Speaker Tell me about the Boston theater scene in 1889. Eliza, was she how was she regarded?

Speaker Oh, Eliza, yes, very well regarded. Very well regarded. And she was known, I think, mostly for her versatility, her ability to perform a variety of roles, really at a moment’s notice. I mean, the the theater world and at that time was very harum scarum. And a repertory company was supposed to be able to do a large number of plays kind of on demand, you know, one one night in a different one the next night and so on. And so I think her great value was, you know, her ability to do whatever was was asked of her in terms of performance. She also, of course, had a beautiful singing voice. You know, she was called the Nightingale, you know, and reviewers always remarked on, you know, her musical ability. I’ve I’ve sometimes wondered if the nightingale, you know, had any resonance with PO when he later came to write The Raven. But but that may just be speculation.

Speaker And what what what can you imagine of the two and a half year old when his mother was in the room?

Speaker Yes. Some accounts have him at her deathbed. And if you know that were true, of course, that would be quite a, you know, a shocking thing for a two year old. But even if he wasn’t actually at her deathbed, I’m sure that, you know, her passing had a tremendous emotional impact on him. He wrote about it, I think, in different forms, you know, in throughout his writing career, just about everything that he wrote in some ways, you know, has this young sort of maidenly woman with the alabaster skin and the beautiful singing voice and the fair features and so on, you know, hovering in the background of the story or the poem. So it must have had a big emotional impact for it to stay with him really for his entire life.

Speaker And then he’s taken in by the Italians, just a brief description of who they were and why did they take will?

Speaker They took him in as a charity case starting in St. John. That’s right. Yes. Well, John and Frances Allen took Poe in as a charity case, and I think Frances Allen probably was more disposed to take him in than John Allen was. It was probably the fashionable thing to do at the time. All of the society, women in Richmond, you know, were prone to acts of generosity like this. And I think their husbands probably just went along with them. So it was really Mrs. Allen rather than John Allen that that took Poe in. And that, of course, you know, caused some friction, as you know, in the family for quite some time.

Speaker And what were he who was John Allen? What was he like?

Speaker He was a merchant. John Allen was a merchant, and he was a Scot. So he had that kind of bootstraps character about him, very no-nonsense, very business oriented, very rugged and very individualistic. And, you know, that obviously created some friction between him and Poe because Poe wasn’t like that at all. And, you know, Poe must have really felt out of place in a family that’s promoted that kind of ethos.

Speaker Could you talk a little bit about I mean, my sense was that the young know, the six, seven, eight, nine year old was charming and John Allen and Frances Allen were charmed by him. It was later that, yes, they started to clash. Maybe you can talk about how at first John Allen seemed to.

Speaker Well, there’s actually not a lot of material about that so far as I know. I think that, you know, that’s may well be true, but there’s not a lot of documentary evidence to that effect, the documentary evidence that exists. And again, it’s, of course, selective. Some things, you know, are extant and others aren’t. But most of the documentary evidence that we have about the relationship between Poe and John Allen begins in adolescence and in the teenage years. And then later, when he goes off to to college and into West Point. And that, of course, you know, is a record of real conflict.

Speaker Yeah.

Speaker Could we flash back a little bit to the years that the allies spent in England with that? Mm hmm. Are we picking that up? Yeah.

Speaker Or somebody coming that something outside the Church of England?

Speaker That’s right.

Speaker So I guess what I’m wondering is, can you talk a little bit about how that experience in England and how it affected inform the young and in ways that would show up? If you could start by saying that about 18, 13, John Allen who just wait. Mm hmm.

Speaker Well, in about 1813, John Allen moved his family to England for a business venture. And I think by all accounts, he was initially successful, but then had ran into some financial reversals and had to bring the family home. Well, while Poe was there, he was a student in a private school, and it was a school just outside of London called, I believe, Stoke Newington, which he later used as the setting for one of his most famous stories, William Wilson, The Story of the Double. And he used the school and even the school master, a fellow named Reverend Dr Bransby. Though the contemporary accounts of Dr Bransby are that he was a sort of genial, easygoing fellow in the story, he becomes this stern schoolmaster with draconian, you know, rules for a conduct and so forth. I don’t know if that’s, you know, a later reflection, Beppo, on what he thought of his English school days or not. I do know that there was some animosity between PO as an American and his English classmates because, of course, the War of 1812 had just taken place. And so naturally, you know, there was some had to be some French friction in the air about that. It’s interesting that in his later career, you know, Poe acted very English. Of course, when he became a reviewer and a literary critic, he consciously adopted the style of the English book reviewers. He wouldn’t, of course, necessarily have known much about him when he was a schoolboy there. But when he went into magazine publishing and editing and so on, he made a study of these London Quarterly’s and and they’re kind of slashing, reviewing style and so on. And he he modeled himself after that type of English man of letters, kind of ironic in a way, because he never went back to England. He wasn’t a world traveler. He really didn’t go anywhere except up and down the eastern seaboard. And also kind of ironic because the settings of his stories are English, but they have the sort of quasi medieval setting to them. It’s not England of the, you know, 19th century by any means. It’s England of the Middle Ages or some imagined Gothic, you know, landscape that never existed in England. But that was his idea, I think, of of England as a as a literary place, if that makes sense.

Speaker Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Speaker And John said, well, you referred to this before, but without acknowledgement that you already talk a little the growing animosity between John Edgar and maybe I don’t know if it makes sense to you to put it in the context of Jacksonian America.

Speaker The speaker, perhaps rising class of mercantilism, is trying to identify himself with a different. Hmm. Person.

Speaker I think it does. I think, you know, John Allen identified himself with that rising class of mercantilism there was associated with, you know, Jacksonian democracy and independence and so on. And PO to go back to the English, you know, thing, saw himself as kind of a a man of letters, you know, someone who was learned and cultured and bookish and, you know, a bit of a dreamer. And maybe even in his fantasy days of dilatant, you know, someone who could spend, you know, his time poring over, you know, books to review and writing poetry and, you know, dreaming up, dreaming up stories for publication and so on. And that wasn’t like John Allen at all. So now they’re always two sides to every story. And it is entirely possible that when Poe went away to the University of Virginia, he, you know, as any college freshman would got carried away and neglected his studies and ran up, ran up debts and, you know, overspent his budget and so on. Given pose, emotionally charged character. He could act very impetuously. He was very. Wild in the sense of just kind of doing whatever he wanted. Sometimes I can see him carrying on and not, you know, carrying a whit about John Allen or how much money he had given him or what he was supposed to be doing there and so on. That would be very typical of Beau. So that’s one side of the story. The other side of the story is that people have said that Allen didn’t give him enough money, you know, that he sent him off unprepared, financially and probably other ways to, you know, without any kind of support network, you know, back home or there. And so that PO, you know, had to, you know, eke out an existence at the University of Virginia. I, I suspect that Allen probably gave him a sufficient amount of money. But but that poll was not good with money. And this was the first time he’d been away from home. And also it was, you know, rather the high life at the University of Virginia at that time. All of those students were very well-heeled. They came from these privileged, you know, Virginia families. They all had servants and and Allen being the penny pincher that he was, you know, I doubt that he he gave him those kinds of funds when he way to college, when he went away to college. So.

Speaker One quick question. We are shooting twenty four, yeah, um, yeah, well those days that Yuva that’s when you at University of Virginia, which you probably shouldn’t use.

Speaker Yes. That’s when you first hear accounts of private drinking. Yes. Yes. Talk about that. Yeah. Certainly there was gambling.

Speaker The drive through here that will drive us right.

Speaker And certainly there was gambling at the University of Virginia. Card playing was a. That’s all right.

Speaker So.

Speaker OK, certainly there was gambling at the University of Virginia card playing was, you know, a great pastime and no card playing is any fun, you know, unless there’s some money riding on it. And I suspect that that’s how people got into financial troubles. The drinking also, I think was, you know, part of the university scene. And the University of Virginia was first of all, it was relatively new at the time. It had just been founded a few years earlier by Jefferson. And it was unlike, you know, some of those more strict, more doctrinaire universities like Princeton or Harvard or whatever, at a very liberal atmosphere about it. And, you know, that may have suited DPO just fine, you know, given his tendency to wildness. So not only was there a lot of drinking and partying, as we say nowadays and so on, but I think it was relatively unchecked by the by the faculty or the administrators. So it was easy to get carried away. And I think that’s probably what happened.

Speaker Hmm. I’m going back in time a little to Jane’s standard. We skipped over that. Yeah. Do you talk about her as this?

Speaker Mm hmm. He called his first ideal. Mm hmm. I don’t know if it makes sense, but in the context of his views and aspirations, he’s got love and death. Mm. Gravestones, terrorism and Baturin all swirling around. Mm hmm.

Speaker Remind me now, Jane standards. The Fannie Alan died first, didn’t she?

Speaker No. OK, you know, died while I was in the army.

Speaker Oh that’s right. You’re right. Of course.

Speaker Yeah. He was I think 16. She was the mother. Hmm. And he was. So he was still in Richmond. Mm. Form this attachment.

Speaker Well not much is known about Jane Standard except through Poe’s perspective, you know, through his poems and comments about her in letters and so on. But I suspect that that was mostly by way of a schoolboy crush. And I’m almost certain that she must have reminded him of his own biological mother in certain ways. She had that that same sort of ethereal look about her for want of a better word, word sort of otherworldly. That’s a that’s a bad word for it. Otherworldly in a good sense. I don’t know how to describe that. She was. Pure looking, pure looking, and, of course, his mother, having died when she was so young in his imagination, his mother must have remained pure. She was always this pure maiden, conveniently forgetting, you know, all of her troubles and travails and her failed marriage and, you know, whatever else might have happened to her on that theater circuit, you know, that she lived on for all of her young life. Maybe Jane Standard was a kind of ideal replacement for Fanny Allan in Poe’s imagination.

Speaker Sorry for Fanny Allan out of her life.

Speaker Oh, I’m sorry for Eliza Poe to say. Yeah, maybe Jane’s standard was a an ideal replacement in Poe’s mind for Eliza Poe kind of artificial sense.

Speaker Yeah, the labyrinthian. Can you talk a little bit? It was. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Speaker Well, George Gordon, Lord Byron was an English poet, but of course very popular in America at the time, mainly because he cultivated this image of the isolated artist at odds with the rest of the world. You know, the the Aluf the distance artist living only for his art and having no care about mainstream matters, such as the sorts of things that John Allen, you know, was interested in. And so Poe consciously cultivated that Byronic pose even to the point of dressing in black and, you know, having this kind of abstracted intellectual er about him and, you know, looking in the distance, nothing in particular and so on. I can see him as a as a young man really trying to define himself in some terms because he really had no identity. You know, he was a foundling, an orphan, whatever. He was thrust into a family that, you know, more or less didn’t want him, or at least only part of the family wanted him. He was a Bostonian living in Virginia, really born in Boston, you know, growing up in Richmond. And, you know, I think that he was, you know, as they say, looking to find who he really was.

Speaker And, you know, what a great image to to cultivate if you had these artistic inclinations.

Speaker And, you know, Byron was kind of a pop culture hero in America at the time. What would be the equivalent of that today? I’m not up on pop culture enough to know.

Speaker I think Kurt Cobain is the name, is it?

Speaker I don’t even know who that is, but, you know, someone like Johnny Depp or Leo DiCaprio or someone like that, you know, some sort of dark eyed, you know, matinee idol, whatever.

Speaker That’s good. The James. Mm hmm. I was 16, I think. Let’s see if you can describe what he did. Mm hmm. And what a few did was that speculated about why. What was he trying to promote? Who and why? Mm hmm.

Speaker I remember we talked about that in Charleston. You were very, you know, interested in that. I never attached that much significance to it. But, you know, I know we talked about this. And I do think that he was well, he was athletically gifted. People don’t associate that with Poe, but he was very fit and very athletic, very muscular, but small of stature. And I think, you know, being rather on the short side, that may have been a way for him to to show that he was, you know, as athletic as any of the big, you know, brawny guys that, you know, that played the competitive sports and so on. I think it’s fair to say that Poe often had a chip on his shoulder. And so this was one way that he was able to prove that he was, you know, the equal of any of his peers. It was quite a feat to I mean, you know, that was that was a, you know, an athletic skill that I doubt many of Poe’s peers could have accomplished. Can you say explain what it was, the swimming, I believe, six miles in the James River? Was it against the tide and, you know, against a strong current like that, you would have had to have been very strong to do that and not just collapse afterwards, which by all accounts, he didn’t you know, he was very is very proud of that achievement.

Speaker Oh, I’m just sorry to just explain it one more time. At the age of 16, OK, I decided to swim six miles up the James River in Richmond against the tide just for that.

Speaker NARRATOR Well, at the age of 16, Poe decided to swim upstream in the James River against the tide. And this was a no small feat at all for the time. And I think that he was doing so in order to, you know, show off his athletic ability.

Speaker All right, thank you. Um. We talked about you things that was good, um.

Speaker Culture, the culture of death, the culture of mourning in Victorian America, in 19th century America, there was a very elaborate cult of death that is a fascination with all things involving death and dying, funerals, bereavement, customs, mourning rituals. I mean, people, you know, wore locks of hair, you know, from the deceased’s the loved one’s head in a locket, you know, around their neck. The windows were draped with black crepe paper or draperies. The stationery that the lady of the house used was edged in black. I mean, there were very, you know, elaborate rules for, you know, for how you behaved after the passing of a loved one, you know, but more so than that, of course, the mortality rate was very high. Funeral up excuse me, cemeteries were just becoming customary to have cemeteries, to have funerals at cemeteries, to have long funeral processions and things like that. And and so, you know, while it sometimes seems odd to 21st century readers that Poe was always writing about death and dying, it’s not at all unusual. You know, if you think about what he was witnessing in the 1920s and 30s when he was surrounded by this this cult of death and a premature burial thing that happened. And what I would read about it in magazine, premature burials, accidental burials, whatever you want to call them, actually did happen. And the magazines were full of stories, supposedly. I’m sure some of them were fabricated, but others were probably true of people who had been buried, you know, while still alive. The reason was that medicine and medical diagnosis at the time was more of a, you know, an art than a science was really nothing scientific about medicine at that time. And so it was entirely possible that a person could develop a serious illness and perhaps lapse into a coma and look like they were dead or seem to be dead, but actually were not. And a funny thing is that, you know, given the the mercantile character of of Americans at the time, many fast thinking businessmen came up with ideas about how to sell things that would protect you from premature burial. I remember seeing one ad in a 19th century magazine for some sort of contraption involving a bell that was attached to the outside of the coffin, but was run on a wire through to the big toe of the person laying in the coffin so that if they were buried and awoke, they could wiggle their foot and the bell would ring outside and someone presumably would hear this and they would dig them up and, you know, they wouldn’t wouldn’t be killed. Sounds sort of Rube Goldberg to us today. But I think probably, you know, there were a lot of sales of those sorts of things. And so they were all in the magazines, which Poe was devouring omnivorous at this time. So he was getting a lot of good material that way.

Speaker Let’s skip over the soldier part.

Speaker Yeah, no, not really. OK, again, not much is known. Yeah, yeah, yeah. I mean, publishes his first book of poetry.

Speaker Anything you want to say about him?

Speaker Not really. No. I think that a lot of that is forgettable. Others will disagree with me.

Speaker But I think that I would like to get back. And one of the things in your book really well, let’s talk about when he lands in Baltimore after getting kicked out of W.

Speaker Mm hmm. And he finally got this. You just described what that was like. Oh, why are you going to go for who was the cast of characters? Hmm. Yeah.

Speaker After he left West Point, Poe went to Baltimore in search of family. The only true family, biological family that he had was in Baltimore. So it’s entirely natural that that’s where he landed. And throughout his life, Poe was sort of desperately in search of a family. It. Is in Baltimore, really, that he began to cobble together a sort of family made up of Mariah Clem, who is his aunt Virginia Clem, who was his first cousin, Mariah’s daughter, and also oppose brother William Henry Leonard Poe lived in Baltimore. And, you know, they kind of formed this sort of loose confederation that gave Poe the emotional sustenance that he needed in order to, you know, as he felt, you know, fight the fight against the travails of a very cold and impersonal and unloving world. There is so much emotion in those stories that Poe wrote. It’s it’s a kind of passion that we sometimes misread for for horror or for shock. But really what it is as a base emotion is its passion. It’s a kind of love. And throughout his life, you know, he was searching for an equivocal love. And that’s why he kind of, for want of a better word, glommed on to his aunt, whom he didn’t know, you know, and that’s why, of course, eventually he loved Virginia so much that he felt compelled to marry her, to kind of keep her in the fold, you know, to keep her close to him. And and I think he feared, you know, not I think he feared losing her as he had lost the lives of his mother and Jane standard and so on.

Speaker And so he’s there struggling to be at one point twenty.

Speaker And, you know, no matter what.

Speaker Yeah. Yeah. And talk about his absolute burden. Yes. Yes. Absolute kind. And then if you could lead us to the fact that he finally wins this prize. Yes.

Speaker Well, first of all, Poe’s great ambition in life was not to be a writer, but to be a poet. Poetry is my passion, you know, he said in different forms over and over again throughout his career, he always thought of himself as a poet. An irony since, of course, today he’s best known as a story writer or more specifically, a horror story writer. He never thought of himself that way, but he always thought of we thought of literature as a very high calling, you know, a noble ambition within that poetry was the the highest or the most noble of all of those literary ambitions. And that’s why the earliest efforts that he made, so to speak, as a writer, were towards poetry rather than prose or or fiction. Poe was also someone who was determined to be a writer. I’m not entirely sure now that I think about it where this, you know, seed got planted or, you know, where the idea really began to take hold in him. But by the time that he landed in Baltimore and began writing seriously, that is with a view to getting published. You know, his ambitions to be a writer had been galvanized and really, you know, nothing would get in his way at that point. The the slide, so to speak, from poetry into fiction, was born, as most things are, of necessity. He needed to earn a living. He needed to get his name out there. And Prince, he needed to, you know, get people to notice him and so on. And so he ended up writing this story. Now, very famous manuscript, found that a bottle, which he entered in a contest for a Baltimore newspaper with a Baltimore newspaper and ended up winning it and won some modest prize money. And, you know, that kind of set him on his way, I think, to writing more stories.

Speaker Do you remember that sad moment when Kennedy, one of the judges, invited them to dinner to celebrate?

Speaker Yes. Doesn’t have any clothes, you know. Yeah, just telling that.

Speaker Well, one of the judges of the newspaper contest that Poe one was a man named John Pendleton Kennedy, who is barely known at all today except as sort of a footnote, you know, in literary history. But at the time, he was a very well-known writer, a writer of sort of pastoral romances and things like that. And as a literary figure in Baltimore, he was kind of a kingmaker in some ways. I suppose making connection with him was, of course, a very good thing and. He took tried to take power under his wing, he he was a mentor figure for PO. And then there’s a famous moment in Poe’s early hungry years as a writer where John Kennedy invites him to dinner at his house and Po writes back begging off because he says, I don’t have a suitable suit of clothes to wear. And that sort of typifies, you know, the the straights that Bo was in at the time. Great talents, you know, a huge genius, great potential. But, you know, just not quite not quite there yet.

Speaker You know, the accelerator.

Speaker So this is great. How are you doing?

Speaker Yeah, it’s kind of artificial as well. Don’t. OK, good, good. I, I feel like I’m thinking about what I’m saying, but I guess I don’t know.

Speaker It’s better that way. I think it works better when we say it does. It does. It’s you know, on camera. OK.

Speaker All right. It feels very natural. Right.

Speaker These days, you know. So out of the blue, I know I get a phone call from some eighth grade class and I don’t even remember where it was.

Speaker You know, we’re doing a project on Polke and we ask you some questions that the attention span of, like a smart eighth grader, their brains are not really engaged.

Speaker Well, I’m sure you all will edit it to the, you know.

Speaker Yeah, it feels good to me. All right. So in this period of Baltimore, John dies.

Speaker Yes. Yeah. What was the impact of that?

Speaker Well, of course, the impact of Poe not receiving any of John Allen’s, you know, huge estate, his wealth was tremendous. Now, I’ve often wondered why Poe thought he would get anything from John Allen, given the long history of animosity between them. I think that that says something about Poe’s character. It was typical of him to say, how shall I say it? You know, to have expectations of people that were at odds with those people’s perceptions of him. It was the same thing when he wrote to famous writers later in his career asking for them to contribute to his various magazines, Washington, Irving Cooper and so on. He thought it would be the most natural thing in the world for Washington Irving to get a letter out of the blue from an unknown hack or editor named Edgar Poe asking for, you know, an article for the magazine and that Irving would just, you know, write something up and, you know, send it in. As a matter of course, it was that same, you know, type of attitude, I think, that applied to his shock, his being shocked when John Allen didn’t leave anything to him. And as well, it’s interesting because as you may know, John Allen had several illegitimate children, as well as legitimate children, and even the illegitimate children were recognized in the will.

Speaker But Poe got not a penny. That’s tough.

Speaker Do you think it made him feel in terms of a breaking point in his life, that was the breaking point between PO and his life in Richmond and his memories of being part of the Allen family? It’s been noted that although we think of him today as Edgar Allan Poe in his lifetime, Poe never used the middle name, the Allen name in any of his writings. He never signed his name Edgar Allan Poe, perhaps once or twice. But it was always Edgar Poe or Edgar Allan Poe sometimes. And, you know, I think that gives great insight into how he felt about, you know, his early life with the Allen family.

Speaker Yeah.

Speaker So is the other literary messenger, his first real job? Here he is, he’s the real editor.

Speaker Mm hmm. And he also publishes this story. Marentes Oh, Isiah Thomas. Ed, with you, remember? What’s that?

Speaker They have an argument. Yes, they have an argument where the Thomas White says this is grotesque.

Speaker Yes. Yes. I want to publish this. Yes. And terrible taste.

Speaker And Poe’s response to Thomas White about Thomas White’s objections to publishing something is sensationalistic and vulgar and grotesque is Bernice is very telling, if you want to refresh. Well, I think I can remember it more or less from memory. He says that, you know, in order to be read. Wait a second. What is it? In order to maybe I should I don’t have my glasses so you can read. Poe had an almost mercenary attitude toward writing for the magazines, though.

Speaker OK, I’m sorry. Are you going to start over again?

Speaker Poe had an almost mercenary attitude towards writing for the magazines, and he felt quite correctly, you know, that in order to be successful, you had to be read so you could be writing whatever you wanted. But if it wasn’t, you know, finding an audience, if it wasn’t something that readers were interested in reading, it mattered, you know, not a whit. And so he was struck by the effectiveness of these gothic, sensationalistic stories that had been published in the London Literary Quarterly’s. And he really, you know, was the person that imported those into America, made them popular, made them a staple of magazine reading. And that was his formula for success. That was his path to to success. And of course, it was very effective. The magazine was on the rise in America at the time and people needed something that they could read in short bites, so to speak. And so the short story was perfectly suited to that. And a short story that, as Poe later described it, revolved around a single effect that built up to a an emotional climax that the reader, you know, really felt empathy with the character at that point or felt that they were in the story at that point. That’s how he he structured, you know, his stories. Could you talk a little about Barondess so that that debate why his editor at the Southern Literary Messenger, Thomas White, was a person of sort of Presbyterian rectitude and the like. You know, John Allen, this was someone that Poe didn’t naturally. Well, they got along, but they were certainly of not of the same mindset about writing and about literature and so on. And Thomas White felt that Barrenness was was vulgar, was much too sensationalistic and and coarse for for the audience, for the magazine. But Poe defended it by by saying that in order to to be successful, you must be read. And that was his path to finding an audience.

Speaker Thank you so much during this period that he’s developing his identity as a as somebody who wants to elevate American literature and do that through criticism, through good writing.

Speaker Mm hmm. Talk a little about that mission. What was his mission? What did he see?

Speaker First post saw himself as the upholder of high standards for literature. And he was writing at a time when there wasn’t a lot of American writing to begin with. American writers were were always living in the shadow of the great British writers. Even the successful American writers were sometimes thought of as American versions of, you know, Dickens or Scott or Thackeray or someone like that. So there was, you know, a bit of a literary inferiority complex among Americans at the time. And Poe, rather than take the easy way, I think, which would have been to they called it puffing, you know, that is just sort of mindlessly praise anything that had been written by an American, as he later said, simply because it is by an American. You know, he took the more he took the more challenging route, but also the one that had the greater long term value. And that was he said, we must uphold we must have high standards for for writing and we have to uphold these standards and we have to be reckoned by the world, put on the world stage as great writers, not as great American writers, but as writers that could hold our own with the literary greats of the Western world. And I think that that is the reason for his for the harshness of a lot of his literary reviewing, a literary literary criticism. He certainly pulled no punches. I think, you know, to be honest, a practical benefit of that was that had got him noticed, you know, kicking up the dust, he called it, you know, so drawing attention to himself. But I think also, you know, is was high minded. And he really did feel that, you know, someone had to be the umpire. Someone had to be the arbiter of literary taste in America. And so he took that mantle and, you know, put it on his own shoulders and and was quite successful at it. He was a trenchant literary critic. He was also writing a kind of literary criticism that didn’t exist in America at the time. Most book reviews, quote unquote, were really not reviews of the book in the sense that they were not assessments of the strengths and weaknesses of the book under review. They were a kind of discursive, wide ranging essays about the subject of the book. In other words, the book’s topic was just a platform for the literary reviewer to sort of take off and, you know, write about his own thoughts on the subject opposed. Poe’s book reviews were not like that. They were really the forerunner of what we later came to know as formalised criticism or new criticism, where the text itself is the object of analysis. And Poe would do a line by line, word by word dissection of the text, such as a professor would do in a, you know, a freshman English classroom. And he would really, you know, go through it and he would hammer the writer if the writer, you know, did not use the language well or was concocting improbable plots and contrivances and so on. He as I say, he pulled no punches. This got him noticed. But of course, it made him a lot of enemies, too. And that would would come back to haunt him later in his career.

Speaker Thank you. So he marries this 13 year old first.

Speaker So what can you say?

Speaker So tell if you could just and then expository way say well, and while in Richmond lovingly calls for money, Virginia to come marries house. And that was that scene then.

Speaker Well, I was alone in Richmond. He’s working at the Southern Literary Messenger. He’s left his, you know, family surrogate family, only family he has behind in Baltimore. He’s working hard. He’s terribly lonely. You know, he’s at a tender and vulnerable. Age two and his young 20 early 20s, and he’s left behind people that he loves and we’ve all experienced that, you know, when we’ve been part of a place and part of a group, and then we’ve gone off on our own somewhere. And I think that’s perfectly normal to have those pangs of longing. So the first thing that he does is he writes back to his family, his aunt Maria and his cousin Virginia. And specifically, he he attaches this longing to Virginia because she is a Carmeli young girl, very pretty as yet, unformed intellectually. You know, he sees her, I think, in part as his almost as a student, you know, someone that he can take under his wing and shape in a certain way to be aesthetically alive to the world and nourished intellectually, you know, by books and discussion and things like that. But of course, he’s also very much you know, he’s he’s a man, a young man. He’s in love with her. And he you know, he needs that emotional connection. Also had a cousin in Baltimore, Nelson Nelson Poe, that had maybe not started courting Virginia in Poe’s absence, but he was kind of making his move, I guess. You know, he saw it opening and Poe was terrified that Nelson would swoop in and take Virginia away from him. So he began writing these really desperate letters in which he convinced Mireia and Virginia to come to Richmond to live with him there as a family. He eventually married Virginia and and set up, you know, a family there in Richmond.

Speaker How do you think people look at it? He was 27.

Speaker Yes. She was not quite 14.

Speaker And if you could just say that the ages and talk about how you think it.

Speaker Well, Poe was twenty seven and Virginia was not quite fourteen. And in order to to be married, they had to lie about her age. So it was obviously, you know, something that was disapproved of at the time. Poe’s employer at the Southern Literary Messenger, Thomas White, greatly disapproved of it. He was a witness to their marriage, which must have caused him a lot of consternation, given the sort of morally upright person that he was. But they fudged Virginia’s age on the marriage certificate and that was that. I think, you know, Poe would do whatever was necessary to not, again, lose someone that he was so close to.

Speaker Thank you for doing.

Speaker It’s been about an hour or so, you know, OK, well, I’m OK. You said an hour, so I know. Yeah, yeah, I wondered about that.

Speaker But we can, you know, do do more, you know, moves to New York Publishers P.M., 6:00 p.m.. Do you want to talk about that or do you want to move.

Speaker Oh, let someone else talk about it. I mean it’s a fascinating book, but yeah.

Speaker So so after New York. Philadelphia, let’s just go to that. He’s working for Burns magazine. Right. Really become a professional magazine. Yes. Really pretty much in the thick of it. And he’s also beginning to publish. Yes.

Speaker I’m sure that was a great period. Yeah.

Speaker Yeah, we talked about that. So he lands on his feet. Really?

Speaker And what is productive is he how hard is he going to give a picture of the family to what what’s that period like the years that Poe lived in Philadelphia, where in some respects the greatest years of his life, both personally and professionally, he was firing on all cylinders creatively and also editorially, that is working as a critic, book reviewer and what in the 19th century they called a magazine that is a kind of professional editor and writer of magazine material, professionally earned his living really as a as a journalist, that is, his income came from shepherding these issues of Graham’s magazine, first Burton’s gentlemen’s magazine and then Graham’s magazine through the production process, marketing the magazine to to the audience, bringing in subscribers and, you know, generally doing the sorts of things that made the magazines financially successful. He earned his living really as a day to Day magazine editor. As such, now in his creative life, Poe would go home from the office, so to speak, you know, every evening, have dinner. And then he would he would write in the evenings and he would stay up, you know, late into the night writing. And sometimes Mariah Klemm would sit beside him, keeping him company while he composed these stories that were totally unlike what he did during the day. He was a very conventional, prosaic middle class wage earner during the day. And then at night he went home and his creative imagination fired itself up. And he began to imagine these, you know, bizarre, sometimes grotesque scenarios. And he would he would write them all up and stories, sometimes reading them aloud to to to Muddy, as he called her, Moriah Clown, as he wrote.

Speaker So he was incredibly productive and industrious. And then also, what was he putting his finger on? The pulse of something that Americans seem to want. Hmm.

Speaker Oh, that that’s a good question. I’m not sure that I can answer that. He was he obviously was successful. He had his finger on the pulse of readers imaginations. It was not something specifically American. I don’t think it was not something that was tied to the the social trends or the cultural contexts of the time. It was something I think really more primal than any of those things. And it was the possibility that even though you lived a prosaic conventional life, something really, really weird and of course, totally unexpected could happen to you. And that was Poe’s great talent, was his ability to put the reader into the story. And it was a fantastic talent, primarily because the story, the scenarios were so bizarre. Who could ever imagine, you know, that they would be, you know, strapped to a giant disk, you know, in a hole, a pit in the floor and have this giant, Sithe, you know, swinging back and forth and moving downward toward you? I mean, that certainly is the stuff of nightmares. And that was the the prime. Will fear that Poe knew existed in everybody and that was his his path to success as a writer, and he meets someone named Rufus W..

Speaker Can you tell us who. Right. They why did their paths crossed?

Speaker That’s one of the most fascinating stories in American literary history. Rufus Griswold sort of became the Moriarity to pose. Sherlock Holmes is the way that I like to think of it. They began as like minded friends. They Poe would not have said this, but I think that Griswold was as smart and savvy and intelligent as Poe was. Poe didn’t want to admit that. But like Holmes and Moriarity, they were you know, they were on the same wavelength. And for that reason, you know, they could have been partners for good. But instead, you know, relations deteriorated between them, as sadly they did between Poe and just about everyone that he knew professionally. And so they became, you know, instead of partners, they became enemies or antagonists. There was a lot about Rufus Griswold was a a true man of letters as the 19th century term had it. He was a an editor, a critic. His main success came from publishing anthologies of American writers and anthology isare. And in that way, he was a great promoter of American literature and very successful, very well-respected, widely regarded. Now, this was what Poe was trying to do, too, in a sense, with his literary criticism of his book reviews. And so that made them naturally rivals. They began as friends. They ended up as enemies.

Speaker We’ll get to that later, OK, because we have to do now, which also means Charles Dickens.

Speaker Yes, it’s great that at one point I’m going to come out and push back. But also, what time is he coming? He was slated for the new year. OK, yes.

Speaker OK, Charles Dickens, can you describe what that meant?

Speaker Why was that meeting? Charles Dickens was one of the high points of Poe’s literary life. It was a great honor for him because Dickens was certainly the most celebrated novelist in England at the time. And Poe would have liked very much, you know, to have had the stature in America that Dickens had in England. Dickens was a bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic. And so in 1842, I believe he came to America for this very celebrated lecture tour. And Poe had the opportunity as an as a writer for I believe it was Graham’s magazine to interview Dickens and I think got to part profile of him. And then later in in Poe’s literary criticism, some of the theoretical writings that Poe later composed about about fiction owe a lot to what he learned from Dickens about the manipulation of plot, about the sense of an ending, what else can’t remember what else off the top of my head. But but certainly that was a high point of his career.

Speaker Take that computer outside. I hate this stuff. Yeah, yeah, just, um, just this one. Uh, or if we put up way back in that corner over here.

Speaker Yes. I you it takes forever to, uh, just take it outside, OK. Yeah.

Speaker Yeah. It’s just like a stone. Jackson if you can hide it under something just you just stay out there, you know, and I’m going in here OK. Just guard it.

Speaker Well I think about something.

Speaker Um, if I ask a question, when we get rolling the cameras and frigid temperatures for the first time and probably refers to it ever after as a singing, let’s give it a sense of what is he thinking?

Speaker Talk about denial. You could just say you don’t seem to be a really high moment in their lives, apparently.

Speaker Solid job. Yes. You know, meeting Dickins and then this horrible thing happens. And how does co-respondent how do you think it makes you feel? Yeah.

Speaker Well, when they were living in Philadelphia and everything was going so well, in fact the life in Philadelphia was really the the the picture of middle class gentility, you know, domesticity. They had a little house. They had a little yard. You know, I think they had some pets. And I think thinking back to Alysa, memories of his mother who wanted Virginia to to learn music, to sing, to play the piano and so on. And so one afternoon or evening, she is singing and she seems to burst a blood vessel. The blood starts to come out of her and I guess it’s her mouth or her nose. I can’t remember which. And it’s the first signs of tuberculosis. But Poe refuses to believe that it’s anything other than a minor medical matter. He refers to it euphemistically as a as a singing accident, which is surely one of the, you know, the oddest descriptions of something like that happening to someone that I’ve ever heard and for the rest of his life. Well, for the rest of their life together. Until Virginia passes away in 1847, Poe is in denial about the slow, painful, you know, process of a deterioration that his wife is going through due to the tuberculosis. And it’s, you know, it’s like the death of Eliza all over again, like the death of his mother all over again here. Everything was fine. And then suddenly the fates whimsically, you know, decide to strike, strike his happiness down and take it away from him. And, you know, that was very much the pattern of his life. Sadly, it’s no wonder that, you know, he felt that he was always struggling, you know, against the rest of the world because things like that seemed to happen to him with great frequency.

Speaker It’s very nice.

Speaker Uh, what did publishing The Raven do for people? Why was that?

Speaker Such a turning point in publishing the yeah, publishing the Raven was the the greatest success Poe ever had. It was the the one piece of writing that earned him a good bit of money. But more importantly, it earned him a large measure of fame, something about it. It was kind of a one hit wonder. In some ways it was it was the poem that was just musical enough and memorable enough and spooky enough and I think unconventional enough. Also, it was, you know, something different from mainstream poetry that it struck a chord with American audiences and it became memorably and repeatedly reprinted and parodied also, and even became used as an advertisement for such things as as soap and tar water and so on. And so Po Po’s name, you know, became attached to the Raven. And this, you know, brought him great, great celebrity.

Speaker And yet almost immediately afterwards, he was attacking Longfellow.

Speaker Yeah, because we would wait for all the noise and chaos out there. They tell us they were going to be doing all this.

Speaker So there’s there’s like huge there’s like piling stuff into this freight elevator, which is just on the other side.

Speaker Yeah, yeah. I can tell it’s not. Yeah, I have not heard any like we’re going to have a lot of creepy music under.

Speaker There you go. Yeah. So yeah. If you could talk about this moment of his greatest success, in a way he has to shoot himself in the foot yet again.

Speaker What is that. What is is.

Speaker The year 1845 when Poe was in New York was a year of triumph and tragedy and the tragedy was of his own making, which sadly was typical of Poe. It seems that as soon as he would get a foothold in something and would, you know, be on the path to solvency and success and celebrity and so on, then he would shoot himself in the foot and do something, you know, to undo the successes that he had. So he had this great success with The Raven and he was finally, you know, becoming known. And then for some completely bizarre reason, he decides to pick a fight with the most loved poet in America at the time, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, you know, couldn’t have picked another target. I mean, I often think that, you know, Poe reviewed everybody from, you know, the fourth tier to the first tier of writers. So if he is going to accuse someone of plagiarism, which is what he accused Longfellow of, you know, why not pick someone who was, you know, who is a sort of a lesser target? I guess Poe wanted a challenge. You know, if he was going to go, he was going to go big. If he was going to go out, he was going to go out with a bang. So he goes after Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, a veritable American poetic institution all to himself and poet always had this pet peeve about plagiarism or conversely, originality. It was ironic since he himself borrowed, I think, fairly liberally from a lot of other writers. But he launched this what can only be described as a as a campaign and which really became eventually a campaign of character assassination and a series of ad hominem attacks on the person rather than the the product that is the writing itself in which he accused Longfellow of, he called it purloining the central image of a Tennyson poem and using it in his own writing. I think at the Tennyson poem was midnight mass for the old year, which we only know of today because Poe made it famous, you know, by saying it was the source of Longfellow’s plagiarism. Tennyson was one of his favorite poets. And I think that he was influenced by Tenison quite a bit, particularly in terms of the the sound of his poetry, the musicality of what he wrote in verse. But I don’t think that, you know, he was that fond of Tennyson. I don’t think that he was trying to defend Tennyson’s honor. I think that he was trying to give a measure of comeuppance to someone that he regarded as not that great a poet. Long’s worth I mean, excuse me, Longfellow. I mean, who had achieved this undeservedly high reputation. And he thought he should not be so exalted. He’s not that great. I’m as good as he is. Let’s take him down a notch. And of course, it became the beginning of the end for Poe. In some ways it was most things went downhill for him, you know, after the Longfellow skirmish in 1845 and. Yeah.

Speaker Sad story, so 1847, January 1st. Now a cold spell averting a dive in there, freezing Fordham College, how to describe what did that do to what was he like in those moments after his death? What would people describe?

Speaker One thing that can be said about POWs? You know, I think he had a great measure of empathy. I think that he, you know, himself had, you know, struggled through all of these battles and travails and so on that so that when he saw someone suffering, he kind of went through it himself, too. And that would be more pronounced with, you know, his young wife, whom he obviously loved and, you know, wanted more than anything for her to be able to survive this this illness, as he referred to it. But it really wasn’t an illness. It was a it was a, you know, a guaranteed certain painful death. Tuberculosis was at the time. So when Virginia did die, Poe, you know, was struck a heavy blow emotionally and he was reeling from it for four months and months afterwards. It was a long time before he could regain his emotional balance and start trying to write again, though I hasten to add that he really didn’t write that much and that much of great value, I think, after Virginia’s death. And to make matters worse, her death was, you know, as grotesque as almost anything Poe could have imagined in his own story, writing, they were in this cold, drafty cottage in Inforum, New York, and she was laying, I believe, on a straw mattress on the floor. And to keep her warm, he had taken his his great coat. That is the coat that he had when he was in the army. Apparently, it kept with him, kept it with him all these years. And so he covered her up with that, you know, that was the blanket.

Speaker And there was nothing that he could do after a certain point but sit there and watch her die and. You know, that’s a that’s a struggle that we wouldn’t want anyone ever to have to go through.

Speaker Again, I was sort of jumping ahead, but at the last. Oh, yeah, totally. Mm hmm.

Speaker Here’s how you described it so beautifully in your book.

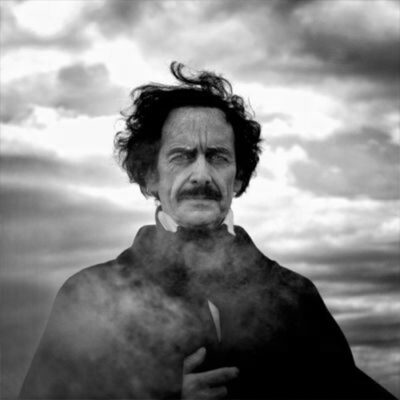

Speaker Well, that it’s the last daguerreotype of Poe called. The ultimately is one of the most haunting images, I think, in in American history. In the photograph, everything about Poe is slightly askew. His mouth is crooked. The mustache, of course, is crooked. His eyes have this sort of blank, vacant look about them. And to me, it’s always been the the picture of intense suffering, unrelieved suffering.

Speaker And I think by that point also of almost being disconnected from the world, the feeling that there wasn’t much else for him here, he could not have predicted.

Speaker Of course, you know, what was going to happen to him in in a very short span of time afterwards. But it’s also possible that, you know, that subconsciously he may have felt that, you know, that things were running out.

Speaker Certainly the image conveys that.

Speaker And just a few days before that, yes, he attempted suicide. Yes, sir.

Speaker It contains Poe was in love with a woman named Sarah Helen Whitman, who lived in Providence, Rhode Island, and they had had a courtship that had culminated, Poe thought, in her accepting his proposal of marriage. Then things are kind of murky after that. But apparently people who knew Poe initiated a kind of whispering campaign against him as often was the case. And word got back to Sarah Whitman that Poe was an alcoholic, that he was not, you know, reliable and would therefore not make a good spouse. When Poe learned that Sarah Whitman had spurned him or decided not to marry him. He the wheels really came off and he tried to commit suicide by taking an overdose of laudanum, which was a very common type of pain reliever at the time. But but did not did not take enough, you know, did not was not successful at killing himself.

Speaker Just for the record, can you add that this is the only known evidence of poetry taken drugs?

Speaker Oh, yes, that’s right. One of the great myths about Poe and think in popular culture is that he was a drug user, a drug abuser, that he was, you know, addicted to all kinds of, you know, opiates and things like that. But there really is no evidence anywhere in the documentary record that that Poe used or abused drugs in any way. The only time that drugs ever pop up in the entire biography is when he took an overdose of laudanum after his being jilted by Sarah Helen Whitman. And of course, he went into a deep depression then and I think seriously tried to commit suicide. But Poe is not a not a drug addict, as we say today, in any sense of the word. If he had been there, surely would have been some mention of it by his contemporaries because his contemporaries were not exactly discrete. You know, all of Poe’s dirty laundry is out there on the record and there’s nothing in it about drugs. So there you have it.

Speaker And then the last one, I mean, there about there are a couple sort of big global ones, but the Ludvig obituary.

Speaker So that is also what happened in just a day or two after Poe’s death, what it was. All right. Why? What effect did it have in the short term and what effect did it and why did it?

Speaker Not sure I can answer the last part of. Shortly after Poe’s death, Rufus Griswold, who whom Poe had in a bright moment of their friendship, he had appointed him as literary executor. Griswold slandered Poe in a an obituary that Griswold wrote for one of the major New York newspapers. It was so excoriated, excoriating that he didn’t even have the courage to sign it. But he used the pseudonymous Bilan byline, Ludvig, who was the mad king of Bavaria. And in this obituary, Griswold’s circulated all sorts of scabrous lies about Poe. Many of them persist to this day. Some of them were that Poe was a drug user, that he was really, for all intents and purposes, a wastrel. You know, that is a good for nothing who never did any work and sponged off others and so on. Some of the lies were truly outrageous. There was one insinuation and part of the obituary actually was not in the obituary. It was in the longer essay that Griswold wrote as an introduction to the posthumous publication of Poe’s Collected Works Works. And the outrageous lie was that Poe, it had an incestuous relationship with his aunt Maria Clinton. Why Griswold turned on Poe, you know, so, so viciously like this after Poe’s death. I’m not sure. The most likely explanation is that, you know, that Griswold saw it as a way to get back at Poe for slights, whether real or imagined that Poe had made against him when they were rival editors and rival writers and so on. And probably also, you know, like Poe saw sensationalism as a key to being read. I’m sure that Griswold, you know, also saw this as a way to, you know, to puff himself, as, you know, a great writer who befriended a madman and, you know, was now writing to sort of set the record straight about this really odd and, you know, potentially criminals. Fellow Poe, I think there was a measure of that poor Mudie, though. I mean, she was devastated by that, not just by that one lie, but by the whole obituary and the whole manner in which Griswold ended up publishing, you know, Poe’s collected works. I think that he probably he got Murray’s permission, Mariah’s Klemm reacclimate permission to do it. And I think he probably promised her that she would earn something from it. But as far as I know, she she never got a cent. And what role did what did Griswold’s off what did he say by publishing that obituary in which all of these scabrous lies about Poe were circulated, Poe established the modern image of Poe.

Speaker Sorry. Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker In publishing that obituary and circulating all of these scabrous lies about Poe, Griswold succeeded in establishing the modern perception of Poe. And that’s the perception of Poe really as the same person as one of the characters in his stories. As someone who is mentally deranged, as someone who is homicidal, as someone who is, you know, a maniac drinking drug, using, you know, womanizing scoundrel. And I hate to say it, but to some degree, I think that popular image of Poe persists even to this day, despite all that’s been written, despite all that’s been said, people love to think of Poe as the same sort of person as the characters in his fiction. Griswold did a lot of damage to his long term reputation. And it really wasn’t until after the Second World War that academics, you know, began to do serious, informed research on Poe and to publish, you know, authenticated scholarship. That set the record straight, but of course, you know, academics, right, to a very small audience. So the popular press, the magazines and the newspapers and of course today blogs and, you know, other media love to present this image of Poe as someone like a character in his own fiction.

Speaker Why does he have to lie to his stories and to her, why does every generation and why do artists break it down when he an.

Speaker Poe is an original. He was he was unique, the scenarios that he imagined were, first of all, unlike anything that had been written at the time, but have their roots in this primal human sense of fear of. No matter how good things are going, no matter how stable our lives may be, I think there’s always in the back of all of our minds, you know, that, you know, milimeter of a lurking doubt that it could all fall apart at some point and tapped into that that that primal fear and all of us. And that’s been a great inspiration for later generations of writers. I’m hard pressed to think of many a writer who has not been influenced by Poe in some way and not just writers, but musicians and filmmakers, of course, and painters and artists of all stripes. Poe, you know, endures today in such a way that I don’t think any other American writer endures.