Interviewer: Well, actually, before you met Alexander Calder,do you remember when you first became aware of what impression was.

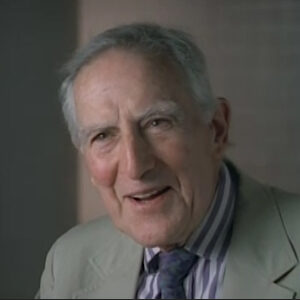

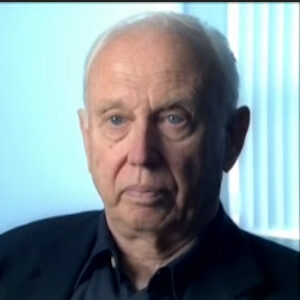

I.M. Pei I was made to be aware of Sandy’s work from way back to his work in Europe actually. His mobile mostly. And then I saw his exhibition at the Whitney. And that was very impressive. The circus group. But I got to know him almost think early 50s through mutual friends like Marcel Broyer, Stillman’s, Osborns. And then eventually the Perls. So we’ve been friends a long time. And I visited him and his wife in Roxbury several times. So even before we worked together, we’ve been friends.

Interviewer: Let’s talk about the man first. What was he like as a person to be around? What was his household like?

I.M. Pei He’s very childlike. Somehow seemed to me like a like a grown up child, a huge version of it.

I.M. Pei And he loved these little things, you know, yet he doesn’t he didn’t talk very much. I still use present tense as if he’s here with me that he didn’t talk very much. But when he did talk was always there’s a whimsy behind it. You can look at his face and you know that he enjoys it, enjoys company, enjoys wine. He’s a guy. He was a very convivial person and a wonderful person to be with. And it says, well, I’m fond of him.

Interviewer: I understand he loved to dance. There was once a story he danced an entire night at a party.

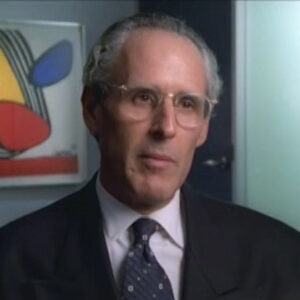

I.M. Pei Yes. Especially if you had a couple of glasses of wine. Yes. Yes. But then many of his close friends are no longer here. You’re fortunate to catch Bob Osborn. That’s very, very close friends. Much closer than I could claim to be. And but my first. Encounter with Sandy as a solid architect artist’s relationship was actually MIT early 1960s. Prior to that is friendship. You know, I was very much familiar with his mobile, as most people were in those days, but I became much more impressed when I saw his first stabile. I thought that his that was important. That was the beginning, at least for me, a possibility of a heck of an association between an architect and an artist. Mobile has limits. Honest, as for me, as effective. If it were large national gallery, I’d come to that later on. And because it moves, so therefore, if you put it in outdoor setting, you have problems. And those problems, technical problems. It was stabile. I think Sandy accomplished something which in which actually enabled him to do things of very large scale and somehow seemed to be appropriate to me. And I became fascinated with his stabile in the 50s and when I had my opportunity to commission him at M.I.T.. I did so. And he made the great sale, you know, right on access from the Charles River all the way into a building they like to sign.

Interviewer: Can you remember back when you were designing, what part of the process did you think of Calder to say, I want to do this. Where were you? Was it the bluenprints? How did that come about?

I.M. Pei If you’re interested in the history of commissioning, is that the biggest? First of all? There’s always a committee, an architect done in those days. I see them now. I would well, look, I want Calder. You know, you don’t do that. You have a committee to talk to a mighty fine arts commission or group of people belong to the Arts Council. And I. I remember. I remember. I think it was. And this president, Stratton and Mrs. Stratton Kay Stratton was very much interested in this. And so as Mr. Mrs. McDermott from Dallas, she, by the way, contribute to really a patron of the arts. And she was that she still is today. And we had a meeting at M.I.T. at the president’s to this house and we came down to three parties. I believe they were David Smith, my first choice, Calder and. We talked to all three of them. But after the conversation with David Smith, we all decided, including myself, that he was not the man. He was not interested in this site. He was not interested in adjusting to the surroundings. He just said, you come to Bolton landing and you pick one. Oh, that’s very difficult. That’s not the kind of thing we want to see. But with Sandy is very different. And he just said, look, you pick me there. So we took him to the site. You look at these are wonderful and the right then and there, we all felt that he was the man and we chose him. And no regret. Absolutely perfect choice. And another thing he did, which I think was quite unusual, I think. And that is he’s so you know, he liked to wear that red flannel shirt. And he was there. It was close to wintertime. He was there making it. The parts would come from grief, foundry or. And he would put it all together. And he loved to show to the students. Now, students would come by and ask, what are you doing? And he was very happy explaining to them. And that was, for me, really the reason why that piece was so well. Because he he was so accessible to the students and the students immediately somehow found that this was the right thing to do. In contrast, we have another experience which Arne Glimcher that we’ll be able to tell you we have of difficulty with the Nevelson. So we commissioned Neverson about five or 10 years later. I forgot exactly now. And it was difficult for this because the students never really did have a chance to talk to Louise. And so I think that was a very you asked me about Calder. Calder has a kind of personality that makes people feel very, very comfortable with him. And there’s a great artist that’s something that’s unusual.

Interviewer: Did you have many, many maquettes? This will be a piece of you. Was there a process of creating it for MIT?

I.M. Pei There was there was I think the committee commissioned him to make the first maquette. And I think he made two maquettes. One is a small one, which he made himself. And that was accepted. And then he made one that is probably six or seven feet high. And that’s in the collection of M.I.T., I guess. And then finally, the big one, the big sale, which I think is about 15 feet high and it’s still there. No graffiti, absolutely free of graffiti. Students love it. And that was my first encounter professionally with Sandy. It was very satisfying.

Interviewer: How did you work with him? What was that relationship like?

I.M. Pei Oh, well, that’s not as easy, really, because he he has a sense of of architectural scale. He looks at it. He looked at the space. Look at the buildings surrounding the space. And the summer intuitively said the piece should be such a just size. And I had no difficulty with that. In fact, I find I found it very much in in in this same kind of order of agreement saying, yes, this peace has to be big. Has to be this size in order to comen the situation. No, he has a very fine sense of architecture and and the totality of the scale of spaces and the buildings.

Interviewer: One short question. Let’s cut for a second. Changing. How did what was going on in architecture time and how did Sandy Calder fit into that?

I.M. Pei I think the European influence on American architecture became quite pronounced in the 30s with the arrival of Gropius and Broyer and then Le Corbusier in his writings, American architecture was undergoing a very, very abrupt change at that time. And Calder Sandy. He himself is half part European. There’s no doubt about that. Fitted in perfectly. And he was very at home with it. And his work seemed to fit in very well with the then architectural developments in United States and many of his.

Interviewer: Now, test, test yes. OK. I just turned you down so that you, as you were very well. Calde didn’t receive monumental commissions until the 50s. What was just described, architecture in the United States at that time. Calders, why was Calder the number one choice?

I.M. Pei He wasn’t the number one choice in the early 50s because people still associated his work with mobile and mobile is not something that you on the outdoors. As I said earlier, that you’d want to make very large sizes because of the movement problem, wind, storm and all that. It wasn’t until he started to do more and more stabile that he became an artist of choice. And that’s why M.I.T.. We didn’t expect him to do a mobile. And we thought that his stabile would be much more appropriate. And he agreed and he did exactly that. And not until a national gallery that actually we tried to mobile, but then it’s indoor, you see, and we could do things in those that that we couldn’t do outdoors.

Interviewer: Let’s talk about the National Gallery. How did that commission come to do a mobile there ?

I.M. Pei Well, before I had two more professional contacts with Calder since MIT. First one at the second one was this one, which did not turn out. Yeah. This is the one. That’s my second attempt. I thought at one time we were doing a large projects somewhere. I forgot where maybe Cleveland, maybe I thought to be wonderful to have a fountain. I remember seeing Calder’s sculpture piece, which was this one with the water coming out of it. I saw in the magazine and I liked him. I said, wouldn’t that be wonderful to have a stabile with water coming out and put it on a reflecting pool? So I went to see Klaus Perls. I said you remember that piece? So of course I do. And I thought, ask him what you think. Do you think Sandy might like the idea of trying it? Yes. I said we’ll be very big. He said the bigger the better. But it then become was not realized because because we couldn’t find the funding for it. Regret. I would have liked to see that one bit. And then came the National Gallery. I recall there was almost a. First choice of all to do a piece here. We had an atrium, a very large atrium, and it did seem to us all to have something up there would be wonderful. Who could do it better then Calder’s mobile indoors. And the space is huge and they can pick a big one. The big Calder, the big mobile, which and we talked to Klaus first and then from Klaus. And we got hold of Sandy. And then we discuss it. And Carter Brown was very much involved in this one. And there was no problem with the with the trustees on this one. They all love Calder’s work. And for once, they all were in agreement that a big mobile will be the right thing to do there. That sounds wonderful, but we had to come back with something that I don’t know. Maybe Carter might have talked about it because he and I are the only two, really that were involved in this problem with Sandy. We went to see this piece. We want to look at the market. He promises it can show you the maquette. I’m having this piece made in Sachè a small village not far from tour where he had a. Some kind of artist studio house. And he took us to the foundry. Not foundry, I think was a boat making place. I think they made both steel things. And we expected go and see a big market of some kind. But no, he already had one piece already finished. We looked at it, Carter, and I looked at it. We said, my God. This is very heavy. Will it move? And we express our concern to Sandy. Right. Then there was one arm, only Sandy, as if this piece is so heavy. Do you think it will move? And he mumbles. It does. It didn’t speak very clearly. They said will move. You know, these are these steel workers. Was very convinced it needed to be that strong because of the length of the arm. But both Carter and I had great reservations. We we express our reservation to Sandy. And since Sandy did not question it himself, we had to leave without any resolution, except both said something had to be done. I can’t imagine. Carter said I cannot imagine this piece of being, you know, with such heavy structure. It just doesn’t look right. And also it won’t move. That’s not the end of the story. Of course, we decided. And I think more Carter Brown more than myself that we’ve got to find someone else to give us an idea as to how to make a mobile looked liked. And he happened to be a, I think, a roommate of Paul Matisse, who is the grandson of Matisse. And he was a really superb designer of. I don’t know what you call it, sort of like structures, and he used airplane construction method to do all those leaves. He did those colorful leaves. They were very heavy in Sachè. The one we saw, each one may wait maybe half a tonne. Can you imagine if you have 20 leaves? It’s a huge scene. So the key and Paul Mattise was absolutely correct about if he can make those leaves light, then everything will become light. And he did just that. He used the airplane wing construction. And today, the was made by Paul Mattise. We were worried about Calder. What would he say when he saw it, you know, and before it was unveiled, he did see it and he mumbled a bit. I think he mumble in the same. Not bad. Maybe he didn’t say so many words, but I think it’s going to be okay. And they I don’t know whether you saw that film we made for National Gallery called The place to be. He dies. Several days, I think several weeks after the opening. And when he walked out, after having seen the place piece in place, walked out very slowly. It was a very poignant moment in that film because he died shortly afterwards. I think he finally agreed that. That’s right. And that’s the only way to make his mobile came true.

Interviewer: Let’s cut for a second.

I.M. Pei Calder the came from a line of artists, sculptors. I think his father made the first made very important piece and in front of a city hall in Philadelphia. I believe that statue is made by Calder’s father. So he came from that tradition. Along with other artists in Europe, he was not the only one, along with many other artists in Europe, they were experimenting on new ideas in a field of sculpture. I don’t include my friend Henry Moore in that category, but I would include people like Picasso, Noguchi. People like that. They were trying. They were experimenting. But I don’t believe they thought in terms of big architectural scale. Not really. I think they were expressing themselves, artistically speaking. It’s sculptural forms and they were experimenting and called as one of the few in the beginning of 20th century that tarted it. But the architectural sculpture came later because the commissioning was not possible, was was not a possibility in those days. But later on, it became one. So several artists started to think in terms of scale, relationship of the sculptural work to the scale of modern buildings ends and Calder’s stabile was very much a result of that. Another person that did something similar is Picasso. You think of Picasso as a sculptor, only doing these wonderful hats and little things that he made and objects to vain, that sort of thing. But actually he was very much concerned about scale of sculpture would in relationship with buildings. His concrete sculpture, of which I had the privilege of having one made for NYU downtown, was very much Picasso’s way of thinking in terms of something that can be enlarged to very big scale. Very, very important.

Interviewer: Well, what do you mean that was known? Coming up, rooms and role when you want.

I.M. Pei To fit in very well with the then architectural developments in United States and many of his architect clients, practitioners, let’s say, modern architecture of that particular period.

Interviewer: OK. We’ll change. And that’s it for wild sound. Back to what we were talking about a minute ago. Can you talk about the transformation from representational art statues to abstract art and Calder’s role in that. Did Calder have part and what we know today is sculpture.

I.M. Pei I think the speaking purely from my perspective as an architect, the commissioning of sculptural objects in architectural setting is a very difficult problem, largely because of scale as our buildings get bigger and bigger. And that’s been the trend ever since the beginning of the 20th century. Sculpture has to scale to size. For me, there’s a limit to how big you can make a human figure. I remember having seen David in Florence, and I was not happy with it. I thought it was too big. It’s a human figure and there’s a limit to how big you can blow up a human figure. It begins to look a bit uncomfortable. So therefore, commissioning a monumental sculpture in the early days is look for heroes. And therefore, you want to commemorate that hero in his image. But because there’s a limit to how big you can make that image. So abstract sculpture came into play. And that, I think, is the key. To Calder and others, including Henry Moore, Henry Moore is always said time and time again as a human being is the beginning of my inspiration. All my pieces reflected true. They are pieces that are much more lifelike than other pieces, and they are pieces because the more lifelike they are more like human figures, the less likely you’ll be successful if you make it very, very big. Now, National Gallery, we commission knife edge, two pieces. There’s nothing you can associate possibly with those two pieces to a human figure and their hands. It could be they make baby and but Calder’s stabile a I think maybe a little bit out of it. Mobile has technical problem, not the scale problem. A technical problem. Sârbu has no limit to scale. Almost no limit to scale. You can make it huge if you want it to because it doesn’t. They do not remind you of a face of a torso or anything of that kind. So abstract sculpture became much more likely to be commission for that kind of architectonic setting. The same goes for Picasso to do that. Sylvette that I commission at NYU. I worried in the beginning a lot about the fact that it’s a face of a lady because it’s so abstract, you know, that it loses that kind of relationship that you find in the. And Benjamin Franklin standing on top of a Collamore or maybe a Augustus on a horse. It’s not that kind of association. It became abstract. Once a month, a piece becomes abstract. There are possibilities of enlargement. So the scale buildings had a lot and scale of spaces have a lot to do with commissioning sculpture as a work.

Interviewer: And do you think Calder had a role in that transformation?

I.M. Pei Definitely.

Interviewer: And what was that?

I.M. Pei Was this just because his work is abstract, abstract and also lend themselves to industrial method of production bronzes, for instance? The bigger they become, more difficult it is. The cast a more costly but steel plates like building a ship has very few limits.

Interviewer: Last question. What? How should we remember Alexander Calder, the artist? What do you think his place in history is?

I.M. Pei I think he truly was and is an artist of his time. He came out of Europe more so than America and his sensibilities, part European, part American. And it fitted in perfectly into the first half of this last century, this century. We’re still talking about this century. And as he developed, his work became more abstract. This is I think at the beginning, there were times when he make circus players, you know, and and figures of people and so on. But that did not last. But his abstract work actually remain. I think the thing that we remember him for his mobile and his stabile. I think very difficult to compare call with other great artists of his time because they’re different. They’re very different. But he one has to look at him and consider him to be one of the major figures of this century.

Interviewer: Do you think that the hardest working abstract sculptures today owe him any kind of debt?

I.M. Pei No, I don’t. Of course, they all make contributions, but there are many others. Many others are doing, particularly sculptors in Europe. They were already experimenting in abstract art. Long before we did. No, I don’t think so. I don’t think he. But his work is unique. Let’s put it this way. But there were others who who made equally important contributions.

Interviewer: Clearly, the last question. It’s been almost 25 years since he died. Do you miss him?

I.M. Pei I miss him very much. Just as a person. As a friend. I would like if he were still alive today, will I have a commission. Well, I think about commissioning him to do a work. Probably so. There are still many possibilities that he had not yet explore with his in his art, which I think we can bring out of him if we had the energy and the time. But time passes us all by. That’s it. One has to think in terms of that and not regret it. Time passes on.

Interviewer: What makes Calder great? What’s so special about his art?

I.M. Pei I think I cannot sit here and say any more than I already have said. You asked me to sum it all up. It would be difficult. I think I’ve said it already. I’m sorry, I think. But I in various ways, I think out of that you can pick things out a bit and make something out.