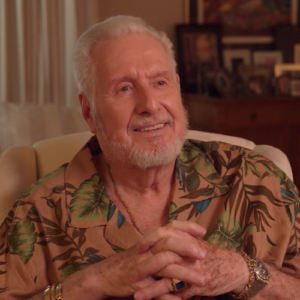

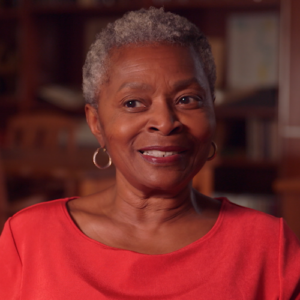

Charles Strouse: Charles Strouse I’m a composer, uh, I was known most for my Broadway shows, and, uh, I’m sitting here being interviewed.

Interviewer: Golden Boy has one of the greatest beginnings of a musical, And I just want you to know, that’s my opinion in Golden Boy’s Night Song, sammy sings, “I stand and wonder who the hell I am.”

Charles Strouse: Who the hell am I? That’s okay.

Interviewer: Well, who was Sammy Davis Jr?

Charles Strouse: Oh, wow. I didn’t think you were going to hit me with such a question. I knew him well, and yet I didn’t know him well. Who was Sammy Davis? I knew him well. And yet I did not know him well. He partied every night and almost demanded that everybody join him. So I’m tempted to say maybe he was lonesome, but he gave an opposite impression from that. But he could not stand still. Something I understand, but from another point of view. And he had to be the center of attention. He had to be when he was performing, he was uncomfortable unless he was in front of the stage, the source of a great deal of arguments among us, because sometimes the scene would be directed so he would be at the side or he would not be lit. He was very uncomfortable doing that. He was also and by all means, edit this out because it may sound as though in a way, I’m demeaning. It’s highly sexual. And I’ll say this now knowing that you might edit it out. But he and Billy Daniels were constantly bringing women back to the dressing rooms and all that. And I understand that’ll be, you know, taped nowadays.

Interviewer: Do you think that helped him creatively?

Charles Strouse: Uh, that’s a, that’s a on any level that’s difficult for me to answer. I mean, how men and women negotiate their private lives is is hard for even the person to understand. Sammy was came from a life where he was put upon by the white world. People don’t know that about him. I became intimately connected with Sammy at certain points. We got drunk together and we went to Selma together and there’s a great deal I knew about him. Aside from writing, reading the book, uh, I don’t know. I mean, I. It’s part of his life, part of the needing. I think we all have a measure of it, but he needed to be, uh, given love just about every minute of his existence, Which is funny that he plays the a kind of stooge to Frank and Dean Martin, which is really the opposite of his nature.

Interviewer: Well, speaking of his nature, what was it like working with? A star of Sammy’s magnitude. Well.

Charles Strouse: Working with a star of Sammy’s magnitude was challenging to me. I had worked with stars and I knew that there were certain demands. I was in a it had to do with me to a large extent. I was just coming to a point in my career where I was just starting to gain a little confidence in myself. And Sammy would. Would make my music a part of his life. In put it in more musical terms, he would. He would take notes that I had most carefully thought about, crafted and do jazz. Now I’m a jazz guy. I mean, I grew up in the field, but I felt that, you know, for a Broadway first show that was going to get the kind of attention that this would that I would like him to sing what I had written more or less. Exactly. I know enough about, you know, pop music. I’ve been in the field and we came to grips about that. I just felt that when he was singing Say is a song of of loneliness and aspiration that I had very carefully. And Lee and I should say, had very carefully crafted moments that would be tender and direct. And he had a quality in him which was to entertain people. And on the stage he. Always wanted to be in one, which is the front of the stage, which conflicted with a director that we had at the time who was British and artistic. And Sammy wanted him fired and did get him fired and made me do it. He was he was very bossy and yet had a tremendous inferiority complex, I would say.

Interviewer: Well, let’s go back. When did you first become aware of Sammy?

Charles Strouse: Oh. When did I first become aware of him? I would say I can’t remember a time I wasn’t aware of him. I remember, you know, pictures in my mind of his with him, with his uncle. Or was it his father, the Will Mastin Trio. I was always aware of him. He was just, you know, a great star and was considered the foremost black entertainer, I guess, since Bill Robinson. There was no question about that. He was a wonderful TAPPER, as was Robinson. And and I also knew that he aspired to act more and not be just his character.

Interviewer: When did you first meet him? Under what circumstances?

Charles Strouse: Well, the man who produced Golden Boy was a real producer slash operator, and he did it. Sammy was a prized possession. Commercially and Clifford Odets. Was also and this producer, Hilary Elkins, lied to everybody. He he asked Lee and me if we would do it, which, of course, we would. We weren’t in the position. And then he said to Sammy, when he asked them, he said that Clifford Odets was going to write the musical. And that intrigued Sammy. Of course, Clifford wasn’t, as far as I know, signed at that point. In fact, I wasn’t. I’m not even sure he was aware of it. But this man, HILLARD Elkins, was a real smoothie. And so he convinced that Sammy that Clifford Odets was going to do. We were that kind of the bottom rung of this particular ladder. Yet we were the most eager and I think the first to sign a board.

Interviewer: You certainly were eager because from what I understand, you had to follow Sammy in the wake of his career. Catch as catch can. Yes. So, you know, he’s in Vegas nightclubs. He’s on film sets. Yeah. But tell us what that was like.

Charles Strouse: Well, looking back on it, it was fun. There were a lot of very, uh, dispiriting moments because Clifford was hung up on gambling, among other things, and was also very slow in getting a scene done. We were used to, you know, we came we had written in summer stock. You have a tomorrow on television. You know, we need the scene tomorrow. Clifford was at a point in his career he has undergone very stress and tragedy and political upheavals in his life. And he he gambled. We were in Vegas and we had to have a scene ready for Sammy, and we had a song and all. And as Clifford would, this was a constant scene, I would say with Clifford, he’d say, We’ll have it, I’ll have it tomorrow. And then we would go down because nobody ever sleeps in Las Vegas. And we’d go down at seven in the morning. And there was Clifford who promised us the scene because we had a song that we wanted to fit in or change, and, and he’d be all haggard. And he said, Look, I know, but I’m only $700 behind. I know. And, you know, and this would be at seven in the morning. And it was it was very dispiriting. And yet you could not help but love him. He was he was under the the influence of of terrible elements of faith. You know, he was a gambler. He he had had tremendous failures and great successes. And he was and I guess common parlance over the Hill, he might say, and this this this all had strange. It was it was a very strange background of people. I can talk more about Clifford, actually, than I could about Sammy, because Clifford was very revealing. He was like a child. He used to come in and tell Leon me about his sexual exploits. I mean, you know, I was I forget what I was 28 or something, 30. And I didn’t need to hear this. But, you know, he would tell me who he was doing it with. And a lot of stories about Marilyn Monroe and and Frank Sinatra. You know, he was Frank. I was in Frank’s play and he was very boastful about it and child’s way.

Interviewer: Use that way, too.

Charles Strouse: Oh, well, Sammy was was really big. Yes. I would say, look, hey, we’re all children. But I think they were Sammy and Clifford were more exposed in that way. I certainly understood their needs and their boasting and all that, and I certainly have those emotions. But Clifford was surprisingly childish in a way that you wouldn’t expect. I mean, he was constantly talking about women. He had, you know, nobody does that since high school. And even then, you know, we never mentioned names, but he was always that.

Interviewer: What what was the relationship between Clifford and Samuel?

Charles Strouse: And Sammy wanted to be an actor, which was the reason for his doing this. He. He felt as though his musical credentials, his dancing credentials were all there. And what he wanted was to work in the theater. And we came to grips somewhat about because I certainly understand that. But he his feeling about Clifford was one of reverence. Uh. And it was a it was an odd balance of people, though. They’re both terribly experienced. They came from Mars and Jupiter or someplace. And and yet I think they they really cared about each other in this in in a way that was fun and interesting and a lot of lot of vibrations. I felt more like the outsider. I was the younger and and I should say, and we came from a world I from a very academic musical world, although I’d written in the theater and I was a jazz guy, I could play for Sammy, and we didn’t communicate on that level. I mean, he he liked my playing. Clifford could do no wrong. And it was it was a funny imbalance because Sammy has a way of saying he understood something and he I know. And it was really totally off. Sometimes they were there were problems of communication that were very subtle. For instance, and I know you’re going to cut all this, but it just comes to mind while I’m talking to you that when we first got together and started to have conferences, Sammy, we Sammy would call a meeting and Clifford and Lee and I would go to this meeting where he wanted to give us notes about the show. And he would speak for a half hour. That in words that would seem to connect. And we at the first time he did this, it was a very impressive meeting. He called it in particular. We all got inside, outside. And I remember Lee saying, Did you understand what Sammy said? We came out of this meeting and we said, No, we didn’t understand a word. He said he was talking about the character as we were writing for it, and he would extent rise for maybe 20 minutes, a half hour. So the next time we went in, we decided we should record and then we could play it over again. And so we did his next meeting, which he was very serious about calling these meetings. We went in and we recorded. We told him we were going to put in the tape so we could really and we did. And then he would it would be a half hour. It’s a long tape. And then we would sit and listen to it again and we still didn’t know what he was talking about. And so we finally brought in a stenographer with his permission so we could do it. And the third one, Lee and I and Clifford, we sat there and he was telling us about, you know, the meaning of America and racial balances and things that we knew what he was talking about. And we had it now on record. And we would play it over the through the three of us. It was it was really terribly funny. But it was we didn’t know what he was talking about. We we honestly. So that was a problem. And yet he was conveying something. I still don’t know what, but that was Sammy’s nature. He kind of whelmed, overwhelmed you with the money, connections, the lighting, the the movements.

Interviewer: Well, it sounds like Sammy helped you find the black voice of the character.

Charles Strouse: Sammy indoctrinated us with the world of black experience, which was somewhat true. But I had been among not only black musicians, but being a New Yorker. I had had all kinds of although Sammy told me he was when he was in the Army, and this may be in their book, but I know Sammy told me how the guys all jumped them and six guys all urinated on him. You know, that’s a terrible experience. So he he he carried that around with him to a a and it was always understandable, but it was always very suppressed.

Interviewer: Well, what resulted was. The heart of voice in which is highlighted in Don’t forget, 127th Street resonated throughout the production. So. How is it you came to capture that voice as a composer?

Charles Strouse: Well, how did I capture the Voice of Harlem? I’ve got to say, I did not. I don’t feel that that was a musically success. I didn’t I didn’t have the feeling of what black music was at that point. And I always felt slightly embarrassed when that number went on. And it did well because we had some very good performers and everyone acted black. And but I always felt as though I was I hadn’t caught it, really caught it. And that’s an admission I’ve never made to anyone except my wife, perhaps.

Interviewer: Well, Sammy described bringing the show to Broadway in the process. He described it as the Black Plague.

Charles Strouse: Sammy said he was the Black Plague.

Interviewer: That the process was the Black Plague. What were some of the problems leading up to the opening on Broadway?

Charles Strouse: Well, they fade into into memory. They were certainly rich. The memories, they were experiences. I never had a meetings at the six in the morning, five in the morning, because that’s when Sammy he’d get through the show at maybe three. But then there was always a party. There were always. And if we were to meet and Sammy was very demanding, you know, can we meet after the show? We would wait for hours, literally. And then at the meeting, which was terribly significant, all these gorgeous girls were there, you know, somewhat undressed and it was distracting. And and yet I look back on it with a great sense of that. It was a wonderful time in my life, even though I suffered with Sammy a lot because I think I was innocent of I mean, I knew I’d been around jazz and I’d been around, you know, pretty open society. But Sammy carried with him a lot of baggage. I had just been married the first time I met Sammy. He came up to the house with, I think, six or seven people his age and his drummer, his this this woman who ran his whole life, you know, whereas neckties were at one time he had leave. And agents Barbara and I had just been married. And I remember we had this carpet we had gotten at Bloomingdales, but it was a white carpet from Hindostan or some I don’t know, but we loved it. And that that’s the first remark. And he said, Yeah, I had to have the white carpet. Like, what? What are you trying to do to me? You know, he always went with a bodyguard, too, who is a very nice guy. And the conga player who he insisted on having in the show. And I said, But Sammy. And he was so right because that man lent such excitement to the show, which I never brought to it musically. I mean, this guy would just pick up on it, and it brought a element to the show. And I remember arguing with Sammy about it, and I said, We have 26 others. I want this guy. Sammy said, I want him. And boy, he was right.

Interviewer: Along with Sammy.

Charles Strouse: Fight a lot. Yeah, no, because I kept back but I more am a lot of resentment because he would be changing things so they would become a personal statement of Sammy’s. It basically was a something that’s easy to explain and I should have been more grown up about it. And that is, say, take a song like I Want to Be With You, I Wanna Be with You. I was very proud of that. And it was a very strict phrase, not I will always love you, but I want to be with you. I want to, if you will, you know, have sex with you. And we worked very hard on that. And I used to. I’m just using that as an example. He he constantly sang it with I Wanna Be with You and my trying to negotiate him not doing it that way turned out to be like I was white and I didn’t want it to be that. So I pulled back. I think he pulled back and so I never got close to him. But we acted very close. And at a point, particularly when we went to Selma, I did feel very close to him. And I think ultimately I could say that we we cared about each other, but I went through a bad thing with him.

Interviewer: Speaking of Sam, his love interest, his love interest on stage paralleled his life. He is married to a beautiful white blond by Brit. Was art imitating life.

Charles Strouse: We got to know Mike quite well. My wife Barbara and my. Really became pals. Sweden, as far as I know, is colorblind. I mean, I knew she knew that Sammy was black, but it was a non problem thing. She was a terrific young woman. We spent a lot of time with her, and she even kept it kosher at home for Sammy. It was a weird combination of things. So I always I it was unquestionable that Sammy took his Judaism very seriously. He would not play on the Holy days where I was a total agnostic atheist, actually. And Sammy was very seriously fact. He used to tell funny stories about holding up the shooting on Porgy and Bess with the funniest story he ever told. I’ll never forget it that Samuel Goldwyn, whom he described as a very short man behind a big desk, and they were millions of dollars behind in the shooting of Porgy and Bess. And Sammy came to Goldwyn and said, I can’t play, I can’t do the thing on on Tuesday. It’s Yom Kippur. And Goldwyn, who was losing millions of dollars and simply does it does just a great impression of and I still left just thinking about it that he said Sid, I said to Mr. Goldwyn, he does. He described, you know, he’s short, he’s sitting behind his big desk. He said, he said, Sammy, you know, you’re saying to me, we’re doing the whole thing with the burning of the thing that you can’t. And Sammy said, I’m sorry. So it’s Yom Kippur. And he said, And I still laugh at Sammy doing this. So he said, Goldwyn went, I can’t believe it. And he kept sinking under the desk as he was telling.

Interviewer: It.

Charles Strouse: Telling the story about the little boy who was thinking of $1,000,000 a day saying he can’t shoot because it’s Yom Kippur, which is his holiday. Yeah, well, Sammy told it. It’s just irresistible. But my memory of Sammy telling it and the situation is in inscribed.

Interviewer: The interesting story. Sammy was the only black voice in the creation of Golden Boy. How did the other creators feel about the interracial aspect of the story?

Charles Strouse: How did we feel about from that point of view? I would say totally open. I mean, my.

Interviewer: Setup, my question.

Charles Strouse: The question of whether black and white voices were compatible on the production of Golden Boy never really existed, at least on a on a conscious level, or I even think I’ve been around jazz all my life. And they did in one way. And that is, I think Sammy felt that, that there was something that was enemy about us. I at least I felt it with me because I was trying always to rein him in on, on making a melody that I had crafted. He would kind of do jazz, but an avid jazz guy too. So I understood it. But this was Broadway. And so we we quarreled. But as I say, when we went down to Selma, we became friends.

Interviewer: But it was very bold of doing an interracial love story, interracial musical at the time. What are your thoughts on that? I think the what how did that come to be? What does that.

Charles Strouse: The fact that it was an interracial love story meant nothing to me. I had known young black women in my life.

Interviewer: What did it mean to the audience?

Charles Strouse: Well, we found out when we when we opened it in Philadelphia, we found out what it meant to a white audience because Lee and I got such vicious hate mail that we had to have the police escort us to and from the theater. I’ve never read mail like that. I knew it existed. I read magazines and I didn’t know people like that. But we got the most vicious mail calling us. And how dare we come in and do this? And we I never thought of it as anything, even particularly revolutionary, because I’d been around that world. But it disturbed very deeply the people in Philadelphia where we open. And as I say, I got such threats on my life with terrible language. You.

Interviewer: Well, earlier you told me it was the first time a black man and white woman ever touched on. Can you tell me about that again?

Charles Strouse: Yes. In in looking back on it, though, we were aware of it, too. On a conscious. In a conscious way. But we. As we became more and more aware of it, we we remembered that on television and and in films, a black man and white woman or vice versa, had never really touched they never touched even hands. If Harry Belafonte were on a program and he was singing with Carol BURNETT or something about those two. I know Carol very well. She would she wouldn’t have. But they never touched the even if they would find a hey, baby. I mean, they might have done that, but I don’t even remember that. Never. And we not only had them touch them, we had them do it together with no bones about it. They went down on a couch and the lights went out and played music.

Interviewer: What happened during the previews in Detroit?

Charles Strouse: On Detroit. That was a that was a scary moment, the opening there, because I do remember that I was with my wife and there’s a scene I don’t remember the scene, but a white guy calls Sammy or some other of the characters a bastard. It’s just in the dialog and the black kids. Sammy always had 100 or so kids from, you know, ghetto areas and things like that come to the show. Was very nice was my money. But you know, but I would I certainly agree with them. And at that moment, these kids in the balcony, they were from poor neighborhood. They started throwing things and I said, this is going to turn into a race riot because they started throwing things from the balcony down to the orchestra. And I was sitting in the orchestra and papers for, I don’t know, one, you know, a heavy object that was going to come down. So we dug down. I was in a tuxedo and all that, and I said, Boy, I don’t want to get caught in this. So we left.

Interviewer: So for people who don’t know the show, the significance of a Joe and Lorna getting together, I want to be with you. And so set up what what was at stake between the front lines. Yeah, as you know, people hadn’t seen it. And what was Phyllis and what was actually happening on stage?

Interviewer: Yeah.

Charles Strouse: The original play was a tough fighter, a young kid who was trying to prove himself. But he was a white kid. And his relationship with Lorna, who had been the fiancee of the manager, the man who was running the boxing was in itself threatening enough but that he was a black kid and who finally won on the basis of his physicality, his his freshness, won the heart of this woman. Her name was Lorna. Lorna Moon. That’s very Clifford Odets. He came up with these, but that was the original name that was in itself very problematic in the play because his manager was a sympathetic man, but that he was a black kid now. And we used the same part of Clifford’s play that the plot was the same was an enormous obstacle, particularly in those days, both for Paula, who played the role that she falls in love with a black man. But of course we know today it happens then it not only hadn’t happened really publicly, but never on the stage. Nobody would ever touch on television a black performer and a white performer. They’d say hello and but they didn’t embrace the. I’m aware of that. Not everybody would be so without meaning to. We were groundbreakers and as I mentioned before, got terribly terrible hate, hate mail.

Interviewer: How the audience responded.

Charles Strouse: I think there were no like that. No, I think anyone who went kind of knew beforehand this was part of the play. Also, we were filled. It’s one of the reasons we did such great business. Every night, you know, we ran for three years in New York and closed doing 90% business and then I think two years. And then in London we played for three years because the NAACP and B’nai B’rith bought out houses all the time. The people were interested in it. Which parties went to see Golden Boy was was very significant and funny, really, because the houses were consistently bought out by the NAACP and B’nai B’rith. It was a tremendous interest, his being black and Jewish. And of course the NAACP saw it as a and he was very, very connected. Fact He introduced me twice to Dr. King, Martin Luther King, who I’m it’s self glorifying, I suppose, but who told me how much he liked one song, which has never been well known called No More. And I sent him a copy of it and signed it. And so I was I it still a high point in my life, you know, to have him say.

Interviewer: That the king came to see the.

Charles Strouse: Musical Martin Luther King team came twice to see the musical. And I remember vividly that Sammy invited me up. They were talking in a in a box. And in other words, he didn’t come backstage and he introduced me and I told him how much I admired him, which I did. And he told me how much he particularly liked a song that I say can I can say I have written because Lee wasn’t there when I wrote that song. His wife was ill, so I wrote it by myself. It was a song called No More, which was about us that said I Ain’t Going Down No more, and never became the success I thought it would be. But Dr. King was very complimentary about it.

Interviewer: In that song. The song is called For a Button Down.

Charles Strouse: Oh, no, it’s called No More. I am bound down.

Interviewer: Know who bound to send me live those words?

Charles Strouse: Oh. Huh. You know, that’s probably the most. Did Sammy live the words of Ironbound? It’s very hard to answer because he played too. He played countless roles knowing him as well as I did. And I would say, ultimately, yes, he did play those words, but nevertheless, his personality was such that he he had to make friends with everyone in the room. That included politically speaking, he did. He became a friend of Nixon’s. And I mean, I wasn’t aware of that. He, Sammy, just had to be loved and he wouldn’t let you go until you did. And I have a lot of baby in me, too. And my relation with Sammy was was complex. But I like to think that it became close at the end.

Interviewer: Now read the full subtitle of our documentary is The Many Lives of Sammy Davis Jr. In your opinion, what were some of those lives?

Charles Strouse: Well, taking off from your title, he certainly was a black man and a white man. He wanted to live in both worlds. He he became a Jewish. And I really believe he was convinced about that. No, he certainly wasn’t born Jewish. He was married to a white woman when I knew him, a woman who was Swedish. And they had no. Far as I could see, they had no feeling of color at all and changed religions. And yet there was at heart, I mean, he had gone through much of the black experience. He’d been beaten up as a black man in the services. It’s hard to it’s a tough question to answer from every point of view. Look, I was I was robbed when I was a kid by a black young man. And my son, who was a perfect set up, he was going to a private school with a private school jacket, carried a guitar case. He was assaulted seven times by black kids. And I remember him saying to me, why the why are these ten kids always. Beating up on me. It’s. It was. It was tough. And I think still is. There’s. There’s a measure of, uh. Of of never, never connecting. Or maybe someday we all will.

Interviewer: I don’t know. Well, you know, Sammy, back to Golden Boy. He described it as the best experience of his life.

Charles Strouse: He did?

Interviewer: Yeah.

Charles Strouse: That’s nice. Makes me smile.

Interviewer: Yeah. Do you feel similarly?

Charles Strouse: Was Golden boy one of the best experiences of my life? Because Sammy described that in his way as being one of the best experiences in his life. For me, it was. It was and was not. I. I think I came of age in many ways. He funny. Some of my thoughts just ran away from me. I guess it’s because it’s it’s. It’s too close to the surface. It made me question certain my of my values, which maybe were deeper than I ever realized. But I had a real love hate relationship with Sammy that turned into more love than not. But I also feel that I, who was the most, I thought, friendly person in the world, he made me feel some time as though I was an enemy and I couldn’t quite understand it. I remember that. Bill Gibson noted playwright. I said, Why is it that every time I go into Sammy’s room and I say, You know, tonight, Sammy, you do me a favor if you didn’t that hi. If you’re singing a note above it first and then, you know, instead of the atom, you’re going down. I, I and I said it would be well, he would listen and still do the same thing. And he said to me. Mel Gibson, a very kindly man, said to me, What you should do is not go in and give notes, as you might to a regular actor. But to make do a week and make a whole bunch of notes and then go in. And I know they’re going to bleep this part, but this is true. So that’s what I did. I never did, but I kept notes. And in about a week, I went into a semi and I had a yellow pad with me. And Sammy said, uh, what’s that pad? Man. Oh, something. And I said they were. I said I just took a couple of notes during the thing and I thought maybe I’d give them to Warren. And he said, Get out of here. Which I can understand that I have. And I’m sure that’s not going to get on the. But, you know, here I was this snotty kid. I was younger. But I. I kind of learned a lot from that.

Interviewer: The semi had a lot going on during that time. Sure. He was moonlighting on his own TV series, you know, his first TV series. That was his He made the film. He was recording albums, smoking to pack cigarets a day. Well, reasonable.

Charles Strouse: Sammy was doing everything he could, making a film here and smoking like mad. Never was without a cigaret. He was hardly ever without a drink. Except he said that it was Coca-Cola, but it was a well-known secret that it was always bourbon with it. But I can’t swear to that. But but that’s what everybody said, because he had to have that all the time. They were just not taking on too much to Sammy. That was the only way he had lived, and that was understandable to me. He was in a candy shop which had been denied to him a great deal. And I guess what people do who have been starved in a candy shop is they grab as much candy as they can. Sammy was a good example who had the ability that is the money, the wherewithal to do that.

Interviewer: But the song Give Me Some reflects Sammy’s attitude towards life.

Charles Strouse: The song Gimme Some, which was a very difficult song to write, the style of which because the scene became changed. So he was he was singing the song to a bunch of young kids, to a couple of young kids. And it’s I think it’s a lovely lyric. Beer and whiskey. Whiskey and beer makes you, doesn’t it? Makes your eyes when clear make you lose your money. Make sure that had give me some. And it was it was a and yet it was fun to children. So I always felt that my musical take on it was was a little bit simplistic. I didn’t quite know what tone to take. I think in the hands of another composer, it might have been a more successful song, but it certainly did describe Sammy. He he wanted to suck up the whole world and came pretty close.

Interviewer: Sammy also said, Golden Boy, I occupied 26 hours of his day. Did he overdo it?

Charles Strouse: A Well, I would dispute that, but maybe I’m wrong. I mean, I was not inside his mind, but during the writing of it and even during the performance of it, he managed to get in a pretty rich life. I mean, I think they’re both gone. I don’t know. But I do know that every once in a while, Sammy and Billy, what Billy Williams, what a Billy Daniels might say to me, Look, this is a Delores. Will you stand with her and back? She works for American Airlines or something, you know. But it was obviously some kind of trick. They so I don’t think they were good boys. And I you know, I’ve lived a kind of life myself that I couldn’t say that I was that much different. But they were not they they did pretty good.

Interviewer: Why did he disappear right before the opening? Sammy Yeah.

Charles Strouse: Why did Sammy disappear during the opening? It is the question. I wasn’t aware. I tell you why I. I was too frightened to go to the opening, and I didn’t go because. And I had a pal. A wonderful composer, I’m proud to say, was my pal Harold Arlen and Harold, who was older than I was. But he took a liking to me. And of course, I loved him. And he went as my wife’s date. I just couldn’t. I bet. I bet my children that night, I just there was there was so much so much going on politically between Sammy and the girls and fights and and the show itself, which was a lot of it, went against things that I wanted, went against things that I saw the character as being. And at a certain point, I saw him being a rather beaten down young man who’s whose heart was torn open by these things. It’s a wonderful playing, and Sammy could never get away from that. That nightclub thing he did, which was his genius. He was and he made that character be the other character. But it. I do. I did a lot of growing up myself during that show.

Interviewer: I’d say so, because, you know, in that show, Ray Charles. Malcolm X, Adam Clayton Powell. Dr. King, they’re all heralded, as you mentioned, in the musical.

Charles Strouse: Yeah, I tell you, I’m a New Yorker. I went to public schools in New York. I had friends among whom were black kids. It’s impossible to, I think, in America, not to be aware. Of a person being a different color. To the best of my knowledge. I. Intended it to be a an American musical where everyone kind of got along. It’s just not the truth. They don’t. I was my first job when I first got out of college, was as an accomplice to Butterfly McQueen, the actress. And I was a young kid, but I could get her music in order. She did kind of little dancing and singing, and we played in the Deep South and. I was. I was spat on by white guys. We went to get a hamburger or something and they say you were that woman? I’d say, Yes, There’s this lady with me. We were. We were hungry. And I said, You got to come and back. They wouldn’t even let me in the front entrance. So I’m aware of that. And I’m and I’ve played for a lot of black acts, particularly because I play jazz. I love jazz. And I was one of the few well, I was a white guy. I played jazz and most of the black performers and even the musicians didn’t read music as well, didn’t organize their things. So yeah, I intended it to be, you know, in a world that was framed by a stage and that all of this could happen. And I think it is that blacks and whites would get together and that these two would honestly fall in love. And it seems to be happening. I don’t know. But I would say that Lee Adams and I. Felt that and would have liked it. To be that. And so far, speaking politically doesn’t seem to happen. Although I’m a great admirer of Obama’s, I think he’s one of the greatest presidents we ever had.

Interviewer: What about your trip to Selma? How’d that come about?

Charles Strouse: The trip to Selma came about because Sammy asked me if I would go down with him. Actually, his other musicians wouldn’t do it. They were all scared. And I wasn’t scared at all. I said I’d love to. It was the week or the month in Selma where. Where these two white kids were killed. But it didn’t bother me at all. And we went down. The worst part of it was we were in a small plane. And I’m claustrophobic. And there was a black pilot. It was a black airline. And Sammy kept making jokes about, you know, black people don’t know how to fly our planes. Why are you? He was making all kinds of anti-black jokes. But meanwhile, I was kind of nauseous and all that. And that was the brave part about. Well, there were two brave parts we got there, Sheriff. Bull Connor. I’ll never forget the moment was waiting for us with a gun. He wasn’t pointing at us, but he was standing there with a gun and. Didn’t bother me at all because I just knew. Sure, if Connor was not going to kill me. By the way, it was late at night when we got in and there weren’t any people to greet him. There was just the sheriff. And we went through a fairly empty passenger area. And I do remember that we passed a black guy who was cleaning up a janitor. And I remember this vividly that he said, You. Sammy Davis and Sam, He said, FBI, I’m just imitating him, which I thought was so funny at the time because it was like for us, a very tense situation. And so we went in and and we did it. And it was just I never felt threatened for a moment because I just never did. Uh, and Leonard Bernstein was down there. I remember that. I said he said, What are you doing here? I said, What are you doing here? You know, we were kneeling together. It’s in a scene, actually, in the movie of of of Selma. But I’ve never sat through that movie. I can’t. I just couldn’t get with it. And but I would imagine I’d be in a shot somewhere. And we we prayed with doctor, I think with Dr. King. And I don’t remember he was ever asked to sing.

Interviewer: We’ve assembled all the clips we have of Sammy from Golden Boy, and maybe if you could just sort of talk about what the songs are doing in case we need to set those up. So the first song is Stick Around.

Charles Strouse: Yeah. Of. Speaking of the song, stick around. We tried to capture the thing that the Odette Clifford did so sexually, so successfully in the play. That is, he was a kid who was full of himself and cocky, disguised being actually something else about him and. We tried to encapsulate that in a song called Stick Around. Stick around. You can see some back channels into them. What the boy can do. Stick around. That da da da dee track, Jack. Well, I’m smacking some hack for a night. Can’t remember all these words, unfortunately. But what we tried to do was capture what Clifford had captured. This was a really cocky young kid who on the surface had no had no right to be that he was young, and in this case he was black and it was a white fight manager. And the play develops from there. It’s a wonderful ploy, but I think it’s.

Interviewer: Tell us about the duet. I Want to Be With You.

Charles Strouse: The duet I Want to Be With You was probably it. I think I could speak for Lee in this two of the most important song we had written, really in our lives, because it was a moment in which one had never and still doesn’t happen often. But what had never happened in the American cinema, television or on the stage had ever happened. White. A white woman and a black man did not touch. People don’t remember that. But I remember vividly because we were concerned with it. If if a white entertainer and a black man were on the stage, they talked a lot, very chummy. They never touched. And that was just an established fact. But though most people don’t realize that, we were very aware of it. And so here we were confronted with the fact that they had to shacked up, go to bed together, fall deeply in love, and it had never been done.

Interviewer: So she addressed to me. On me.

Charles Strouse: Oh, sorry. You know, here’s one. It had never been done. And we were deeply aware of it. And the title, which was obviously very sexy. But, you know, we spent a lot of time talking about it. I want to be with you. And they were to not only fall in love, but they were to go to bed together. They would have sexual intercourse. And that was really. So it was, for us, an historical moment, even though I remember it. Somebody else asked me this just the other night. I remember where we wrote it. We wrote it at the Beverly Hills Hotel while we were there filming Bye Bye Birdie, I think. And but it was a very significant moment that I never had full confidence would ever be done.

Interviewer: One of the things and make sure you take the mark I love about don’t forget, on 27th Street Degrees, a musical. Where was it? The Majestic.

Charles Strouse: Yes.

Interviewer: And you’re talking about Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell talked about how hip that song was and how it captured the the the zeitgeist of Harlem and the sixties at the time.

Charles Strouse: In the song 127th Street. I know Lee and I both wanted to capture the zeitgeist of of 100 of that area. We knew something about it. I never felt, musically speaking, that I. I caught the grittiness in the music, but I thought Lee’s lyric was super. I felt that I was being a little bit too. Composer Lee. Not that it’s that much of a tune, but it should have had a kind of street feel, which it did, and it was more musical comedy, and I always felt self-conscious about that. I didn’t feel as much. So in the song No More, where I did try and get a feeling of it being street music. But don’t forget 127th Street. I know they tried very hard, but personally I always felt that it was a it was a kind of not sophisticated, but a little composed for what I was trying to say.

Interviewer: When did. Yes, I can into the score?

Charles Strouse: Uh, well, yes, I yes, I can was a title that of his book, which was written at that time. In fact, the authors were always around us and. Again, I thought it was a super phrase and. I have to say, I felt that musically speaking, I never I never quite caught the the the drive of it. It it sounds to me like it was composed by a guy, but. I don’t consider it a great success musically.

Interviewer: Was it added after the book came out?

Charles Strouse: Yeah, I believe the title. Yes, I can. I’m not sure of this whether we derived it from the book or the book from us, but I think we derive that from the book. Or it was just a coincidence and. It was a phrase that that was. Peculiar to Joe in the in the script that he encapsulated what Clifford wanted to say and what was savvy was about Yes, I Can was very much about the way Sammy was. He really felt that he can do it all. He spent money that way. He gave he he he didn’t give any money to me, but he threw it away on camera as he would often. I went into a camera store with him. He was a big camera bug because he had left those cameras somewhere else and would. Put down $1,000 bill and the camera was $600 and he wouldn’t wait for the change. I mean, that kind of thing. It was it was a profligate. Is that the word? He I think he cared. I guess he cared. I mean, I can’t conceive of people not caring about money. But he acted that way. And indeed, he ended up broke, which was incredible. The man used to make a zillion dollars a week and until broke.

Interviewer: He described Sami as 12 different guys. Uh. In one word, associations. I’m going to throw 12 words at you. Just just give me a quick light. Lightning response. Because it is so important as to how our story flows. Regards to semi prodigy.

Charles Strouse: Wall Street prodigy. He was not a educated prodigy. I don’t know how big his brain would be if they took it out and put it in a jar of alcohol. But he was always on top of every situation. He was not as articulate as he wanted to be. Hoover Hoffer, He was beyond pure. Is that possible? Was he? He threw it all to the audience. He that was where he lived. He loved. He loved the whole thing. And he could. He didn’t improvise as much as it seemed. But it was almost the same thing. He had certain things that were ingrained in his mind. I mean, as a musician, I understand that I can do, you know, food, bigotry, whatever. But that. But on the other hand, I there are certain things that are. I know about that about. So, yes. But he was fearless as far as doing it in front of people and being himself.

Interviewer: Impressionist.

Charles Strouse: Impressionist. Well, he was I the things that I marveled at mostly was that he he had the guts to do it about white people a lot. I don’t know whether he was the best impressionist in the world, but he he was fearless about doing white people. And I love that singer. Well, that’s a personal note with me. He was a wonderful singer, but he kind of messed around with my music. I thought in a way that at the time, you know, I was, I guess 30 or something at the time bothered me because I had really tried to craft notes more than usual, even though I’m a jazz guy at heart.

Interviewer: Survivor.

Charles Strouse: I don’t know. And not personally, but I’ve read about how he was maltreated in the Army. And I can imagine because I grew up in America, we were similar ages, but I knew him as a rich. Successful, extremely famous man. So his survival was an accomplished fact When when I knew him, he was he was a big, big star provocateur. Was he a provocateur? No, he wasn’t. He he actually fought very hard to always he was not a member of the Black Panthers. He was not that kind of a guy. He wanted to be loved and accepted for somebody who was gifted mascot. Well, there I do have a personal interest because I through him, I met Sinatra, whom I got to know quite well later, and Dean Martin and that British guy Peter, or whatever his name was, and this group. And I did say to him that I thought he played the stooge with them a little bit too much. I said, I don’t know why you do that, Sammy. And at the same time, he said to me when I first met them all in a steam room naked with my flat belly, he also said, This is Charlie. He’s my composer. And I said to him later, I said, You know, Sammy, I don’t say, This is Sammy Davis, my actor. I’m not your composer. I was very thin skinned in that time with him.

Interviewer: An actor.

Charles Strouse: After. As an actor. I thought he tried, but he didn’t have the the depth, the sensitivity of a of a fine actor. He was able to submerge his personality enough so he could say the words and convince you that he was in the scene. But he didn’t have the in my opinion, the the subtlety or the loss of of his own ego.

Interviewer: LEGEND Well.

Charles Strouse: Unquestionably, as far as legend is concerned, he was a great legend to everyone. We were attacked by crowds when I was with him.