Interviewer: I’m interested in personally as an artist process, whether it be a choreographer, a musician, a painter. Do you feel that your process has changed the way you approach your work, not the work itself, the way you approach your work over the years?

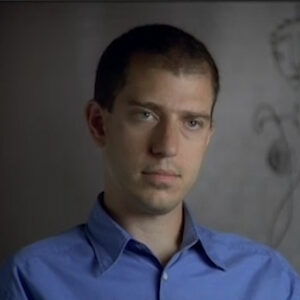

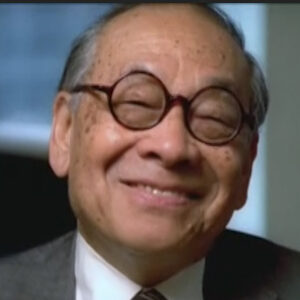

Ellsworth Kelly: I always say that. It started very young for me. Looking backwards, that since my work is really about perception. I can, you know, go back to when I was about ten or twelve. That I was mystified by certain things I saw. And of course, now those visions are like my paintings. But. I was in the army, you know, World War Two, and I had gone to Pratt Institute and right out of high school and it was a commercial art school, and then I was only there year and a half. And then when I got in the army, I realized one night way out and Colorado. In January one cold night, I had a epiphany and said, I don’t want to work for anyone. I want to be an artist myself. And then from then on, it just started. But. How it develops is that I would say to young artists that, you know, they say, how do you do it or whatever. And I say, well, it has to be you will have to want it. I mean, what? That and nothing else, really. And that’s all I feel like I could do. I couldn’t. I used to worry about how I could make it in the world because I’m not I can’t do anything. You know, I mean, I’m not I don’t want to work for anyone. And. Of course, you know, your personal life is one thing, how you deal with life, but. Sandy Calder was a very happy guy. On the outside, and when you knew him, of course, he probably had a lot of his problems, too. But he was. It maybe it was an easier time in the 30s and 40s. Because all the artists that I that I knew in Paris. I went to Paris after the war when I was. Let’s see. Twenty.

Interviewer: Sorry. Microphone.

Ellsworth Kelly: I was saying that was about 25 when I went to Paris and I had been to school in Boston, I was painting from the nude in the morning and drawing from the nude. And when I got to Paris, I liked the I’d been in Paris and the war briefly and I came across Picasso and. Wanted to come back there and the G.I. Bill. allowed that was really a freedom. But as soon as I got there, I realized I wasn’t French, you know, and I wasn’t European. And the whole thing sort of fell apart a bit. And I said, I’ve got to find something. That’s me. And I stopped painting for a short while and went to museums and traveled on my bicycle all over France. And I liked early Romanesque. Sculpture and buildings. And then I started doing things that I saw in nature, say or in architecture shapes that attracted me. And that’s how it all began. And it just has fallen along. And I didn’t meet Calder until the last year. I was you. I was there six years. And I knew the French family, Spriggs Ansary was an archaeologist and he was the father of Delphin. Who I met, the actress, French actress that I met when she was 17 and she met Jack Gunderman and married him and we were very close. And one day at the gym, I go. I think it was. I happened to be walking down and I think I had a date to see Jack or something. And he was sitting there with with Calder. And Jack said, oh, you know. Because he said, oh, Kelly’s doing some very interesting things. I think you should, you know, get to know, you know, see his work as something Jack was pushing because Jack had called it, missed him and Delphin a lot in duffing. And her father, her father and mother had spent the war years in Connecticut for a couple of years. Anyway. Delphin’s father, Oliver, was the only man that bought a picture of mine in France, and then later on I gave him small things when I came back to New York. But anyway, that day. Sitting there next to Calder. I had you know, I was little smart alecky, I guess. And they said something about. What did you get your first ideas for your mobiles? He looked at me and he said. You got to read a lot of books. Young man, you know? And then, of course, you. So then. He also said the jack, he said when you see his painting and he said he said, I’ll see what you can do in 10 years. You know, and that’s really something that, you know, is just like a lot of people are after older artists to see their work and he said, you may be good now, but can your last 10 years. I mean, that’s what it was about. And I said, put me down a little bit. And I thought, oh, boy. You know, that’s that. But then when I came back shortly after that, I came back to New York and he came down to see me. He and Louisa and I had a little room loft on the bottom, of broad street. And I later moved around the corner to County Slept, which I had because you loft there. But he had written letters to Alfred Barr at the Museum of Modern Art and to James Sweeney, the Guggenheim letter, saying, you know, you should look look at his work. And at that time, I guess I’m not sure he had seen any of my work. But he did come down to see me. And here I was in a room about a little bit bigger than this. And all the Paris pictures, which. Who knows about 60 paintings? Which I brought back with me, you know, and. They’re all sort of double hung because I had a high ceiling, but there wasn’t much room there. And when he left. I noticed on the table he had left a fifty dollar check for my rent. You know, and I was shocked, you know. So he invited me up for a party that weekend in up in Roxbury. So I took him a little painting, you know. And it was a painting I thought he’d like because it was one I had done that wasn’t like the single colored panels. But it was one I had done in Paris when I’d lived outside of Paris that summer before, I guess. And I’d been looking up under a tree and there were these big leaves. And I thought I went home and I painted. I thought it looked like Calder’s, shapes, you see all black with little bit of white in between. And he looked out and he said, Oh, you gave me one of the lousy ones. You know, that’s his humor again you know. So I we laughed and said, no, no. I said, I thought you’d like this, you know? And then the next year, I went up for a party and he’s and. He said, you know, your dealer was up here, Betty Parsons, and she couldn’t even recognize that was yours. You really gave me an awful one. But, you know, we had good times at those parties. And Louisa would cook that special stew that she made. I forget the name of it is it’s southern parts of ourselves. Do we all in the kitchen watched her do it and cause a lot of people came and there are only so many bedrooms? I remember I took up a tent and tented right out the front yard. That’s when I guess those years were, you know, when I was really forming. That I remember so pleasantly. And it sort of brings back, you know, the relationship of older artists, how they were, you know, I met Arp and I met Brancusi and. And the CBI in Paris. And they were all such you no easy going gentlemen, in a way they weren’t sort of.

Interviewer: Did you have any conversations about art with him? OK.

Ellsworth Kelly: Not really. But it was just the ambiance. Also, I was very shy and I had never lived in New York and I was very quiet then. And, you know, Jack, younger men and Delphin, we would all go up there. And I remember I met Broyer. And Kim, I tried to see in Paris. I did see Paris when he was doing the ANSTO building and then I. This was several years later and I saw him sitting there at the party and I went up to him and I said, Mr. Boy, I remember I showed you some collages and things like that. And I wanted to. He said, I came here to enjoy myself. You know, that’s that’s very different than, say, what Calder was always sort of friendly and putting his arm around you and making you feel that, you know, it very he was very warm and Louisa, too. And then I remember the artists that he. Took that I met with him like Peter Bloom was there for dinner once. And see, I was always the we were younger than, you know, this was. Well, I was 30, but they were all in their 60s, I guess.

Interviewer: Why did you go to Paris? Why would an artist go to Paris. He went 20 years before you. Yeah. Fifteen years.

Ellsworth Kelly: Well, a lot of the artists did then. That was before the war. And I think a lot of American artists have always gone to Paris. But right after the war, some of us that had been in the European theater saw what they were.

Interviewer: Talk about Calder’s generousity. How did it affect you in your work.

Ellsworth Kelly: Well, when he first returns. I mean, came to New York from Paris and he came down to see me and he had written these letters. I can’t remembering now exactly whether he had written the letters afterwards. But to James John Sweeney, he came down to see me and looked at my paintings. And then I got to know Sweeney and eventually exhibited there. I mean, that was the beginning of my sort of relationship with the Guggenheim. And then I. He also wrote to Alfred Barth, the modern and Alfred Barr sent Dorothy Miller his his right hand. Down and we got along very well and she borrowed five pictures and kept them there several months. And I was always very impatient. So I said I called up and said, you know, if you’re not going to buy them, send them, send them back. So I guess. But, you know, eventually the modern. She did show me in 1959. In the 16 Americans, along with Jasper Johns and Stella and Jack Young woman and I got to know Dorothy then. And that’s why she this was fifty four. Five years later, but she’d always seen my shows. And also he was very generous toward toward his note, to his close friends and things like that. And I and two younger artists, I remember he was going down to Venezuela because he did some sculpture. For an opera house, I think, in Caracas and earlier when Jack and I were in Paris. There was a young man from Caracas who borrowed some pictures of ours. He was a newspaper man and we had an exhibit of that much and had certainly haven’t sold anything. So he we sent pictures and they never came back. And so. We were telling Jack and I were talking to to to Sandy about it. And we said, if you’re. Possible, he said, maybe you can see them in a museum or something. Where are they? So he came back and he had one. I sent three pictures. He came back with one of them. And he said, don’t ask me where I got it. I mean, he was always that way. But I thought that was that was extremely nice. And he you know, he wrote me often.

Interviewer: Can you did when you were in Paris and you came back, your work was undergoing quite a change from time went. Well, six year period. Am I correct.

Ellsworth Kelly: Well, no, I think it started everything started in nineteen forty nine and fifty.

Interviewer: Right. That’s what I mean. Can you talk whether Calder’s work had any influence on you?

Ellsworth Kelly: Well, I always say it was much later that I began thinking about just that, that I think that in one of my shows or one of the catalogs, you know, they always ask you which artists influence you. And I said, well, I said the only artists that have really influenced me. Because I’m a birdwatcher was Audubon, because when I was very young, I was interested in the hard shapes and he’s fantastic artist. Early American Indians. The archaic Indians, because I collect their abstract sculpture and called her because my first sculpture. Then I did the free-standing sculpture in 1959 again. Ah, undoubtedly. I took me. I wasn’t conscious of it, but they really had a basis in his stabiles. I’ve never done a thing sort of dangling. But I’ve always liked the stabiles very much. And then he lived in South Asia, and I regret that somehow or other. I always went to Paris and quickly did what I had to do and leave. But. I remember he came to my openings at the gallery, mark, because he he exhibited there, too, and I remember 1964. He was always joking around and, you know, very amusing way that Mogg himself was kind of a serious guy and. sometimes it was did things that the artists were like, you know, critical of. And so there was a long table, maybe 20 people there on friends and things like that. And Sandy and Louisa, it were there. And Mogg was opposite me, and I was in the center of this long table and we were talking and all of a sudden. Sandy got up behind Mogg so that I couldn’t see him and he went like this, you know. You know, and of course, I broke up. And Mogg was saying, you know, everyone broke up. Yes. So Mark didn’t get the point. But, I mean, that’s something tha his kind of joking around.

Interviewer: Can you imitate him?

Ellsworth Kelly: I need a red shirt and I guess how old was he when he died? Was he’s near 80.

Interviewer: 88.

Ellsworth Kelly: Oh, well, I’m almost a mom. I’m near his age then that when I knew him, you know.

Interviewer: What does a Calder, piece of Calder art do for you you as a view. Can you describe that?

Ellsworth Kelly: Well, you know, I often say that it’s not so much what I like. It’s what I dislike. You know, you sort of say I. I’m like everything really to a certain point. But when you feel some kind of in a family way. He certainly was influenced in by the Europeans in a way. I mean, lived there. And because of the surrealism. His invention, of course, of the moving sculpture is very unique. But I mean, there’s there’s a connection with with Miro and with Mondrian as well, though, Mondrian, and, of course, is very static and very rigid. But the color and form existing, of course, Miro always had this or this touch, it was. And of course, with Calder’s circus and with a lot of his drawings and things like that, they that he brings that into, I mean, the natural part. But is stabiles and mobiles are color and form, color in space, forum in space. And I think that’s when I did my first Gaete sculpture, which was a big X in orange. And I did it over on 60 Street where some of Noguchi was also doing his work. We knew the man who he was a lighting designer and he had this huge factory with and. He allowed us to use tools, and I know Archie and I. I painted it. And then in 59, there wasn’t much painted sculpture. And Noguchi, you always loved stone metal. I mean, my marble mostly, and stone. So why are you painting that? And I said, well. I said, because I just painted some flat X shapes on the canvas. I said, well, I just want to bring the color out into the space, which was really like because a lot of colors were painted orange, I don’t know when he started, most of the things were black when I knew them, but I haven’t studied that much. But there was a funny story about Calder, maybe someone else has told you this story, if not a woman said. I want you to do a Calder. I want you to do a stabile or mobile in gold. Did you stir this? I’ll do it. I think he told me this theory. He said, I’ll do it with what ever material you want. But under the condition that you paint it black. So you never heard that one? So that’s a real Calder story. But I mean, because, you know, the black is very important for you. I mean, the big stabiles course, the mobiles are white and red and many colored, but that form and color in space is what I guess. Nothing. I mean, it’s just like if you come to it and you cause I like Picasso, I like Brock and I like Brancusi very much.

Interviewer: Is it pleasing. Is it invigorating? Is it neutral?

Ellsworth Kelly: What’s that?

Interviewer: Looking at Calder’s work. Well, the other. I mean, why is he successful?

Ellsworth Kelly: Well, it’s about shape. I’m attracted to shape in space. And that’s why I mean, like here, this is a little model that when I was visiting him in Connecticut. You know, of course, this looks like. It could look like a painting that I had done with a black shaped like this and I was immediately attracted to it. See, here’s a white with the black. And this is on a.. This was a study for a sculpture that’s now in Sweden in Stockholm. And this was the first study for it. And it was on a belt. And it’s supposed to move like this with some other things on belts. And I saw recently or, you know, not so recently, but a. A photograph of the finished sculpture. And it’s this, but much wider and changed. But you know, this this is kind of I keep this up in my studio and it just sort of like it makes it our connection. I mean, my connection to him. And I think that, you know, he never, to my face said anything about it. But Jack used to say that, you know, the Calder likes you, likes your work very much in that kind of thing. So that was very nice to hear. But I mean, I think we did have a symbiotic relationship. And Jack, you’ll find out even more so I guess, because he knew about this, a little painting gave me and it signed in the back January 1957. Is it? Yeah. Um, because I. Yeah, 57. Uh.

Interviewer: What were your strongest influences?

Ellsworth Kelly: Well, I think about maybe 20 years ago or so that you’re asked constantly about your influences and of course, I’ve always said because I was an early influence and Beckman because very strong. They’re both very strong expressionist painters. And I was originally very attracted to expressionism, not to geometric painting. But then I said that. The three artists that really influenced me most. I printed this. I mean, this was printed in an essay that it was the archaic American Indians from the mound builders. Two to three thousand years ago, they made sculptures in stone and then little things that no one knows what they’re used for, for ceremonial. And I think those shapes are very American. And they my works in some way resembles them very minimal shapes. And the other was Audubon, because when I was very small, I got interested in colors of birds and the way birds are free spirits. And I love the abstract quality of their colors. Chance almost no red body like a tanager with black wings. You know, it’s fantastic. And Alexander Calder, I said I didn’t feel that I owed anything to the abstract, especially because I was went to. Paris and Boston, where I was painting nudes. In nineteen forty eight and I bypassed New York. And that’s when the heyday of abstract, especially it was, was beginning. So when I came back six years later, everyone said that these panel pictures, which I was doing, the friends were just out of sync with what was going on. And the more I think about it is that it’s Calder. I have attracted to. It was attracted to its work because of shape and color. And being a sculptor, of course. His sculptures exist in literal space. They’re not depicted. And that’s what I think I began doing in Paris, was I didn’t want to depict anything anymore. I wanted to make a painting and panels, which was sculptural and was color and form in space. And finally, in fifty nine, I started doing rather than doing relief’s. I had done a lot of relief’s in Paris. I start doing sculpture. And it was like bringing the color from a shape, color, shape on a painting into our space. And I think that Calder picked up on that from European art, too, because he went quite early and was living there in the 30s and started. And I feel that none no American artist is really picked up on that. And the more I talk about it and think about it now that I feel like I do have a sympathetic feeling from from his work immediately. I didn’t have to even explain it, really. It was just natural.

Interviewer: Tell me about this connection between what you think Calder’s basic shapes in his sculpture to this ancient median?

Ellsworth Kelly: Well, I think that since. These mound builders, they’re called banner stones. And each they’re mostly found in the Midwest. Illinois. Some of them in New York state, Ohio. And each state or each area had its own shapes. And there’s must be about 30, 35, 40 different shapes. And a lot of them are found in in the graves and in fields. The farm is used to find them. When they were plowing. Now they have tractors and, you know, buying them anymore. But they’re the shape is is what I call. It’s not Egyptian. It’s not Near East. It’s not Persian. It’s not Chinese or Japanese in shape. And I noticed that that when Ari used to come from France and visit me and he he saw a painting which was too large a sort of black shaped like a figure eight, which this is when I was doing form on ground paintings in the white part of the corners was almost squeezed out of the painting. And he said, it’s very strange. He said this isn’t. This isn’t because he was an archaeologist that discovered Palmira and he lived in Beirut. Love is there. He said this isn’t Near Eastern, it’s not Egyptian, it’s not Chinese. He said this is very American in shape. And I said, then later when I found these banner stones that looked just like this, you see, it’s always like you’re attracted to shapes that somehow or other. It begins when you’re quite young.

Interviewer: Would you describe Caulder shape as being elemental?

Ellsworth Kelly: Yeah. Well, I guess in in in the mobiles, it’s always about balancing. And it was wonderful to watch him work because he went to the studio. Watched him up in Roxbury there, where it’s almost as if he had it in his head. You know, he would do something and do something else and then do a connection, and he would know exactly the right space. But then he would play with it and then it would sort of develop. I have not looked at the drawings. I haven’t studied those or isn’t accessible. I don’t know how he really worked. But I was watching him work. I felt that it was very instinctive. And. It’s to me, it’s a very American art. But I mean, I always said that about depiction, you know, a lot of painting still is about depicting where there’s just a lot of brush strokes. But when you cut a shape. And you present it in a certain color. I mean, well, you know, it could look like an orange or an apple, but not really, you know, because it’s more. More a shape that exists in space. And there’s something that someone, a critic or writer, something should go into that. I mean,.

Interviewer: So what is what do you think his shapes are about? What do you think his sculptures are about?

Ellsworth Kelly: It’s just a love of shape. That’s all. And I just passed one here on the corner of fifty Seventh and Madison, and I don’t know when they went up. I haven’t been in New York recently and it’s sort of a new orange one. And I said, wow, you know. And then when you walk past it and you look back at it, it’s under. Uh. No. What’s his name? Yeah. But I was thinking, I know the architect is the architect. But I’m forgetting his name, but it’s sort of like it’s all black there. And his orange shape has a beautiful sort of stands out there.

Interviewer: Can you talk if this is a you talk about his inventiveness through his career?

Ellsworth Kelly: Well, he was very playful on nine on one side, like the circus and with his two daughters as they were growing up, I guess he did things for them. And he was very inventive, I remember going into the bathroom and seeing a wooden finger like this for the toilet paper, you know, and I thought at that time, I said, oh, you know, that’s. very suggestive or, you know, and it was just his humor. It was like way, you know. And from the drawings, you can see that I think that the drawings were more playful, say, than the sculptures, sculptures. Very serious. And, you know, when he does a big piece, like in Chicago. Or, you know, that you see a lot of them in Europe, that there’s nothing really like it, you know. And as I said before, that it’s kind of unique. And I think that’s it’s joyous. It’s clear and that’s the words that I want my paintings to be like.

Interviewer: Let’s cut for a second, we have a siren. This is take two and two. Tell us about that piece.

Ellsworth Kelly: This is a small painting that I happen to see hanging in his studio. You know? And I liked it. And, of course, that was before I learned that you shouldn’t say that to an artist because he took it off and said its yours. And I guess maybe he did a lot of small paintings like this. But to me, I always think it’s his smallest little painting. It’s it’s in the back he… I guess there was an X on it. And he used that as a K. And he just said to Kelly in January 57. And I’ve always had it hanging and what I like to about it is that he had this little hanging device, which is a little color. And you can tell its age because there’s no staples, little tacks, which. We all used in those days.

Interviewer: I think we’re going to run out of film. So. How do you think Calder should be remembered? What is his place in 20th century art?

Ellsworth Kelly: He’s he’ll always be a very important figure. And you can see that in the auctions today, that very often after artists dies, they may go into a slight eclipse and then sometimes they don’t ever get back again. But I think he has a very strong foundation. And, you know, from the auction that is the resale of his works is very, very, very high. And that he’s unique in a way. And because of the spirit, very positive, outgoing spirit. I think that there has been some criticism, I think, of a lot of see some of the critics who are more interested in political content or sexual things in the new art are what I feel a lot of the young artists are. They seem to be competing with television and movies and.

Interviewer: What do you think drove Calder? He created 16000 works of art,.

Ellsworth Kelly: Really that much.

Interviewer: It was angst was it? What do you think?

Ellsworth Kelly: It’s just like what you said before, that he’d like to work with his hands. He was an engineer. I think he went over in Jersey to forgot the school. But also he had it in his blood because in Philadelphia, I remember when I went down there once. His father is a sculpture in one of the big circles. And his grandfather has his sculpture there. And then, of course, he has a big one there, too. So it’s like three generations of. I missed that because, you know. I don’t know where it came from. I guess it came from my mother in the way she’s. I was very young she. I have one story to tell that maybe this won’t be used, but, you know, my paintings are about their flat planer. I mean, the sculptures planer, too. And that’s Calders. There may be three dimensional, but their shapes in space. Whereas I may do it just a single shape in space. But when I was about three or four years old or very, very young. We lived in outside of Pittsburgh, and I remember the milk man used to come in the front door and leave a bottle of milk and a pound of butter. And one day, I guess I was just about beginning to walk or something or had walked and I saw this pound of butter, square rectangle of butter. You know. And I stepped on it and flattened it in the rug. And here was this great yellow shape. That was my first painting. And I’ve been flattening everything ever since. But the plainer thing. You know, is he wasn’t interested in bulk. He can make a crab like three dimension say or spider with many limbs. But a lot of the bronze sculptures are heavy and thick. And you have to sort of walk around them. And I’ve never been interested myself in and in, say, mass. I like sort of the image, the flat shape that is somehow in between. What we see in nature and shapes and what we how we think about it. And I want my art to be sort of that. And in a way, I think Calder is. Has that, too. You’re never finished with it. You look at it and you can renew yourself and you never can get to the bottom of it. It’s especially with the mobiles which changed shape and everything that happens is OK.

Interviewer: Do you miss him?

Ellsworth Kelly: Yes, I did, especially when I heard that when he died and I hadn’t and he had been visiting. Jack was visiting there and he said, no, you should come down. And I just thought I had more time and I did.

Interviewer: I guess let’s cut. That’s it. You’re lucky, Laurie.