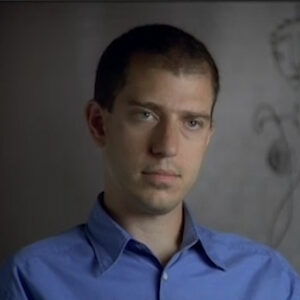

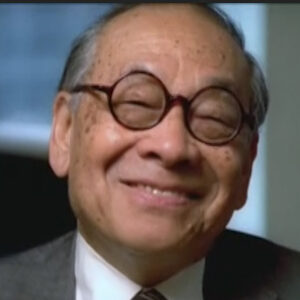

Brendan Gill: I think I was very late coming to Calder and seeing what he was up to as an artist. First of all you had to see the work and then you had to wonder what he was up to. And it was partly because of my interest in architecture. And so August was fairly late in his career as well. I wasn’t conscious of him and the degree to which his playfulness and everything, he represented something really quite fresh in the world. Unknown hitherto and very unlike the soul, recited sculptural work that I was more familiar with. And it was through the architectural need was very great at that time when so-called modernism and architecture came along. That Calder was absolutely indispensable to the kind of buildings that were being built at that time in the post-war period because they were so severe and they were at the very worst, let’s say, slab like and they were in desperate want of some humane touch that would say, yes, this was actually designed by a human being and deserves to be singled to among the fellow human beings who are going to occupy the building. Otherwise, what on earth were they? It was the quality of the penitentiary at best. Alexander Calder, above any sculptor was able to diminish the sense of the penitentiary in the architecture of the post-war world, and it transformed buildings and transformed open spaces. And in the worst years of what we call in those days a nasty thing called urban renewal, people would knock down old buildings and create in ancient cities like New Haven and Hartford, open spaces which would like death. And what would you do? Wonderfully. And the only thing you could do would be to put an Alexander Calder in that empty space. And then it wasn’t an empty space anymore and it wasn’t dead anymore. It had come to life. And so this was when I saw my garden with the engrossed terms, the utility of the sculptor, what he is able to do. And of course, it wasn’t all that unlike given thought to what his parents and predecessors, sculptors in the family had been doing even back as far as the Civil War. The whole notion that in those days when you held an open space, he didn’t know what else to do with it, especially in Washington. You’d put a heroic figure there. You’d have a bronze. And ideally, you’d have a bronze on horseback. You’d have Alexander Alexander Jackson doffing his cap in the air across the White House. So Calder became a public figure to me in you know, in crazy architectural terms. And then the more I knew about him, the more interesting it became in terms of sculpture and how sculpture was altering upon my very eyes thanks to him.

Interviewer: Are there any pieces that strike you? Flamingo with the plaza in Chicago?

Brendan Gill: Yes, in my hometown of Hartford, Connecticut, which is really what I was talking about the catastrophe of urban renewal there where they had knocked down buildings just on Main Street in Hartford and spoiled everything. There is now great big bright Alexander Calder, and he adequately fills the space. It is a big color palette expands to fill the space. And of course, that was one of the tricks with Calder. And he was very clever about and knew about was the degree to which scale meant everything. This is a very nice, comparatively small Calder at Lincoln Center in New York City, which takes care of the most awkward gap in the world. And then in the quiet, in many respects, quite miserable design of Lincoln Center, where the sidewall of the Metropolitan Opera. And then there’s the Vivian Beaumont Theater. And then there’s a nasty little gap, which is really where you went to the library, the performing arts at Lincoln Center. And it just doesn’t work. And so there’s a nice little black Calder. Just the right size. And it makes you feel good as you go by. But besides it bad wall of the blank wall of the Metropolitan Opera and the art wall and Vivian Beaumont, which isn’t related to it all. And you pass the Calderr. You feel better already. And in fact, you prefer looking at the Calder which is there to the Henry Moore, which is kind of a green glop in the middle of the reflecting pool to the right as you go toward the library. So he was able to do playing with scale. He was able to rescue the building. I don’t know whether he himself was conscious of the degree to which he was being used as a one man rescue operation. But that’s what it frequently was and to make people feel joyous in the presence of some of the buildings that were built in his time. He made use of it with purpose is a remarkable thing to look back on.

Interviewer: So size wasn’t about enormity of scale. It wasn’t bigger is better.

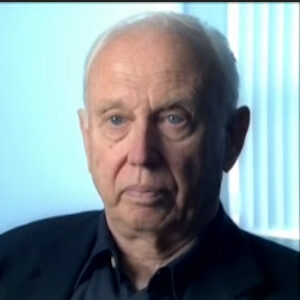

Brendan Gill: Oh, never that. And of course, what was so interesting about Calder was that he was a master of scale from the beginning. Although I didn’t know about it at the time, as I said Calderl was the man who began with these tiny, playful things, the famous circus 1927 or whatever it was when he was he was fooling around with this with bits of wire in Paris, as if to say two things. One, I’m having a very good time until I’m not a bit like my father the sculptor who is doing heroic work is at these immense and to some extent quite pompous, although very skillful Old-Fashioned Turn of the Century or Edwardian sculptors sculptures. So Sandy Calderr was able to go from the playful wires to these enormous things. I don’t know what the biggest one was. Twenty seven feet, whatever it was. I mean, the stabile that the big floating mobiles could get bigger and bigger and they could be like pterodactyls. And the resemblance to pterodactyls and indeed even the stabiles are often animal forms that we have, I think in our unconscious, that kind of a union unconscious. And we look sometimes at a Calder waiting there for us. And at first we have to decide, is it friend or foe? And then it turns out because of the nature of Calder himself, who is sweet, dear bear of a man and hugging and kissing. It was friend and not and not foe. But there was something in there, something primordial, something there are perhaps our DNA three hundred thousand or three million year old DNA which responds responding to those shapes. And what’s really many, of course, were the things that seemed to flow so, so delicately in this guy because they defy gravity and again, are heavy and intellectually obtuse structures that we lived in in America in the last 30 or 40 years. These structures needed the defiance of gravity to make them even possible to want to enter. Well, wouldn’t want to enter a slab if it will be like death to do so. Might as well enter the pyramids and lie there mummified. Not at all. Not, with Calder.

Interviewer: Let’s cut for one second. How did that strike you to learn such a phenomenon.

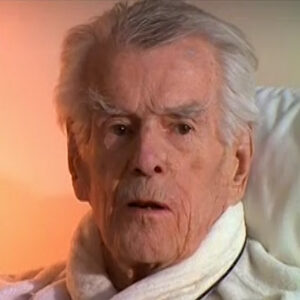

Brendan Gill: It was an amzaing thing for everybody to realize that sculpture, which up until Sandy Calder’s time was the very it was an expression of solidity, emotionalessness. Indeed, the greater sculpture in Greek or Roman terms. What was the greater degree of its stability of its of its unmoving ness? And that’s what we were apparently in pursuit of. Not at all. It turns out that something else was possible. The flight of a bird was possible or the seeming flight of a bird or the capture of the flight of the bird. And when Leonardo da Vinci and his drawings of birds in flight list, well, they look not unlike a Calder mobile. That, too, is in flight or and you don’t know whether it’s coming or going. But it hangs there and delights the eye. And it says we are ourselves then more than earthbound. If that can be free of gravity as it seems to be, then we can be free of gravity. So we want to identify with that. With that quality of bird likeness Calder invented. All, by himself. A perfectly wonderful thing to have done. And then nobody, I think, would have guessed the man who could do this flying object is Bird like thing, I think was also the man who could create these prehistoric beasts on the ground, that it were so seemingly sternly there and then turned out to be friendly and portable and compatible. And and that that we wanted to walk around and be inside. People always grew up. You watch people. They always go up to a Calder stabile and put a hand through order. They put their heads who are to make faces or want to be pictured snapshots, you know, of people doing that. I find that irresistible myself, which is to say that I’m in effect, in a crude way, slightly could be said to be bonding with this work of Calder.

Interviewer: Yes. Yes. No. OK.

Brendan Gill: The way he was able to criss cross the whole boundaries of art. He was always playful. He was and he was it was designed to sound of great arms to me always that they could be at play in so many different forms. It’s not surprising that they do this. It’s not surprising that Leonardo da Vinci was making war machines for de Medici. Why wouldn’t he? That’s all fun, too. And Calder would is exactly that way. And being able to be the stage work and be able to do, oh, a dozen different things. Anybody it anything would be likely to get something in response because it was a challenge to him, to the ingenuity which was in his hands always his hands and then it was mind and it burst in the hand I think. And small things, big things were different.

Brendan Gill: I believe that the first time I ever met Alexander Calder was that Robert Osborne’s House up in Solsbury. Well, Robert Osborne, one of the most adorable if there isn’t too strong willed men that I ever met in my life filled with charged with life in something like the same way that Calder was. They were made for each other in that respect. They were both joyous human beings. And if anything could be said about being true to me, I seem to want to collect joy as human beings. And there weren’t that many joyous people in the arts. Contrary to what you would think, it’s also true there aren’t many dentists, as far as I know, or particularly joyous truck drivers. But I like it when I find joy as people in the arts. And Robert Osborne was a remarkable caricaturist, an artist, and as well as able to be intellectually curious up to the day died. Whatever it was, 88 ninety, whatever it was. In fact, he was writing me Osborne at least a year, you know, saying we are now clearly ality his wife and he we are now clearly on the downward slope, on the downward slope at 88 is not bad. Also to recognize that you’re on the downward slope at 88 is not bad. In any event, they had wonderful parties, up in their great White House, little White House, pretty White House and Saulsberry, Connecticut. And it was a party there one evening that Sandy and I met. And he loved to drink as I do and always have and always will. And and he was again, he was a happy person drinking. He wasn’t he never became morose in his cups or he never became a belligerent. An awful lot of writers, it seems he may become extremely pugilistic when they drink. And others that I’ve known in my lifetime burst into tears and irreconcilable to life in ways I’m not interested in. But anyway, he was merry and I, if I may say so, was merry and Elodie and Bob were showing some film because she was very handsome and worked in film with the Museum of Modern Art and and he would read a book both after dinner when we were there in the dark, supposedly watching these movies that that the Osmonds had brought up for us to see. Both fell fast asleep, which it was just another bond that I think was characteristic of both of us that occasion. And I felt lucky that I saw the last glimpse of him that I ever had was out there at the Whitney at the great party, the great celebration, the great show. And and ever again, he was he was merrily in his cups and enjoyed but whatever age he was. And seventy seven, seventy eight. Just about to die. What could be more wonderful than you see with the reclaim arm of the world at this particular moment and then wave goodbye. And in fact, you know, a quick goodbye and laughing turn away as Yates says. And that’s what that’s what in effect Calder did. He waved goodbye and laughing turned away. And I was very impressed with that. That’s that’s what what Shaw calls him when it was quite a splendid death or splendid death. And he was so happy on that particular evening. But I didn’t I didn’t know him at all. He was an acquaintance of mine. And I knew him only through his really largely through his work and then through a kind of an imaginative construction of a friendship that didn’t exist. And people my age have to resist the temptation to pretend to have known people better than they did simply because they’re among the handful of people left alive who knew them at all. So I, I pretty I make an effort to keep my distance and say, in reality we were acquaintances, not friends.

Interviewer: So you’ve never had any heart to heart conversaitons?

Brendan Gill: Oh, no, no, no. Nothing like that was a sort of jollity with badinage. And and I would I would be, in fact, if anything, listening to Osburn in him rather than than any other particular way around.

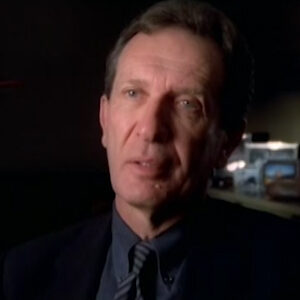

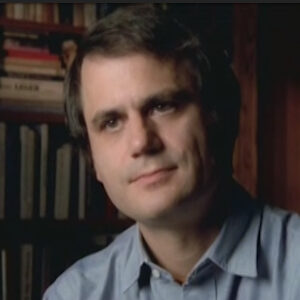

Interviewer: Let’s let’s talk about time. Essentially, he went to Paris first in 1926 Can you tell me what was happening here and over there that might have drawn him there as young man. He would be twenty eight years old.

Brendan Gill: Well first of. What was happening here was that everybody was leaving here to go there. It was the place to be in the 1920s. And in fact, that’s a little even a little bit late. But that’s when, you know, Hemingway’s of the whole post-war. The so-called Hemingway lost generation had moved to Paris in part because it was so cheap, in part because it was such a desirable place for an artist or a writer or a composer to be. Virgil Thompson was there. Scott Fitzgerald, was there. Ever anybody who was engaged in the arts very likely to turn up in Paris and to live quite well and have a good time and and to and to join other people in the same milieu, which is sympathetic to what they were doing. They were breaking new ground or trying to do so. And certainly Sandy was breaking new ground more than anybody as it as it subsequently turned out. And why wouldn’t you be there if you were 28 years of age, you know? And it was a choice between Paris and New York or Potaq Connecticut. And it wasn’t surprising to find there would have been surprising, would be not to have found him there. And then, of course, as history books tell us, he was greatly influenced by the artists that he became friends with in the area, Miro and others, that he was able to move into this new dimension of things. If he if he was doing mobiles Miro, Miro’s line in painting and dots and all that, those are those are mobiles on canvas. And they’re, to my mind, very closely related. And again, a wonderful thing, a shared view of what was a possibility. And in order to make it something they were makers and to be in Paris, I suppose, to be a maker. It was true of all the writers who were also there. They didn’t go there just to meet Joyce. They went there to meet each other.

Interviewer: Move into the 30s. He actually has already started doing his Calder circuses in the late 20s. But in the thirties he does sets in the late 30s, he does his first large scale stabile in the late 30s. What’s happening? Has has has art, the world of art changed in the 30s. First of all. And what’s going on?

Brendan Gill: I dont think I can answer that. That’s too hard.

Interviewer: 40S, what’s happening in the world of the 40s, the war.

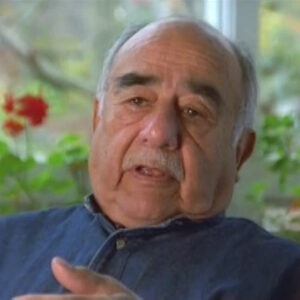

Brendan Gill: The great interrupting factor, of course. Well, first it was the post-war world, Paris and the breaking of boundaries and the breaking of barriers, all that kind of thing. And then there was the Great Depression, which cost that caught everybody by surprise. Are you not totally surprised? And the people came back from Europe because, among other things, their parents were no longer able to support them. They weren’t really and many of them earning any particular living at that time. And so there was a kind of an abandonment of the of the Paris position, as Malcolm Cowley wrote about, you know, the exiles return. And he was part of that whole thing. But their whole view of what was possible to be able to be done was altered by the disaster of the depression, which was followed very shortly after by the disaster of the Second World War. So that I speak of this period of interruption, which was in many ways catastrophic for the arts. An awful lot of stuff simply disappeared for a long period of time. You don’t ordinarily get catastrophes of this kind on this scale and be almost like the bubonic plague sweeping through Europe or in our time just in the last few years. What happened with AIDS, with with just a whole generation of people going almost to a slaughter world?

Interviewer: Did it change the world of art?

Brendan Gill: And I think everybody felt this very much a horror emerged, but both out of the depression when everybody was sort of on the dole and doing work to keep themselves alive on the WPA and then breaking through after the Second World War would seem like the dawn of a new period where something wonderful might then be able to take place. And that was when I think people like is Calder became popular figures. And that was the period when artists for the first time began to be written up and be photographed in Life magazine and have it. And they had their moment of glory or their years of glory. And by that time, we invented the whole post-war world of hype in which everything was blown sky high. And it was everybody was able to be famous, as Andy Warhol said, for his 15 minutes. And Calder survived all that. He was obviously the biggest artists are not troubled by the corruptions of fame or we hope they’re not going to be. I’m not sure about Picasso, but but call it was never that famous as to be disturbed or distressed or even even to have his life injured personally or used up or usurped by fame. Very dangerous business fame, evidently.

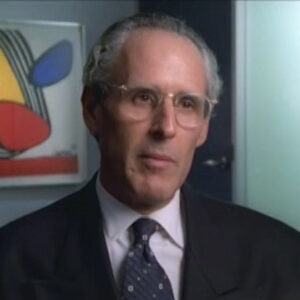

Interviewer: Let me let me go on something similar to that. You talk about this wonderful human being, this wonderful, childlike sensibility. Does that have any bearing on the seriousness of his art? Is it the less serious?

Brendan Gill: There is no there’s no connection between the what we think of as the seriousness of art and the playfulness of the person who makes the art playful. People, people making the most joyful, cartoonish inventions are making very serious things. Nobody will ever say that it’s all Steinberg, for example, wasn’t a very serious artist. Usually he makes things that make us laugh and they are they are comical and piercing and dreadful and dark at the very moment that they’re light. So he’s a serious artist making playful and highly amusing works. And that was true also from my point of view, looking at the work of Miro, for example. But it was certainly true of Calder. These are the act of making it an intensely serious thing, just the way the act of making something that we of feel is trivial, like a musical comedy. Oh, my God. It’s the hardest thing on Earth to make a musical comedy and to make everybody feel good going into it. Deadly earnest business. Enough to drive a person to suicide to do a thing like that. So there’s always the gap. There’s always the difference between the intention to make and and and the consequences which are for the benefit of the whole world.

Interviewer: We just run out. OK. Bring in the last Miyagawa. A difference between. Cut. Seriousness, childlike, or where do we say this, it’s child like versus by playful. Can you?

Brendan Gill: It couldn’t be anything more preposterous than.

Interviewer: I’m sorry. We need the mic on you, not me.

Brendan Gill: There couldn’t be anything more preposterous, really, than than the notion that if you are as an artist, playful, that you are doing something childlike or even people think childish. You know, it is almost the equivalent of saying I could do that myself or my child could do that. And so the seriousness of the artist is in the making of the thing. And if it happens that the making of the thing is something which we decide ourselves, the viewer, the thing is playful and that he has succeeded in being playful. This is itself a very serious thing which we take joy in. Homo Ludens the playful man, the man who is making playful ness but has nothing to do with childlike ness at all. It’s a highly intellectual process. And you wouldn’t even be able to think in the terms that we then say are playful. If it weren’t for the fact that you were deadly serious about it and there are 100 artists in history of whom you can say this over and over, over again, this is what you see in their work and this is what we respond to in their work. It adds to our life. It gives us this thing is this and this energy of joy, of what we call joy. What else can you call it? But it has nothing to do with being childlike. And of course, the way we think of Picasso or we think of Matisse, you might as well say that that Mattise is decoupage. You know, it was beautiful, just abstract bits of colored paper mache, childlike, are they childlike. Now that, you know, it’s nonsense. Well, anyway, Calder, I think, was always occasionally stigmatized by by by this notion that he was being not only childlike but childish. And that was just as far from the nature of his work as you could imagine going.

Interviewer: He was very prolific. Thousands and thousands of pieces. Yet he, as the first internationally famous American sculptor, he really didn’t reach fame or true prominence until he was in his 60s. Do you know? Can you give us a sense of what else was happening in sculpture?

Brendan Gill: I think sculpture has always been a very it’s been something of an orphan in new in the world of art from the beginning, and sometimes this is because the sculptors themselves from the from the convention of the academic sculpture is the only certain number of commissioners to go around. There only a certain amount of work to get done. And if you do win a commissioner, a particular thing, whether it’s academic or not, it may be a hundred thousand dollars. Five hundred thousand dollars. It’s a big investment. It isn’t like making a small painting or a watercolor or something like that. So I think there’s a certain amount of difficulty in getting your work done anyway. And so Calder’s particular kind of work and then the fame that he acquired and the well, as I say, fame is a corruption anyway. The success the self is based on his self-fulfilment. He was highly successful. He was self fulfilled. And then fame happened. But fame could perfectly well just just almost perfectly well not have not happened. I don’t think that Joe Jose Pournelle ever gained any particular fame for the first as a 60 years making his toy boxes. But but that had nothing to do with his success. I can’t imagine a man who felt more self fulfilled than Cornell. And I think the evidence is that the way Calder was also.

Interviewer: Let’s cut for a second. If you were to try to briefly describe Calder’s art to somebody who’s never seen ir how would you describe it?

Brendan Gill: I suppose I would describe Calder’s art almost in terms of animal nature and the quality in it that makes me always think in those terms is it’s primordial ness. Is the degree to which it seems to have come out of a prodigiously distant past. And to have arrived a perfectly self-confident among us at a time and place, it was took us by surprise. How could it not? But in both cases, both the mobiles and the stables, that one is an animal of a certain kind and one is the bird of another kind pterodactyl and mastodon or whatever you want to call them. And and but as I say, they they they spring from something that we must be at least as old as Lascaux. The beast on the cave or the walls of the cave or Lascaux are not unlike the kind of beast that that Calder was making for all of us. And that doesn’t describe it at all. Or somebody will ever seen them before. That will only be when I had said that then they might enjoy the shock of recognition. We’re seeing anything like that for the first time. It is astonishing to me that with his work, you feel it once the friendliness of it, whereas there are other sculptors, Mark Di Suvero for example, whose work at first you feel a sense of aggressiveness there and even of terror. And why not? There are big and strong. They’re bigger than we are, stronger than we are. And they may be going for us. And that was totally foreign to the effect the Caldler was able to create.