Speaker OK, I’ll just say that it is March 26. This is the first tape of our interview with Jeff Colvin for Henry Luce in the making of the American Century.

Speaker Let me start a little broader and ask since in the context of what we’ve talked about before, about who knows who to that in a film like this, in a project like this, which has some pretty you know, we’re trying to give it some scope. What you think it’s important for us to convey or tell people about how we use the.

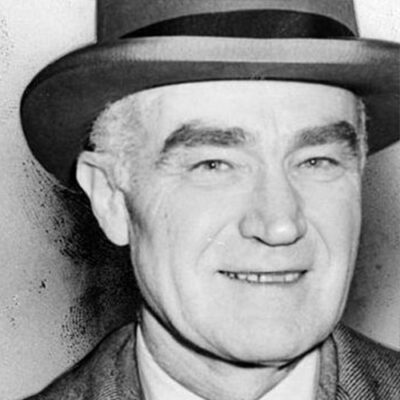

Speaker Good question. Probably what’s most important about Henry Luce, most important to remember or for people to know is that he attained a level of influence in the country in matters of politics, but also taste in popular culture that it’s very difficult to imagine any one person having today. And of course, he did it when the media were the media. He was in were print. Nothing more advanced than that, but still through these properties that he invented and built up from nothing. He reached a level of influence in the country that we just don’t see anyone having anymore today.

Speaker How did he get this? Did they get to that point?

Speaker He achieved this level of influence in an interesting way because he started out with nothing. I mean, he started out, of course, coming from a wonderful background and with a wonderful education and so forth, but nothing in the way of finance or a background in media or a family business that he could build upon or anything like that.

Speaker He did it, first of all, by having actually a better idea when it came to media. He had this idea for Time magazine that truly was a new thing. Nothing like it existed. It actually was a good idea. And he and Britain hadn’t. And then all the other people they brought along with them were able to execute it in a terrific way, which is often where great ideas fall apart, of course. They really were able to make something of it and it truly was new. This is something that looking back on TIME magazine 80 years after it was founded, people might forget it truly was new at the time and it grabbed a level of attention and managed to create for itself a level of respect that. Eventually, over a remarkably short number of years, actually brought loose. Substantial power. Now, that raises the question of. How did he how did he do this? What was it about Time magazine first and then later fortune in life?

Speaker But you must go back. We’re talking about how. Luce came by this, right? Right.

Speaker He got so much influence and so much power because ultimately because he had this idea for a magazine, that really was a better idea. It was something truly new which people tend to forget. So many years after Time magazine was founded, but it was a new thing. There was nothing like it at the time. And he and Britain hadn’t. And the people who came with them really did execute it extremely well, which is where so many great ideas fall apart. So he had something that.

Speaker Did many things at once. One. It appealed to a very large audience. And that’s partly because of the particular style it had, even that bizarre Time magazine language that they used in the early days, partly because of the level at which it was pitched, which you famously described as middlebrow, which is about correct.

Speaker But it appealed to a mass audience. And yet with a certain level of intelligence and the subject matter that it chose, which was the news, it was all about what was really happening in the world that week. And so that appealed to people. And B, it got the attention of the news makers. The people of power in the United States suddenly had to pay attention to this magazine because it was all about what they were doing. And it was pitched and produced in such a way that people really were reading it. And there was nothing in the mass media like that at the time.

Speaker I’ll stop there, but I could go more into the sort of mass media situation in those years. OK, OK.

Speaker The mass media landscape in those days, starting in the 20s when times started, was, of course, very different from what it is today. But in the world of print media, radio scarcely existed. And then the sort of big factor was something called the Saturday Evening Post, a weekly magazine. But it wasn’t about news. It was hugely influential. An enormous circulation, something like two point two million in a country with a population much smaller, of course, than the population we have today. And it was a big, powerful magazine, but it wasn’t about the news. And so there were other magazines that were about the news, but they were smaller, more specialized, or they were monthlies. So to come out with this newsmagazine that was weekly and of course, that was precisely the positioning time, the weekly news magazine. This was a new idea. This was a new niche. As for getting people in power to pay attention to him and consistently through Luce’s career, this is a theme that you see. You know, he was starting out from nothing and he wanted to get the important people in the United States to pay attention to him.

Speaker One way was to write about what they did. Another way, of course, was to write about them in the way he did. And it became famous and it even became the butt of jokes. But time would describe people in a rather unflattering way. And nothing like this had been seen before. Not today in the realm of talk radio and cable TV where people can say anything at any time. It’s hard to shock anyone. But back then, if Time magazine referred to a senator or a captain of industry as a pig guide or bag jostled or large punched as it did regularly, it got these guys attention. And suddenly they realized that they didn’t want to be described that way, or at least they wanted to have some. They better pay attention to what TIME magazine was going to say about them. And it worked.

Speaker Now, there’s something else that goes along with just what you’re saying now, which is. Time for the longest time and for the most part. It’s covers for people. Yes.

Speaker So, yes, if you talk a little bit about how its approach was to tell this, one of Luce’s most important insights was that people were basically interested in other people. And so he told the news through the people in the news, which again today doesn’t sound like such a, you know, an innovation. But at the time, it was there would be more telling of the news through events or through ideas or things like that.

Speaker But to tell the news so much through the people in the news was a new thing. And in later years, Luce was sometimes criticized for it. And he would always say, look, you know, I didn’t invent it. The Bible invented it. This is the way stories are told. And of course, he was right. There was no better way to appeal to readers. There’s no better way to get a large audience than to tell stories through people and all through times history. From day one, it would tend to put people on the cover. By the way, there’s a sort of interesting counter fact with regard to Fortune. It wasn’t until 1963. Here’s a magazine that started in 1930. It wasn’t until 1963 that Fortune put an identifiable living person on its cover. And that was Alfred P. Sloan, who at that point had been retired for decades as chairman of General Motors. But that was the first identifiable living person on the cover of Fortune.

Speaker Why do you think that was?

Speaker It is interesting and.

Speaker In part, I think it’s because fortune started out as intended to be the most beautiful magazine ever created. And when it started out, it was generally agreed that, in fact, Luce had succeeded, that this was the most beautiful magazine ever created. And I think part of the sensibility of the time was that if you’re going to make something intended to be beautiful, then you put artwork on the cover. And over the years, Fortune had artwork created not only by artists who painted, but by graphic artists and other kind of artists. But it was intended to be slightly abstract, slightly elevated. It was intended to be beautiful art. And that idea just didn’t intersect with the idea of putting a newsmaker or any identifiable living person on the cover. And the heritage was very strong from those early days, and it carried on for years and years and years. And so finally they saw their way clear to putting an identifiable living person on the cover, namely the man who had been the chairman of the largest corporation in the United States and who was clearly its most important chairman, Alfred P. Sloan. So it was OK to put him on the cover and they did.

Speaker When you were younger, did life for design come to the house?

Speaker Absolutely. Like so many people, I grew up in a home where Time magazine arrived every week and it was very important. I grew up, as it happens in South Dakota. Now, like millions of people. I didn’t have access to a big metropolitan daily newspaper. And even when I was a kid where we grew up, we only got two channels of television of black and white TV. And you didn’t watch much of that.

Speaker TIME magazine was really important and it came into our lives like it did into millions of other people’s lives as a place where you learned all kinds of things about the news of the week and other stuff as well that you didn’t know. That was also part of the insight that Luce had because there wasn’t a national news media at that time.

Speaker There simply wasn’t.

Speaker There was also, as you said, many other things. So his concept of news was different. Yes, yes.

Speaker His concept of news was again different from what was common at the time. It shaped the concept of news that we have now come to know and that we see in publications and on television and so forth. But at the time, he knew that he wanted a mix of what was happening in Washington, of what was happening in business, although not too much of that, but also what was happening in books and culture and things like that. That’s what came to be known as the back of the book, the feature departments. That was important from the very beginning.

Speaker What about love? Did you read Life?

Speaker Absolutely. Life magazine was again this thing, this this year, of course, in the old days, this enormous physically large magazine that came into our lives. And personally, I loved it. I loved getting it and seeing it every week. One of the editors years later said that putting out life was like putting on a new Broadway show every week. And, you know, on the receiving end, that’s sort of what it felt like. It was a fabulous entertainment. It was a great thing.

Speaker When it came. How do you how do you pull?

Speaker Read, I said very simply, I sat down with it or when I was a kid, I more likely got down on the floor with it and just started from the front. I just saw, of course, the back page was probably always my favorite page, but still I just started from the front and went through it. And again, in this age, when either there wasn’t any television or television wasn’t nearly what it is today and maybe a couple of black and white channels.

Speaker Then to see everything you could see in this big picture magazine was an experience that was extraordinarily rich and valuable. And there was also the magic of the frozen image that to some extent people have lost touch with today because we do see everything moving on television. But you recall the fascination people had with the photographs after September 11th, with the photographs of what had happened over and over. You heard people remarking on how different it looked when you saw printed photographs and there were special editions of many magazines that were just full of those photographs. The frozen image, even though we had seen all of that stuff on television endlessly before any of these printed images came to us, we were still fascinated. The frozen image does have a certain power, the ability to stop time, and then your ability to look at it and study it is something that.

Speaker We don’t.

Speaker Understand or we don’t know as well today as we did back then. But that was part of the incredible power and appeal of life also.

Speaker I don’t know what your. Political background was or your parents? More, actually, more your parents political background. But it seems that there are a lot of people who have this love, hate relationship with Tony. Right. If you can describe with us. All right, ahead. But they sort of at the same. Right.

Speaker Right. Well, of course, part of Time magazine’s whole approach. And by the way, it was stated by loose from the beginning that this would be the case was that time would not be impartial. Time would tell you the many different angles of a story, the many different points of view. But ultimately, it would have one point of view, one of those points of view for its own. And. If you read the magazine, you would come away knowing what that point of view was and it was not going to make any bones about it. Well, of course. Luce was the essential Republican and that came through. And of course, in the old days, it came through much more strongly and personally. Growing up, the surroundings were generally Republican. I think my parents, as far as I could tell at that time, were and perhaps as a result of that, I don’t recall thinking of time as having any political bent at all. In retrospect, of course, it’s because it’s political bent and the families. What I was surrounded by, we’re pretty much in sync. So it was a good fit. But of course, that was part of time. You knew where it stood and it would report all. I’m sure the reason people read it and still yelled at it was because it was telling you interesting material for a lot of people, material you hadn’t read anyplace else. It was valuable. But at the same time, you know, Eisenhower was always striding purposefully and stuff like that. I mean, you understood that they had that point of view and it was being woven in throughout the magazine.

Speaker How did how did Lucy Luce’s.

Speaker Being a missionary kid. Sort of inform how he approached his career since.

Speaker It has always seemed to me that the influence of Luce’s missionary background or his parents missionary background and his own childhood was that he didn’t see a person’s path through life as necessarily requiring business or a job or the kinds of things that most kids grow up sort of absorbing. And assuming he saw that you didn’t have to have a life like that. I mean, you could have a life, as his parents did, where they had they were driven by something much larger and much higher. And somehow they were supported. I mean, they lived. They made a living. They got through life. But they were driven by something larger and higher than most people see their parents being driven by. And. It seems obvious, but I don’t think it’s any less true that he carried that into his own profession. If you read the prospectuses for those magazines for time and for Fortune and for life, there was always something in there about this being for the good of the nation. These things were intended to improve the nation. And I’m certain that that was sincere. He really did mean that. He wanted power and influence for himself for sure. He made a lot of money, although there’s not much evidence that he really was in it for the money. But he was in it, at least in part because he had a mission. And I think what he clearly considered a noble mission was a good and right thing for him to be doing. And it not only explains the content of a lot of these magazines, but it helps explain the fervor and the energy with which he went at it, because without that, these things never would have succeeded as they did.

Speaker That little noise I heard wasn’t a really good.

Speaker How did. The time convey its political bias. It didn’t have an editorial write it and go about doing it right.

Speaker Times.

Speaker Time conveyed its political views not so much by stating them explicitly. It very famously didn’t have an editorial page and never ran an editorial until 1974 when it ran an editorial urging Richard Nixon to resign. And that got a lot of attention because it was the first editorial in the history of the magazine. Up until then, it conveyed its views, actually the way most publications and most media convey their views, which is simply by choice of story. What you’re going to run and what you’re going to not run. And then, of course, the way you tell the story, and this can be done in innumerable ways, obviously, you choose the stories that tend to convey what you want to convey. You ignore the inconvenient information when you’re telling the story. You can use the famous time descriptions of people that would either cast them in a very unfavorable light or would cast them as a in a favorable light by describing them as square shouldered and tall and clear eyed and things like that.

Speaker And then just little throwaway lines.

Speaker But it would be full of things about like striding purposefully someone else, you know, shambling, I mean, you would just a little choice of verb or adverb here and there.

Speaker Contributed to the effect. And the editors would sometimes say, look, we don’t say where we stand. But if you read the whole magazine and if you read it regularly, you’ll know where we stand.

Speaker That’s the way it worked.

Speaker Let’s talk about Fortune, because it gets you started to broach it. But yes, let’s let’s talk about how fortune came to be. Conceive of it. What did he say? Would it be? No.

Speaker Luce had this idea for a business magazine, and he had it in the late 20s, which makes perfect sense because, of course, the great bull market of the 20s was cranking up into very high gear in 1928 and twenty nine. And a business magazine was an obvious idea. In fact, his partner, Britain, had and wasn’t so keen on it. But that’s because he was preoccupied with time. A business magazine made all the sense in the world. And I think Lou’s had a few things in mind when he thought this up, one he wanted to get the attention of. The people who were in power in business as the stock market went ever higher. The nation became focused as it did again in the late 90s on business and stocks and things like this. These things that used to be peripheral to most people’s lives suddenly became central. And Luce realized he wanted to get the attention of the captains of industry, the great business people and bankers and financiers and so forth. Well, the way he would do that would be to start a magazine that would be about them. In addition, he did see a market niche. He saw an opportunity that was very legitimate. There were other business magazines out there, but they weren’t very elevated. They were often written by hacks. Their choice of stories was hackneyed. You know, it was all how to get rich in 30 days and things like that. It wasn’t nothing about them was very well done. And he saw an opportunity, a legitimate opportunity to put out a different kind of business magazine, one that would be very well done. And after all, this was for a class of people who were becoming very wealthy and more powerful by the day. And so he put it all together and he came up with his idea for the magazine that became Fortune.

Speaker Now, you mentioned before about you talked a little bit about the covers. Yes. This was. Clearly, no ordinary magazine, right? How did he come to conceive of it? As the was.

Speaker He decided that fortune really had to be absolutely distinctive and distinctive, primarily in its appearance, so that people without reading a word would know that this was a different magazine than he had all kinds of ideas for how to make it distinctive inside as well. But sticking for the moment only with the appearance, with the initial signal it was supposed to send to people. He decided it was going to be the most beautiful magazine in the world. It was going to be especially large and the art director we put in charge of it. Thomas Cleeland, was told that it was supposed to be the most beautiful magazine in the world. And he therefore chose this unbelievably heavy cover stock, this extremely beautiful paper for the editorial pages to produce. The magazine was an ordeal that is unimaginable today. Some of the pages had to be run through presses numerous times. Some pages had to be run through presses in New Jersey that could do certain things and then through other presses in Brooklyn that could do other things. And then it was all so big and heavy that it had to be stitched together by hand. It was then delivered in a cardboard box because it was so heavy and substantial that it couldn’t just be left loose. And it was sold for the astonishing price at the time of a dollar a copy or ten dollars a year to translate that into today’s money. Multiply it by maybe 15 or 20. So it’s nothing. This was audacious in the extreme. Nothing like it had ever been done.

Speaker What do I think we’re really.

Speaker So let’s talk about the inside. Let’s talk about the. His choice of editors, photographers. Right? That’s right.

Speaker Luce had a lot of ideas about what would be inside Fortune magazine, someone worked on some of them, didn’t he, by chance, saw some photographs that had been taken by Margaret Bourke-White. I think it was in an ad agency. He was visiting, but he saw them and said. Who took those?

Speaker And he found out who it was and he contacted her, invited her to come to New York to talk to him at the time, it all meant very little to her, but it turned out to be one of those just fortuitous pairings because she had an idea about photographing industry in a way that hadn’t been done before.

Speaker And he had an idea about a magazine of industry in a way that had never been done before. And it turned out to be just the perfect match. And so Margaret Bourke-White ended up taking some of the most famous, most iconic photographs that ever appeared in Fortune. And this was a great, great success for many years. On the other hand, on the writing front, his original idea was that the articles would be written by famous people, by notable business people and other famous people.

Speaker Well, even he realized that it was their ghost writers who would actually do the writing, but it turned out that even they weren’t very interested in in participating. The great captains of industry didn’t especially want to have articles that their ghostwriters would write for them, or if they did, they weren’t any good. And so that plan was scrapped.

Speaker And he moved on to plan B, which was to get business writers from newspapers and stuff. He figured every newspaper has a business section. We can hire the better ones from there. Well, A, they turned out not to be very interested. Who knows why? Except it may also be that in those days, especially the business pages of the newspaper were just about the lowest form of work that existed in journalism. It was just considered the bottom of the ladder often because in those days the business pages were slaves to whoever advertised in the newspaper. And so it wasn’t very good journalism. In any case. So in any case, that didn’t work out too well. And he moved on to Plan C, which was to get wonderful writers, just people who were wonderful writers and not worry about whether they knew anything about business. What he discovered and what I may say continues to be true today is that it’s very rare to find someone who, a, understands a lot about business and can read financial statements. And B is a good writer. And what he discovered was that it was a lot easier to take a poet, as he said, and teach them about business than it is to take a business person and teach him how to write. And so he ended up hiring as his well-known people who were indeed poets, literally, and other famous writers. Archibald MacLeish, James Thurber actually wrote for Fortune at one time, although these pieces were never signed. Russell Davenport later, someone who wasn’t a poet. John Kenneth Galbraith at Fortune and got them to write about business. And it turned out to work extremely well because these people, once they did learn about what they were writing about, could write the most engaging, captivating narratives that had ever been written about business. I mean, Luce’s stated intention was to create a literature of business that’s kind of high flown and ambitious. And amazingly enough, he succeeded in doing so with the writers that he brought on board.

Speaker At what point did he. Well, let me ask you this, how did Fortune. Evolve into life.

Speaker What’s the relationship between his experience with Fortune?

Speaker Oil, it’s a good question and I’m not sure I know it’s a good one. And I but I don’t know that I.

Speaker Have anything? No, thanks. Fair enough. Yeah. Then.

Speaker This is, again, more about him personally. Yes. Yes.

Speaker If I had had a store, I saw I had a story that didn’t tell about. Yeah. About the writers on Fortune. Let me tell that. Okay. No, no.

Speaker So loose hired all these poets and so forth, these storytellers, natural writers at Fortune, one thing about them was, A, they didn’t know anything about business, but they learned. The other thing was that a lot of them did not share his political views. To put it mildly. In fact, in the thirties, a lot of these people were, if not liberal Democrats, were flat out socialists.

Speaker And somebody supposedly asked Luce once why it was that he, the most Republican man in the country, had all of these left wingers writing for him at Fortune. Why didn’t have more Republicans? And his reply was, Republicans can’t write.

Speaker All right. Sorry. No, that’s fine. I got great.

Speaker I’ll get the kinds of things that thrive. Believe me, if there is picture. OK. At what point did he begin to emerge seriously as a. As a public man in.

Speaker His influence grew steadily, but it reached what you might call critical mass. I would say in the 30s, when he was still quite a lot a young man. But at that point, not only was time well established, but Fortune almost immediately got the attention of the business elite, the movers and shakers, the captains of industry who became very concerned with what might be said about them in Fortune. So he had their full attention. And then life from the beginning was a hit. And so this was this great populist vehicle that eventually became an enormously high circulation magazine. But even in the 30s, put those things together. And he had critical mass at that point. He had. And then, of course, March of time, he was reaching people through the radio and through the movies. He had a critical mass. He was the media mogul above all of that time. And, of course, it only got greater from there on. One of the amazing things about it is that he was able to sustain it for as many decades as he did so that even into the 60s. JFK and Lyndon Johnson were very concerned with what TIME magazine had to say about them. And they paid a lot of attention to Henry Luce because they wanted to make sure that at least they knew him and they would try to influence what was said. But at the very least, they wanted to make sure that they knew this guy and could pick up the phone and call him anytime.

Speaker We’ll see if you know much about the. Whittaker Chambers at times. Yeah. Sort of. And is in communist.

Speaker Yeah, yeah, it did. And again, I don’t know if I have any special or any particular knowledge of it. It was not anything that I ever researched. And so. You know, of course, I’m aware of it as everybody else is, but I.

Speaker Well, I don’t have any special. What about me? I’ll just keep going. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. If they.

Speaker If they’re. With regard to McCart.

Speaker He is famously. Out in front against a car. Right. I’m wondering if you have any insight into that and also how did you react to. Uh, so powerful man.

Speaker Yeah. And again, I’m not sure I have it. OK. Uh, I don’t know. What I know is I don’t have anything special.

Speaker What about the.

Speaker Roll that. I’m thinking more of life and in the future. Yeah.

Speaker Might have played in. Creating.

Speaker Well, we haven’t talked about the American century. Right. Right. And if you want to if you can choose to talk about that, I’d love to hear from you on. What drove him to write that editorial was how that expressed who he was. Right. I just want to I will I don’t want to make sure I get it right.

Speaker The idea of the American century really was as good a way to summarize Luce’s view of the world as could be found. It really all came together in that idea. And that phrase, he adds, I mean, he believed a lot of things. And when he believed, he really believed deeply and he believed absolutely that the American system, the capitalist democratic system was. Undoubtedly, the superior system of organizing a society that existed on Earth. I mean that there was nothing else to come close to it. And he had no doubt about it. And so, of course, he had no hesitation about declaring it. To put this on top of America’s victory in World War Two was to make the case, as far as he was concerned, self-evident to anybody who wanted to look at the facts. The other angle of this, though, that I think is often forgotten. I mean, people see this and they see it as hubristic and jingoistic. And it’s simply the predictable point of view of a very determined Republican free market guy. But there’s another angle that gets overlooked, which is when he said it’s the American century. He wasn’t suggesting that this dominance or preeminence was going to last forever. He was saying, OK, this is the American century. The previous century was not the American century. And implicitly, the next century may not be the American century. He did have a sense of history that was considerable. And I think he understood when he made this argument that, OK, this is our time. It’s our turn. It is clearly here now, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to last forever. And so as clearly, as strongly as he believed in the superiority of the American system. He also had a sense that, you know, well, I hate to say it, but time marches on. Right. Things change. And he didn’t know what was going to happen. And indeed, when he died, it was impossible to predict even then that what would happen economically in Asia and so forth. But he knew early.

Speaker He knew early in his career, of course, based on his childhood, that Asia was going to be important. And he urged Americans to pay attention to Asia long before it was a fashionable thing to do and obviously long before the economic rise of Asia that we’ve seen in the past 20 or 30 years. So, yes, the American century was the 20th century.

Speaker But he did seem to understand that might not apply to the 21st. Was there a way in which he.

Speaker Used his influence, his magazines, his magazines to propagate this notion.

Speaker Sure. Absolutely. I mean, the idea that America was preeminent and the democratic capitalism was superior was almost implicit in what he did in these magazines. I mean, Life magazine, whenever it looked at life in a small town or whatever angle of American the American experience, it chose to look at whatever it did this it was, in effect, celebrating the American system.

Speaker And, you know, it had critical articles. It had articles that pointed out problems in the American system. It had editorials life did, even though time did not. That would criticize the government. That’s sort of beside the point. The whole idea conveyed in this magazine was that the American system was a wonderful system and that came through week after week. And it has to be remembered also that Life magazine had an influence that is hard for us to imagine. At its peak, it had a circulation of seven and a half million. I’m sorry. You know what that is? That’s my fault. That’s my phone. And I shut it. I turned it down. I turned it off. But it gives you. That was finishing a point about.

Speaker And any time. OK.

Speaker We do tend to forget the influence that Life magazine had, because at its peak it had a circulation of seven and a half million. In a country with maybe half as many people as the country has today. So some huge proportion of households in America were getting this magazine. So whatever vision Luce conveyed there was being absorbed and consumed by a very large proportion of the population.

Speaker Now we’re going into another sort of specific point, sort of his personal political history. I don’t know if you can talk about which is.

Speaker The. Sort of the internal brouhaha over Eisenhower and Stevenson that I think is bad. I don’t think so. You can talk about this.

Speaker Is it possible for you to describe what, again, during his tenure, long tenure? The corporate culture or the the ambience over time? This is. Yes, yes, absolutely.

Speaker Time and Time Inc developed really one of the strongest corporate cultures in America. I think based on what I’ve seen looking at companies of all kinds over many, many years, it had a very powerful culture. And it was built, of course, from Luce and Hayden and Larssen and those who at the very beginning start of this. And it was a culture that was mainly. Eastern, good colleges. Yale was an important part of it, even though not everybody went to Yale. There were a few other Eastern colleges that were heavily represented in the culture, but also because it was a small company for many years, even after that time. And then fortune and then life were established, was still not a huge company. It had a strong personal aspect. It sounds corny, but I think it’s accurate to say a family aspect that persisted for many, many years and for a long time. If you worked for that company and you had a baby or your wife had a baby, you got a little silver box or a silver spoon from Tiffany engraved to you from loose. It was the kind of thing that was just done. There was also a culture of. Sort of taking it easy, I mean, these people worked hard on closing night, they would work all night long. Two nights in a row when it was time to close the magazine. At other times, though, they wanted to show, as a lot of people did, that they know they didn’t have to work too hard. You know that there was a civilized aspect to this. And then another angle, which was on the editorial side was the sort of political part of the culture, because, of course, this was a magazine that had strong. These were magazines that had strong political views that came from the proprietor, a private company. It was Luce’s company for many, many years, for most of its existence while he was alive. And so there was often a sort of tension under the surface because many of the writers didn’t share the views of Lewis. They weren’t Republicans. They didn’t believe the same things he did. But. Nonetheless, their copy was often made to read as if they did. It provided, as I say, tension under the surface, obviously. It didn’t stop the gears. Things continued. The magazine’s got put out. But it was always there.

Speaker Well, if these folks were getting rewritten to a degree where it may not reflect what. What their positions were. Mm hmm. Why did they.

Speaker Why did they stay is a very good question. And the answer is it was a fantastic place to work in most respects. Archibald MacLeish related the story that when he went to work for Fortune in the early days, he was really trying to complete an epic poem that he was working on, except that you can’t really support a family by working on an epic poem. And so he was told that he could work at Fortune for as many months of the year as he felt he needed to. And then he could quit and go work on his poem for a bit when he wanted to do that, which he did. And he said in later years that he has never encountered a more generous attitude toward work than the one he encountered when he worked at Fortune. He couldn’t imagine that relationship any place else. In general, Time Inc, especially under loose, took very, very good care of its people. It paid them well. The expense accounts were liberal. When you did, your work was none of their concern, as long as you’ve got it done well and on time. It was a wonderful place to work and so people could, you know, bite their tongues and withstand a fair amount of rewriting. To get that kind of atmosphere. There’s one other angle that I should mention, which is that for many years, of course, nothing in the magazines was signed. Again, we find this hard to realize today when everything is signed. But in those days, articles in magazines typically were not signed. There was no byline. It was simply the voice of the magazine speaking to the reader. And so writers could write something and an editor could rewrite it heavily. But the writer didn’t feel that he was being personally misrepresented to the public because the public never knew who wrote it anyway. So it did may make the burden a little easier to bear.

Speaker It’s interesting, you know, I’ve worked on films where, you know, I’ve been upset that I wasn’t. But TV networks.

Speaker It wasn’t given credit at the end. Yeah. And then I realized the upside.

Speaker That’s right. That’s right. It isn’t all bad. That’s right. But it’s amazing when you think back. I mean that there were these Peach’s pieces by Archibald MacLeish and James Agee and, you know, people who became very famous writers appearing in Fortune.

Speaker But no one ever knew it. None of the people, none of the pieces had a byline. And similarly, in time.

Speaker We’ve got moves and timing with regard to.

Speaker I don’t think I can. I wish I could. Uh. I don’t know. Let me ask you this. What point do you think? Lose, reach the. The scene of his.

Speaker I think the zenith of Luce’s influence was probably. Fairly near the end of his life, early 60s is my guess, early 60s, mid 60s at that time. The number of mass media outlets in America was still fairly small. There were the three major television networks and only two of them were really significant. CBS and NBC, there was time, there was Newsweek, although at the Time, Time magazine had a huge lead over Newsweek in circulation and influence. The idea of a national newspaper like The New York Times is essentially today or USA Today simply didn’t exist at all. And so he had a very powerful position. There simply weren’t that many ways that all of America was consuming the same message. And he controlled.

Speaker Time and life and then fortune as well.

Speaker But the mass media vehicles were time in life. And so that gave him a huge amount of influence. I don’t believe the circulations of those magazines were ever higher than they were in those years. That was their zenith as far as Reach was concerned, especially reach as a percentage of the population. And of course, there was this very contentious issue, which was the war in Vietnam and how time and life felt about that war was enormously important to the administration.

Speaker Right. OK. OK. Do you remember what your life did?

Speaker One week’s dead in think.

Speaker Actually, just like whole thing. No. Perfect. All right, I just wanted to see what was behind you. Yeah, but no, I know. Okay. Yes.

Speaker Well, of course, for the first many years of Vietnam, the publications time and life were clearly supporters of the war. And again, it wasn’t necessary for anyone to say in the magazine explicitly that they favored the war. It was just clear from the way it was being covered, the way it was being written about that it was the policy of the magazines, which meant the policy of loose to favor it. And that policy did change. And it famously changed near the end of the war, where both time and life became clearly opposed to the war. And I think you have to conclude that it had a lot to do with Luce’s death when he died in 67. A lot of the resoluteness of the company’s position began to fade away. And the fact was you had a lot of people on the staffs of these magazines who were opposed to the war, and their voice simply couldn’t be heard as long as the official policy was otherwise. But the tide of opinion there. The pressure of their opinion eventually became overwhelming and the Venne management of the magazines came to feel the same way. And so you had a change in the tone of coverage. And of course, ultimately, you had that famous feature in Life magazine called One Week’s Dead in Vietnam, which I suspect did as much as anything to change. The view in Middle America as it came to be called was a time phrase of its own. But in medical. In Middle America to change the view of the Vietnam War.

Speaker Let’s go back. Yeah, a fortune, right?

Speaker Was so loose, came up with this great idea for a Fortune magazine at the height of the bull market of the late 20s made perfect sense. The only problem was that in the time between having the idea and getting the first issue off the press, we had the crash and the economy went from a boom to the beginnings of the Depression. As it happened, in fact, the first announcement of Fortune magazine, the first public announcement of Fortune magazine, appeared in the issue of Time magazine that was out at Black Tuesday itself. And so here in the worst crisis of capitalism of the century, you had this announcement of a new magazine that was going to celebrate capitalism and be all about big business when big business was going right down the drain.

Speaker The incredible saw the first issue of Fortune came out February 1930, the beginning of the Great Depression. No one knew it at the time. And of course, it was either loose or one of his lieutenants who said at the time, let’s be realistic. This economic downturn could last as long as a year. And so they thought, let’s just be prepared for that and we’ll go on anyway. Well, obviously, it lasted for many years. Incredibly enough, though, Fortune magazine launched into the worst imaginable environment. And at a very high price, the most expensive magazine anyone had ever attempted to sell a dollar a copy succeeded and it succeeded as a business, not just as a as an artistic or a journalistic enterprise, although it succeeded in those ways, very notably, but as a business as well, in a world in which a magazine is very lucky to break even in two years. Fortune broke even after its first year going into a depression. It’s an amazing thing.

Speaker Great, great.

Speaker How did.

Speaker Well, let’s let’s talk about Sports Illustrated. Yes, come to create sports.

Speaker I think Luce’s view about Sports Illustrated was that there was a great opportunity here, that there was a market opportunity here in a way similar to what he had done with Fortune, in that there was a lot of interest. There was a niche, a journalistic niche here that wasn’t being filled at all. There was no national magazine of any stature treating sports. And so he, you know, lose personally, didn’t care much about sports, but he saw an opportunity and he was right. And of course, in keeping with the magazines he had started previously, Time and Life and Fortune, he was going to call this one sport. But it turned out somebody somewhere owned that title and they couldn’t get it. And so they called it Sports Illustrated Sports in great big letters and illustrated in little tiny letters underneath. And there it was.

Speaker How is it that a guy who. Really didn’t pay much attention to sports or wasn’t into sports. Had the. Attention or the wherewithal to. Conceive of.

Speaker It’s a good question, that’s why Lucy, who didn’t care about sports, would still come up with the idea for a sports magazine and how he would even know or become convinced that this was a reasonable thing to do. And I think the answer has to do with his genuinely endless curiosity about the world. He didn’t care about sports, particularly personally, but it was something that was happening out there in a big way. And he truly did care. He was interested and curious about anything that was happening out there in a big way. And so he could observe with detachment, but still terrific interest the fact that Americans were utterly devoted to sports. And he figured, well, that makes a lot of sense. There’s an opportunity for a magazine. I should add one other thing, which was that in the early years, Sports Illustrated wasn’t sure what kind of magazine it was supposed to be. It has developed into this magazine all about spectator sports. It’s about football and basketball and baseball and hockey and other things. But the things that we watch on television in the early days didn’t know whether it should be about them or should be about the sports. That people participate on their own should be about hunting and fishing. It had recipes in it in the early days. No one was quite clear on what it was supposed to be. And it’s interesting that it didn’t make money for years. In fact, by one calculation I saw Sports Illustrated didn’t break even for 12 years. Now, that could only happen in timing as a private company if it had been traded publicly on the New York Stock Exchange, as it is today or as it became later. No one would have dared to keep a money losing venture going for 12 years. But when it was a private company, Loose was the proprietor. He could do whatever he wanted. He said, we’re gonna keep it going. I still think there’s an opportunity to.

Speaker So, I mean, I guess you answered the question, but so. He’s not a big sports fan. No. Why did he have such loyalty to this man?

Speaker Why he was willing to keep it going for 12 years of losses is actually a very good question. And I think it’s simply because he had faith that there was somehow a winning formula to be found. I think he had enough. Feel for magazines, which, of course, he ought to at that point, that he knew that somehow there was a winning formula to be found and he was absolutely right. And if he had lived long enough, he would have seen Sports Illustrated become one of the very most profitable magazines of any kind anywhere in the world. It turned into an unbelievable money spinner, which I think he only sensed it could be when he got it started.

Speaker Did he personally spend any hands on time, hands on any of his time, hands on tinkering with it to try to come up with a good question?

Speaker He you know, I don’t really know. He must have. He must have.

Speaker How did the company change when he retired? What did that. How did how did his retirement affect his man?

Speaker His retirement had a sort of gradual effect on the magazines. He was around for a few years, about three years after transferring the editor in chief title to Hedley Donovan. And so there was this period when he was in the background and present, but not literally in the driver’s seat. Headly, of course, was a long time Time Inc man, very well-known and obviously handpicked by loose.

Speaker So there was no abrupt change in philosophy or culture or operations when he had handed things over to Headley. But.

Speaker That the rigid control of the point of view, the absolute dictation, if you will, of what stance the magazines would take on various points, just began to ease up. And again, it didn’t happen abruptly. And it was partly a reflection of the change in the Times as well. It just became harder for anyone to insist that their properties hew to a certain line. The way he did and all media moguls did for a very long time. And so what happened was. Gradually, that faded away, the strict point of view faded away as a business enterprise. The people who were then in charge of managing after loose retired began to look more into diversification.

Speaker They considered the company not so much a personal vehicle of a mission, but rather as a business that they were in charge of managing.

Speaker And so the inevitable changes follow that people looked at things much more on dollars and cents rather than on the basis of what’s the mission? Is it improving the nation? That kind of thing. And that translated into a change in the tenor. The way people talked, the way they felt, and it happened gradually and yet by the. Mid 70s, let’s say, seven or eight years after he died. The change was very marked, very noticeable.

Speaker And when a new generation of management took over in about nineteen eighty, I remember asking them at the time whether they had ever shaken Henry Luce’s hand. And they said, no, never did.

Speaker That was Dick Monroe. Who was became the CEO at that time?

Speaker What do you think his. Contribution is.

Speaker Sir? Yes, ma’am. OK.

Speaker I think Lucy’s contribution to journalism was the creation of a new approach that was, if you will, of responsible mass appeal approach to journalism. It was a combination of something that would appeal to an audience of millions and yet wasn’t egregiously populist or demagogic that treated matters of some intellectual interest and didn’t treat them at the deepest level or in the way that specialist or professional in those areas might treat them. But nonetheless, introduced them to an audience of millions, talked about the most serious issues facing the nation in a serious way. And yet in a way that would appeal to a very large audience. It was a middle approach that is sort of easy to imagine, but very difficult to execute. It consists of a thousand details that have to be gotten just right. And he was able to imagine that such a thing could be done, which really wasn’t being done before he came along. And then to execute it, to actually get those thousand details right. So that this thing worked and worked for many, many decades. And although Life magazine no longer exists. Time magazine is still a big, vital thing. Fortune magazine, big vital thing. Sports Illustrated more successful than ever. Those were the ones that existed when he died. But the the approach has proven that even now, so many years later, it’s still valid.

Speaker Do you think he would have felt that people.

Speaker Well, of course, we all want the thing you can’t help recalling when you think about People magazine is his statement that. Telling stories through people wasn’t something he invented, the Bible invented it and telling stories through people was the essence of what he did most of the time anyway. And so would he have approved of it? Well, I’m not sure he could have seen his way clear to saying that it was going to improve the nation or that it was going to fulfill any part of what he felt was his personal mission.

Speaker On the other hand, I’m sure that he would have appreciated it for what it was and probably would have thought that it was being done very, very well for what it was. And of course, the story in the company is that the idea came from Clare Booth Luce. The idea was suggested by her to Andrew High School, who at the time was chairman of the company.

Speaker This was in the early 70s, and that it was then developed and became what it became, which is the most profitable magazine on planet Earth.

Speaker OK. You. Is there anything we haven’t covered that you think the.

Speaker Let’s see. Well, there was one thing which I’ll just say in appreciating what Luce did. It’s useful to recall that when he started time in the 1920s, starting a magazine that was going to become a mass circulation thing was a very formidable task. And there was this thing called the Saturday Evening Post that existed at the time with a huge circulation. And it had a power that no magazine has today. It was paying P.G. Woodhouse twenty or twenty five thousand dollars for the first serial rights to a Geeves novel. Now, that would be easily four hundred thousand dollars in today’s money. No magazine pays that for anything along those lines today. Yet he was tried. Luce was trying to go up against an empire that was throwing around that kind of money that had that kind of resources at its command. And for him to think that he could do it starting from nothing is fairly remarkable when you think back on it. And it’s probably only because he was so young and inexperienced that he even thought he had a prayer.

Speaker How do you sort of calm that sort of a symbol of prestige was to be of. Let me think about what I’m trying to think without having you try to remember.

Speaker Yeah, I do. I wish I could recall.

Speaker Was there a cachet to being overcome?

Speaker Oh, there was absolutely a cachet to being on the cover of TIME. This was. It’s obviously a very large circulation magazine that tended to put people on the cover and so readers were expecting to see somebody there. And the question was merely who was it going to be? And if you were chosen to be that person, that was. I mean, in the age of television, it’s hard to imagine, but that was fame, national instant fame of a kind that scarcely existed at the time. Other magazines didn’t tend to put living people on the cover. Some of them did. But they didn’t have the freak was they didn’t come out every week and they didn’t have the reach and influence that time developed within a decade of being started.

Speaker And also the cash man. Well, that’s still sort of it’s people’s state is still an event.

Speaker Incredible 1927. So that’s what, 75 years of man of the year and people still, as they call it at the time. And so but people still care about it. Who is going to be Time’s Man of the Year? Or woman or whatever it may be. And I’m sure somebody told you the story about how that came to be, about how Man of the Year came to be the story and the company is that. In 1927. Time had somehow simply missed the story of Lindbergh flying across the Atlantic.

Speaker They paid no attention to it when it actually happened, but Lindbergh then became an instantaneous national hero. They couldn’t do anything about him. That was news related because he’d already flown across the Atlantic. So they came up with this idea of naming a man of the year and that enabled them to put Lindbergh on the cover and write something about him and get some attention for it. That’s how it got started. But then it went on and on and on.