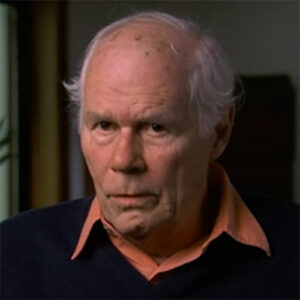

Michael Kantor: So what was the genesis of West Side Story, that Jerry Robbins had one idea, but then later got dropped? How did you and Lenny pick it up?

Arthur Laurents: This is such an old story. Jerry Robbins came to Lenny Bernstein and me to do a contemporary version of Romeo and Juliet. One or the other was to be Catholic and Jewish. I forget which. And what finally happened was I realized it was baby’s Irish rose set to music. Those who don’t know what the Irish Rose was, which I imagine is everybody. It was an enormous hit in the dark ages with a Jewish girl and a Catholic boy. Yeah, that’s right. And so we dropped it. And then some years passed. And Lenny and I happened to be in glorious Hollywood at the same time at the glorious Beverly Hills swimming pool, believe it or not. And there had been Chicano riots. Los Angeles, and juvenile delinquency had sprung up in the country. And talking about that, I realized that could be the show. And Lenny got all excited. He wanted, you know, because he loved Latin rhythms, and he wanted to do Chicanos. But I said, I don’t know anything about them, but I do know about Puerto Ricans in Harlem, because I was born and brought up in New York. And Jerry was all excited, and we went to work. And a hundred years later it was produced.

Michael Kantor: There’s a story, the story I’m fishing for is you were at a party.

Arthur Laurents: Oh, that story, yes. Well, before West Side Story came into being, I was going to, I had never done a musical. I was gonna do a musical version of James Cain’s novel Serenade, which Lenny was interested in doing. And then he dropped out and a fellow named Steve Sondheim auditioned for me. He played the score. A musical he had written called Saturday Night. And I told him I thought the lyrics were beautiful, brilliant, I wasn’t mad about the music. And that was the end of that. And then we were looking for a lyricist for West Side Story and I remember going to, this doesn’t interest you but I’m going to sell it anyway, to see a play called Isle of Goats with Uta Hagen. Where she, well, let’s cut to the chase. And they went to the opening night party afterwards and there was Steve. And as he tells it, and it’s true, I literally smote my far and said, my God, you are, I didn’t think of you. You’re perfect to be the lyricist. So I introduced him to Lenny. They hit it off. And that’s how darkies were born.

Michael Kantor: What about the fact that this is your first music, and here you’re taking on Shakespeare, and the issue of language there. How did you decide, how did you deal with the language?

Arthur Laurents: I think I had the toughest job because I was competing and they weren’t, and I thought the only thing to do was to look at the play from the story it told. And the language, one of the producers at that time she later walked out was Cheryl Crawford. She kept sending me notes that should have phrases like that’s how the cookie crumbles. So I said, by the time this show gets on, nobody will, they’ll have stopped saying that. And I thought the thing to do was to make up a language that sounded real and wasn’t. So I invented words like frabba jabba, which means, maybe not on PBS, but which means bullshit. And made it timeless. It’s also curious, I use the word cool which had been around with not much meaning and that gave it a meaning and it is timely to this day even though what cool means now isn’t precisely what it meant then. I think that’s a word that will always sound alive. Some of them are just dead, you know, groovy. Although that’s back, but I think not for long.

Michael Kantor: At the time that Lenny worked with Steve, he made a very magnanimous gesture, didn’t he? That was sort of underrated.

Arthur Laurents: Oh, you know, if there was an ego contest, it was between Lenny and Jerry, but Lenny made the most magnanimous gesture I’ve ever heard of or come in contact with in the theater. When we opened in Washington, Steve wasn’t mentioned in the reviews. We had all done something, so we were known, and he was absolutely ignored. And the Lyric Credit read by the two of them, Lenny and Steve. Steve had done most of them. Certainly the good ones. And Lenny said, look, this doesn’t mean anything to me, and this is your career, and I will remove my name. Well, that’s unheard of, but he did it. I mean, at the same time, we were on television in Washington, given the key to the city. And the man who presented it, not Steve, Steve was not asked because Steve was nobody. Our times have changed. Anyway, the man said, the key of the city is being presented for what this show does for juvenile delinquency. And he said, that was your idea, wasn’t it, Mr. Robbins? Your conception and Jerry said yes. Well on television, you don’t say wait a minute here. Afterwards I did and I had known Jerry for. 10 years. Lenny had known Steve just the time it took to write the show. So I said, obviously they think conception means this use of juvenile delinquency and gangs and Puerto Ricans and blacks. And I think you should remove your name. He said, let me think about it. And the next day he said, I’ve thought about it, you’re right, but I won’t do it.

Michael Kantor: So he’s exactly the opposite of money that way.

Arthur Laurents: He was an informer. Not a coincidence.

Michael Kantor: What about their egos? They both have huge egos, but how are they different that way?

Arthur Laurents: Lenny was like a child, Lenny was extravagant emotionally. He was just. One-on-one he was marvelous, and he was just outrageous. Jerry was serious. He wanted it. He wanted big. That’s why the credit meant so much to him.

Michael Kantor: And how did Lenny feel about Jerry? How did they work together?

Arthur Laurents: When Lenny died, I ran his, or MC, whatever you want to call it, his memorial at the Majestic Theater. And when I introduced Jerry, I said, Lenny was only afraid of two things, God and Jerry Robinson. Lenny is terrified of Jerry. I mean, during the out of town, Jerry would arbitrarily cut. Some of Lenny’s music. Lenny would start to get out of his seat, and then he sat back.

Michael Kantor: What was it that Jerry was striving for? Why was he cutting music without talking to his collaborators?

Arthur Laurents: Because it was for his ballet. And he wanted to cut the ballet, he didn’t ask, he just did.

Michael Kantor: So was he not concerned with the dramatic flow or the…

Arthur Laurents: He was concerned with his dramatic flow. He listened. The man was brilliant. And when we were writing the show, it was a wonderful experience. The moment, nobody knew what was going to happen. We were just amazed. I thought it would run three months. And the reception of Washington was so enormous, we were all knocked out. And that’s when Jared became Jerome Robbins. Einstein’s music was different from anybody who has ever written for musical theater. I think he wrote the most exciting theater music of anyone. I thought that the first time I was in the Army and I went to see On the Town and when I heard that music I almost jumped out of my seat. It’s the, to me, the one thing that makes that show exciting. I think it’s the most excited thing about West Side Story is his music. It’s pure Lenny, it has a vitality, an energy, an originality, and it is, it says America to me. It just is.

Michael Kantor: Game X and West Side and casting, it’s not an easy show to cast, was it?

Arthur Laurents: Well, you really couldn’t cast West Side. It asked for too much. Not only did they all have to sing, dance, and possibly act, they all had to be young. And the music was very demanding. The dancing was very demand. The acting would have liked to have been demanding, but I had to take what I got. Larry Currie, who played Tony, actually had been auditioning over and over for riff, but we couldn’t find a Tony, so he ended up playing Tony.

Michael Kantor: Carol Lawrence, I think, auditioned a dozen times.

Arthur Laurents: So she says.

Michael Kantor: What about, how did Jerry Robbins take these young performers and work with them?

Arthur Laurents: Jerry Robbins is notorious for being… Oh, what’s polite? I don’t know, Pharaoh with the Jews. He was, he beat the shit out of them. But they worshiped him because he was good. And his problem was he was inarticulate. The work he produced was brilliant, and they wanted so much to work with him. It’s interesting to me that Cita Rivera, who nobody praises Jerry more than she did, and said this was her chance and she was so grateful. Actually all her choreography was done by Peter Gennaro, but Jerry came in and applied the finishing touch that made something that was just shining sparkle and dazzle. Only he could do that.

Michael Kantor: In terms of your book, what was the most important?

Arthur Laurents: The one thing in the book that I’m most proud of and all the English critics picked up on it, the Americans didn’t because they’re not as knowledgeable about Shakespeare, is that I improved on Shakespeare in one place and that was the motivation, the reason why the message doesn’t get through. In Shakespeare, there’s suddenly a plague. And the messenger can’t. And with what I did, the message can’t be delivered because of the theme of the show, of prejudice. That’s what stops Anita from delivering the message. Anita being the nurse in Shakespeare. I’m very proud of that because it made sense. I also didn’t have Juliet, Maria, die. Because I didn’t believe that girl would. She was too strong. I mean, they always expired, but the vapors, you know, in Shakespeare was considered beautiful. But I just didn’t think that girl

Michael Kantor: Steve Sondheim’s quoted as saying, instead of writing people, Arthur wrote one-dimensional characters for a melodrama, which is what West Side Story is.

Arthur Laurents: Yes, I told Steve that I thanked him for the insult. And I do think it’s an insult. And it’s not true. They’re not one-dimensional characters. It is not a melodrama. Steve has never liked West Side very much.

Michael Kantor: In this same quote, he talks about it, lacking emotion.

Arthur Laurents: The thing is full of emotion. And I’m not going to get into, because he’s one of my closest friends. But I think that he’s a very, very good friend. Denigrates West Side. I’m not going to say why.

Michael Kantor: Well, he was very young at the time, wasn’t he? It was his first. And in terms of…

Arthur Laurents: He didn’t say that very young. He made that statement in his book, which you read. I got so angry when I read that stuff.

Michael Kantor: Well, what I’m referring to is why he doesn’t like his work. I know, you know, the… Parts of the show.

Arthur Laurents: But if you turn it off, I’ll tell you why.

Michael Kantor: Okay. How do you think the show, how did the show break new ground?

Arthur Laurents: I don’t think West Side broke New Ground. I think we took all the advances that had been made in the musical, put them all together and did them better than anyone had ever done them. There was one area where we did break New Ground and that is in the subject matter. That was the beginning of it being okay to die, to be raped, to to be murdered in a musical. But the techniques had all been used before.

Michael Kantor: What do you think someone like, what would George Abbott say about it?

Arthur Laurents: Oh, I know what George Abbott said about this show. George Abbott was responsible for getting this show produced because he didn’t like it. I will explain that paradox. We, when we were trying to get a producer, we wanted Prince and Griffith to produce it. And they had been brought up by George Abbot. George Abbots was God. And they gave him the book to read. He said, it’s no good. So they turned it down. Then Cheryl Crawford was to produce with Roger Stevens. Roger Stevens was a real gent, and he stood by the whole time. But he was not an active producer. We needed somebody else. Every single producer turned it down. And then Cheryl walked out on it. She, too, said the book was lousy. And she said Roger agreed with her. Well, he had told me she was going to do this. So I got up on a very high horse, and I thought, Cheryl, you are an immoral, indecent woman. Out I walked. The guys walked out with me. There we were on 44th Street. It was a sunny day, and we decided we’d go in the Algonquin and have a drink and decide what to do. And I couldn’t get in because I didn’t have a tie on, completing my triumphs of the day.

Michael Kantor: Here’s the age-old question. Is West Side Story an opera?

Arthur Laurents: No, it’s not an opera. Ned Roram. Really wrote an essay about the big difference. The big difference is very simple. It isn’t a question of singing all through. They do that in Lloyd Webber’s stuff. It’s a question of what kind of voice the music is written for. Operas are written for operatic singers. West Side was not. It’s that simple. People always try to complicate things. They count the bars of music and say, oh, it must be an opera. They never shut up.

Michael Kantor: What about, what was the original balcony scene? It changed, didn’t it?

Arthur Laurents: The original balcony, the song in the balcony scene was One Hand, One Heart, which I objected to. I thought it was too pristine. And Lenny and Steve said, well, it should be. I said, no, they’re young, they are hot. And it should hot. Well, it stayed that way until Oscar Hammerstein came to a run through and he said, that’s the wrong song. Then they changed it.

Michael Kantor: And what did they change you to?

Arthur Laurents: They changed it to tonight, which isn’t exactly hot, but when I redirected it in London for this thing. Harding could sing, their tongues were so running for each other’s mouths.

Michael Kantor: In a way, the love story in the show is couched in something that’s really American, which is the story of other people coming to this country, isn’t it?

Arthur Laurents: You mean all about emigrants. That’s something that has made the show, makes the show more timely today than it was then. When the word immigrant is said on the stage today, you can feel a whole audience freeze because of all this, I won’t characterize it, stuff going on in Congress about immigrants. It’s a nation of immigrants which we are very busy trying to deny.

Michael Kantor: Finding a theater, and then it wasn’t a huge smash initially, was it?

Arthur Laurents: No. I have to use a censored word, I’ll try to get around it. When we finally got the thing on, and Roger Stevens had a, he came from the world of real estate. Roger Stevens came from the world to read.

Arthur Laurents: Real estate.

Arthur Laurents: And he had a partner named Bob Dowling, who owned several theaters. The theater we wanted was called then the ANTA. It’s now the Virginia. So Roger said, oh, we’ll get that. And Bob Dowling said, I wouldn’t give a theater to that. You can fill in your own word, opera.

Michael Kantor: Here’s the frame. Do you have a favorite song or favorite part of West Side Story?

Arthur Laurents: Yes, the taunting scene, where they almost rape her. I think, uh… Everything comes together in that scene and it’s brilliantly done and it is very moving and it never fails.

Michael Kantor: Do you think the film, which do you think is better, the play as a musical or the film?

Arthur Laurents: That’s a very easy question to answer. I think the film is bad. I didn’t buy it for one minute. And I think that the reason is Film, literal film, celluloid, is either real or surreal. In the theater, nothing is real. So you can have boys doing the tour jeté down the thing, and then you accept it. When these boys came tour jetén down the city streets in New York, I said, not in this life. And then they’re all dancing in pretty colors on the rooftop. To me, it was phony from start to finish with one exception. Cool, which Jerry did and did for the camera, is done cinematically. The rest of it, I mean, they’re there with their dyed hair and. Heavy makeup to make them look Puerto Rican. Sheer balls.

Michael Kantor: Set up, what, what hap-

Arthur Laurents: And they also rearranged the scenes. They were so smart that they screwed it up.

Michael Kantor: But set up cool for us. What’s happening? What leads into that scene? What’s that song about?

Arthur Laurents: The song is about the life they lead which is they can’t show that the police or any adult gets to them. It’s very angry and it’s very tough. And interestingly enough, it was a brilliant dance which never got the hands it deserved until this year because Alan Johnson, who restages Jerry’s stuff, took the ending that Jerry put for the New York City Ballet and put it into the show and added something to it, and now it gets the hand it deserves, which is very gratifying because the kids worked their asses off in it.

Michael Kantor: What about it went through a number of title changes to?

Arthur Laurents: No, it didn’t. It was called East Side Story when it was supposed to be the Jewish and the Catholic thing. And then when it changed, I said West Side Story. And along came George Abbott. He said, that’s not a commercial title. So kidding, I called it Gangway. Oh, they said, That’s wonderful. And I don’t know how somebody came to his senses. But it was on the back of the original scenery. It’s painted gangway.

Michael Kantor: It wasn’t like, these are the guys, they’re gonna do it. David Merrick started, right? Wasn’t he the force behind pulling together everyone?

Arthur Laurents: David Merrick had the rights to Gypsy. I found out later that Betty Comden and Adolf Green were writing it. I didn’t know that till long after. I don’t know what happened there. Then Leland Hayward came in because he had Jerry. Jerry and I were not on the best of terms, but he said he would only do it I wrote it. And Leland asked me, and I read Gypsy’s book, which was very amusing and didn’t interest me. I didn’t think anybody would be interested in the striptease queen of America. So Leland, who was very expansive and expensive, he took me to lunch at the Colony three times. Said, oh, you’ll think of something. And what happened was I lived a lot of the time in a house on the beach in Quah. Everybody drank a lot in those days and a whole bunch of people sitting around. The conversation was about who was your first lover. And this girl said, well, my first lover was Gypsy Rose Lee’s mother. I thought, oh, well. There’s some more to that story than I thought. That’s how I got into it. And then I wanted Steve to write the score And Ethel Merman’s agent did not. So she did not. And Jerry Robbins proposed Julie Stein. Well, all I knew about Julie Stein was these pop tunes, and I knew the musical in my head would demand more than that. So I’m a little embarrassed to say this. Jerry had Julie audition for me. Well, Julie. Came in, I’d never met him, and I tell you, it was love at first sight. He was. I think he was the most adorable person I’ve ever met in the theater, and funny, and much more talented than I had thought. And when we were writing the show, he and she would write a song and they’d come down here and Julie would hold the sheet music up and say, may I say another hit? And he’d toss it on the floor and I’d say, well, he said, what? Be specific, so I told him, went back, next day, may I say another hit, and it was. Anyway, so that’s how, and then we convinced Steve. Steve didn’t want to do, you know, he was dubious about doing West Side Story because he, like everybody else in this country who is crazed on the subject of age, he wanted to have his first score on Broadway before he was 30. The chariots were galloping apace. But Oscar Hammerstein convinced him to do West Side. Same thing with Gypsy. And Oscar convinced him it would be good for him to do it. And he was brilliant. And they were a brilliant combination.

Michael Kantor: How is Jerry Robbins different on this show than on my side?

Arthur Laurents: He wasn’t involved. Jerry saw this show as a panorama of show business, vaudeville rather. He was in London doing the London Company of West Side rehearsing it. And Steve and Julie and I wrote the show very quickly, alone. And with scarcely panorama of Vaudeville. I think Jerry’s first contact with it was Steve and I went over for this, West Side was opening in Manchester. And Steve played him, Everything’s Coming Up Roses. And we looked there, you know, I thought this is really a knockout. Jerry scowled. He didn’t like the title. He said, that’s her name. Everything’s coming up roses what? Well, there you are. Anyway, um. Because he still clung to this vaudeville idea, they hired an awful lot of acts, burlesque comedians, jugglers, and they had to pay most of them off with a two-week salary. They also insisted that I write a burlesqued show. So I said, Jerry, unless Rose or Louise, who turns out to be gypsy, is on stage, they’re not gonna pay any attention. But I wrote it. As dirty as I could make it, and was cut.

Michael Kantor: So if Jerry wanted the show to be about the panorama of vaudeville, what was your show really?

Arthur Laurents: My show is about the need everyone has for recognition. That’s what everybody in the show has if you look at it. I know it seems to be about parents living their children’s lives, which it is. Children turning into their parents, which is also true, but what drives them all is that terrible need we all have for recognition. I began with the end, because I realized Ethel Merman was going to play the mother. Gypsy Rose Lee has to strip. Ethel has to top that. How does she top it? Well, she has to trip. What in God’s name would make her strip? In her head. Her need to be bigger and better than her daughter. Once I had that, then you just work, start from the beginning. You know where you’re going. And that made it comparatively easy. I wrote very fast. Some of it was based on things that I was told about. The original Rose. For example, there’s a scene in the musical where she packs her whole cast into two hotel rooms and the hotel manager wants to throw her out. And she screams rape and gets rid of him. Well, the story I was told was that she pushed him out the window and killed him. True or not, but it was a good beginning.

Michael Kantor: How much work did Gypsy herself, the real Gypsy, do with you all? Was she a factor?

Arthur Laurents: I think she was allergic to the truth. I would go see her and say, where did you get, tell me something, where’d you get the name? She said, oh honey, I’ve had 14 versions of it. Yours will probably be better.

Michael Kantor: How much of the Gypsy story is based on what Gypsy actually told you and how much does it actually reflect their life?

Arthur Laurents: There are certain things in the Musela that come from Gypsy’s book. For example, she liked animals, that she was born with a call, that she became a stripper. I could not get the woman to tell me anything that I could use. She was vague about her mother. If you read June Havoc’s book, she tells about the mother and gypsy giving lesbian cocktail parties. Well, that was no help to me. I mean, you couldn’t see that number. But I had to invent and just invent this character.

Michael Kantor: You mentioned, you know, initially that woman telling you about being Mama Rose’s lover. Is there, what’s the lesbian element in the musical?

Arthur Laurents: There is none. I didn’t think it had anything to do with anything, certainly not with that. The focus was this woman driving her children and thinking she’s doing it for them, but actually not. There was an interesting thing that happened. Mary was not the brightest. She once said to Jack Clugman, who was our leading man. Is Tapp Hunter gay? He said. Is the Pope Catholic? She said yes. As I say, she wasn’t as grift as… In Rose’s turn. She was supposed to face the fact that she had done it all for herself. When we got before an audience, we realized that she didn’t. So I added to the last scene a line where she said, I guess I did do it for me. Before I agreed to do the show, I had never met Ethel Merman. So I wanted to meet her. And we met, we had a drink. I remember she ordered a horse’s neck. I wasn’t quite sure what that was, but I knew it was non-alcoholic and I realized she was impressing the playwright that she was a serious actress and not a jazzy musical comedy lady. But I said to her, this woman is a monster. Are you willing to play that? She said, I will do anything you ask me to. And she did. I would write in the stage directions, slow, fast, loud, soft. And that’s the way she acted. So it says here, loud soft, that’s what I do. Well, when it came to this thing about saying, I guess I did it for me, she balked. She said I’m not gonna say that. That makes her a monster. So I think it was Jerry said to her, But you say it in the song. She said, no, I don’t. I say from now on, it’s going to be for me. And she was absolutely right. She came through and she did it.

Michael Kantor: Acting ability wasn’t that, you know, in musical theater at the time, acting ability wasn’t t as important as…

Arthur Laurents: No, I think if Ethel Merman did Rose today, she would not come off too well. Now, there are fans who are going to write angry letters saying, how dare you? She had a terrific voice. She was very right for the part, because she was brash. She was common. She wasn’t too swift, and Rose is not too swift. And she was determined. There were two things that Merman acted. Brilliantly, and I guess because they meant so much to her. One is she has a limer, she says to her daughter, and you are going to be a star. She said that with such ferocity that you could see. That was what drove her. And another was, before she does the strip, she’s talking about doing it in front of the men. She says, you make them beg for more, and then don’t give it to them. When she said don’t, give it She tore into it with such malicious glee that I realized, oh, she’s got her problems with men.

Michael Kantor: There was a nickname for her, wasn’t there? At that point, I think Steve Sondheim came up with a nickname.

Arthur Laurents: The talking dog, Steve called her, because she did a lot of things by rote. She said, watching Ethel Mervynor is like watching a movie. It’s always the same. And that was a trouble. It was frozen. And a real actor, the performance is never exactly the same, but of course when she sang, you know, there it was.

Arthur Laurents: How would you describe that voice?

Arthur Laurents: Trumpet-like as everybody else says, very brassy and with that little hitch in it. Small world shows to things like that.

Michael Kantor: Do you have a favorite lyric? Mine is some people sit on their butts.

Arthur Laurents: Favorite lyric? No, I don’t have much favorites of anything. Well, I think one of the things that surprised me most in that show was how wonderful the harmony is in If Mama Got Married. It’s just terrific and brings the house down.

Michael Kantor: What was Julie Stein’s special gift?

Arthur Laurents: The way some people sweat, that’s the way melody poured out of Julie, and enthusiasm. He was the most enthusiastic person I’ve ever encountered. But as a writer, he never had a, melody was just, it just, you know, everybody else, not everybody else. I mean, there’s Irving Berlin, God knows, and Dick Rogers, but Julie, the melodies, they’re effortless.

Michael Kantor: He was also sort of a broadway type, he liked to gamble.

Arthur Laurents: Oh, he liked to gamble. He came into this house one night, you know, rang the bell, came in, slammed the door, went up, running down the car. I said, what is it? He said, they’re after me. They want to break my legs. Got 20,000? He was always in debt. He was a real gambler. Very natty he was. When we were in Philadelphia, Jerry cut little lamb without asking Julie. He wanted it was a big number with a lot of people who were later fired doing stuff in the car of the hotel to have an egg roll, for no reason. So rehearsal, Julie walked in on stage, and he had a dull-breasted overcoat of his hat, attache case, he tipped his hat and said, Mr. Robbins, I’ve notified my lawyer. If little m is not. Restored to the show tonight. I’m pulling my whole score. Just sat again and said good night and left. So the little lamb went back.

Michael Kantor: Mama Rose. Who are your favorites?

Arthur Laurents: Well…

Michael Kantor: After.

Arthur Laurents: Oh, Merman was not my favorite. Her voice was my favorite, acting Tyne Daly. That was the best acting performance. And I directed that, and with Tyne, and with Jonathan Hadari, who played opposite her. You know, it was now. About 30 years after the fact. And what was the connection between Rose and Herbie? Sex. And we could play it. And humor. And they were both actors. So it was much richer and much tougher and much more vulgar.

Michael Kantor: And what about Angela Lansbury?

Arthur Laurents: Angie was, Angie is a consummate actress. She sang it really terribly well, which people don’t give her enough credit for. What she lacked was. She couldn’t be common. She just couldn’t, and rose is common.

Michael Kantor: Um, let’s just talk about.

Michael Kantor: Look at that enormous moment at the end of the show. In that place, you had to break some of the theater conventions, didn’t you, for musical theater?

Arthur Laurents: What are you talking about?

Michael Kantor: At the end of Gypsy, the very end, it’s not a standard sort of finale.

Arthur Laurents: But the very end of Gypsy really didn’t come off until I did it in London with Angela Lansbury. In the original, there were two things missing. One was in the strip. I always wanted super stage to roll forward over to the footlights and they’re bringing gypsy down. Well they said it couldn’t be done. So I thought well they all know more than I do. There was no bow because it was out, you know, after this woman was singing her guts out and suddenly to stop and say thank you ladies and gentlemen for a big hand and bowing ruined the whole mood. But Oscar said she needed, Ethel needed a bow because the way the thing is written, she’s never on stage to get a hand at the end of a number. So she took a bow and we didn’t like it, but. I guess it satisfied people in those days. But when I was doing again with Angela Lansbury, I don’t know what, how many years later, I suddenly saw a way to have a cake and eat it too. What happens is the whole number is in her head. And when she bows at the end, the audience applauds like mad, and she’s bowing, and the lights go out, and she keeps on bowing. And you realize there’s something askew here. This woman is out of her head. She thinks she’s really doing it. And it made it chilling. And then the end was even more, the end originally was kind of up.

Michael Kantor: So let’s just cover that thing we were just talking about, which was the show itself, while successful, didn’t make West Side Story what it is now.

Arthur Laurents: No, the music for West Side Story, when the show was on Broadway, meant nothing. Nobody did, they didn’t sing Tonight, they don’t sing I Feel Pretty, it was just nothing. As a matter of fact, it’s considered so little that the rights to the music were given to the authors by the producers. Then came the movie, which whether I liked it or not, that soundtrack album took off. It made a fortune. The producers came back, you know, and wanted some of their money back. But that is what I think took off and carried the picture. And still does. It’s that score. And then it’s worldwide. I’d love, I once heard it. I don’t go around seeing things I did. But I saw West Side in the. Comic opera house in Vienna in German sung gloriously that’s about all you could say for it but the music again sounded you know Tony was could gone to a fat farm but he sang beautifully

Michael Kantor: Let’s talk about a show you did a little while later with Harold Rohn. You cast a 20-year-old girl from Miranda.

Arthur Laurents: 19. 19 she was, Barbra Streisand. She came in. There was no part in the show for her. There was an uncast part of a 50-year-old spinster. And what she looked like then. Was a spinster incarnate. Her looks became chic a couple of years later. And she was, she had calculated spontaneity in a whole bag of tricks she did, like chewing gum and putting the gum under her chair. After her audition, I took a bet and I said to my assistant, go up, I’ll bet there’s no gum under the chair. There wasn’t. But when she opened her mouth to sing, I thought I was in heaven. I just kept her singing anything and everything. I was determined to have her in the show.

Michael Kantor: Do you think her story really sort of validates that Broadway myth of coming out, 19-year-old nobody, and…

Arthur Laurents: Oh absolutely. She knew she was going to be a star then. She hasn’t changed much. I think she’s less happy, and certainly richer. But she had it. Once she said to me, why can’t I play the leading ladies? Because I’m not attractive enough, isn’t it? And I said to her, you’re going to walk off the show. Be satisfied and shut up. But she was never satisfied.

Michael Kantor: Did you ever see Pins and Needles or talk to Harold Rome about that show?

Arthur Laurents: He sent me poison pen letters on wholesale.

Michael Kantor: What about David Merrick? He produced both of those shows.

Arthur Laurents: I love Barrick. He was a hoot. For all his money, everybody notices this, he had the worst toupee in the world. And he loved the color red. If something was red, it was good. He also, I made him laugh and he made me laugh. He told me a rather interesting thing so far as the theater is concerned. He produced under the rubric David Merrick or the David Merick Foundation. The foundation was for the risky projects. The batting average was higher in the foundation than in the commercial. And I wish some Broadway producers would really look that up.

Michael Kantor: But he was sort of one-of-a-kind when it came to producing the show, wasn’t he? What did he do on Gypsy?

Arthur Laurents: Well, on Gypsy, he went around saying Jerry Robbins is ruining your show and bad mouthing Jerry and what was going on every minute. And finally I said to, oh, and he also said to me, you know, Merman is not a box office star anymore. She’d had a flopper too. And if this doesn’t get good reviews, it’s going to close in three weeks. So at one point I said to him, if you feel that way, why don’t you sell out your share to Leland? So he said, OK, I will. But he didn’t sign the papers until the reviews came out. Of course, it’s different. I had my contract. Because of my experience with Jerry, that everyone had to have the same billing. I didn’t care where, what color, how big, how small. We all had to had the same. The day we were going to rehearsal, Merrick called me. He says, well, we’re not going to a rehearsal. Jerry wants his name in a box. Can’t have it. So finally Merritt called and they said, well, you lose. He has to have his name in the box. I said, how do you know I’ll give in? He said, because you’re practical. And he said, what’s it going to cost me? So I asked for quite a lot. He said it’s yours. And I thought, hmm, why is he so generous? Later I found out he had a contract with Leland Hayward. Leland had to deliver Jerry. He hadn’t. So what I asked for came out of Leland’s share. So with what Leland gave me and Jerry and Mermin, he had almost nothing. Merrick didn’t care.

Michael Kantor: You think Gypsy’s the greatest Broadway musical I’ve ever done?

Arthur Laurents: How could you ask that of me? It’s the one I like best. I’m most proud of my work and that of anything.

Michael Kantor: Why do you think people feel that way?

Arthur Laurents: I think because… It has a universality about it, in that it’s really about family. And as I said, about that need that everybody recognizes. It doesn’t depend on anything of the moment. Nothing is going to change. If the mothers aren’t going to push the daughter to go strip in burlesque, she’s going to go push a strip in some independent porno. I don’t know. But you know, that doesn’t, they’re pushing the daughters. They’re living their lives, parents, and it’s the same, it goes on, and everybody recognizes that.

Michael Kantor: Let’s jump to La Cage, 1983, the height of the Reagan era. What made you want to do La Cage at that time?

Arthur Laurents: Well, I didn’t want to do it. Fritz Holt, whom I was extremely fond of, and we had done Gypsy together, and he called me and asked me to direct La Cage. Well, it had been in the works to be produced by Alan Carr. Directed by Mike Nichols, choreography by Tommy June, a book by J. Preson Howen, a score by Maury Esten. And Fritz came on the scene and said, All those percentages, you’re not going to have it be impossible. Fire them all. So they did. And they got Jerry Herman to do the score, and Harvey Fierstein, who we’ve just done Torch Song Trilogy. So I thought that was good, and they asked me to direct. I said, yes, I never thought it would happen. I was doing it for a favor to Fritz. I hadn’t liked the movie particularly. And I wasn’t interested in a lot of camp. And then suddenly it was a go, and I had to do it. It hadn’t been written. And again, to my surprise, the writing was a wonderful experience. It was a terrific collaboration. And the trick of it was… I got an award from the Fund for Human Dignity, which is some gay organization, for that show. And they had bad-mouthed it, because it didn’t go far enough. And when I got the award, I guess nobody’s surprise spoke out, and told them what did they want. This was a show that in the beginning, when all these guys in drag came out on The men who’d been dragged to see it by their wives covered their faces. At the end of the show, they were standing up and cheering, two men dancing off into the sunset. I thought that was quite an accomplishment. It was the first time on the Broadway stage. Two men sang a love song to each other, and held hands, and one kissed the other’s hand. It doesn’t seem like anything today, but this was 1983. And also what the show was about, which was about again. It’s why it’s universal. It’s going to sound peculiar. It was about a boy having to accept a man as his mother. But it’s, again, about having to except your mother. And that people could relate to.

Michael Kantor: Continuing with La Cage, there were a lot of experimental, conceptual shows before that, you know, Bollies and Green Girls and Cabaret. The goal with this show wasn’t to break ground esthetically, was it?

Arthur Laurents: Ah, no. It was to break ground in gender. And as a matter of fact, a lot of the show, not a lot, but a good amount of it was invented during auditions for money. I would tell the story, and which we hadn’t written entirely, and I would try certain things out, and I’d say, oh, that went. For example, they had, we had… What we called the cajel, supposed to be 10 drag queens. And one day, I don’t know why, I said there are 12 and two of them are girls, but the audience won’t know until the end. Well, I could see from the reaction, that was a hell of an idea, that’s how that happened. It was, I would also during rehearsal test how far I could go. The relationship between the two men. It was very dicey in those days. And I remember the first time I staged, I had staged the song in the sand, it was called, between George Hearn and Gene Barry. And they were sitting at a table, and then one sang, the other one took his hand, and at the end, George leaned down and kissed the guy’s hand. And I saw the kids were crying. They were gay. And I thought, if I’ve reached them, that’s good enough for me. And there was a lot of trying to bring an extra dimension to it in that sense. That was the fun of doing it.

Michael Kantor: Why do you think it was such a big commercial?

Arthur Laurents: I have absolutely no idea. The first preview in, it was gorgeous to look at. Just spectacular. I mean, Theoni Aldridge did the most fabulous costumes in the world. And David Mitchell, the scenery, well some of the scenery was a fluke. Because when we were in tech in Boston, there was so much scenery I kept saying throw it out in the alley, throw it out in alley. And there was no style that held the whole thing together. And there was one scene backstage, and the set was so high, it looked like Folsom Prison. I was looking for those wardens running around on the upper level. So I said, just chop off the top. And you saw a sky. And I thought, okay, let’s have that unite the whole show. Oh, we see sky at the top of everything. And it gave it a style. But the first preview had to be canceled because the scenery didn’t. And we had very little advance, and they were running out of money. And the second one… I said, we can’t, it’s going to bomb because it’s not going to work. And the crew said, somehow we’ll make it work. And somehow they did. But the audience was a surprise. They began to scream. I mean, literally yelling. And at the end, they stood up even in the second balcony. Absolute surprise and a joy, of course. I hadn’t seen that since West Side Story.

Michael Kantor: What was it up against in terms of the Broadway, you know, the Tony Award that year, and how did it do?

Arthur Laurents: We won. We were up against Sunday in the park. But you see, I don’t believe in the Tonys. I mean, I think, you know, there’s a French expression, faux de mure. That’s the way you usually win, which means for wanting something better. I mean you get a year like this year. There are no original musicals. So something’s going to win and it’s going to be saying, oh, it’s the Tony winner. Well, it is the dog.

Michael Kantor: But up against that year, you’re up against the Sondheim show, right? Why do you think, why would people, any insight into why it won or no?

Arthur Laurents: They liked it better.

Michael Kantor: What’s this you were mentioning earlier?

Arthur Laurents: I think they also resented something else. The New York Times really went into a heavy campaign for Sunday in the Park, and I think people in the theater resented that.

Michael Kantor: This was before AIDS awareness.

Arthur Laurents: Yes, it was called grid then, I think. Nobody quite knew how, what an epidemic it was. What a plague.

Michael Kantor: What about your own inspiration growing up? I mean, I know you weren’t feeling like you were destined to work in musical theater, but was there a show or a particular person who attracted you to work this area?

Arthur Laurents: In musical theater. It’s just one thing that I feel to this day. Well, I would feel to the state if it could happen. I think the essence of theater is walking down the aisle when an overture is playing and the lights are on the curtain. The trouble is they don’t have curtains anymore. So you’re cheated. Life to me is surprise. And what’s behind that curtain should be a surprise. And that’s why the loss of the curtain is the loss of an enormous surprise.

Michael Kantor: Help me understand then, not in the negative now what we lost, but when you walked in and there was a curtain, how did you feel then?

Arthur Laurents: Well, you were leaving this world for another world. That was the whole thing. And it was, you didn’t know what was going to happen, but you knew it would be wonderful to music.

Michael Kantor: What do you think makes it so American? Didn’t start in Paris or London.

Arthur Laurents: Yes, it did. It started with operetta. And then it became musical comedy. What made it American… Was when it became musical drama. And I think because of the vitality and the gutsiness of America, that’s at its best in the American musical. The others, you know, the English did musical comedy before Andrew Lloyd Webber. They did all those dissy little things. You know, like Nono, Nanette, or whatever we called it. But a musical with balls began here.

Michael Kantor: What do you think the musicals that our country’s loved over the years say about us as a people?

Arthur Laurents: I have no idea what they say about it. Well… I think mostly, it’s hard to generalize about what the musicals say because most of the musicals are mindless, they really are, and I don’t think we are mind less. I think if they say anything, it is that we are very diverse and we will enjoy all kinds of things. Unfortunately, today we seem to be a nation of tourists. And I don’t mean only Japanese tourists. I mean tourists in the mindless sense that they only come to see something that it’s hard to get a ticket to. And then they say, well, we saw it. So that means they saw theater. And I think shows like that kill the theater, because the theater should excite. It should illuminate. It should make you want to come back, not to see the next hit, but to something that does something for you inside.

Michael Kantor: You think there’s a myth to Broadway? You think Broadway means to people?

Arthur Laurents: Broadway has a very practical meaning. The people who work in it, particularly writers. You travel around the world, and as much as I denigrate the Tony, you go to Buenos Aires or Mexico City or Tokyo, and they have on the marquee, Tony winner. What it means to have a show of any kind or a play on Broadway is that your work is going to be seen around the country and around the world. That is the enormous value of Broadway. It can’t be overestimated. Speaking for myself because I’ve gotten very involved in a crusade of trying to get new American plays I know that’s not your subject to Broadway they’re not there and So they’re, not seen and so they’re. Not seen around the country And it’s terrible

Michael Kantor: It’s sort of the pinnacle of, well, it’s the focal point, I guess.

Arthur Laurents: It is.

Michael Kantor: What do you think happened after Fiddler? Musical theater seemed to go in a different direction beginning in the mid-60s.

Arthur Laurents: I don’t know what happened to Fiddler, I mean, I don’t even know when Fiddlar was or what came after it. I just know the mindless musical came in with this wall-to-wall music. I remember Dreamgirls opened in Boston and it was a flop. And Michael said, Michael who I’ve gone off, yeah, Michael Bennett said, let’s sing everything. So they sang everything and it didn’t sound so bad. Because the book really isn’t very good and the dialog wasn’t, but they sang it. Well, if you sing it, it’s prettier. I don’t happen to be a fan of Dreamgirls.

Michael Kantor: That’s cut for one second. So you’ve been there for some of Broadway’s biggest successes. You’ve also experienced flops. Paint the scene. I mean, it’s a huge gamble, isn’t it? You show up, you don’t know if it’s going to run a week. Huge money is invested in it. Explain Broadway to someone who has no idea what’s at stake.

Arthur Laurents: And an opening night? Well, the old opening nights were exciting because all the critics came that night and it was live and die in one night. And a stage manager, the first play I wrote was called Home of the Brave and I was nervous. And he says, there’s no point in being nervous. And it has nothing to do with the show is good, the play is good. The actors are good. The moon has to be out. And that’s really true. A lot of it, the moon has to be at, which means timing. The mood. People invest in Broadway because it’s glamorous, it’s exciting, and it’s live, and anything can happen. That’s why you go to the theater. Anything can happen, in a movie it can’t and it doesn’t. I don’t know what else to say.

Michael Kantor: That’s great. Everyone says, the music was great, the scenery was spectacular, but the book was terrible. If there is a secret, how does the book function and what is the trick to making the book work?

Arthur Laurents: I don’t know what the trick is, but I know this. If the book gets the most blame and the least credit, and that’s why a lot of playwrights don’t want to write musicals, because you really have to give up your ego. And you know going in that’s gonna happen. If the show is praised, the book writer will get the least praise. If it’s the blame, it starts with him. I think anything in the theater, its primary function is to tell a story through character. And I think they have forgotten that. We don’t find character. And they start with a notion. And that’s why there are no second acts in plays or musicals. There’s somebody who says, oh, that’s a great idea. She is walking down the street, and she gets hit on the head by this guy’s cigar. And then what? Well, then what they don’t know. And they never find out. And so it dribbles away. And then we have what’s called the concept musical, which is beginning to slop over into the play. And I think that epitomizes the biggest problem with musicals because the purpose of the concept musical is to make it the directors, who nine times out of 10 is a frustrated writer, and he wants to show off and call all the attention. I think it’s also why we don’t have too many musical stars. They don’t want to stop. They don’t want the tension taken away from them. Goes back to what I say in Gypsy, the need for recognition. And at the end of Rosa’s turn, for me, for me, well, that’s the director. Not all, but most, particularly in musicals. What they forget is the director’s real purpose is first to tell the story and tell it through character, not through a lot of scenery and strobe lights and God knows what.

Michael Kantor: What about, going back to HUAC, what impact did that have on Broadway? None. Who were the Broadway guys that testified?

Arthur Laurents: The Broadway guys who testified, I don’t know all of them. Well, there was, names were named by Kazan, Jerry Robbins, A. Burroughs, Lee Cobb, Clifford Odetz. You could go down the line, but I also know there was a friend of mine named Stanley Prager, who was a wonderful comedian, and was rehearsing in pajama game, I think. And George Abbott, who was not a liberal, he said to Mr. Abbott as everybody called him, I have to go testify. Mr. Abbot said, well, get back to rehearsal as soon as you can. And Stanley did not name anybody. And Abbott didn’t give a damn. There was a man named Michael Gordon who directed my first play. He directed Pillow Talk in the movies that Rock Hudson, Doris Day. And he wouldn’t talk. He came back, Lindsay and Krauss, Howard Lindsay and Russell Krauss who wrote Life with Father and things like that. They were also producers. They were producing a play. They knew his political position. All they were concerned with, is he good? Yes, they are.

Michael Kantor: What about with Jerry Robbins? He did name names, didn’t he? He still worked. Why is that, why was it different on Broadway than in Hollywood?

Arthur Laurents: You mean, why was he allowed to work? Well, there was no blacklist in the theater. They didn’t care which way you went. There’s a famous story that people tell when he was directing Fiddler and Zero Mostel was in it. And Zero had been named and blacklisted. And they said, how do you feel about Jerry Robbins directing? And he said, well, I don’t have to have lunch with him. And I tell that story to someone who said, that’s a cop out. And it was, and I realized I was guilty. I had worked with Jerry on two shows, knowing he was an informer. I was blacklisted. Started to do a picture with Kazan when he was an informer. Wasn’t as black and white as I first thought it was.

Michael Kantor: What do you think is Steve’s best show?

Arthur Laurents: I think Steve Sondheim’s best show is Sweeney Todd. I think part of the reason is he found something in the character of Sweeney that he identified with and the show is enormously emotional because of that. And import out. An emotionality that I don’t think was in his music until then. Well, some of it was. There’s some in the show we did called Anyone Can Whistle. But I think Sweeney is his best show.

Michael Kantor: What about the fact that people say that Sondheim is steering the musical theater away from optimistic, abundant happiness into these dark areas and that’s not good.

Arthur Laurents: I think the complaints about where Steve has steered the musical should be complaints against the copycats. Let him do what he want. There’s a dearth of originality and it’s one thing to influence and it is another to copy and these people who try to copy are just inferior.

Michael Kantor: What do you think his greatest gift to the musical theater has been?

Arthur Laurents: I think he’s the most brilliant lyricist that we’ve ever had.

Michael Kantor: Can I ask you to talk about what when people say he’s a brilliant lyricist, but his music is that?

Arthur Laurents: Steve and I are extremely close. Which means… I’m not going to say a lot of things.

Michael Kantor: Things concerning the current theater. One is revivals, and one is Disney and huge corporations that don’t really respect the writer in the way that Broadway producers used to. How do you feel about the current state?

Arthur Laurents: What was the first one? Revivals. The problem with revivals for me is, and I had this with Jerry for a long time, I don’t think you should revive a musical any more than you revive a play. You do a new production, a new look at it. Sometimes it can go get absurd. But, why do… A replica. As for Disney… I don’t happen to be an admirer of these. I think Beauty and the Beast isn’t bad. I thought Lion King was a mess, frankly. I mean, after the first five minutes, I was bored. They’re getting people to come to the theater. And at least that’s something. The treatment of authors, well, it’s movie moguls. They have no respect for anything or anyone. They use you and they chew you up and throw you out. I think that’s why Garth Drabinsky, who behaved like a movie mogul. And I don’t believe you can produce a really good show by committee. And they haven’t.

Michael Kantor: Since you started with West Side, what would you say, apart from the economics, which is clear, what’s the biggest change? Is that it?

Arthur Laurents: The biggest change in the theater that there is almost no producers. There are people who put up money. They have no faith in their own judgment. They really import things from England. Or they… Back somebody they consider has a track record. They don’t really know, and they’re not willing to take a risk. It’s hard for me to talk about the music. You know, I know nothing technically about music, and both Lenny and Steve and Julie trusted my ear totally. I don’t know, a diminished fifth from a sharp. I think there’s something about Lenny’s music that the minute you hear it, you’re excited. The blood goes faster, the pulse beats faster, and you feel alive. You know, in that moment in that what is, what has become the overture of West Side Story, but never, no overture was ever written. It was just dummied up and kept. When they go into the mambo, the whole audience, you know, you can feel they want to scream with excitement. It gets to the gut. It’s true.