Speaker What is the general consensus or what has been the general consensus about Rockwell in the art world?

Speaker I suppose it’s an unspoken consensus until very, very recently. He simply hasn’t been taken seriously or taken seriously. It would have been in a negative way.

Speaker That is to say, Norman Rockwell, like would conjure up a certain complex of ideas and attitudes that people found repugnant. It it there may hear a Narrabeen, somebody who admired him as as an artist, but for for them for the most part. He he wasn’t, I think, taken very seriously. Why? Oh, because the attitudes that. Well, there are a couple of reasons.

Speaker Were the the art world for a fairly long period of time was mainly concerned with.

Speaker With formal formulas, formulas, aesthetics and abstract painting, which showed formal relationships in a very perspicacious way. And although you can look at Rockwell Formalistic Lee, it’s not obvious that that’s the way to look at it. I think the second reason was that people do find, for whatever reason, sentimentality unacceptable in art, although there’s an awful lot of around, but not usually in the cutting edge galleries. By the cutting edge artists, I mean, there are plenty of paintings of clowns with sentimental faces that are sold. But that’s not the art world.

Speaker That’s the well.

Speaker That’s the world where people just buy paintings to hang over the fireplace. Then thirdly, I think since nineteen well, since the 60s at any rate.

Speaker Rock, rock, rock, well, was probably identified with certain Americanism and with the Vietnam War and and the rest of it.

Speaker There was a general sense that that in the art world, at any rate, that Americanism was in some way, I suspect patriotism was in some way suspect. So those would be at least three reasons why why people wouldn’t wouldn’t have given rock rock while the time of day. And so, so emblematic, I think Rockwell, was of what was perceived as American ism, that operatives were able to attack by parodying rock rock. Well, in the last year or maybe the Whitney biannual before an artist painted a copy of Freedom from Want, which is an old fashioned Thanksgiving dinner. And there is the beaming grandmother and everybody smiling and well-dressed and on the platter, instead of a turkey, there’s a pile of needles. And that was a political kind of comment on that. Not, you know, that idea of freedom, that idea of painting, that idea of family life, that family values and and the rest of it. So I’d say he he was under a fair number of moral political indictment’s, you might say, in in that period, despite his well, his his political courage, particularly in the later part of his career, when when he undertook to do those paintings about the South, etc. in the desegregation of the schools, though, those are very powerful and independent paintings. He certainly was not without criticism of the way the way things were run in this country. But for the most part, I think all of those were true in some way. But the attitudes toward them have maybe changed.

Speaker But as we were saying, when.

Speaker As well. Well, it does seem to be an air again. Do you think we’re in the midst of a revisionism, frankly? So why are.

Speaker Well, for one thing, formalism formalisms virtually dissipated as an anaesthetics for painting today. It’s not just that the figure is back, but that virtually everything is back. You can do anything and people will look at anything. Now, there’s none of that. Somewhat harsh ideologized formalism and hence abstraction doesn’t have the dominate, dominating impact on people’s sensibilities that it used to have. But beyond that, I think that there’s a lot of interest in what and what not. One might think of the popular R and Robert Rockwell was as a cover artist for a popular magazine, almost the epitome of a kind of pop popular artist. I, I don’t know whether to what degree the art world has come around. Not quite to that view. I have to qualify that.

Speaker I think there’s a reason why certain people in the art world have discovered Rockwell is because they’ve begun to realize what a marvelous painter he he was. I don’t think that the general resurgence in popularity of of Rockwell has got much to do with that because it’s relatively rare for anybody to seen an original rock.

Speaker Rockwell I, Bobby Rosenblum and his review of recent book mentions one in half at the Hartford Athenaeum.

Speaker I remember seeing that now some years ago and being knocked out. And I thought it was really imaginative to somebody of somebody who must have brought it up out of the basement, actually put it on the wall, because it was a very handsome, very handsome painting. The content was characteristically Rockwell. It was a little girl with a black eye sitting in a doctor’s office waiting to be treated. And he he liked to get tomboys in in that way. So if there’s a certain approval build into the painting of that that girl and he he was extremely, extremely good at communicating an attitude through the painting. But just in terms of the quality of paint, just the way the paint was on it, it it it it it was the touch of a real master.

Speaker But I mean, in terms of did he go over the edge, the sentimentality. And what’s often he did, he did one.

Speaker Well. He did what I think he probably made people feel better about themselves in the world than they had any right to feel. I mean, he did create a kind of moral myth for Americans.

Speaker You looked at the paintings and you felt, well, that’s me. That’s the way life is.

Speaker They could see themselves in those paintings. And at the same time, they were.

Speaker A little bit condescending. They felt that. Well, I can see that. So I’m a little bit superior to them, too, to talk to the people that these shows. And so there was a way of creating a bond between you and the people he showed and a way of giving you a sense of superiority, some somehow or other. It made you look on them with a certain indulgence. And this is in a period where, well, I mean, a good chunk of it was the thirties. It was a period of of of depression. There’s not a lot of that in Rockwell. Or if it is there, you get the sense that that’s a natural and normal condition to live in it economically reduced circumstances.

Speaker The famous one of the grandmother and the little boy praying at a table. Thanks. We’re in in an automat, probably. And then these two guys looking, well, almost like figures in a religious painting at something light like that. So they’re these are paintings of reconciliation almost to an economic condition, to hardship, to the need for thrift. That reinforced people in a certain kind of complacency, I think.

Speaker You wrote something very interesting.

Speaker I think you said that Rockwell’s painting wasn’t so much a reflection, a part of. You know, it wasn’t so much a part of a reflection of American reality as a part of us. I think I’m paraphrasing, but what a can. Mm hmm. Can you restate that? I think. Well, I think.

Speaker Let me try and restate that. I think that he wasn’t just reflecting the reality that he saw because of the immense popularity of the Saturday Evening Post. He was creating that reality because people looking at those covers, cutting them out even. I’m sure talk talking about them or internalizing the values that the covers that the cover is projected.

Speaker So Southern America in in those years was there are certain attitudes that Rockwell transmits certain affection for Boy Scouts, for Tom, for Tom boys, for some somebody said foxy grandpas and and so forth.

Speaker And at the same time, you see how people are living out their lives and in in not not not very up opulent circumstances. They’re not prosperous.

Speaker They have to sew garments instead of get get new ones and so forth. And you see people. Well, there’s a wonderful one. One that I like a lot of. I have a man looks like Will Rogers sitting on a running board of a truck maybe, or a car. And his son, who is much taller, is looking at the train approaching and he’s going off to college. And there’s a lot of stuff that’s, you know, definitely that he’s going to college. I don’t know if he’s got a tenant, but something that people could read and and people would look at that might say, well, I mean, that’s what life is. The son is leaving and the fathers faces careworn and lined with wisdom and experience. And the little face of the youth is just like a blank tablet. Life hasn’t written on it yet. And so people would say, well, he’ll learn sometime and and so forth. So it was very reassuring to people who were leading what are depicted as very normal lives, very natural, normal lives.

Speaker So you think there was an emotional reality to when he painted? Oh, sure.

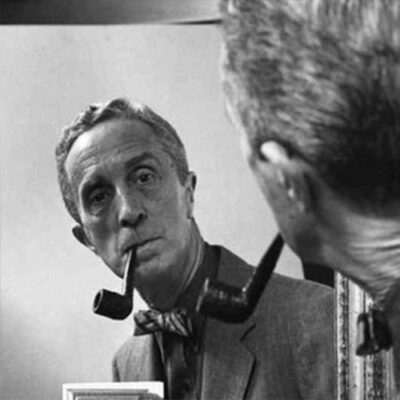

Speaker I don’t think there was ever anything that didn’t have an emotional reality that he painted, except on occasion when he is when he doesn’t cover a bomb. Ah, that’s not that. Those are usually very funny. He’s very he’s very articulate about art. When he paints artists, when he did his own self portrait, I mean, that is really a great self portrait. You could write a dissertation, the one where he’s leaning over with a pipe, that you could write a dissertation about that self portrait. When he he does a wonderful early one of colonial painter painting a sign, maybe it’s a sign for a tavern.

Speaker And and he’s he’s painting it as a colonial painting and that pun between the way Rockwell’s painting is and the way the colonial painter’s painting is. I think that it’s a brilliant contrast. It’s like a painting I love by the Baroque Artist Squared Cheena, which shows Saint-Marc painting the Virgin. And Guadagnino knew that Saint Mark couldn’t have painted like a 17th century Italian master. And so he invented an archaic style. And and then you get the contrast between the archaic style and Guo Chino’s style, which is quite clearly magnificent. But of course, since the purchase and the growth, China was never going to have that opportunity. It was that or the the marvelous painting about it, which I think was called a kind of sword. I don’t remember the titles always, but where a man is standing smack in front of a Jackson Pollock and studying the way a connoisseur my my might study some old old master. For one thing, Rockwell painted a Jackson Pollock. I don’t know how he did it, but he painted it in in a way that was totally convincing. And he couldn’t have painted it the way Pollock did using the whole arm. I mean, this is a risk painting. He has to have been a risk, a risk painting not withstanding. It’s very, very convincing. Pollock and it must have seemed almost an manageably funny that somebody should be sort of looking at a painting by Jackson Pollock with a reverence and attitude and concern that one would look at a Rembrandt or something like that. I mean, that that must’ve seemed terribly, terribly funny. I remember when it was many years after that painting. I went to the auction, the Andy Warhol auction, and was just painting of of Cy Twombly’s, which was a blackboard on which somebody in which he had written Oval’s like a penmanship lesson. And it it went for just under a million dollars. And I remember thinking this that was a cartoon in The New Yorker. People would find it very funny. That is to say that something that looks like a scrawl like that should should go for close to a million dollars or not. And I think that some of that wit or humor even was there. And and you feel as though Rockwell is trying to tell his viewers, you know, they think that stuff is pretty great. And the critics think it’s pretty great, but I’m not so sure. And you’re not so sure. So he was always on their side in that.

Speaker I mean, he didn’t. He tended to treat their aesthetic impulses with dignity and and respect by making this just a little bit too funny to be realistic, if you see what I mean.

Speaker He didn’t have flirtations with modernism himself. I’m in and out of one side of his mouth.

Speaker I don’t know the answer to that. He must’ve felt pretty embattled all of the time.

Speaker I was talking with, uh, with a sculptor. I know. And he he said that when he was going to Art, he’d gone to an exhibition of Rockwell that came up from Philadelphia to go go to that.

Speaker And he met Rockwell. And Rockwell took him through and he said he felt that not many people had gone to that exhibition, that he was that that he himself felt Rockwell felt numbed almost by the indifference of the gallery viewing public.

Speaker But I don’t think he made a gesture to do anything different because he probably couldn’t have done anything different.

Speaker It was so completely an expression of his personality. The other the other thing is that when the sculptor went back to school and and felt Philadelphians, there was a session where the teacher asked them what an artist’s interest. And yet you got the predictable one. I said, well, he was interested in rock while he thought Rockwell was a good art. And he said he felt like he was going to get lynched.

Speaker I mean, that was not an acceptable taste for an artist to have. So. So I, I, I feel that that it would have been very difficult for Rock Rockwell to make an adaptation to the kind of art favored by the kind of people who despised him. And I don’t think they could have taken it seriously. And I don’t know what it would have been like if he if he had done that because he was truly an old master. I mean, he he he truly if we subtract the fun and and some of the sentiment that he he had some of the qualities of a while in certain paintings like Vermeer, practically like the barber shop where you look into this darkened space and there is sort of room at the back illuminated and there’s a string quartet is some kind of music is being being played, the magnificent painting. And it it, uh, you feel as though he’s learned he’s learned from very how how to do that, how how to put people in a space.

Speaker And of course, the space is very vernacular. So it’s it’s it’s a barbershop, after all, not the kind of opulent Middle-Class Spaces with tiles and. Pottery, if I could marry you.

Speaker Oh, yeah. Yeah. People said there are other ways in which his painting comes out of the tradition of the Dutch masters.

Speaker It definitely does that. And there you do go. I’m sorry, I didn’t hear the question. I’m sorry.

Speaker It’s OK. Just being this definitely does come out of the tradition.

Speaker It definitely whether it comes out of the tradition, of course, is difficult to say, but quite, quite clearly it comes out of the tradition of Dutch painting, 17th century Dutch, Dutch painting, the little masters like like terrible and well, yarn steane. And those those wonderful, highly spirited painters that the Dutch bought in great, great quantity because they like the earthiness of a.

Speaker And they like the jokes in it. I don’t think Rockwell typically as an artist, I would call earthy. But he he he does like like comedy. And he’s always good, almost always good for a laugh. And that was very important. And in Dutch Dutch painting, they I can’t imagine Rockwell painting a couple of guys drinking at the table and well over the line of drunk drunkenness. Nor can I imagine any physical violence in Rockwell of the kind that a depiction of a peasant peasants fighting would have a certain uncouth violence.

Speaker Now there would be only the violence the fist fight would have among boys or between a boy and a tomboy. And I don’t know whether alcohol ever, ever makes its presence felt. There may be a personal explanation for that first, since his wife was and was an alcoholic and and he didn’t want to have it around.

Speaker But my own feeling is that he would have felt that it was inappropriate. On the cover of the Saturday Evening Post. And if he didn’t, the editors would have they’d say, where where the hell did that bottle come from, Norman? And take it out.

Speaker He quoted great painters and his work to think. Oh, sure. Give me a couple of examples.

Speaker He quoted well in the great self-portrait. I mean, for one thing, he’s got some of his favorite self portraits pinned to the canvas. There’s a juror and I can’t remember the others, but there are other kinds of thing. Then there’s the gold helmet on on top, which makes you think of a man in the gold helmet of a Rembrandt. I don’t think that’s entirely itself a self portrait. It is a lot like they’re a mirror. On the other hand, very mirror self portrait. What people take to be very mirror self portrait. Vermeer depicts himself from behind.

Speaker Facing an easel on. On which he’s painted the spirit of history. And there’s a model over there, a model who’s posing as the spirit of history. And she’s wearing laurel leaves and a blue garment. And and she has a manuscript. I think facilities is in in in her hand. Rockwells is his own model in this in this particular case. And he brings in a piece of apparatus that Vermeer doesn’t show, namely a mirror, which enables him to show us what’s on the face.

Speaker Vermeer doesn’t do that. We see he peeks around the pipe. And there’s that face and we’ve got that. So we know what the face is like and we can compare it with the face on the painting.

Speaker So there there are two appearances and one inferential appearance, and then we can ask ourselves, well, how good a painter is he? And then we say pretty good because he looks like his own mirror image. That is what’s on the canvas.

Speaker So I can’t think of another self-portrait beyond the great Vermeer self-portrait that that I can read in that.

Speaker As I say, it’s it’s self-referential. It’s about the act of portraying. It’s a it’s it’s a portrait which portrays portraiture. And so it’s a deeply self-referential work.

Speaker And those are the kinds of qualities one would think the avant garde critic would be deeply responsive to. But I’ve never seen an article in one of the leading cutting edge art magazines which which talks about Rockwell in terms which come very naturally when they when people talk about other artists in the forefront.

Speaker His other paintings about art, do you think he was working out for himself his own view of himself as an artist? I mean, once he an illustrator, was an artist?

Speaker No, I don’t think so. I don’t think he was worried about that. I think he had a lot of confidence in and his gifts and in his achievement. I think he did it the way he did everything else, holding certain mirror up to the world.

Speaker He took it for granted. His his viewers, his viewers would know what what was being alluded to. There’s a remarkable amount of pictorial literacy in American society.

Speaker People knew about Jackson Pollock very fast. He was talked about in about 50 years ago, I suppose, and nearly 50 years ago to the day in an issue of Life magazine where it said. Is this the greatest living artist or American artist that shows shows Pollock?

Speaker So in a way, I guess Rockwell had to take on the greatest living American artist by being the greatest living American artist at that point himself. And so there’s a little bit of a conflict there that he may have felt edgy about being an illustrator just just because being an illustrator through this period that we’re talking about through the period of modernism was a debated status.

Speaker And in the late 19th century, artists like to lose track was was an illustrator. Most of the American artists had been illustrators. Sock Hopper was was an illustrator. John Sloan was an illustrator. Robert Hendra was a nail. They were all illustrators. That’s how they made made their living. They may have thought someday I’ll just go on and paint the kinds of things I want. But I think he was so fulfilled through illustration that he didn’t.

Speaker He he. He. He must have been. It’s you know, it’s it’s really, really hard to say. But I don’t know whether it stung him to the degree that it would. If you think of a critic in the 1950s, the 60s saying, well, this is just illustration. Then it’s like this is just decorative or this is just literary. And those would be the kinds of things people people would have.

Speaker Well, I mean, is there a distinction between illustration and art?

Speaker I mean, if you want there to be there is obviously I’ve got a I’m sorry. You don’t had a question. That’s a question.

Speaker Is there a distinction between illustrations and. Ah. No, I don’t think so. But people thought there was a lot lot largely.

Speaker Largely because probably because of the association between illustration and in in a famous paper, the late thirties, Clement Greenberg called Kitsch. It’s not it’s not high art because it’s not primarily interested in basic formal compositional values. It’s art put to use.

Speaker And the idea of art being put to use would have been anathema, I think, to most most of the painters who were building up a self image. Of what? What painting was and what our art was. But I think that most of the painting in the history of Western art is illustration.

Speaker In the sense that artists are illustrating sacred texts or classical texts. And if you took away the illustrations, there would be very little art left. I mean, you’d have a few still lives here or there. And then a lot of what’s done in the 20th century.

Speaker But even even after all, Picasso did illustrations. He did these great books that shaped Dove. And Cornelian and Arvid’s Metamorphosis and so forth. Martys did a little illustration. It wasn’t all they did, but they did it. It wasn’t regarded as such a terrible thing.

Speaker So what does it on Rockwell’s work that seems to open him up to this?

Speaker The stain may be too strong a word, but I mean, it’s well, what what opens Rockwell up to the stigma?

Speaker You mean of of being, as we would say, just an illustrator? I think probably that he he didn’t do anything else that I know of. I mean, he may have done some some paintings on his own. I just don’t know that much about the non published part of his his life.

Speaker But but he he also, I think would be perceived as.

Speaker Endeavoring to be ingratiating to the viewer. And I don’t think a modern painter thinks of himself or herself as aiming at ingratiating the person who who looks at the painting. He’s always bent on ingratiating. He wants to be on your side by putting you on his side in that whole saga of comical situations that he depicted. And so there’s a little bit of a sense of manipulation, but that’s almost always true, I think. But that was not true of the other great sequence of cover art in this century. The New Yorker covers before the administration of Tina Brown when they were really great covers and where they were closer to what one person would think about art because they were gratuitous.

Speaker They had no connection with the content of the magazine. And yet there’s a parallel rhythm to Rockwell because The New Yorker transmitted a feeling of innocence in those covers. It was like a nursery school or kindergarten. That was always a Christmas cover, Easter cover. There was always a Thanksgiving cover. There was always a fall cover. And and it was like getting children. All right. We’re going to do the Halloween cover this Halloween paintings. This week, The New Yorker kept the holidays. And so and so did Rock Rockwell. So it was like maybe a book of ours. If you followed through the covers year, year by year, there’s a cadence and it’s the cadence of life. And and The New Yorker in those days for for what was meant to be the paradigm of sophistication in American in American letters was surprisingly not New York, like very much at all. It was more Connecticut, like if you like it, it projected a fantasy of how New Yorkers would like to live maybe in in the in the green land of Connecticut to the north.

Speaker And so it was bucolic and and and I guess maybe Tina Brown’s covers have managed to bring New York back into contact with its rough and cynical attitude toward life.

Speaker But you suddenly realize that something terrible has been lost with the change in covers and and.

Speaker The parallel, at any rate, with with with Rockwell and look at the magazine covers have all disappeared. They all look alike. Now, you always get the face of a pretty girl and a lot of print in this issue. Toenails. Fingernails. False eyelashes and so forth. The New Yorker never published words on it. The art was respected and there was just the space at the top where the logo with a logo went.

Speaker Now, there is no magazine like that. So I think in in in the years in The New Yorker was found, 1925. And I think that those years are also the years from then on. We’re also rock Rockwell’s great years and the magazines. I don’t know enough about the other magazine, but it’s as though they’re really respected, the art that was the front of them.

Speaker And now that’s just not so tall.

Speaker I want to go back to your point about Rockwell’s ingratiating quality, wrote at some length about that. I’d love for you to get into that sort of things. You wrote about a fountain dimension to Rockwell.

Speaker Yeah, I did write once about fasting. I mentioned that that that that that is to say, as though it struck a bargain with the devil of the art world that let me be popular and let me be really comfortable. And you can have my soul. I’m not so sure I think that anymore. And at the time when I wrote that in reviewing the collected the definitive catalog raised on a of of of Rockwell’s work, I mean, at the time I thought it was a bit screwy putting out a catalog race on that of Norman Rockwell. We all grow. We all change. And as I’ve begun well, as over the years, I’ve been evolving a certain philosophy of art that enables me in a way to look at everything and to like a lot of things that may be at that stage in my career. I wasn’t so sure of I wouldn’t I wouldn’t say that. I wouldn’t say that today. But what I do mean is that when I talk about ingratiating, enlisting the sentiments of the viewer, getting the viewer on your side, that’s not unknown in the history of art.

Speaker After all, there is. I was just with somebody staying with somebody over over the weekend. Nada.

Speaker Copy of Correggio Painting of the Magdalene, Mary Magdalene, Mary Magdalene.

Speaker And there she is praying to a crucifix. And there’s a big luminous tear coming down her face.

Speaker And that is addressed to viewers who want the artist, want them to feel a certain way toward Mary Magdalene, that beautiful woman who is crying over Christ crucified and pray for redemption in Guido Reynie. I mean, not us. I think it’ll be easier for me to to take on Norman Rockwell than Guido Rainey, although he was a marvelous painter. Same in other artists. Yes. I remember him saying I read him saying, you know, that he has a thousand ways of making a pair of beautiful eyes turn heavenward. And he did it. He did it. So you look you look at one of Guido Rani’s paintings and somebody pray. And those eyes are their beautiful eyes. Beautiful eyes.

Speaker And they’re turned up. And you you feel when you look at that, exhausted, I suppose, if you’re that kind of a person and and you feel dissatisfied with yourself, that you have doubts of a kind that that girl or woman doesn’t have. And and so that’s always been in in in Western art or at least from period to period in Western art, a genuine motive. And so the artist is is manipulating. But let me put it this way. Manipulating in the cause of piety and the cause of faith.

Speaker Whereas Rockwell is a little bit more cornball than that. That is to say, a smile, a chuckle at the foibles, the endearing foibles of the man next door, the boy down the street, the girl upstairs.

Speaker And he doesn’t reach for he doesn’t reach for what Hagel calls the highest ideals of mankind. And I think it’s both the restriction of his range and the transparency of the effort of ingratiating that that that makes you feel as though he is inferior, as a moralist, as a pictorial moralist to the people that he might be compared with on the grounds that they, too, endeavor to ingratiate.

Speaker Oh, Warhol drew his inspiration from the most ordinary of ordinary things, the refrigerators could have belonged to Rockwell’s kitchens. The objects would have been on the shelves of Rockwell’s kitchens. I don’t think Rockwell ever would have done a bathroom, but a cleaning fluids or powders would have been in Rockwell’s bathrooms. If he if he paint painted any.

Speaker And and I think that at that time at that time, the people in the art world, people who were painters, people who went to artist colonies, people who went to Woodstock when I was an artist colony or now to the Hamptons would have found American life pretty crass and crass and materialistic through the fixation on these ordinary kinds of things.

Speaker Canned soups, Brillo. And I think what what Warhol did was to make them make them make one realize how dense with meanings in terms of the roles they play in ordinary life. These these objects really out. You find that in in a fairly daring painting of Edward Hopper of a man in an isolated Mobil gas station. And there’s the sign of the flying Red Horse as it as it was called. And to take a piece of commercial reality and put it in a painting was pretty shocking for people. There’s a lot to be said. I think Hopper is closer to Rockwell than probably anybody else in American art because he really does paint ordinary hotel lobbies. He paints ordinary bedrooms. He paints ordinary restaurants. He he depicts people doing the most ordinary things that happen and lived American life in that period, which is coequal, pretty much with Rockwells, period. You feel, nevertheless, that from a human point of view. Hopper’s got a range which I don’t think Rockwell even dreamed of.

Speaker Loneliness and sorrow and desperation and fear and aging.

Speaker These are the fear of aging. These are not qualities that appear in Rockwell at all.

Speaker If he does, that old man really is a cute old man. If if if he does, people in restaurants like the woman praying it’s in the interest of moving the viewer.

Speaker I don’t know that Hopper was ever interested in moving the viewer. He was painting with his cold on inflected gaze on life as it as it really is. But it was the life that Rockwell depicted. I mean, it took its enacted transacted in the kinds of scenes that that Hopper painted.

Speaker And although we can look at Harper Formalistic, Lee was master of arranging plane of light, for example, against a wall or angle of light coming in. It is the deep human qualities that belong to a depth that in a way, I think Rockwell wanted us to forget, not think about in his paintings and why. I think you have to think of Hopper as a greater artist, maybe not a greater painter, because maybe him. And in a way, Rockwell had a lot more skill as as as a painter. But in terms of the human quality and the depth, hop hopper was was was was beyond anything that Rockwell, as far as I can make out on undertone. I read once the autobiography, Rockwell’s autobiography, and I’ve made an impression on me. I must say, I thought that that there wasn’t real intelligence in in that that book and a sensitivity one wouldn’t have expected. There’s a passage. I mean, it really struck me. He he is describing his youth and he’s invited to a swimming party at somebodies house. And he’s little bit late and he goes into the wrong bedroom.

Speaker There’s a bedroom for males to change and there’s a bedroom for females to change. And they’re there.

Speaker He’s wandered into the one women’s changing room and he sees all these garments lying around lacy, flossy, feminine undergarments. And he said it was almost as though he had a revelation that women are very different from men based on that experience up to that point. I guess he thought of girls as defective boys and a certain kind of way. And then suddenly he thought of girls as as a very different nature in order than than males are. And this was, I thought, a remarkably creative response to an embarrassing step. I mean, he derived a thought of some way, and I think it probably guided him from that point on in his relationship with women, but only I think somebody was with a kind of well, they’re almost philosophical intelligence might have seen seen seen this not prurient, but as a revelation. So I think in some way, I think Rockwell would have been capable or was capable of deeper thoughts than he put in in the cover paintings. And that, I think, is because the cover paintings are not supposed to be that deep. They’re not you know, they’re supposed to give you a smile. They’re supposed to be good enough to cut off and pinned to the wall. People did the same thing with New Yorker covers somebody. My wife was a cover artist for The New Yorker. So people were always saying, oh, I have all your covers. They’re all pen, you know, pasted up and and so forth. And I’m sure that throughout the United States, if you go into the old buildings, you’ll find Rockwell covers hung up. People really did like them. But as I say, that was because there were mirrors of what people thought they were without causing people to think.

Speaker More deeply than that, it held them pretty close to the surface. So the boy comes back from the war and it’s looks like a workers house in a factory town. And he’s a typical kind of skinny guy. He hasn’t been brought in by his infantry service, I suppose. And everybody’s waving welcome home, Willy. And there’s a pretty girl in a green dress. Around the corner, shy and and so forth. And we say now, isn’t that wonderful? I mean, it just. What a homecoming should be. And it’s almost as though the war was worth it for people to be able to come back. His pictures in the window, as I remember. And the little flag with the star on it, meaning one of our dresses in the armed services and so forth.

Speaker And and he doesn’t he doesn’t depict people saying, as it were, thank God he’s. Well, thank God he wasn’t killed. Thank God he’s not on crutches, thank etc.. None of that which a lot of people must have felt at that time. So he was celebrating. He was celebrating like birthdays and not really refract. Reflecting on the corrosion of aging and.

Speaker And. And the human preoccupations of aging and death.

Speaker And danger and politics, at least in the classical Saturday Evening Post. Tradition.

Speaker I just want to go back from a man who saw the advent of pop art will shift your view. I just didn’t get that on camera.

Speaker Oh, well, the advent of pop art. So I. I had a big impact on me.

Speaker Yeah, it. It.

Speaker It it was because of its celebration of ordinariness that made me think about the ordinary world in a very different way and not dismiss that as kitsch. But I think that those values are pretty deep.

Speaker And I thought that there’s probably nothing more powerful and moving than ordinary life itself. It’s what a soldier would dream about. It would be the content of a soldier’s dream, ordinary life, to be able to go to a soda fountain and those those days or hold hands with a girl and not have to worry about snipers or artillery and or dry dishes for your mother.

Speaker Those are the those would be Rockwell in themes and just the stability, the predictability. And I don’t know what the French call sunaj more of of ordinary life began to come through to me with with with pop art. And I hope that’s a lot more important than art could be.

Speaker And a lot of what made Rockwell seem significant to me was that he was almost the poet of ordinary of ordinary life. And I was willing to forgive him an awful lot because because of that. But I think more than that, I think Pop was the beginning of the fall of formalism.

Speaker Greenberg, the great formalist critic in America, didn’t do much writing after 1968 69 Pop. Really, its period of flourishing is about 64, 66, maybe ended by the 19 by 1970. But that was the beginning of the end. And then things begin to become highly pluralistic. And American are by the time the 70s is is over. It’s so pluralistic that you could do anything you wanted to as as an artist. You didn’t have to be a sublime painter. You didn’t have to be a minimalist sculptor. You could portray as your own face and any makeup you wanted through photography, you mixed media, you’ve got involved in performance. There’s nothing you couldn’t do as an artist. And I think that pluralism, which is the defining condition of contemporary art, but not pluralism, made Rockwell acceptable and in a way that you couldn’t give any of the previous reasons for for turning them down.

Speaker And I think that the. Hee, he.

Speaker I mean, if you’re going to take Saul Steinberg seriously, as I do, you’re gonna take Crazy Cat seriously as I do. If you can even take Disney seriously, then there’s no real reason not to take Rockwell seriously enough and to think about them critically. To be sure. But to give him the respect I think that one wants that an artist would would want. So I think he’d find a lot of he he’d find a lot of support in the art world if he were to come back. I mean, he would feel all right. I mean, I know my limitations, he would say, but they’re beginning to accept me in some way. Maybe they could accept him only because they accepted everything and he might not especially like that, but they would accept him. And people will teach courses in him and people will write theses on him. And I mean, he’ll he’ll have all of the post mortem success of a successful landing.

Speaker Are there any parallels to be made between Rockwell and people like Rauschenberg and maché other. They deal with ordinary things. Oh, no.

Speaker Between. Is there any parallelism between Rockwell and Rauschenberg? No. No, there really isn’t. It’s true that Rock Rauschenberg put into his paintings, the kinds of things that you’d find in a garage. And even I have written about him or even the floor has a painting, has almost an oil stained quality. It’s scruffier and so forth. But now he’s much more ambiguous. It’s much more difficult to make out what Rauschenberg would be about. It’s never difficult to make out. At least for the first three or four or five stages. Maybe there isn’t anything else. What Rockwell is is is about. He doesn’t have he doesn’t have an analog in in contemporary art. After as I say, Hopper, it’s really difficult to think of anybody that would would come close. I mean, you could take Martys not formalistic Lee speaking, but Martys and the period when he’s down and Neace again. Twenty five. Nineteen twenty five. Those are not what I think of as deep portrayals of the human condition. I mean these are. Hotel bedrooms, but not like Hopper’s hotel bedroom. They happen to be hotel bedrooms. And you can see through the window past the grille to the Mediterranean. He’s a niece. And they’ll be a model posing and there’ll be some Oriental throws and maybe a picture on the wall and some flowers and a vase. I mean, there’s no if it’s about a what, what, what, what my is called in the name of one of his early paintings looks kind of a fully luxe, luxurious piece and beauty about that. That’s what they are. Yeah. We would we do regard those as great paintings, even though they don’t have a lot of depth. I think with with rock, rock, rock, well, they’re not deep, although that kind of painting that he use, that kind of.

Speaker Perfect pitch. Representation of Objet. That’s the kind of painting in which deep truths can be presented. And he presented shallow.

Speaker So he fell short of what he could have done.

Speaker No, he was perfect at what he did. It’s only that when you start making those comparisons, you start asking, well, why is suspiciousness about rock, rock, rock? Well, no. He was a perfect cover artist. He belongs to the history of American car. And he he really did for a long time define what it meant to be an American.

Speaker And if we don’t define ourselves that way now, that might be our loss. It was an age of innocence. At least if you looked at the world as depicted by Rockwell.

Speaker Let’s cut.

Speaker Right. Uh.

Speaker He does seem to be a natural candidate for. What Walter Benjamin and a rather famous essay of an essay embraced, one might say, by the critical avant garde in this in this country called the work of art in the age of mechanical reproducibility, reproduction, and in in the sense that these these covers any any given one week would have been impossible if they didn’t exist in large numbers to reflect the circulation of the Saturday Evening Post. The New Yorker.

Speaker And it’s a great period would publish 500000 and they would be all there would be all over the place.

Speaker So we’d be like this great mirror that everybody they were part of life just because there were so, so, so, so many of them in the in in in the in the end, Benyamin.

Speaker So he’s talking course about the Nazis. And he says how they’ve turned art into politics. And he said when the proletariat responds by turning politics into our rock while did that. He certainly turned politics into hard. But it was the politics of everyday life. It was the politics of peace. It was the politics of Small-Town life. It was the politics. Leave us alone. It was the path that the politics of every man and every woman. And it was, as I say, a celebration of normal life. And I don’t think that quite was what Benyamin would have would have meant. But it’s perfect candidate for the work of art and in in the age of mechanical reproduction. The trouble was that. That Benyamin was thinking primarily of photographs and thinking of photographs as something which can be issued in indiscernible copies, one after the all.

Speaker I mean, in simple terms, those art for the masses are aimed at the common man. So that’s right. Maybe I could just restate it.

Speaker I think that sometimes you get the feeling you’re Benyamin is talking about.

Speaker I’m sorry, without referring to Benjamin, there’s nobody is really going to know who that was, I thought. So what are we doing? Just driving state in very simple terms. Oh, OK.

Speaker So I. I think that the 30s especially.

Speaker What was a period in which there were all kinds of.

Speaker Powerful, critical political philosophies in the air. And coming from the dictatorships, from the Soviet Soviet Union and elsewhere. And these critics, these these were criticisms of American politics, of democracy, of the common common man.

Speaker And I think that what.

Speaker Rockwell did.

Speaker Was to assure the common man. You’re OK. You don’t have to change anything, basically. And I think that if we put it in the context of the horrendous political forces of the era, that was almost heroic stand. I think that that turns up in a lot of movies in that period to which are celebrations of the ordinary man. I don’t know.

Speaker Mr. Deeds goes to Washington or whatever the name of that film. But Capra film what? There’s a lot of parallels between the really popular movies like Frank Capra would have done or what’s the one with Jimmy Stewart, the shown year after year at Christmastime.

Speaker You know, the guy who who does the work or as our president used to say, levels the playing field and so forth and so on. He works in a bank, all these family values and so forth, and he thinks that he’s never lived the life he should have lived. And then suddenly the film makes us realize that this perfectly humdrum life was genuinely heroic and under the circumstances really, really is a hero. And that that’s the way to live your life if you want to be a real hero.

Speaker I think that Rockwells is the same message. And so he wants people to feel pretty good about themselves.

Speaker And so it’s easy to be critical and and say, well, I mean, he he doesn’t talk about the suffering. He doesn’t talk about the desperation. People without jobs and people having to leave arms in the Dust Bowl and so forth and so on.

Speaker But if we put it in that larger context, the context of reassurance, then he was reassuring people who were in desperate need of reassurance and that their lives were OK.