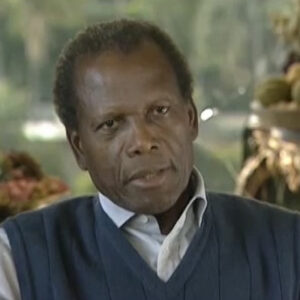

Speaker Cindy wrote, You heard it from where I stood on the margins of the American social reality, the Hollywood of my youth was not a courageous place, nor was it a hostile place for one person as different as a trespasser, traveling too close to separate. Tell me what your position in Hollywood has been and please react this comment as well.

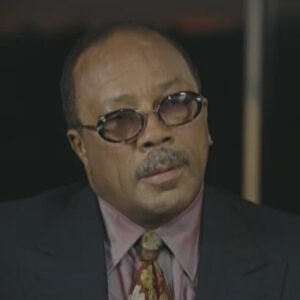

Speaker The comment clearly was accurate, particularly at the time that he conceived that thought. So my particular position has been I started as a story editor and writer in television in New York. CBS came out here again as a story editor and writer, became a producer of a television series like the Virginia and Ironside, then became head of universal television and the doorbell rang.

Speaker New York and Miami, two, New York was very dangerous, very frightening. Hey, tell me about that after we go into it.

Speaker Oh, OK. Something that you know well. He should tell it all, but I think that you have to. Anyway, tell me about what your position was here and in California.

Speaker Let’s see. I became head of universal television and did that for five years and felt, gee, I don’t want to do that the rest of my life. And in the aftermath of what happened at Columbia with David Begelman, I was approached and asked if I would come to Columbia. So I went to Columbia and headed to Columbia for the next six years and then went back and had Universal Pictures after that and then headed Columbia again from 1991. So and now I’m an independent producer.

Speaker So for a month, I hardly so talk about talk about that period when Sunni first came out here and his view of Hollywood as not being a particularly hospitable place. Well, certainly for an African-American, a, you know, great looking, charismatic guy like that, that would have been very, I’m sure, hard to handle.

Speaker What what do you do? Where where are the scripts? Where what’s the audience reaction? You know, all of that, that it had to go on, I’m sure.

Speaker But the fact that Sydney broke through all that and became a, you know, one of the very few major stars of all time, I mean, certainly if the major stars at the time were what is Paul Newman and and what Barbra Streisand and certainly Sydney was as important or more so than any of them. So it’s one has to say, it’s incredible that that happened and told me the result of unique talent, the charisma and I don’t self-knowledge, confidence, whatever it was that allowed him to function.

Speaker It is extraordinary that in white white Hollywood with I mean, terrific people, but they were white people and white crews and white stars and that that this one guy broke through on the level that he did and that white and black audiences alike wanted to see in a more attractive.

Speaker Now, that was was remarkable and I think that, you know, where Hollywood is basically, I think, an open minded community and would want to see good things happen to minorities and and see the right themes done in motion pictures. So there’s that impulse that that exists on the one hand.

Speaker And on the other hand, is that necessity to make money, to make a profit and therefore you’re going to have the greatest intention. But you said, you know, you look at it and you say, well, if we put 20 million into this, is it going to get 20 million back or what hopefully will make, you know, 40 million at least make a profit, because if you don’t make a profit, you won’t be in the job very long. So it’s that tension that that exists that clearly Sidney was able to accomplish what he did make people take bold moves, theoretically. But then they of course, the great thing from Hollywood standpoint is that it worked. It was profitable.

Speaker So.

Speaker What kind of pressure do you think this created for him?

Speaker And do you think that his rise was connected to the civil rights movement of the 50s and 60s?

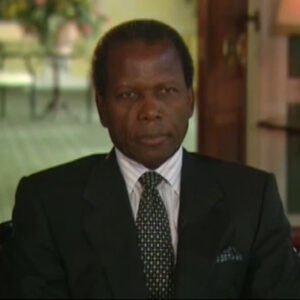

Speaker The pressure, I think, was incredible because there you know, I think any person trying to make a career in the entertainment business movies or that or, you know, whatever it is, theater, movies, that the risks are very high.

Speaker You have to have a substantial ego to say that, you know, I out of these thousands of aspiring talents, actors, and that I will make it, I will persevere. Clearly, most people don’t make it. So you have that that kind of pressure going in. And I’m sure a lot of rational people could have and probably did tell Sidney, you know, don’t get your hopes up. Look at the odds are against you. Maybe you ought to find something as a backup in case this acting thing doesn’t work out. So that normally added to that, I think, is the whole thing that given the fact that he achieved some success in the black community in general, we could look to him as that hope and all the hopes started centering on him. What he did once a reflection was, you know, if he did one kind of picture and not another kind of picture, some people’s hopes were satisfied. Others were dashed. So clearly, he was in in a position to be criticized a great deal. And certainly with the civil rights movement, with all the controversy that was going on, whatever he did was going to be criticized. And I think he chose his way through all of that with great dignity. He managed to achieve things that I think sent incredible messages to to the black community, aspiring talents there. I have hard I don’t think I’ve met a black after that. Hasn’t said to me that he was inspired by Sidney, that he or she that they saw it could be done. And clearly, the the first one through that person always has the most difficult time.

Speaker It’s really crappy to be a role model.

Speaker Oh, I wouldn’t wish that on anyone. So say say that. Repeat what? What is what he said because they’re happy to hear my question.

Speaker Oh, that being a role model.

Speaker Well, I think clearly Sidney Sidney was a role model, and that’s certainly one of the worst things you could wish on anybody, because it’s a crappy thing to have to live up to that you have enough problems being a human being, living with yourself without really, you know, having that burden on you to say everything I do is going to be scrutinized. And clearly you’ll never make everybody happy. So. Right.

Speaker Um, yeah.

Speaker We know that when I was looking for a director on Stir Crazy and we had interest from Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder, but and I was heading Columbia Pictures at that point. So we had to come up with a director that could do the picture.

Speaker And it was a difficult picture to do.

Speaker And it also would need to with Richard Pryor’s approval and Gene Wilder, his approval. So in going through the names of the possibilities of who I was, I think David Triesman was working with me and he had suggested Sidney. And I said, gee, that sounds like a great idea. So we checked him out to see if he was available and sent him a script. And then we met and talked. And it still seemed like a great idea because he liked the script. He had some things he wanted to do to it. But but he was interested and that that went over terrifically with Pryor and Wylder. So that actually worked for me with Sidney.

Speaker That was the beginning of a long, close, good relationship. So.

Speaker Have you seen the other films that he had done?

Speaker Yes, Saturday night talk about the impact that they had in terms of making a decision?

Speaker Well, it was very clear that Sidney knew what he was doing. He could handle humor. And from a studio standpoint, there also was the thing that he had made bids for a price and could bring something in on budget. And, you know, you can get very creative people who can be given the responsibility of directing a picture and don’t know how to make a decision. And that can turn into a disaster that they may have great ideas. But, you know, finally, you’ve got to settle for what you can get in that particular take and move on. And but Sidney, in my judgment, had clearly demonstrated what he could do professionally. And I mean, this was clearly going to be a much larger budget picture, much larger budget picture than any of those. But anyway, it seemed like a very good idea. I didn’t realize how good an idea was until we got the picture made. So I’m telling you guys got a classic. Well, I started realizing a lot of things while the picture was being prepared and of course, while the picture was being shot, because while Richard is certainly the most talented comedian I have ever worked with or seen, that was a difficult period for him. That was the whole freebase thing was just prior to the big action that he had with that. So he had lots of advance, I don’t know, paranoia. There were difficulties with it. He also on location, Sidney had to have incredible patience and that to work with Richard because Richard wasn’t showing up the call. He might make a later call for him and he wouldn’t make the later call. So this was a we all felt it was a terrible thing to be doing to Sidney just personally and also made for, you know, what happens with a schedule when that’s happening where Sidney was terrific, was being able to handle it all. He got the picture. He would make up time. He would figure it out what he could do, how he could accommodate the problems and the quality didn’t suffer at all.

Speaker There were I remember, you know, we had a specific, rather sensitive problem because we were for a good portion of it, shooting in a prison in Arizona and in our society, we, you know, percentages of black prisoners versus white prisoners.

Speaker It’s pretty obvious we were having a shoot inside that prison. And that was that was upsetting to everyone, but very specifically to Richard Pryor. That was not making his sense of injustice or paranoia or whatever go away at all. It was only fueling it.

Speaker So, again, Sidney dealt with all of that and just an incredible fashion, you know.

Speaker The fact that while the seem to have like a really symbiotic relationship.

Speaker Tell you that that was terrific.

Speaker I mean, it was terrific for getting the picture to get the relationship, the symbiotic relationship between OK, of a great aid to putting the picture together and to getting through some very tough situations was that symbiotic relationship between prior and wylder. Many things Richard would just give his proxy to Jean, if that’s all right with James. All right with me, Claire with Jean. So some of that was dependent on mood because at other times we just didn’t enter into the picture and Richard would have bodyguards around. And just I think it was, you know, the drug influence behavior at that point, guns became important and it was touchy.

Speaker So it’s it’s just so amazing.

Speaker Under those conditions, they’d be making a comedy with the grim things that were going on. There was there was a and an incident that got really blown up.

Speaker A member of the crew. We had a mixed group. You know, it was black and white and all.

Speaker But one member of the crew at a certain point, I think was eating watermelon.

Speaker And the reflection of just, Josh, it’s OK.

Speaker There were a number of in just one incident, one member of the area anyway, a member of the crew, I think would serving some snack, which was watermelon, and accidentally the piece of watermelon rind got kicked over to where near where Richard was sitting. And he reacted to it as though this was some racial joke, insult, and it created a massive blow up which which he stormed out of. And the bodyguards were all over. And I think Sydney, you know, finally calmed everything down. I think the crew member apologized and made Richard aware that he you know, there was certainly nothing intended there.

Speaker So little things like that that could get out of hand. That was the worst incident. So. It was a good thing to have seen in a situation like that.

Speaker Oh, the picture I think would would never have turned out, you know, might have not gotten made. I mean, it’s quite possible that it was just blown up in the middle somehow with all the tension it was going. But Sydney was I think he you know, he internalized it all. I think a lot of things were really bothering him. But on the surface, unflappable, just kept moving, dealing with the problems. And I think we all heaved a great sigh of relief when shooting finished snow.

Speaker And then he, you know, he start the editing process, which it’s funny when you see a picture like that, would never have the first idea that, you know, that it wasn’t black.

Speaker Yeah, yeah.

Speaker So, um, and hanky panky with the next project.

Speaker Let me tell you a little more about Stir Crazy just a little bit, because what I really loved about Stir Crazy and I love the fact that it was funny and all that this really demonstrated when we had our SanFrancisco sneak previews.

Speaker We were we had seen the picture in the projection room we kept working on at the rodeo sequence was always too long.

Speaker Sydney kept cutting it and cutting it and cutting it. We kept pulling that down because there wasn’t a lot of humor in the rodeo sequence. It was all well done, but you had to keep cutting it down anyway. We took it out for this snake. First time in front of an audience and.

Speaker From the time that it started, the audience was convulsed with laughter.

Speaker Now what I like about this, I enjoyed the fact there we were we were making a picture about two friends. One was white, one was black. The subject of race does not come up in the picture. There it is just two bodies. It’s two bodies like and I I’ve always loved Laurel and Hardy. So, you know, it was Laurel and Hardy and, you know, you love you love the two guys. So and in San Francisco with this test audience, it was evenly split, black and white. And I felt at the time, this picture is doing a lot unsaid in the whole area of race relations because it was saying a difference. And, you know, people are people and we the audience is that night I felt that we were going to have to put subtitles on the screen so that people could hear the dialogue because they were laughing so hard they were missing some of the best jokes. So which, of course, people that didn’t want to see it again immediately because they felt they had, you know, missed things. But and we were able then after the screen, it was very clear we had a huge hit and we were sitting and I went and got on the phone. Richard was in Hawaii and we called him to say fabulous big hair. Laughter All that. He was very mild and almost disbelieving. But I think he was also enjoying what he was hearing. He just wasn’t going to react too much to it. And we called Jeanne. So anyway, that that was one of the more triumphant evenings I’ve ever had.

Speaker And still remain and enjoy to this day. It’s absolutely a classic comic.

Speaker Yeah, it is I think it annoyed me critics weren’t buying it at the time, they didn’t see how good it was. I think many of them have come more lately to the game. But but there was no question it was such a huge hit.

Speaker It was the thing I remember coming out of that, that there was a blizzard in Michigan, in Detroit, and there was a drive in that was turning in record numbers for stir crazy. And we were saying, how is this happening? Because they were just constantly sold out. We know a blizzard was there and we thought, you know, maybe all the cars are trapped and they just keep charging them for each other.

Speaker So what do you think the answer was? If it’s a hit, people go to it.

Speaker So talk about hanky panky and the follow up to stir crazy.

Speaker Well, given our great success with Stir Crazy, I really wanted to do a sequel and tried very hard. I got, you know, Bruce Jay Friedman to come up with new material. And I worked on Richard worked on Gene.

Speaker And Richard’s consistent attitude was talk to Gene. Whatever Gene agrees to, I’ll do.

Speaker So Gene found none of that material up to his standards.

Speaker So we, uh, sort of gave up on that. But in the meantime, we had a script that became Hanky-Panky, and I talked to Gene about that. And he was interested.

Speaker We talked about casting director and, you know, easy for us to agree on, Sidney, and it certainly would be the right director for it. For the real thing was the meeting woman. And that was not so easy because I was thinking of it more comedically at one point had I think I was having lunch with, you know, breakfast with Gene at my house.

Speaker And I said, what about Dolly Parton?

Speaker I thought I was going to go through the roof, that he felt that would be cartoonish and he wanted, you know, leading woman.

Speaker And, um, anyway, um.

Speaker Then I mentioned Gilda Radner and I found interesting, so because I was explaining that we can’t have just a straight leading woman is a comedy, and Gene had a tendency to think of himself more as Cary Grant and forget the broader side of what he could do.

Speaker So he wasn’t somebody appropriate for Kerry.

Speaker So but he agreed to Gilda.

Speaker Sidney was terrific with that. We put the whole thing together and we all thought we were going to have this terrific comedy and something was wrong.

Speaker When I started seeing the dailies and I was talking to Sidney and he was doing interesting stuff, but I started getting a little nervous. I wasn’t seeing a lot of humor.

Speaker And I talked to Sidney.

Speaker He was getting what he could. And about halfway through the picture where I was saying something, sure, I had dinner with Gene and he explained how old Gene and Gilda and I were talking about this great romance that had came between, you know, that that had occurred between him and Gilda had said she walked on the set the first day, took one look at Gene and fell in love with him and that that had influenced how she was approaching the role, the raucous, funny, loud, you know, every comedian disappeared and she became the leading lady and more quiet because she explained to me that she realized Gene was agreeing with her.

Speaker She realized that she didn’t.

Speaker Gene was being so funny that she didn’t have to do that, that he could do all that. So I realized that playing at it, you know, our problems anyway. But Sidney was doing a good job. It was kind of there was no way to change this, you know, without some phlebotomy or something. So we cut the picture together. A, you know, it was well done, but it was more a romantic suspense thriller than the comedy that we really set out to make. So it was strictly because Gilda fell in love with Gene. And, you know, how do you, like, insure against that sort of thing happen?

Speaker You can’t just need to hire somebody who you hate and she’ll compete.

Speaker Oh, right. Right. Um.

Speaker Siri makes everything look so effortless, yes, you know, many people didn’t think that he had to struggle, talk about Sydney as an artist, how he can fly his craft, his discipline, his passion.

Speaker Well, I mean, when one talks about struggle and I’ve had long conversations with Sydney on this because he came from a very poor background, I came from a depression, poor background.

Speaker So there were some shared experiences. I lived in the south in a region of Tennessee when I was in the ninth grade, and this was before civil rights were heard of. And I was a damn Yankee and was nearly killed there because we’ve moved there from California. And I was called all sorts of names and it was a very tough area.

Speaker The people dropped out of school at 16, and since that area was a dry county for liquor, these kids could go to work for the bootleggers. They would drive illegal whiskey in from North Carolina. And these kids carried guns and they were dangerous. So and I was the target of some of their younger brother’s hatred. So and one night I was taken out and nearly killed. So I got an idea of that. That was around the time of the year. No, it wasn’t a time. Ultimately, if you remember the Emmett Till case, I could identify so much when that came along because I’d spent an evening like that with some of these small town bigots that felt I was a [Unrecognized] lover. And I you know, I was all sorts of evil things. And and they had me out in a dark country road one night and they were slapping me around with tire irons and a lead pipe. So anyway, that particular background led me to really understand some of what Sydney went through and his trip from Florida to New York and when he left the Bahamas.

Speaker And here is this kid with a Bahamian exit poll numbers continue and I will start again. You said from NASA to Miami.

Speaker Oh, yeah. Ah, we’re rolling it out of the story of when Sydney left, NASA went to Miami and then from there went on up to New York. That’s an incredible and dangerous trip he was on. Here’s this kid with a behind Bahamian accent, which is musical but not easily understood. The air has to get used to it. Who was in the Deep South long before the civil rights movement had made any impact. And he was really lucky that he wasn’t killed. He had told me about one incident that where he was nearly killed by people that just didn’t like him being where he was, didn’t like the color of his skin. So he was fortunate to get out of there. But now the whole thing of going to New York and with no money having to survive, taking any awful job, you know, dishwashing, whatever, and then having the will to change mean become an actor, change that accent, because those are tough things to get rid of.

Speaker And, uh, I had no professional help in doing that.

Speaker We talked about how he he did it and he did it listening to the radio, which again, it’s, you know, the triumph of will if they act. I think he was motivated because I think he tried out for the what was a Negro Ensemble Theater. And they laughed at him, so because of the accent, so he was motivated to change and did so, that was remarkable.

Speaker He reversed himself. Yeah.

Speaker A a recreation that, uh, uh, how many people can do that? So, so many would say, well, you know, I have this accent. That’s my accent. It’s all I can do. So I find, you know, I’ll go dance or whatever.

Speaker So.

Speaker It’s a remarkable journey, criticism thrown at Sydney in the late 60s and early 70s. Were you aware of that vicious Clifford Mason article that was in The New York Times?

Speaker The title was White. White folks love Sidney Poitier. So where do you think that that kind of backlash?

Speaker But that kind of terror attack.

Speaker Well, I think it but let’s face it, with the unique kind of success that Sydney achieved.

Speaker That had to bring out all kinds of conflicting feelings in the African-American population. Certainly pride has got to be part of that. But as human beings, we’re never far away from a simple thing called envy. And, you know, he can do that. What about me? So there’s always that feeling floating. I think, you know, clearly with what was going on with race relations in the United States, people could expect him to work miracles, to do things that he’d never be able to accomplish, that if he took certain positions or whatever, he might ruin his career and accomplish nothing. So I think certainly by doing what he did was a remarkable symbol and did more than, you know, had had he become ultra militant. But, you know, you’re always going to have the critics that say, you know, do it my way. Your way isn’t isn’t as good as what I would tell you to do. So so, again, I think it’s understandable. You know, we have this problem of the fact that since 16, 19, one part of the population has been enslaved and we’ve dealt with the first few hundred years of that. I think dealing with the ongoing residue of that. You know, it’s the great agenda. Certainly, you know, I’ve I found that a an important theme in motion pictures to keep returning to. How do we how do we solve the problem of races living together? How do we solve that problem of the heritage of slavery and what it did and hatred?

Speaker Yes. Oh, yeah.

Speaker I’m looking at it. I, I think I was struck by my experience in Tennessee that it’s always been something I’ve been very aware of because I found when I got on me when I first moved to Knoxville and got on the bus and found that a certain group of human beings were supposed to where it had to be the back of the bus. And I think I was 13 years old and I’d come from Glendale out here. So it was like that. So I didn’t know how to cope with it. It was embarrassing. It, you know, I couldn’t stand the fact that other human beings were treated that way.

Speaker But as I said, when we have done the society has done a lot to change that.

Speaker But clearly the scars and, you know, open wounds of that remain that you can’t just wave a wand and say, uh, but several hundred year period is now going.

Speaker It will leave a residue of, uh, problems, difficultly, hatreds. And I think of how do you how do you solve it? Uh. I think, uh, you know, we have that the two things I’m always drawn to. One is race.

Speaker And the other the other is, is the other problem we’ve had, which is gender. And those themes, I think with race, I felt stir crazy, did something there. But but I think it’s given me an interest in things like Soldier Story, which we did at Columbia, or Cry Freedom, which is the other another attempt or Boyz n the Hood, which I had at Columbia Soul Exploration and.

Speaker And I do think we make we make progress and certainly too slowly, but I mean, the great thing is somebody like Sydney did so much, I think just by being there, by being the star, being the exception, being the giant, because it was very difficult for anybody in the society to really say, oh, I don’t like him. You know, he was appealing. He’s smart, he’s great. I’m not a comic, not, you know, nothing in that category.

Speaker It’s leading man and and a tremendous personality.

Speaker What I think from today’s perspective.

Speaker Um. That’s Sydney’s legacy. Maybe the legacy is in Robert Townsend.

Speaker Well, I think it is. I think if you were to look around the community, what’s happened to Hollywood and say a lot of this is due to Sidney, someone who was at the I’ve done Tuskegee Airmen for HBO that Laurence Fishburne starred in, and he was not the one to talk about Sidney’s role in influencing him.

Speaker It led him to believe he could do something like that.

Speaker So.

Speaker And I’ve just heard that from from so many Cuba Gooding that we had in boys and, uh, and I had he was also in Tuskegee Airman.

Speaker So he broke open.

Speaker He broke through and did it in a very dignified way. I mean, it wasn’t he wasn’t the novelty act, he was the mainstream star.

Speaker And I think that’s what counts for so much.

Speaker Um, has Hollywood changed since those days that he mentions, is there?

Speaker I don’t know whether there’s more courage and consciousness.

Speaker There’s just a lot more African-American entrepreneurs. Um.

Speaker Well, I think that’s that’s been the the great thing to.

Speaker You know, from an economic standpoint, you face some fairly simple numbers when when you think about investing money in the motion picture of most of your audience out there in the United States is white.

Speaker And I think what the African-American percentage of population is 12 percent. I think they’re disproportionately heavy movie goers. So they represent more than that 12 percent. But still, for that mainstream hit profitable picture you need you tend to need the white audience. I think with Boyz n the Hood, we got probably the top number that you could get with so far with a picture that was aimed, you know, all about an inner city black problem, a story like a family story like that. We did, I think. Fifty eight million dollars with it. Which big number? As long as, you know, your negative cost is as right as ours was there. But I think the industry experiment’s a little. But that is my real point actually, about Spike Lee, because I think Spike. And you know, some of the others, but I think Spike was the first one to really do it where he made a picture, he didn’t go to a studio. He raised the money. He made it for very little. What was it? She’s got to have it. I think that was an incredible breakthrough. But I had spoken the language that this business understands. You know, it was made for very little money and it was very profitable. And at that point, anybody will sit up and pay attention and say, well, there’s there’s clearly a business there. We better pay attention to that. So so I think that that was the the huge breakthrough, because I don’t I’m sure he couldn’t get anybody to finance that kind of picture. You know, I had found when we did things, I learned a certain amount from my approaches to certain things. We’re dealing with African-Americans or blacks in the world in that. And that was with the picture like Soldier’s Story, which Norman Gerson directed, was made for the right price of made for like eight and a half million dollars. We did enough money to make a profit. I think finally the film rental is about 12 million or so. And I saw we drew the white liberal audience and the middle class black audience. We did. There was no huge upside there. In a sense. That same thing happened on a glory that they did bigger numbers, but they they were still getting the white liberal audience and the middle class black audience. I had seen that audience in stir crazy. And I was saying, where’s that audience? Where’s that young, hip black audience not coming to these other pictures. So, you know, they may be going to Arnold Schwarzenegger or, you know, they’re doing something.

Speaker But I think that’s that’s one of the reasons that I ultimately got involved in making Boyz n the Hood, because it did get that audience. They turned out that’s why the numbers were big.

Speaker It’s also a great thing that yeah, that was John Singleton just had a brilliant conception. I wrote that script and did a great job in directing it. And I congratulate you.

Speaker Oh, well, I was so thrilled to have been able to be part of it, you know, to get that, because better when I read the script, if it had struck me that I hadn’t been moved in that particular way since I had seen The Bicycle Thief. And that’s part of why I was intrigued, because I thought, gee, if I could identify with an Italian family, you know, they don’t speak English and that why couldn’t all white America identify with this family in the inner city of L.A.? So and quite a few did.

Speaker So I got a big audience there, but none of this would have been happening without Sidney.

Speaker Uh, I mean, we can look at that picture and say, all right, just back up who led the way, who said, uh, that somebody who was black in the United States could do this.

Speaker Uh, and the only one would sit that way back in Raisin in the Sun. Yeah. Oh, yeah. Yeah, right. That’s all I have for you.

Speaker Well, this is bad. You make such fun.