Speaker When I joined CBS was I think I just finished.

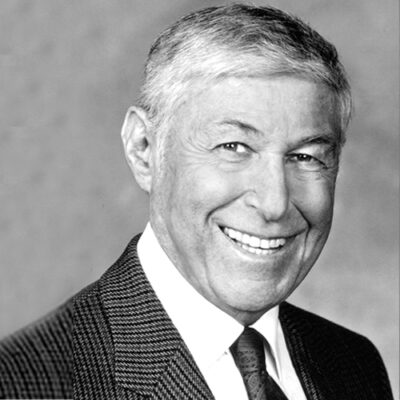

Speaker A season in which they were at the top or near the top of the ratings. And the very first time we posed for pictures, all of us together, Harry. Morally, myself, there are only four of us. And on Mike turned to me and he said, you know, if the show goes in the dumper, they’ll blame you. Welcome to 60 Minutes. Welcome to 60 Minutes from that wonderful man, Mike Wallace. A little pressure. Yeah.

Speaker Yeah.

Speaker Well, I want to sort of make it more conversational and you get rid of that yellow, that yellow things kind of popping a little. That first year, a lot of pressure, did you feel you had something?

Speaker Oh, sure. I mean, I felt I had something to prove because of what 60 Minutes represented. 60 Minutes was at the top that was recognized as not only number one in ratings, but it was a news program that had broken new ground.

Speaker It became news. I mean, if something happened that week, you often saw it or you heard about it because it was on 60 Minutes and there was a lot of pressure.

Speaker So I was the at the time the the youngest correspondent. The only minority correspondent. This was rarefied air. I felt I had a lot to prove. And, you know, there was pressure because it was also something that I had never done before. And I covered hard news. I had done documentaries. I had never been part of a magazine program. And 60 Minutes is a very different animal than an hour documentary.

Speaker What did you know about Don?

Speaker Had you known him, I guess I should ask you, I, I had known Don only since nineteen seventy six my first year covering the conventions, and Don was the producer for the floor correspondents on the floor of the convention. And I guess Kansas City was a Republican convention and New York was a Democratic convention. I was what was called floor relief correspondent, which meant I backed up one of the principal correspondents on the floor. I was backing up Dan Rather at the time, and it was an education for me because I had never seen anyone with that kind of excitement and energy all of the time. Yet at the same time, someone who could be so laser sharp with his focused and what he wanted you to do and what he what it was that he was looking for and able to digest everything that people were throwing at him and make the pitch to the control room about what to get on and have you ready to do it. I just never seen that kind of energy before. I’d never seen that kind of attention to the big picture and to to detail that Don had.

Speaker And I just said, wow. I mean, I had heard about this guy, but I’d never met him. And after even though I wasn’t on the air a lot because Dan was reluctant to come off the floor, uh.

Speaker I was exposed to Don because you hear him in the headset talking to people all the time.

Speaker It was amazing education for me.

Speaker You know, it’s interesting that you that was your first experience with him because he had a reputation as Mr. Television. I mean, I guess in the early days, whenever there was a live event, they call Don You it or you look at you look at all of the old clips of the early days of television.

Speaker You know, for example, the first hook up from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean, I think it was San Francisco to New York. And I think Ed Murrow turns to someone and says, OK, let’s throw the switch. But who’s that? Someone? Don Hewitt. I mean, so I had never met Don before, but certainly by reputation, there was no one who had a bigger reputation for doing everything there was to be done in television journalism than Don Hewitt. Had you heard about his inventions?

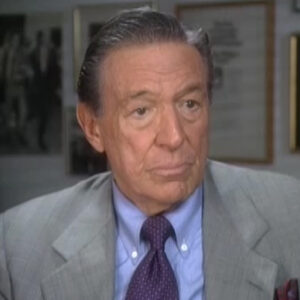

Speaker I had heard the stories over the years of Don trying to invent first what became the teleprompter, I guess. But I think his first effort at inventing a teleprompter was to teach Doug Edwards Braille so that Doug could sit there at the camera and with his fingers, figure out what the words were.

Speaker But I guess his fingers were slower than his mouth because, you know, the thing about Don is that not every idea is a good idea. But the nice thing about Don is that he has that ability to say, OK, I was wrong and to go on. I mean, there are a lot of people who will come up with an idea and they are so involved in that idea and so wedded to that idea and so convinced that they’re right and they have so much ego invested in it that they can’t admit that, you know, I could be wrong. This could be not the greatest idea in the world, Don, is someone who, if the weight of the evidence or the people out there saying, Don, you’re wrong, OK, he moves on to the next thing.

Speaker Yeah, it’s interesting what you said about his attention span. I mean, everyone talks about him having such a short attention span. I mean, it’s really more complex than that, isn’t it?

Speaker I’ve heard people say how short Don’s attention span, as I’ve said, how short his attention span is. I think his attention span is as long as it needs be for whatever the task is at the moment. If he needs more time or you need more time, he is there.

Speaker Generally, he’s able to dismiss it in less time than it takes most people. But I don’t think he has.

Speaker Yes, he does have such a short attention span because I think he’s just in the way he’s able to deal with things, he deals with things easier and quicker than most people I’ve ever met.

Speaker It’s amazing. Did your first you come on 60 Minutes, did Don Kortu I mean, was it Don who called you and said.

Speaker Mr. Bradley, I’d like you to come to 60 Minutes, Don never called me one day Phil Scheffler came downstairs to have a conversation and I had heard these rumors and I had seen Don quoted in newspaper columns saying, well, if there’s a better reporter in this country than Ed Bradley, I’d like to know who he is. Well, that was all well and good, but nobody said, Ed, we want you on the program.

Speaker So, no, Don made no aggressive courting of me.

Speaker I wanted the job I wanted out of Washington while I was out of Washington.

Speaker Then I was here at CBS reports. I was at CBS reports doing documentaries, which was fine for the first year and a half. We did a lot of work and then the second year and a half we did virtually nothing.

Speaker Were you aware of Don’s sort of love affair with the idea of the foreign correspondent?

Speaker The guy in the trench coat, the guy going up, not not until I came to 60 Minutes, I didn’t know Don until I came to tell me about his love affair with that. Well, you know, I think Don is, you know, is a throwback to the days of the guy with the hat and the press card and his hat or the Burberry, the foreign correspondent overseas, that image that that all of us fell in love with.

Speaker And I think Don goes back to the days of the Second World War when he was overseas. He still loves the Queensland.

Speaker I mean, he loves England.

Speaker He’ll go to England and buy suits and you name it, he’ll find the best bargain there and bring it back. But he’s always had if you tell Don, hey, I’ve got a story that looks like we may need to go to Des Moines, he says, go get it. Get I’ll be here when you get back. If you say, Don, I’ve got a story and I think we may have to crash it in London. I’ll meet you over there.

Speaker That’s what everyone said, they said he loves to crash stories and he loves it, loves it now. Yeah, he is an Anglophile. I believe this is a total Anglophile. Um, one second. Just like everyone. Would you let us know when.

Speaker Tell me when you’re ready.

Speaker You obviously had a lot of expectations coming here. What was the reality?

Speaker I didn’t know what to expect coming to 60 Minutes. I knew that, as Don always said, there’s some big tigers in those cages.

Speaker That was my expectation that there would be a lot of competition and that that was something that I would have to deal with.

Speaker And Don and his non managerial way makes it easier for us. Don’s not a manager or maybe I should say, Don, style of managing is you take care of it.

Speaker You guys work it out.

Speaker And you know who’s to say that that’s wrong, I mean, it’s worked all of these years, does he foster the competition, the competitive sort of spirit here?

Speaker I don’t know that he actively does it, but if he proposes something and you’re at all hesitant.

Speaker So maybe Mike would like this and you say, well, wait a minute.

Speaker Yeah, because it does it is it has a lovely competitive atmosphere.

Speaker There is a there’s a lot of competition here. I mean, there’s more competition in this shop at 60 Minutes and there is competition with NBC or ABC.

Speaker I mean, that exists as well.

Speaker But I think that the competition is as Mike and Morley and Leslie. Steve.

Speaker Is it is this happening, I feel I’m so distressed. Let’s see. When you come here. Does Don give a new correspondent any direction, any coaching, any hints, any any anything when you come to 60 Minutes?

Speaker At least when I came to 60 Minutes, Don, in effect said there’s the pool, jump in. I don’t think that Don has ever said this is how you do it. This is the way we like it. What Don does is say, hey, kid, go out and cover your story. And he allows you to do what we each do in our own manner, our own styles and what he brings to the table.

Speaker Is the ability to make everyone’s work better.

Speaker That’s what he is for this broadcast.

Speaker It’s interesting, I mean, you have such a natural ability in front of the camera, you know that I have seen him like I know he started directing Bob Simon and he tends to sometimes help people at the beginning direct them. Did he do that to you?

Speaker I don’t think Don has ever given me any direction on camera.

Speaker Huh? Uh. Not that I recall, I mean, I think Don has has helped me enormously with pieces.

Speaker But on camera, he just lets me be me, and you want to give us an example of how he’s helped you on a piece?

Speaker Oh, Don can take any piece that you bring in to a screen in screening and make it better.

Speaker Than it was when you brought it in. I’ve had pieces where I’ve gone to him and said, look, I’ve done all I can do with this because I need your help now. And he’ll go in and make it better.

Speaker I’ve had pieces that I thought, boy, there’s not a shot in here he’s going to change, not a sound bite. He’s going to move. This is a winner.

Speaker And he’ll go in and he’ll change something and make it better.

Speaker He just has a seat of the pants, instinct and ability to take what he sees on the screen and to change it in its shape in its order.

Speaker And make it more. Understandable to make it clearer and to make it a better report.

Speaker You’re speaking about clarity, the writing of 60 Minutes, I realize that everyone’s got their own style of writing. You clearly have your own voice. But there is something that seems to be a. I suppose there’s an exception to it, but aside from moralise pieces that are sort of ironic wit you for, you know what I mean, some of those pieces, there seems to be a particular style of writing, which is a kind of clarity that each word counts. You might inferring something that’s not true or do you see it that way?

Speaker I think one of the things that Don has always said about this broadcast is that it’s written for the ear. Not the I want you hear. Is what’s important. Yes, the pictures are important, they reinforce what is said and you see someone saying it, so that adds a dimension to it. But you could sit there and close your eyes and listen to 60 Minutes and get the story. You have an added dimension when you see the characters and you get a feel for them. But what is important and what Don is always pushed on this broadcast is that what the guy says is the story.

Speaker Yeah, that’s true, except that there’s a lot of exceptions to that. I mean, I can think of, you know, if you hadn’t seen Quasthoff.

Speaker It would have been a different story, certainly, right, but what he said was important, absolutely no.

Speaker I was trying to say, if I told you the story of Thomas Quasthoff on the radio, it would be a moving story if I told you how big he was and what he looked like and that he was a thalidomide child and that he was now an opera singer. And I heard you let you hear his voice. It would have a tremendous impact. The fact that you could see him is what television is about, which is why television has an impact that radio doesn’t, because you can hear as well as see. But what’s important is also what you hear. And there are too many broadcast today that start with the premise that what’s important is what you see.

Speaker That particular program that you did with, I believe, was produced by John Langley in London, she told us an interesting thing about it, that she had worked for a long time on this particular story in conjunction with you and that. She wasn’t certain that it was going to work out, and she said that she made a deal with you, have lunch with him, and if it didn’t work, you’d be on the Concorde that afternoon.

Speaker We we had. Jeanne Langley had been in touch with Thomas Quasthoff and his people for. Oh, I don’t know.

Speaker Almost a year and he was finally coming to we had planned to do the story earlier in Germany and he had some kind of groin injury and we couldn’t do it.

Speaker He was now doing a concert in London at the Barbican. And we had no idea what he would be willing to talk about. I mean, if he said, look, I don’t want to talk about thalidomide and I don’t want to talk about my physical condition and how I feel about it, we would have had no story. And Jean said, come to London, let’s have lunch with him and we’ll see if he’ll do this. We’ll have to talk him into it.

Speaker And if he doesn’t? You go back home.

Speaker Knowing what was there, the potential, the possibility of what was there and knowing how, I mean, Jean and I have worked together since I came to 60 Minutes. I’ve worked with her longer than any other producer. If she thought there was a good story there, I’d go to the ends of the Earth to do it. So to take a plane to London and spend the day, have lunch with somebody in London and get on a plane and fly back, that night is no big deal. No big deal. So we had lunch and we had a camera crew there and said, hey, this is going very well. What do you would you talk about this thalidomide? And you’re sure? No problem.

Speaker Well, listen, we let’s call the crew and bring the crew in here. And we shot at that lunch. I mean, it was the beginning of the shooting for that story. And it was wonderful. He was there with his mother and Samoan, the associate producer who is German. So we had a language. We had no language barrier there. And it was it was just wonderful.

Speaker You seem to have such a rapport with him. I mean, actually, you seem to have such rapport with almost everyone you interview.

Speaker Not quite honestly.

Speaker I like Thomas Quasthoff.

Speaker He is someone who has struggled, who had a lot to overcome. I mean, you talk about a hurdle. He had a hurdle in his life. He also had a tremendous talent and he didn’t let that hurdle. Diminish that talent. He didn’t let his size diminish that enormous talent that he had and he worked hard. I mean, how many opera singers are there? How many professional singers are there who we hear about? They’re far more that we never hear of.

Speaker And for him to be able to do what he does, given that physical package that he has and all of the emotional hurdles that he has to overcome because of that physical package was just tremendous. I just had I had a lot of admiration for what he had overcome. And I liked him. You know, he was nice. He was adorable.

Speaker We had fun together. You know, we had some food and we drank some wine and we talked it had some more food and some more wine. And it was great. We went for a walk.

Speaker Yeah, it came across. I mean, that that kind of fun of it and the sort of ease of it very much came across. Actually talking about your rapport with people. There was another story that that I want to back up, something I got ahead of myself and we broke and I just I just want to go back for a second or something. So excuse me for of jumping all over the place. The first year you’re here, you’re the new black new guy on the block, so to speak, to Ms.

Speaker I don’t remember. You don’t remember? Oh, I know I won an Emmy for Leno.

Speaker Yeah, I think you got two Emmy nominations. No, two Emmy Awards. Lena and the Belly of the Beast.

Speaker Oh, yeah, Jack.

Speaker Jack, ever did that sort of give you a kind of self-assurance and a different status around here?

Speaker You know, I don’t know if the fact that I won a couple of Emmys gave me any status around. I think what gives you status here is what people see on the air every week.

Speaker I mean, I’ve had years where I had pieces that I knew were Emmy winners. It didn’t even get nominated, you know, and I’m looking at that and saying, what were these judges looking at? This was a winner. And I mean, I’m not someone who pats myself on the back a lot, but there are pieces that you say, hey, boy, this is great, this is fantastic.

Speaker And I never even got a nomination. Do you want to like every piece I did on George Burns piece we did on Paul Simon? I mean, I did the wonderful pieces. Didn’t even get a nomination. I can’t figure it out. I looked at I did a another piece with Ruth Streeter, I just said Ruth put it on the shelf. This is an Emmy didn’t even get nominated.

Speaker What was the Paul Simon piece? Oh, it was terrific piece. I used it in Paul Simon film. Terrific piece. And I know how hard he is to. Oh, tell me about it. There’s a tell me that that’s a good question because I really understand. How hard was that to get Paul Simon to relax that way?

Speaker I don’t know that I would say Paul Simon relaxed.

Speaker Paul Simon talked about some things that he has difficulty talking about. You know, it’s understandable. I mean, you you have part of your life that is private and part of it is public. And most of us or some of us tend to guard those private parts. There are some people talk about anything and everything, but there are some people who are naturally shy and naturally protective. And I think Paul is one of those people and.

Speaker For him to sit down and talk about some of those things that are very private, I thought was a major breakthrough, and we just said to Paul, you know, listen, there’s some things here that we have to talk about. I need to talk to you about your relationship with your father. So know that it’s coming and let’s talk about it, and to his credit, he sucked it up. He was willing to take that step and walk out there on that plank with me and know that I wasn’t going to pull the plug out from under him.

Speaker Are you like that?

Speaker I’m very protective, sure, I know nothing about your personal life. There you go.

Speaker This is about Don, isn’t it? It is about Don. It’s also about 60 Minutes. And Wallace said, don’t tell Don this is really about me.

Speaker But there was a particular thing that. So if I could find that it had to do again with something that Jeanne did and it had to do with talking about your rapport with children.

Speaker She said that your focus that your your. Your ability to interview children and make them feel comfortable is extraordinary, and I’m a kid at heart, you know, I was a school teacher.

Speaker I taught fifth and sixth grade I was trained to sit down with. Kids and relate to kids, and in many ways, kids are easier than adults sometimes. Kids don’t come.

Speaker Someone who’s six, seven, eight, nine years old, doesn’t have the baggage, someone who’s 30 years older, has collected that baggage all of his or her life. So a kid comes to you with a certain.

Speaker With less.

Speaker Then an adult does, and in some ways it’s easier to talk to a kid.

Speaker I remember being and I think we were in the Ukraine and we’re doing a story on this, this kid, Alex.

Speaker And we were taking a break for something, and I think the crew is doing some pickup shots somewhere, and I was just sitting out in the hallway and there are these kids out there and I was just down on the floor playing with these kids. I mean, and it wasn’t something and ended up being shot, but it wasn’t something that was that I was doing to be shot. It was just the crew was taking a break and they were going to shoot somewhere else.

Speaker And I was just passing the time so I could sit there and be bored or I could play with these kids. But it was more fun to play with the kids.

Speaker Do you have children? No, I have been the world’s greatest father. I’m the world’s greatest godfather.

Speaker You know, take care of the God kids you get tired of.

Speaker Send them back at.

Speaker They actually made me sort of think about everyone in this office worked so hard and so long, and I I sometimes wonder if they have any time for any other life or you bet you have to make time for something outside of this if this was all you did. I don’t think you could do it and do it well. I think you have to have some diversion, some other focus, and I think we have each have different ways of pursuing it. We each have different things that we like to do.

Speaker It’s often said, you know, Mike says or Morley says he paints and that’s for his soul. He says Mike doesn’t have any hobbies. But but I think Mike is very social. And I think that’s a hobby for Mike, you know, going to cocktail parties and dinner parties and openings and social events. I think that’s Mike’s hobby.

Speaker What’s yours? You know, I like to ski. I like to travel, um, I love to go to New Orleans. I like music. I like to listen to it. I like to be part of it. You know, I’ve been on stage with some people who have allowed me to bang a tambourine or some other rhythm instrument that as long as I’m looking at the drummer, I can follow the two of the four.

Speaker I don’t have to have much proficiency at doing.

Speaker I was going to ask you about people having a private life here, and I was going to ask you about Dan’s, I think Dan’s hobby is the social life of of this city.

Speaker I think, Don, in many ways is like Mike in that he doesn’t have a he doesn’t play tennis. Mike plays tennis. He doesn’t sail. He doesn’t drive a sports cars as more he does. He doesn’t paint.

Speaker I think Don likes to go out. And I think that’s his hobby. I think that’s what gets him off.

Speaker He enjoys it. I think if if he had, Don would rather go out than stay at home. He would rather go out to a restaurant, to dinner or a dinner party at someone’s house, particularly if it’s an A-list party, then to stay home for a quiet evening. Me, I’d rather stay home for quiet evening. But, you know, that’s what that’s Don’s hobby. That’s that’s what gives him pleasure and enjoyment. And he loves going to there’s an opening. There’s a premiere. You know, there’s an exhibit. There’s a dinner. Don’s going to be there. He loves it.

Speaker Interesting what I want I want to get back to sort of my questions from those who want to sort of think about something particular, there was a time round here when things got actually quite tense, and it was during November of 95 with the Judge Jeffrey Weigand story.

Speaker What did you know about it when it was happening?

Speaker You know, probably not much. I mean, I my recollection is that.

Speaker I don’t know what I knew about it when it was happening.

Speaker Were you aware that something was going on?

Speaker Oh, I think yeah, you know, after it started, I mean, I don’t I don’t think I knew about it before anyone else knew about it. I think when it became generally known, the way things work here is that most of us don’t know what anyone else is doing. I mean, I’m leaving tomorrow for North Carolina. I’m willing to venture that there’s no one here outside of the people, my assistant and the people I’m going to North Carolina with or my team who know I’m going to North Carolina tomorrow and to Washington the next day and to Paris the day after that.

Speaker I’m willing to if you walk down the hall and say, Don, did you know Bradley is going to Paris on Friday? So, yeah. What’s he doing?

Speaker I wouldn’t have a clue. Say the same thing to make up. I don’t know. I looked on the board today and I see Sapers in London. What’s he doing in London? I don’t have a clue what he’s working on a story. We don’t know what each other story.

Speaker When did you kind of discover what went on the air? I mean.

Speaker Oh, no, I you know, there had been some discussion about it by that time.

Speaker It was, you know, it was sort of leaking out in the press and there was some discussion about it. And I think at one point we had we all had a meeting. We had a meeting at my house to talk about something. You did? Yeah. What was it like? It was fine. We just sit around and talk. We wanted to have a session away from the office to, you know, the correspondence, correspondence, Don. I forget who else was there and what was what was it like? It was private. You know, we sat around the living room and and drank Pepsi and Coca-Cola and mineral water and coffee. And we talked about the problems that we had and what we should do about it and how we should go about it and what was decided.

Speaker You know, I’m not trying to be evasive. I really don’t remember what what came out of I mean, what came out of it was that we let me put it this way.

Speaker Did you did you support what Mike and Lowell were doing and going after the story? Sure. Did you support the fact that CBS was not willing to put the story on the air?

Speaker No, I think CBS should have put it on the air. But, you know, I understand their position, but I don’t have to agree with it. I disagreed with it.

Speaker Did you how did you feel about the Charlie Rose show?

Speaker You know, tell you the truth, I didn’t watch it.

Speaker How did you feel when you received this fax in the morning?

Speaker You know, I don’t remember. Yeah. I mean, this wasn’t as big a deal for me. This was sort of between Mike and Morley and between Don and Mike and between CBS and Mike. I wasn’t part of it.

Speaker I was viewing it from afar, but.

Speaker Didn’t the results of something like this impact upon you as a reporter for 60 Minutes? No.

Speaker No impact on me and what I do? None whatsoever.

Speaker You mean to tell me that it wouldn’t impact upon you if you wanted to do a story on a corporation and such a large multi, multi national corporation that might have some ownership in the media that you might not think that my network is my network is not going to support me. I shouldn’t do this.

Speaker No, if I had a story, I’d go after it. And then if that happened, then I deal with it. What had happened?

Speaker But it had absolutely no impact on me whatsoever. It changed my thinking not one iota about how I would approach a story, which story I would approach.

Speaker I if I’m such a contrarian, it would probably make me more likely to look for something to take someone on.

Speaker The reason I say that is because it seems that in talking to a lot of people in the field of journalism, that there was the fallout from that that particular incident was the people felt that now now it’s going to be harder than ever to tackle those big stories. And if you can’t have the support of your network behind you, you know, where do you tell the story?

Speaker You can’t talk about 60 Minutes. Tell it.

Speaker That was and I hope it remains a one time occurrence. It happened once, it had not happened before. It has not happened since, if it became part of a problem, then we would have a problem. As long as it happened once and it doesn’t happen again, we don’t have a problem.

Speaker Did you support Dawn’s decision, what was Dan’s decision?

Speaker Well, he went along with it and went along.

Speaker You know, I don’t remember any discussions with Don. I don’t think I ever talked about it with Don. OK, I’ll go into something more comfortable. I’m. Don’t make me uncomfortable. I just wasn’t involved in it. Right.

Speaker I mean, your impression is that we were all deep in that I wasn’t the impression from everyone I’ve talked I’ve talked to a lot of producers that the atmosphere here was pretty tense and that there was a lot of secrecy, that a lot of people didn’t know what was going on, but there was a lot of falloffs going on anyway.

Speaker OK, I think that’s all office politics. And the nice thing about this place for me is I’m not part of office politics and I tend to stay out of it. Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition.

Speaker I want to talk to you about the Kennedy piece that we followed, you know, quite a bit of it, how that story came about.

Speaker How did the Kennedy story come about? I think Michael Radetzky brought it to me.

Speaker I think, Michael.

Speaker We had been pursuing, I think at one point Joe Kennedy and we were trying to do an interview with him, and when he decided, I think early in the summer to drop out of the race for governor, that sort of put an end to the story. And then we picked it up some months later and said, what about talking now? And I think it grew from that to not just talking to Joe, but talking to as many of the children of Robert and Ethel Kennedy who would talk with us. And Michael Rudovsky went after it and Michael brought it on.

Speaker You mentioned that he thought Joe Kennedy, you know, Joe and I had a relationship and I mean, we talked on the phone and he trusted me. I mean, essentially to say, you know, I’ll be fair with you.

Speaker You know, I don’t have a knife to stick in your back. Everything that I have is coming right here. I’ll sit down in front of you and are questions, you know, I’m going to ask their questions. You know, I have to ask and I will ask them. But there’s nothing that’s coming around with a knife in the back. And I think I think Joe was comfortable and trusted me enough to say, yeah, OK, there may be some tough questions in here, but they’ll be fair.

Speaker And I think I can answer those questions, you know, but I mean, he said to me, look, you could sit there and spend 20 minutes talking about the annulment and that’s what gets on the air. Well, we didn’t talk 20 minutes about the annulment. You know, he asked the question. He answers it. You ask a follow up, maybe a second problem. You go on and we’re not there to to beat up on someone about an annulment. We’re there to get some information about it.

Speaker That is, you know, we started filming just as that story was kind of coming in and and we got involved.

Speaker And following that story, I wanted to talk to you a little about the screening process at 60 Minutes, what it means to everybody, what it represents, and I guess ultimately why there was such resistance for us being there.

Speaker The screening process is different with every piece. I think it depends on. How you feel about the piece, some pieces, you have a lot more confidence than others, some pieces, you know, hey, this is great. Are no problems here. Come in. Take a look at it. There are some pieces that, you know, are problematical that this isn’t working, that this needs help. The point of a screening is every time I sit down and look with the producer, I’m trying to make it a better piece. We will screen it as many times as possible, as many times as necessary until we get to a point where we either say. We’re satisfied with this, let’s show it to Don or, you know, we can’t do anything else with this, let’s show it to Don and let Don help us. And you come to that point.

Speaker And with something as sensitive as the Kennedy piece was, it’s not you’re not sure that you want outsiders in to look at what it is you’re doing when you’re washing your laundry. And that’s what we’re essentially doing. And a piece we’re criticizing the work that you see on the screen. We have people in there who are saying that’s wrong. And no one likes to be publicly criticized, particularly with something that’s generally a private practice and a screening is as private practice. We don’t put screenings on the air. We put pieces on the air. We put the finished product on the air. There are sometimes a dozen, 15, 20 screenings before you get to the final product.

Speaker And yet 60 Minutes and done, I believe, and I think everyone here is very proud of the screening process, the editorial process that the programs go through at 60 Minutes. I think you agree.

Speaker I think that there’s a rigorous screening process. I mean, I get in there with producers and say I want to see why I don’t want you to come in. I’m not not ready for you to see this OK here or come in.

Speaker I want to see where you are now, because it’s it’s our nature, everyone’s nature to show off your best work.

Speaker So if the producer feels, gee, I’m not ready for you to have a look at this, they want to get it in the best possible shape before I see it. I want to see it as early in the process so that I can have more input in it, because I think I can make it a better piece. And then Don will say, hey, what’s happening with that Kennedy piece? Let me see. No, Don, please don’t come in now. I’m not ready to show it to you. We need some more time and need some more work. So I think it’s it’s human nature to say I’m not ready for you to look at it.

Speaker I want to make it better before I show it to you, because I want to show you my best work.

Speaker In this instance, an odd thing happened, or maybe it’s not that odd, but tough talk about what happens when Don gets a hold of a script prior to ever seeing the piece.

Speaker Sometimes it’s a disaster. I mean, you just said, Don, don’t look at the script, but look at this. You got this. Is this guy sincere? Not. And look at it. You know, it’s different when you’re reading it on paper, you know, and sometimes he’s right and sometimes he’s wrong. I’d like Don not to see a script until he sits down to look at the piece with the script in front of it. Then fine, sometimes you go in there and you can be thirty seconds late for a screening, you know, and Don’s and people are still coming. If Don is the first one in there, he’s sitting there going over the script and he’s already making changes.

Speaker You know, you say don’t wait till you see the piece when you look at it.

Speaker But the way maybe this guy here, who is this guy and he can never remember names, he can never remember names, he’ll say if he just confuses names all of the time when when he’s in a screening, he’ll say and and move Jones up there.

Speaker So you mean Smith, whatever, you know, and then thing he calls thing. Yeah. Thing thing is his catch all phrase for everything. You know what the thing and then, you know, just move this down, start with Smith, Will Smith up and and and then when you put the other guy the thing. Right.

Speaker But, you know, you know, he talks a darn talk and you know what he’s saying, you know you know, one thing is because there’s a context for thing and you know what it means.

Speaker Don got hold of the Kennedy script. I think you weren’t here. Right. You were upset, weren’t you?

Speaker Yeah. Because, you know, he’s looking at something and not looking at something. Yeah, he’s looking at paper and he’s not looking at picture and what the guy is saying, you know, and it’s it’s not it’s one thing to hear it and look at it. It’s another thing to read it.

Speaker We he and then he goes down to the editing room.

Speaker If you want to keep him out of the editing room, you don’t want him in the editing room unless you’re in trouble and you need him in the editing room. I mean, you don’t want him in the editing room because you’re trying to make a piece that he’ll look at it and say, hey, gee, that’s great. I don’t want to change a thing. Rarely, if ever happens.

Speaker What was your first screening experience like?

Speaker Do you remember? Yeah, I mean, I had some pretty good screenings early on, I mean, because I did a piece on the IRA, I did the Lena Horne piece was the second piece I had on 60 Minutes that was a winner. And those were pretty good screenings. I’ve had some pretty bad screening. What was your worst screening story? Burma.

Speaker Burma never made air. When the lights went up, there was silence. I said, oh, my God, was it that bad?

Speaker And Don finally said, you know, I’ve never seen a piece I didn’t think I could make better.

Speaker He said, but I’m going to tell you, all you got here is, hey, here comes the monks way. Here come some more monks. Well, they go to the monks. It was a disaster. It was an absolute disaster. Oh, it never made the air. Had you thought you had more than that? I knew I was in trouble. I mean, one, it was a piece I didn’t want to do. It was a producer I didn’t want to do a piece with. I had done a one piece with this producer and I said, I will never work with this person again in life. It was a disaster. So, you know, some people you can work with, some people you shouldn’t work with. I said I shouldn’t work with this guy again, but we went and we did it. And I mean, he’s fighting with the crew. The crew is fighting with him. He doesn’t know what the story is. I don’t know what the story is. Where are we going? What are we doing? All I know is we’re in Burma and there’s no story there. I mean, so we’re trying to do something on the fly to catch this. Catch that and who knows what’s going on.

Speaker You know.

Speaker You know, you don’t know. I mean, I sort of forget about these things that they go on.

Speaker So I guess I mean, it was the question of frame. Was he framed? It was a legal question that. Because of the charges against the former cops and the prosecutors in the case, was he framed? Was there a deliberate conspiracy among these people to cover it up or was it just look, we’ve got this guy, we’ve got somebody, the election’s over. Let’s not rock the boat. So I think it was a matter of looking at this word frame to say, are we accusing them of deliberately framing this guy or are they ignoring the evidence? And as a result of that, he is set up to take the fall.

Speaker You ended up calling it Who Framed, Who Framed. Right?

Speaker Because I think the lawyer said it was fine, that there was no legal problem with saying that.

Speaker I guess what I thought was interesting about it is how careful everyone is in terms of choosing.

Speaker The important thing here, as I said before, is what you hear, what someone says language is important and how you frame something, how you frame questions and what people say on the air is important, more important than the pictures. I mean, the pictures obviously add a dimension. And in some stories, that dimension is bigger than in others. In the case where someone is sitting down just telling you what happened, what they say in the way they say it is what is important. And those are cases where words are important.

Speaker I want to get back in a little bit, Don, Don is, as you know, going to be 75 years old.

Speaker Do you imagine what might happen to 60 Minutes without you?

Speaker I don’t want to think about it. I don’t want to think about this broadcast without Don. I don’t know who would replace him. I don’t know who could replace him. Don Hewitt as an original. There has never been anyone like him. There never will be anyone like him. Someone can replace him. One day someone will replace him.

Speaker He can’t live forever, but they will never be Don Hewitt. What is the quality that makes him so totally.

Speaker If I knew that, I’d find if I knew what made Don unique, I’d find that quality and find someone else and have them ready to replace Don when he decides he’s had enough.

Speaker He just has an innate sense that enables him to take someone else’s work in television journalism and make it better. What is it that Picasso has? How do you describe that? I can, you know, but I can look at a piece and say, wow, that’s great. Don can look at a piece of make it great.

Speaker He took it one day. He saw something he wasn’t happy with. And he was kind of unhappy, said to me, I want to show you something that I adore. You know, what he showed us know like little.

Speaker That’s why they live on a wonderful base, there’s just loads of fun, you know, I mean, I’ve done some wonderful standup hours with pieces to camera.

Speaker We did one in the Roberto Calvi story where we let Blackfriars Bridge in London with ARC Lights at night. And I did this shot walking down under the bridge. It was so dramatic. It was great. I mean, Don showed it in real of highlights at an awards dinner was of course, it had no meaning to anyone because they didn’t know what the story was.

Speaker It’s just me walking down under this dark bridge.

Speaker But it was a wonderful stand up. I did one with Jean in a piece that we did in France and we shot it in a restaurant and I had to do a piece to camera and which I say what it is I’m going to say. And I take the waiters pouring the wine. I take a sip of the wine, I say the trains run on time.

Speaker Well, there was this elaborate shot that starts on the ceiling and it moves down. And I got it right the first time. My forte stand up. I’m known as one take Bradley. We did I don’t know how many takes, but it was that bottle of wine.

Speaker I mean, we just kept doing them over and over and over again because the cameraman didn’t have this right. We didn’t have that right. Well, we try it again. You could do a better reading this time. We went through almost a bottle of wine on that. The stand up in McLibel sitting at that table and ordering, you know, not a French fry or Big Mac inside.

Speaker You know, I think forget it. What it was. I have the venison or something like that, you know, and that single malt scotch. I had a sip of that single malt scotch. I only did two takes in that.

Speaker Maybe three perhaps for that is that it seems like that’s one of Don’s favorite types of stories.

Speaker It’s that story is what Don calls nifty. When Don says it’s nifty, that’s the highest praise.

Speaker What do you think the value of the foreign story is?

Speaker We live in a world in which we are not isolated and we tend to think that we’re isolated because we have an ocean on either side and a big friendly country with which we have no wars to the north or to the south.

Speaker So we don’t have the kind of tension that you have and. France in the 20th century and England.

Speaker And Switzerland and Austria and Czechoslovakia and Poland, we have none of that tension here, and I think we tend to think that we live in a world in which America is the focus of everyone’s world.

Speaker Well, America is not the focus of everyone’s world.

Speaker It’s the focus of our world because that’s where we live. But there are other things out there. There are other people out there. There are other issues out there. There are other stories out there. And it’s important that we should know about some of these things and some of those some of those people.

Speaker And that’s what we do here. We have an opportunity to go and tell those stories. I’m leaving tomorrow for. North Carolina tomorrow, Washington on Thursday in Paris on Friday.

Speaker Great job, great job. Absolutely. There’s a story that you did with microdots ski jumping around, because I know you’re short on time and I know there’s a couple of things I want to cover the Citadel.

Speaker You did the first Citadel story, which was very difficult to do a hard hitting story. And then came the second Citadel story. Did it make it more difficult to do the second story because you were black?

Speaker I know that it made it more difficult. It’s just, you know, it’s more of an issue, but it becomes an issue for other people. I mean, I’ve I’ve been black all my life, so it’s not an issue for me. I am trained professionally to deal with these things. That’s what I do. It’s what I’ve had to do from day one in this business. So I’m sort of used to it. So it’s not a problem for me.

Speaker It’s a very it was an incredibly powerful piece, I mean, to Klux Klan right there.

Speaker But, you know, I’ve interviewed the Klan.

Speaker You know, I did a documentary in 1970, 79, I think blacks in America with all deliberate speed. You know, where I found myself in a town in Mississippi and here’s the Klan out there, you know, so what are we going to do? I guess we have to go talk to them. So that’s what I did. How they treat you? You know, I ask some questions and he gave me some dumb answers.

Speaker I just wondered, I hadn’t thought about it, you were what rarely ever thinks about race around you. I mean, it’s like not an issue at all. And I sometimes thought when I saw a program like that and I wondered if it was something that I do have to deal with every day.

Speaker I mean, because of the country in which we live, because of the world in which we live, where race is an issue, where racism is an issue, where racism is a problem, something you can’t get away from.

Speaker I mean, you listen to all of this talk about, you know, affirmative action. Why should we do this or shouldn’t we you know, people say, well, you know, they’ve done that for 20 years or 30 years or so, not, well, how long was slavery? You know, why don’t we do this for as long as we do? Slavery?

Speaker Before you leave, I have a silly question.

Speaker Where’s my 40 acres and a mule? Hey, you know what a darn thing to be. What a don think of the era. You know, I think the hearing was less of a problem for Don than it was for Andy Rooney and Mike Wallace. You know, I think Don said you want to put a ring in here. OK, I mean, it was it was never a problem for Don. I mean, it was a problem for Wallace.

Speaker And Rooney came shuffling down, you know, and you’re going to wear that thing. Palmer Williams called me and he said that I see an earring and Bradley’s here last week. You know, why do you want to wear that era?

Speaker You know, it was more of a problem for them. Don didn’t have a problem with it, at least not that he expressed to me. What was Mike’s problem?

Speaker You know, Mike’s got 80 years old. I know he says he’s 79. He’s actually eighty one of his ex-wives that he turned it back a year. Why would you turn it back one year?

Speaker Why? Why would you turn it back one year? You know, I don’t know. I mean, I guess maybe Mike’s too old for hearing. You know, if he put a hole in his ear, it might all come to an end.

Speaker Peter Kelm in London said he sometimes throws in distractions for Don in the editing process, things he knows darn well like, I mean, hope of distracting him so that he’ll he’ll get involved in taking out something that, you know, is going to take out and and leave in other things.

Speaker What are your tactics for getting your way with Don?

Speaker You know, I just try to argue with that. I mean, I don’t think Peter Kallum is successful and was successful and distracting, Don, because Don invariably, after he takes those things out, will come back and look at it again, you know, and you say, Don, why are you going to look at this again? You’ve already looked at it. Well, we can make it better. We can make it better, you know, what are you going to say? He’s executive producer. He wants to look at it again. He’ll look at it again. I mean, I think that what you do with Don is say, Don, you’re wrong, you know, and you have an argument and sometimes you win and sometimes you lose. Sometimes you’re right and sometimes you’re wrong. Sometimes he’s right and sometimes he’s wrong. But when he’s wrong, he can admit it, move on.

Speaker He said that one of the advantages and I think that you must take advantage of this, is that he calls London five o’clock in the morning when he can’t sleep. And and he said that inevitably I’ve heard it’s his most mellow moment. I just wondered if you and Jim plotted the night ahead of time.

Speaker You say, OK, Jean, you get him a five a.m. You never know when he’s going to call. No. You never know when he’s going to call. It’s I wish it were that easy.

Speaker It’s not OK. Who’s the toughest interview or story you’ve ever done?

Speaker Oh, I don’t know, Aretha Franklin was incredibly different. Oh, yeah. Because it was difficult for her to bare her soul. I mean, you know, I mean, before we agreed to before she agreed to do it, she said to me, you made Lena Horne cry.

Speaker You’re not going to make me cry.

Speaker You know, I said, I didn’t make Lena Horne cry. I mean, Lena Horne felt comfortable enough to.

Speaker Before we set down, Aretha said you made Lena Horne cry. You’re not going to make me cry, are you? Before she agreed to do the interview and I said, you know, I didn’t make Lena Horne cry, Lena shed a tear because she felt comfortable enough to open herself up and expose her emotions.

Speaker And that’s what we do. We make someone feel comfortable enough to sit down and talk about things that are sometimes difficult to talk about, to show some emotions that you might not want to show in public with all the world watching it on television. And that’s the secret of what we do to try to put someone in that chair and make them feel comfortable enough to talk about it. Aretha had things that she wasn’t comfortable talking about and it was difficult for.

Speaker You happy to be?

Speaker I could have been happier. It wasn’t the greatest piece I’ve done, but it wasn’t something I was embarrassed by. I mean, I think Aretha gave us something else.

Speaker Is there some piece, the nearest and dearest, your heart or you Protestant, that you want to?

Speaker Oh, you know, if if if if I’ve always said that if I got to the Pearly Gates and St. Peter said, what have you done to deserve entry here?

Speaker I would say, do you see my Lena Horne story?

Speaker Downloads that these one of the stories downloads is a Frank Sinatra piece of my first few years here.

Speaker I mean, it seemed like once a month he’d be in there showing that, hey, come on, look at this.

Speaker I was on the floor here with Nancy. I was taking the microphone away. You got to sing. You better sing here. Watch this once a month and show that thing. It was great. It was fun. Why do you think you love the piece so much? Because I think he had a good time doing it. And I think it was good. It was fun to watch. You learn something, you were informed and you were entertained and produce it. What more could you ask for? Exactly, exactly.