Speaker OK, I’m just going to let everybody know this is interview with Calvin Trillin. On December the 11th, 2002, Lose Contact. We were talking before and you might as well pick up on that back.

Speaker Could you describe the editorial process at times?

Speaker Well, when I was there, the editorial process, which is quite different from what it is now, was often referred to as group journalism, which meant that there was something called the news bureau in charge of a lot of correspondents out in the field and something called Time at It, which was a group of writers and editors and researchers in New York. And the idea was that that the information would come flowing from all of these correspondents, plus whatever the researcher could find in the library. And the writer would pull this all together and write his type. Timepiece. And in theory, the correspondent was really writing for the writer. Although it looked like a story. I mean, it started out as if it were a story. But and and also was the other important characteristic of it. I think it was very rigidly divided into sections, education, religion, press, national affairs. And people wrote those sections and there was, say, one education writer or five or six national affairs writers.

Speaker And there were senior editors who either had one big section like foreign affairs or what?

Speaker Just as I said, that would be no problem.

Speaker OK, yeah. It’s.

Speaker No, I’m not sure that one does for somebody to say, oh oh four says hang up. Yeah, that’s the one I know or else.

Speaker Right. But less so.

Speaker All right. You can put it in a jar or something. You know, I think the viewer who is right is not initiating this might hurt a little bit of a difficulty distinguishing between correspondant writer.

Speaker Oh, OK. So you could sort of take me Friant flow. OK. So OK.

Speaker Well, time had something called the news service, which was, which was basic.

Speaker Draw. You want to put in a drawer?

Speaker You’re going to trust that it’s going to go on. Yes, it’s OK.

Speaker Group journalism. Which is what this system was called, consisted of of an organization called Time Edit, which were which is made up of writers. The people who actually wrote the little stories that appeared in the magazine. I should say little, because they are mostly short pieces. Researchers who helped them do that. And then and then recheck them to make sure that they corresponded with something that could be shown as a source. I use that complicated phrase as a substitute for the truth because that those were not necessarily the same things. And an editor as the the making sure that you had a source to to back up what you said isn’t necessarily the same thing as saying something that’s true. I don’t mean that in a bad way. It’s just that those are different things. So time that it was a small group of people who never left the building, basically, except some of the back of the book writers say the show business writer might do his own reporting on a story. John McPhee was the show business writer for a wall or entertainment, whatever it was called, when I was first there. And he often on a cover story particularly, would go do his own interviewing. But generally, you would write about things that happened all over the world. You actually were just sitting on Sixth Avenue. You never left.

Speaker That was called time at it. And that’s where the magazine actually got produced. Then there was something called the news service, which was made up of reporters in bureaus all around the world. Time called them correspondents to make them sound a little better. But. They they wrote what were called files, which were sent to time at it. And then the writer would fashion those and whatever he got from the researcher who had been mining the stuff in the library and whatever he got out of The New York Times or or the Herald Tribune into maybe a 60 line story, which then went to a senior editor who either said write it again or changed it or actually did pencil editing and the old fashioned way, sometimes two or three versions. And sometimes the senior editor would get just irritated and just rewrite the story. He, of course, didn’t have time to read all the files of his section. Then the researcher would meet with the writer and and it was her job. And I say her advisedly because all writers were male and all researchers were female by actual policy. It was her job to get a read check and on top of every word to to be able to show some source, some what was sometimes called read check source for everything in the magazine. Those meetings took place at the end of the week when the writer was very relieved by that time, by having the senior editor and managing editor’s initials on his story meant that he was done. Then had to defend the story against the researcher in a way. And those sessions, I’m not sure if it’s fair to say often, but sometimes ended in tears. Researchers tears, writers in cry. They were men and women and this was group journalism. What it meant in in practice was and I did both ends of that. I spent a year in the Atlanta bureau for of time and in the early 60s during the civil rights struggle. And I wrote as what we called a floater for about six months. And that is a person who moves to kind of utility infielder who move from one section to the other as somebody took vacation or or went on a special project, was sick or something. And I spent about six months writing and what I think was then called nation or national affairs. At any rate, the way it work was that the correspondents worked very hard at the beginning of the week and the writers went to the movies. The writers worked very hard either Thursday or Friday night, depending on the section, and didn’t. And and then it all came together on something like Saturday night for some sections and Friday night for other sections.

Speaker There were some great advantages of the system in the sense that the writer in New York, without having to spend his time reporting anything, got an enormous amount of information sometimes from all over the world. And and had the the time to sit there and pull it together, write it whichever way you wanted to. The disadvantage of the system was that the farther you got away from what actually happened, the more power you had over the copy. So the person who had the least power over what ended up in the magazine was the person who would actually seen what happened. And and then it went to the writer who at least had read the file. This then went to the senior editor who didn’t have time to read all the files. And then it went to the managing editor who certainly couldn’t have read all the files for the entire magazine. And each one of those people that could add a paragraph if you wanted to, or take out a paragraph or or anything. So there used to be a saying that times stories read beautifully unless you happen to have been there. And then they didn’t read so beautifully. I think the sections also gave the magazine part of its tone because the religion section, for instance, was written by the same person for years, and he became quite familiar with all kinds of issues in religion. And he would have lunch with Luther and Liturgist and and have visits from the Labov ature PR people. And. And he would know quite a bit. And that would permit him to write in that sort of authoritative tone. That time became very well-known for the floater, which I was for six months. The utility infielder when the religion person got sick or went on vacation, would would come in from, say, show business the previous week or sports and literally to his office, to the religion writer’s office.

Speaker And as he sat in the chair, a an authoritative knowledge would come over him. We called it instant omissions as he settled into the chair. And somehow he was able to write with precisely the same tone as the regular religion writer, even though he had known anything about religion the week before.

Speaker He didn’t kill us. Did we get killed? But previously, when we were talking about the distance from the.

Speaker So let’s do the floater, OK?

Speaker The the sections, I think, became one element in in giving time the tone it had, which was a very authoritative tone. Time often use the phrase. In fact, it would talk about what a couple of people thought or what one school of opinion was. And then it would say, in fact, and then they told you what was really true. I think part of that tone had to do with the fact that the that the writer of the session actually did know a lot about the subject, particularly subjects that newspapers and magazines then didn’t cover very often. Education, religion, medicine. So he actually, the religion writer, actually met with Luther and Liturgist and read Quarterly’s about Presbyterian thought and and knew the Lubavitcher publicity people and that sort of thing. And and then he would go on vacation and the floater I was the floater for a while. The floater would come in. Maybe he had done show business last week.

Speaker You said. The other day I heard, so I occasionally I can hear. OK.

Speaker And then the floater would come in, say to the religion section, because the religion writer is gone. He had just been in show business or sports. And and as he settles into the office of the religion writer, this authoritative feeling about religion comes over him. I used to call it instant omniscience as he sits in the chair. He’s able to write with the same authority, even about, say, art. I, I, as a floater, was the art writer when I think was Stuart Davis a painter die. I know a lot about Stuart Davis. If he had died the week before, I would know nothing about Stuart Davis. Probably I’d never heard of Stuart Davis when I when I wrote the piece. So. So it just depended when you were there. That’s why I have a lot of weird, extraneous knowledge about Leupp colostomy. So when I was in the medicine section, things like that. But that tone sort of went through the magazine.

Speaker Tell me a little bit about the sort of the.

Speaker The corporate culture or the social corporate, less social culture?

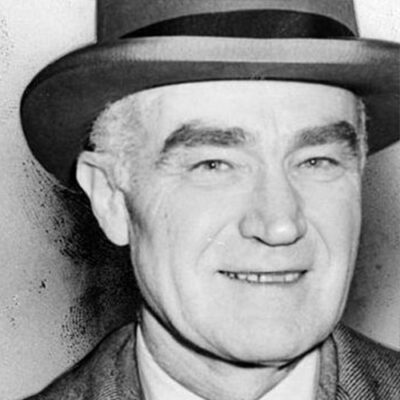

Speaker Well, I think it evolved from the Yale Daily News. Briton Hadden and Henry Luce were were editors of the Old Daily News. And the Yale Daily News building is now called the Briton Hadden Building.

Speaker And neither one of them, I think, wanted to be what was called on the Yale Daily News, at least by the time I got you downstairs as opposed to upstairs. Downstairs was the business people. That was the business department downstairs. Upstairs was the editorial department.

Speaker And Henry Luce, I believe, to the day he died, was listed as editor in chief of All Time magazine. He was not never publisher or president or anything like that. I think both of them were interested in in the in being upstairs and. I think the the whole idea of separating upstairs from downstairs was very strongly in their in their minds, even though obviously if the man who essentially owns the company is called Ed, there’s some some slip over there between what they used to call church and state. And but I think they genuinely felt that there that there ought to be you have to remember when they started this. Most newspapers and a lot of magazines were pretty corrupt.

Speaker I mean, there were people I mean, there there was a lot of interference with having to do with business. And you could argue about what what’s going on now and maybe the same thing.

Speaker But the odd thing also about the corporate culture now that I think about it, is that Time Inc. Even though they had the march of time, they had the book division at one point that was pretty clearly in the magazine business. And in fact, two or three times when I was there, when they sort of branched out, there was some sort of educational thing. I can’t remember what what it was about two or three other things. They didn’t do very well. And I think that that that Luce’s instincts were to sort of stick with what he knew. I mean, ironically, this has become. I don’t know. Eight tentacles of a huge octopus. But I don’t think that was Lucy’s notion and I don’t speak as anyone who was privy to his thoughts. But, I mean, my guess is that that wasn’t Lucy’s notion and certainly not Haddon’s notion.

Speaker Did you have any. I lose.

Speaker I had very little contact. I think I could probably get them into maybe three or four times that I.

Speaker I was there one summer when a number of people were working there for the summer who were or had been college editors. And it wasn’t any specific program when we were hired, but they sort of pulled it into one during the summer and they decided we should have lunch with various people once a week at time and ask them what we’re called. And I’m sure of this, quote, probing and provocative questions. We were encouraged to ask probing and provocative questions. So and we eventually worked up to having lunch with Luce and Roy Larson, who I believe was the first person hired by by Lucent Hadden. Certainly a very early hire was then probably something like the president of Time and.

Speaker And, of course, being there for the summer. And in some ways, it was true, even even not for the summer, I once compared the time riders that the sort of attitude of time riders as being sort of like enlisted men from Princeton in the army. That is, they knew they weren’t going to make a career out of this and they kind of suffered along and found it ironic and sometimes didn’t do much about leaving, sometimes ended up making her out of it. But certainly the summer people were very much that way. And so we asked as probing and provocative questions, questions as we could find. And I remember asking Luce why. Joe McCarthy time didn’t like was always described as swarthy. And Richard Nixon, whose beard was about the same heaviness, was never described as worthy and why Dwight D.. Eisenhower always was described as striding briskly into the room. I can’t remember much of the answer except that that he said that that Eisenhower was a military guy and actually did stride rather briskly. But I met him at that lunch and he was he was great. He was open. He was he was not an articulate man. He didn’t exactly stammer. He just had the words just were not easily flowing out of his mouth. And the very always very pleasant, respectful and. And then I saw him. I worked for something called the one summer. I guess it was the summer. Maybe was the same summer International Industrial Development Conference that time Life International put on in San Francisco. And and he was there in attendance. So I would see him, but not really interact with it very much. Then I once saw a memo from him, a memo from only one memo I’m sorry, didn’t save it, although maybe I was supposed to pass it on to everybody else in the section. I think it was when I was floating international affairs during the Kennedy administration and it said and I can’t remember what little scandal was going on in the White House. But I remember he said in the memo it was a typed memo with his initials written. That the burden of the memo was that we’ve been been taking this too lightly, treating I remember the phrase was treating the Kennedy boys like children with their hands in the cookie jar. And it said that what what had been done and I can’t remember what it was, was truly wicked. And I was I was taken by the word because with the exception of something like Wicked Curveball, I had never heard anybody call anything wicked. I mean, that was I thought that was a real missionary son’s view of the world to call something wicked. So I didn’t have any I knew people who knew him, who were close to him, like Tom Griffith and Dick Klarman.

Speaker But I he was I was very junior person there. Well, while he was.

Speaker Well, what.

Speaker How did how did time express it’s nice.

Speaker I mean, well, time. Time express its bias. A lot of it was in adjectives the way they describe people. And. Spy magazine descriptions of people.

Speaker I always thought I never asked them, but I wish that was sort of a parody of old Times style where they always described Donald Trump as short fingered vulgarian. Donald Trump. I mean, this was a lot short fingered, came from. But bosomy dirty book writer Shirley Lord. These things were they were they used the same phrase gap-toothed that sort of thing.

Speaker Time did that. A lot of time was. And they and they would say after something summing up in fact. And they would tell you what what what the truth was. I worked in national affairs and I thought that my tenure there would probably be very short because of political problems. But I didn’t have I worked for a man named Champ Clark. He was the senior editor. He was. And he he was a Republican. And he didn’t make any bones about it. And unlike some of the people in the top management who would sort of pretend that we were being fair minded, but somehow all the facts always came out on the other side. He was he was he was Republican. But he was also if you went in and said if he changed your copy to say something, went in and said, champ, this this isn’t supported by the facts.

Speaker He would say he was.

Speaker He died rather suddenly. I mean, he was he was frail, but but, you know, it was you know, I had lunch with him last year, about a year ago, I guess. And he was you know, he’s very articulate in spring, I think in the spring, you know.

Speaker You know, he he’s sort of spoken to him when he first spoke to you right around January. Yeah.

Speaker The answer is. Yeah, wonderful man, very balanced. And and he was interesting in that that with all with all of the complicated. Conspiracy theories about why. Time was fair. In the end, the Kennedy Nixon campaign was really. And everybody said, oh, Joe Kennedy had talked to Henry Luce and all this concept, it was that the GRIF was. Was in charge, that the managing editor was ill and that he was made. He was acting managing editor. And he’s just a fair man. And it was, you know, down the line.

Speaker What about the politics of the mayor? We will will hopefully grip the politics of the magazine. This strange. You know, when I was thinking about the culture, the strange thing that that, you know. Lewis was a dyed in the wool Republican, but a lot of his riders were liberal.

Speaker The dynamic didn’t make, I think, uncomfortable, and I don’t know exactly how people dealt with it on a long term basis. I thought when I got into foreign affair, I mean, national affairs or nation, whatever they call that section, that I would be gone in in a week or two.

Speaker But I found that if you if you just wrote the piece and wrote it the way that you thought was a reasonable way to write it and not for or against anybody, and you could back it up that if, say, the top editor was the was often the managing editor wrote in a little sentence or or changed it or changed an adverb or something.

Speaker If I found that if I could go to the senior editor with a man named Champ Clark, who was a who himself was a Republican and quite open as a Republican, but a fair man. And if you could say you can’t really back this up. This isn’t true or or this is unfair. I would go in every, I don’t know, two or three weeks with something. But I realize it sort of wears you down. You know, that there was a tie and I only did that for was only in the section for, I don’t know, six months, maybe five months. I don’t think as long term it would have worked out. I think some of them went to sections where the politics weren’t obvious and they were only obvious because we don’t know from my question.

Speaker Oh, I think some riders who had political problems or put politics different from the magazine solve that by by avoiding those sections.

Speaker The sections that were overtly political. National affairs press, oddly enough, to a certain extent, was was very political and in foreign news to some extent. But, you know, to write an education story or religion story, politics really didn’t enter into it. I should also say that Luce’s politics. By today’s standards were rather moderate when he was a Republican, but he was an internationalist. He was very much against segregation. He was against McCarthy. So when I was a reporter in the South and virtually all of my time, I was in the field for four time, was in the south, and virtually all of that time was on the race story. That’s almost all I did. Probably 90 percent of what I did. I felt very comfortable. I felt we were on the same side. Certainly the white Southerners thought we were on the same side because the time was was much more hated in the South. And someone told me once that a friend of hers had gone to the south for the New Republic and people were very nice to him. And I said, yeah, you’re right. I had never heard that New Republic sounded good to them. Nation sounds even better. But time and I think look magazine particularly hated by by white southerners. So.

Speaker So sometimes it really wasn’t a problem. You know, I mean, sometimes if you think about the Republican Party.

Speaker The policies the Republican Party now are the people who who control the Republican Party loose was not a right wing person. Then he seemed to be a right wing person and there were people working for him who were to the right of him.

Speaker So it was it was complicated. And somehow when when I was first there, you think, well, maybe you could take care of this by, I don’t know, going to Newsweek or something. But how many people did it didn’t. I think that people with with political strong political views either avoided recession session or avoided working for time and. Reporters, journalists and general. Oddly enough, I don’t think usually have strong political views. I mean, one of the one of the idiocies of of right wing commentators saying, you know, 78 percent of the reporters in Washington voted for Clinton or 84 percent or something is that, you know, they voted for him, but they’re not really ideologically involved with him. And and they’re much more interested in a good story than they are and who wins. So I think it’s true of a lot of people at time. I have to say that the. Who? Who the time riders were. Changed over the years. At the at the beginning and even fairly late into the probably. I’m guessing maybe 40s and 50s on a lot of the time writers were I suppose you think of them as maybe failed Ivy League literati. They were people who had gone to Yale or gone to Princeton or Harvard and and maybe wanted to be novelists and. And ended up writing for time, often without a lot of experience as reporters.

Speaker By the time I left the national affairs section in 1963, three of the six riders in the National Fair Sections were former stringers from the Minneapolis Star Tribune. And people who study the culture of time actually could tell you a tipping point where the newspaper people. Took over from the sort of Ivy League people, and there were some people who were both, I think, auto for Boehringer or maybe even Roye. I think Roy Alexander was maybe the first newspaper managing editor and auto for Boehringer, I think flipped from the Post-Dispatch. But but also going to Harvard, I think. I’m not not sure. But it was a different it was a different group. But I was I was amazed once when I was about to leave, just before I went to The New Yorker, I read a book by John Brooks about time, which was called The Big Wheel.

Speaker It was a it was a it was a novel, serious novel about a guy who worked in a newsmagazine that was very much like time. And John had worked at time and it was assumed it was time, although he didn’t make a big thing out of that. And I’m not even he certainly didn’t call it time. And you may not have called it anything. And. And I just happened to see it on a shelf, probably as I’ve gotten to somebody else’s office or something. And I and I read it. And Tom Griffith, who had been there for, I guess since the war, maybe since the 40s, said, what do you think of it? And I said, I rather enjoyed it. I was surprised that it wasn’t more about time than than it was. I mean, I don’t mean to hold on to journalism or anything. It’s it’s a fiction. And he doesn’t claim it’s about time.

Speaker And he said, what do you mean? He said, like, there was a story conference where the senior editor sort of tormented. Oh, there was a story conference in the novel that seemed to me the farthest from furthest from anything I would had experienced a time. And in in this story conference, the senior editor who runs the story conference and you sort of pitch him ideas, there’s a little ritual of a guy reading off of a list of possible stories that really tormented the one of the writers. And in the way that you hear about professors at at Harvard Law School bullying the guy who’s not quite prepared and and all that. And I said, I mean, that was an interesting scene, but nothing like that could ever happen at time. And Tom said. I was at that storico and. And in fact, John’s book was was really romantic. Well, oddly enough, I found it unrecognizable. Time it had changed that much from when John wrote it, which I suspect may have in the late 40s to the time I was there, which was the early 60s.

Speaker Is a more general question. Up again.

Speaker First of all, growing up in your household, did you get TIME magazine? Did there ever come to your house? Did you?

Speaker I don’t remember if we got it. I remember that when I went when I called my father and said that I was. Thinking about going to The New Yorker. Actually, I was gonna go to The New Yorker, but I said I was thinking about going to Archerd if I wanted to kind of include him in this decision. He said he thought The New Yorker. I mean, time he was. He was so aware of time compared to The New Yorker. I mean, it was even if you didn’t get it. And I can’t remember if we got it. I don’t think so. I think we’ve got mainly magazines like The Saturday Evening Post and Ladies Home Journal. Life magazine and life probably. Life was I think life was more of a of a. Impact on the culture than than time. I mean, you waited for life every week because they had those pictures that nobody else had. And even if some people had shown them and sort of grainy newspaper, black and white, there was nothing like that page and a half shot and life. Life was a was a very large cultural force, particularly before television. And I think time. Was I think the idea of time was that it would save time. I think that that when loose and had an invented time and I do think they thought it was an invention, just like the Wallis’s thought of the Reader’s Digest as an invention. I, I think the idea was that that business man who really had a lot of responsibilities could take a look at this magazine. It was it was sectioned off. So if you want if you just wanted to read about press, you could read the press section or if you and he could do it rather quickly. And and the stories had a beginning and a middle and an end. So they were entertaining. Unfortunately, life doesn’t always organize itself in weekly stories. So sometimes there was a favorite phrase at time, which was at week’s end. At week’s end meant we’re gonna have the next version. Next chapter. The next week. But and that and that formula of time where there was often a snappy quote at the end of the first paragraph. And it kind of came around to the end, made it easier for him to read.

Speaker So it’s not only shorter, but it was more entertaining. And and I think a lot of the style that sort of clips style came from that just trying to save space. So you so you don’t say Joe Jones, the author. You say author. Jones and and that whole snaggletooth business is you don’t say author Jones, who is a man of medium height with separation’s in his teeth or something like that. You say Snaggletooth author.

Speaker Jones and you’ve got it. You really cut it down quite a bit. But at any rate, I think that that was an invention of time. And of course, I remember writing a column once when, oh, maybe 10 years ago when Time adopted the advertising motto. Take time for time or make time for time. I think it was make time for time, that was the slogan. It was astonishing because what it really meant was that the attention span had shrunk enough over the years so that a magazine that was invented to save time was now thought of as. Hey, it’s really worth taking all of the time it’s going to take and it’s not that the magazine had gotten longer, it was it was simply that the notion of of how long someone’s attention could be held had changed. But but life, I think, before television came, had had a huge effect. If you remember those things where it said life visits something or other. And I did a a book about a classmate of mine at Yale who was the sort of person. We kind of thought we’d be president who committed suicide in his 50s. And among all of the things said about him, he was a Rhodes scholar and he was by Kalpa. And he was he was a swimmer and cetera, et cetera. Is that life covered his graduation. Alfred Eisenstadt came with Michael Arland carrying his bag for him and covers the graduation list. A huge impact.

Speaker And I think I said in the book that if you think of CBS and ABC and NBC and all these killings all wrapped up together, that was the sort of impact that that life had when it rubbed up against sort of an ordinary American seen.

Speaker How influential then, do you think? You know, during a certain period was Henry Luce.

Speaker Well, I think it is very influential here. He was certainly influential politically. I mean, I think that the that the loose magazines on the question of China, which was a particular bugaboo of of of loosies, I assume, because of his background, although I don’t I don’t know that for a fact. I think that the things might have been a lot different in and about our China policy. I hadn’t been loosening of certain policies like that. I think he had a big effect on journalism. For instance, a lot of people.

Speaker It seems normal now, but but some of the some of those sections the time had were on subjects that the press ordinarily didn’t cover.

Speaker Education and religion, science, medicine, those were really the places where you’d read about. Say medical things or or or scientific things or or educational things. Time and then Newsweek, which was sort of a knockoff of Time.

Speaker And so I think I think he made the subjects. He made people pay attention to those subjects, I think. I don’t know how much influence he had on on the Republican Party, because it seems to be a totally different place now. And I think he would be now sort of a suspect in the in the Republican Party, but in the way he perfected the.

Speaker Culture, the middle right. The so-called middle ground, the middle ground between time and life. Was he influential in terms of how how people thought or what they’re thinking?

Speaker Yeah.

Speaker Oh, I think I think he was because because that’s where I mean, I remember when I first went to England, I had this weird some weird job for time before I went in the Army.

Speaker It’s a busy morning here. OK. OK.

Speaker Critical.

Speaker When when I when I was first in England, it was a summer after college and I was waiting to go in the Army and I had this kind of. Temporary job with time in London.

Speaker I remember for the first time the English press and people would refer to time as sort of the reflection of of middle class views in America. I hadn’t really thought of it before that. But I think it’s true. I think that that are the people’s ideas of. And there were a lot of people who who basically were written about by you because of the back of the book sections, particularly written about by time and not not by other people. I mean, they were well-known because of time.

Speaker I mean, somebody maybe who owned newspapers or somebody who was a religious figure like Father Murray or I can remember his name. He was a big, loose guy. He was on the cover of Time. And being on the cover of time meant you were famous. And you have to remember, a lot of this happened before television. So being on the cover of TIME was yet.

Speaker Well, you bring something up that time.

Speaker Time also, if you can tell us about this time’s. Approach to news is being news 12 to people.

Speaker Right. I think that was that that was one of the. The notion that you could tell a story through a person, almost no matter what the story was, was kind of central to to the time approach to things. And I would say I’m not sure this I’m not a historian of the face, but I but I suspect if you look back through the time covers. It was fairly late that you’d find a cover that had anything but a person on it.

Speaker So that the so that the cover story, which often was about foreign affairs or orchestras or something, was almost always told through a person. And time and time had something that that newspapers call the nut graph. Which is usually about the second or third paragraph. If the secretary of state was on the cover, you didn’t need to not graph. He was the secretary of state. But.

Speaker If if, say, the he had a racing driver on the cover around the third paragraph in a time cover story would say, although some racing drivers. Have one more money and some racing drivers have won more races. No racing driver so symbolizes the so and so and so on. So that’s the nut graph. This is very common in newspapers when you see people, particularly out in the middle of the country from The New York Times. It’s basically the answer to the question that’s implied in the story. What is an important journalist such as myself doing in a place like this? Or why are we putting this guy on the cover rather than the secretary of state? So it thought if you wanted to do with a story about time thought, if you wanted to do a story about.

Speaker Classical music in the United States, the big story, the way to do it was to find that iconic conductor or Cleveland Symphony and put him on the cover. And in a way, the nut graph at time, which which we call the nut graph.

Speaker But that’s a newspaper term, but was an extension of the cover conference where various editors would be arguing for what became really their candidate. I mean, the guy, the senior editor who presides over sports, among other sections, is pushing for the racing car driver. And the guy who presides over music, among other sections, is pushing for the for the conductor of the Cleveland Symphony. And that gets into the story at the end. This is why we have to have this guy. But, yes, it was always.

Speaker Through through somebody. And remember, there was a time I don’t see him in the stores anymore. Maybe I’m lucky enough not to go into those kind of stores, but sort of souvenir stores. They used to sell a mirror that had that red border of time and and the logo of time and. And so when you looked in the mirror to shave in the morning, you were on the cover of Time. I mean, it was it was culturally very important in America. And you still identify people as being on the cover of time.

Speaker To what extent do you think.

Speaker Oh, I think the question of of Luce’s view of the world compared to his magazines. I think in some ways they did.

Speaker In general, politics of time reflected loosest politics, which was in his politics, were based partly on the notion of what he called the American century, a winning back China in some way or another. And what I think would now be called moderate Republicanism, I mean, free market, but. But not. He was never a hater. And the abortion issue wasn’t around in those days. And simply because there weren’t no there were no abortions allowed. And he was a serious man. I mean, there was a lot of kind of serious, serious, heavy thinking coming from Lewis, who’s very known for asking constant questions to make keep himself informed. There was a sort of a almost self-improvement kind of Protestant view he had about that.

Speaker And I think that’s reflected in life in all of this stuff, these huge pieces by Winston Churchill about the future of the world, the that sort of thing. I think some of that, on the other hand, loose, even if he called himself the editor in chief. He owned the place and and and I don’t think a place that was just reflected his personality could have sold a lot of magazines.

Speaker I mean, he wasn’t a light fellow. And and so you had to have a certain amount of of of pop culture and a certain amount of things that drive a certain number of things that really didn’t interest him very much. I think so. But but I think he I think he meant to have it because he thought he was right. I mean, he was he had a kind of a I think a religious view.

Speaker You know, I think. Tell me if you can curb or not. I always got this sense, particularly in the 50s. Again, sort of tell me quite.

Speaker That life had a way of representing Americans to America, America to Americans that gave.

Speaker People with certain self-defined. Do you think that’s fair to say, do you think? I’m thinking predicting life because of pictures and representations. I think it’s fair to say that he regretted.

Speaker Sort of tried to be a mirror and a certain a certain image that he put into the eye.

Speaker Well, I think in the case of life, that life did try to be a mirror. And and, you know, you can never tell, you know, a lot of a lot of mobsters now act the way they think they’re supposed to act because of the Godfather, you know, and and which was made up didn’t have much to do with it. And so you it’s hard to tell whether Americans were like what was in life because it was in life or whether it was in life, because that’s what Americans were like. But but it was very broadly American. And I think particularly that that that feature they had, life goes to a something. Life goes to a Fourth of July picnic.

Speaker Or life goes to a wedding that really just went. And then when they hit town, it was so exciting that these people were there. And in life, really. And I think that’s one of the big effects Luce had on journalism was. And, of course, you know, in a way, the time had to be coming because the technology was advancing. Is that is that he and. Sort of, sort of at the same time, look did roughly the same sort of thing, but not quite as effectively. He made photography sort of front and center. Almost starring role that that photographers became sort of dashing. I mean, the Life photographer almost was like a British pilot in the Battle of Britain or something. You could almost see the white scarf around his neck. Very romantic figure and wonderful photographers often. And fantastic photography. But until then. And as I say, it should be said that look wasn’t roughly contemporaneous. Until then, photography hadn’t really entered into the equation much in journalism. And it was really a pretty crude art, particularly in magazines and even in time.

Speaker It’s hard to remember now that time started using color only relatively recently. And they’re actually used to be a senior editor when I was there who was called something like The Color Project Guy. And about twice a year they did two or three pages in color. Otherwise, it was black and white.

Speaker And and in life, life really made made these people like Eisenstat and David Douglas Duncan and Margaret Bourke-White and these people renowned figures. And it made their photography important. Now, it would have been important anyway. And I think fortune to some extent was the first. Really serious coverage of business, which still, I think is covered in incomplete ways because businesses are are simply harder to cover than than government or something like that. But so I think he had an impact on on on all of these on journalism as well as on on American policy.

Speaker When you were a young man at Yale was a Briton Hadden building. Right. Right. What did.

Speaker What do people know about Britain?

Speaker The legend of Britain, Hayden, was that Britain, Hayden was the sort of quirky genius and loose was the sort of square guy. Now, I have no idea whether this really conforms to fact, but but that was the end. I remember there used to be a guy at time who was sort of an historian of time who I talked to a lot during this international industrial development conference in San Francisco. Can’t remember his name. That’s what he did. He kind of collected things and looked back on the history. I don’t know if he ever wrote anything about it. And he always said that that was just not true. But I don’t know. I haven’t. I have no idea what. But certainly the the legend was that Hayden was the guy who made up the style and and love to coin words, and that that loose was the guy. And they used to take turns, I think, as I remember being upstairs or downstairs in time, being church or state and and as I remember. Hayden was the guy with the I mean, certainly the legend was it was that Hayden was the guy who was really comfortable in the editorial part of it, and loose was the one who was comfortable in the business part of it, even though Loose always was very interested in ideas, very interested in making some impact and ideas, and he gets a kind of missionary upbringing. But now I don’t know whether any of this is true about Hayden. And the only book I’ve ever seen about him was written by his cousin and and which I mean, doesn’t negate it necessarily, but it was a long time ago. So I don’t know.

Speaker But that was that was the reputation.

Speaker It was also I mean, also I think that the other thing about time is that among newspaper people. Time was definitely thought of as not quite respectable place to work.

Speaker It was it was thought of and it was thought of as because of you didn’t write your own copy or you wrote somebody else’s reporting or and that it was had an obvious political bias that that’s faded over the years. But there was definitely a time when when, say, at a press conference or read a story where there a lot of reporters that that time was definitely thought of as as sort of a place where people had gone maybe for the salary or the or the security or something like that, although I think that a couple of things happened, one of which was it turned out that the salaries weren’t they weren’t that great.

Speaker There was a time after I left when all of the people who were writers in New York who were called not writers because the nomen culture was always a little bit inflated. They were called associate editors or something like that. But they were actually like the guy who wrote the religion column or the guy who worked in the foreign news section. I went to lunch and and through their salaries into the middle, I mean, wrote down anonymously their salaries and threw them in the middle of the table and and found that in the first place that there was a great disparity in the salaries and also that they weren’t making that much more, if any, more than than people on newspaper. So I think a lot of different things happened that change the culture.

Speaker We were talking earlier. He could tell us a little bit more about sort of the.

Speaker The clash of the not so much interested in the office affairs. Right. You just sort of the the class clash of sexes in the set right up sex.

Speaker Well, the setup was was really quite specific and open. I mean, it was it was that if you were female, you could be. A researcher at time, and that was it, time edit at least, and in the bureaus, there was a maybe a little more flexibility. Certainly nobody would. A woman wouldn’t be in the Washington bureau or or be a bureau chief or something. But I think that before there were women writers and time at it, there may have been a couple of women in the bureaus often. Oh, you know, the person who started out as a stringer and sort of got so that she was doing an awful lot of the work and eventually was taken on of the bureau.

Speaker But sort of accidentally when I as I was leaving Josie Davis, Johanna Davis started writing in a kind of a sub rosa way.

Speaker She literally was not listed as a writer on the masthead. She was listed as a researcher. And I think she was the first one. So it was it was very split. And, of course, all the editors were male. And the people who worked as head of the researchers were it was almost like the head nurse in a hospital, which, of course, in those days they were all female. The head of researchers was female. The library people were few. It was all it was all pretty cut and dry. And and I and I consciously I mean, I think partly, you know, in the times when when I think and I’m not sure of this, I was talking to somebody the other day who is doing a piece on on fact checking. Again, I think that was invented at time. But I’m not absolutely certain, but whoever invented it. And and and I always was told that it was Britain hadn’t invented it with the idea that this sort of energy would come out of having a male writer and a female researcher, the researcher, even though she did send out the queries to the bureau and gathered up the stuff from the library before the writer wrote the piece. Her main job and the job that she was sort of thought of doing was making sure that the piece could be backed up by facts at the end at the end of the week. And in that case, she met with the writer, not with the editor. And the editor wasn’t there was just the two of them. And these were often emotional and meetings that sometimes ended in tears. Because you have to remember, the writer sometimes had written the story two or three times and and also in order to get that last part. Last time finally done. He may have fudged a little fact to help him with his transition. OK. Just to get from one paragraph to the next. But now he’s got the senior editors initials on it and he’s got the top editors initials on it and he doesn’t want to write it anymore. And it’s his story. And he’s defending and against against her. And she’s going to get it if she let something by that that isn’t checked properly. She’s going to have to fill out what’s called an errors report when some guy in Des Moines spots this and sends in a letter. So she’s very eager to have everything checked. The fact that, in fact, resources might not be any good.

Speaker There was a wonderful piece written, I think it was in the Atlantic, may have been in Harper’s by a man named Auto Friedrich, who worked at time and also worked at Newsweek, a wonderful writer called There Are O Trees in Russia. And and his notion is that the in the first place is the senior editor wrote in, there are o trees in Russia in this story and not not the guy certainly who was the reporter and not the writer, the senior editor or maybe even the top hat or wrote in.

Speaker There are o trees in Russia because he finds it an interesting fact. And the and the researchers. Job is to justify that statement. Fill in the O with with some numbers and justify it. The fact that saying how many trees there are in Russia totally skews this story in the wrong direction. The story about the Russian wood industry or something like that is none of her affair. She doesn’t care about that. The fact that it really isn’t a relevant fact that it that it sets your mind off in the wrong direction, that that it really kind of kind of ruins the story. She doesn’t care about that. That’s not her job. Her job is to be able to point to some source and say there are 60 billion trees in Russia or something like that. And according to Friedrich’s piece, if you trace her source a lot, it may. You went back to another time story a long time ago. Some desperate researcher came up with that. So these were these were tense meetings often. And I think they were designed to be to be tense meetings. Actually, when I came to The New Yorker, all the researchers, which are called fact checkers at The New Yorker were male.

Speaker It’s just the opposite. And the writers were mixed. You know, I, I, I mean, particularly you can when you think of him in the context of the people who were around today. It’s.

Speaker You know, he wasn’t exactly the monster that some people thought of him then. I mean, it’s I mean, compared to. No, it’s not Trent Lott. This is not a this is not you wasn’t a hater.

Speaker And he and he had a lot of faith in the American free enterprise system. But and and he was really willing to to use his magazines to to back up what he believed even in an unfair way. I think that’s certainly true. But. But I don’t I don’t think of him as his evil or anything like that.

Speaker We’re just reading this reading, and you want to look up and look at people, look right into them.

Speaker Behind this latest, most incomprehensible time, enterprise time enterprise is, of course, one word looms as usual, ambitious gimlet eyed baby tycoon Henry Robinson Luce, co-founder of Time Promulgate or a Fortune Potente and Associated Radio and Cinema Ventures. Looming behind him is barely able tumbled down Yale man Ralph McCalister, Ingersol, former Fortune editor. Now general manager of all time enterprises, descendant of 400 famed Ward McCalister, littered his desk with pills, onions, Kleenex. Socialite Ingersol his times. No one hypochondriac. Certainly to be taken with seriousness is loose at 38, his fellow man already informed up to his ears. The shadow of his enterprise is long across the land. His future plans impossible to imagine, staggering to contemplate. Where it will all end knows God.

Speaker At times, like this guy was blessed with wealth.

Speaker The interesting thing is that is that is that when something would happen, a time in, I don’t know, middle 60s and say one of the tabloids would do a piece on it.

Speaker They would do it in what they thought was time style. And it really was walk out Gibbs profile of Henry Luce style. I mean, that became the the idea of what time style was and indeed, really what those kind of weird things, those kind of snaggletooth things had faded away usually by then.

Speaker Let’s try to shift we shift the magazine a little bit. OK. So we’re seeing less.

Speaker So would you maybe actually let us know this? Put this over here? Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker Oh, Campbell’s out.

Speaker Yeah. Josh.

Speaker OK, we’re rolling, right? Let you just read the first paragraph and just read it straight for you. OK, stop and say OK.

Speaker Behind this latest, most incomprehensible time, enterprise looms, as usual, ambitious gimlet eyed baby tycoon Henry Robinson Luce, co-founder of Time, propagator of Fortune Potente and associated radio and cinema ventures. Looming behind him is berley able tumble down Yale man Ralph MacAllister Ingersol, former Fortune editor. Now general manager of All Time Enterprises, descend into 400 famed ward McCalister littered his desk with Pils engines. Kleenex socialite Ingersol is Time’s number one hypochondriac. Certainly to be taken with seriousness is loose. At 38, his fellow man already informed up to his ears. The shadow of his is long across the land. His future plans impossible to imagine, staggering to contemplate. Where it will all end knows God.

Speaker Just.

Speaker To the.

Speaker OK. The two children.

Speaker Yeah. What do you think about that?

Speaker I hope will just little boy doesn’t need it. Actually the.

Speaker But this is a hard at times. This is a different. All right, Steve.

Speaker Surrounded by a resplendent guard of fascist mounted police, a lavishly decorated coach slowly ascended the Cappellini capital capital line.

Speaker I never heard that before.

Speaker OK, I start over with capital line seven. I think it’s the second highest dry. Actually, I never heard of it. OK. Here we go.

Speaker Surrounded by a resplendent guard, a fascist mounted police, a lavishly decorated coach, slowly ascended the capital, capital, capital to line the capital line.

Speaker Capital lined. All right. Now, a capital line.

Speaker It’s easy, just like if it’s a capital line railroad. Okay. Surrounded by a resplendent guard, a fascist mounted police, a lavishly decorated coach slowly ascended the capital line hill, famed cradle of Imperial Rome, as the coach drew up before the capital itself, dictator Premier Benito Mussolini regarded it benignly and extended a cordial welcome from a balcony of the capital itself.

Speaker OK, let’s try one more time.

Speaker You know, there are two capital itself’s in this paragraph.

Speaker Is that true? It’s terrible, but it’s true. OK. It’s been bothering us since then. That’s right. Can we do a little faster? OK.

Speaker Just tweet.

Speaker Oh, I see. Maybe a border, possibly sort of go.

Speaker Surrounded by a resplendent guard, a fascist mounted police, a lavishly decorated coach, slowly ascended the Capitol line Hill fame, cradle of Imperial Rome, as the coach drew up before the capital itself, dictator Premier Benito Mussolini regarded it benignly and extended a cordial welcome from a balcony. Start down there somewhere. As the coach drew up before the capital itself, dictator Premier Benito Mussolini regarded it benignly and extended a cordial welcome from a balcony of the capital itself.

Speaker Like an invisible ectoplasm. Surrounded by devoted spiritualists. The credit of the Japanese empire was under scrutiny last week in a hollow square of green covered tables surrounded by the National Policy Council. Without a constitutional quiver in his freckled right hand. Franklin Roosevelt last week signed the labor disputes bill, then lighting a cigarette. He leaned back and dictated a statement to the public. This act defines as a part of our substantive law. The right of self organization of employees in industry.

Speaker Let’s do that one more time. Shift a little work to the camera, very.

Speaker Without a constitutional quiver in his freckled right hand. Franklin Roosevelt last week signed the labor disputes bill, then lighting a cigarette. He leaned back and dictated a statement to the public. This act defines as a part of our substantive law. The right of self organization of employees in industry.

Speaker Frank, 22. Is impossible to do him with just one look at the camera within. Yeah. OK. I think that was all dead. OK.

Speaker Without a constitutional quiver in his freckled right hand. Franklin Roosevelt last week signed the labor disputes bill, then lighting a cigarette. He leaned back and dictated a statement to the public. This act defines as a part of our substitute law. The right of self organization of employees in industry.

Speaker Let’s if we may. Let’s go back one more time to the other two.

Speaker OK. OK. Service. Yes.

Speaker I loved right across the other page, it says he is Henry S. Johnson, a slim long nose lawyer, a man with darker lawyer.

Speaker A man is a great phrase. Whoever thought of that?

Speaker I see with dark room full of amazing just.

Speaker Who is the governor of Oklahoma? According to the last vote and the general impression of people outside of Oklahoma, he is Henry S. Johnston, a slim, long nosed lawyer man with dark room spectacles.

Speaker OK.

Speaker Now, these surrounded by a resplendent guard, a fascist mounted police, a lavishly decorated coach, slowly ascended the Capitol line hill famed cradle of Imperial Rome as the coach drew up before the capital itself, dictator Premier Benito Mussolini regarded it benignly and extended a cordial welcome from a balcony of the capital itself.

Speaker Like an invisible ectoplasm, sir. OK. Like an invisible ectoplasm surrounded by devoted spiritualists. The credit of the Japanese empire was under scrutiny last week in a hollow square of green covered tables surrounded by the National Policy Council.

Speaker I can’t imagine what that means. No.

Speaker It was under screwed in a hall pressure washer, really, just for cameral three room Tom.

Speaker Market newsroom tunc.

Speaker And room tone for trilling with small engine running.