Speaker The canvas lives out on the island, and he said he said he makes these pills, man, every kid.

Speaker Uh, probably. We’re going, yeah.

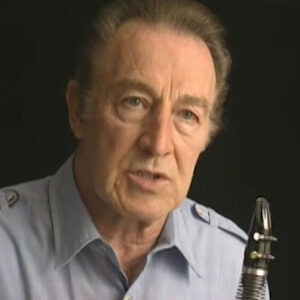

Speaker Well, my name is Jim Maxwell, and I’m the trumpet player who did not replace Harry James. I followed Harry James because he such a spectacular trumpet player. I don’t think anybody would replace him. But I joined Benny’s band in 1939. And I think my main claim to fame now is that I’m one of the few survivors from that time. And I had always been interested in jazz along with wanting to be a priest.

Speaker And excuse me, just do look at me.

Speaker If you can’t say, oh, shall I start again from all over.

Speaker Yes. And take don’t don’t feel you have to rush when you talk about something of being a priest and then how that changed that you didn’t get to that last.

Speaker No, I didn’t. Well, here we go. My name is Jim Maxwell and trumpet players Benny Goodman. I joined in 1939, replacing or rather I should say following Harry James, because no one could replace such a wonderful trumpet player as he was. And this followed from a long interest in jazz. When I was in the seventh and eighth grade, my interest were music and wanting to be a priest, which at the time didn’t wasn’t a particular conflict because I never dreamed that I would be playing in bands. And I used to listen to Louis Armstrong in the late 20s from Sebastian Cotton Club in Culver City. I’m from California myself. So we heard it every night. And he was so thrilling that I think that was my first interest in jazz. And shortly after that, my my father, who used to listen to a program in the morning called Captain DOBs, his ship of Joy, which was one of those uplifting programs. It was Canary Canary’s Twittering and old ladies writing in how much better they felt. And I would try to get out of the house as soon as possible. But this one particular morning, he had the program on and all of a sudden I heard this spectacular, spectacular burst of sound. And I asked him, what? What is that? And he said, I don’t know what it is. Some I’ll say a colored band. And my father used a different word and. I sat down and listened to the whole thing. I couldn’t believe it and my father working on the railroad, he was able to give me a pass to for the trains. And the next day I went to San Francisco and to the theater where Duke was playing. And I sat for the first two shows and then went backstage to meet the people in the band. And I met Cootie Williams and Freddie Jenkins and I thought, well, of the first trumpet player, the three trumpet players from the band, and Ivy Anderson, for whom I formed a lifelong crush, even culminating in a proposal in the early 40s and. I sat there and talked to them and about music, and I’d love to play in a band like that and ask me what I played, but at the time I played bassoon because my cornet that I had had broken and the school had no other instruments but bassoon. So I played that cool. He kind of laughed and said, well, he said, you know, we’re not going to have it. It’s not likely we’ll ever use a bassoon in this band. So he said, you better go back to trumpet.

Speaker So when I went back, one of the local barbers had bought a trumpet from out of work man for five dollars, and he let me have it for five dollars. This was during the Depression and so on.

Speaker I know I used the word until some black musicians freaked me out. OK.

Speaker I’ll start at the beginning with, uh, with you.

Speaker All right, uh, my other favorite in music was the Duke Ellington Band, and I first heard them, I guess, when I was in the second year of high school. And my father used to listen to a program every morning called Captain DOBs Ship of Joy. It was an uplift program with Canary’s Twittering in the background. And he would read letters that old ladies would write to him and say how he’d uplifted them and changed their lives. And I finally got a great kick out of that. He was very romantic. And, uh, I was trying to get out of the house as quick as I could because I couldn’t buy the program. And all of a sudden I heard this burst of sound like I’d never heard in my life. And I stopped. I said, what the hell is that? And he said, And I don’t know who it is. And so I stopped and I was listening. And it turned out to be Duke Ellington. And they mentioned they’re playing in the Fox Theater in San Francisco. So my father worked for the railroad and I was able to get a pass through him for the next day to go to San Francisco. And I scrounged up a couple of dollars someplace or other and went to San Francisco. And I spent the day in the theater. After two days to the first two stage shows, I went out and went backstage and I managed to get down and meet the band. I met the three trumpet players, Arthur Whetsel, the first trumpet player, and Cootie Williams, one of the jazz trumpet players, and Freddie Jenkins, the other jazz player.

Speaker And the second. It’s shot and talk to the media, Cootie Williams, maybe Judy and I, because I know when I went backstage to meet the band, I met Cootie Williams, who was a wonderful plunger player, and Ivy Anderson, who was a singer with a band.

Speaker And I formed a lifelong crush on Ivy Anderson at that time, which ended in a proposal in the early 40s, late night, late 30s, I should say. I got married in the early 40s or at my wife naturally to my wife.

Speaker You’d better go back and I up before you and and keep going with it.

Speaker Do so. We were talking and they asked me what I played and I said I was playing bassoon that I used to play clarinet, but my quintet had broken and I couldn’t afford another one or even to get it repaired. And the school had a bassoon for offer. So I learned to play bassoon. I taught myself from a wall chart I had and he laughed and he said, Well, I said, they don’t use bassoons in the jazz bands right now. And I think you’d better go back to the trumpet. And so when I got back, my father had a friend who was a barber who had recently bought a trumpet for five dollars from somebody out of work.

Speaker Man, it was still the Depression and there were a lot of unemployed coming through the town all the time. And I started practicing again.

Speaker And that same summer I went up to visit my grandparents in Washington and some of their neighbors were young fellows who played in a jazz band. And they invited me to come out here, hear some light, said bring your trumpet, you can sit in. And so I did. And I said, I don’t know what to do. And I said, well, you know this song? And I said, yes, I played the song. And I said, no, jazz it up. And I said, I don’t know what you mean, play jazz it up. Said, Well, you know, improvise. Do you ever hear of Louis Armstrong? And I said, Oh yes, I heard him a lot. I still try to play like him. So I tried to play like him and which I’ve also been continue to do for the last 60 years, as a matter of fact. And that’s how I got started to play jazz. And when I went back, I would listen to all the records I could and copy the pieces and the soloists. And of course, one of my great favorites was a Charleston Chases, Benny Goodman and Jack Teagarden. And and so sometimes Marty Klein.

Speaker And later, I think Benny Barrigan and.

Speaker Also, I heard a good deal on some of.

Speaker It’s Billie Holiday, thank you. What’s the matter with that?

Speaker I heard Benny Goodman playing on the early Billie Holiday records with Teddy Wilson and Lester Young and Buck Clayton sometimes. And. So I was very familiar with his playing about 1932, I joined a band in Stockton which was run by Gil Evans, and at that time the band copied the Casanova band and he would buy the records and he’d copy the arrangements are faithfully the ballots were beautiful because it was the first band, I think, where the musicians doubled on other instruments. Read players particularly would play flutes and odd instruments like E Flat looked like a bass clarinet and bassoon. And even in the brass section, Sonny Dunham doubled on trombone as well as a trumpet player. I don’t know which was a double. He played them both and it was all right. You know, the ballots were beautiful. The jazz tunes were doubtful. And I copied some records myself, some of Duke’s arrangements and a couple of Lunsford arrangements. But then the Benny Goodman program came on on Saturday Night Dance session. It was called Saturday Night Dance Session. And they had three bands on their Benny’s band for jazz. And I think it was Kogod for Latin Music and. I can’t recall what we call society music, music he could dance to, and that was really an eye opener. It was a thrilling thing to hear. And we heard Bunny Berrigan really play for the first time. And so the girls started copying Venis records. I remember the first recopied was King Porter Stomp and sometimes I’m Happy, which was on the other side. And I copied the solos on those. And I generally didn’t play other people’s solos, but those were so good that it was pointless to try to play your own. In fact, when I joined Benny’s band, I still played those solos and I, I guess a little bit I tried it tended to play. One night I played Barney Solo and sometimes I’m happy and I think Benny might not like that. And the next time I played my own solo on it, he came to me in the animation. I said, Why don’t you play money? So perhaps I said, I thought you wouldn’t like it. I don’t know. He says, I like it when you play the solo on the record, he says. People like to hear the same solos when they buy their records and they hear the band. So I said, looking for her too. And he said, Oh yeah, I played Bunny Solo on King Porter, if you can. I said, I can play it. And so I started doing that and I had about four of his that he Bunny had recorded with Benny. And, you know, so going back then to Gil’s, Gilsenan recopied Venis arrangements and the summer of 35 in California and Benis Band was on its way out was to the Palomar and they stopped off in Oakland and Suites Ballroom to play. And so we took off that night, the whole band, and got into one band car. We had 12 of us and drove up to Oakland and got into the ballroom early so we could stand in front of the band. And I saw Bunny go out to the men’s room and I followed him thinking, you know, just look at the man. And he went in the Benz in the men’s room and reached in and pulled out, I think it was a half pint and uncaptured and lifted it up and gurgle gurgle right down. I thought, aha, that’s the secret of playing jazz. I had already had one secret from reading an article in Fortune magazine about Louis Armstrong and a record of his called Mughals. And this is had a note under that saying Mughals was a marijuana cigarette, which it is rumored that Louis Armstrong was his inspiration to, which is what I had tried that. But that was a disaster because when I whenever the few times I tried it, I would forget whether it even played the solo. But when I saw that one he was drinking, I thought, well, that must be the answer. So I was a footnote to that. I tried it briefly and it doesn’t work out too well.

Speaker So did you talk to him then or talking?

Speaker Yes, I talked to him a little bit and he said that they were going down to the Palomar and and then the band and the trip is going to fold up because it had been a disaster. They had played in Elitch’s garden in Denver.

Speaker I think there was. And and there was practically nobody there.

Speaker And, uh, so then he was very depressed and unhappy about it. But I guess it’s jazz history that when he went down to the Palomar, which was a huge ballroom, took up an entire city block. It was amazingly big. And he would pack a ballroom every night.

Speaker And I think and I think some people who know those things also thought that the reason he made a hit there was there is a dance they called the Balgowlah from Balboa Beach, where the people seem to stand in one place, but the feet kept moving and other parts of the body. Sometimes you would think that maybe they should have been married before they did the dance, but it worked out well for jazz music. It was not like the lendee, which was very active and gymnastic that it was didn’t make up any room, as they say, to just the lower body kept moving and the upper body was stable. It’s all that changes, they say, change the history as far as jazz is concerned, because many from that time on was more cheerful and went on to be more famous.

Speaker Did you go down to hear him at the Palomar? Oh, yes.

Speaker Describe what it was like walking in the room and hear this guy being like nobody a week before.

Speaker Well, I don’t think I even thought of that. I just thought what a thrill it was to hear this wonderful sound in person. And and we’d go up and force our way up into the front of the band and just stand there gaping all night. And everybody played good. And Bunny was in that band. And I went backstage and talked to him again. And I told him I played Valpo of each and that I love to play jazz and how much I liked him and Louis. And he said, well, you can’t go wrong. And Louis said, I don’t know about me or something modest. And I said, yes. I said, I love to play jazz. I said, but I don’t pay much attention to the parts. And I’m a second trumpet player in those days. The first trumpet player Gener almost never played jazz. The second trumpet player was a jazz player and the third player generally was an alcoholic friend of the wife of the leader or a cousin of the leader or somebody in the band. And that was not the case. And Benny’s band, as it happened, he late Kasmir, who was a very good jazz player himself and a very sober trumpet player, and I had some cases relatives here that show that. But that band was was different from the small time bands that I had known up until then. And I told everybody about I’d rather play the jazz in other parts. And he jumped all over me and said, if you want to be a good musician, he said, you learn to play the part. You said you listen to the first trumpet player and you try to anticipate what he’s going to do and play exactly as he does. And I carried on about that and. It’s a very chastened I went out and that from that time on, I avoided him until many years later when I met him in New York and.

Speaker So, uh, should we skip to to your next encounter, I mean, if I let you know now that you want to talk about it, I know the money then came back to the Palomar a few years later, and you got to know him better when he came down to hear you. Oh, yes, that’s right.

Speaker We go in Tator.

Speaker All the big bands that used to come to the Palomar would come down here, Gil Spann, because apparently we got an international reputation with jazz musicians and Benny would come down and Jimmy Dorsey’s band would come down and cancel. My band would come down to hear our band. They couldn’t believe a kid band could sound like us. And Benny liked the band so much that he got us a contract with Victor Records and found something we never did because Gil never felt the band was good enough. Gil was very modest and we used to drive us crazy and we’d go talk to the manager and the Music Corporation. He’d say, What do you think? You’re ready? And you don’t say, Well, I don’t know. And we say, yeah, we’re ready or raring to go. But so we never made these records and.

Speaker There was once one time when he was there and Gill asked him if he’d ever heard Lionel Hampton and he said no, but he had heard about him. And so we arranged to meet him and John Hammond in Los Angeles. And Gil and Vito Mousseau was a tenor sax player. And I met them and we went to this restaurant in Los Angeles where Lionel was playing and Benny was sitting there is just enthralled. In fact, he had his clarinet and he went up and played with the band. And Vito went up and I went up and played with them, too. And he was sort of impressed by everything that he hired Lionel to join the band and be the I guess that was the start of the trio. I don’t know what it quartet because he already had used Teddy, I believe, and as part of the trio. And he also hired Vito Musso. And he also but he neglected the trumpet player myself, which didn’t make me feel so good, but that’s the way it was. And and so we feel that we had something to do with the history of that starting that combination.

Speaker Can you can you describe that night? You remember what it was like sort of piling in the car and driving down and describe the place? He said it was called the Chicken Shack.

Speaker Yeah, I think it was called the Chicken Shack. And it was a small band with a little six or eight piece band. And there used to be a lot of these little black bands all over the country wherever you go.

Speaker And you could sit in with him if you were a musician and they would copy the arrangements of the big bands and were really good bands, really good musicians. But they had one problem, and that was they were black. And so they only could play for, you know, black clubs or or but certainly never in any of the big white bands. And they they serve fried chicken and French fried potatoes and things of that kind. Some of them would sell ribs and still smelled greasy and full of tobacco smoke and stale beer. But they were exciting places to people from a small town, as we were. And it was a very exciting night. And I got to be sitting at the table with a giant clarinet player, you know, Benny Goodman, and then to actually go up on the stage and play with him, even though he didn’t hire me at a child, I got over the hurt of that very quickly and I was studying was Herbert Clark at that time, a famous quintet solo from Sousa Band. And so I thought, well, I’ll continue my lessons. And Jimmy Dorsey used to come down a lot to listen to us and take me out afterwards and go up to the Central Avenue, which was sort of the Harlem of Los Angeles. And there were a lot of after our clubs, they have little bands or bigger bands. But Clayton had a big band. There used to be Earl Mancillas Band and gone to the Orient and went broke and the band came back steerage somehow or other and locked up the band over and we’d go up and you could sit in there. But there was a club called the club. Alabam was in one of the hotels and it went up until about eight in the morning. It was an illegal club and, uh, but all the jazz musicians would go there when he was in town, Teddy Wilson would come there and, uh, and Fats Waller. And I remember one night seeing Art Tatum, Fats Waller, Teddy Wilson, just Stacey all got up and played. And then Art Tatum got up after each after the three years and had played off. And he had remembered their solos. He played their solos better, then embellished on the solo, each one of them. And they’re sitting there laughing. And they were insulted because the gap between Art Tatum and other pianists was so great that I don’t think anybody had any envy of him or jealousy. Maybe they had envy, but certainly not jealousy. And so I used to go there a lot was with Jimmy Dorsey and we’d play and so forth. Then Gil got around to firing me one time. Well, the only time and that’s presumably because the wives in the band complained, I set a bad example for the husbands. I was going around having a good time drinking and carrying on with girls and going out and playing every night, and they couldn’t do it. So that’s why I was being fired. But I like to think it was really because I thought I Jimmy Dorsey wanted me to go with his band and that I was too loyal to do it. I would have been, but it wasn’t true. He had asked me to join him. So anyhow, I was fired. And over the time I played different clubs around L.A., it was Maxine Sullivan in a place called the Trocadero, which was. Big favorite, the film stars. Well, those awful bands with two trumpets and Harmon mute three tenors and three fiddles, you know, and and all the famous movie people came there and I got fired from there because I used to have a Bebe Peashooter on my trumpet and, you know, pop people. I was the one you see wiggling around and couldn’t resist it. And so then I went to work with Maxine Sullivan and was there until she closed. And then I went back with Skinny’s van skinniness, which had taken over Gil Evans band. And we would go up the coast every summer and the summer we’d gone up the coast. Benny Goodman band replaced us as the restaurants that we played in and Beverly Hills. And when I came back was there last night and I ran into John Hammond there and I said I heard something in the red in Downbeat that Miss Misere was about to start a mixed band in New York. And that I would really like to get to New York and play in the band. But I didn’t have the money to get there or the nerve to get there. And would he speak to Miss Role when he got back and see if he could fix me up? And he said he didn’t remember my playing too well and could we get together, but we never seem to get together. So he hear me play in a club. So he told me to come around the next day to NBC studios when he was rehearsing, and I could sit in with a band and he let me play some solos and no matter what I played like so I did and played one o’clock, jump and roll them in a few the standards and went, OK. It wasn’t I didn’t feel exactly jazz history, but it was good enough to get with Israel and I think John and everybody and walked out sitting on the bus stop waiting for a bus. And I heard Benny talking to the manager and he said, hey, that’s a kid. You said in the band. And I was 21, I think at the time he saw me as a kid. And Leonard says, yes, Leonard was a manager. And Benny came over and he says, What’s the matter, kid? Don’t you want a job? And I said, What job? And he said, the job. And my band. I sure I didn’t know I was auditioning. He says, Yeah. What did you think you were doing? I said, Well, John asked me to come around and sit and play in the band, and I was sort of fishing around. I didn’t want to ruin my chances, so I really didn’t know what I was doing. And you didn’t say anything. So I left. Yeah, I said you got a job if you wanted. You should be out at the airport tomorrow morning at 10:00. And we’re going back to New York. And I said, my God.

Speaker And.

Speaker So you can jump in now about Harry James, in case we missed it in the introduction that you were taking Harry James place.

Speaker Yes, but well, by a few months, somebody else had taken Harry James place and he was a good trumpet player, but he had what they call a piccolo trumpet. It’s an octave higher than a regular trumpet. And he used to play his solos on this piccolo trumpeters. And then he didn’t like people playing up in the clarinet register, which is why he would never hire Roy Eldridge. I was always getting trying to get him to hire Roy after Cootie left. And and he said, no. I said I do all the high loud flying. So I’m sure he didn’t like the fellow with the piccolo trumpet. I can’t remember. His name is just quirky.

Speaker Something in the Catholic Church. Cornelius.

Speaker Yeah, I know that. I didn’t want to say his name. Well, yes, I had never played first trumpet in my life, as I explained earlier, that I was a jazz player. So I played second. And so I said, oh yes. And I’m feeling a little guilty about lying. I thought I meant to say that I didn’t play ballads or songs that was not too good at just playing songs, but it came out I don’t play waltzes.

Speaker And then he sort of said, well, this is, you know, perhaps he said, we don’t play waltzes. My band is left. And he had a funny kind of a laugh and wiggle his eyebrows. And so I felt I had done my little honest bit and I would meet him the next day at the airport.

Speaker There was some trouble with him.

Speaker Is that Margaret, can you talk to the guys in the back here about the noise?

Speaker Yeah.

Speaker So, yeah, I was sitting waiting for a bus and I heard his voice behind me talking to the manager, Leonard Patterson, and he said that the kid that just tried out for the band, I just was playing in the band and a lot of the jazz and Betty came over, says, What’s the matter, kid? He said, You want the job? I said, Well, I didn’t know I was auditioning. I thought I was playing for John, who was going to get me a job in New York. He says, no, he’s auditioning for my band. I tried to cover up and act like I knew it was really for his bands.

Speaker I blew the chances. I was really thrilled that he’s offering me a job. So he said, well, we’re leaving for New York in a couple of days and you can tie things up and meet us out at the airport. So the next day I went to the Victor Hugo to rehearsal they’re having and they had just hired Charlie Christian and he was rehearsing with Lionel Hampton and abandoned. Charlie was always fooling around. And Lionel, if he if he was standing still, he had his sticks in his hands or he was sitting in the piano playing third finger piano all over, you know, the same as he played xylophone, he just never stopped playing. And Charlie Christian was playing this thing. De de de de de de de de de la da da da dee da in L.A.. So, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. And he started de de de de de de de de de de de de de de de. And Benny picked up the clarinet and started playing doo doo doo. And the first thing you know, they had worked up an arrangement on it.

Speaker And and so then he said, well, this is as good. He said, what do you think? We had to call this piece? And Lionel Hampton said, well, we’re going home. Why don’t we call it flying home? But it’s okay, let’s call it Fly at home. That later became Lionel Hampton’s theme song, and I think he gets credit for having written it. But actually, Charlie Christian had did that riff in the first place unless they had been doing it sometime before I got there. But I don’t think so. Charlie was very creative and a lot of those sextet things, you really couldn’t pin it down to any one person. They just interacted and evolved one thing in another. I was always a big of big band jazz fan, and I tell you the truth, I like the sextet solos, but I never liked those tunes very much. I thought they were kind of corny, to tell you the truth. But then he really got into your head.

Speaker And we have Charlie and Lionel, as far as I know, it’s good of the next thing would be to meet him at the airport.

Speaker All right, so after the rehearsal, they’re packing up and everything. The manager came over and told me what time the plane was leaving the next day and.

Speaker There was a long discussion about my getting on the plane, and it seemed that I couldn’t take the same plane as a band because they had a charter plane and all the seats were filled there and there was one empty seat. But that was a seat that Gladys Hampton used to carry a fur coat on. And so I couldn’t have it and she wouldn’t hang him up or whatever the baggage. So I had to take a separate plane, which was interesting enough because the band played in Denver on the way back, because Benny always was he he always managed to put a stop in on any long trip. And I guess it paid for the trip. And I took a separate plane on American Airlines, which went the southern route, and I stopped in Dallas. It was very exciting. Newspaper reporters were in the airport and I had to come out and be photographed as a man who was replacing Harry James. And I don’t think people realize just a side thing about the popularity of the band and what it was like. If anybody remembers the Beatles era, it was like that. But I think. Maybe more so, because literally wherever we went at the airport or the train station, the literally hundreds of people, generally thousand or so would be a huge crowd. As you know, you could see a crowd maybe as much as a block stretch out of block. When we went in the Paramount, they were lined up the night before all the way around the block, and they slept on the sidewalk so they could get in to hear their show the next day. So it wasn’t strange that that the airport, when the airplane stopped it, there were newspaper reporters came to take my picture. And this was a sleeper plane, which is I don’t know if they don’t have those anymore. And it’s just like the Pullman births at nighttime. They they had an upper and lower and I had an upper because I was late and getting on the plane. But the stewardess, I said something to her about how big I was and everything was getting in the upper berth. And she talked the guy in the lower berth to taking another upper berth someplace. And so I had the whole section to myself in return for which I had to take her back into the baggage room and play some songs for a smoke gets in you two or three songs.

Speaker It was the price of it and.

Speaker Oh, before we left the manager, the bad decision, if you got any money and I said, oh yes, it’s how much you gonna save two dollars. He said, Well how are you going to get to Atlantic City? And I said, I’ll take the subway. He said, no, you have to take the train. And I said, Wasn’t that right next to Coney Island? When you get there on the subway? And he said, no, it’s a little farther. So he gave me 100 hundred dollars. And on the way there, I don’t know, I thought, I’m traveling in style now and, you know, name brand, you know. So I checked my baggage and my trumpet, which was a big mistake because I got to Atlantic City and I got my bags, but I didn’t get my trumpet, so I had to get there for the afternoon session and no trumpet. And fortunately, Ziggy had an extra trumpet, which he let me play, but his equipment was so different from mine and it was a different board that is the size of the hole and the trumpet. It was it was smaller than the one I used. And the mouthpiece was not as deep as the one I used so that it felt funny on my mouth with trumpet players listening person is not a trumpet player. A fraction of a millimeter or thousandth of an inch will make a difference to a trumpet player if the mouthpiece is not the same. Just even a little little big difference and it’s difficult to play. So I played first trumpet for the first time in my life, was the biggest band in the country with the trumpet that was totally and mafiosos, totally unfamiliar to me. And of course it wasn’t easy and it’s occasionally sounded like it. The meaning. I missed quite a few notes and one of the other trumpet player said something to me about this kid. You know, you’re the big time now. We don’t miss notes in this band and always does. Ziggy Ellman’s credit. He leaned over and said, You son of a censored, you missed more notes in one night and the kid missed all week tissue paper. He called him tissue paper clip. You missed more notes in one night. So that squelched him. And it was a you want a lifetime lifetime friend and admirer. He was a wonderful trumpet player.

Speaker He all the more my. Yeah, I’m sorry.

Speaker So he won a lifetime, Fred Ziegel, and we won a lifetime, Fred and me and admirer, although I didn’t originally admire his jazz, it didn’t sound like jazz to me.

Speaker And but he was such a great trumpet player that I did admire it. And he had some of the first parts. And when he would play first, I would follow. It was like being rushed along by a big river. He was such a powerful first player and had such a drive in his playing that it was a lesson to me.

Speaker You some you told me the day that at first it was that you didn’t have a lot of buddies in the band, but to put it mildly.

Speaker Well, when I got when I left, the band of the manager of the band was a man named.

Speaker Oh, hell, I’ll start again, please.

Speaker Yeah.

Speaker What was his name, that adventurous? Thank you. The manager of the band was a man named Leonard Vanness and he was engaged to the former singer in the band, Martha Tilton. And I had known Martha and her sister Elizabeth, who sang with Gil’s band and the whole family, in fact. And I had taken all of them out, including the mothers on a few occasions that were good friends. And and on hard times, I would eat there occasionally. And they took an interest in me, worried about my being too thin, which is hard to believe. And I sit here 285. At the time I was 185. And so they felt that I was really sensitive and this band was kind of rough and tumble. And she told Leonard, he said, you ought to look out for Jimmy. You know what? He gets to New York and sort of look after him because he’s very sensitive. And that’s not quite the right thing to say, considering the fact that in Beverly Hills at that time, there was a large homosexual population and we all mingled freely and we’d even sort of kid around and camp a little bit to them, you know, as a sort of big joke. And I played on the Bob Hope show and he was always camping.

Speaker It was sort of a good humor joke. We weren’t politically correct, but we didn’t hurt anyone’s feelings either. And when I got to New York, I continued to do that and. So with that plus the fact that I was a sensitive person, plus the fact that I used to take his wife to be out for which she probably didn’t like that idea too much, he sort of spread the rumor that I was gay and I didn’t know it, but I knew something was wrong. Nobody had much to do with me except the black guys. And they’re very black people, by and large, make a generality, are very tolerant of all people. They don’t discriminate.

Speaker And if that if they believed that it didn’t bother them. Lionello had known me from before anyhow, so he knew better.

Speaker And so Fletcher Henderson was a good friend of mine. Fletcher was very much a gentleman, Polish man.

Speaker And I think I told you the other day, he reminded me of Warren Williams in the movies when it was New York, New York movies where you get out of the taxicab and they’d show a shot of the big skyscraper and he’d walk in with his homburg and his long, you know, coat.

Speaker I can’t think any of those four and walk into the building and the striped trousers and the deal.

Speaker And Fletcher was a type of person. He was very suave, very polished. His hair was looked down and his face was always very calm mask. I thought probably underneath he was seething, but you would never know it and.

Speaker And he was very nice to me and Lionello was nice to me and Charlie, but Charlie was always kind of out of it. He was in his own world all the time, and he’s singing all the time on the bus. He used to sing Shimizu Wobble all the time. And we rode together because I joined the band at the same time he did. And he sat there poppin his fingers, singing. She would shimmy, she will she flew around the room, she throws it on the ceiling, she throws it on the floor, she throws it out the window and she catch it for a fall. Shimmy choo wobblers go on for eight hours. I don’t think the words are any place close to right, but that’s what he said. So I thought there was another scene floated on the floor. Throw it out the window and catch it before it falls. And he told me the story about we’d talk occasionally and talk about how he always wanted to be a tenor sax player because he loved Lester Young and you could tell in his playing he was playing, he played lines like Lester Young did. But of course, he was very poor family. And his uncle had a guitar, which he gave him, and he played Lester Young solos on the guitar. And he’d made an amplifier for himself out of an old kind of a hard, hard case suitcase with just a little speaker in it, a tenured speaker and a part of a radio. And I think in those days you could get a little cheaper electric phonograph, ten dollars, and you could connect it to your radio by sticking it under the cap of one of the tubes and putting the ground connected to the chassis and play through it. And that’s what he did with his guitar. And actually he used that same equipment to the band and he had this homemade said he never bought a good sweater. Well, I don’t think there was such a good thing as a guitar amplifier because he was the first well known, amplified guitar player. There was a man in the village called Leonard, where he was an awfully good jazz player on four string guitar, and he had an amplifier. But I don’t know any other guitar player because any lying and Congress at all, the earlier guitar players, they they all used acoustic guitars were amplified.

Speaker And until until after Charlie Christian and the guitar players amplified in a bit of a maintenance in that he was really the first electrified.

Speaker Yeah. Yeah. Well, it’s also very dry conditions, you know. Let me just I just heard that I never noticed.

Speaker Remember, he was oh, Charlie, we’re talking about wanting to be left to start again already, Charlie used to talk to me a lot about how he wanted to be a tenor sax player, but being poor, he could never afford to buy a saxophone. The only instrument he could get was an acoustic guitar of his uncle’s, which he played and tried to play like Lester Young. And I would say successfully because he played the lines very similar to last year. And he had this homemade amplifier of his, which was some kind of a hard covered suitcase. He cut a circle in and put a native speaker. And I think what was a chief, a little radio.

Speaker And in those days, you could buy a very cheap phonograph for ten dollars from Victor, put it out around on psychology, give me a little push and it would keep going. And so you stick one wire under the header after a dying tube cap and then the other wire would go to the ground and it would be an amplifier.

Speaker I could play records through it on his case. He played his guitar through it. And as I think back on it, I believe he used that same equipment all through his career. He never bought a professional set. But it occurs to me that there was no such thing at that time. As a professional said, I think he’s the one that started the business of the electrified guitar.

Speaker Certainly people like Van Epps and George, different people, the famous guitar players never used the electrified.

Speaker They played acoustic with the exception of a man named Leonard, where he used to play down here in the village on a four string guitar. And I think he had the same sort of set up and made his own metal amplifier.

Speaker And undoubtedly after Charlie Christian, everybody started to get electrified. Until now, you rarely hear anyone playing acoustic unless they’re classic classical guitarists.

Speaker And I do need some other stuff with you on the bus. Do you think the youngest.

Speaker Yes, he would sing Lester solos sometimes I wish there was one called Twinkletoes, which which I know.

Speaker Dee da da da da da da da da da da dee da dee da. You like that?

Speaker He would sing it a lot and we sometimes we’d have it together and uh.

Speaker And but, uh.

Speaker I’m just while we’re on track, we should talk about in the I think in the book you talk several people do about when he got sick and the troubles that some of us got a little help from his friends.

Speaker We’re trying to help them out really fast.

Speaker Yeah, well, Charlie, you know, he was a good time livery.

Speaker And he like anybody else, he was in big money and he liked to spend it to have a good time and a drink and maybe smoke a little or like all the time. And he liked the ladies, too. And the process of it got a few ailments. And then because I don’t know whether his background as poverty is, is his energy, his strength was not that good. He got tuberculosis. And if and when we were in California, before we realized that’s what he had been, he would send a limousine every night out to the hotel to get him and bring him to work and take him back. But by the time we got to New York and he got to a bed, he sent him to a doctor that he know he was found to have tuberculosis and was sent out on the island to a hospital out on the island. I can’t think of the name of it, but it was a state hospital, which means you probably wouldn’t come out of it alive in those days, particularly if you were black. You don’t have much of a chance. And he didn’t have too much help to come out alive because he had a couple of good friends in the band who would go out and see him every week or two with with a jar full of pot, maybe a couple of bottles, and one of the 40 second street hostesses and all all the things that he shouldn’t or shouldn’t be doing.

Speaker And of course, he died. And I don’t know if if he. Could have lived, but certainly those things didn’t do him any good.

Speaker And.

Speaker Then take him out of the car, you know, for a day in the country.

Speaker And you got anything but fresh air and.

Speaker I don’t think he ate too well either, because when we be on the road, it was difficult with diners, particularly when you get into Ohio and some of those states, what would generally happen is some of the white guys, the bad would go in and bring out the.

Speaker A little bit. OK, this. OK, um.

Speaker I go back to the hospital. Charlie was out in one of the state hospitals out in Long Island and by that time he certainly was full blown tubercular and he had a few social diseases, I believe, and and he had visits from good friends who really may have thought of giving him a good time, but didn’t have his interests at heart because they would bring whiskey out to him in a cup and a little kind of pot or something.

Speaker And they one of the hostesses from 40 Second Street and give him a day in the country where I guess he got anything but fresh air. And I don’t think that he ate too well and is probably being poor boy, he didn’t eat well and his whole life. And what I do remember that he could eat pretty well in New York when we were in the Waldorf after work, we used to meet her to pick her up and the different bands would meet there. And generally Charlie and I would go there and Bass and Lionel would go there, but he could get in on the eating club bass. He was there. Coleman Hawkins was a big eater, and I had become good friends of Mildred Bailey. And she would be there. And the idea was whoever ate the most didn’t have to pay. And so everybody would have a couple of order of ribs and maybe a barbecued chicken and and once or twice I kept it off with the order of barbecued shrimp so I wouldn’t have to pay. But that was our eating club. There was also a place uptown called Mrs. Fraziers Chicken Shack where all the musicians like to go. And they had a great jukebox because they had nothing but jazz bands, records, black bands and Coleman Hawkins Records, Roy Eldridge and Basie and Duke. And she was a wonderful cook. She had just simple dish like pork chops and grits with gravy that it was just wonderful that you couldn’t cook it yourself at home much and a lot of the good eaters would go there to Ben Webster. Was it a good idea to spend?

Speaker We go in a number of directions, so it’s, uh, maybe we should talk next about. Getting booty in the band, is that skipping ahead too far?

Speaker We want to talk first about, uh, yeah, up the tab.

Speaker Well, when I first joined the band, I don’t know why, but I had to hang around Benny’s dressing room all the time. I don’t know where I got the nerve, but I was so thrilled about the whole thing. And as I said, nobody else talked to me very much. And so I would go in there and talk to him because I didn’t drink either and generally ended intermissions. Everybody would have a bottle and we’re drinking it. And I just felt sort of out of it and. In addition, venue was awfully nice to me in the mornings, I would go to the job if we’re playing a theater and take a cab together and go back to the hotel when the day was over and take a cab together, and sometimes you would go out and eat together. And after about a week of this, Legalman said to me once you said you and Pop seem to be getting along. Benny called Everybody Pops. So we called many pops. And he said, yeah, he’s really nice to me. And you see, hey, you got a real honeybun. He says, I’m just curious about one thing. He says, who pays for the cabs?

Speaker I said, Well, I think I said, I guess most of times I do, because when he leaves in such a hurry, he forgets to take his money. And so he asked me to pay for the cab. And so Ziggy said, well, the next time he said, why don’t you just say, Bannerjee, I’m sorry, I don’t have any money. It’s your turn. You pay for the cab. So that night after the show we were going back was Connecticut and Hartford and walk out. And I said, Benny, I for we take a cab, I should warn you, I don’t have any money. I can’t pay for the cab. He said, don’t worry, this is on me. So he stepped out of the street and stopped the first car that came along.

Speaker And I put down the windows kind of doing this. I’m Benny Goodman. I play here in the theater. And the guy said, Oh yeah, I recognize you said you give me and my friend a ride to the hotel. And the guy looked a little startled, said, sure, get in. So when he got in the car or anything like that, this was on me. So he was funny. He very had a reputation about being funny with money. And he was in some ways. But first, I want to make very clear he was never dishonest. Never if he if he told you you would pay such and such, he paid it. He made maybe it broke his heart, but he did. And I there are a lot of stories about Benny, about being cheap or crooked or something. And I think those stories, maybe there’s some justification that he might be a little tight on occasion, but he was never dishonest. And just as an example of a funny thing about money is a one time my father had written to me, I sent a certain amount of money home every month. Anyhow, on one occasion, my father would write to me and say, my sister needed an operation. My mother did an operation.

Speaker My father gambled a lot and and he needed five hundred dollars.

Speaker Well, I knew, you know, he said your sister needs an operation, but I knew, but it’s my father. So if it makes him happy I. I didn’t have it. So I asked Benny, can you lend me five hundred, give me an advance on five hundred. At that time I think I was making 200 a week and he said, well he said, how are you going to pay it back. I said, well I’ll pay you back fifty dollars a week. And he said, well that’s ten weeks. He said, How do you know you’re going to be in the band that long. I said, we’re on the road where you’re where you have to give me a thirteen week notice so I can pay it back easily. He said, no, we’re going to be in California in eight weeks and that’s your home local.

Speaker And I only have to give you a four week notice and so.

Speaker Well that the hell so about two or three weeks later we’re playing in the Chicago theater but this time my salary has gone up to 300 and he paid us in cash and downing the dressing room, I put the money in my wallet and put it in my coat and took it up it off and put all the bad uniform and stupidly did not take my wallet with me. I just left it there. But you figure in the theater, who’s going to steal it? Well, somebody did steal it. I stole my three hundred dollars and I told Benny about it. I mentioned it to him. I didn’t expect him to do anything. He hit the ceiling. He went up to the manager of the theater. He raised hell. He said, what kind of place you’re running my you can’t leave their money in the dressing room and you should have locked it and everything. And and he said, I want you to check your place and find out who stole it. And then he went to the police department and raised hell there about if I went to the police, you know, around one of those where there’s never around when you need them things. And and he carried on, treated, you know, like I was simple minded son, which in a sense, I was I was very inexperienced in big city ways. And then after the whole thing died down, I’ve got two or three days, I got my wallet back, but police got it. And of course, no money. And Benny said, well, I said, I’ll tell you what, I’m going to give you another three hundred dollars. So, you know, I didn’t ask him for the money, in fact, I wouldn’t take it, I said, no, you don’t have to give it to me. It was stupid of me to leave it there. You’re not responsible for this? No. I want to give it to you. You wouldn’t lend me any money, but you give it to me. And the same thing. When I left the band in 43, I was going to go to work at CBS, but I didn’t have a New York union card and it took six months to get a card. And during that time, you cannot work and be coming out of a name band. They really kept their eye on me. I went out of town for two weeks because I’d had pneumonia and Benny invited me up to his country place to recover. And and the union found out about that and attacked another two weeks under by six months that I had to put in was stupid. But when I left the band, he said, what are you going to do for six months? And I said, well, I’ll try to get by, you know, maybe go out of town to a club date or something. I’ll let you a thousand dollars to carry it through, which would have been enough for six months in those days. Wasn’t enough. And he said he lend it to me. And then about a week or two later it was my birthday. And Gertrude had invited Benny and his wife over for dinner for my birthday. And he’s sitting there. Alice had given me some presents and. I barely said I didn’t bring a present for you, but I think I got one here, like I said. That he said, you know, the thousand I let you. And I said, yeah. He says, keep it.

Speaker You don’t have to pay me back.

Speaker And so it’s not only that I knew stories about him, how many kids he I don’t know how many kids he had in conservatory. Poor kids from Chicago. A lot of them would be relatives of his mother or cousins or something. But, you know, I know stories have lots of orchestra leaders who are well-off and they don’t do things like that. You’re putting all these kids through school or colleges or conservatory or just some kid that somebody brought to his attention that needed to go to school and didn’t have the money. He gave a ambulance to the Spanish loyalists and. Well, Bunny Berrigan got sick, we were playing in the Paramount, and I remember seeing if anybody’s wife coming every week on payday and he was giving up on his paycheck or giving. Well, I gave her cash in the envelope, the same as all the rest of us. And I asked him about it and he said, oh, but he’s been sick for a year or so now.

Speaker I’ve been I put him back on the payroll about a year ago.

Speaker And and I asked him, I said, you know, nobody knows this about you. They like to tell stories about you, how cheap you are. And Penny Pincher and I make a joke. I said, of course you are. But I said, you do wonderful things and nobody knows it. And he said, I don’t want anybody to know what he said. You have any idea how many letters I get from total strangers? People come up to me on the street and want me to give them money and get furious because I want to say, well, you rich, damn rich, you said, you know, you keep all the money, one of those kinds of things. And he said, abuse I take from people I don’t even know, let alone people I do know who think they should get money.

Speaker Well, we can go back.

Speaker Well, I ask Benny, you know, you’ve done so many generous things for so many people and no one knows you. You know, in fact, to tell you the truth, you have a reputation of being kind of a tightwad. And he says, I know that. He said I prefer it that way. He said, do you have any idea how many people want to get money from me? And he said, aside from relatives and friends who think I should finance every harebrained idea they have, he said, strangers come up to me and what I don’t give money. And they say, you stinking Jew or salvoes or something abusive. And sometimes it even comes. They try to attack me physically if I don’t give them money. So so I said I’d rather have that reputation than having people hit on me all the time. He said I, I give away my share and he said it’s my business is nobody else’s business.

Speaker There was not a good story about money you told about when you asked him for a raise and.

Speaker Oh yeah, I started out I think it was one hundred and twenty five when I started out and after about a year and I felt a little more secure and I was going to get married, I said I wanted to make two, I want to get a raise. And he said, well how much do you have in mind? We’re having breakfast on a train. And I said, Well I had two hundred dollars in mind because I’m going to get married and I don’t need that much money to pay my wife on the road with me. And he said, well, I don’t know. Two hundred dollars.

Speaker He said, you know, Harry James was making two hundred dollars when I fired him and I know damn well he didn’t fire him because I carry the cheque back to him that Harry said him. Benny financed Harry’s band and made a good penny out of a two. And the final payment on the band was when he went to Reno to Mary Alice and Irving. And I took him to the airport and he gave us the cheque to bring back to the put in the bank for him that he had forgotten and left it in his coat pocket. So several thousand dollars, I think several thousand was in the million. I think over that. And I had enough, Larry was sort of this was a better life for me in some ways, you know, aside from sitting in his chair and everything, trying to live up to him.

Speaker I had an experience in Cleveland. You know, the band was playing one night of there and Harry happened to be playing a theater there. And his musicians will do, you know, when they do a theater, they’ll go to I hear somebody or they have a lot of friends in the band. And his case is a band. He made famous help to make it famous. And so he came to hear Benny’s band. I guess he wanted to check on me because he took a chair and sat right behind me up at the bandstand. That’s not quite customary thing to do. And I’ve not always been the most accurate trumpet player in the world. I missed notes occasionally and sometimes often. And this night, every time I missed a note, he’d snicker. And of course I missed more notes and he’d snicker. And then he doesn’t like it. The best notes. Well, no leader does, but he’s vocal about it. So the intermission came and he called me into the dressing room and I came in. He says, What’s the matter, Pops? He said, you know, you’re missing a lot of notes tonight. I said, Yeah. I said, it’s just one of those off nights. Is something bothering you? And I said, no, I didn’t want to be, you know, a crybaby. And excuse me saying Larry makes me nervous. That sounds sort of chicken is so I just said it’s an off night. And he said that he knew what was bothering me. He said, Harry bothers you, doesn’t he? And I said, Yeah, I guess so. I said, you know, he sort of Snicker’s when I play. And I said, you shouldn’t let it bother you. He said, you’re a much better trumpet player than he is, that I could see the wheels going around his mind saying he’s not going to swallow. You know, that’s a little too outrageous, so he added potentially, and so I said, well, I’ll accept that. Well, that’s my favorite compliment. You’re better than Harry James potentially. And all I’ve lived on that. I better veteran everybody potentially.

Speaker I can’t get it straight. I won’t be able to get out my gun. I will try to mind our PS and Qs in the beginning.

Speaker Part of that story got a little confused or did it? It’s clear to me that the just because the punchline is that Harry James is making two hundred and. Oh, that story. Yeah.

Speaker Don’t tell about him setting Harry James up in business though, because that’s an interesting angle on Unbanning and his, you know, business sense and how the relationship was with the guys. If you can tell sort of the whole story about how Harry want to go out on his own, you know, and set him up and then he got a cut of the take.

Speaker Well, yeah, he lent him the money to start. He started. My question will be, that’s a start. Yeah. Harry James want to go out?

Speaker Well, Harry James, when he left the band, wanted he left because he was very famous and he wanted to go out on his own and start his own band because he is probably the the biggest drawing card of the band outside of Benny himself. And I think in view of that fact, Benny wasn’t too sorry to let him go either. And so Benny financed the band for him. He put up the money for him. He did that for quite a few people. I think later years that became part of the agreement. If you joined I know Cudi had the agreement that after a year or two, Benny had set him up in a band, which he did, and it failed. And but Harry, as you know, is very successful and made his final payment. And Benny had put the cheque in his pocket and he was on the way to Reno to marry his wife and to Mary Alice.

Speaker Good Alice to start again so we can get a little tighter shot, start to start with that, getting the final payment from Mary Jane.

Speaker Yeah, I bet Benny had picked up the final payment from Harry James.

Speaker I guess from either it was in the mail or from the agency and he stuck it in his pocket. But he was a little forgetful. And he apparently remembered Irving Goodman. And I drove him to the airport to go out to Mary Alice Hammond. And so he gave it to Irving to told him to deposit it in the bank for him. And so because we pride the envelope and took a look at it and it was a very healthy size piece of money and this was the final payment. And so apparently, you know, when you think of it, that arrangements cost about five hundred dollars apiece and the copyists, another one hundred and something. And you have to have at least 100 hundred arrangements to get started. And you have the lean years where you’re paying musicians a good salary if you want to get good musicians. It was a big out outlay. And but he put a lot of people into business. Teddy Wilson, who financed his big band.

Speaker And that didn’t last very long either. Unfortunately, it was a good band.

Speaker I didn’t have good arrangements, but he had good players.

Speaker And you also told the other day about your friendship with Benny would mean when you were on the road, you guys go out because you both like to play after hours clubs. Yeah, I felt a little bit about that. And the people too many know that, like you were working over many hours a day.

Speaker Oh, well, when I first joined the band after work, you know, I was playing parts and I wasn’t playing all that much jazz.

Speaker I was playing, you know, maybe every Saturday, maybe had three solos out of seven tunes. And everybody in those days like to go out afterwards and play. And in most towns of any size at all, there was always in the black area. There was always a little place called a chicken shack or the dewdrop and or something. And they’d have eight or ten piece band that had copied off the big band arrangements for a small band. And they were good bands and good players and really wonderful players. In a way you think about it was pathetic. This is the best these black musicians could do in those days. And and or you could go into a club where it was just a little jazz band, maybe five or six pieces. But you’re always welcome to sit in now, especially if you play as Benny Goodman band and you come in the club, it’s it’s a drawing card. The people say, well, how do you know somebody from Benny Goodman spending? So every night we go out and play someplace, at least I would. And Benny got wind of it. After a couple of days, you go out to play after work. And I said, yeah. He says, I’ll go with you next time. So he started going with me and Charlie Christian. He used to love to play and he’d go with me. And sometimes one of the other people in the band I just fell in, Gerry Jerome, sax player, like to go out and.

Speaker Of course, when Betty White walked into a club, it would be a big sensation and. You know, it would be a drawing card for the band, even to the point, after my first record date with Benny’s band and the first time I played all all the lead on that record date and my lip was literally almost Hamberger, my lips were bleeding from the pressure, the mouthpiece and against the teeth of my lip made it. You know, there’s a row of indentations. I started to bleed and after the bodies of my wife will trickle away and he sort of lassies want to go out and play tonight.

Speaker Yeah, let’s go. And he said, no, you want to go out? And I said, yeah, let’s go.

Speaker So we went out. Yeah. A funny sequel to that story was and about 82, I think it was because I made a joke every 30 years.

Speaker I work for you and it takes me 30 years to forget what a jerk you are.

Speaker And it was a big joke. I said when I left and I said, I’ll see you in the year 2010. And he took me to Denmark to play. And he was doing a broadcast for the German television company.

Speaker And in addition to playing with a little sextet, which I was playing with, uh, he was going to do was a concert, you blue orchestra or something, and he’s going to do Mozart again. For a guy who goes through hell before a concert, he’s trying out box after box of reads. He finally gets a clarinet player from the symphony to come in and say, is this really good? And this really is good. And the guy shook his head and says, they’re all good. Mr. Goodman is actually says, if you’re going to throw those out, please don’t you just don’t sit there and break up with to me, they cost a fortune if you can even get them here. And he said, oh, those are good reads. And so he was kind of miserable. And I was there for a week just for this one rehearsal and the one night performance. But there was a good little jazz band in there, Papa Bush and his Viking. Do all these Vikings or something. Probably was a Danish band and a wonderful Louis Armstrong type player, very generous. Let me play a lot of solos. And, uh, and I would sit in was a very nice play all night with a band. And afterwards we like, give me a bottle of snaps and pay and, uh, and naturally I’d share it with a band. And when he got wind of it and on the plane coming home, he came back from the first class where I was sitting and said, Pops, he said, were you playing every night in the Tivoli Gardens? And I said, Yeah. He said, Would you do that for Jipé? I said, No, I’m doing it for fun. And he said, just like we used to do. And I said, Yeah. And you look very wistful. Was it fun? And I said, yeah, I was a lot of fun. Gee, I wish you’d told me so. Even as late in his life is 82. In 1982, he was still wanted to play and I would never dream to ask him in those days. But because he had changed his lip, you know, he he wanted to play like Reginald Powell. He had a great admiration for him and he took some lessons from him and getting to the technical scene when he used to just put the clarinet in his mouth and blow and most vital dynamic sounds. It was electrifying sound and he could play over a whole brass collection. Sound great. And Reginald Keller is a very quiet player in the technical thing. Was he a in both flips and puts the mouthpiece over both lips? Very, didn’t he? In fact, his teeth were rounded here with a clarinet mouthpiece was through the teeth and he’s telling me he spent day hours and hours and days and days and months trying to get that. I’m sure he said his lips used to bleed every day till I finally got that, I’m sure. But for my taste, he still musically was great. But that vital tone he used to have was gone. And it’s because he was using that this tragic thing that that musicians get maybe other people, too. But the other other bands, Guardedness Grieder, and he loved the symphonic world. When we were going to Russia, he said he was going to do the Mozart with the Russian symphony with. And he said, well, I got an idea. Why don’t you do the heightened trumpet concerto with a bushfire?

Speaker So I said, I think it’d be better if just you played the thought of it makes me sick to my stomach. I know.

Speaker But, uh, let’s go back to talking about, uh, some of the drummers you’ve spoken about. The war made a difference in the band you love. Uh, just cabinet. You know, I’m sort of sad story of benefit from that you said.

Speaker Well, we had a lot of turnovers and drummers, in fact, well, when I joined the band Nechvatal, I think my my question was still going when you started talking. So just, oh, we had a lot of turnover of drummers, especially in the band. And when I joined Nick for Tool is still playing with a band. But many times when he would have Lionel Hampton playing drums, loud was a good drummer. I always liked him and the same thing. Or Fletcher was playing piano when I joined and. Well, I don’t remember we had quite a string. I can see their faces, but my memory is not that good, but the two that were the outstanding drivers of my two favorite, Dave Tough and Big, Sid Catlett and of course, Benny, we used to do what they called give the race.

Speaker And that is you sort of stare at them and mainly at the drummers. It was very unnerving for anybody, but it’s damage suffered especially. And the other problem was that Benny would change the tempo if it wasn’t the tempo he beat off and he had a good sense of time, he would start trying to pull it down to his tempo and Sid would fight him or any other drummer would fight him, for that matter. And it got sometimes toward the end that Sid would sit there with tears in his eyes up so upset because he thought Benny didn’t like him, which was surprising considering I used to watch sitting in the train a little exercise before bed. He’d reach up to the bars on either side of the birth and himself like that.

Speaker And the average strong person couldn’t start to do that. And he’s a powerful man. He could have thrown Benny out the front door, but fortunately he never did. And the same thing, Dave Tough was a little more hard. I guess he was very philosophical on his sort of well, if he doesn’t like it, too bad I’ll leave. And so he did. But their time was wonderful. When Sid came in the band, it was for me it was like opening up. I never played better in the band because he seemed to know everything I was going to play when I playing a jazz solo and set me up for it.

Speaker You know, Bob, some little thing you do that make it fit. And I used to wonder that he did it. And then I realized he’d played with Louis so many years. Of course, he knew what I was going to do and.

Speaker And and.

Speaker There’s something else about drummers that was bothering me.

Speaker Got a minute? Well, I think you should take your time. Oh, the thing about the ray, you told him the ray. That was what it was. I also like the medium.

Speaker I used to spend weekends out of this place. We’re playing in New York. My wife and I would go up and spend the weekend there. And so I got to talk to him a lot over the years.

Speaker And I asked him about that Ray one time at supper and said, you know, you stand up there and you make the guy is nervous. Why do you do that if I don’t do anything? He says, I’m standing there. He says the drum platforms go up there at eye level. I have to look someplace. I look at the drummer. I said, well, you know, for at least 10 years, the drummers think you’re giving them the ray. I said, so do the other guys in the band. And of course, the reason for that was that his glasses used to be filthy and people would think he was looking at them, but he really wasn’t. Ziggy, you frequently would go up to him on the bandstand, take his glasses off and clean up or put them right back in. But he just sort of stand there like like it was a natural thing to happen and then sort of giggle and wiggle his eyebrows.

Speaker And then he had a funny laugh. You know, you go like that and his eyebrows would go up and down. One time he came over to me and said, Hey, Pops, you got a job? I said, well, I got a half a pint of brandy. He says, Let’s have a drink. So I went out on the wings and he took a little sip and gave it to me. And I started to take a little sip people. And I said, that’s enough. Then he took another little sip, put the cap back on, put it in his pocket that we did do that with cigarettes, too, incidentally.

Speaker And so the rest of the night, he’s up there skipping around, going through the body language. When he plays one leg up and twisting, I never know what to do, how he played and never fell over. He was a wonderful athlete, sidetrack and keep looking at me and wiggling the eyebrows like, oh, boy, we got fun on the way out. He gave me the AllVoices. Tomorrow night I’ll bring the jug, a half a pint, a little bit more about him being a great athlete. Well, the main thing I was thinking about was he would take tennis lessons and wind up being the pro or same thing with golf. But the thing that made me realize that I should have known his finger, you know, his finger control and flexibility with fingers was that he had marvelous coordination. We were in his place in the winter and there was a patch of ice going down a slope that must have gone down 50 yards. And I was not walking on a patch of ice with Benny’s sometimes doesn’t look where he’s going. And he started out on the ice and he started to skid. I was sure he’s going to fall and crack his brains out. He danced his way right down at fifty yards of ice. It was one of the greatest piece of footwork I had ever seen and caught the ball. I mean, look, I’m sure slippery what and I’m told about Cudi joining the band that your service.

Speaker Oh, yes. Well, I think directly, really. I had an old crank up phonograph. I used to carry on the road with me and right in the bus and I had a box full of records, my favorite records, and I cracked the phonograph up, play the records. They didn’t have tapes and you could put on earphones and nobody seemed to mind. And Irving at this time was writing with man, could this record of Concerto for Cutie had just come out to that later became do nothing to you hear from me? They put words to it and it was better, as could his concerto.

Speaker And it start again get a little a little tied in with the fact that here was Cooley who first told you to play the trumpet player.

Speaker Oh, yeah, yeah, man. Yeah. That was sort of the biggest star really in jazz about. Oh yes. Well, I was going to do that, I’m sure. Do you.

Speaker Yeah, that’s what I just want to get in and get it. Yeah, that’s good.

Speaker Well so we used to play this record over and over and over and start again and we had to wind up.

Speaker I used to carry this phonograph and my record. My brother was still there. Oh, we travel on the bus. I had a wind up phonograph. I carried a suitcase full of records and I’d play records on the other bus as we traveled along sometimes. And Irving sat next to me and I just bought Concerto for Cutie and we kept playing it over and over. It must have driven some of the guys crazy, but no one said anything. Finally, Benny came back. Benny always made the trips with the band. He was very Democratic. He didn’t go special. And he said, Who is that? It was Irving. So I looked at him, said his Cootie Williams, and he said, Yeah, what banzet that I said, Duke Ellington. Yeah. I came back a little later, said, Play that again. He played it again. So then we went to College Academy and he went to the hospital and everything. Next thing I know, it’s cool. He’s coming with the band. And when he started the band up again, it was a short while. Well. When he left Duke, we had red alert and then he came in the bag, which for me was a big thrill. Ten years later, I’m sitting next to the guy at first jazz player I had ever talked to was Gordie, and it is giving me advice about how to be a good jazz player, a good trumpet player and everything. And 10, 10 years later, I think, my God, I can’t believe this, you know, sitting next to Cody.

Speaker And not only that is we on the road were roommates. Normally I never roomed with anybody, but it turned out that I in many states I had to, so I couldn’t be choosy. I always roomed with him because I wouldn’t say, well, I rule with you because you can’t live in the hotel otherwise. But we had to do a manager who knew nothing about the black hotels and we’d go into I Ohio or Missouri or some of those states which were still below the Mason-Dixon line. And and there would be no place for black musicians could stay. So could he told me, you go in and register for the two of us and I’ll carry your bags up like I’m a bad boy. And I said, no, no way. I’ll carry my own bags and I’ll register for both of us. So we did that and so we’d go up and take the room and he wouldn’t eat in the restaurant either. So we had to have room service. And fortunately, all the waiters in the room service were black, so we’d ordered steaks could he’s a good eater.

Speaker And but after the first time, they came back with a second helping. But after that we’d get two or three steaks. They turned and we’d signed the check for for the dinner and had two hamburger sandwiches or something like that to about a forty dollar dinner. And it would charge to charge us because they were black guys and they knew what the score was. Why could he was in the room eating room service and who used to give me all kinds of advice when we would ride on the bus. I was about to get married. He said, Where do you get married?

Speaker He says, My wife doesn’t know nothing. My name is Charles Williams and said the first dinner, no matter how good it is, take the plate and throw it on the floor.

Speaker Get up, go out and eat the rest. From that time on, she’ll be a good cook. And I know his wife is a good cook. And I asked her, DeCoutere, it’s the food on the floor and she could shut up. Shut up. Oh, say I said you walking down the street, she sees a jewelry store pull down the stairs and let her look at the washing machines. She had all kinds of great advice about marriage. There was nothing. But my name is Charles Charles Williams.

Speaker Um, you also, I think one of the books quoted is talking about how could he really appreciated being in Venice? Bennett had been talking, you know. Oh, yeah. And he had stolen them. And it was a scandal that he left his band because Duke’s band was the greatest.

Speaker And I don’t know how I could do that. I asked I said, how the hell would I would you leave the Duke Ellington band to come to play this Mickey Mouse band? And I had once been fired because I told Benny that I will come back to this. All right. Let’s this one again. So I asked him, I said, how could you ever object?

Speaker I asked you, how could you ever leave Duke Ellington’s band and all that marvelous music and great musicians to play in this? And and he said, well, he said this is the best band I ever played on. And he told me this years later when we went to Catalina together with the Ellington band. And and then at that time, he told me what he meant by that. He said, when we have a rehearsal, everybody is there. They’re there all the time. When we go to work, they have the right band uniform. The uniforms are clean and pressed. We’re gonna show up for rehearsals. When he rehearses a band, he really takes care of business. He was put up with any funny stuff when he was strict on rehearsing advantages to digress a little bit. You could not smoke, chew gum or sit with your legs crossed or talk and we’d have one new tune and we’d go over it from start to finish for one hour and he’d tell the rhythm to keep going that maybe he’d say, now, do it without the rhythm and he’d count it off. And we could both at the same time do it again for four or five times. Then he’d say, play everything straight.

Speaker Eighth notes like doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo. In the next time dotted 816 doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo.

Speaker By the time you get on the bandstand, you don’t know how the hell I play it. And it would never matter how I played it. It was wrong. You said, why do you play it all straight A’s notes? I said, that’s why we did it. Rehearsal. No, I should go get it out at another time. Say what do you all about it enough. What should be doo doo doo doo doo doo doo. But anyhow. He admired the fact that Benny knew what he wanted more or less at rehearsal, he was in charge. He didn’t have 15 guys telling him what to do or anything like that. But it was a great thrill to go to work with Groody and the.

Speaker I always admired him.

Speaker And years later, I worked with him in Carnegie Hall on a repertory company for George Wein and the Summer Jazz Festival thing, and we’re doing Ellington stuff and doing Ring the Bells came time for could easily play our solo. So you played Scutti solo and ring the Bells and I said, That’s not my soul. I said, yes, it was. And he had made two records of it. And I explained it. He said, Oh yeah. He says, you’re right. That was the only record I was always telling me play our solo.

Speaker He was very generous that way. He didn’t mind the fact that.

Speaker OK.