Interviewer: Professor Gerald Early. And like Ken does. Maybe he did this to you. You know, what is baseball, right?

Interviewer: A very broad question. Sometimes people go, oh, my God. How can I answer that question?

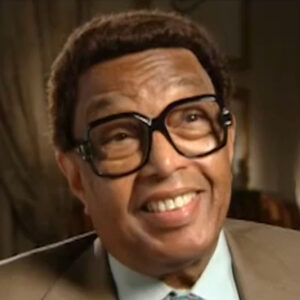

Interviewer: But it’s always interesting to find out what people say to this question is, let’s just settle. Who is Quincy Jones?

Early: Another one that can sometimes turn out that way.

Early: Who is Quincy Jones?

Early: That’s a good question. I think Quincy Jones is the most.

Early: Successful black person in music. Since World War Two.

Early: He.

Early: He’s covered so many bases, however, that it’s very hard to pin him down in one thing or another. And that’s what’s been most extraordinary. He’s been successful as an arranger. He’s been successful as a composer. He’s been successful doing film music. He’s been successful doing pop. He was successful as a jazz artist.

Early: So it’s very hard to pin him down. So in that respect, the only thing you can say is Quincy Jones, successful musician. You say anything else? The other thing about Quincy Jones is that he’s he’s someone who’s had an enormous impact in the culture. And people have heard his name, but they don’t quite know where they’ve heard it or exactly who he is, except they know he’s very successful and he’s famous that he does something with music. I think the most amazing thing about Quincy Jones is that there are very few people in America. Very few people on the planet who haven’t heard some piece of music that he composed, arranged or produced. I mean, his music has been heard by most people on the planet. And that’s quite extraordinary.

Early: He has a dream that that most musicians would would would have is to have lots of people hear their music. Here’s a man who’s had virtually everybody here is music. So Quincy Jones, successful musician.

Interviewer: Great. Let’s just one sec. I just realized I didn’t test my.

Interviewer: We’re back. All right. Great.

Interviewer: So, you know, in your essay, you you look at Quincy and compare him to Miles. Maybe later on we’ll do that. But if you could cut out Miles for the sake of this particular example and look at just Quincy and help us understand how unusual it is for a musician to grow up like learning one language and then speaking in other languages and, you know, handling new kind of artistic expressions that way.

Early: Well, I think what a lot of people don’t understand is that most artists, no matter how great, can be kind of narrow. Once an artist finds a particular way of expression, they sort of stay with that. Musicians are like that to musicians, very much jazz musicians, for instance. They tend to find your sound when they’re pretty young, usually in their 20s. They work out how they’re going to approach music and they pretty much stay that way for the rest of their careers. I mean, they may refine it. They may have different settings, but basically they’re going to be doing what they’ve done when they were young and they’re just gonna continue to do it. Quincy Jones was very different in going out and learning a particular kind of musical language when he was young. Being a jazz musician and also being exposed to rhythm and blues music in his early days when he was with Lionel Hampton and when he was hanging around Ray Charles. But essentially a jazz, a jazz guy and then going into a whole nother realm by doing film music and then going into a whole nother realm by doing pop music and particularly doing pop music, because most serious jazz musicians looked down their noses at pop music and figure it’s awful.

Early: And the fact that he had the courage to do it, I mean, it’s hard to go against your peers. And then he had the courage to do that and that he did it very well.

Early: I mean, that’s the other thing is that most jazz musicians assume that because it’s a simple music, anybody can do it. But this actually, I think he did a good pop music.

Early: It’s very easy to bad pop music. So he got he courage and talent and but he was a very open in ways that lots of musicians aren’t because they’re very focused on how they develop. And not only that, most of them, even if they’re kind of interested in doing something else, they usually either one don’t have the courage to do it or to not have the opportunity to do it. Jones had the courage to do it, and he manufactured the opportunities or were lucky enough to have the opportunities to do it.

Early: And so he’s unique among his generation of jazz musicians who have done what he did.

Interviewer: Speak to, if you would like one of those opportunities, maybe the opportunity to move into pop. I just think for a minute at that moment where he starts, you know what I would say, Lesley Gore? Help us understand how in a way what his genius was, was not to try and reinvent something. You take all those tricks that he learned into.

Early: By the time Quincy Jones had his real first big success with Pop, which was Lesley Gore, I believe the record. It’s my party.

Early: Was this big record. He had become. He was a very experienced record producer. He had done a lot of jazz. He’d also done a lot or in B records. So he knew about the dance beat. He knew about that sort of thing to do a white pop record, as he did with something that was pretty unusual. It would have been probably more expected if he had a big R and B hit as sort of a big white pop hit.

Early: But he knew he was very experienced in the studio. He knew how to put together a sound. And he understood the making of pop music. The making of pop music is the making, as Phil Spector said. It’s not about songwriting. It’s about making a record. It’s about making a particular kind of sound. Berry Gordy understood this very much from Motown. So what you get with a record like it’s my party is sort of genius producing, you know, because you’re getting essentially his putting together various kinds of elements to make this to make this whole record work. It isn’t even necessarily a case of musicians have to play really well on the record. You just have to play effectively on the record for a pop record. A lot of musicians, I understand that they feel as so I have to play virtuosity or something like that. I have to play a virtuoso sound, let’s say, for pop rock. But you have to play with a certain kind of an effect. And Jones understood the nature of creating certain kind of effects to make a really good pop record, which he did with Lesley Gore’s record. And he wasn’t afraid to take the opportunity. I mean, he was he was, you know, had a whole bunch of you know, by this time he’s at Mercury Records. He had a whole bunch of tapes and, you know, decided know, I couldn’t do something with Lesley Gore because she can sing and to a lot of pop singers.

Interviewer: And I just wanted to steal that idea of something I never really thought through. But just coming here, you know, a jazz virtuoso performance, you know, someone who in the studio, in a way, what it used to be was capturing a live event, someone like Sarah Vaughan, who has an expression, a talent that is unbelievable, whereas in pop, maybe, you know, to Quincy’s great success.

Interviewer: That is so much about the producer, not about the talent. Just if you can just make that more concise from within that big audience, right. He’s coming here, the jazz roots and jazz virtuoso Dizzy Solo.

Interviewer: Sarah Vaughan, peace to working with musicians who clearly aren’t as gifted allows Quincy to be perhaps his skills to come to the front.

Early: Well, I think in a in a jazz performance, a record producer is trying to create an atmosphere, especially time by virtue of virtuoso jazz musicians as Sarah Vaughan or Dizzy Gillespie or Charlie Parker. You’re trying to create a condition where these people can go into the studio and perform very well. It’s not necessarily a case as a producer, you’re trying to do any kinds of tricks with anything at all. You’re just trying to set a condition where these people feel sufficiently relaxed. They can perform with a pop record. I think the producer’s going in more or less thinking that the person is dealing with Sinatra or somebody that you’re probably dealing with, someone who doesn’t have a lot, you know, sort of maybe average talent person, maybe slightly above average. And what you’re trying to do is put together a sound by putting together a particular set of elements to make the record work. I think at that point, the producers a sense of how to make the record work comes into play more so than with a jazz musician, where what you’re trying to do is to create a condition where the jazz musicians, personality and power as a performer comes out. It isn’t necessarily a case when you’re dealing with a pop performer that you’re that you’re trying to say the genius of this performer is coming out because the performer may have no genius. And so far as you’re concerned, what you’re trying to do is create a certain kind of sound that can be sold to the public. And that’s an entirely different kind of enterprise. But I would think for a producer, that would be quite a challenge and would be a really fascinating thing to do.

Interviewer: You touched on this a little bit in your first question, but describe Quincy’s connection to African-American music and his ability in a way to leave that behind and go into.

Early: That’s one the incredible things about Quincy Jones is that he basically started out in the world of. African-American music, basically at the time after World War Two, when he was really coming into his own as a musician, really starting out, he wanted to be a musician.

Early: When African-American music is sort of breaking up in the sense that jazz music is no longer dominant and you’re getting another music that’s emerging called rhythm and blues music, and it’s this exciting kind of dance music that’s attracting a lot of a lot of people. But he grew up in this in basically a black musical world, and that’s how he understood the making of music. And the fact that he was able to make a jump clear over to doing white pop music is really quite extraordinary, not only extraordinary for his own vision and his own sense of courage and his own sense of ego, that he somehow can do this. I guess he felt he could do anything at music if he wanted to.

Early: But also once again, because musicians, as I as as I have said, been usually stick with what they have grown up with. And if you are in this particular kind of music, then you’ll stay with that. So that’s a very striking thing about Jones. Is this big? Is this move over? But then again, on the other hand, Jones always seemed to be very open. And when he was young, he played jazz music. He played rhythm and blues music. He always seemed very open to the possibilities of what music could do. Music could be listening. Music could be for dancing. And he seemed very open in that and also because he was an arranger. So as an arranger, of course, he’s looking at music in a broader sense of being a set of textures in this set of effects and how you bring a group of musicians together and so forth. So you have a kind of broader view of music because he was an arranger. And I think that that probably helped him a great deal in being a producer and also in being able to make a transition to not only pop music, but also in doing film music.

Interviewer: What do you think we are the world says about Quincy Jones?

Early: We are the world that’s a very that’s a very interesting record. I think it’s probably one of the most famous. Music sessions in the spirit of music. Whatever one may think of the song. The session has become famous and people have images of the session and the video of it was, of course, a video basically of the session.

Early: That’s that’s quite extraordinary.

Early: I think we are the world was interesting and I think in a number of ways.

Early: I think, one, Quincy Jones was interested in trying to have music, do some kinds of social good.

Early: You’ve had lots of people have done this in the past and he was interested in doing this.

Early: And that’s one of reasons why did the project and so was kind of evidence that here’s a man who has a social consciousness and is concerned about things in the world and so forth, which is all to the good, whether one likes the song or not. I also showed his ability to work with extraordinary range of people. I mean, they were extraordinary people in that studio. Bob Dylan on the one hand, Stevie Wonder on the other. I mean, that’s that’s quite a joke. Bruce Springsteen. So that’s quite a jump of people you have there in the studio. And he was able to work with these people and get them to do what he needed them to do. Quincy Jones seems very, very good at being able to get out of people what they have to offer. And I would think that’s that’s an enormous talent to have if you’re going to be a record producer and to give people a certain sense of confidence and so forth and what they can do and that they can work with other people. And you had to sort of get a sense that they could work with each other and get this project off. So I think in that regard, though, the We are the world session really mythologized him more than anything else is just tremendous pop music maestro who was able to bring these people together?

Early: I think it was an extraordinary moment for him. And I think it was kind of really solidified his reputation as his this

Early: Grand master of pop music.

Interviewer: But speak, if you would. Help yourself to some water. What’s also interesting, you know, is this legendary story. Check your ego at the door. And what I found interesting about your essay, and it’s better in a way not to refer in my essay challenge because. How do we demonstrate? But this idea that, you know, he puts up this sign, check your ego at the door and it’s only someone of supreme ego who could ever do something like that, isn’t it? Tell me tell me how you see. I mean, you talked about the wide variety of musicians and talents, but there’s something else in a room like that that he needed to master.

Early: Well, in order for that, we are the world session was going to get done. But this session was going to work was if all these musicians who are very successful stars in their own right, they sold tons of records, are very successful people in the music business. The only way that’s going to work is if someone’s orchestrating the session.

Early: Who they see as a kind of a maestro figure, somebody who they can very much respect. Most of them, probably all of them knew who he was. And that’s extremely that’s that’s very, very important at this point. And in Quincy Jones, his career, he.

Interviewer: Yes, rain. I didn’t think it right up at this point.

Early: I needed to find the maestro right at this point in Jones’s career. He had worked with some of the biggest names. He had worked with people like Sinatra, Davis. He worked with Sarah Vaughan, who he worked with some of the biggest people in the business.

Early: So a lot of these people are coming in.

Early: They’re they’re sort of been all of him because of the people he’s worked with and this enormous success that he’s had, because this is, after all, post Thriller. And so here is the man who’s produced the single biggest selling album in the world. So at this point, Jones, what I what I think that what I feel this whole session was about was that it was Jones really the exercise of his own ego and being able to corral all these people to do what he wanted them to do and to get this session off the ground. There were I think there are very few people in popular music who could have done that. He was one of the few who could have done something like that. It’s quite an extraordinary testament. Wherever one thinks of the music is quite extraordinary testament of his will. His ego at that session went off to it did.

Interviewer: Right. Are you OK with getting out of.

Interviewer: We can’t them down. You know, I realize I didn’t bring it. I got me into it. I’m really, really sorry. And temper so slight, but.

Interviewer: I don’t know. I’m sorry. That’s good. I would just like that, sir. Come on. Good.

Interviewer: So. So we talked briefly. Let’s start rolling. We are about working across these different fields. And it’s a testament to Quincy’s great skill that he can jump from, say, you know, the music he grew up with to other music. But. The world of jazz didn’t necessarily always prove that you had a great challenge to arrange Dizzy’s tour.

Early: The world of jazz.

Early: It’s like the world of any other music.

Early: If a prominent person leaves that world to do something else, particularly to go after a larger audience, if we’re talking about kind of niche music, people get very upset with. Sam Cooke left gospel to become a rhythm and blues star and a pop star. His fans weren’t just outraged. So how could he do this? So jazz is the same thing in that you go and you become some kind of mainstream success and you’re considered a sellout.

Early: And I think for many jazz people probably do.

Early: I mean, I think on the one hand, they have enormous regard and respect for Jones’s talents, his abilities as an arranger and so forth, and probably are in all of his success. But on the other hand, they probably many of them probably do think he is a sell out.

Early: Nat, you know, he left jazz and went into a music that they have a great deal less regard for. And they probably feel he went into it not because he really loved this music, but because he saw an opportunity to make money. And we live in a world where we have ideas that come from romantic ideas of the 19th century and the 18th century about the artist and this kind of romantic view of the artist and so forth and being true to himself or herself. And when Jones and when Jones did this, people say he couldn’t have done it because he really likes his music. He had to have done this only because he saw an opportunity to make money.

Early: But what’s interesting about Jones is that he had a career that was a mixture of both commercial and non-commercial music. If you look at the film scores that he did in film scores, generally, I mean, there are some exceptions to this.

Early: And of course, you do get films now that just kind of like tracks from or that are designed to be an album.

Early: But basically, when you’re running a pure music film, it’s not really commercial music. I mean, we think about the Pawnbroker soundtrack that he wrote or for the other films in the Here the night or something. That’s not music. He just kind of put on to rely IBSA music that’s written for film. It’s it’s not commercial music and that every site is for commercial product, but it’s not really commercial music as such. And a lot of it is actually when you listen to the pawnbroker or in cold blood or some of the other films that he’s scored, that music is actually very non-commercial music. I mean, it’s very dissonant. It’s very difficult at times to listen to it without the scene that it’s a company. So he kind of he was doing commercial music. But at the end, another round with some music, he’s doing music that is really not commercial, even though it’s for commercial product.

Interviewer: Tie that together to the jazz guy. So, yeah, I mean, look at all the other things, both.

Early: To the jazz community.

Early: He’s on the one hand, there’s certain jealousy, a certain amount jealousy, because here’s a guy who’s gave his music heard by lots and lots of people. I don’t care who what kind of music, whether it’s classical, jazz, country or whatever. The dream that every artist has is that want a lot of people do experience my art. Here’s a guy who’s getting millions of people to listen to his art and with film scoring. I mean, that’s particularly important because he’s getting a lot of he’s he’s able to go in number one and do a lot of film scoring. And it doesn’t have to be. Why use he uses jazz, the fact he doesn’t have to be a jazz film score.

Early: I mean, he he’s doing film music.

Early: And so he’s able to open up his musical palette and do a lot of different kinds of effects and a lot of different kinds of things. You know, he’s able to string several different kinds of things. He needs to make the effects for the film. This is a dream for anybody who’s a who’s an arranger or composer. Doesn’t matter whether you’re a jazz or anything else that you would have this wide palette and you’re able to use a whole bunch of different kinds of effects. So I think to some degree is a certain amount of jealousy. And I think to some degree, it’s a certain amount of pride, too, that he was able to have this kind of success and crossing over to being able to do films.

Early: So I think the jazz community on the whole, with Quincy Jones, I think they’re of a mixed mind.

Early: They’re enormous. I think they would be proud as anybody would be proud in the sense that here is one. He’s one of us. He’s gone down. He’s had this enormous success. I think there’s a certain amount of envy and jealousy and also a certain amount of. Well, he they feel as though he had this success at a certain kind of cost to them in a certain kind of costs.

Early: If you leave aside the film, music for a moment would just look at their pop music with a certain kind of cost. His integrity, by doing the music that they feel is, was how can I put this? Probably a music that they felt was beneath him.

Interviewer: Yes, I’m getting quite a reflection right here. It doesn’t really bother me, but it shows that she wasn’t you know, that window right there is reflected in the frame. I actually for me, it’s good. Okay. Yeah. I mean, it’s up to you. No, no, I. I’m sticking to sticking with .

Interviewer: He’s doing something in a way that.

Interviewer: Really hadn’t been home before, you mentioned, you know, if Ellington had been given the opportunity once he takes the opportunity, makes, you know, if you look at where he’s at now, he doesn’t just make the opportunity. I’ve carved out my little niche. He explodes the opportunity.

Early: The thing about Quincy Jones is that he’s a guy in understanding his success who’s willing to adapt to the situation that he’s in. The idea so far is going into film was not to be a jazz composer for film, but to compose film music.

Early: I can use jazz effects if I want to, but I. But, you know, you listen to a lot of this film music, and it’s within the range of the kind of thing that Henry Mancini and other people, other the other major film scores at the time are doing.

Early: And so that’s one thing to be understood.

Early: This is an amazing adaptability to the situation at hand. He broke down barriers. And another thing to be understood in the film scoring thing is that he’s able to break down barriers and take advantage of his times. The times are changing. Historically, we’re going into the 1960s. And what’s emerging in the 1960s is Jones is coming along at a time, as is the first, really. I mean, you’ve been other black people scored some films. Duke Ellington even scored the film Anatomy of a Murder for Otto Preminger.

Early: But he’s really become the first major black film score. At the same time, we had the first major black Hollywood star with Sidney Poitier, and he scored a lot of Poitier’s films. So it was this door was opening that he kind of walked in and took advantage of Hollywood. Kind of interested in having a black film star or, you know, because we’re in the age of integration in the age of of a civil rights. And he was able to take advantage of that and take advantage of his times. Now, granted that there was a certain kind of tokenism that was going on in Hollywood at this time. OK. We’ll have one black film score, one black Hollywood star. But he was savvy enough to to to take advantage of that and to produce film serious film scores for these serious films that had a very. That were high quality product, had high regard for us for a good part of the time among the black community, as well as a crossover appeal with the white community. Of course, he was also doing white films.

Early: Walk Don’t Run with Carey Grant and The Pawnbroker, and in Cold Blood in other films like this. So the so he was breaking down barriers in in in a number of really important ways and in doing this and taking advantage of his time in a very in very, very striking way.

Early: And certainly what he was doing probably helped open the door for a guy who came along slightly later.

Early: Oliver Nelson, who a black guy who was also started to do film film scores and television scores. And almost certainly what what Jones was doing opened up the door for someone like Oliver Nelson.

Interviewer: Great. Let’s cut. Just one sec. Sure. Can we just boost this to me? I was so struck by those two. Two things. I mean, I just culturally missed the boat.

Interviewer: You are inside. Anyway, let’s talk about him on camera.

Interviewer: Ready?

Interviewer: Well, I think all men dream wrote T.E. Lawrence but not equally. How does that apply? Quincy is such a striking quote.

Interviewer: If you read it. Sure.

Early: T. E. Lawrence, known to the world as Lawrence of Arabia, wrote in his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom All men dream, but not equally. And I think that really applies to someone like Quincy Jones, because Lawrence goes on to say, there are some men who dream their dreams at night and they wake up in the day and realize that they had just been dreaming and advantages vanishes.

Early: But then he said there are other men who dream their dreams in the full light of day and realize your dreams.

Early: That whole cohort of musicians that was that were part of Jones’s generation all dreamed of having enormous success. Some of them did. None had the success that Quincy Jones had. He was a man who dreamed his dreams in daylight and really realized his dreams. So all men do dream, but not equally.

Interviewer: Thank you. Wow. I mean, that part of the essay. I don’t think I’ll ever forget when I read that I was.

Interviewer: Let’s go back to. You know, there were no conservatories. Where one learn black dance music. So as a young kid plays us just again in the time post-war. What did Quincy learn? What talents did he acquire from Motown based group coming through and seeing these these guys, what did they represent to him?

Early: Well, in learning black music after World War Two, jazz, rhythm and blues music, you had to go. It basically was like apprenticeship. You hung around the guys who were professionals at this. You hope they let you sit in, your hope you are going to be at jam sessions. You hope you didn’t embarrass yourself too much and they let you play and you picked up stuff from these guys by sitting in and that kind of thing. And you hope maybe after you got good enough that you might be able to catch on. Now, at this particular time, the most noted black people were black people who were in popular culture. They were athletes or they were musicians. And these people were the heroes of the day. Now, you know, there were, of course, black people who were scholars and black people who did other things. But the most prominent kind of black people at the time were people in popular culture. These musicians were heroes. They were among the few black people who occasionally, from time to time, got written up in the white press. And that’s noteworthy athletes and entertainers.

Early: They were also heroic because they were people who had achieved success prevailing against certain kinds of odds in the culture, racism in the culture at the time, which limit their options a great deal. They were people carry themselves in a certain kind of way. They were admired simply because the way they dress. I mean, they they were dressed very well. They had a certain kind of demeanor. They were cool. They had a certain kind of masculine bravado about themselves.

Early: All this was said, you know, especially to a young boy at this time like Quincy, this would all be very, very impressive.

Early: Lots of people wanted to be musicians because it was a field where, you know, you you were a professional.

Early: I mean, here was the one dramatic way you’re being you’re being shown a group of black men doing something that was very professional, that required a great deal of skill, technical skill to do.

Early: And when you got a certain amount of respect from the mainstream culture for doing it and you were able to carry yourself in a certain kind of way, and all of this, I think, was enormously important to a young guy like Quincy Jones growing up and seeing these guys around him. Clark Terry, Basie and looking at the guys in the band and what they were doing.

Interviewer: I just find it interesting, maybe you have an interesting take on it. In 1951, Quincy takes a scholarship to what we now call the Berklee School of Music.

Early: Didn’t stay long. He didn’t say that, of course, he gets a scholarship to go to what’s now called the Berklee School of Music.

Early: Two years earlier, Miles Davis had gotten a scholarship to go to Juilliard and he didn’t stay either. Basically, he gets to this coast, and that’s really where the conclave of jazz is. I mean, where all the superstars and he wound up doing arrangements for Oscar Pettiford wound up going to New York and meeting people.

Early: And for what he wanted to learn at that particular time, Berklee was not going to help him for what he wanted to learn. I mean, he wanted to be a jazz arranger. This time he thought, this is what I’m going to do. I want to be a jazz arranger.

Early: And if you want to be a jazz arranger you better be around jazz musicians and learn what jazz music is about. He’s not going to learn a lot about jazz music at Berklee.

Early: Berklee is not teaching that subject at the time. He’s gonna learn some kind of important things about harmony and things like that at Berklee. But you could learn that just as well for his needs for doing jazz music. If he’s around jazz musicians and learning from jazz musicians. So naturally.

Early: And plus, these people are as heroes. He had heard about these people, as I heard about Burt Davis and all these people that I go to New York and there they are. You know, the first light of day I see people like Al Hebler, Art Tatum and people like that. Then I just felt I died God to have it.

Interviewer: That’s the that’s when I wished I was in New York.

Interviewer: What about Paris? Paris represents a whole other thing, both, you know.

Interviewer: As a black guy with a white wife and as just it’s a mythic place for American artistic expatriates.

Interviewer: What did Paris mean to Quincy?

Early: Well, I think that when.

Early: Quincy Jones goes to Paris and stays there, he studies composition there.

Early: And so forth.

Early: First of all, I think he really wanted to further develop his skills as an arranger and composer, had learned certain things from jazz, but was actually seeing some some broader things and wanted to be able to do broader things. I think one of the things he mentioned was that he wanted to learn how to work with strings, which is one of the reasons why he was in Paris studying composition. So I can learn how to write for strings. It was assumed by most people at the time that if you were a jazz guy, you a jazz composer. You know how to write for strings. You know, you had somebody else do that. He wanted to learn how to do that. Also, I think it it it opened them up to a to a different situation in dealing with whites because he’s in Paris. And the attitude of whites in Paris is different than the attitude of whites in the United States. Almost certainly, I’m sure he found it easier to have a white wife in Paris and the half point in the United States. And, you know, people’s attitudes basically were more liberal. He also came across a lot of artists and writers. So this just enriched him as an artist. He met people like Richard Wright, James Baldwin, you know, but, you know, there’s a whole big black expatriate community in Paris.

Early: He also met French writers. He met Picasso and other people.

Early: So he got a chance not to become an intellectual, but to be sort of dropped into this kind of intellectual world, into this artistic world.

Early: What makes a great artist is to be inspired and exposed to other great art. And he got a chance to do this. And it certainly had to enrich him as a person, probably made a more sophisticated person, improved his taste. Things of this nature. And it could not do anything but help to make him better at his craft.

Interviewer: What about.

Interviewer: The moment, the pivotal moment where he goes from working jazz, pulling together Clark Terry and the other guys for this free and easy to work to taking a job as a development executive for Mercury Records.

Interviewer: Chart that major moment in his life.

Interviewer: And then again, how he manages to to exploit the opportunity in a way that no one else ever had.

Early: I think the free and easy tour. Free and Easy was a musical by Harold Arlen. It was Quincy Jones was hired to be a musical director. This was a dream he was able to hire.

Early: These musicians that he greatly admired. He’s able to hire Jerome Riches and Clark Terry. So he has this super band that he’s got to go abroad, whether go to the testing out the show and everything in the show fails. And he’s left there with his band. He tries to make a go up and even in jazz friendly Europe.

Early: He’s unable to make a go with the band and the band doesn’t make it. Nat Cole, I think, hired the band for a while, for a time that he was playing over there and so forth. But the band really doesn’t make it. And he came back with enormous debts trying to run this band. And so what happened with Quincy Jones was that he began to run up against certain kinds of commercial realities. And the commercial reality of having this super big band with these tremendous musicians who were unable to make a go of it in Europe. And he came back and had all these debts, probably was one of the things that made him reassess his career and reassess what he could do. And so he wound up becoming an executive at Mercury Records, producing records at Mercury and going into pop music.

Early: One, I’m sure it was just immediate practical need of being able to pay off debt as a result of the failure of the band in Europe. The other, though, was probably a certain level of frustration that. OK, I I’m trying to make music a go here. Professionally, I’m trying to make my living at it. I can’t make a living, at least not very well being able to do jazz music. There are other avenues and maybe I can apply my creative talents and in some other ways. The adjustment that he had to make was that not that he couldn’t still be creative doing pop music. He had to be creative differently. Doing pop music and doing jazz music. Buddy, buddy hit this reality, as I think many jazz musicians did. And people responded to it in a different way. Some decided I’m just going to doggedly still play jazz music to ever diminishing audiences. Others decided I’m going to try to do something else. This was a time of great transition going on in jazz music anyway. You get free jazz starting up now with Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor and people to signing off in that direction. Coltrane later to go off in that direction. You get people deciding you’re going to kind of do a middle ground with Miles Davis. You get soul, jazz and people playing, you know, Jimmy Smith and organ people and things like that kind of playing. So RMV for the Jazz and Jones decides he really wants to get into the business end of music. And I can understand that from someone who’s just suffered a tremendous commercial defeat that he would say, well, let me try to get my mind around what the commercial aspect of making music is. And now Irving Green was very helpful to him, as he has said over and over again.

Early: Mercury Records and and helping him to understand the commercial side of the business, which changed.

Interviewer: OK.

Interviewer: Place Thriller in American cultural history.

Early: Wow. Let me cast my mind back.

Interviewer: You know, you make a point to say that it is significant historically.

Early: Yes, Thriller edis a very important record in American pop music history, it has.

Early: Because Michael Jackson with that and the previous record that he made off the wall.

Early: opened up the pop charts again for black artists, which they hadn’t been as dominant on the pop pop charts before. And actually that kind of opened up a whole new era where you got Lionel Richie and a whole bunch of other people suddenly making the pop charts again. I think that the crossover appeal of Thriller was extremely important in re energizing revitalizing. The idea that black music has enormous crossover appeal. And also, I think Thriller was important because it. Artistically, because Jackson in that album, and I don’t know if it was Quincy Jones, his idea or Jackson’s idea, whatever, absorb not only R&B elements and pop elements, but with tunes like Beat It Even Even appropriated rock.

Early: White Rock elements. And was able to make all of this work. I mean, he was able to absorb, synthesize all these things and make this record. Yeah. He was able to sell this record not only to black and white, but he was able to sell. What was even more powerful about this record was there there was generational. I mean, he was able to sell it to young people, kids, people here. People thought this one, the cutting edge and also the older people who, you know, basically might be listening to James Taylor or Paul Simon is that they who bought this record, as they thought, too, that this was a hip record is everything. When you’re able to do that generationally in pop, that’s it’s just as impressive as if you’re able to do so. There’s both black and white when you’re able to span generations. So I think that in all those ways. Thriller was was a landmark record in being able to do that and being able to set up off the wall. And Thriller being able to set up in the minds of a lot of black performers, how they how they could make a certain kind of sound for the music and how they could marketed and present their music to get on on the pop charts and have a certain kind of crossover power without necessarily losing the idea.

Early: This is cutting edge music or even being seen as as a sell out music. Prince was able to do this, I think.

Early: I think Michael Jackson was a very important example for Prince, and Prince was able to have enormous success after that with Purple Rain and so forth.

Early: So I think it was just an enormously important landmark record. And in other artists, Prince Lionel Richie know the people coming on on afterwork.

Interviewer: Right. What about.

Interviewer: How does the 1991 Montreaux Jazz Festival work? Quincy is working with Miles. Signal an end of a new era in American culture.

Early: Well, and in 1991, Quincy Jones gets together with Miles Davis for this.

Early: Concert in Montreaux. What’s interesting is that Miles Davis is just a few months away from his death.

Early: He’s very sick and.

Early: Quincy is able to get Miles to do something that no one else had been able to get him to do, which was to look backward at some music he had made many years earlier. Davis had always wanted not to do. I mean, Davis, his attitude was, well, you know, sketches of Spain and all that and all that kind of music. He did what, Gil Evans?

Early: He said, why should I do it again? You know, I can’t do it any better. It’s fine to go. I do it again. But Jones was able to get him to do this music again, which is a testament to that regard. Jewish Jones was held by jazz musicians like Davis. And but I think for Jones, it was kind of coming full circle because he was going back doing the kind of charts and things where as when he was a young man, he greatly admired. He greatly admired Davis’s birth of the cool records. Gil Evans and the kinds of things that Gil Evans did and so forth. He greatly admired Gil Evans as an arranger. And so for him, this is going back to sort of his youth in the 50s when he was first getting into arranging and so forth, and he was looking at Gil Evans is this kind of model. He was also looking at Miles Davis is this kind of big hero figure. So it’s it’s kind of going full circle for him. For Miles Davis, this is kind of like a swan song. I mean, he’s able to go back to his big moment. And I mean, really, he made some music that I think no one would question as being great music. When he did these things and he’s able to kind of put this kind of swan song note on his career. But I also think it signifies certainly the end of an era for this particular generation of musicians. Jones and Davis really were part of the same generation that came up after jazz musicians who came up after the war.

Early: And the concert was kind of a signal of the end of that era that this kind of music was not.

Early: This was a signal to me that this kind of music had sort of.

Early: Run its course. It had its day and they were kind of having this last sort of celebratory moment of this music and this scene. The concert seemed more poignant than anything else. And I think it was kind of signaling the end that jazz music wasn’t wasn’t doing that anymore.

Early: It was very nice that Quincy Jones was able to reach to to reestablish a moment in jazz music.

Early: But it was kind of an end for both Jones to be able to do that sort of thing again because he realized that, you know, I’m not going to be able to really do Gil Evans charts anymore something. I got this one moment for Miles Davis to be able to go back to that moment again where he had this really, I think, and unquestioned triumph as a as a trumpet player and as a soloist.

Interviewer: Another big one big question. Throw out.

Interviewer: Is there an opening in a way, how does Quincy embody the American dream? You talked about dreaming daylight and so on, but that wasn’t specific to American sort of. This is tying into ego and things. You can dream it. You can be it. And here we are in Chicago where we’re going to visit his, you know, eating rat. To having your own chef and so to speak, to, you know, in the broadest sense, how he is the archetypal figure for the American Dream.

Interviewer: American dream. All right. Starting in Chicago, ending in.

Interviewer: Hollywood, New York, Paris. Speak to it as you see it.

Interviewer: How do you see that embodiment?

Early: Well, you know, in the United States, we have this thing about the American dream, I don’t know if any other countries have that. There’s a French dream or a Russian dream. But they’re the American dream.

Early: I think Quincy Jones is greatly admired because he embodies that in the sense that what the American dream is a success. Here’s a man who’s had enormous success and he came from nothing.

Early: He didn’t even come from a family that was particularly musical. So this so he has this other appeal of almost sort of being self invented. You know, it’s almost by the exercise of his own will that he wound up doing this this big sum, the self-made man, which makes him even more appealing and fulfilling the American dream. So there is in many respects, Quincy Jones represents the American dream and so far as coming up from nothing, seeming as though he’s his own invention, having success a lot on his own terms and and also being able to penetrate worlds that seem to have been closed off to him. He was able to go over and become a meet record executive with a major white company, won the first black people to do this, able to break into the world of film scoring for Hollywood mainstream film was able to break into the world of Hollywood, not only with with being the musical director for the Oscars back in the early 70s, but eventually becoming a film producer himself. So this two embodies the American dream. But I think it also, particularly in breaking down these doors and going into worlds that were had been closed off and embodies a kind of African-American dream. You know, this idea of you can break down barriers and open up doors.

Early: And I think this makes them in that way, particularly a particular kind of African-American hero that he was able to to do all these things and have this enormous success and the enormous regard and respect from white people that I think that’s very important, that he’s been able to carry himself with a certain way, with a real with a real dignity that people respect. And I think all of that plays into the idea of his being this embodiment of the American dream.

Early: You know, people who believe in the United, you believe more in the power of success that African Americans. Why shouldn’t I? After all, success means a great deal to them. And I think the fact he was an African-American and did everything that he did is is very, very powerful.

Interviewer: This is just tying back to something else he said. Let me just quickly let’s cut from one page.

Interviewer: While pursuing the goal of success. Clearly and breaking down the barriers, that notion of social consciousness.

Early: Where Quincy Jones is a man who has described himself as not being particularly political. Which is true.

Early: I mean, most artists, if you’re concentrating on your art, you don’t have time to sort of, you know, man the ramparts and, you know, go out and lead demonstrations and so forth. But I think he is a man of who’s very concerned about things in the world. And he’s also a man, I think, with real humane feelings. And I think, you know, my own exposure to these. He’s a genuinely caring kind of man. So I think he would be interested in certain kind of social issues. I mean, he come. I mean, he has the soul of a good liberal, which is a good thing. And I think it manifests itself in a number of ways over and over throughout his career. And in 1970, for instance, he was involved with this black music project in Chicago and working with Reverend Jesse Jackson. He had been working a project push almost from its inception, very committed to that.

Early: Further, with a project like We Are the World and raising money for Africa and so forth.

Early: He’s always been a man, I think, who had a certain kind of real commitment to as much as he could, as much as he could understand certain kinds of problems and think about them to want to try to do some good in the world and not just be a success, but to try to do some good, to do well and do good. And I think he’s tried to to do that. And he also seems to be a rather modest man in that he has not gone around and sort of trumpeted doing good things.

Early: He’s also had an impact in and out in another very interesting way in that he’s been a discoverer of of black talent, of enormously important black talent. For instance, when The Color Purple gave us Oprah Winfrey and Whoopi Goldberg became big stars as a result of that film, and they became big stars in the kind of Quincy Jones mode because they became big crossover stars of enormous success as crossover stars.

Early: Will Smith, another person that was basically his discovery, became that kind of star, too. So he’s had that. He’s had a big impact in that way, too, in producing. I don’t know people I don’t want to say in his own image, but having in some way his kind the kind of appeal that he has, that he’s produced these black stars who’ve had enormous megastars and there’s enormous crossover appeal. And I think that’s been very important in that regard with which he is held in the black community of producing these kind of people.

Interviewer: This double check. I’m pretty much done.

Interviewer: You know, I don’t know. I mean, it’s hard for me. I’m we’re going to interview Jeri Jones, his first wife, and talk to Quincy about this. Do you have any take on, you know, this idea that.

Interviewer: He marries a high school sweetheart who happens to be white. What it must have been like at the time and how, you know, in a way that’s reflective of I don’t want to call crossover, you know, sure. That his notion of American culture as being not not color blind, but as embracing. Different. It was, in a way, in the same way the plays, all these different kinds of music. The issue of one’s color and how he.

Interviewer: Respects you or not, is is tied to that kind of doesn’t. It’s not stratified.

Early: Well, Jones, interracial marriages, it seems to me, you know, reveal an interesting aspect of the man and the kind of openness and. Also, because it was difficult to have an interracial marriage, you know, especially with his first marriage in the country, there were still states in this country was illegal at that time, and he got married for four black and white to marry. So, you know, this is significant.

Early: You had an in 1950, 1954, a black guy who was lynched, Emmett Till, in Mississippi, for supposedly whistling or asking a white woman for a date. So it’s this is a very this is an issue that’s very fraught in many ways politically to do this. On the other hand. I think one of these by Jones is able to do it partly, almost certainly is because of his own temperament, who he is as a person, but also because he’s in the entertainment world. He’s in music. And first of all, he’s in jazz music where interracial relationships are not uncommon. And he’s with a fraternity of people who are much more likely to accept it within the larger world of the entertainment that he’s in. It’s also tends to be, on the whole, a more liberal world in a world that’s more willing to accept that. Not to say that everybody in the entertainment world is liberal. Courts course reflect the right people. But generally speaking, people are going to be more accepting of it.

Early: And because he’s in this entertainment artistic world, I think that probably was helpful to him at a certain point in his career in doing this.

Early: But, you know, clearly, he was a man who was who not only was very open to other people, as these marriages would indicate, but also a man who obviously was not afraid, who had a certain amount of courage. I mean, it was to be many people wouldn’t have done something like that. And also a man who to some degree didn’t care what other people were going to think. He didn’t care what white people were going to think about what black people also didn’t like the idea of interracial marriage. I think where they were going to think either he just did what he wanted to do. And I think this is kind of indicative of his career.

Interviewer: Right. Right. The. Final question for you. Any time you’re dying. Yes. Yeah.

Interviewer: So what do you think sets him apart musically from somebody like Herbie Hancock in terms of his success? I mean, why why does somebody like Oliver Nelson or Herbie Hancock or any number of other people, why don’t they have success of somebody like.

Interviewer: Again, it’s.

Interviewer: Well, you know, the tape they had, yeah, there is a certain speak to me. Oh, OK. Let’s talk about that.

Early: Quincy Jones told me once that he was he, by the early 60s, had become very interested in wanting to have a crossover hit. And he said he was talking once with Cannonball Aioli and Herbie Hancock, and they all kind of made a pact that they were going to each have a crossover hit.

Early: And Hancock did it. It was the first to go with watermelon man. And then he said, I did it when I had walking in space. And then Cannonball, I did it when he did Mercy, Mercy, Mercy. So we often filled it by 1970 or 71. We all fulfilled it by having a crossover hit under our own name. So I’d mentioned that only to say that success was very important to him.

Early: But even for a time having success, despite the fact that even at this time he was in the pop world, having being able to have a certain kind of commercial success with jazz was very important because walking in spaces is basically a jazz record.

Early: And I think that’s that’s important in trying to understand the man and that he has been interested in his career, in the potentialities of jazz as a as a commercial music.

Speaker Here’s the reason why he’s had a certain kind of success, that it exceeds someone like Herbie Hancock or Oliver Nelson or people like who also were in fact quite successful and have been quite successful. But his success goes beyond what they’ve been able to do.

Early: It’s probably because, one, Quincy Jones seems to have an unbelievable work ethic. I mean, I think he’s been a man who has probably not slept in 10 years or 20 years. I mean, enormous work ethic. He put out hundreds of records and he produced hundreds of records. He was producing records. He was also writing films. And he was doing all this other stuff. And so I think just the scope of the work he was doing was larger than the scope of what some other people were doing. He had just had an enormous work ethic. I think it’s like in pro football, the adage is you can beat your opponent if you outwork them, test the kitchen table.

Early: He’d be all of his opponents because the heat just about worked everyone.

Early: And he had and I think it has a lot to do with the range of work he was willing to do and the fact he was willing to also work so much on the producing end and the business end of the music, which lots of other people are are not willing to do or feel uncomfortable doing or don’t feel they’re capable of doing. Many jazz musicians feel that way. Miles Davis was never one who ever produced his own records or ever felt comfortable with the business end of the business.

Early: I mean, there are lots of musicians who are like that. And Davis I mean, Quincy Jones was able to conquer that, whatever kind of fear he might have had of that and really be able to succeed in a large way in the business into the music, which I think accounts for the tremendous range of success.

Interviewer: I got the last question, what’s his most important legacy?

Interviewer: Is it Thriller or is this or is it as as a mogul as he is sort of this highly respected black entertainment mogul who, you know, continues to do interesting creative stuff? I don’t know what. What’s your take on that?

Early: He probably will be will be remembered as a mogul, as this guy who kind of.

Early: We could talk about the world of Quincy or the world of Quincy Jones.

Early: And he will probably be remembered in that way as a guy who did all this sort of stuff really well.

Early: He had this great range of music. But as a kind of.

Early: Inspiration. So although this is inspiration to somebody like me, what I get out of it is to not be afraid. Two, to do things and to go out of yourselves. Of yourself as an artist and to test yourself. And also to understand the commercial and business end of the art that you’re in.

Early: I think that he’s an enormously important example in that regard, that every artist should have a picture of him on his or her wall, said, yes, understand the business aspect of your art, the commercial aspect of your art. I think that’s enormously important. And I think for me personally, it’s that’s how he’s an inspiration for me and not to be afraid to do something because you’ve never done it. And to have the confidence in your abilities to be able to do something that you haven’t done before.

Interviewer: It’s one last thing. I’m just curious about who were the people in terms of entertainment and business. Things like that, who mentored him because he’s been a mentor to so many. Sure. Music. Who were the people that you think? Sorting through all this is the last 20 years. Yeah, it’s one of the most powerful producers.

Early: Oh, right. He’s had a range of mentors. And I think what’s interesting about Quincy Jones is the range of mentors that he’s had. He’s he’s a man who’s not afraid to have mentors, and he’s a man who’s not afraid to to to have people help him.

Early: But I mean, if you want that, you know, musically, of course, he started out very influenced by Ray Ray Charles when they were both kids. He admired Ray Charles from the beginning and Hampton, of course.

Early: And and which really I probably was his was that gnarly exposure to jazz because Hampton’s music was so much rock and roll was in Hampton’s music. I mean, it’s probably was his first exposure to rock and roll was really through Lionel Hampton.

Early: You know, Alan Freed made a movie called Mr. Rock and Roll, and Lionel Hampton is the star. The movie Lionel Hampton is Mr. Rock and Roll.

Early: So he got the exposure in this in this.

Early: Those were his early heroes as well, to be bop guys and all that, I think. And then he got other people. I think Henry Mancini was a very important influence in mentor form with the with the film scoring. Sidney Lumet, I think, was also very important with him in their early days when he was doing the film scoring just to give me the confidence in the belief that he could do the film scoring. Irving Green, of course, at Mercury Records was very, very important for him in learning the business end of the music.

Early: And that’s what I think Steven Spielberg was very important in giving him.

Early: As he said, he went to the University of Steven Spielberg and so forth.

Early: Filmmaking goes and learning about making film and being a producer because this is something he had never done. I mean, when you’re dealing with a film as a as a film score, you’re getting as a finished product. You’re not there during the whole making of the film. So this was very important to him, too. So he had a stretch of people and different aspects of the business. I mean, that’s what’s really very interesting. You know, people like Macini as a film score, a film director like a woman or a film director like stillbirth or a business guy like Irving Green, somebody like Nadia Boulanger, who taught him composition in France. And he had a bunch of mentors from different aspects of the muse of music. And I think this is what has collectively gone into making what he is.

Interviewer: Right. You’ve got to send you’re on your way and fortunately, you just get like 30 cells, right?

Speaker So, Hayden, you called for.