Speaker We are on speed speed, so described as the best you can post age, he was 40 post condition when he arrived in Baltimore on that his last journey is on its way to New York.

Speaker Yeah, Beau died at the age of 40, destitute and decrepit and drunk. There’s a lot of mystery around the actual circumstances of his death. The cause of his death is a mystery. But much of that mystery is laid upon Poe by his later biographers and romance. There’s something I think Poe would have found delightful since he was nothing if not a romantic, and he delighted took great pleasure in the romance of the darkness of his life. Nevertheless, his life in the 1940s in particular was quite dark. The lives of most Americans in the 1940s were dark. This is something that we forget about. Po Po is quite often taken out of time as if he existed out of time. Literary critics understood him that way for decades and decades that Poe was a man out of time. This to Poe would have delighted in. But in fact, the eighteen forties were known as the hungry 40s, this time of considerable starvation in the United States in the wake of the panic of 1837, the global financial collapse that devastated the American economy pose financial prospects, which were never good at any point in his life, were made much worse by the panic of 1837 and by the early 1848, he was down to his last quarter dollars. The sums of money he made for his stories, he never really made much for his poetry or really anything but the sums of money he made for his stories in the 1940s and working as a magazine editor patched his life along from here to there. And he struggled against drink and against his own depression and his darker instincts.

Speaker The blow from which he never really recovered came in January of 1847 when his wife died of consumption.

Speaker Most of the people that Poe loved died of consumption. In fact, if you pay much attention to American history, though, most of the people that most people loved died of consumption in the 19th century and so were childbirth. So you this does not distinguish Poe in some remarkable way. And I guess I would really emphasize and underscore that point. Much that looks romantic about Poe is utterly commonplace. It is the sad tragedy of human existence in the 19th century city. And Poe did much better than most in those circumstances. But in any case, the way the loss of his wife in January 18, 2011, was devastating to him, I think it’s impossible to know what goes on inside someone’s mind. And historians who speculate such a degree are sure to make mistakes. But Poe from his childhood, had been obsessed with the idea of mourning the death of a beautiful woman. He thought that was the most poetical form of grief. He thought that was the most sublime form of human expression so far from a kind of tempered down, up we go responsible the loss of a loved one. Poe delighted in that grief and sunk himself into it. He thought it was a beautiful grief.

Speaker Never more would be Virginia. And he drank and he made no money and he starved and he fell apart and he got worse and worse. And he was terrible to people and he was rotten to people. And he made himself miserable and made the people around him miserable. And he staggered to Baltimore in nineteen and he staggered to Baltimore in 1849 and got drunk and collapsed and then was apparently carried from polling place to polling place.

Speaker It was during the congressional elections. And Baltimore is notoriously corrupt. American elections in the nineteenth century before the rise of the secret ballot were notoriously corrupt. There’s not an election day before 1896 in which someone was actually murdered at the polling place. So it’s a violent, tempestuous, drunken scene, Election Day in American cities.

Speaker And Poe apparently was helplessly, probably unconscious, carried from polling place, polling place to cast many votes until he was finally brought to the hospital where he died three years later, presumably dissipated.

Speaker Thank you. OK, that was good. He died.

Speaker I know I was going to ask you just do it again because he said he died three years later.

Speaker Did I say three years ago?

Speaker Eventually, he was carried to a hospital where he died three days later.

Speaker Thank you. Well, there’s a lot in there. I’d love to go back and talk a little bit about where to start the cities, the way you talked about American cities in the 1930s and 1940s.

Speaker Can you talk a little more about what was going on on American cities that people now just don’t realize what was new and different? And how did Poe’s work? How did those stories particularly tap into that sort of general atmosphere?

Speaker Sure.

Speaker People like to talk of himself, talk publicly, talk about himself as unworldly from another world, otherworldly, and yet he was very much of this world, very much of the antebellum American economy in particular, what he like to present as his poetical and romantic impoverishment was a mere function of the economic devastation of the early 19th century. He was very much caught between what I think of as the and pendulum of the 19th century economy, the panic of 1819 and the panic of 1837 during both of those panics.

Speaker I mean, the economy was not regulated in any way. This is what the great political crisis of Andrew Jackson’s presidency was about, whether there should be a Bank of the United States and whether whether it should regulate economic activity, whether to regulate currency, whether there should be a gold standard or there shouldn’t be a gold standard. This was a big debate during those decades. What could we do as a government? The federal government wanted to know how to prevent these devastating financial panics that leave people starving in the streets, especially in the streets of the cities where people have gone to get work in factories. Factories are new. This is the early, early years of the industrial revolution in the United States. It started earlier in Britain, but in the United States is fairly new in the 20s and 30s.

Speaker So the federal government is having this big debate. What should we do with a debate between Congress and the presidency? What should we have a bank? Should we not have a bank? And it’s something that is affecting all Americans in all ranks of society. It’s something that Paul writes about again and again and again, as do many writers.

Speaker Paul was essentially a hack writer. He wrote stories for money. He lived off of his writing and almost no one did that. The only American writer of any distinction to actually live off of his or her writing in this area is James Fenimore Cooper. That was extremely unusual and also hated Cooper for his success, but resented anyone who was successful financially as a writer. And I suppose in the sort of paradoxical position, because he had very few resources, he he had essentially been disowned by his family, who’s an orphan. He was then he was disowned by his more or less adoptive family. And he also alienated himself from them due to his own just ill will and general misanthropy. So he was left with very few resources except for his mind, you know, and he sort fetishizes the great genius that was his mind that he could turn. He could he could turn his mind into a moment where he could just he could create currency. He could make money by the ideas in his head. And he wrote about this again and again. He played with this metaphor all the time that his mind, my mind is a mint. And at a time when people are really thinking about the meaning of money, it’s not it doesn’t. It just comes from Poe. I mean, if you just read Poe, absent American history and American economic history in particular, it looks like, oh, he’s such a startling, interesting genius, actually. Now he’s a man obsessed with how he’s going, how he can make enough money to feed himself. He’s very often quite hungry. And again, anyone who is working for a living, working wages, which is essentially a kind of wage economy that Poe is in, and he wrote about this as a kind of bondage Dickens did to Dickens, and he said, no man has is more bound than a man who is bound to a pen, is playing on the idea of a pen as a prison and writing implement. And Poe, of course, writes about pens all the time. And he wants to when he wants to find a magazine, what’s called the stylus. But before that, he calls it the pen he’s in. He writes this essay called the magazine prison House. I mean, these writers who are writing for money Dickens much more successfully than Poe, writing on a schedule that sort of unceasing schedule of magazine production. We think about how fast everything is in this digital age. And if you’re a blogger, you have to be posting constantly. But that speed up happened with the factory system and that transformation of just the pace of ordinary life. And the monthly magazine and the weekly magazine, which is what Paul mainly worked in the weekly magazine. Think about how fast you have to work in the 1920s and 30s and 40s, how fast you have to write and produce to put out a weekly magazine. You have to set each of those types by hand. You have to get that magazine printed. You have to get it distributed. That’s an extraordinary speed. It’s much faster than what we are doing now. Maybe that the magazine takes a week to come up. But given the given the technology that produced that magazine, that is exhausting work.

Speaker That is kind of sweatshop work. So when Paul talks about the magazine prison house, he can’t escape it because he needs the money. The money is very little and he also thinks that he’s much better than the magazine. So I’m so fascinated with, you know, a lot of people can’t stand Poe for this reason.

Speaker I think it’s funny. I find it very funny. I find Poe mainly hilarious. Very rarely do I find Post scary because I find the way he’s trying to scare you so funny because he’s playing with these popular.

Speaker Forms and what he’s always trying to do, and I just cracks me up, but I was always trying to do is say something really spooky to you and then go well and meanwhile communicate to you that he just thinks this is just beneath him, that he knows that this is kind of a trashy art form, that he is being the.

Speaker It’s a kind of like Joss Whedon humor, it’s a kind of Buffy the vampire humor, it’s a kind of genre play that is about I understand the genre. I actually enjoy the genre. I’m so much smarter than the people who work in the genre that I’m going to do a meta form of this show. I’m going to write a form of this of a tale in this generic shape that is a commentary on the shape of this generic tale. So all of his stories have these kind of things embedded within them that are about pointing out in a better economy, I would be working in a higher art. You know, my poetry is more meaningful to me than my tales, but my poems don’t make any money.

Speaker So I’m going to write tales. But I want you to know that really I’m a poet. And he he just kind of comes back at that again and again and again in his stories. And I think a lot of readers who are have a kind of a literary taste and who would enjoy more highbrow writers from the 19th century. Certainly Poe’s contemporaries found Poe to be this way. Find find that. Tacky and they’re sort of unforgiving of it, someone like Longfellow’s too kind hearted a man to be unforgiving of that. But Longfellow has married an incredibly wealthy woman and is just drowning in money landfilled who never has a money problem. He also is very successful as a writer and. But he’s not appreciative of what Poe is up to. He everybody can see through it, but. Some people find it just contemptible, and I know other people find it alluring and I often say it’s sort of like.

Speaker Is like The Simpsons, you can watch The Simpsons when you’re two and just basically like you’re watching Itchy and Scratchy and it makes you crack up when you watch The Simpsons when you’re 22 and you can see this when you like. I like I watch my kids, like, watch it. Then suddenly they get a whole level of joke that they, of course, never got when they were two.

Speaker They didn’t get what they got different jokes. When they’re five, they got different jokes when they’re 10. When you’re 50, the jokes are different. Homer looks different when you’re 50. Poe’s stories have that many layered feel to them so that readers could enjoy them just as their spooky stories. Readers could enjoy them as parodies of spooky stories, and then readers could enjoy them as essentially poetic essays about the spookiness of stories.

Speaker Yeah, that was too long, Vinnie. There is wonderful stuff there.

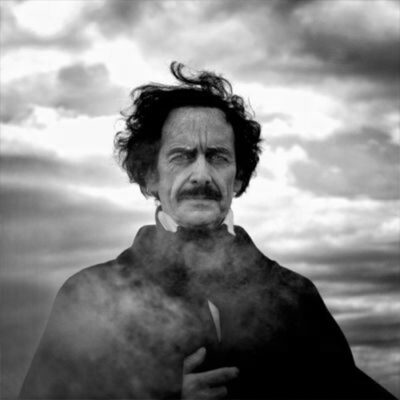

Speaker So getting to this issue of his own, his sort of condescension that you talk about, condescension to his readers, think of one element in our film when when Denis O’Hare as PO is quoting a letter I had written to somebody about detective stories about the success of the detective stories. And he says something along the lines of, I don’t really understand why they’re so successful. They’re just a novelty. And really, what’s the challenge to them of making something up and then solving it?

Speaker I mean, what was I ask my questions, if you could talk about that, why was he so dismissive of his own success?

Speaker I mean, he always over and over and particularly with the detective genre, he seemed unable to just enjoy the success he had to somehow undermine it. Well, I guess I would first say you ought never to believe Pearl.

Speaker He was a consummate liar, wasn’t a pathological liar, but he was a consummate he was very excellent liar. He consistently lied about himself above all things.

Speaker And so it’s easy to say that Poe’s legacy is complicated because of what was done to his papers and how he was perceived and abused by Rufus Griswold, but actually posts that most of that himself. By then, he he thought most biographers, because he leaves such contradictory records, a lot of Poe’s Daumier, you know, about his work and dismissal of his own work, his performance, of course. But he does actually have a great deal of contempt for his readers. Anyone who would read the kind of thing that his publishing and being paid money for is not worthy of his attention. So it’s actually not contempt for his work. It’s contempt for people who enjoy his work. They don’t actually understand it as well as they ought to because I think what people believe. So maybe that comes across as kind of projection upon himself, but really it’s contempt for his readers. And I think that does come across quite clearly when you read the work carefully. What is so, I think, beautifully brilliant about the creation of the detective fiction genre in the way that Poe creates it, is he inhabits that contempt in the story in a character that he creates in the character of August dupatta.

Speaker And, you know, this is if you’ve never read the home to pass stories and you just only have to have read Holmes and you know the character because Holmes is a rip off of Dupere and so is pretty much everybody else. So is Nero Wolfe.

Speaker So is a Kupwara. So is your house on television. These characters are all derived from Dupere because these were the conventions that Poe established and it was the way that Poe reconciled his misery, which was that he was he thought he was devastatingly brilliant.

Speaker And yet he was shackled to this popular form of the magazine Thriller and the way he attempted to unshackle himself or at least kind of. Linger over the beauty of his shackles, which would have been more of a powerful thing to do, was by creating a character within the stories themselves who is devastatingly brilliant and smarter than everyone around him and can see through everything he can.

Speaker He can he can see a man’s chest, man’s heart through his chest. There’s nothing that he misses. He can read writing that is written in a secret code.

Speaker He in the same way that, you know, Holmes walks in the door and he meets you and he knows that you’re the fourth of five children, that you’re you smoked a tobacco pipe containing tobacco that came from one province in the southern western part of India, and that you that morning had pheasant for breakfast, that Dupin knows these things because he can see and perceive a layer of complexity and a level of detail as observational skills and skills of acuity and deduction that are lacking to those around him. This was Poe’s way of being a character in his own stories and DuPont’s relation to other characters in those stories. That is the same that is identical to the relation that Poe had to his readers, which is to say, I can’t really even be bothered with you people.

Speaker You’re just so deft, you know, and he had a great deal of fun with that. And it is actually fun to be duped.

Speaker I mean, that is what Dupin is. He’s duping every everybody is is a dupe compared to him. So both took a great deal of pleasure in that. And I’m sure that he did. But then part of that, it would be a necessary part of that move, right. To say this is just meaningless dreck. Right. That that would be what Dupin would say. You know, you mere mortals who think these stories of mine are wonderful. Well, you don’t, actually, because only I only I really appreciate what is great.

Speaker Thank you. Yes. I don’t.

Speaker Hey, can I can we let Leon help? Oh, yes. Yes.

Speaker She’s sitting outside of the tell tale heart a little. I mean, to me, that’s one of the stories that seem to be playing neighbors. They could be murder.

Speaker Yeah, yeah, yeah. Kind of thing. And but it’s also got the boot factor, of course. Right. That makes sense.

Speaker Yeah, yeah. Yeah. OK, know this is Lee. This is Jill. Right.

Speaker Yeah, yeah, so. All right, I’ll ask a question, but don’t feel like, OK, unless you are ready to talk.

Speaker But no, I can talk. I can talk. Um.

Speaker In many ways, the early 19th century was the great age of anonymity and really possible for the first time for people to reinvent themselves altogether, and that had to do with industrialization, but especially with urbanisation, people moving to cities from from towns where everybody knew who you were, who your family was, where you lived, what your father did, who your mother knew before she knew your father, your entire life story, that small village feeling that many people still have. But if you have that as a kid and you move to a city or you go to college and you were a new person and you can you could even rename yourself, that was new in the early 19th century in the United States, cities were growing at a phenomenal rate and they were especially filled with young people. And above all, they were filled with young, unattached men who’d moved to cities to do wage labor women, to some degree, to other women like the the the so-called girls who worked in the Lowell Mills. Eighteen 20s and 30s, they lived in they boarded in factory housing. So they weren’t sort of adrift in the city. But if you were a young, single, unattached man who moved to the city from the countryside to to work as a clerk might be what comes to be called in the 20th century. White collar work wasn’t called that, then looked to work as a clerk or to work in a factory you boarded in a house. You could be whoever you wanted. There were no fingerprints. There were no identity cards. There were no vital certificates. There were no birth certificates. You could tell anybody anything about yourself and you could invent yourself. This was a source of both tremendous excitement for many people and a profound cultural anxiety.

Speaker You see this anxiety expressed all over the place in the United States by the eighteen thirties and certainly in the 1940s. There’s a lot of fiction about it, like post story, the man in the crowd where it was just about just you you know, you just this guy just walking through the city and no one knows who he is. And there’s that. That is who everybody is. No one knows who you are. And there’s a great deal of anxiety in those antebellum years in cities, for instance, about masturbation. This is when the Sylvester Graham anti masturbation crusade happens, because Sylvester Graham, who’s a sort of health guru, starts preaching that what happens when all these young men live not with their families and they haven’t formed a new family yet?

Speaker Well, they’re just sitting in these boarding houses masturbating all day and they’re going insane. And so we need to, you know, we need to send them to insane asylums or we need to lecture. So men would go to edifying lectures that would be kind of reformed. So all the reform movements that you associate with 18, 30s and 40s, the temperance movement, for instance, this is about middle class families. The middle class is created by industrialization.

Speaker This is about middle class families trying to discipline these stray vagrant men, unattached men also disciplining the working class. But there’s a lot of anxiety about about these men, so. Who are they, are they are they to be trusted? You don’t you only have what they tell you about themselves. It’s a little bit like the anxiety about the worth of paper. Right. So at that same time, when the economy’s just going nuts up and down and up and down and up and down, there’s no stability to the economy because I can give you a piece of paper that says this is 20 dollars and it might be from a bank that has collapsed and you have no way of finding that out. The value of paper, the fluidity that the impossibility of judging the value of a piece of paper is is wreaking havoc. It’s you know, Paul writes about this again and again every early 19th century writer writes of so many people who don’t understand what is the worth of paper. This is posed great anxiety. What is the worth of what I write on a piece of paper?

Speaker But the same thing is true about the credentials of a person. I give you my papers, like when you go to here’s my papers, I have a letter of reference. You know, this is someone saying who I am and people carry on these letters of effort to introduce themselves. But. But you didn’t really know the paper could be a forgery. So think about all the anxiety about forgery and the theft of the purloined letter, the theft of the letter, people opening other people’s mails, this great anxiety, this very same time. Right. Because this is what connects you to other people. What is the authority that marks who you are and what you know and your credibility is contained on pieces of paper. So all of these wonderful elements in.

Speaker In a kind of chaos of meaning, just to just to calm ambiguity of meaning.

Speaker Yeah, OK. All right.

Speaker OK, now, right, OK.

Speaker So, yeah, so you have all this ambiguity of meaning, what is a piece of paper worth? What is a coin worth? What is a man worth worth? Where does truth lie? Who can be trusted? Which is great fodder for scary stories, right? It could be because strangers are scary in a different way. No matter what I tell you about myself, you have no way to find out. I guess you could send a letter to the person. I said I knew me in some other town that would take weeks to come. That this is even before the telegraph. Right? So this is there’s not letters.

Speaker The only way you have a way of gaining information about something and letters can be forged and letters, envelopes can Steeles on envelopes can be broken. So this is kind of great age of of of anonymity and of mistrust fulness.

Speaker So you see that in post stories. It’s just so easy. It’s so easy to play with in the telltale heart sky because living with this, you know, living the old man and taking care of him.

Speaker Well, actually, he’s losing his mind and he’s plotting the murder of this old man. And who’s to discover whether he’s murdered the old man or not. He would not be discovered were it not for his own insanity, which reveals him to the police. The police don’t figure out that he has murdered this man. He reveals himself because he can’t stop hearing the beating heart. You later have Dupin, who would have figured that out? But here you just have the manifest of the body itself. And that’s Poe who’s figuring it out. That’s Poe being Dupain. I can see that heart beating.

Speaker All right.

Speaker The public appetite for those stories, so was this new and different? Was there kind of a spike in the appetite for sensation and real crime and the things like the Penny Press and the.

Speaker Yeah, well, one thing to remember is that. The literacy rate has skyrocketed. One of the things that happens when Americans move to cities and factories are built to begin working in factories before the 1820 is, there is no public schooling in the United States. There are no sort of formal public schooling. But there’s one of the reforms that happens when the new middle class kind of looks around and says it’s a lot of instability in our economy. This could be dangerous. There’s a decision to start offering free school. It’s called the common school movement for the children of factory workers in particular, to provide them with an education, to make them better workers to discipline.

Speaker This is the thing that is always said about the American school system, even today, that it is essentially a way to prepare children to be factory workers. It’s about the regulation of the routine, learning how to work by a clock. It is about the disciplining of the human body to function in a factory. Kids will complain about the sickening. If you tell kids this, it’s the worst thing because then, oh, that actually explains a lot about my school day, why I never understood why my school day was so ridiculously rigid. But if if that if the school system started in the 1920s as a way to teach children how to work in a factory makes a lot of sense in any case.

Speaker So there’s schooling and people are going to more people know how to read than have ever known how to read before things, including girls, which is new.

Speaker There had been these this new form of the mystery, the Gothic mystery that started in the 70s and 80s, really even even a little bit earlier in England, and these Gothic tales are.

Speaker You know, these sort of like the Anne Radcliffe story is like the mystery of Rudolfo, that these they’re they’re set in the Middle Ages, which has newly has this romantic cast to it. And it’s this this is a long history of why that would be and what has what that tells us about the Reformation and about the the Enlightenment and why the Middle Ages suddenly look like a place that you could go to poach for something scary, because they’re they they predate the rise of the age of reason. And so there’s not reason back there. And there’s there’s mystery back there.

Speaker So there’s this whole new form, which is the mystery. And it’s dark and it’s it’s spooky and it involves castles and it involves secrets. And this is a new literary form that the middle class first pleasures on and then begins essentially making fun of.

Speaker So by 1818, when Poe is living in England with his stepfather, has brought the family to England because of his own financial struggles.

Speaker In 1818, Mary Shelley Frankenstein is published on Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, published, both of which are both part of that new genre of the mystery. But they’re really at the tail end of it in some way. They’re both making fun of it. And Frankenstein is spooky. But it is actually also kind of a brilliant send up of the genre. And it’s sort of like, you know, the great story of Mary Shelley writing it, you know, just as a as a lark on a weekend with Bilic, who can write the spookiest goofiest thing. And it was all put in everything. I’ll have a monster. And I have this side, you know, these these things that have become become stark but are also drawn from old stock. And, of course, you know, Austen’s Northanger Abbey just is a satire of the entire form. So the the form really, by the time that Poe becomes acquainted with it, has utterly gone to seed. I mean, it’s just it is actually pretty trashy. And that is what Poe is both drawn to and appalled by about it. It’s trash. It’s like a piece of paper that is has no value. It is literally trash. And he it is it is worn thin, like there are these pulp magazines that people buy. They have very wide circulations. The stories are utterly formulaic. They have this, you know. Well, it’s going to have this and this and this and this checklist. And this is hilarious. How to how to write an article for Blackwood’s magazine publisher, these things where it’s just like, OK, you need a corpse in a coffin, you need a castle, you need a doctor who’s going mad. You need a beautiful woman who’s dying or dead. And so when Poe begins writing these things, they have this completely campy feel to him. They have a completely campy feel, and yet they still pass the thing itself.

Speaker Was he really trying to take I guess I would guess that you could take a couple of those stories from unknown contemporaries of POWs and pass them off as POWs, stories without too much difficulty.

Speaker There is a sophistication to what Ho is doing, and the dupatta stories advance the form and take it in really quite a different and exciting direction.

Speaker I guess maybe there’s a little bit more intensity to some of the POWs stories is a little bit more psychological, sort of believable psychological drama in something like the fall of the House of Usher.

Speaker But some of those magazine stories are pretty damn good. And not just POWs, but some, you know, by unknown hack writers in a sense that they it’s kind of a checklist. So it’s not it’s not that hard. I mean, it it’s hard. It’s not that hard. You know, it’s sort of like, you know, Louisa May Alcott character Jo in the beginning or she writes these stories to like it just it’s just a thing to do. It’s not that hard and it’s hard to do it exceptionally well, but. It would be an interesting experiment to take a bunch of Poe’s stories and read them alongside a bunch of contemporary tales and see if you could really tell what Seppo apart and be a fun thing to do.

Speaker And yet POWs have lasted. All these others have. Yeah, yeah, although.

Speaker You know, I mean, I love power, so this isn’t meaning to diminish power, but.

Speaker Plenty of far more talented writers are forgotten all the time, they’re not as widely published. They don’t become canonised for one reason or the other.

Speaker We forget that people who are in the literary canon today were put there quite specifically at certain moments in time. So. You know, Dickens was considered trash his entire career. Really? He was only. Elevated to the ranks of, you know, he’s as important as Shakespeare, decades after his death, Melville really was a fantastically unsuccessful writer and also not much esteemed until, you know, Newt Norman and Ethel Matheson decided that he was a really brilliant and important iconic American writer.

Speaker And they just utterly reclaimed him, the women’s writers of the 19th century that are now quite widely read and taken seriously for the way they contribute to the form of the sentimental novel or for the implicit political critique in some of their writings, not just a, you know, Harriet Beecher Stowe, but some lesser known women writers to, you know, were brought into a canon that was created by feminist literary critics in the 1980s.

Speaker Who we care about is not altogether a mark of. Whether they are worthy of our attention.

Speaker Let’s talk about pose a critic, as a literary critic, as a reviewer. You talk just briefly about what his reputation was and how he how he saw himself as a critic and how his self-importance.

Speaker Yeah, but also I’m curious about how he revealed women writers, whether he revealed them differently than some of his contemporary male contemporaries.

Speaker Yeah, I think Paul thought of himself first and above all as a poet. Next, as a critic and only after that as a. Storywriter, he was a failed novelist, didn’t give a novel writing much of a crime novel, writing was a long term economic investment. He couldn’t afford to write novels.

Speaker But criticism was whelping was a big part of his editorial duties at any magazine that he worked at as a either as a contributor or as an editor and was good at it. He he was an astute and keen reader.

Speaker He he was learned without having a kind of fake erudition to his prose. He was very readable as a critic. And he was a fierce critic then, almost all of his contemporaries. So if you remember this moment in American literary history. Before the American Revolution, Americans really only reading English writers, there are a lot of American writers except for Benjamin Franklin, who soars above all the rest after the revolution. There’s a real push for American nationalism. We should we should produce and read our own books, sort of, you know, Emersonian young Americans sentiment. And so there’s a lot of enthusiasm for Cooper, for Jimsonweed, because he writes he’s an American writer, but he writes in a distinctive American way about distinctive American subjects.

Speaker He saw his moccasin clad Natty Bumbo trudging through the forest. This is what could be more American. It’s Western.

Speaker And a lot of American critics have the idea that you essentially would say that you you can’t criticize an American book because we need to celebrate American writing, because we need our own literature in order to invent an American literature. We can’t afford to denigrate any American writer. And so, you know, poets say the whole point of these reviews is, is to celebrate stupidity if stupidity is American. And Poe refuses to participate in this now. I have real soft spot for Poe here because he considers himself the consummate outsider. Like there’s this is if there’s this Klan as Boston based and it’s James Russell and it’s Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and to some degree it’s Hawthorne.

Speaker And then there’s also Washington Irving. And then there’s the northerners. They’re all northerners. Most of them are New Englanders. And the worst of them are from Boston, where Paul was, in fact, born. But he’s really a Southerner. So he hates these people and he believes that they they both sneer at him, which is true and also not true.

Speaker Again, you know, someone like Longfellow’s quite a generous hearted man and I think quite admired, honestly.

Speaker So in spite of Poe accusing him of plagiarism left and right, this is Poe’s favorite things to use because people to the polls just you know, he’s ornery and he prefers his preferred poses that of resentment he had. He enjoys resenting people and he feels that he’s been he’s he’s not gotten the right chances. He just begins from this posture of the sort of moody, sulky, resentful. That’s really and his criticism precedes from there where it succeeds is when he rises above that and actually is just he’s very smart. He’s a very smart critic. Um, where it fails is when he’s petty. That’s that is the person who is going to write a petty review where he’s picky about the most meaningless nonsense, where he doesn’t understand the scope of the work, where he’s so busy resenting the success of his fellow writers that he can’t begin the process of evaluating the merit of their work. So someone like Dickens, who is adored by American readers but not much respected and certainly not much respected in a lot of ways and other in the United Kingdom or in Britain.

Speaker Poll finds much to applaud and Dickens’s work, but less after Dickins proves unhelpful to him.

Speaker So here you just see the kind of the rivière whose whose resentment and pettiness defeats his purpose.

Speaker And in during the 1940s, when he’s in New York, forty four or forty five, forty six and riding a lot of criticism, he’s reviewing women writers.

Speaker Yeah, you know, I remember reading about that, but I don’t know that much about that.

Speaker Um. Sorry, I just don’t feel sorry for you bounce around this time.

Speaker That’s OK. So New York City in eighteen thirty seven when he leaves Richmond, leaves the Southern Literary Messenger, arrives in New York trying to be the, you know, the big thing in town. And you write so well in the article lands at exactly the wrong moment. Can you just talk about that moment when he gets to New York with all these high hopes and what happens?

Speaker Yeah, um.

Speaker The scale of the panic of 1837 is difficult to reckon with, except as against panics that we know better.

Speaker They’re called panics then, but they really are collapses. So 2008 is a pretty close approximation. It’s a completely different economic system. So it’s a crap analogy in many ways. But if you think about the suddenness of that collapse, I mean, there were moments where in Congress they were trying to decide if we don’t do this, the world will implode like the sky is falling kind of feel. And in 1837, just when people arrived in New York with this very high hopes and maybe at the height of his literary ambition and in some degrees of the height of his success. The economy collapses. I think something like four out of five factories in New York are closing the lines to get jobs just for day labor for the most measly of sums are around blocks and the sense that. What has led to this devastating suffering where people are actually collapsing on the street from starvation is speculation is hard to bear. There’s no one to sort of there’s no external cause to blame, maybe even less than there was in 2000.

Speaker It was sort of I hate Wall Street, Wall Street responsible. Those fat cats on Wall Street. There’s that then, too. There is Wall Street then, too. And there is that that sense that these panics, you know, the first one in 79 is that these are caused by Wall Street. But but that it is speculation itself, the act of speculation, the necessary act of speculating on one success, which is, of course, will pose himself doing his speculating on whether he can succeed, that that that that is a force not for good, but also not only for good, but sometimes for evil. And then we have no one to blame but ourselves. So there’s this double darkness of that kind of a financial panic. Right, because it’s terrible and people are suffering.

Speaker But it’s our fault, it’s it’s it’s the system. I mean, this would be you know, there’s not this is where Marcus comes from, right?

Speaker This is this is why Marcus writes the Communist Manifesto.

Speaker This is why communism as a theory of understanding emerges because Marx Engels looked at this kind of suffering in the world that they inhabited in the cities in which they live, the very same suffering that POSA and they decided that capitalism was was wrong, was ethically indefensible. There’s not that same there’s not the purchase for that set of ideas in the poll in the New York, the pollution in 1837. But there is the same intensity of misery.

Speaker And can you talk about what personally, I mean, that’s one of them living on bread and molasses for weeks at a time, and can you just I don’t know if you can maybe you don’t have the details at hand, but just describe what it would have been like for Paul and his little family is what by then 14, 15 year old wife and mother in law.

Speaker Yeah, no, no, no, no, I don’t quite know the details.

Speaker There is for Paul.

Speaker And for everyone whose papers you read. People have been brought low by financial speculation, by the panics that are just closing factories and depriving people of any source of income whatsoever.

Speaker Where do you go in a city when there’s no work in a factory, when your clerkship has ended, when the magazine you write for is folded?

Speaker What do you what do you do? You can’t go out into the field and.

Speaker Would you find you can’t slaughter an animal so people do just starve in the streets? They stand still and they starve where they stand and it is moving to see people right about that in it, it finds its way that suffering in that darkness and that misery, it’s that suffuses a whole culture. When that happens and you see it in Poe, the way it manifests in his stories.

Speaker And you can see, I think there would be a way to read something about the dead or the near dead being brought back to life. That is a lot of that animation and reanimation, the cyclical nature of the American economy.

Speaker There’s a this is an upset like can we be reanimated? You see people being described as skeletons. You know, there are anatomy’s walking down the street like anatomical skeletons. And so when Poe sends out his stories, you know, he is just one letter. We’re sending out a story and he writes to the editor, you know, here’s my story. Here’s how much I’m asking for it published here. Here, the same cover letter that you would send as a writer.

Speaker Normal query. And he’s written in bottom piece, I am poor.

Speaker And, you know, as opposed to the gentleman writer, that’s not as opposed to everybody else in the city. Everybody else in the city is working for wages, is poor.

Speaker But Poe as a writer is unusual because we have, you know, your James Russell laws and whatnot. Poe is poor in a different way than those than than most writers are.

Speaker All right. Thank you. Um, gosh, we covered so many things in different ways. Rufus Griswold, so when he meets Griswold in Philadelphia, this would be about 18, 40, I would guess. I don’t know exactly. Who is Griswold and why why is this such a fateful encounter? Do you have someone playing Griswold in the thing? No, we only have one actor we lampo. Yeah. So it’s a one man show.

Speaker I can’t remember what it was. He’s a fellow writer and he was a writer editor at Grammes.

Speaker He was all over the place to replace Poe as editor of Grammes.

Speaker Yeah. And he mostly was an anthologist. So he was putting together the poets and poetry.

Speaker And of course Poe wanted to be in it. And I mean, we if you don’t feel.

Speaker Comfortable doing that, we can we can skip that, um.

Speaker I don’t know, I can say some stuff, and if you fact check it, it it’s wrong, you can take it out, OK?

Speaker I just don’t want to be wrong because my kids, we won’t let that happen. Doesn’t look good for any of us.

Speaker Yeah. Yeah, I know. That’s what I’m figuring. You would be doing some fact checking and um. So, Poppo.

Speaker A great deal of what mattered was earning enough money to live. That’s what mattered above all, and that was hard. But in a deeper sense, what mattered to her was recognition and the esteem of all of those sort of fancypants smartasses in New England, in New York, who were in charge of who was a good writer and who is not a good writer. And there were people who made their living figuring that out.

Speaker And critics weren’t especially good at that because they were welcoming and they didn’t want to be too critical.

Speaker And who was greatly critical of this?

Speaker That they’d all criticism was puffery and it was and therefore you could never know what anything was worth, which was a cause of great anxiety in a world where you couldn’t know what a piece of paper was worth, including a dollar, you didn’t know what a dollar’s worth because you didn’t know if there was money in the bank to back it up. If someone, you know, published a poem and a critic was unwilling to say this is a good poem or a bad one, but all criticisms, some said, oh, it’s American, therefore it’s great, then you couldn’t know its worth and that that ambiguity was a problem. But nevertheless, he wanted people who were desperate for the approval and recognition that would for him be a kind of redemption and think about the force of redemption, metaphorically, in a world where money and the value of money in exchange is is the obsession is the metaphor. Everybody is working. So Paul was always keen to be redeemed.

Speaker And when he really wanted to be redeemed for a known for his poems.

Speaker So this is part of the source of his everlasting and fateful encounter with Rufus Griswold, who was a contemporary and also a writer, but he was an anthologist and Griswold Griswold was a great puffer.

Speaker Poe would have said, if you puft Griswold, Griswold would puffier this this log rolling. And we know it very well. And you see it in the pages of our nation’s newspapers and magazines all the time.

Speaker It was very much a thing then Poe had this kind of piety about it, like he wouldn’t have anybody and he didn’t expect to have them because he thought that there should be real value. If you were going to say someone’s work was good, it shouldn’t be because they knew that they would say you’re good. Pulpo is the kind of guy who in his day would not have written a blurb, you know, because he didn’t believe in blurbs when no one would ever write him a blurb and then he would hate everybody for it. So that would be fun. So this is kind of his relationship with Griswold. And when Griswold sets out to produce an anthology, The Poets and Poetry of America. Poe is enraged by how he just he’s you know, he thinks the whole thing is utterly corrupt, as doubtless it was Griswold was I guess Griswold was quite a that would be going too far. But Griswold really wasn’t asked. I mean, he really was so Griswold’s and we have this adversarial relationship that becomes fraught and more complicated by Griswold’s fixation with power. And it is a problem for pope biographers and for anyone really trying to understand Pope that after Poe’s death in 1849, in a fantastically ill considered decision, Poe’s mother in law, Maria Klemp, sold his papers, his literary remains, what we would call the remains of Edgar Allan Poe to Rufus Griswold, his arch nemesis.

Speaker And the very first thing Griswold did when Poe, Don, was like just one of the all time most mischievous, devious and mean spirited obituaries sort of ever like I’m trying to picture who could write such a mean spirited review. Meanspirited obituary in.

Speaker I always like to be like. Kissinger writing an obituary for Benjamin Spock or something like just people who are just completely opposed and had really opposed one another in a significant way, the person who you know, when you’re asked to review a book, you’re asked, do you have a conflict of interest? And if you have a history with that person, you have to say, I do. And it might be that you’re best friends, but it might be that you have actually had a fractious like he he has reviewed your work before. Griswold is like the last person any editor should have assigned an obituary. Edgar Allan Poe, too, and the very last person that claim ought to have sold his papers to.

Speaker It is, and it’s very hard for us to get the relationship in the film in a way that makes sense. Yeah, yeah.

Speaker And I think it’s you know, it’s easy to make too much of it, too.

Speaker It’s not, as I say, I think the most complicated legacy as opposed to the goldbug 1843, because I love your section of the article.

Speaker Did you talk to Mark show him. My only concern about talking about the book is a lot of money.

Speaker I mean, I love this article that he wrote about the goldbug, and I credit that here and the essay. But it would be harder to, you know, to do were for you to decide to keep it OK.

Speaker And it’s a I think that’s I think that’s just a tricky thing to do. Sure. I mean, my reading of the goldbug is different than Marx, but it’s very heavily indebted to it.

Speaker And I would want to be careful of the expose your name to the magazine.

Speaker I married, of course, our film’s chronological someone. So we try to keep things to various periods. But could you talk a little bit? Are you changing tape, say, OK, you talk a little bit about minutes when he first starts to want to have his own magazine?

Speaker Why what what’s this hunger for his own magazine about? And how realistic an ambition is that for?

Speaker Yeah, I think you would maybe guess off the top of the bat, I guess. I think you would maybe guess that would not be an especially good businessman. So you’re investing in a magazine would be difficult person to invest. And you might admire his work immensely, but he was not a steady young man. So I, for instance, would not have made an investment in the magazine.

Speaker And he won among the reasons he wanted to start his own magazine, rather ordinary ones of an aspiring young writer of independent views who don’t like being answerable to an editor magazine. Writing is incredibly demanding. It’s frenetic, and there is very little room for error because of the pace of it. The pace of a weekly magazine, again, which is super fast in a way that’s hard for us to read. And we think of life as slow and. Casual or something in that era, as opposed to our frenetic pace, our frenetic pace is nothing. It’s very physically grueling.

Speaker And for, you know, for people to say you’re a writer matter if you’re posting every day or tweeting all the time.

Speaker It made may feel incessant to you, but and it is kind of a nuisance feel to it, but it’s not like the kind of grind of Grub Street writing, which has a kind of physical intensity to it. And again, you know, Paul talked about it as being kind of prison and so of Dickens and so did many other writers.

Speaker So surely those people wanted to run their own magazine. The level of fantasy, largely. I think Dickens did run his own magazine. So this was in some ways a kind of. How you knew you had arrived was when you moved from being a writer to being an editor and then from an editor to being a magazine owner and publisher, and that’s that’s what I aspire to. He also.

Speaker He like to say that he left this or that magazine due to ethical conflicts, that he was smarter than his editors editor wanted to make his pieces stupid or his he and his editor had a disagreement about which book should be reviewed or his magazine wasn’t good enough for him.

Speaker Maybe he lost his jobs because he was a drunk. So when Paul says he wants to start a magazine, suppos not very employable.

Speaker When again, bounce around time than I did when you had mentioned this in the essay, when he left the Southern Literary Messenger, which was really his first real job as first important magazine job, why did he leave the Southern Literary Messenger with.

Speaker I don’t know. I mean, I can look it back up, all right, now, you quarreled with them, but that’s OK. So I need to change as well.

Speaker Oh, why do you have to leave his first real literary job in Richmond?

Speaker What was going on about Posadas, an editor for the Southern Literary Messenger, which is a monthly magazine, and you might think he’s arrived. This is the work that he was meant to do. It’s the source of steady income. He’s newly married. Who? His tiny little child bride.

Speaker And yet he only holds a job for 15 months. He said he left because he quarreled with the editor. He said that he was too good for the magazine. He wanted to move on for sure, but he didn’t get along well with anybody really for long. And so when he went to New York in 1837. He was hired by Rufus Griswold to work for The New Yorker magazine, not The New Yorker that was founded by Harold Ross in 1925. But Rufus Griswold is a New Yorker, which was a weekly magazine. So a real change of pace. I put that in there to lead into my peace thing.

Speaker Yeah, that’s good, actually. OK, so the pace thing that did make me think of a question, not on the list PO and one of his marginalia comments or one of his scribblings somewhere talked about how how magazines, you speculative magazines are forcing people to think differently, to absorb facts differently, to absorb information at a faster pace. I mean, I don’t know if you remember that at all, but but, you know, you’ve touched on this. But if you could talk a little more about what magazines were doing to the way people got their information, what their news and how it got there and how people just intuited it, or whether he was smart enough to realize it and how he both helped create it, but also helped or tried to profit from it. Yeah.

Speaker So the history of magazines is actually quite fascinating, the first magazines are in England in 1720 Gentlemen’s Magazine and The Spectator and The Word Itself magazine.

Speaker It’s a military term. It means a military arsenal. A magazine is filled with pieces. It’s where you put your pieces like a gun is a piece, you know, like in a kind of Raymond Chandler way. Look, he’s got a piece on him. That’s a piece. It’s a gun. So a magazine is where your store is an arsenal, where you saw your pieces and the metaphor survives. We still call magazine pieces, pieces. We’ve forgotten that they are an arsenal. There are weapons there. And they they are where you you gather together and you store your arsenal was the metaphor was to an arsenal of knowledge. And the first American magazines, which the very first one is started in Philadelphia. Benjamin Franklin wants to start the first American magazine in the seventeen 40s. And his rival, the printer Bradford, starts his like the week before and says the American magazine.

Speaker So Franklin has to call his the general magazine and neither of them last very long because the idea of a magazine is that it is a bunch of pieces that will save you the trouble of reading all the books from which the pieces come. And there aren’t enough American books that the Americans are not writing books in seventeen forties. And so all they are left to do is use pieces from English books that people probably already have or may not be as interested in. So it’s very difficult for magazines to succeed in the 18th century. And what becomes the United States even into the 17th is no. Webster starts another American magazine and it too feels I think it lasts like two issues or something. They’re really difficult to produce, partly because just a lot of text to put together in a short period of time. And by text, I mean actually the material themselves, like what are we going to publish?

Speaker So Benjamin Franklin’s niece, nephew, Benjamin Meakem, who’s the son of James Franklin Benjamin, Sister Jane, he starts a magazine in Boston in 1758 called the New England Magazine.

Speaker And it’s the New England magazine for knowledge and pleasure. And that is the whole idea of a magazine. It is for knowledge and pleasure that it will diffuse knowledge to a wider group of readers than a book because people kind of books are expensive. Not everybody can buy books. Magazines will be cheap, but they’ll be more expensive than newspapers and they’ll come up. At first they were monthly or monthly and it would be a way to just see what everybody else knew who actually read books. So one thing’s one of the things that magazines create is the book review. That is a creation of the Edinburgh Review, which is an early magazine. And they say, I know what a magazine could do. We could print reviews of books so then people could know what books to buy or else they could just read the reviews, which is, of course, what most people do. And at first they thought this is pretty interesting. They thought, oh, we’ll have we’ll review all books because they’re not that many books, really. I mean, there’s a lot, but they’re not that many. And first they did. But then magazines become selective and they try to figure out what books should be reviewed. So by the time Paul enters the world of magazine writing in the 18 thirties, magazines are newly successful.

Speaker First of all, they’re American. Magazines are successful in a way that they never were before because there’s enough American writers to contribute to them. There are enough American books to be reviewed and there are enough American readers, which is brand new.

Speaker There are also enough American writers willing to work for almost no money, which is what was not the case in the 18th century. So people remember this is a really struggling economy. People who want to know what’s what in the world and learn about the world, can’t afford books, don’t want to buy books, buy magazines to figure out what books they should know about. And magazines have a new role because they they don’t they can’t review everything. So they select.

Speaker So then that anointing role that magazines play, what gets reviewed and what doesn’t. Magazines are essentially each issue of a magazine is an anthology that has the anthologist power to say you are worth publishing, you are worth publishing in your book was worth reviewing. So this incredible cultural power at play here. And PO wants that power and that’s among the reasons that he wants to have his own magazine.

Speaker Doesn’t like what his editors when his editors say this, is that too often say your reviews are too scabrous and your stories are too nutty.

Speaker So Poe is left to try to figure out how to please his editors, which is a way of saying how to please the reader. It isn’t like the reader. He thinks these are stupid people. He’s really stupid. He’s smarter than they are. So he’s always trying to figure out, here’s this new form that has a new reach printing, printing presses gotten better and paper manufacturers better.

Speaker Magazines are cheap. This huge audience of new readers have been through. Common schools can read, I want to read something cheap and they wants to tell them what to think. And he wants to delight and scare them, terrify them. And he doesn’t have that sort of Benjamin Franklin.

Speaker He wants to diffuse knowledge. That’s not his thing. Was not an educator, and he’s not really an entertainer, but he has a.

Speaker He wants to show off, it’s probably what he wants to do, but the magazine is a complicated form for him because it’s so it’s so popular. So any way he can get paid. But it but but he needs to he’s you can see this story by story. He’s called recalibrating and recalibrating, you know.

Speaker Oh, this is this is this is too lunatic and this is too erudite, but that is not lunatic enough and this is not clever enough. And he just keeps jiggering and rejiggering and rejiggering his whole career, trying to figure that out.

Speaker You know, that famous famous quote, the whole trend of the era or trend of the Ages magazine where it said in the letter, I’m OK, let’s keep moving along, because you probably I have to pick up kids and. Yeah, yeah, let’s get to a couple of general what I have under the general heading here, which I think you are somewhat, but, um, so, uh, well, actually done almost all of us.

Speaker Well, let me ask you this, the films wanted to film starring D.W. Griffith made a film, Edgar Allan Poe 1989, I think, and then did one on The Raven right from the start was this magnet for first cinema as well as for visual artists, painters, filmmakers. Why? What is it about Poe that draws? All these artists from other genres, other media.

Speaker Well, look.

Speaker A biopic about Nathaniel Hawthorne, how good is this not a good story. It’s the woeful misery of his life and the tragedy of his death that is, first of all, appealing. It’s his Byronic presumption and pretense that is secondarily appealing. And the stories, by the time we Griffith’s many films, you know, they’re just they’re really well-known. Everybody reads Poe. My dad didn’t have a lot of books, but he had a collective set of stories that he I think it was an armed service edition from the Second World War.

Speaker People just read Poe and they were very delightful.

Speaker So it has a it has a currency. The stories I think the stories get better over time because they are removed from their time when I read them as a historian.

Speaker And so I read The Tell-Tale Heart and I think about urbanization and anonymity and I think about urban housing, vernacular architecture and I think about innovations in surgery and I think about the history of science and medicine in that period. And it seems kind of predictable to me. But if I drop that guys and just read it as then, oh, it’s really it’s just a delightful little tale and.

Speaker That guy that got the guys is strap for most people, I think the longer we go from the eighteen forties, the more mysterious the stories become. That’s well, whereas for other writers. And being here was my counterpoint, Hawthorne just looks more antique over time. We haven’t carried that form forward. So a Hawthorn tale is a Hawthorn tale and it feels to us like something that was written in the eighteen fifties. I think if you read a Hawthorn tale, you just know this is it’s set in time in a deep way. Certainly. Cooper or. Harriet Beecher Stowe or Longfellow, Washington Irving, these are all people who wrote about the time in which they lived in a very explicit way, Poe was always playing with timelessness.

Speaker He was always in it for the long game. And so he because he was so obsessed with being ethereal, he wanted the stories to have that ethereal, timeless quality. And if they ever set in a time or place like the House of Usher, it is an unbelievable place. Right. That’s the thing he’s importing from the Gothic. And so. D.W. Griffith would be delighted to set tales in the Gothic, as you know, in a medieval kind of Gothic setting as well, that carries it through town. It’s it’s it’s it’s nonsense.

Speaker Like, again, like this is sort of my point, but it’s nonsense to think that Poe is timeless just because he was using a form whose whole pretense was.

Speaker It’s timeless, though. That’s actually very timely. He was he was more shackled to his time than any other writer that we read today from that era. But it’s harder for us to see that.

Speaker I’m flashing back way back to young Po, young Po and John Allen, and this had been on the list.

Speaker I don’t know if, like, you can do this, but I mean, do you think there’s any way to couch their relationship as the adolescent within the Jacksonian, you know, hardscrabble, capitalist, materialist America that Jackson represented and that John Allen clearly wanted to be a part of and Poe’s adopted pose of?

Speaker Yeah, I mean, I guess what I would say lasts with Poe from his troubled and vexed relationship with John Allen is slavery, who grew up in a slave owning family in the South and was born to an actress in Boston, and he grew up in a slave owning family in the South. The family he married into owned slaves, the family he grew up with, own slaves, there are slaves and post stories all over the place. There is a, uh, an interest in. Cruelty and savagery info that is absent for many northern writers who write at the same time the Post writing, it’s not because he has a distaste for slavery. He buys and sells slaves. This is a part of his life, but it is because he has a proximate relationship to it. He has an intimacy with slavery that writers whose work we tend to read from the 19th century to, you know.

Speaker That’s not the answer you asked for, but I do think it’s an important point.

Speaker Yeah, I mean, can we talk more about the what?

Speaker So where do you see this other than the goldbug where there’s clearly a slave and PM where there are plenty of of not not slaves, black people.

Speaker Where else does it come up? How you see slavery in post stories or poems or.

Speaker I would have to think that through and haven’t I, I guess I.

Speaker See it in his criticism. So when Longfellow went to England in 1842, we went to the continent first and then he visited Dickens in 1842. And while he was there, Charles Sumner wrote to him and said, I really think you need to turn your pen to the cause of slavery. Charles Sumner became Massachusetts senator, a great abolitionist, most important abolitionist in the North Midwest. At a time when abolitionism was a radical political position to hold and Longfellow was not a man known for holding radical positions, but he was very temperate fellow, but he was much persuasive. Charles Summer was his very best friend. They were incredibly intimate. And he was much persuaded by Sumner that it was important to write about slavery. So on the ship home from London, where he had stayed with Dickens and he was carrying Dickens’s American notes, Dickens’s travel narrative in which Dickens had included a chapter Daming Slavery at Charles Sumners behest, Longfellow wrote a book of poems called Poems on Slavery that are actually quite interesting. They use all the conceits early 19th century abolitionism, their sentimental, but their stirring. And they were meant to be stirring. And they stirred so many people that Longfellow was asked repeatedly to run for Congress to become a politician, to take, you know, to become a political person, not just a poet.

Speaker Poet reviewed. Longfellow’s poems on slavery and just made fun of them, made fun of Longfellow as a Negro lover, and so there is a place where you see Poe’s animus toward New England writers, to northern writers, to people like Longfellow.

Speaker It’s that they’re wealthy, it’s that they’re successful. They have cultural authority. They’re from Harvard.

Speaker Longfellow was a distinguished professor at Harvard for many years.

Speaker But it’s also that they’re opposed to slavery. Most of those guys are abolitionists and Poe is not. Poe is very pro slavery. It’s he finds their moral piety about slavery, the moral poverty of abolitionists contemptible. It absolutely animates how he thinks about the literary rivalries that he gets involved in.

Speaker So you do see it. I think you you know, a keen reader could could come up with plausible readings of some of those stories. It’s impossible in the 19th century to write about anything without in some way or another reflecting slavery. I kind of think of them, but I haven’t I haven’t done that reading and I’m not prepared to. I do sometimes think of the man who is used up that story. Um. As having a lot to do with chattel slavery and the becoming of chattel, but I haven’t read it recently enough to give you, you know, to say something compellingly, something compelling about it.

Speaker Yeah, I’m trying to figure out how we can.

Speaker So he did I mean, growing up in China and south, of course, there were slaves and apparently the main slave market in Richmond was right near their house.

Speaker So people fretting about the fact that he would have walked by auctions all the time and that sort of thing. Did that make him?

Speaker How did he fit in? Not counting the Boston writers, the New England writers, just sort of American writers in general and magazine writers and the sort of popular press that he was he was writing. And did that make him unusual or were there other writers that were also as pro slavery as he was? Where did where did he fit in that, you know?

Speaker Um.

Speaker There weren’t a lot of writers of fiction who we still read.

Speaker Who were particularly opposed to abolitionism, the pro slavery argument doesn’t start until the late 1930s, 1840, just not until abolitionism, abolitionism gets very strong that people become pro slavery. So there are plenty of Southern writers who wouldn’t defend slavery, but it’s part of how they tell their stories and what they write about. But but the active defense of slavery is something that really doesn’t get.

Speaker That forceful until near the end of Poe’s life, Bo.

Speaker I do think, you know, politically.

Speaker Is an opportunist.

Speaker Above all, he doesn’t have political principles that he defends its he, I think, is fairly contemptuous of political strife. He tries to ingratiate himself to the Tylor administration of the Harrison administration to whoever is in power if he thinks there is a job and and money for. He’s a desperate, desperate man. He’s not in whatever he believes it is and believe about slavery. He’s not acting on his principles one way or the other. He’s not taking some brave stand in one way or the other. That’s not that’s not where he spent his energies or where he found his passions. I just mean to say that as a man who lived in that era, has anyone who lived in that time and place, he was affected by it and it suffuses his writing.

Speaker All right, you mentioned the Tylor thing, I did realize that you mentioned in the essay, too, when he went to Washington and eighteen forty three to try to catch up in the Taylor administration and ended up getting drunk.

Speaker And Rob Tyler, apparently Tyler’s son, wouldn’t let him in the White House or I don’t know if you remember it.

Speaker I don’t know very much. But he does drift from. Opportunity to opportunity, sabotaging each and every one.

Speaker But again, this isn’t distinguish him from most men on the making, the 18, this is what you would what you do. A lot of people trying to get political appointments in 1843. There’s not a lot of work.

Speaker It isn’t some terrible failing of polls that he was unsuccessful. Yes, he’s a drunk. A lot of people are drunks. This is why there’s a temperance movement. This is a huge problem with people drinking people out of work, drink.

Speaker Make policy seem ordinary, just defeats your project, but he’s not bad. Yeah, the idea that he’s, you know, so extraordinary is largely his idea.

Speaker OK, how are you doing? One or two more or what’s your one more? OK, I got to get all the way to Jennifer. Think of what is the most important one. We never talked about Gene Standard, his teenage crush.

Speaker If if you can’t talk about it just in the context of this sort of Byronic thing that, you know, he was was he trying on different persona here, different images, different identities, or was he just.

Speaker I don’t know. And that’s the adolescent pose. Very interesting. It feels to me like he’s just.

Speaker Well, you know, we interviewed Marilynne Robinson for this. She was great. She said something like, you know, for someone like Born in the North, orphaned, brought up in the south, but never really adopted by his foster family, he had to find some identity.

Speaker He had to find someone to be. And so he was constantly looking for these different characters. Yeah. Yeah. Including a poet being a poet. That was something some place he can belong. I mean, I’m not trying to, but it’s I’m just saying that’s like I’m just wondering if you have any observations about that and how it fits into the Jane Stanard thing.

Speaker Yeah. Yeah. Well, I think that Poe was rather extraordinarily influenced by. The interest in American culture in the 1920s when he was a teenager and solitude and loneliness and the life of the hermit and also the kind of. Spooky new graveyard culture. So, again, like we think of these things like Sopo and 1823 falls in love with, you know, the unhinged mother of a friend, Jane Stannard, and she dies the next year in an insane asylum and Poe grieves her. But that and, you know, I guess the story goes you spend endless hours at her graveside and that this is this is part of the schtick about Poe, which is I think you need to know about Poe. You picture him like looks like Johnny Depp and Edward Scissorhands.

Speaker And he’s like, oh, James, you are no more.

Speaker And no the drama and the adolescent melancholy of it. And again, like that, that that that is Poe.

Speaker And that is a piece of who he is. And his kind of particular loneliness as a biographer you could point to is. Particular neediness as a as a young man, as a motherless young man and the child of a beautiful woman who died when he was very young. You know, a trauma there in a minute and a distress that he keeps reliving again and again and again. That said, you know, this is the time when the kind of key figure in American cultural life is the German people are obsessed with hermits like these people who live like they’re always finding hermits who live in caves and who’ve, you know, forsworn society.

Speaker And, you know, people read these long poems just as chief justice who really becomes Justice.

Speaker Joseph story. The Supreme Court justice writes this one poem as a teenager called The Power of Solitude.

Speaker And it just goes on and on and on. And it’s just like seriously, like he grew up already. It’s, you know, whatever. So it’s lonely. Yes. You’re 14 and you don’t have somebody yet. It’s lonely. We get it, you know.

Speaker But the loneliness and the hermitage thing and the early American republic is actually about democracy. It is about the need to be part of society. There is no opting out. You actually need to participate politically. This is an all in political culture and that you’re here that all the time. All the time. All the time. All the time. You are a citizen of the republic. You must belong to the Republic. You must stand and be a virtuous citizen of the Republic. And against that you have this kind of ironic romanticism. And, you know, Wordsworth wrote a poem about the recluse. And so this is all the romanticism coming from across the ocean.

Speaker And kind of it smacks up against this American. You are a citizen of the republic, and then you have these kind of swooning queens, you know, and I’m a citizen of the republic. But but I just I need to be alone, you know? But you must belong. But I need to be alone.

Speaker And this is all you can sort of see that manifest in in in a lot of people. But it becomes becomes a kind of arrested development problem for honestly, like you just like I can get over that. Like, you need to alienate yourself from people so that you can be alone, so that you can alienate yourself from people, so that you can be alone, so that you can easily, like, stop just move on to form meaningful attachments to other grown ups. That’s what he does. Never does. He never does. He never just doesn’t do that now again like that. And then he convinces himself that this is because of the beauty and brilliance of his soul in his mind.

Speaker You know, some people, some people by that, I, I, I find that to be silly and I find it is often very sad.

Speaker It’s a sad thing and po po po po is very smart.

Speaker And he also gets that that’s not what he really he also gets that there’s a damage there rather than a genius or that there can be both he wants because the whole culture wants to think of genius’s damage and damage is genius. And these things are all one post clever enough to know there’s something actually wrong with him.