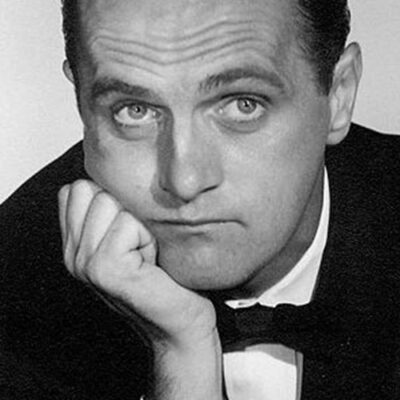

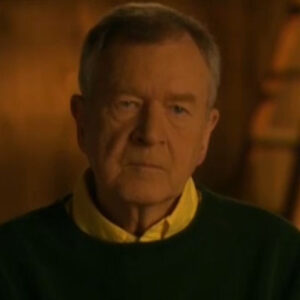

Jack Spatafora: Probably the first time I met Bob was in 1950, and we had grown up in the same neighborhood without even knowing that. But we met at a at audition for a play that I had co-written. It was a musical version of Dracula that’s been common ever since. But in 1950, I don’t think anybody else had thought of a crazy idea like that. And in any event, we wrote the script and we were gonna do it as a local production in Oak Park. And he was going to play the OR he did play Bela the deformed valet to Dracula contractually. And he came out onstage and the first thing he did is walked across the stage, dragging his foot and contorting his face, and he brought the house down. That’s not anything I had written into the script, but that was something that he brought to the script. And maybe that was a sign of things to come. He was just a funny guy.

Interviewer: What was your first impression?

Jack Spatafora: I can tell you my first impression, all of our first impressions of Bob was that he was very quiet and very much like he is today. He seems to he listens and he watches. He’s not a performer, is on a pratfall comedian. You know, like in the old days. And he once told me, I don’t say funny things. I just see the world in funny ways. And that’s what we would notice about Bob. He would go onstage. He was a kind of quiet performer. It was very I guess you would see it to the internal and. But. And a cast parties afterwards. Then he changed it, cast parties. He suddenly broke loose and became very funny. And he did a lot of those routines that became classics on his recordings. But he was.

Interviewer: Everybody settled in. Explain that right, Bob.

Jack Spatafora: We our impression of Bob was when he was on stage. He was good at what he did. But in a modest, low key kind of a way, I mean, occasionally he broke loose on a part. But by and large, he did not dominate the stage. But what was amazing is that consistently after the show, the cast parties, which is what we really look forward to as the cast parties ready. Then he emerged. He was so funny. He was in his own quiet way. He was doing all these routines then that he now is made famous, you know, on his recordings or in his concerts. And we would sit back and we would laugh and we would say, this is hysterical. Bob, why can’t you project this onstage? And he just shrugs. And I don’t know. This is who I am onstage and this is why I’m offstage. But what was interesting is the confluence between his style, which was very intimate and the way in which comedy began to change in the 50s. And they began to look for intimate comedy, not the Milton Berle and Red Skelton pratfall comedy. So Bob came along at the right time and he clicked.

Interviewer: So what did most of you think of me at that time, would you have ever thought he would turn into a performer, a standup comedian?

Jack Spatafora: We all thought that Bob was. Well, first of all, all of us at that time, this theater group, the Oak Park Playhouse, we all began to pair off. It was almost incestuous. There were nine marriages that came out of this group. We had we did 12 plays in three years and we had nine marriages with 45 children. So it’s I don’t know how to explain that. But of all of us, Bob was the only one who wasn’t pairing off. He wasn’t dating. He wasn’t planning to get married. He did have this in the back of his mind dream about becoming an actor or a writer. I shouldn’t say an actor who really wanted to be a writer first. The performance came later. So we thought in effect, in a sense, we said, well, gee, poor Bob is just going to kind of drift along and he’s not going to fulfill what everybody in the 50s in America thought is what you did to fulfill your life, get married, have children, and you can get a home in the suburbs. He stuck it out. He kept fooling around with, you know, comedy routines, this, that and the other thing. And eventually certain breaks happened. But we thought of Bob as being a funny guy whose future was a little foggy. And indeed, we promised ourselves to be very, very wrong. You know?

Interviewer: What do you think he felt when you talked about did he seem as worried as some of his friends?

Jack Spatafora: I think Bob probably was I I I’ve heard Bob say on various occasions that I was a little concerned about where my life was going, he said. And I looked at all of you and things were happening. Nothing was happening to me. And I think he was a little concerned. But, you know, artists. And Bob is an artist. They they do go out. It’s cliche to say it, but they do move to different drumbeats. And he was hearing something different than we were. And I guess he felt, I’ve got to follow that that rhythm. And so he he went in other directions and it was entirely possible that he would have just flopped. Nothing would have happened. But in his case, he sort of stuck it out and then certain things came along, breaks and so on. And it did happen. But a lot of there was there was a period of time in which most of us kind of lost track of Bob after the group broke up. And we were busy raising families and Bob was busy writing scripts and looking for four jobs. And then eventually about the mid 50s. Bob certainly began to emerge in local comedy scenes. And, you know, the story goes from there.

Interviewer: So if you could just explain that. I was hoping to hear from Jack because. I think back. We need to. So, unfortunately, repeat a little bit again.

Jack Spatafora: Sure.

Interviewer: Sorry, sorry about that. Flat. So maybe you could just go back to what you were talking about. Whether or not he felt that he had a future or not.

Jack Spatafora: Yeah, well, in the 50s, the goal of most young people, I think, was what most of the theater group felt at the time. As you get married and you have a family and then you if you can move to the suburbs, you do that and you do all those typical things that went with the 50s. Bob didn’t go in those directions. He wasn’t dating. He didn’t have a marriage in mind. And so, in a way, after the theater group, the Oak Park Playhouse broke up, we all want our own suburban ways. And Bob kind of went his ways in looking for local gigs in town that involved comedy because he was pursuing this sort of a foggy dream that he could get in the show business. And for a while, for a couple of years there, we had lost track of Bob and he lost track of us. But I guess what happened is while we were busy, you know, following the traditional American dream, he was following a dream that he was on a carve out for himself. And so we became typical and he became a legend. And that’s the difference.

Interviewer: So he didn’t express at the time to like, do you think I’m doing the right thing or.

Jack Spatafora: But in terms of how Bob felt at that time and how he interacted with us about his future career, we had a habit and I we had a little apartment in Elmwood Park. And every Friday night or just about every Friday night, we would have a little poker game. It was nickel dime. And Bob would come over and he was a very good poker player. Again, you talk about a poker face. Well, he had it and he has it. And that’s that’s good for cards and it’s good for comedy. But he is at these games a lot of times he would talk a little bit about, whereas life was going and so on. And I don’t know, I always had a feeling this is just a personal sense, that there was a kind of sadness, a Buster Keaton quality to his face and to his feelings. And I think as I’ve heard him talk since, that’s because he was in a sense of drift. But he never apparently lost sight of what he wanted to do. And I guess this is an example of a person who, if you stick to it, it can happen now. Doesn’t always happen. But in his case, it happened.

Interviewer: He didn’t confide in you that he was worried?

Jack Spatafora: No, I don’t think I can ever say we sat down and had a heart to heart talk about that. Not really.

Interviewer: Do you think I said you bring up something? I was gonna ask you, a lot of comedians, they say you come from pain or anger is right, whatever. And on the surface, Bob, might seem to be the exception to that, but I don’t know if they’re more fair than meets the eye you think.

Jack Spatafora: That’s a good question. Did you know you’re right. That’s the cliche. Comedians come from pain. Bob, if you look at his life on the surface and he had a very nice family life, modest Irish Catholic family, and in the outskirts of Chicago where I lived in Austin, that’s community in Chicago. And nice family, nice siblings and so on. Nice apartment building. I remember it very clearly. So for all intents and purposes, his life, like my life, was very pleasant. But there were things about his life that I’m sure from knowing him, he felt pain. And it was an internal thing. In other words, he never wanted for anything. He never suffered on the east side of New York, like he hear so many of the old comics talking about. But he suffered in the sense that I don’t think he felt very popular. You know, he was a small guy, not not a big athlete. I wasn’t an athlete. So I knew that pain. He knew that pain. He didn’t have girls circling around him in adolescence. That’s a very important thing. He felt that pain and he also felt the pain of his theatrical adventures at that time, weren’t really headlining anybody or anything. So he felt the pain of maybe frustration and failure there. So his pain was a kind of quiet pain, I guess, you know, and. But somehow Bob has been able to, I guess you could say, identify his pain with the average guy out there. And that’s why the average guy, which is most of us, identify with what he talks about.

Interviewer: And what about his his family life? Heard him say that. I don’t know what your memories. About them, that, you know, again, on the surface, everything was fine. But maybe he wasn’t particularly close with his parents. I don’t know what you know.

Jack Spatafora: Well, he. I don’t. In terms of his relationship and his family. I’m not. I can’t speak with any, you know, intimacy about that. But I do know that my impression whenever I would drop by, is that there was a sort of bubble in Chicago. We call it the West Side Iris or the South Side Irish. And Bob’s family was very West Side Irish, and there was a certain quality about it. And it is as he watched his parents. That was that of that genre. And that’s, I guess, good and bad both in so I don’t really know how it affected him. I know his sisters and he were very, very close. And that was a very warm relationship. And I think that’s probably the best part of his family life that I observed with the West Side, Irish in the South Side, Irish while in Chicago. They they are they see each other in very different. I’m no expert. My background is Italian. But the South Side Irish field, I think they think of themselves as being sort of special blue collar White Sox fans that live in a part of Chicago that’s separate from the rest of the city. The West Side Irish, I think they think of themselves as being more lace curtain Irish, a little more upscale and their Cub fans. Now, I’m no sociologist. That’s just an impression that I have. But and I think Bob was in many ways very definitely West Side Irish, of course, so are most of the people in this theatre group. The Oak Park Playhouse took place and took root right in the west side of Chicago. And I would say 90 percent of the group were Irish. I was the token Italian.

Interviewer: So do you think growing up in Chicago influenced, you know, is there a Chicago brand of humor?

Jack Spatafora: Bob’s brand of humor. I have a theory about this idea. I’ve never mentioned it to Bob, but. If you if you look at a map of Chicago. First of all, Chicago is in the midsection of America. So it’s kind of mid America. If you look at Austin, this community on the west side of Chicago, just near Oak Park, that’s sort of in the middle of what we call metropolitan Chicago. I think that Bob, in a sense, grew up in the middle of metropolitan Chicago, which is in the middle of America. And he kind of caught the Mid-America feelings of of his times and of our times. And so I think his brand of humor is very middle America. And I think that’s what he projects when he when he performs. And I think people probably respond to that because I think most people think of themselves as being, you know, kind of mid American and their views and values. So I don’t know. But that’s that would be my guess.

Interviewer: Is there also some Chicago? I don’t know. Healthy skepticism of the world. That kind of. Is part of definitely part of Bob’s humor that he may have got.

Jack Spatafora: Yes, I think there’s a in Chicago in contrast to the coasts. I mean, remember, the West Coast and East Coast are very close to the rest of the world. Midwest is very insular by comparison. And I think it’s almost a cliche to say it, but Midwesterners have a tendency of being a little less impressed with the rest of the world and a little more, you know, self turned and maybe even self-righteous and certainly more skeptical. And, you know, you got to prove to me, like the Missourians will say, you know. And so I think Bob. Yeah, he looked at the world with an artist eyebrow. I mean, I’m not too sure if this is true and that’s true. And so his humor is a little more skeptical. He’s not overwhelmed by the fancy dandy aspects of life. And his humor is, is, is, is you can tell it’s not. I think he would call it sophisticated humor. You would call it down home humor of humor that strikes deep into the heart, into the soul, and it scrapes right down to the bone of life. And so I think that’s part of what makes him such an enormous success. He just never runs out of style.

Interviewer: He talked about his writing process. It sounds like he was always writing material, trying things out.

Jack Spatafora: Yes. He was always writing, was always I was noodling around. I mean, I did the same thing. And so I could identify with his interest in writing. What was interesting. Now, this is a I remember very clearly and I don’t I’m not even sure Bob would remember this, but he would write routines and a lot of these routines. This was before, you know, he got into any kind of professional show business and we would go off to do live shows at local churches or community houses and so on. And I remember one time we went to a woman’s club on the west side of Chicago and he and a couple of his cohorts got into two two outfits and they were gonna be ballet dancers. And the music was the music of the rights of spring. And if you remember the right spring, it’s a very it’s a kind of thing that only ballet dancers can really make any sense out of. And at least Bob was he was the the central figure in these to me, chunky football player types were lifting him up to the music and he was doing certain routines in his material. And so, well, the audience sat there and these women were stunned. They had no idea what was going on. They didn’t know whether cry or laugh. And so they didn’t do either. And I remember. That’s an example of where Bob felt pain when he was all through. He just shook his head and he said, I guess they don’t get it. And I said, no, I guess they don’t. And so he he was off off center in his in his way of looking at the world. And so he would when he would write, he would write that way, he would have come up with these bizarre ideas and but it was always low key. And at that time, audiences thought that if it’s going to be funny, it has to be big. And since it was low key, they didn’t get the idea was meant to be funny.

Interviewer: Let’s talk a little bit more, if you would. We’re talking about the cast party, some of the. Routines he would try out. Can you remember?

Jack Spatafora: Yeah, the cast parties, his. Well, I think I don’t know now Bob might debate this, but there was one of the members of the cast who was to make a living. He was a teacher. I was a teacher at the time during the summer. If you were a teacher, you had to go out and find a job. I remember I got a job as a cab driver. This guy got a driver job as a driving instructor. So he would tell stories about his driving instructor work and Bob. But listen to this. And I’m sure that his driving instructor material that that’s a classic of his drew a laugh from that particular guy’s experiences behind the wheel with, you know, new drivers. He would he would get around about certain things that struck him as being funny and he would throw these things out at the party and he would kind of noodle with them. I remember one time he began a routine. I thought this was great. And he said, you know, I got a new I got a new twist here. And he said a picture, if you would, getting on a plane and you sit down next to you, you see that there’s a person sitting there and it’s Adolf Hitler. And everybody laughed a little. What an incredible premise. So then what he said, I don’t know. He said I was just thinking of the premises, that I got to work on that. And I saw his process was he would get idea. I don’t know if he ever did finish that premise, but. So, you know, like writers, these things come in flashes and then they go and Bob but may not remember this. Bob always wanted to write more than I don’t think he ever had performance in mind. And I think I’ve heard him say when he would write for comedians, he would sometimes submit material. He found out that sometimes they would take his material and call it their own. So, you know, they would they would do they would steal it. Not unknown in that business. And eventually, I think he decided I better do my own because I can’t afford to have my material stolen and not be rewarded for my efforts.

Interviewer: Tell me a little bit if you can explain that both of you were in this Oak Park player theater group and some of the types of shows you would do.

Jack Spatafora: The kind of shows, but also the shows that.

Interviewer: If you can ou just say that, right?

Jack Spatafora: Bob and I were both in this group we call the Oakford playoffs.

Interviewer: One more time.

Jack Spatafora: One more. OK, from 1950 to 1953. Bob and I and about 15 other wonderful people were in a group called the Oak Park Playoffs. And we did four shows a year. And the kind of plays that we did ranged from dramas to musicals and comedies. I remember Bob being in several plays that were, I think, rather successful. He was in the play Pygmalion before it became My Fair Lady. It was Pygmalion and he was alive. Doolittle’s father. Great. Kind of a part for him, a comic part. Later on, he was in a play called First Lady, and he was he played a political figure, also kind of a comedic role. He did that wonderfully. Then there was heat. We did The Wizard of Oz. And in The Wizard of Oz, he he was one of the guards outside the Palace of the Great Wizard. And that’s a great shot of him, that him in a guard uniform and so on. And he played. He mugged it, bugged his way all throughout the party. So in other words, you couldn’t he couldn’t help himself. He was funny. And he communicated being funny to the audience. He did other parts over the years. And of the 12 shows we did, I think he was probably about half of them. But as I say, in his his best roles were the cast parties after the place.

Interviewer: So if he didn’t really have in mind to be a poor performer, he thought he was going in the writing direction, but he’s not. He must have. Do you think it was somewhere in the back of his mind? Obviously was in a theater group.

Jack Spatafora: That’s true. He he did he. I mean, I guess his idea of interest and his interest in writing and enacted maybe were parallel. He did have some dreams about, I guess, performing. I think, though, that his experience in this group that the Oak Park Playhouse experience for him probably, I’m guessing now suggested to him that acting is not necessarily my gift. And but writing is a lot of times he performed in scripts that he could have done better writing than than the original author. Recently, we’ve all seen him in dramatic roles, you know, like an E.R. and a few other things. I think, Bob, after 50 years, has finally said, gee, I guess I can act as well as be funny. But I think for those 50 years between the Oak Park Playhouse and E.R., I think he decided I should concentrate on being funny, which is his unique gift, I think.

Interviewer: So are you surprised that he did end up being the star of these two television series acting when he can pull that off.

Jack Spatafora: Well, you know, I’ve got to tell you this in terms of the surprise and watching him on some of these series like E.R., I guess I wasn’t entirely surprised because you’ve seen this happen if you look at the great comedians in the past. Milton Berle and George Burns, Jack Benny, these guys all somehow were able to turn their their comedic talents into great dramatic talent. So, Bob, I think, follows in that tradition. But he didn’t do it right away. He had to grow. He had to mature. You know, I think drama comes from life’s experience and so on. And so I just when I saw him, though, when he I was deeply moved and I wrote to him and I said, Bob, that was really outstanding. Of course, I didn’t have to tell him. He, I think, sense that it was. But that was that was the Bob that was inside of him all along. And I think sometimes comedians and tragedian are just flip sides of the same thing. Right. And I think that’s what we saw. Now, I understand that he’s exploring other parts. Desperate Housewives, for example. I don’t know what you’d call that tragedy or comedy. Maybe that’s a mixture of both.

Interviewer: Tell me a little bit about how Ed Gallagher and how that connection and what happened between He and Bob.

Jack Spatafora: Ed Gallagher was interesting, interesting fellow. He was not he did not grow up in the west side of Chicago like all the rest of us did. Ed came, I think, as I recall, from the East Coast. He moved to Chicago. He was an ad in advertising and he was very Madison Avenue type in his in his style. Somehow he bumped into Bob through a mutual friend and he got involved in the theater group. And one thing led to another. And Bob and Ed decided to do some of these radio routines. And it was a Bob and Ray kind of a thing now. Bob and Ray either came just before or just after them. I don’t remember the sequence. But anyway, they took tape recorders and they did these man on the street or telephone exchanges and so on. And then they try to peddle these these materials to the local radio stations or even some of the local TV stations and so on. And they were very, very funny. But the market for that kind of material, I guess, was somewhat limited. So I don’t know how far of that carried him. I think the important part of those routines, though, is what it did is it gave Bob a ladder on which to be seen. He stepped out and people began in seeing and hearing these things. They became, oh, gee, that’s Bob Newhart, who is this guy? And he’s doing some very funny stuff. And that’s how the serendipity begins. One thing led to another to another. And then he began to appear on local TV shows and so on, and eventually opted to go back to the East Coast and return to try advertising. And I know that Bob and I had stayed in touch with each other for years, very close friends eventually and unfortunately died. And. But there that was a chapter in his career, in Bob’s career that really, I think was very important.

Interviewer: And what was the relationship between the two in their routines?

Jack Spatafora: Well, that’s a good question. What was the relationship between Ed and Bob and their routines? I think that Ed was he was a straight man. I guess you’d say. I mean, what else? I mean, you know, Bob is not silly. Bob is almost a straight man. It’s easy. He’s a funny kind of funny man. He’s a straight man. Funny man is what he is, I guess. But in between Ed and Bob, Ed, was that there the guy that would feed him the lines and Bob was the the funny guy.

Interviewer: And you remember those early?

Jack Spatafora: Yes, the routine’s. Well, I can’t remember the exact ones, but the style was was very similar in most of them. Ed would find Bob in some strange, bizarre situation, you know, at a restaurant or on a street parade or in an entry at a reunion, a high school reunion or something like that. And he would begin to explore the situation with Bob. And then Bob’s reactions that would come back were really off the wall. And. But Ed was a great straight man. I mean, in the tradition of straight men, he never broke. And he was always, you know, taking these things and very, very seriously. And but, you know, the comedy was very low key. It was very, very intellectual, really. And at that time, there were other that there was Elaine May and Mike Nichols, of course, who were also into that sort of a thing. And. And Bob and Ed were I think they were as good as Nicholson May and and. That was that’s what happened. They they they they it became part of their bob steppingstone to other things.

Interviewer: And so when when Ed left for New York, what happened to Bob’s material, he had to find a way to recraft?

Jack Spatafora: That’s right. That’s what I suspect. That’s when the telephone came in. You know what? What are simple but yet solid way of handling the other partner. You just pick up a telephone and imagine he’s at the other end. And I think Bob really perfected that concept. He wasn’t maybe the first Shelley Berman had done it. And so on. But Bob Brady perfected it. And the technique was ingenious because he could take you anywhere, any time just by picking up that receiver. I saw Bob recently. He was in Chicago and he was on a concert. Now he’s upgraded his style. Now he uses a cell phone. But it’s still a phone and it’s still, you know, a device that really works very, very well.

Interviewer: Why do you think it works so well for him? It’s so associated with him.

Jack Spatafora: I know the reason the phone works, I think so well from before for Bob is that he if you if you’re an actor and you’re playing off of somebody else who’s live on stage, you really have to be an actor and learn lines and learn cues and so on and so forth. Whereas if you are working on the phone, you can create your own cues. You can create your own dialogue, as it were. And the audience can imagine as you control the dialogue with the other person is saying. So Bob, in a way, doesn’t have to be an actor. He is an actor, but yet he’s not an actor. And so it’s it’s you know, when you’re on stage with somebody else, you’re only part of a chemistry. When Bob’s alone on stage, he’s the whole chemistry. And I think he likes it that way. And it works very well for him that way. So the phone is all he needs.

Interviewer: Now, what about you? Did you see or watch or participate in any of the dance or radio?

Jack Spatafora: Yeah, the dance, Sorkin connection and Bob’s career here in Chicago is an interesting one. My wife and Danny had dated years and years ago. And then one day we were watching television. One of the local stations. And lo and behold, we we run into. I think it was well, maybe it was radio or maybe it was television. I don’t know which, but Danny is doing a man on the street kind of an interview. And Bob suddenly appears and he’s the guy on the street or in the audience or whatever it is. And it was very, very funny. And in this case, you would watch Bob and most people thought, this guy’s for real. He just came off the street. This is no higher comedia. This is no actor. This is the real thing. And of course, Danny played it very straight, too. And their chemistry was was extraordinary. So Ed Gallagher and Danny Sorkin both were steps on the run to even bigger and greater things.

Interviewer: And what do you recall about Coalson? OK, we’re back up riding the. So what? What kinds of you remember some of the kinds of jobs he had while you were doing the.

Jack Spatafora: Yeah, we all have to have jobs of some kind or another during those years and Bob. He did a lot of pickup jobs. He got through school and as I recall, he went to law school for a while. He was had some dreams about becoming a lawyer, but that didn’t prove to be his particular avocation or vocation. He then began to do some work as an accountant. He loves to talk about the stories of the you know, and he did that for a while. And then I don’t know. I think I remember he in the summer sometime to the job sometimes involved anything from. And he I think he worked at a cigar stand at one time just to make ends meet. I know I had to do things like that. We all did. And so he really had a whole collection of little jobs along the way. And that’s part of probably what was either, you could say difficult or challenging for him. He had to say to himself, what am I doing with my life? It’s not going anywhere. And just sitting around writing little funny routines is not a career. But little did he perhaps realize that that was going to mesh together into something magical.

Interviewer: If you can explain too he wasn’t still living at home with his parents.

Jack Spatafora: Yes. Yes. Bobs still living with his parents, which probably might have. Well, I think he’s talked about that, probably contributed to his belief that, well, I’m not going to go anywhere. Here I am. You know, an Irish son, almost 30. I’m still sitting at home, living at my parents place. Everybody else’s having babies and so on and so forth. Little did he know. I got to tell you a little. Did he know that a lot of us with all these babies and diaper rashes and 2:00 feedings, we’re looking at Bob and saying, what a life. He’s free. He is unencumbered. He has no mortgage payments. And so we looked at him and he looked at us and each of us, NDB the other, maybe,.

Interviewer: Do you know, some of those jobs that were sort of a great way for him to find some find comedic material.

Jack Spatafora: Yes, I think the jobs he had brought him into contact with was people. And obviously, people are here. Your basis for for for comedic material. He he was a people watcher. And he he saw some pretty weird people. But here’s the thing, Bob. We all see weird people. It’s the way in which Bob saw the weird and the way in which he translated the weird. And, you know, a lot of us come home and a lot of times people will see enough weird people during their work day and they come home without the migraines. He’d come home with an idea for a full routine. And that’s the difference between, you know, the the the average guy and the comedic genius.

Interviewer: Let’s talk a little bit of the album.

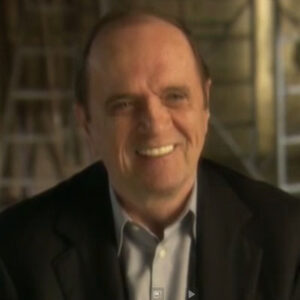

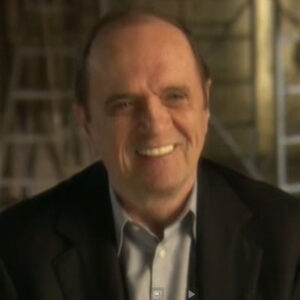

Jack Spatafora: I remember the album, The Button Down Mind of Bob Newhart very clearly can’t put a date on it, but one day it was a summer night and my wife and I were at home and Bob had a habit of periodically dropping by again, not married, no kids. So he would float around among friends. And he came by one night and he had this 33 and a third phonograph record in his hand. No cover, no album, no title. And he said, this is weird. I said, what’s weird? He said, well, he’s a Warner Brothers, just made a recording of what I did at a nightclub in Texas. And at the time, whenever Bob went off to these nightclubs, we always had a habit of sending him a telegram. And wherever he went, we’ve sent him a telegram about what I would say, dear Bob. Be funny. And then we would sign a Jack and Joan. Well, in this case, he was extraordinarily funny. And they caught it on record and he said they think they gave this to me. And this is the master or a copy of the master. He said maybe he’d like to hear it. We said we’d love to hear it. And he played it. And it was, you know, uproarious. It was so hysterically funny. Well, within a couple of weeks, they found a titled The Button Down Mine and so on. And the thing hit the stands and it sold out overnight. And I remember at the time reading this was certainly it was overwhelming for Bob to read. But I was just a friend. I was equally overwhelmed. I was reading things like in some of the columns. Bing Crosby on the set of his latest movie is breaking up. If the cast parties with listening to this guy, Bob Newhart new album called A Buttoned Down Mine and so on. And these stories were coming out about people on the coast all finding and discovering Bob Newhart, who just a few months earlier was just Bob Newhart to us. Now he became Bob Newhart star. So it was an extraordinary experience for us, watching him experience the extraordinary experience of his career.

Interviewer: What did he seem like that night when he came over?

Jack Spatafora: Stunned, I remember very clearly this is one of these little things that sticks in your mind for some strange reason. This is the first time I had ever heard the word weird used in the way he used it. I mean, I know language is a living thing. It changes. But the word weird to me always meant something like a monster and a bizarre experiences. Well, Bob, is he kept saying is he played the album. And we were laughing and so on. He kept saying, it’s weird. It’s really weird. All these things that are happening. Well, but he meant, of course, was what the word now is come to mean. And that is it’s unusual. It’s it’s almost freakish that this is happening to me. And he was right. And then, of course, what happened is that led to other things. And I remember shortly after that album, there was a birthday party for President Truman, who, of course, was out of office by now, and somebody was supposed to be on the stage for that night in the Chicago hotel that was hosting the party. They had to cancel. And somebody who had heard this album called up Bob, and they said, hey, you would be a great fill in. And as I recall, Bob filled in trauma. And a lot of people who were there, they were bowled over by who is this guy, you know? And gradually, this is what was happening over and over again. Different people were hearing Bob Newhart. Bob Newhart. And eventually, of course, bigger people and the networks and in Hollywood began to hear the same thing.

Interviewer: He performed.

Jack Spatafora: As I recall, he performed before President Truman at a birthday party and the Chicago hotel. And, you know, this is, of course, at this time. This is now in the mid 50s. And as these things are beginning to crescendo. Bob, got an agent or the agent got Bob, and this man decided that Bob Newhart was the man he was going to invest his his career in because agents usually they pick some one person that they think are really going to be what they’re going to ride home to. And. And he picked Bob as being the man who was really going to be a talent and a genius. And so, anyway, this this fellow’s name was Tweed Hogan. I think he’s from Chicago. And he and Bob got together and this guy just began opening doors for Bob. And then Bob’s talent just burrow into those doors and things just began to happen so fast, made his head spin. And we were all amazed.

Interviewer: How did his life change suddenly?

Jack Spatafora: Well, you know, he began he still was living at home, as I recall, with mama and papa and his sisters. And at least for a while, he would go on the road. And now more and more, though, for these nightclubs shows. And he said at the time, you know, it’s lonely out there, though. And a lot of us were saying back here, wow, that that’s kind of strange, isn’t it? You’re doing all these exciting things around the country, know what you mean? Lonely as well as lonely. I come back from a big audience reception and I go to the local hotel and I spend the night alone. He said it’s it’s not a very happy existence. And I’ve heard him say since then, when he married Ginny, he’s his comment was, I think of all the years before I married her and had this wonderful home life that I could have had that, but I didn’t. And it was lost years in many ways, because despite the public success, there was a lot of private angst. And so now he’s got it all. He’s got the public and he’s got the private life.

Interviewer: Did you know Ginny or when they met?

Jack Spatafora: All I know. Well, we didn’t know Ginny before he married her, but I guess this is a story goes it was Buddy Hackett who introduced Ginny to Bob or Bob to Ginny. And I do remember this. Don Rickles was, you know, Bob’s dear friend. He was doing a routine one night. And Rickles is is an amazing guy. You never quite know who he is. It’s insulting. Humor sometimes crosses the line and you say always that is he got a little too far. Well, one night there was a show and somehow Bob was in the audience with Ginny. And I remember Rickles that was on television. And it was a moment in which you squinted your toes. Could he start insulting Ginny? And he was saying things about her that most husbands wouldn’t punch another man for, say, about your wife. But Bob sat there because at the time he understood Don was a funny man and was a friend. I’m not too sure everybody in the audience got it, though. It was. But Ginny sat there very nicely, and I guess they’re all very good friends. But that was the first time I saw Bob and Ginny together on television. Interesting night.

Interviewer: Do you know, his success in terms of did he help out the family.

Jack Spatafora: Oh, yes, yes. Bob is very generous, man. And his parents, I don’t know exactly how it all was dispensed. But Bob shared his his success with his family, his mother’s father’s sisters. I mean, they all benefited from it in his extended family, too. I remember about 20 years ago he came back to Chicago for a roast and I was on the dais as a mystery guest. I remember that night. And some of the family members were up there on the dais to talking about his generosity and and so on. And they were very grateful and rightfully so. He’s just a good guy.

Interviewer: How did that album really impact the field of comedy? I mean, it was very different. Suddenly you didn’t really have to go to nightclubs.

Jack Spatafora: Yes, I think the record was a breakthrough record. You know, I don’t think anybody did anything like that before. Since then, yes, more. More and more comics try to make records. Some succeed. Most of them don’t. I’ve heard a lot of them are. They’re the kind of purposeless and silly. But, Bob. Sort of standard. And it’s a standard that, interestingly enough, he keeps meeting every time he’s had a subsequent record. But you’re right about the idea that when you can buy a comedy routine like this on a record, I think the nightclubs suffer proportionately. So maybe audiences are delighted. I imagine some nightclub owners are not. But then again, you see, there is not a lot of nightclubs around the country that people like Bob go to now. Now, what they do is they go to Vegas or maybe they go to Atlantic City. You know what I mean? And so now people travel to the major nightclub rather than the performer traveling to the little nightclubs around the city or around the country. Now, he does do concerts so that, you know, and Bob, as I recall, always said he would much prefer to do a concert rather than a nightclub, because a concert you can do in one or two shops, you do the whole thing and then you can go on home and you don’t have to deal with the kind of Rosty and rowdy elements that you find in, you know, in a nightclub. Bob never enjoyed that. He never enjoyed that at all. However, he was able to stand toe to toe with anybody who would cause trouble on a nightclub. But now I think he enjoys even apparently, you know, he goes to Vegas a couple of times a year and then he goes around the country. And as I say, he was in Chicago just recently, twice and each time he comes. It’s an interesting, multigenerational audience that is learned from young to all day. They really laugh.

Interviewer: Why do you think that is?

Jack Spatafora: His humor is timeless. I don’t quite know why. All I know is I can see it. I mean, I’ve got members of my family. There actually are members of my family older than me. And when they laugh at Bob, I watch. And I it’s interesting because I look at my grandchildren and they laugh, too, because they now see the reruns of some of the old shows. And if I were to analyze it, I guess I would say yes, because there are certain basic. Human elements and all of us. There are certain virtues and vices that we all experience. There’s pride and and there’s sensitivity. There’s embarrassment. There’s paranoia. He explores and exploits all of them. So therefore, if you’re a little kid or if you’re a pig head, you say, oh, yeah, I know how that feels. And he he massages those feelings into what we call routines and when we’re all through. I’ll tell you something else. If I were a comedic historian, I would say what he does is then he purges us of those feelings and those pains. And I guess that’s what the best of all comedians do.

Interviewer: How important is he to Chicago?

Jack Spatafora: Chicago loves Bob Newhart. He’s one of their favorite sons, I guess. Recently, they they built a whole statue, you know, TV land statue. And I must say that my wife and I looked at that and we couldn’t quite believe I mean, our friend Bob Newhart is now having a statue built for him. I mean, that’s kind of extraordinary. And I think he felt the same way. But people in Chicago and certainly city officials and politicians, they love to make use of the fact that this is the city where Bob Newhart came from. It’s better to have Chicago be thought of in terms of Bob Newhart and Michael Jordan than Al Capone were tired of Al Capone. And so, you know, and I remember about 20 years ago, we had a reunion of the Oak Park Playhouse, and Mayor Daley sent us a resolution in which he honored the Oak Park Playhouse reunion and listed all the names. And I remember it opened up with the phrase the Oak Park Playhouse, whose members included the Titanic talents of Bob Newhart. And then the rest of our names were listed immediately thereafter. So, yeah, they everybody in the Chicago kind of likes Bob Newhart.

Interviewer: What do you think? The biggest impact? How does he impact?

Jack Spatafora: He his impact on comedy is, um, I think it’s pretty special, he Bob has, I think, shown by his example that you can be quiet and intimate and honest and still be funny. And as a matter of fact, not still be funny, but that’s the way to be funny. And so many comics today. I can think of a lot of names. They really stretch. They really work so furiously, hard and beside the obvious that the profanity that I think is unnecessary. It’s the the gymnastics and the the cruelty and the anger and the rage and so on. I think it’s also unnecessary, in my opinion, of course, but in a lot of people’s opinion. And Bob has you know, I don’t have to tell you that Bob has never used profanity. He’s never used vulgarity. He’s never used viciousness. He’s never used anger, hatred. His comedy is different. And another there are probably some members of the younger generation will say vile. That’s getting passé. We need more bite to our humor. We need more bite to our drama and so on. Well, maybe they want that bite. But my feeling is, is that it doesn’t help to be chopping away at everything and everything around you. And Bob doesn’t. And that’s why I think he and he is survived.

Interviewer: I mean, his humor is is not to bland. He always had targets.

Jack Spatafora: Oh, yeah, yeah. Well, I’ll take a look at his targets. I mean, he he he he spoofs the baseball route. You know, Abner Doubleday. And he’s laughing a double day, but he’s also laughing not so much at him as the people who were laughing at Doubleday. And so he does it. He does poke at them a poster of the crew of the submarine who have taken advantage of this poor commander who doesn’t know what he’s doing and so on. So, yeah, he has taken a shot. He’s not so bland that he hasn’t got a target. But when you’re all all said and done, I don’t think an audience leaves there the concert or turns off their television set after watching Bob ready to go out and punch somebody. You know, I. This gives me a chance to say what? I don’t know if anybody agrees. I think a lot of people agree. All you have to do is surf on television and you take a look at some of the comics that are performing inch after channel after channel and so on. And I got a feeling that some of their anger in that audience, when people leave the studio, I think they’d be ready to go off and start a stampede because they have been so riled up with so much anger. And I think Bob’s audience go home and they’re kind of smiling and thinking and reflecting on almost philosophizing. And in a way, I would put it this way, it’s almost as good as a good sermon.

Interviewer: Let’s stop for a second. First off, I want to ask you, you know. Can you tell tell me when he moved to California. What was happening at that time?

Jack Spatafora: Bob moved to California in, I think, in the 60s when he began doing television. You have to I think he wanted to live in Chicago if he could. But you couldn’t. And and he went out there and and I think he really grew to like it. And he’s like so many people in show business. He loves golf. And he can play golf in Chicago but can’t play golf in Chicago. Twelve months a year. Out there he can.

Interviewer: So what do you remember about the 1961 variety show?

Jack Spatafora: That was the first chance that all of us here, back at home got a chance to see Bob on a regular basis, on a network outlet and so on. And it was a great show, a funny show. But I got to tell you, even though I’d won the Peabody Award, it was not I felt his element here that they were trying to make him into. At the time, there was a Perry Como show, I guess, and then there was the Dean Martin show. And he was supposed to be, you know, the guest. I mean, the host. And he would take the guests out and he would do little routines with them and he maybe would sing with them and then the dances. This was not Bob. And so as a result, I think he felt a little uncomfortable because it wasn’t what it brought into it to what show business. And so, as it turned out, the show was a very classy show, but the public must have instinctively felt the same thing I felt, and therefore it got canceled the same time it got an award. But I’ll tell you this, and this is a story that was interesting, Bob said at the time. He said, well, it was an interesting experience. I learned a lot. I learned some things to do, certain things not to do. But the one thing I learned is that television is a well-paying industry. And he said, I made enough money on this series just in this one year that I’ll never have to work a day in my life. And I said to myself, wow, that really is big paying. And Bob is a frugal man. So I would suspect he probably took that money. And to this day, he’s probably still got some of that money and investments and probably doesn’t have to work a day in his life. Of course, obviously, since then, he has multiplied his fortune many, many times over again.

Interviewer: What did you think was his element then? When did you see him hit like that’s where he’s meant to be?

Jack Spatafora: Obviously, my opinion is what the country’s opinion is when they decided to make him a psychologist in Chicago. And even though people have had fun showing how the way he enters the beginning of the program to his office in Chicago, getting off the island. So all that’s wrong, the geography of that’s wrong. But, of course, who cares? Once it gets to that office and he begins to do his his thing as a psychologist, it just becomes extraordinarily funny. Bob, I think, is one of those comics who is always admired on Johnny Carson was another one. They admired Jack Benny. Jack Benny’s premise was, I would be the butt of the jokes. I surround myself with funny people. Jack Benny always did that. Well, Bob did the same thing. And the people in Bob’s case, he was straight. Bob Newhart kind of a person. You don’t I mean, Lokey, no nonsense doctor or psychologist. And he had the weird things in his story. It was, of course, all these crazy patients. And so that’s that’s the way it worked. They had a galaxy of bizarre personalities surrounding this very low key doctor who was trying to help people and hence the humor from the series. And it was it had longevity because, again, it was just like his his comedy routines. They were dealing with the pains and the pains of human emotion, pride and paranoia. This that the other thing. So everybody who will watch the show could identify with the patients and they could also identify with the way in which Bob, in his own funny way, try to help the patients. And that’s probably that’s the key to his longevity. Everybody remembers a Newhart in that particular series only had two follow ups which were almost as successful. But that one, of course, was the I think the pinnacle.

Interviewer: How would that character is that the Bob, you know.

Jack Spatafora: Yes. The character in the Bob Newhart Show is Bob Newhart. That’s The Bob Newhart. I know he doesn’t have to act. He is projecting himself, which I guess is the greatest acting of all in a way. Not everybody can do that. But I’ll tell you, Bob, when you see him, if you know Bob and when you see him on a show like that, you know, you say, gee, that’s that’s the guy I know. But he is also the same guy when you see him coming by and visiting his hometown. And he’s done that on various occasions and will meet and talk and his friends will say the same thing. And you say, gee, Bob hasn’t changed. And that’s one of the things that I think most old friends have real trouble with when a friend becomes a star. They say it’s gone to his head. It’s not the same. It’s just all unfortunately different. Not with Bob. I’ve never sense that. Never felt that. And I’ve got to say that not it doesn’t get back to Chicago all that much, but I will frequently write to him. Unfortunately, my letters frequently are telling him about certain peers that have died. And he always says, please, no more letters. Every time you send me a letter. It’s bad news, but I stay in touch with him on a variety of ways. And he always responds Christmas cards and birthday cards and notes and so on. Now, he doesn’t have to do that, but he does. My daughter had a radio show in Chicago for a while and I called up Bob and I said, would you possibly consider doing an interview with her on the on the air? These are short. And that was a thrill. Machines blew her away and but he didn’t have to do it, but he did it. And it was it was a lovely thing. And so he does things like that. And so he doesn’t change. He’s a constant.

Interviewer: Were you the one whot to say that gossip columnist here who wrote about him in.

Jack Spatafora: Oh, that’s that’s a yeah. There were some there were some columnist in Chicago who I don’t remember, I think was a woman, and she began picking up certain stories. And I don’t quite remember what the stories were. But I guess it’s like any career. If you have a good publicist or a good agent, you get stuff in the paper and so on. And there were things that were mentioned about Bob and his prominence began. His visibility began to grow. And I got to tell you this, they had a roast in Chicago, I think I mentioned several years ago. And in that roast, I did a little thing that was meant to be funny. And I guess it is maybe funny. He’d laugh, but it was all wrong. I’ll tell you what it was I was kidding around about. I said, well, Bob, I said there are four stages in every great performer’s life. There’s the stage which should in which they say, Who’s Bob Newhart? The second stage is get me Bob Newhart. Third stages, get me a Bob Newhart type. And the fourth stage is who’s Bob Newhart? Now, in his case, the fourth stage has never come. Everybody still knows and remembers Bob Newhart. He has not faded out at all. And that’s that’s the wonderful thing about his career.

Interviewer: That’s great. Thank you so much.