, I think the picture I would say the thing that captured it, captured that was me, was that I was very tired at that time in my life. I don’t know, you know, I guess I’m still even though I’m quite a mature adult at this point. I don’t know how good I am at seeing myself in relationship to what others see in me. And I think that I probably fell into the trap that I imagine a lot of people get photographed by Avidan fall into. Which is that we are flattered that this very famous fashion photographer is going to take our picture and we forget that the fashion photography is a there is only a part of his work and that he actually, you know, he photographs much more than that. So in some ways, his fame as a fashion photographer caters to our own narcissism. So I certainly did it to some extent, think that Avidan could make me a glamour. So I was surprised about that.

Speaker But the more I looked at the bigger picture, the enraged photograph or who I think is was my performance of Gavin Kato’s father.

Speaker The more I liked it, the more I was drawn to it, because it wasn’t just rage. It captured as well the persistence of Mr. Kato. The direct gaze. I don’t know if that direct gaze is like a part of my everyday personality, but I know that it is a part of my basic personality, which is a persistent gaze.

Speaker My mother used to tell me I was a little girl. Don’t stare and close your mouth. So it’s something that has been deconstructed about me that I’ve had to recompose, which is my nature to want to stare straight at it. And certainly when you deal with race in this country, you’re not really rewarded for staring straight at race. But in the case of fires in the mirror, I was rewarded for doing that.

Speaker So I would say that the photograph. Capture that thing, which is both acceptable and not acceptable. My mother saw the photograph. She went to buy it at a newsstand.

Speaker And at the time that The New Yorker came out, something else came out that I was in. And she said with great pride, you know, to which I imagine she does all the time. It’s embarrassing that she said that the person to stand up. I need that magazine. My daughter is in that magazine.

Speaker She opened it up and she showed it to the lady and she shut it. She doesn’t look like that. Show me one. You know, and the other one, I’m sure, was more, you know, pretty.

Speaker So as a director, you didn’t really experience I mean, watching Abbadon Direct was a very brief and compressed experience, very compressed.

Speaker You won while you get they certainly get the feeling from meeting him in the first place. I mean, I think his intelligence is really, really, really a parent. At least in my case, I could feel it. You know, his intelligence and. I respected that. And I got the feeling that he knew what he wanted and that might have had something to do, too, with why, for example, when I first came in and I thought, you know, oh, there’s no makeup person here. You know, I felt I was willing to go along with the fact of this is business. Let’s get right to business. And the the the session felt like that, too. You know, he was very gracious. But I certainly felt like I wanted to do what he asked me to do, which I would say is a big part of what directing is. I mean, if you can bring into directing that, you can make the person that you’re asking to do something feel as though they’re going to do it. That’s that’s half the battle.

Speaker Why do you think he chose that role?

Speaker I wish I could remember. He had just seen the performance two nights ago or three nights ago. And so it was very fresh in his mind.

Speaker And. And.

Speaker I don’t know, it’s a very, very, very powerful monologue. You know, it’s very unusual language and, you know, it’s a man.

Speaker On the edge, you know, really full of emotion. I mean, I kind of wish she photographed Mr. Kato at that time in in his life. It’s very raw person.

Speaker Talk a little bit about that and how you created that role and what it tapped into in yourself in that picture. Well.

Speaker I was attracted to Mr. Cater largely because. Well, when I started this work that I do, which is interviewing people and performing them 12 years ago, what I was trying to do was find a way to get people to talk to me through.

Speaker And in spite of language, that is to say that, you know, language is a mask. I don’t mean that we lie. But it’s this thing that’s in front of us. It is not us, you know. And victory is when you can speak your mind or speak your truth in spite of limitations of language. So that’s what I’m looking for, my interviews as this kind of nakedness. Harold Pinter said that speech is a strategy to cover nakedness.

Speaker What I’m looking for my work is the moments when nakedness comes through that strategy. In a language you’ve given me three questions to ask people, which would most likely have that happen. One was, have you ever come close to death? The other was, have you ever been accused of something that you did not do? And the other one is, do you remember the circumstances of your birth? So when I went to interview Mr. Kato, we did this on a street at night in Crown Heights. He stood really close to me like as though almost as though I could save his life very, very close. We start talking. And yes, he came close to death. He came close to the death of his son. That was clear.

Speaker Yes, he was accused of suddenly that I didn’t ask him those questions. By the way, I haven’t asked those questions in 12 years. Those questions just ask. You know, taught me how to listen. I never, ever ask him any more. We were just talking about this event. So in the course of talking about it, his tells. He starts talking about the death of his son. And he starts talking about being the police, beating mother back when he’s going, you know, it’s my kid.

Speaker These are my children.

Speaker You know, they’re beating him on the back when he’s trying to lift the car off his son. And we talk on and on and on.

Speaker And then he gets this point in talking where he says to me, sometimes I think there’s no justice.

Speaker He’s had been weeping right before this. The Jewish people, they are very high up. They are running the whole show from the judge right on. There’s something I don’t understand. The Jewish people, they told me, is certain people I cannot do and certain things I can see, certain people I cannot be seen with. And they told me they made it very clear that they could try the case out unless I come them with pity. I don’t know what you’re talking about. I don’t know what kind of crap is that. I’m not going to do anything I don’t want to do. I’m not going to say anything I don’t want to see. I’m not afraid of them.

Speaker I am one of the special. I am a special person. I am a man born by my foot. I born by a foot. They say when a baby come in by a foot. It had a cut. The mother ordered baby die.

Speaker I born my foot. Yeah. We’re not special. Right. So.

Speaker Here is this man talking about the circumstances of his birth. I asked that, so when I finished the interview, I went back to Manhattan on the subway and I was just like, oh, my God, you know, it’s like my all my work coming to a certain point. And in many ways, I committed to the Crown Heights story because of that. I just thought that was like, you know, magical.

Speaker And.

Speaker So he, for me, spoke in a very unique way, a relatively uneducated man speaking in a way that I would not have been able to mimic had not I had training in Shakespeare, for example. He crossed great spences of consciousness as he spoke to me.

Speaker And that is what attracted me to him. And what I think makes having the opportunity to perform his material always very, very exciting. I don’t know. And maybe there are some things there that were attractive to Mr. Abbadon as well.

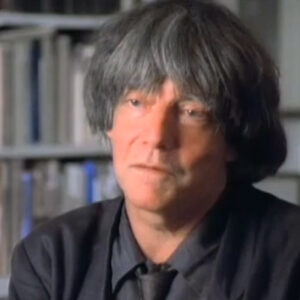

Speaker How about talking just a little bit more about you are in Pittsburgh. What was it about Dick’s work that had such a profound effect on your life? Van.

Speaker Well, you know, it’s hard, isn’t it, for me always to.

Speaker Nessus to give words to why.

Speaker Certain artists. Are able to speak.

Speaker Maybe at that naked point the painter is talking about, you know, in my case, being interested in language, the neck, the clothing, what clothes, the nakedness is is one, which is words. And I think that even though these were photographs of of beautiful women and beautiful and exotic clothes, there was something else that was coming through to me about Avidan.

Speaker And I think it was his intelligence.

Speaker I think it was the vigor of his intelligence, the intensity of his intelligence. And I felt that similar vigor with people in other fields. You know, I’m thinking of a surgeon that I interviewed, the head of pediatric surgery at Sloan Kettering.

Speaker A man named Axelrod.

Speaker Thinking of him, I think we may have mentioned before, Bernstein, Aaron Bernstein, a physicist I talked to at M.I.T. and a person’s job doesn’t necessarily mean that they that I’m able to tap into this feeling. And I would say it’s something about that feeling came across me at the Met. And it liberated me at a time. And it was good that it liberated me at that time. I mean, my job at Carnegie Mellon was my first academic position. It was a tenure track position. And I came to see the show, as I recall, in the fall.

Speaker And that quick I knew I’m going to leave Carnegie. And it was a part of my, you know, decision. And, you know, and by the end of the year, in fact, I said, look, I’ll go to New York and walk dogs rather than get caught at that.

Speaker I was in my 20s then get caught in academia because I was just scared that it was just going to kill me. You know what I mean? And I think that life that I felt at that museum in his exhibit, just like sort of reminded me that what I was looking for, I had to find elsewhere, you know? And I even became very interested in fashion at that time as an outsider. I started subscribing to WW d, just almost like an anthropological kind of way. And I was working on a play at the time about a a killer in California, believe it or not, who a man who had called the zebra killings a man who is black man who who had shot randomly shot white people. And I started working on trying to juxtapose those killings with, you know, with a designer. And so I was really interested in learning more about that world, too.

Speaker And then I attempted to do that. Do you think this is the very basis of what I intended to disintegrate the boundaries of race?

Speaker Well, I think I’m looking at Zazie. What strikes me is that Avidan was understand something. About the basis of theater and the basis of performance, which I think many of us would like to get to, you know, again, in spite of the lines that were given, in spite of the roles that were given, in spite of the limits of the types we’re given to play. Right. You know that let’s say if I were to do a sitcom, you know, I’d be given a a specific type or let’s say if I had to play a a somebody who the bottom line is, is is is an updated mammy. Right. I mean, if we were to look at most writing now, we would. For me, we’d be going back to types that were actually. Types based on race and maybe negative stereotypes based on race, and then my job would be to try to make that better, right, to look at a role, even if it it’s like a secretary and the look at that and go. It’s really a mammy in a secretary’s clothes. Now, how could I stretch it? It’s too bad that we had that we had that interruption, that roadblock, because really, you know. The history of theater and acting is much, much greater than that, it’s much deeper than that. Want to get that out of the way and go to the root of it, which is something more like what Zazie was doing in those streets, which is that it’s about. A tragic figure. And it’s about a clown. It’s about a smile and it’s about a cry, right? It’s about a jump for joy. And it’s about a scream. And it’s almost as though it is something that is beyond language. And in spite of language, it’s a spirit. You know, acting comes from a spirit, which is the ability to. Encompass in the human body, in human form. These bigger feelings. But to give face to them, to give a mask to them and to give more than that, to give a body gesture to them. And what excited me about the photographs of Zazie was that he captured at once the freedom in her body and the ability that she had to go almost to those archetypal recognizable forms. The delighted clown and a tragic figure to both of those. And, you know, it’s really a collaboration in some way between the two of them, right? Is that she does it and he has been able to see what she’s doing. She might not even know what she’s doing. She she might. Not at all. We don’t know her. We don’t have her here. We only have his. His, her. So as an actress and director, it’s useful to you, right, because it’s a reminder to me, it’s a reminder to me of of. Where I can go, it’s a reminder to me.

Speaker That.

Speaker That energy exists in the overall general huger historical imagination. And that huger historical imagination has something called acting, right? Which is bigger than me and bigger than the circumstances of my time in this particular street performer got a hold of that. And it gives me some place to go if I were working on a role. I might go back and look at that photograph and steal that pose. To have it teach me something about the role I wanted, I might go back to Bert La crouched in the corner.

Speaker Of Abbadon studio, because I never saw Laura’s performance in Goodell, never saw it right? I think I heard it on a recording. I never, never saw it. I might steal that and take it and wear the pose. You know, my grandfather told me when I was a kid. If you say a word often enough, it becomes you. That’s also the basis of my own work. I might take that photograph of evidence to see what it teaches me and use it in a role.

Speaker Right.

Speaker I need a Kleenex. I’m sorry. It’s a pop.

Speaker So bear with me on this. Yeah, I’ve actually thought about this, you know, since we talked about it. And recently there’s a scholar who’s getting more and more more well-known than Patricia Williams.

Speaker She wrote a book called The Alchemy of Race and Rights, which was Harvard Press, which was very popular. And I was recently reading a new manuscript of hers. And she actually talks about Marian Anderson in relationship to Lani Guinier, that, you know, how Lani Guinier was called a quota queen. And then we have, you know, welfare queens. Right. And Lonegan here was certainly in many ways, you know, any kind of thrown she had, you know, she lost and.

Speaker And she speaks out and she speaks out in a way which is the opposite of, let’s say, the way that Marian Anderson spoke out, that Marian Anderson spoke out in a very dignified way.

Speaker I’m actually going to try a different way into this anyway.

Speaker OK, so, you know, Marian Anderson was a an emblem of dignity for me, for many of us young black kids growing up.

Speaker And she became a role model for how one might be able to have one’s voice heard, how one might be able to be accepted, how one might be able to be heroic. And as a girl growing up in the 60s, still the model of that heroic ness was a very quaffed, contained individual who only did dignified kinds of things. And maybe it’s not unlike, you know, Martin Luther King’s behavior. And that was crucial at that time in our lives. Also that there was a way that it went along with the tradition, the black religious traditions, black spiritual traditions. And for even those of us in my case, I never saw Marian Anderson sang alive. But the very thought of this woman who had made it through great odds to bring this beautiful voice that sang these beautiful truths to us was important. But again, it was all in this very quaffed, contained, dignified behavior. And I was recently reading a manuscript of a African-American woman, law lawyer and scholar at Columbia, Patricia Williams, and she compares the queen leanness, the dignified creaminess to the queen ness or what became the queen ness of lannigan, the that she was a quote, a queen who then misbehaved. Right. Is that she spoke out. And the fact is in these times is very unlikely that anyone is going to be able to be effective by being, you know, this very contained, dignified individual. And we’re seeing more and more people getting in trouble for not being that right. You know, Anita Hill, even though she was quaffed and controlled, said outrageous things. Jocelyn Elders just this weekend, even though, you know, with the uniform and very quaffed and so forth, says, you know, outrageous things. And in a way, I think this picture becomes more valuable now in these times. I’m very glad that we have a photograph of Marian Anderson not saying outrageous things, but looking as though she’s enjoying herself, looking as though she’s enjoying, you know, the central in this of the experience of singing with her hair blowing free out of that cloth.

Speaker And even, you know, asymmetrical makeup in a way. You know, you can see the kind of sweat and liquid on one side. And and so there is not perfection. You know, that she’s not in the center of the photograph. It’s a little bit off center is great. And I think in some ways it must have been before. It’s time for him to have gotten that photograph of her and her jewelry, you know, very, you know, kind of big lush jewelry, kind of clanking off to the other side. I think it’s great picture.

Speaker But the Al Sharpton venture. What is that? No response to that. Is.

Speaker I have to say, I don’t think I agree with evidence idea about Sharpton. I know he’s probably right, but I’m not sure I agree. I wish I had thought to ask Sharpton because I’ve just seen him a couple of times recently. What he thinks of this photograph.

Speaker Cause if I recall correctly, when Avidan described the photograph, talked to me, he described it as a person who’s talking out of both sides of his mouth. And Sharpton might be doing that to some extent. But I think that Sharpton actually, remarkably for these times, speaks out of one side of his mouth. I mean, what he’s planning to do right now in response to the fact that a young boy in Staten Island was killed by a cop last summer and the grand jury has exonerated the cops. Sharpton is going to have a march down Fifth Avenue on the evening, five o’clock on on December the twenty third. Right down Fifth Avenue. Right. With the whole intention of disrupting one of the biggest shopping days of the year. And I was just on the radio this morning with him. And I think he actually speaks very boldly. Whether or not it’s effective is a whole other thing. I don’t really want to get into that. But I think he actually speaks persistently and boldly in in in one direction. You know, more than most people now, we might say that behind that, there’s another agenda. I don’t know. But I’m still impressed that he keeps at this thing of his marches. The comedian Joy Bay said the Sharpton. In this spoof of the Democratic conventions, the these comedians went around and asked people, unless conventions, you know, as though serious questions had to Sharpton. You know, Sharpton, you doing all these marches? How come you never lose a pound? Right. Very funny. Right. But he does this persistent march with one specific agenda, and that is to wake people up and to raise consciousness and to constantly try to make the world see things that are happening here, which many people want to dismiss at breakfast. So in that context, I have to say I disagree that he’s speaking out of both sides of his mouth, if that’s what this photograph is meant to do. Right. Or it’s actually it’s showing several images of him. I think everyone told me it was a mistake, actually, too. But what I do think is interesting is that the photograph.

Speaker Even though he doesn’t have both fingers pointed this way, he has one, two hands pointed this way, one over the other and one like this. It still does look like he’s shooting with two pistols. And I do. I think that Sharpton is shooting with two pistols.

Speaker How would the 60s photographs that showed you the ones you just want, that any reflections of what you saw and what you captured?

Speaker Well, I guess it’s maybe not unlike what I was talking about with Marian Anderson with which was that in every case he’s seeing behind.

Speaker Something right, he’s seeing in the case of Marian Anderson. I interpret it as he’s liberating her from the mask, which is put on her. You know, this mask of dignity, which was the only acceptable way to come forward. In the case of, say, the photograph of the D.A. are I’m sure that’s a situation where the D.A. are thought that he was capturing a mask and instead he’s capturing some women facing one way and others facing another way and not in flattering poses. And that’s, you know, revolutionary that he’s able to use his form and to use the fact that most people stand in front of the camera with with narcissistic wishes, you know, he’s able to use that fact to see more. And, you know, some people like it and some people don’t. In the case of the photograph of the D.A., ah, you know, I’m appreciative of it.

Speaker At the models face, any other photographs that stretch from the 60s that reminded you of when you were growing up, that was.

Speaker Those animals that well, Wallace looks to me like the scary, terrifying guy that I thought he was when I was when I was growing up.

Speaker What do you mean you going to occupy Dixie? I don’t know if if.

Speaker If he saw what I saw, I mean, I just saw a scary racist guy. Scary, racist, outspoken guy. I think what stands in my mind the most maybe I should look at it again is his hair somehow. If if I were to compare, you know, Wallis’s hair, say, to the hair of JFK. Right. It’s like very, um, giving hair or the hair of Marian Anderson. Right. You know, he doesn’t show us Wallace with his hair flying. He shows his Wallace with his hair.

Speaker You know, slicked back a cap on a man with a cap on.

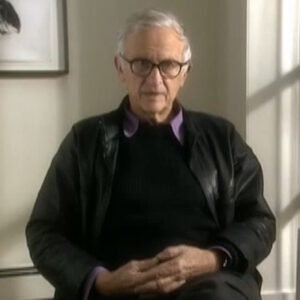

Speaker Finally, you spoke about the father series. We’re upsetting, powerful. Yeah.

Speaker If I recall correctly, when we saw the. Except that I felt that, you know, it was almost like, well, I mean, it was put together to look like everything was leading up to the fight of father photographs. Which is powerful, isn’t it? That in some ways, as we as artists meet ourselves, we have to meet our fathers. Our mothers and our fathers, and I guess, you know, in each case. We have different things about ourselves that we in the course of our work, both want to meet and want to avoid. And I felt that by the time we get to that last room, there is something that Avidan is accepting about his father and. You know, I’m not an Avidan scholar, and I don’t want to seem to be ignorant. Certainly.

Speaker Or. Or boring.

Speaker But there did seem to be an acceptance of death there and a resignation. Not an easy one, but a resignation.

Speaker To the to the fact that.

Speaker Our faces fall, and I don’t mean that in the way of of a beautiful face or not a beautiful face, because the exhibit also took us through Nantel wards, for example, but that ultimately the eyes will be revealed. And that what comes out of the eye, you know, is a. Window, you know, to eyes a window to the soul and maybe a window to something bigger. It looks as though I haven’t. I mean, I haven’t seen this that for those. Do you have a copy of those? Well, I mean, I think there’s something very profound ultimately about these pictures, I don’t know if I have the words for it, I. If I could rehearse the sound, I would have a sound, you know.

Speaker Stuff, you know, to friends whose fathers died this week and my father came to visit me this weekend.

Speaker Something like. You know, I would I would rehearse a sound like that, something like that. Which is about.

Speaker Pain and effort. The effort. The effort of. Living.

Speaker But that as important as the as a part of that effort is the silence, that is to say, the incomplete ID. Cry if it were. That’s one effort. But that what is interesting to me is up, which is that the sound is not complete, that the the absence at the end of the attempt is as important somehow.

Speaker And so that even though these photographs are about the end of a life. There still seems to be something unfinished, you know, because the mouth is at least in two of them, partially open and because the eyes do seem to be looking towards something. And I think that. It makes me feel something that I’m not able to feel every day about life and death and about meeting. My life about meeting.

Speaker The inevitability that death embraces all that life steps back from death, but death embraces all.

Speaker Something about that which I probably started thinking about as a little girl and through the process of my life.

Speaker Have to try to finish thinking about the inevitability that I probably will not finish thinking about it because I’m also only going to get up that much and. I guess the question of. Being ready for the moment and, you know, seeing the photographs of his father in a tie and everything as though, you know, he’s ready for something, and then the photograph of him not in a tie, but in a hospital gown, you know. Maybe that’s the readiness and also that in this year, I’ve had many people. Losing their fathers and losing others, and I’m more than one occasion. I have been told of the. Bedside visit as if as breath.

Speaker Stoppie.

Speaker You know, I always thought that when we die, it might be on an exhale.

Speaker But I’ve now gotten at least two reports of death on an inhale.

Speaker And just to stop.

Speaker So I would say that these. The pictures are part of my own consciousness of helping me to understand something about their. Painful pictures. Yeah. Painful, but beautiful in another way. I think I was saying I felt they looked like Avidan. I think he’s a very beautiful man. I’m not the only person who thinks that. And so they are painful because of the aging and the effort. And.

Speaker Kind of collapse and sadness that we see collapses maybe too strong of a word. But the wishing that we see, the longing that we still see.

Speaker But they are very charismatic. And.

Speaker I don’t know, maybe this is the wonderful Naess of having an eclectic eye as as Mr. Avidan has had is that he can look at. Fashion, he has a political point of view. Maybe it’s being able to take all of those things and ultimately create a vocabulary that allows you to look at something that none of us want to look at.

Speaker To give to endow something that none of us want to look at with charisma.

Speaker Incidental question I have for the show, the curious case Abberton, just from your short equate to a character that would be easy for you to create.

Speaker He would be very interesting. I’m actually looking for a man to do a very long piece with because I want to do like a 20 minute piece on Elaine Brown, the ex Black Panther. And I’m looking for a man about evidence age to a white male to do a long piece on. Maybe you can help me get an interview. What would you fall out of? I don’t know. I mean, we would just probably talk about his work.

Speaker His work and his life and. In the. He’s a very animated man. He has nice, loud, strong voice. I mean, nice direct voice. He seems very opinionated. I always like those kind of people.