Speaker Jerome Robbins Broadway came about when Florea Leskie, who was his lawyer and a dear friend of mine, came to see me and Bernie Jacobs and she said Jerry would like to reconstruct his dances in his Broadway shows. He’s not agreeing to have it go to Broadway. Would we finance this without any assurance that it will go any further? We said yes immediately because Jerry Robbins reputation and accomplishments really were outstanding and he went ahead to try to reconstruct his dancers. They were not immediately in his memory, so we had to make arrangements for him to get access to the various tapes that were in the Lincoln Center Library for the performing arts. And of course, we had to get the necessary support people for him and we had to pay for all of this.

Speaker So after about six months or so, we were at the million dollar mark. And he said that he would like to try to go to Broadway.

Speaker So then we entered into another period.

Speaker And in that regard, there were any number of people whose consents would have to be acquired. In order to go ahead, various authors and composers, lyricists and designers.

Speaker Many, many, many people.

Speaker And.

Speaker And not an easy task to accomplish that because his demands were so outrageous.

Speaker As far as compensation was concerned and the antipathy towards him by his collaborators over the years was such that it almost fell apart. But eventually it was Leonard Bernstein who. Who’s responsible for bringing all of them into agreement?

Speaker By saying he’s a genius. And we have to cater to genius. So they did. And the negotiations as far as the others compensations were concerned was very difficult. And as I said, it almost fell apart.

Speaker They were reluctant to work with him in the first place. And they were outraged by his demands. But ultimately, they all agreed. And I went to a meeting with all of them. That was the final meeting. They were going to go, oh, we’re not going to go, and we had 42 creative people represented.

Speaker I think at 14 different agents had to have a formula as their compensation.

Speaker And since he demanded 50 per cent, it was an easy. So cities we go where we don’t.

Speaker So they agree finally and then the rest is a long, long story and I will eventually tell it all, but that’s how it started.

Speaker OK, great. Now, I was reading an article in Variety not long ago celebrating the Shubert Organization’s 100th anniversary. And there’s a quote from you that says about Jerome Robbins Broadway. That was three years of working with one of the most difficult men. Can you explain why you felt that way and give me some examples?

Speaker Well, he was I would call defensively aggressive. And if you approached him, he would be on the attack.

Speaker Whether that was instinctive or whether it was deliberate. I really, really didn’t know.

Speaker But it made access to him very difficult, and you’re not dealing with somebody who is receptive generally to ideas, and you are certainly at least I was very deferential that about suggesting anything because he could take in in one brief look at the stage would be more than probably I could have discerned if I looked at the stage for an hour.

Speaker But.

Speaker I’ll just give you one example. After we had produced Jerome Robbins Broadway and the idea of including his name in the title was his Central. Not only that, the size of his name was this essential. Our partner was Santori, the largest distiller in Japan and a major. Company, they were so intrigued with the idea of doing something with Jerome Robbins, they were our partner on that and many other shows thereafter. So they produced the show in Japan, Milliman picking up the show here and and moving it to Japan. Well, when we got to Japan and by the way, they met all of his demands for housing and transportation and what shows he should see and how much time he would be there and so on with him and a friend that accompanied him. He was invited to go to the home of the chairman of Santori for lunch.

Speaker Well, that’s quite an honor in Japan. And he said to me, I’m not going. So what do you mean you’re not going? They did everything for you. Every wish of yours they accommodated. I’m not going.

Speaker Well, finally, he went. And they gave him a beautiful Japanese framed screen, which touched him enormously. And that was before the show opened. And in relatively short time there after the show opened, but before the opening, he said to me, I’m not going. I said, how could you not go after they did all of these things for you? I’m not going. Well, finally, he went and of course, they were they treated him as if he was a god.

Speaker But.

Speaker He really, he never would acknowledge, express his appreciation. Never did to me the. But that was his nature, but he was once in a lifetime.

Speaker Just one more quote and then we’ll move on, you also said you could never get any satisfaction from that man under any circumstances. So what exactly did you learn from Jerry that you didn’t get?

Speaker Well.

Speaker I just give you one brief example they show.

Speaker That we produced ultimately, Jerry demanded that we give twenty three weeks of rehearsal. Now, 23 weeks of rehearsal is more than three times the ordinary rehearsal period.

Speaker And one day I was visiting some friends out on Long Island and I get a call, Jerry Robbins, how he found me, I really don’t know. But he found me. He said he’d like to see me. And I told Jerry I would come over to his place, he had a very unpretentious place in Bridgehampton. Hardly in keeping with the image of the Hamptons. So he no, no, he insisted that he would come over to where I was staying and he came over, you know, beat up a little car and.

Speaker They never went into the house, it was his own driveway, he said, I have a proposition for you. I said, what is it? He said, I’ll give you back one week of rehearsal if you give me an extra week of previews. Well, I was quick to accept the offer because one week of previews, you have a paid audience and an extra week of rehearsal you don’t. So we did it. But again, he said he never would say thank you. Would never indicate any softening of his personality.

Speaker It was.

Speaker Very cynical attitude on his part. And. I can tell you one anecdote. We had a manager of the show.

Speaker And he referred to Jerry and his work as dancing bits by Rabinowitz, which was his, if you will, born name. Of course, he would never do that in front of Jerry. And Jerry almost drove him to. Well, he did basically do a nervous breakdown. He was relentless.

Speaker And yet. If he told somebody that was good. That was if key to heaven for their.

Speaker Tell me a little bit about the numbers on the show you referred to, there were some weeks, how much did it cost? How many performers were there, if you remember?

Speaker I don’t remember the exact number performed in the show. Cost in the neighborhood of six million dollars in those days was a lot of money and.

Speaker We never we never recoup the investment. The strange thing with these shows, not all of them. But with theater names in shows. Once you get to the Midlands of America. Or even the north and the South names didn’t mean very much.

Speaker And Jerry Robbins was not a name that sold tickets outside of New York, maybe some of the other metropolitan centers, the selection, some of the numbers and the shows were Jerry’s and. Whatever he wanted to do, some of them were quite complicated, some of the scenes, and they were also involved, a tremendous number of cast members.

Speaker He got.

Speaker And.

Speaker Then there was one instance of her. We were opening the show in Los Angeles. And he said he wanted to have the show taped. So we agreed that we would tape that was another contributing cost, and he said he wants to get everybody in the picture. I said, when you do a long shot. They’re going to become very, very small. No, he didn’t want close ups. Well, he got what he asked for, which was a long shot. And then he looked at it, said, terrible, I told you we should have done a close up, you never we never would get any satisfaction. Well, thanks. But at the end of his life, at least with me, he mellowed.

Speaker And.

Speaker The last time I really saw him. Was when there was a benefit performance for Kittyhawk. And I went over and I gave him a greeting and he was very appreciative and I went out to a restaurant for dinner and I was told he was in the restaurant. And he was sitting at a table all by himself, so I went over and I said, would you like me to give you a lift home? He said, Yes. So after we were finished at our table, I went over to tell them we’re leaving and he got up and he shuffled over to our table. He could barely put one foot in front of the other. And I drove him home. That’s the last time I saw him alive.

Speaker But. Never could, really.

Speaker Get close to him. And yet he had some friends. Especially a few women. Who were absolutely. Part of his life and his acolytes bicker Ertegun. And I didn’t know the other woman, Slim Keith. But they were so devoted to him.

Speaker And. But he said he would never.

Speaker He would never. Really express any.

Speaker Warmth.

Speaker Except at the very end, when I met him a few times, he did, but that was a mellowing of age.

Speaker Well, if it was also true, yes, I can actually hear your thumbs.

Speaker I beg your pardon. Sorry. I’m sorry. OK.

Speaker Thank you, Mark. If it was all so unpleasant, why did you put up with it all? Why did you do it?

Speaker Some people who at least in my business who are unpleasant, it’s not worth the time to work with them. Other people who are unpleasant. You make the exception. Because of their. Great talent. Talents and being nice are not handmaidens.

Speaker And.

Speaker I’m sure you’ve heard stories about great entertainers who were miserable people. And if I told you some of the names, you’d be shocked.

Speaker But everybody.

Speaker It’s different, obviously. But some think that they have the right. To demand and receive. So if you want them. You have to tolerate them.

Speaker And. Doesn’t mean you like them.

Speaker But his case. He was he was worth it because he was a once in a lifetime.

Speaker If I’ve gotten this correctly, I think Manny Azenberg was supposed to be involved at some point, but maybe the managing producer or the lead producer, but something happened along the way. What can you tell me about that?

Speaker We would lead producer of the show and Manny was the manager of the show. And I would attribute what I said before about dancing that that was to Manny.

Speaker Oh, Manny, this is just my interpretation, Manny thought that he could ingratiate himself with Jerry.

Speaker Well, he didn’t realize it was an impossible thing to accomplish. And in his efforts, Jerry would become more and more and more demanding. He was relentless and finally, man, he said he couldn’t take it anymore.

Speaker So.

Speaker It was part of Manny’s job to consummate the negotiations with a lot of these individual people. He worked very closely with us in that regard, but he said he simply couldn’t go on. And that meeting that I referred to you referred to, rather, where we settled with the creative people, I took over and handle that.

Speaker But man, just the sight of Jerry. Drove it a year into a state of absolute anxiety.

Speaker So.

Speaker I’m sure many could tell you some stories of his own. But. That technique sometimes would work with people. Who love the adoration or the there’s a couple of expressions for the term up, not for the best for the behavior, really, and it didn’t work with Jerry. And many kept trying to. Overcome it. And every time he tried Jerry, he just rebuffed him. So he. He really wore him down to the point that he had to get distance.

Speaker There were 62 people, I think, in the cast. Can you tell me which, of course, is enormous by any standards on Broadway?

Speaker Can you tell me what you remember about the audition process? How long was it? What do you remember about it? And specifically, do you remember how equity became involved?

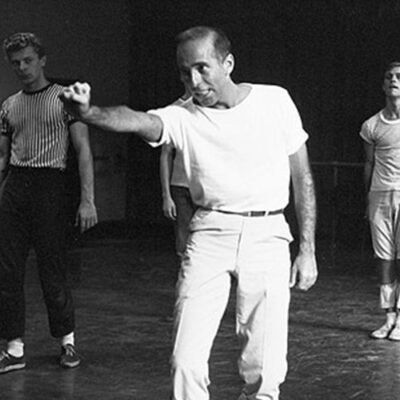

Speaker The audition process, really, Jerry, conducted by himself. He would bring down people who were in his musicals to help him reconstruct the musical numbers that he had created really and.

Speaker I.

Speaker Oh, I really don’t recall. Is having any problems with the union during the run of the show, but. He could drive the cars to tears. Actually, literally. But then if he complimented any one of them, they thought they had praise from Caesar.

Speaker Tell me what you remember about his eyes, spoke a little bit about it before, about how he could see things on the stage. Can you give me an example of that?

Speaker Well, he would just take one. Jerry, Jerry had a perspective that. I never saw an anybody else, even with Michael Bennet, who was a great. Director, choreographer, but Gerry Wood, I’m looking at somebody and peering and looking, Jerry would just turn his head like that. He took in the whole stage. It was simply unbelievable.

Speaker So that was a that to me was a revelation. The people who were in the show.

Speaker We’re all, well, great, great dancers, and obviously with the time that had passed between his last Broadway show, which was Fiddler on the Roof and the time that we did Jerome Robbins Broadway was about 30 years.

Speaker So none of the dancers, of course. Were in the show. And he consulted with some of the. And I think obviously some of his ballets from Broadway are still part of the repertory up at City Ballet, especially the West Side Story. No, so.

Speaker Even though he was a difficult taskmaster.

Speaker I’m sure anybody would say to have a Jerome Robbins show credit on their resumé was worth its weight in gold.

Speaker Tell me a little bit about your impressions of the show. What do you recall? What stood out to you? Why was it important?

Speaker Well, these are some of the shows included, some of the great numbers. In Broadway musicals.

Speaker Peter Pan flying. The bottle dance from Fiddler on the Roof.

Speaker The West Side Story Rumble between the sharks. And I’m trying to think of the name of the other group gents, the Sharks and the Jets. Those were memorable numbers, the mambo number and West Side Story.

Speaker They would they would different. They typify to me the total blend of. Choreography. Acting.

Speaker And storytelling.

Speaker Which is a lot different from the technique. Of. All but very, very few.

Speaker The ballet, no words are spoken.

Speaker And.

Speaker In the theater. And also, by the way, going back, nobody sings in the ballet. So you’re dealing with people who may not be ballet dancers. But have great techniques and all of those three elements and. He certainly found the people.

Speaker Who could do all of those three elements to perfection? He wouldn’t stand for anything that was less than perfection.

Speaker And.

Speaker He was also. So innovative in his creative.

Speaker That.

Speaker You can pick out the very, very few who were.

Speaker Even comparable. I will give you a quote of Michael Bennett, which I think sums it up, Michael Bennett, of course, did Chorus Line in Dreamgirls, and Michael Bennett said to me, I’m the greatest there is. But don’t compare me to Jerome Robbins because he’s in a class by himself.

Speaker Could you talk a little bit about there’s a kind of irony, I think, in built into the idea of Jerome Robbins Broadway in the sense that one of the things that which Jerry excelled in very important in his career was his ability to sort of unify the elements in a show and use them all. You talked about this just a little bit before. Use them all to move the story forward. Nobody ever stopped and sang or stopped and danced. It was all part of a unified whole. And yet in Jerome Robbins Broadway, everything was pulled out of context.

Speaker Jerome Robbins really was sequences from his shows, dance sequences, singing sequences which he selected. And the. To me, that is the essence of his work. Of a choreographer.

Speaker I guess, Agnese, to Milward, the first who really embody that kind of choreography in Oklahoma, but she was not a director. Jerry was the director and the choreographer, and he also, in many instances, was a co writer. He may not have written it, but he certainly inspired the kind of.

Speaker Material that ultimately went into the show, for instance, like the opening night of a funny thing, happened on the way to the forum comedy tonight, he he also and I’m certainly no way an expert on ballet.

Speaker But.

Speaker The range of his different ballis from the comedic to the. Serious ballet.

Speaker It was incredible, but yet he always revered Balanchine as the ultimate master.

Speaker How strong how successful was Jerome Robbins Broadway in terms of critical reception? Also, it’s run.

Speaker It was very well received critically. We had a terrible problem with the show. And how did we could we define what the show was about? He told me that at least 50 percent of the material in the show was new in his segments. Was new, and in order to get it nominated for best musical, we had to demonstrate that. And he wrote a memorandum explaining what originality he introduced to the show. And then, of course, he sequenced the different numbers.

Speaker And determined.

Speaker Long they should be, because we had to have a fixed length time for the show, so and he would have down at the rehearsals various people who were the co creators of the show, like Julie Stein with the Gypsy, No. One than that Fabray.

Speaker He, though. Would spend. Endless hours on his reconstruction of these of these dance’s. So fortunately, there are tapes now and have been for a long time at Lincoln Center. Of the various shows, we have funded most of those tapes and the unions have been very conciliatory in waiving fees.

Speaker But they’re very highly restricted in so far as the U.S. is concerned.

Speaker And.

Speaker So once it was a once in a lifetime scenario, I don’t know of them doing that for anybody else.

Speaker But him. And.

Speaker So despite his being the difficult person that he was. The greats in the theater. Deferred to him.

Speaker Why do you think the show didn’t attract a bigger audience?

Speaker You know, trying to give reasons why shows don’t attract audiences is.

Speaker Very difficult. I think to me.

Speaker And this is just pure speculation on my part. They really didn’t understand what it was. They knew it was not a complete show. In many instances, as I said, they never heard of Jerome Robbins. The reviews were very good. I mean, after all, you can’t. Criticize those excerpts that he created, but. We ourselves didn’t really know how to define it. He didn’t either, by the way.

Speaker And if you’re going to say it’s segments, that’s no good, if you’re going to say it’s not the whole a whole show, that’s not good. If we listed, as we did the names of the shows for which the segments came, that was short changing the whole show. So and again, his insistence on the title we had to have his name simulate the Jay in his name, had to simulate a dancer. Whether we succeeded in that, I don’t know. But since that Jay was so large, it occupied space that might have been available for other ATM advertisements of the show. And of course, later on, he denied that he approved that poster. Right. If anything was wrong.

Speaker He would deny that he agreed to it. So you never really you never won and nothing nothing was restricted or stinted for him, nothing. Even what Santori did for him in Japan. But it didn’t it didn’t evoke. It didn’t evoke appreciation. He wasn’t that kind.

Speaker So basically, it was a marketing problem, you describe it, I think it was I think getting the show to a wider audience was, yes, a marketing problem was also not an easy show to tour.

Speaker We played it in Los Angeles and in Miami. And it was picked up from Los Angeles by Suntory to take the Japan. They. They I think well, since if not more so, about the prestige of presenting a Jerome Robbins experience. And Tokyo and Osaka.

Speaker Osaka, as I learned, and it did very, very well there, but the expenses tended to on the show. Don’t forget, the show had multiple scenes.

Speaker And.

Speaker The cost of putting it on operating, it was very, very expensive. But in a sense, it also was a labor of love.

Speaker If you want a credit about Schubel involvement or for Sherwood’s involvement, which to this day, I’m very proud that we that we did it and I had it all to do over again, I’d do it again.

Speaker You spoke about this slightly, but could you just tell me financially what this meant to the Shubert Organization?

Speaker The show to the Shubert Organization had two characteristics. One was financial, which was not that rewarding, and the other was the prestige of winning a Tony Award for the show of working with him.

Speaker And with some of the best dancers, it’s not the best dancers.

Speaker And singers that did Broadway had to offer and for all of them, including those who would be his detractors. I think it meant the same to them, but on the other hand, it didn’t mean they liked him anymore or any better. But the idea that they worked with somebody like him was memorable.

Speaker Memorable. Just tell me again how much they show me.

Speaker I don’t know, but I think we lost about two million dollars on the show. It was a. Also, I million, actually. Well, it may have been I really would have to check and see exactly how much the show lost for us, but it the loss also was mitigated.

Speaker Because the show played in our theater in New York, so we had income from that source. And in Los Angeles. So if you put all of it into the mix from the investor’s point of view and we were a substantial investor in the show, it was an offset. Those expenses, however, would have been the same for playing anyone’s theater. They presented to the show in their theater, they would have had the same income as we did from that in that regard. So it wasn’t so bad? No, it was not so bad. But as I say, it was a lifetime experience and. Fortunately. We were able to do it if it took place 20 years earlier. It would have been devastating. Put it another way, we would not have had the money to do it. And by 1993, we had succeeded quite well and we were able to afford whatever it cost.

Speaker So I think the show was 89, so Jerome Robbins, Broadway.

Speaker I think so. My recollection is it was later.

Speaker But do you have a theory? Why do you suppose that at the height of his power after fiddler Jerry just walked away from Broadway for a quarter of a century? He said, I’m done.

Speaker Why do you think you did that, Jerry? We walked away from Broadway after Fiddler on the Roof and I pondered asking him why. So after I knew him for quite a while, I said, Why did you ever leave Broadway?

Speaker He answered. No collaborator’s. That was the essence of his for his departure.

Speaker I never asked him that again, and strangely enough, he worked with great collaborators, but I would imagine if he didn’t get his way, he would be impossible.

Speaker It was a tough cookie, so it was all about control with him.

Speaker Yes, and that’s I guess that’s what.

Speaker There’s a reason, and he’s demanding control, alienated others. He was not he was not dealing with ordinary talent. I’m talking about his creators. So they they being sensitive people.

Speaker Resented it. How would you compare, Gerri, to the other great choreographers with whom you’ve worked? You mentioned Bette Farse Champion. Can you compare and how is he differentiate him from all the others?

Speaker He was the epitome of blending. Music. And dance. So that there was total continuity. Of the story through dance. Michael Bennett, achieve that. Many people are very, very good, great choreographers, they’re of a different kind. They have their own distinctive styles. Like Bob Farse. And. Many others were wonderful choreographers. But not often, not often do you have this? Through. Story. Of dance. Coming out of a book seeing. And flowing into another book, see, many times you go to see a musical and, oh, time for the dance number, and they will put in a dance number, which does not necessarily have any contextual relationship to the show. So he was he was unique in that regard.