Speaker OK, um.

Speaker Sorry, you know, I totally forgot the question, but we’re going to start with his ideas of beauty and how, you know, he was sort of inventing I don’t know how he’s putting his finger understanding popular tastes in popular appetites.

Speaker OK, well, I think Paul’s intention when he first started writing is reflected quite simply in the letter that he wrote to John O’Neill when he was 20 and identifying John Neil’s appreciation of natural beauty as something that was true to his heart and finding clearly as he was in the marketplace that his poetry was not going to allow him just to get on with life. And not that he did that well anyway, but financially. But I think that that was when he turned to writing, not as a reflection of his aesthetic sensibility, which, as I argue in well say that, you know, it wasn’t a reflection of his true sensibility, but rather his ability to be attentive to the cultural desires of the reading public in the 1930s and 40s, which were very sensationalist, as David Reynolds portrays in Beneath the American Renaissance. So he was able to adapt those cultural desires for spiritualism. However, sexuality, all of the predominant penny pamphlet interests of the public, despite the fact that his true desire was to be a poet and to reflect his sense of beauty. So that was his initial desire, which was frustrated by the marketplace.

Speaker Yeah, that’s nice of time. Let me ask it again, Buzby.

Speaker So when when pose at the Southern Literary Messenger and he has a famous debate with his boss, Thomas Wade, about the story barrenness, for example, what tension is he discovering between the demands of the marketplace and his own aspirations and ambitions at the time when he was pushed to write the kind of horror story of Veronese that he later regrets allowed him, I think, to deal with an issue that he had to deal with his whole life, which was the conflict between his desire to be a poet and to reflect a natural beauty as compared to the desire of the reading public at the time for sensationalist literature to the to the extent that he went and Veronese, he never went again.

Speaker But he certainly was able to then understand the way to modulate both the desire of the public in his own undercurrent complexity that makes his work different than what was then popular. So Poe never let go of his intellectual demand for movement outside of the practical and moves towards what he often says is soprano beauty or soprano mysticism that kept him writing even though he knew that that was.

Speaker That’s it. Forget it. OK, cut and paste that at the end of the story. And that’s good. Um.

Speaker Talk about freedom from very early on, how Paul was was incorporating visual imagery or expressing some somehow drawing on the visual world in ways that other writers really didn’t do. If that’s if that’s indeed what you think or what are you not doing in a way that was different? How did he and without getting too arcane, because, you know, we are in an eighth grade audience.

Speaker So you’re talking to a bunch of eighth graders, right? What what made him different with visual material?

Speaker I think we want to see Paul in a way that reflects the kind of attraction to the deviant, to the psychologically profound. And we forget that much of the idea of aesthetics that he uses in his writing reflects a desire for a kind of harmony that he saw in the visual works that surrounded him growing up in Richmond, the many homes that he was in, that he saw paintings that stayed with him. Then when he moved from that area to Philadelphia and mostly the longest time he stayed anywhere was Philadelphia for six years. And his acquaintance with the Sullies both in Richmond when he was young with Thomas Kelly’s cousin. I think it’s a cousin. You’ll have to cut that as well. But quite frankly, the the time in which he spent the most energy in Philadelphia was seeing works at the Philadelphia Academy of the Fine Arts and having friendships with artists at the time.

Speaker He then moved to New York, which was at the height of its becoming the center of the arts. The National Academy of Design had been there for a while, but the newly formed American Arts Union and the first gallery of the New York society, I think.

Speaker Well, anyway, let’s go back. I would like to move to don’t don’t go to die in one place.

Speaker OK, so what happened in Philadelphia? What did he see? If you can give an example of a painting or an artist and how he incorporated that and took it on board.

Speaker OK, when he was in Philadelphia, many of the shows at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts were exhibitions of European paintings so that his. Curiously, as much as he was surrounded by American artists when. You see, I can’t say that either, because that’s not true. Let me try again.

Speaker You know, all we’re looking for is very general. I know, but it’s not just one specific case. Yes, yes. Yes. And my brain is, as I told you, my said if I had my book, I could open it and show you what.

Speaker But I did read parts of it. OK, so I read every every part.

Speaker But in the part about Philadelphia, there is an important artist, visual artist who I cannot remember that he does talk about a number of times in his work who was from the 17th century, but be damned if I can figure it out now.

Speaker Well, it would really be, too a little too narrow for us anyway, I guess.

Speaker OK, I guess maybe just something about how how Poe was very attuned to and then familiar with artists of his time.

Speaker He would go, do we know he would go to museums and made its way into his work?

Speaker Right. Well, that’s that’s what I’m arguing for in Philadelphia. I think the most potent way of talking about that would be his time in New York City. So, OK, that would be more relevant because when he worked at the Broadway Journal, he worked with Charles Briggs and Charles Briggs and as the first owner of the Broadway Journal, his. Most of his writing was art criticism, which actually in my research, I’ve discovered very few newspaper articles or magazines or whatever really did art criticism while Briggs did, and the two of them had very similar sensibilities. They were both harsh critics were harshness was needed, were unafraid to insult even the most important artists of the time, like Thomas Cole or Frederick Church. And Poe was a close, obviously companion to Briggs, despite the fact that their relationship ended in not such a great way, which is fairly typical of Poe, because he ended up alienating him from his drinking. But nonetheless, when they were working together, Briggs was on the board of the.

Speaker I see that my brain is just not. No, no. He was on the board of the American Academy of Design. No, that’s not right. Americans are.

Speaker Forget it. See, I told you, my brain is a bit old, but the point was that when he worked with Briggs, he came in more contact with visual artists in the Henry Hudson Valley School. So that.

Speaker That impacted my argument that he moved from the sublime in his early days, which is suggesting a sense of fear and horror before you in a humbling of the of the person to the grandeur of nature, to a more sense, a sensibility that was closer to his youthful appreciation for beauty, which impacts a kind of sense of harmony in that he saw in the paintings by Thomas Cole and Frederick Church. And the domestic peacefulness that was pictured impacted his last story, which is the lender’s cottage. And even in Lander’s cottage, you see the movement from the narrator’s being up in the mountains. Moving down to the domestic scene of Lander’s cottage itself, reflect a kind of desire and post part to move away from shock and horror and violent perceptions to a more domestic, peaceful, harmonious, beautiful scenario. And he was he had written that he would again write a third story to fit in to this what would then become a trilogy from the domain of Arnheim to lenders cottage to whatever it was that he was going to write, which he never got a chance to do since he died. Now, I think what’s important about Lander’s cottage is that it is something he wrote. Before he died, that is, he’s finally giving up on some level the desire to meet the demands of the marketplace and right. Truly what he loved as reflected in his youthful desire to write about beauty. So I just wish he had lived longer. And we might then have a different sense of who Paul is, not just the person with the ability to, you know, plumb the depths of human depravity and and horror and fear. But someone who who as an artist, as a person who strove to feel what it means to have a glimpse at the personal beauty and how writing could in fact be some method of sharing that potential with others. So I think that. We lost him too soon, and it’s unfortunate in that regard.

Speaker Ironically, most of the painters he mentions in his work are European, but there are ways in which those European artists who are the teachers of the American artists. So it’s sort of a subtle way of denying, as he did in his early writing, placing his pieces in the United States and America. It’s a kind of suggestion that we are still a youthful country and we need to defer to the artists of the past.

Speaker So he he you know, people see him often as very arrogant and abrasive and critical and often demeaning of his audience. But actually, I think there was a humble side of people that deferred to the past, like Shali and all of the great artists from the past. So, OK, that’s OK.

Speaker The rest of the stuff, I don’t know. Just one more thing. One more thing. When you come to the end of just stop for a moment. Don’t don’t say OK. Oh, that means we can’t we can’t edit at the end.

Speaker OK, pause for a moment. That’s OK. I mean we can but it makes it harder. Um the uh the the, the Garaty I suppose.

Speaker I guess there for that we know of Michael D is the expert on that.

Speaker I don’t know if there are four or not mentioned in the other night. Yes. Welcome people. You mentioned the one that’s on the cover. Yes. The daily declarative. Yeah. Can you talk about this one? And you said something about the only one where we see his hand. Correct.

Speaker Could you just talk about that? And I don’t know if you want to look at it one more time, but. But not you can’t look at it while you’re talking. So, OK, just remind yourself.

Speaker But I want to ask you, OK, um, the daily type of one on one of the familiar ones, what is it we see? What kind of man do we see? What do you take from that portrait?

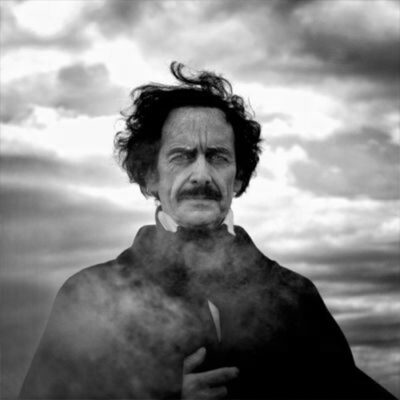

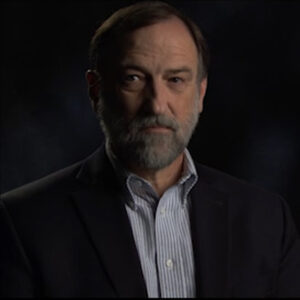

Speaker The daily daguerreotype, which was taken during the time when he lived in New York City, pictures him in almost a contradiction between his workman’s hands. If you look at his hands, the knuckles are are larger than I would have anticipated and conflicting with those sort of almost female face that you see a delicate face, that curled hair, the the delicate nose, and then you see these these hands who were and it reflects, I think in many respects, the hard working nature that Paul was a hard worker. You know, people like to say that he drank all the time and he was, you know, dysfunctional. But if you look at the for forty years that he lived and the amount of work that he produced and the tireless efforts that people describe him at his jobs as editor, he he he’s a workman as well as a a delicate human being. So I think that was what was very attractive about this particular digger type. And because it’s only about four or five years until his death, you see that he maintained the desire to be an athlete of the class that he was raised and despite the hard work that he had to suffer because of John Allen’s disinheritance. So I think this is a particularly poignant daguerreotype, which gives us both sides of.

Speaker Paul, great. Thank you. The ultimate tool or ultimate will.

Speaker I never know how to pronounce it either. OK, well, you know, I won’t be able to say it. That’s fine. Don’t don’t even say it.

Speaker But what what do you see when you look at that?

Speaker I think a profound sadness that in that one. But it’s hard to think about the guera types as being what we imagined to be photographs on one hand because of the need to say so still. And, you know, for the length of time you had to stay so still and for the time in which the imagination, which I’m sure was swirling in his mind at the time that he’s being shot, as it were, reflects the current situation in his life. So I think there’s a great deal of sadness in that.

Speaker And why was the current situation so OK here? I think it was right after he had tried to commit suicide. What year was that? It was eighteen. Forty. You know, you can have what he had. He had just he was just he had just this is because of Lord.

Speaker That is before obviously Virginia died. Yes, was taken so I think comparing even the mustache you see are kind of giving in a giving up.

Speaker OK, so can I ask you about that one? OK, all right. And this was not the last one. I think it was the second the last one to go over that again because it was paper revealed through. Yeah, I didn’t know you were. That was the last three times you take it back. Yeah, I know. That’s what we have. I think he’s struggling there, too. OK, well, let’s talk about this one. OK. OK, so called automatable.

Speaker But, you know, I don’t want to take you on a day or two after he tried to commit suicide.

Speaker So if you want to refer to that, OK, the ultimate thrill daguerreotype taken a few days after his attempted suicide reflects the kind of despair and disillusionment and giving in to a kind of. Hopelessness that the death of Virginia, his unsuccessful suits his own. I mean, he wrote. Lenders’ cottage there at the same time. To creating a kind of ideal domestic space that in this together type suggests that he will never find that he will never grasp, just like in the Raven, his lost Hlynur, he will never grasp a time of repose, which is a aesthetic sense, a sense that Poe felt was most important to have a sense of repose, which clearly in this daguerreotype, he despairs of ever finding beneath the portraits of him as a young man, which some of the there’s a painting that, you know, they’re a bit kind of they’re kind of dubious.

Speaker And yes, I would say so. All right. Do you have anything you want to say?

Speaker I mean, could you say something about the fact that, you know, after he died and became famous, people wanted to have some sense of what he like? Maybe you could just even talk about the fact that there were these sort of idealized images of him.

Speaker I wouldn’t feel comfortable with that. I wouldn’t know about it.

Speaker Can you talk about him, his interaction with women writers and women poets as a reviewer, as a critic, as a competitor, as a.

Speaker Yeah, as a competitor, I would say. Well, this is an unorthodox reading, but.

Speaker Wijaya, which he called his favorite short story. He says to women in most. Inhuman kind of position, they’re both objectified the first lady as this intellectual pair, you know. He poses the idea as this intellectual acme of perfection, which, of course. Is unreachable, and then when she dies, however, a way that she dies, he replaces us with a another objectified woman in the blond, blue eyed fair Weena. And in the end, despite the supposed reincarnation of Lydia, which I argue is totally. Pose sleight of hand, because the narrator at that point is supposedly opium obsessed, etc., but the end result is that he’s telling the story after all of this occurs and he is alone.

Speaker And I think that these deaths are his desire to get rid of people like.

Speaker You see my brain, my dad here, who is the woman, you know, who tells Elizabeth someone else?

Speaker No, no, a writer family. I was going to know the the right Margaret Fuller. Yes. OK, so I’ll try to pick up from there.

Speaker That his he is reflecting in this story his.

Speaker Had a total.

Speaker Is reflecting in this story his potential jealousy, but more so his. Frustration with people like Margaret Fuller, who’s writing.

Speaker Reflects a kind of desire for the female to replace the male, I think is the picture of Margaret Fuller in the Broadway Journal reflects that kind of disregard and dismay that he felt with women writers. And also, if you look at the two stories that Poe wrote with female narrators, and there are really only two, I mean, you could say that the voice and Eureka, the letter writer might be female, but there’s no real sense the two stories that perhaps female narrators predicament and the second and second tale of Sheherazade, both women end up with their heads cut off. So the storyteller in the predicament and the story that. Paradigmatic storyteller of Sheherazade both end up dead with their heads cut off. Completely so I think he had very you know, as much as we would like to make postfeminist if we do, I don’t know. I think he really wished women would keep quiet, especially people like Margaret Fuller. And in the stories, those very explicit stories of the female narrator, it’s very clear he cut off their heads in Lygia. He gets rid of the both of them die. And yet he’s still alive. And he he really that it was kind of a disingenuous love of Ligeia. It was, in my mind, a competitive sense that she was teaching him. She couldn’t figure it out, but he somehow lives behind this.

Speaker Anyway, that’s it, that’s interesting. That is different from certainly what some other people have said, of course, but what about that circle of women? You know, the oh, the poet Fanny Osgood’s, you know, that that literary salon world that he was in and he deferred to them, you know? Sorry, I was still talking. Sorry. Start again.

Speaker He deferred often to female poets and praised their work. But some of it, I think, had to do with his desire to get published and the connections that these women had with the means of production.

Speaker And Margaret Fuller was not one of those women, she was her work was clearly feminist and clearly rallying for female voice. It wasn’t sentimental and. In a kind of. Genre that women were supposed to write in, so I think that despite what other people might say, I think based on his work, his actual writing, he really did not appreciate the. Effort to enter that kind of male intellectual world.

Speaker It’s good, good, good.

Speaker Why is his likeness so iconic and how does that feed into his enduring popularity?

Speaker Now, why is it he’s on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and even The Simpsons and he’s on T-shirts and coffee mugs?

Speaker Well, I think that his image is all over the place in popular culture because it reflects. Are in admiration.

Speaker I think pose image is everywhere in American popular culture because it symbolizes the kind of attraction people have to his horror stories, to the sadness, to the psychological depth that he was able to express for them and for us now. And he is, I would say, undoubtedly the most popular American author from the 19th century without fail. And I think that the.

Speaker His popular image.

Speaker Is a reflection of the way that his work opens itself to so many interpretations, especially the fact that it’s so full of visual imagery itself and the graphic quality of his writing has allowed for artists, both visual artists, musical artists, you know, to take his work and do what they wish. So as a kind of visual image, the visage of Poe symbolizes the potential for interpretation and the empowerment of the reader to make those interpretations. And therefore, it’s seductive. You know, it’s powerful in that regard. Clearly, popular culture goes over the edge with the television program about the professor who teaches poetry, has all these students murdered and et cetera, et cetera. But I think that nonetheless, he stays in our sensibility and the image is a reflection of that.

Speaker No, that was good. OK. All right, I love that. Is there anything you want to add? Yes, we do.

Speaker I think I think the most important thing that I would like to hope that would still appear in the film would be the fact of his love of beauty and his movement towards the domestic. I think that’s something people don’t think about.

Speaker They only think about parts of the world. Let me ask you this.

Speaker What is what is the thing that that people don’t know about how that you wish they did know?

Speaker Pose artist extensibility and his intellectual acumen, his valuing visual sensibility and beauty and pose is counterintuitive to the popular image of Poe as this person who embraces the sublime, who embraces all of this horror and fear of the soul and all of the black images that we associate, dark images that we associate with Poe’s sensibility. From youthen. He wanted to be a poet. He wanted to have peace. He loved such a troubled, economically problematic life that, quite frankly, by the time he was 38, he wanted some respite, he wanted some repose, and he wrote that idealized. Lambdas cottage as a kind of plea in one of the memories of one of the people who. Was able to be at some of the talks that he were informal near his Fortum cottage out in nature. One of the people who remember him remember him pointing out, look, look in the tree. You’ll see how the light reflects and creates imagery. That sensibility is that of someone who is constantly seeing around him, taking those moments, those visual moments and holding them as moments of beauty. And we certainly don’t associate that with peril. But that was this young woman’s memory of him that he which he was he was teaching her to see to take whatever place that a person is in and find some visual harmony or beauty in it. Thank you.