Speaker In remarkably, a very small number of shows has left a big imprint on the American musical and what we now realize was its last great heyday indeed when he left the musical theater for all intents and purposes with Fiddler on the Roof in 1964. We now realize that was sort of the end of that kind of storytelling musical in the tradition of Rodgers and Hammerstein and their peers. Interestingly, Robin sort of did his apprentice work with Rodgers and Hammerstein, the king and I. But gradually that was in 1951. Gradually throughout the 1950s and into the early 60s, he perfected techniques that were starting when he entered the theater of making musical theater storytelling completely seamless, taking the idea that you don’t just stop to do a song. You take the script, the scenery and the lighting, the performances, the music, the lyrics, all of it, and make it into one integrated whole so that it’s almost cinematic in a way. And other people had certainly experimented with these techniques, including Agnes Dumbell, who who worked with Rodgers and Hammerstein on their breakthrough show, Oklahoma, and also Allegro, which may have been the first show which ever had a director and choreographer in the same person. Dumbell. It was a flop. The gopher on that show was the young Stephen Sondheim. All these things sort of ultimately would connect, but Robbins took it a step further. And because he had the ability both to direct actors to understand material and the deepest meaning of material, including, most importantly, its theme and of course, was a choreographer, he had all the abilities needed to take the step forward for the musical. And you see it in West Side Story, Gypsy in Fiddler on the Roof. And then he was gone.

Speaker Do you see him as a sort of bridge to different era, sort of, you know what I mean, spanning?

Speaker Well, interestingly, Robbins, when Robin’s left, his immediate successor was Harold Prince, who heretofore had only been a producer. And in fact, he was a producer of West Side Story, the breakthrough Robin Show. And he was the producer of the last Robin’s musical Fiddler on the Roof. Right after that, when it became clear that Robbins was not going to return to Broadway, Prince started to direct. And ultimately, only two years after Fiddler would direct another breakthrough show, Cabaret, the original production of Kander and Cabaret, which use robbins’ techniques to a fare thee well. However, Prince was not a choreographer, so when he did his sort of robbins’ like musicals, he he was reliant on other choreographers, ultimately finding Michael Bennett, with whom he would do with Steve Sondheim Company and Follies. And that would lead to Bennett branching off and doing a chorus line in Dreamgirls and becoming sort of the ultimate expression of the robbins’ genealogy, if you will.

Speaker So how was the musical different then as a result of him having made his mark on it?

Speaker The musical is different in several ways. First of all. In storytelling, it’s just much it moves much faster. You don’t, as in the old days, even in the more advanced Rodgers and Hammerstein shows, you don’t have the action come to a halt. So two people can have a scene in front of a curtain while they change the scenery and scenery. Changes basically happen in full view of the audience consistently. It just kept whirling and whirling. You look at something like West Side Story as it moves from the dress shop to the next dance to take things out of sequence. But you know the quintet for tonight where all the jets and the sharks and the young lovers are all going in different directions and it’s all visible to the audience’s eyes. Think of that next to the old fashioned musical where just two characters are there at a time settling their business. Then there’s a big production number. Then you come back to the subplot characters and so on. That’s revolutionary. Robins didn’t do it all alone, but he was the one who who perfected it, took the dumbell ideas of using dance to tell the story and took them even further. The other thing that he did in collaboration with the artists, the writers he worked with, for instance, Bock and Harnick, the songwriters, also Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim, obviously, and Arthur Laurents, the book writer. He mined deeper themes and material. He looked for deep, deeper themes. And so while there was a history of musicals with serious themes as part of Broadway’s history going back to Showboat, he kept that flame alive or sort of reawakened it. And so West Side Story really was as much a social statement about what was going on in youth in America in 1957 as it was that specific resetting of Romeo and Juliet. And in the context of the time, you have to understand that most Broadway musicals were still extremely frothy. It was still the Broadway of the music man. Bells are ringing. Happy hunting, my fair lady. Not to knock these shows. Some of them are quite good, but there was no Blackboard Jungle kind of gritty use of the musical theater at all. It never even occurred to anyone, despite there being the history of shows like, say, Porgy and Bess 20 years earlier. And so that was a quite a shocking thing. And indeed, it got a mixed response from critics and audiences West Side Story and didn’t win the major awards, lost the major awards to the Music Man.

Speaker Fiddler on the Roof was a show that threw a coincidence, I watched a lot of the development because I had a childhood friend whose father was one of the authors. And so in my early teens, I saw what Robbins’ I saw Fiddler before Robbins came in, when they were still developing the script in the songs and after he came in. And there could be no more clear cut example of what Robin’s grasp of material was then the addition of the song tradition. When Fiddler was in Bakker’s auditions and they were raising the money, it began with a song that no longer exists in the show called We’ve Never Missed a Sabbath Yet, and it didn’t have those big things had basically the same plot, had the shallow Millicom characters.

Speaker But Robbins had this idea of this bigger theme that will announce itself at the at the beginning of the show and would give it a greater emotional weight, historical weight. And I think a universality that took a show that a lot of people in the theatre industry thought to Jewish will never have a mass following and so on before it opened and turned it into this institution that exists to this day.

Speaker You wrote that Jerry Robbins defined the way our country pictures itself. Can you talk about that? What was American about?

Speaker When do I say that I’m a fighter?

Speaker But from what I’ve seen in your his obituary, define the way our country pictures itself and I think you used the three sailors and fancy free. Well, yes, OK.

Speaker In in some in his best work or his most enduring work, there’s no question that Robbins created images that have now sort of passed into Americana. Certainly the three sailors that he choreographed, both in the musical on the town, but before it the the ballet fancy free, which sort of put him in, and Leonard Bernstein on the map before it was a musical that that image of of three sailors on shore leave in New York at wartime persists. Now, many years later, people know that image as much as they know something like the flag, even if they don’t know where it came from. It’s not like everyone knows what fancy free are on the town is. It’s just past into the language. And it was a visual image that Robins created with on three dancers independent of the material, independent, what they were singing or what the music was. I think that even though some people would say, including me, that the whole idea of gang warfare in West Side Story, the Jets and the Sharks seems a little tidy by contemporary standards, even by the standards of the time, it’s sort of a sweetened version of it. Yet somehow those gangs squaring off in the that Robins choreographed remains a statement of what we think of gang warfare among teenagers being even if it’s actually changed in reality a lot. And interestingly, too, in the movie of West Side Story, which was largely filmed in New York, but in an area that was just about to be cleared for Lincoln Center on the West Side, he sort of made that kind of tenement, New York, New York and the urban America that would explode several years later, the 1960s. He sort of made that part of our consciousness because we think of that movie and we think of those knife fights and what was going on in the movie of West Side Story, which is how most people know West Side Story. So in that sense, I think that he’s he’s played a role in sort of classic American art.

Speaker You also talked about ways in which his career encompassed high and low culture, and I wonder if you can talk a little bit about that, because he’s somebody who operated in several arenas and combined those things and how much that kind of duality reflected the time in which he worked.

Speaker Well, both both Jerome Robbins and Leonard Bernstein had these careers where they mix the high and the low, so in the case of Bernstein, that meant writing what he thought was his more serious music for orchestra, chorus, whatever, along with the Broadway shows, which ultimately he stopped doing. Robin’s left the Broadway theater to do his main love, which was the ballet. And of course, this has created a number of dances that endure and that are considered classics of the ballet repertoire, whether it be Goldberg Variations or Dances of the Gathering. I think that. What’s fascinating about American culture in general is that this high mixture informs a lot of our greatest artists, you could also say it’s true of Duke Ellington, for instance. You could say it’s true of a lot of writers. You know, we have we have great writers who write in what’s called genre fiction novelists and so forth. I think that in a way, the fact that Bernstein and Robbins felt it, at least to an outsider, seemed like they felt a little bit guilty about their so-called low work.

Speaker Their theater work, I think, was to the detriment of both of them, more to Bernstein than to Robbins, because a lot of people would say, including me, that Bernstein’s knowm theater music never was lived up to the music he wrote for West Side Story and Candied and Trouble in Tahiti, his his best theater work. Robbins did do great work in the ballet. That does does hold up. But I think it was a loss to the theater that in that time, the 1960s, he felt there was something sort of, I suspect, cheaper or commercial, which there was to some extent about doing the theater. And so he divorced himself from it, although he would periodically try to get productions going and played around with various productions and never reached fruition until he did Jerome Robbins Broadway, which was just a compilation of his old Broadway work. I think that that was a loss to the theater or maybe a loss to him, just as I think Bernstein’s defection from the theater was definitely a loss of theater and also, in Bernstein’s case, something of a loss to his career as a as a composer.

Speaker He wrote The West Side Story changed theater forever. How did he do that?

Speaker Well, that story changed theater because it was.

Speaker As if for the first time, something modern and new was crashing into the commercial Broadway world, if you look back in that period, it’s very interesting because in 1956, the year before West Side Story, when the biggest hit on Broadway was My Fair Lady Waiting for Godot in its first American production with Burt, LA came to Broadway and flopped. Also in 1956, Long Day’s Journey into Night was posthumously produced, was the first time it was produced and was was a success on Broadway. But meanwhile, The Iceman Cometh and O’Neal in the failed during World War Two and Broadway was being successfully revived off Broadway for the first time. You had all these forces happening, the theater trying to push it in a new direction. And then you had on top of them West Side Story come along, new young writers, new young, but not so new, but still young. Director, choreographer in Robbins’ into this Broadway that was still cotton candy to a certain extent, tired businessmen’s musicals, cheesy sex comedies that you’d now see as sitcoms on on network television, but then were standard fare for the Broadway commercial theater. So you used it really sort of consolidated this wave of change that would ultimately lead to the rise of off Broadway, a nonprofit theater which was still in a very embryonic stage off Broadway, and the emergence on Broadway of artists who wouldn’t have been presented there a few years earlier, such as Edward Albee, would be followed, you know, not long by Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, which never would have happened in the pre West Side Story, Broadway.

Speaker Would you say are the distinctive qualities of a Robin?

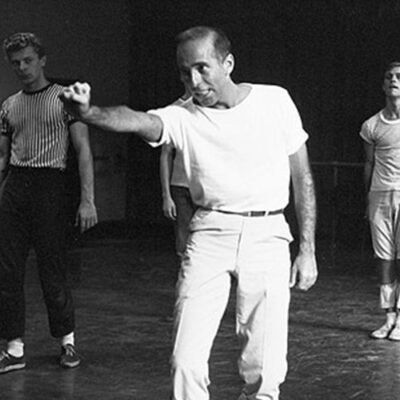

Speaker Distinctive qualities of Robin’s show include, besides terrific dancing, obviously a lot of speed and movement, they just keep moving the way film keeps moving. If it’s paradoxical in a way that he never became really a film director or a successful one, because he might have been a terrific one, because he also had a great eye and nothing is left to chance. His work is so detailed. So sometimes in subsequent productions when people are restaging his work, you don’t really it’s like a reproduction of a pain. You don’t really see what it was like when Robin’s, for instance, famously insisted in shows like West Side Story and Fiddler that every chorus member have a specific character that was generally new for the most part. I mean, that was that was really unheard of generally when you went to Broadway musical, you would say, you know, male dancers, female dancers. But if you looked at the program of Fiddler on the Roof, unlike any other show running on Broadway in 1964, every single character in that chorus not only had a name, but had a specific character and attitude on stage. It extended to incredible care about the design. I worked on a book about two decades ago about Boris Aronsohn, who would go on to design a lot of the famous print Sondheim shows, but designed to fiddler for Aronsohn.

Speaker And he did not. Ramas did not want an imitation of Marc Chagall.

Speaker He wanted a version that would make it new and fresh and would allow a huge performer like Marsteller Zero Mostel to be center stage. So his collaboration both with with Boris Aronsohn, the set designer and for that matter, Petition’s, that brought the costume designer, and Jean Rosenthal, the great lighting designer who also worked with him on stuff. And City Ballet was was down to every last detail, nothing. And that was you know, that’s a kind of perfectionism that then and now is very rare in the theatre or in art in general.

Speaker And certainly in show business, it’s yours. And so what do you wear on this show?

Speaker I think Gypsy is is one of the great American works of art, period. I have never tired of it. I first encountered it on a record when I was 10 years old. I’ve seen countless productions of it good, bad and indifferent to the dinner theater. I’ve seen it with all the great stars who have played it more or less. It always works. So. So why is it so? Why is it so great? I think it’s hard to separate, separate out the various components because it was just one of those rare things where an unlikely group of people in some ways came together. They wrote it incredibly fast and Robin’s contribution is huge. But it would be. But so is Julie Stein. So as Arthur Laurents and so is Steve Sondheim’s. I think that.

Speaker Where you see Robins is again in some of the thematic stuff, the sense that you’re taking a a tour through an America that is changing as the characters change. I think that also you see it just in the cinematic use of the stage, most famously, of course, in a number that’s now so well-known in revivals, people applauded even before they see it, where you see through sort of a strobe light effect, you see the Young, Joon and Louise age into adults, young adults, seemingly before your eyes by magic. The show never stops moving. On the other hand, he had Robins at his disposal, a fantastic book by Arthur Laurents, who was himself a very good screenwriter and playwright that just keeps moving and moving and moving. So it all just came together. And not everything Robbins did was perfect as a famous fight during the tryout of that show, for instance, when he wanted to cut a song called Little Lamb, that it’s not only a wonderful song, but if you see the show now, it can actually be an emotional high point of the show. So and so. There’s a lot of bruising along the way and all these Broadway collaborations. But why is Gypsy hold up so well? I think its themes are so timeless about parents and children, and I’ve found in taking children to see it myself singing as a child. They relate to it one way and respond to it even if they don’t know what vaudeville or burlesque is, which they’re unlikely to know. And when you get to be an adult or a parent yourself, you see it through another lens and it’s still powerful. And it’s really just an amazing piece. And almost every line in it lands. Every line is quite moving. The plot forward is often witty and Arthur Laurents script and has a has a subtext about character. The same time you have this great Célestine score with Sondheim pushing Stine, I think by his own young talent to even go beyond his own high level and numbers like Rose’s turn. And you have these lyrics by Sondheim when you think that he was in his 20s when he was writing these really profound lyrics about relationships between parents and children, it’s you know, he could write something like Rose’s turn. It’s almost mind boggling. And then you had Robins. Who? Who? Put it all together and and gave it a look and a feel that in itself is sort of almost Brechtian take on vaudeville itself, a series of vaudeville turns.

Speaker Um, you wrote with some affection about Peter Pan.

Speaker Tell me to. Peter Pan, for a lot of people of my generation, was the first Broadway musical we saw because it was a flop on Broadway in 1954 and only ran a couple, two or three months and then immediately and something that was considered radical for the time, they moved it to the whole production from, I think, the Winter Garden to a studio in one of the five boroughs and just shot the show live on television. And it’s interesting, you can see why the show was a failure because, you know, they fired a set of songwriters out of Tampa, another set of songwriters, not really all of one piece, but again, it’s pretty timeless material about childhood and robins at least. And I never saw the stage version, but I certainly remember vividly my whole neighborhood coming to a halt to watch the live TV event with Mary Martin. It was just it’s a magical piece as the jamboree underlying material is with some very attractive songs in it. And the staging, at least judging the TV version is not so exceptional. But their numbers, like I’m flying that just again, sort of are images we can’t escape. I think they’re part of the American language. They’ve been seen so much. And while Peter Pan flew in many productions and on the page before this early 1950s musical version, there’s something about the way you see the Peter of Robin staging and her kids go into the sky on wires. It’s just touching and exhilarating.

Speaker Would you assess the way you wrote about what was.

Speaker Well, Jerome, Jerome Robbins Broadway was what it was. It was a beautiful compilation of the greatest numbers from all his shows, including some shows that people like me were too young to have seen, like high button shoes. And it’s it was wonderfully done.

Speaker It’ll never be done that well again. It cost a fortune. Robbins was alive and could do it. He could drive everyone to distraction and get the best dancers to get what he wanted. And it’ll never you’ll never see those numbers so pristinely again. What it couldn’t give the audience, by definition, was the cumulative effect of a Jerome Robbins musical because it was a medley. It wasn’t the actual show. So you can’t fault, you know, a duck for not being a horse. It just it was a review in that sense. Wonderful preservation of these numbers. But the whole point about Robbins as a as a Broadway musical director was it wasn’t just that he could do terrific numbers like the Bottle Dance and Fiddler.

Speaker He could also make the whole show move and dance and that you can’t get when you slice it into pieces for a review, however, beautifully done.

Speaker When you wrote about it, you talked about its meaning somehow and you were just addressing the whole body of his work. You know, I can’t repeat what you said, but. It was it was very moving.

Speaker Well, I think I think I think what you have to remember is that when when Jerome Robbins Broadway was done on Broadway in the late 80s, he had been going from Broadway for over 20 years.

Speaker In the years just before Jerome Robbins Broadway opened his three obvious successors in terms of being a great director, choreographers who could make a show work all the way, all the way through, and that dance all the way through and give it that seamless quality.

Speaker Robbins did.

Speaker Michael Bennett, Bob Fosi and Gary Champion had all died at the time. Jerome Robbins Broadway with them being gone. You had this new era of spectacular musicals, the British, the big British musicals, the reigning hits on Broadway were, you know, Cats and The Phantom of the Opera, which are the antithesis of what Robins did. Whatever one thinks of them, they were cats had dancing, but they had no it had no story to tell, really. Fan of the Opera House, no dancing. Their song spectacles, they feel their stolid, their sort of a throwback to some something that predated Robi’s, which doesn’t mean that people can’t like it, enjoy it, but it’s more like the era of operetta than the modern Broadway musical.

Speaker So it’s rather poignant to see Robin’s more than 20 years after he’d said goodbye Broadway comeback, remind everyone of what he had done at a time when other people can do it were non-existent or dead, and when the Broadway musical had gone somewhere else to something much less sophisticated, I think.

Speaker And when it was also clear Robins was just coming back to give us this reminder and then went on his merry way again and never returned to Broadway again.

Speaker He was, of course, known to be difficult, and the word you used, his obituary was monstrous. So how do you account for the tenderness and the vulnerability in some of his work, such as death?

Speaker I think it’s you know, I did I did not know Robbins personally. So I, I can’t attest except by hearsay to what he was like to work with. But we you know, we all know the stories. When I did witness, which was absolutely fascinating, was when I was in my early teens and was able to sneak in to essentially cast meetings and rehearsals of Fiddler on the Roof during his Washington trial when adults were barred by him. But because a friend of mine and I were teenagers of the set and so he didn’t see us, I saw the incredible animosity between him and Zero Mostel during that show. I mean, basically, they seem to hardly speak to each other. And Mostel openly mocked him, all of which, of course, dated back to the blacklist and their being on the opposite sides of that. But I think that you can’t make a correlation between the way people or artists are in lives and what their work is. It just you know, there are there are artists who were very nice who write very, you know, nasty stuff in there and there. If Robbins was a difficult, thorny, trying perfectionist, that not necessarily mutually exclusive with being a tender artist and the feeling it doesn’t take away from the feeling in his work. I’ve learned in my years as an arts journalist it’s best not to meet most of these people because they never really match up to their work. And and that’s life. And that’s one of the mysteries of art. And we should just go with it rather than, you know, Frank Sinatra. Not a nice guy, but the tenderness and the greatness of his best work is, you know, beyond compare.

Speaker So tell me a little more of the middle of rehearsal. What was your doing?

Speaker My memory is he what we would my memory of what Mostel was doing. It was the morning after the show opened in Washington and Robbins had called the cast for a meeting to discuss what changes they were going to make or not make. And so in this empty theater, the National Theater in Washington, August of 1964, when the show was trying out, I was 15 years old, sitting in the back, the cast was seen in the first two rows of the orchestra and Robbins was leaning against the pit to face them. The curtain was up on the, you know, dark and set. And Robbins kept saying, we’re z, we’re zero.

Speaker And the cast just sat there and said nothing like, you know, like it’s the disciplinarian teacher and they’re not going to get caught up in this drama.

Speaker And then M.L. appeared on stage and started making what I guess we’d call semi obscene gestures, mocking Robbins with the cast, at least initially pretending not to notice. How could you never not notice Zero Mostel clowning around?

Speaker And ultimately they started tittering. And then Robbins joined the group and everyone sort of pretended it didn’t it didn’t happen. And it was fascinating to watch Robins, because the other thing that people just to talk about Robin’s perfectionism is second, when I when I was a kid and I worked in the days when Broadway shows, tried at a town routinely almost gone. Now, I worked as a ticket taker when I was in high school to try out a very busy try house in Washington. And it was fascinating, of course, to see shows come in that were a mess or failures and that the creators would try to fix, usually fail to try, but sometimes shows would come in and be enormous hits from the get go. And one example was Fiddler. Fiddler got its first reviews and Washington had previously played it. Another try out town, Detroit. But there had been a newspaper strike and no reviews at all except a pan and variety then came to Washington with no advance opened. It was instantly clear, sitting in the audience that the show was an enormous hit. It was going to be one of the biggest hits ever. It got great reviews. And yet, for the three weeks in Washington before they came to the Imperial Theatre on Broadway to open up, Robbins met with that cast every day to perfect it. Now, if he listened just to the audience and the reviews, he had to do nothing. No one criticized anything about it. It was a perfect show, beautifully cast, but in fact made some significant changes. For instance, he kept coming, kept the cast coming back because there was no dancing in the second. Act well, in the end, there is no dancing in the second act, fiddler. Not that he didn’t try would he would bring people up on stage, work with them, try to get a dance going. In the end, there’s a tiny little fragment of dancers, Hovell, a sequence for another show. But he did put in the bottle dance in the wedding scene at the end of the first act that did not exist when the show up in Washington. That number already, you know, was sunrise, sunset and it was already a hugely successful number. Why improve it? He found a way to improve it. He took a song away from one character and gave it to another and changed its position between Act one and Act two. He kept fooling with the was essentially the last song in the show, which was a show song called When Messiah Comes, when it opened in Washington. And by the time it opened on Broadway, it was replaced by a song called On Ataka. But he kept fooling with things he wouldn’t he wouldn’t take yes for an answer. But that’s what great artists do. He tuned out the audience, tuned out the great reviews and said, this may be great, but we can make it 20 percent better. And he did.

Speaker What director choreographer today measures up to him?

Speaker I’m not going I don’t I don’t know, I don’t I don’t I don’t want to I don’t want to talk about that. I’m not fertile. And maybe there’s someone I’ve missed there. Really I don’t even know who would be in the running. I, I, I don’t want to be insulting to people. I just don’t think there’s anyone. Even with that ambition, there’s very few director choreographers, period. The you know, some of them you know.

Speaker What I can say is it’s it’s is in some ways, this is if the Robbins’ revolution never happened because there really aren’t very many director choreographers now. So if you look at the hit musicals in the theater, whether you like them or not, whatever, whatever they are, whether it be Hairspray or the Disney musicals or rent, the directing and choreography are divided among two people. Generally speaking, it’s so hard to do what Robinson, Michael Bennett and Gower Champion and Bob Fosi did, and we have to hope some will come along.

Speaker There’s not also the volume of work to train people anymore because the whole the whole economic situation of Broadway has changed so much. It’s almost apples and oranges to compare that period to now.

Speaker And that’s why I know, you know, I.

Speaker I don’t I really don’t want to be I mean, I could say I could say, you know, people like Stralman will see they’re still relatively early in their careers.

Speaker But I don’t want to get into the into you know, in some cases, I mean, I’ve seen all the shows either, so I don’t want to take that one, if you don’t mind.

Speaker You wrote the Jerry was a giant in our culture.

Speaker Well, I think that Robbins was a giant in our culture for. Several reasons. First of all, he was the principle creator of. Three of the most enduring works in the history of the American musical theater, the American musical theater itself being one of the few great indigenous art forms invented by American culture. I think that he has left. A really impressive and I I would guess durable collection of ballets to American dance, is he George Balanchine? No, but but still some fantastic work that I suspect will hold up and and thrill audiences for a long time to come and remain constantly in repertory and dance by all sorts of different troupes around the world. And I think, you know, we’ll look back and we’ll look at him as we do it to Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim among these sort of towering people that combined high culture and pop culture in the mid century and created material that has turned out to be, you know, have no shelf life, seems to seems to just go on and on and on.

Speaker People never stop being interested in West Side Story, even though and and thrilling to it, even though the socioeconomic world it describes is completely different in terms of ethnicity and everything else. Now, the language that Arthur Laurents invented to have this kid speak is was artificial, deliberately artificial, then still is, but still speaks to people. Look at Gypsy, which was not one of them. Neither it nor West Side Story were among the longest running musicals of their time. They were neither of them with the biggest hits of their season. And yet they’ve laughed and laughed and lasted because they so speak universally. And Robins had a big role in them, as he did in Fiddler on the Roof.

Speaker He was actually QSI, he was fairly apolitical and very private about his sexuality, but in the end he became very active in gay rights causes and also in AIDS activism. And I’m wondering if you I think you’ve written about some of these issues about why a person would do that in that time.

Speaker I can’t talk about Robbins’ in the 80s and why he he changed. I do think that. Robins, in terms of, you know, I guess being essentially a closeted gay man for much of his career was fairly standard for that time.

Speaker It’s not as if, you know Tennessee Williams, although anyone who knew anything about the theater knew that he was gay. The truth is, many Americans did not. He was not, you know, in those years, openly gay was a different world. It’s hard to judge people by the standards of today, in 1955. And the truth is, I grew up a theater not in the 50s and early 60s. I never knew anyone was gay. No one ever talked about it was a different it was a different world.

Speaker And people just didn’t talk about it on the McCarthy period stuff, which is also before my time. I think that. What’s interesting about Robbins is he did name names, a lot of people never forgave him for it and and to my mind, with good reason. Yet there were people who were on the other side of the black list, including people who were blacklisted, who perhaps with some real reservations and not a great deal of warmth about it, did work with Robbins. And that would include Arthur Laurents, who certainly, you know, wrote the way we were, for heaven’s sakes, and but who left the country at the height of the blacklist, but who worked with Robinson, both West Side Story and Gypsy Zero Mostel, who worked with Robbins on both. A funny thing happened where the forum where Robbins came in to doctorate at a town and West Side Story, assuming Zero Mostel worked with with Zero Mostel, who worked with Robbins on finding out in a way, the forum, and then on fiddler Jack Gilford, who worked with him in Forum. Granted, Robbins was brought into the show out of town, but they didn’t quit. But I think I think that the fact that Robin’s name names it didn’t. It never really. I think can alienate a certain amount of the New York culture from him, including the Broadway theater culture, and particularly given that he was sort of apolitical and did it for reasons that I think are largely viewed as mainly careerists, which would not make him unique. The musical theater in a period that ran from roughly the 1920s to the early to mid 1960s was synonymous with sort of A-list American pop culture. So if the big hit song in Oklahoma was, Oh, what a beautiful morning or in My Fair Lady on the Street Where You Live, those were the number one songs in the country. Broadway musicals were showcased on the cover of Life and Time magazine. They they occupied a place in the American culture in a way that American Idol does now like and particularly in the days before television. But even in the first period when television overlapped, Ed Sullivan, the highest rated variety show they’d have, he’d have, you know, popular singers, but he’d have every week he’d ever seen from a Camelot or whatever West Side story that ended. And it ended abruptly and kind of shockingly for people in the Broadway theater. And it ended because of the advent of rock and roll. The whole culture shifted and Broadway did not shift with it. And so you get into the early 60s and you have what we now look at as sort of the last hits of that Broadway era. Hello, Dolly. Funny girl, Fiddler on the Roof. Hello, Dolly. One of the last ones that the title song of that covered by Louis Armstrong was the number one song in the United States, even though Rock had begun by then, by the time meet the Beatles happened, it was over.

Speaker And once the British invasion sort of solidified and increase the whole of rock and roll in American culture, combined with the other revolutions of the 60s, that was the end of the Broadway musicals being a major as a major player and is not to this day. Yes, they’re their hit shows, but even a big hit. Like a Phantom of the Opera or a rent or a Lion King does not dominate the culture, it doesn’t dominate the billboard lists, it doesn’t dominate the covers of magazines the way the Broadway musical did. It’s just incredible to think now.

Speaker But a big Broadway musical hit would get the kind of attention now that, you know, Nurse Betty would get when it became a header or Saturday Night Live. And as and it’s gone. It’s now the Broadway musical theater is not dead. There are hit shows even as we speak. You know, there things like Wicked, which have four companies around or Jersey boys around the country.

Speaker But it’s still it’s a it’s a niche entertainment compared to what Broadway used to be and the art musicals, the kind of musicals that Robins would have done, which are represented today by the musicals that Steve Sondheim still does, or a show like of Grey Gardens or or, you know, any sort of artistic adult musical in that way. There are niche within the niche. Say, you know, they they have a following, but they have a following in the same way that a good literary novelist might not in the way the mass way that my fair lady, whether you were in Peoria or wherever, you had to have that record in the way that now you’d have to have, you know, a hip hop record or or, you know, whatever, Coldplay, whatever, you know, whatever’s popular, it was all wiped away.

Speaker OK, last question, OK? Speaking specifically about his work, which do you think the Jeri’s greatest achievements in among?

Speaker I mean, his Broadway work.

Speaker I think it’s hard to say. I think it’s the nature of Robinson’s Broadway work that it’s hard to say one thing. Was greater than the other because he served material that was written by others and did an exquisite job with everything that was handed to him and made it better and helped, you know, beautifully achieved on stage.

Speaker So if my favorite of his shows is Gypsie, that doesn’t necessarily mean that that’s his best work, because it’s also Arthur Laurents, Julie Stine’s and Stephen Sondheim’s work. That said, if you look at his numbers and the things that if you think of Robins in his Broadway guys as opposed to the ballet half, there’s certain things I think just leap out as being, you know, essential robins. Certainly the opening of West Side Story is just one of the most, you know, remarkable openings ever. And whatever one thinks of the rest of the show is just one of the most amazing bits of staging with that Leonard Bernstein music. I think in in Gypsy, you think of the way he handled the vaudeville parts of it in the way he handled that famous cinematic sequence that shows the two girls growing up before your eyes and making it seem like a movie and magical and fiddler.

Speaker I think you think of not so much specific choreography, not the show stopping numbers like the bottle dance.

Speaker But again, you think of the opening number of tradition of him using actors, body space, light music and scenery and storytelling altogether that whatever however long that number is, eight minutes, 10 minutes, you suddenly are situated in an entire community with all its happiness, its tragedy, its warring elements, its friendships, its love, its familial elements, its humor. It is all there. And he gives it to you with the help of all his collaborators, but he gives it to you in a way that’s so visceral and theatrical. It’s not at all intellectual, just enters your soul, really, and orients you into the show so much that by the time you actually if you look at as I look at the show, as the years go by, the show isn’t nearly as interesting as that opening because the character, it almost can’t live up to to that that incredible panoramic view that uses all the arts of the theatre of which dance is just a tiny one to give you a whole world, you know, right in your lap.

Speaker I have one other thought for all. Robin’s really serious and and significant. Artistic ambitions and a team is one thing that really loved his work that not always enough credit is given to is his real sense of love for the really low kind of American comedy and show business.

Speaker And it manifests itself, of course, very much so in Gypsie, where you see these really tacky vaudeville acts and ultimately strippers acts that he he obviously he just loved and can make them funny because he loved them. And you see in something like the the Keystone Kops ballet in high button shoes, he loved Max Senate. He loved he loved Irving Berlin. You know, he always was. I think he was friends with Berlin and was with a few people, Berlin, who lived to be, you know, over 100 and was sort of recluse for years. He’d always talk to Robyn’s, won her and, you know, who is more sort of brassy, sassy American than Berlin. He’s the antithesis in a way of Leonard Bernstein.

Speaker But Robbins had an appreciation for that part of sort of Americana, too.

Speaker And so that’s why he could do a faultless Astaire. No, like all I need is the girl in Gypsy. It’s why in Fiddler, even perhaps even a little bit out of tone with the show, something like the dream sequence in the scene with Golda and Tavia in bed. And she has a dream and her nightmare. It owes as much to sort of radio comedy of the 30s and vaudeville as it does to slow like in the shtetl and and even a little bit in West Side Story, the kind of knockabout humor of, gee, Officer Krupke, abetted by those great Sondheim lyrics. But he he like that stuff.

Speaker He liked, you know, numbers like, excuse me, he like that stuff.

Speaker He liked he kept trying to get that. No Mr. monotony that Irving Berlin wrote. And they never could quite fit in the show. Right. He even put it back in. And Jerome Robbins Broadway.

Speaker It was like a running gag between him and Berlin. And one and one of his wonderful achievements, I think two and relatively early on is the Uncle Tom’s Cabin Ballet. And King and I is wonderful because it isn’t it isn’t Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Speaker It’s it’s a Asian societies, half known, half translated, half remembered, half, sort of almost like rumoured version of what Uncle Tom’s Cabin and what Harriet Beecher Stowe meant, refracted through some sort of idea that the Asians had of American showbusiness, refracted through the ballet sensibility and sort of taste of robins. And so you have this sort of incredibly I hate to use the word unique, but it genuinely is unique. It’s like it’s it’s an it’s an Asian cultures take on an American, cultures take on an African American. Cultures take on slavery as seen visually and with a great sense of humor, as well as sort of social justice and compassion by robbins’. And it’s just remarkable. Or you look a coarseness in his ballet work and you see something like I’m old fashioned is a tribute to Astaire and Rita Hayworth. Actually, it’s just, you know, awe and fancy free. So he loved that he had this real joy about sailors on leave, even as he liked Brecht.

Speaker And even though we have, you know, graver things to say about American urban fishers in in West Side Story.