Speaker Well, we started what we call the Tavia project.

Speaker With the three.

Speaker Short stories, Raychelle Mowlam, which are basically simple monologues written by spoken by the character called to appear to the writer, actually. The originally when we were looking for those stories, Shellback, I was I it was out of print and I finally found a copy of those stories and I have an old bookshelf. I had I had heard the stories first from my my father in the original Yiddish, and I dimly remembered them. What I remembered maybe was that I was amused by the central character, the the milkman. And so I thought it was worth exploring and that was the genesis of the project. But what happened was that Jerry show shelter and I fell in love.

Speaker With the concept of doing this show, although although the three of us were fairly well established on Broadway by that time we were able to approach any producer in town, we thought better of it, that we did go to any producer at first because we know what the reaction would be. The you know, you want to do a musical about a bunch of old Jews in Russia who are going through a program.

Speaker I mean, whether you out of your mind, you know, so it was our baby and we worked out that on and off for a number of years. You know why we’re doing other things?

Speaker You know, just going to interrupt you for a moment. I just like to ask you a little bit about where it was and when it was said and a little bit about that time in Russia.

Speaker Well, the stories, as the the fiddler said roughly around the turn of the century, around 1900, it was shortly before. It was about the time of the major exodus of people to America and the Jewish exodus was came around that period. So we said at that time and it was roughly the time of the stories, why were people coming to America? Why did you come to America?

Speaker Why did the Jews in Russia come to America? What was what was happening?

Speaker Well, they were they were escaping from a very difficult life. And in Poland and in Russia, they were.

Speaker At least second class citizens, maybe third class citizens, and they had no real rights and they were under the threat of a program at all times, that was some major, major programs during that period. And so they went there like all like all immigrants, including today, to make a better life for themselves and their children.

Speaker Now, you you found this in a bookstore and you took the idea to bargain hard again, what was their response?

Speaker Well, they explore that ad after with after some discussion and conversation among the three of us. They found it sufficiently intriguing.

Speaker I think one of the factors was that. It touched something in all of us about our backgrounds, because all of us, to one degree or another came from that kind, we had ancestors who came from that kind of background. I know that the Reverend Jerry Robbins got became involved. That was a very important factor to him. That was a very personal kind of show.

Speaker And I ask you about that in a minute or so. You took the idea then to a producer and maybe even the director. And what was his response? Just if you could just remember.

Speaker Yeah, well, we didn’t take it to a producer, a director until we had a substantial part of the work done. I had I had constructed the show scene by scene so that we had the whole total and they had written a fairly complete score before we showed it to anyone. And I we know that. It was a very delicate kind of project, and so the first reaction we got from producers was what we kind of anticipated. You know, I remember one producer saying. You know, I kind of like it, I like it a lot, but what am I going to do for an audience once I run out of Hidatsa benefits the story I’ve told often, but it’s also true. It’s not apocryphal. So. So we had we would turn down a lot. We finally there was one producer named Fred Coe who was enormously intrigued by the project, and it was curious because of all of all the producers in town, he was the least Jewish.

Speaker He was a Southern Baptist.

Speaker And I remember his father saying to me, these people really exist, that they I mean, these are not invented people. I said, no, no. I said that they come from my parents coming from that kind of community. He says it’s fascinating. He says it’s a very fascinating thing to write about.

Speaker Anyway, he was the first producer who is interested in the show, but unfortunately, he was unable to to get it on financially and otherwise.

Speaker So then you took it to health.

Speaker So and so, so as a result, well, we had to approach health first because because helprin’s because we all had worked with him at one time or another and were very fond of him, and he was a friend of his. His first reaction was, was what I had described. He said he did not think it was a commercial commercial show. He did not feel very comfortable with that, with the material. It was really foreign to him. And it was only after Jerry became interested that he took another look at it and decided that he would like to become involved.

Speaker Is it true that if you could just also try, if you can, as we talk to differentiate between Bach and Robbins, because that’s a little built-In confusion we have here. Is it true or not? He he sent you to Jerry, didn’t he? Can you tell me about that?

Speaker Well, no, actually, I think I think Jerry originally heard about this project from his friend Steve Sondheim. And Steve Sondheim had heard the material. We played it from friends at my house, other houses. And Jerry Bock played the score at one occasion when Steve was there. And Steve Sondheim, I’m sure, talked to Jerry about this. And as a matter of fact, when we approached Jerry, his first reaction was, why did you wait so long? He was what he had heard from Steve Sondheim, apparently intrigued them. And that was how Jerry became involved and Jerry and when Jerry, I think. Of course, this is kind of Rashomon, you know, but but because we go back a long ways, but if I remember correctly, it was where when we told Hal that Jerry was intrigued about who was interested, that he became very interested in the project.

Speaker I think that’s true. Um, was that the first time you met Jerry?

Speaker Yes.

Speaker OK, so tell me your impression of him.

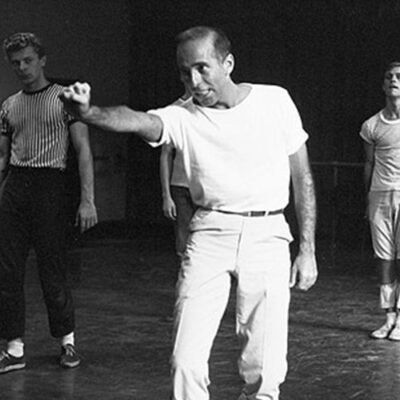

Speaker I mean, my original impression will have the impression about him before I met him because he was widely known in the theater for certain attributes. He was a very strict disciplinarian. He was a perfectionist. He was very rough on people. He played favorites and among his casts. And in general, he was not easy to work with, but he was kind of a genius. So, I mean, that that all of that I knew. And when I was first asked about about Robin’s becoming involved, my first reaction was being very uncertain because I thought. From what I know of Jaryd, life will be difficult, but as it turned out, as far as I was concerned, it was a very positive, really positive experience. I mean, we had our little ups and downs, which were never normal. But he and I got along very well, very well. I cannot say they got along very well with everybody because he didn’t.

Speaker I think sometimes people who are not working in the theater think of the director as some kind of a traffic cop, but that is certainly not the case with Jerry. Moving people around the stage is just a small part, I think, of what he did. So could you explain to me, you said that the script was written, but I think Jerry was very involved in how it was developed. Could you tell me about.

Speaker Yeah. When Jerry came came into the picture, we had a fairly complete score and script. And as a matter of fact.

Speaker We never we never deviated from the line of the of the script. These think that we started with, we finished with, but we made many, many changes within it all along and a lot of them were motivated by our conversations with Jerry. Jerry kept asking the question, you know, what is the show about? What is it about? And he was like a bulldog. And I had a lot of answers to it. And, you know, it’s about the conflict of cultures. It’s about that throughout this slow disintegration of sort of a of a society, it’s about the difficulties between parents and children.

Speaker All of those things are involved.

Speaker And in talking about them, the word tradition kept coming up.

Speaker You know, it’s the tradition of this community that so-and-so in this community, traditionally they so and so the word tradition was part of it, of all the answers. So at one point, I assume he was one of us said, you know, if it’s about tradition, let’s say so. And that’s that’s how. We we the they we started the show with the sword tradition, which was, I think the last so I’ve written. After all of the other songs were written in the course of the work, of course, he did a lot of work for a better word, I’ll say anything he would.

Speaker He worked differently from any director I’ve ever worked with. He would take a seat and say, I like the scene very much. Can you change it? Can you do you think he can improve it so that I frequently would take a seat and rewrite it right from a different point of view, emphasize different characters or whatever. And he’d look and he says, this is really very good. I like the first one better. And so we went back to the first one and it happened happened time after time. But sometimes you say, wait a minute, this third version you have here, there’s one line I kind of like to keep, you know, something like that so that he you worked much more and much harder with Jerry as a director than you ordinarily did.

Speaker And of course, it was worth it because that’s the way he worked.

Speaker So what do you attribute that kind of constant? Sheldon said he was the world’s greatest district attorney. That kind of constant questioning. Is it good enough?

Speaker Well. Well, first of all, that was his technique. That’s the way in which he tried to get the best out of you. He did that for the actors as well. Also, there’s a strange thing about Jerry because Jerry. To my mind, had a good deal of insecurity, he was not sure of anything, really. One incident occurs to me in the second act of the show he had. He had to choreographed a very elaborate ballet. Which appears right after the character Carver has agreed to marry has decided to marry out of the faith.

Speaker And it was it was a long ballet. It was a beautiful ballet, and it stopped the show dead to my mind. So everybody’s mind, we just felt that the show. Just stop there, and we kept saying that’s that that ballet is there that way. It’s too long and I serves no real purpose. Well, he kept cutting it down, he cut it down, it was still too long, it was short, but so eventually I think I was I was well and said, why don’t we try it one night without a paddle and just use that little tag and that little little thing that have things he says, well, I’ll try it, he said. And I think it was very reluctantly because he had worked very hard on that ballet. I’ll try it one night and he did. The show improved enormously. And then he says something that I thought was very significant. He said, you know, I don’t know that they can ask, where is the ballet? Where is the Robi’s Ballet in the second act? I said, I don’t think they can answer that. I think the answer is a shocker.

Speaker Those are so not good. I says, well, he was worried about how he would come out. So and that was very typical of, I think, of the way Jerry felt he he was very eager to to protect his. His turf.

Speaker Let’s go back to the beginning of the show. What do you remember about the construction of tradition? You said it was the last song written.

Speaker Well, I think I think it was the last song written. I think it was written just before we went into rehearsal. Or maybe we were we were already in rehearsal. And it was written on the basis of, as I said earlier. On the basis of all our conversations that that this show is about traditions and each of the episodes in this show reflect the breakdown of age, what tradition after another. And and then Jerry Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick, you know, wrote the draft and we went over it. And Jerry made a lot of said Jerry Roberts made a lot of suggestions and so did I, I suppose.

Speaker And so that I suppose Zero Mostel, whether he was whether he was presented with the material, he loved the material, he loved it. And I think he made some contribution to it in developing it. And that’s how it started.

Speaker What do you remember about how Jerry constructed the opening number?

Speaker Where once we had and once we had the the then the number, the tradition, no, he decided that he would construct that he was able to construct the opening built around that number. In other words, it was a way of presenting all of the major characters. And so I wrote the dialogue that was needed through to introduce all the characters of Yente the Butcher and and the sons and daughters and so on. And he constructed it like a jigsaw puzzle and he put it all together.

Speaker I remember something that Paul Richardson once said to me. He was to drift away a little. He. He and I were watching for the first time. Jeri’s.

Speaker Dance, the the battle dance as part of the arts, part of the wedding dance, and we knew neither of us had seen it before and I was waiting for a reaction and are saying to me, this is a guy who can do that kind of work.

Speaker You have to forgive him anything. And I knew exactly how he felt. And I felt the same way because we were just bowled over by the excitement and brilliance of.

Speaker Did he tell you what is the inspiration for the bottle dance?

Speaker Well, and I know that he had that he had been inspired by by the bottle dance, by going to the someplace them, because I went with him, I went to some kind of wedding, a Catholic wedding, and he saw that he was very taken by the wildness of the dancing, the the kind of madness, because all of these people were dancing to music that they heard in their heads.

Speaker Each one was dancing individually and one man was dancing with a bottle on his head.

Speaker I saw it and I thought that was interesting. But that’s all I thought he saw it and he saw dance. So what’s the difference between me and Jerry Robbins?

Speaker Um, you talked before the jury talked to you, as I understand it, when you were constructing the show.

Speaker About the need for. To avoid nostalgia. Avoid sentimentality to make those all Jews what?

Speaker Well, Jerry always insists the avoidance of nostalgia and the show, he did not want one to feel like a Second Avenue Jewish show NATHER that way. That was never our intention. But Jerry emphasized that. And he he wanted those people to be tough, hard working. In some ways, ugly, I mean, not not at all romanticized. And by and large, you are particularly beautiful or romantic, so it worked out fine, but actually what he wanted was parallel with what I wanted. I certainly didn’t want that get that kind of Second Avenue feel about this show. So, you know, that worked out just fine. Jerry had a very I thought Jerry had a very interesting attitude towards Fiddler.

Speaker It was not just another show to him. I mean, he had done major shows before, fitly had done for the second straight year the gypsy. He had had big hits. But Fiddler was a very personal experience to him, as it was to me and as I was, I think, to sell to the Jerry Buck because it did reflect our own ancestry. And to Jerry, I had a great deal of meaning, I thought. And so. He was passionate about the show in general, I guess he’s passionate about his work, he’s always so passionate about his work.

Speaker But this was a kind of extra element that was that that meant that Fiddler meant for him. It brought.

Speaker It was a reaction to his feeling about his father, about his parents, whatever as it was to me. And so I understood that it’s a matter of fact. I also remember I’m skipping around a bit of you know, I remember that after the show opened a day or two after the open, Jerry called me and then kind of an odd voice.

Speaker He said, did you get the kind of reaction from your friends that I did? I said, What do you mean? He says, Well, they thought well, they said, it’s a wonderful show. They know that not they, you know, complement the other work. But they were like and it was like a religious experience. And that’s exactly the way I felt. I said, yes, that’s I got this very all these people say I never felt this way in the theater. I cried, I laughed, and I felt that this was a very personal thing. It was. And he talked to me about it as I felt that this was really strange, you know, not at all. What the what you usually get when you have a successful show, people, you know, call the usual compliments, mentor unbent. So so and that was that was this show. This show meant something very special to Jerry.

Speaker Did he ever talk to you about when he was a little boy and he was taken back to the shtetl?

Speaker He told me about it. I don’t think we talked. We talked about it any great length. But he said, you know, he says, I was I saw that that that community once when I was a little boy. But we didn’t go into any great detail about it and talk to you at all about his recollections. Not really, no. I think he may have spoken to either Jerry Berkowitz, Sheldon, but he did. We were not on very intimate terms. You know, it’s not it was never easy that we get to be intimate with Jerry Robbins. Jerry was not a hail fellow, well met fell guy at all. You know, he’s no slap on you on your back kind of fellow or a hug when you come into the office. He was kind of cold and standoffish and with some people, he was downright hostile.

Speaker I mean, his relationship with Sierra myself is not exactly the.

Speaker Affectionate.

Speaker Well, there was a history there, right?

Speaker Well, the history, so which, of course, we were all aware of, they had worked together and in another show, but their history really came back to the blacklist. So zero.

Speaker We have a permanent anger about Jerry and Jerry was aware of it. And sometimes it was hard for Jerry to talk to zero and zero spoke, spoke of Jerry, even though I think he respected them, he spoke of him with the degree of contempt, but that was zero. And sometimes I found myself as a as a as a mate, you know, as an intermediary between them. Like Jerry. I mean, zero would do some kind of a reading which Jerry says he didn’t like very much. And he said to me, would you talk to him about that? And I would. And I would say, I come from Jerry. I you know, I say zero. Don’t you think we better off it the way it was written, you know, and with that kind of feeling. And he’d say something nasty like, get out of my way. You know, when I’m on the stage, it’s between me and the audience. So but he’d do it. He’d always I mean, yeah, there always was was a pro and his way he wanted to do it. Right. So he’d listen, he’d insult and listen. So but as I say, I frequently was in the position of acting as an intermediary between Jerry Robbins and Zero Mostel.

Speaker Can you just give me a little background? You said it it had to do with the blacklist. Why why was Zero so angry about that?

Speaker Well, Zero was blacklisted and Jerry had named names, and that’s enough to talk to to start a fire. And zero zero would never forgive anyone who name names. Never as. And and that was that was the basis for their relationship, really. However, they each recognized the talent of the other zero, belittled Jerry Robbins all the time. But behind that, he knew that Jerry was doing a fantastic job.

Speaker Are you familiar with some of the homework that Robbins did, you know, he was a PE, as I understand, a lot of homework for a part, and talked about the Hasidic wedding. What else did he do?

Speaker Well, he was very well. Jerry Robbins was always very well prepared going into rehearsal, and he did a lot of homework.

Speaker He, aside from you, couldn’t do very much research because that community did not exist. The the only research I was able to do there was barely remembered for my father. And it was a book that I consulted a lot. Life As with People was the name of the book. It was published by the by Columbia. And thank God for it because it was all about the dying shtetl. But otherwise, the only research we could do well, there were savings from whom we visited once. Lowell Jerry did more than once I guess, and the other was trying to make each scene feel as real and true to those people as possible.

Speaker I read where Sheldon said he talking about Robbins’, he drove everybody crazy because he had a vision that extended down to the littlest brushstroke in the scenery and the triangle part in the orchestra. Did you find that to be true? And if so, what? Can you give me some examples?

Speaker Well, he did have had a vision. He has, I think, I guess in all his shows and I would agree with what Sheldon said.

Speaker He he cared about every part of the show. He to on the other hand, he used to get. Irritated and and annoyed and sometimes walk off and says, I’ve had it, you know, enough, enough with the session, and he would pick brains, for example. If he was casting people, he would cast people and have them come back, even though we all knew this person was not going to get the part.

Speaker He thought.

Speaker Maybe the audition hit show. Show me show or something and he could use. And he did that and there was a kind of exploitation, which, of course, the actors, I guess, didn’t mind because they liked auditioning for Robinson and Park and how they can Stijn or whatever. But but it was a kind of exploitation. But he did that. He also, of course, played favorites. In the cast, there were some people he liked very much and some some he didn’t like at all. That was one member of our cast whom. Can we cast reluctantly, we are like her. He couldn’t find anybody that that represented his vision, so he went with her reluctantly. And made her life hell. And kept saying to me, can’t we cut some of her lines that she had too much to say? And once I did cut one or two lines, I said, Jerry, I don’t want to ruin her character.

Speaker He says, well, do the best you can in parenthesis to rule that character, I suppose. So I’m going to tell me who that was.

Speaker Yeah, that was a character, Viento. It was Bea Arthur. Oh, B, B, I mean, B would not be happy at the name Jerry Robbins and the other hand, and he was very protective of the woman who played the Goldar who had never played this kind of a part before, who was basically a ballerina, but who is familiar to to Jerry Maria Kornilov and who ended up doing a brilliant job as as Golda, but starting off not knowing exactly what she was doing because she had never, never played a serious part before on the stage.

Speaker Before we go on, I wanted to just go back because we skipped a little something that I wanted to ask you, Jerry, I think early in his life had some conflicted feelings about his being Jewish. He wasn’t always thrilled to be a Jew. And I’m wondering, first of all, if he ever talk to you about that. And I’m also wondering, in your own experience, when you were a young person, what was it like to be a Jew here?

Speaker Well. It was a privilege to me, I mean, I grew up in the Bronx, in the Jewish neighborhood, so it was our gang.

Speaker I mean, if I had been an Italian kid in that neighborhood, I would have been in trouble. No, I I grew up in in a Jewish household and in a Jewish neighborhood and the Jewish environment, I went into the theater, which is not exactly a a a non Jewish area. So I never really have any any problem with Jerry. Never spoke to me about it. I think Jerry’s Jerry’s concern was that he felt like an outsider in general. His sexual orientation at that time was a very delicate issue. And out of that came possibly his concern about his religion and and whatever his height knows. So because he was not tall, I think he would have liked to have been tall. But I have no such feelings about being about being Jewish, but whether they had been Jewish, sir. Where did you get the notion that I’m Jewish?

Speaker Just a wild guess. Very good guess while it takes one to know one. Um. I understand that. Do you love me with Jerry’s favorite song in the show, talk to you about that. And why do you think it was?

Speaker Well, do you love. I don’t know why. What do you love me? Came to rehearsal, actually, and it came at. The scene was there. And they you know, that they have a I have a brief scene between the husband and wife and they developed the scene, the song, and it was very touching.

Speaker It was very, very easy to to to stage and. And it added a kind of spice to that second act, that kind of a. And in a way, it was the most romantic moment in the show, despite the fact that we were involved with three daughters and that and their boyfriends, this felt most romantic because this was an older mother and father who finally recognized the word love. And I can see how it was.

Speaker In a way, it’s my my favorite moment to I have many favorite moment, but that’s the way high up on the list.

Speaker I occasionally say to my wife. And she occasionally reacts to what we call the.

Speaker Right, tell me what Jerry is a collaborator. What was he like?

Speaker Well, he was he was Jerry as a collaborator is a very strict disciplinarian. He he’s a demanding person.

Speaker And you either go along with him or you fall by the wayside. Actually, I enjoyed that because I loved the work. I mean, Jerry was devoted to this project and I was devoted to this project.

Speaker So we got along just fine. But if you if you didn’t accept his kind of discipline, you were in trouble with Jerry.

Speaker Did he was he solicitous of everybody else’s opinions and thoughts?

Speaker I don’t think he begged for anybody’s opinion. I think he he expected that we have opinions, we would express them and we did well during that period of a couple of months before we went into rehearsal. The four of us, as Jerry Bock and Sheldon and myself met with Jerry and we talked about absolutely everything connected with this show. Everything, I mean, including none of the characters or the scenes or the signs, the sets and everything. And we all expressed our opinions very freely. But he was, you know, basically the captain of the ship.

Speaker I heard at one point you to stop talking. What happened?

Speaker You know, I don’t remember that I, I, I, I literally don’t remember I remember that’s at some point I got irritated with Jerry because he kept asking for a scene to be rewritten over and over again, like I’m tired of it, but I don’t remember, although I am told by Shell that I guess that we stopped talking. I don’t remember ever stopping talking to Jerry. You know, there were times like that. I was irritated and so was everybody, you know, working and the great and the for any length with him, it’s inevitable. But we’re going to change. But oddly enough, unless I unless I’m out of my mind, I have a very good relationship with Jerry.

Speaker What was it like casting a show with Jerry? Did he like you? Did he have to see something right away in a performer to get interested? Or did he like working with people during auditions?

Speaker Well, Jerry, I’d like to see something from when he was auditioning. He would love to see something from the performer right away. And at the same time, he would like to work with a performer and he would do both. And Jerry as I. Jerry, frequently. Took things from the performer, which would to him unexpected and and use them as part of the character, even though that performer was not necessarily cast for the show. And on occasion, he would he would audition someone even though the part was already cast, because he thought that person might show them something that was usable in the audition, which I thought was slightly not exactly illegal.

Speaker But but. What words, they say.

Speaker Not nice, on the other hand, of course, the actors, though, did that, even if they were aware of it, they don’t mind it because they love showing what they had in case any of us could use use their services later on, whatever. Jerry was a very careful auditioner and sort people over and over again. With the possible exception of myself, we did see other characters for the other people, for the character of Tavia, I remember seeing Jack Dulfer there and there were others. But all along we felt that zero had the right quality for the part and there was very little argument about that.

Speaker Jurors said that Roberts said that he wanted to make the cast like a shtetl. How did he achieve that?

Speaker Well, he wanted he did not want to cast pretty people. He wanted cast people who looked like they were work as hard workers and and tired people. And he cast it that way. The only ones who are attractive and only reasonably attractive, they were not the world’s great beauties with the three daughters who naturally as young girls would be attractive, but the boys would not. Their sisters were not necessarily attractive at all. So that’s that’s what he meant in terms of casting him once the cast and like people from the state law rather than people from central casting. And he did and.

Speaker These are all things that we all agreed upon, it was not like he said something, we said, oh, no, let’s get those gorgeous girls. You know, we we all felt that way. We all felt at this. All shows we worked on had to feel true in every moment. And I very often would cut a line that would get a laugh and I knew would get a laugh because it somehow rang slightly untrue.

Speaker Maybe we took no chances and and we we cut whenever we felt did that boy.

Speaker I also cut scenes which I thought would play brilliantly, but the but they did not they did not advance the story enough or at all. For example, I remember a story I wrote in the very first scene. I wrote the very first version of Tevye playing chess with Pertschuk and and of course, of which we get a sense of their philosophy of life, their attitude towards each other.

Speaker And to my mind, there was a delicious scene and there was a kind of delicious scene you throw out, and we did them without any moment’s hesitation. The same thing was also true of a scene that we had to be. I think we opened with it. I’m not sure. We certainly went into rehearsal with the opening of the second act was a scene that we called Leatherface from America, in which Tavia has received a letter from his brother in law in America describing life in America.

Speaker You know how he’s living in this gorgeous house they call a tenement, you know, things of that sort which will play a role, particularly because there are a lot of laughs and they’re all loved it by. It gave us nothing but a lot of laughs. And I mean, it did not in any way strengthen the story and move the story along. And to paraphrase Jerry Robbins show, is more of the breakdown of tradition. So it went and and when those when those scenes when they went without any any tears at all, we said great together that gets in the way. And that was true of a number of perfectly good songs.

Speaker So you had to be ruthless with yourself in a way, you have to be you have to be honest with yourself and honest about the show and it paid off.

Speaker I mean, there was one show in particular that we all loved. We all loved called.

Speaker A.

Speaker When Messiah comes, it was a beautifully written song. The lyric was beautiful, and we tried it with a Tavia saying it, and this was at the point where they were being thrown out of the community, out of the you know, the community was being thrown out of the their homes. And we had the rap, I sing it heaviest sing, and it never worked, and we all realized that it was in totally the wrong mood, totally in the wrong.

Speaker We did have one a lighthearted, amusing song at that point. So it went.

Speaker Tell me about rehearsals. What was Jerry like Robin’s working on?

Speaker Well, Jerry, basically, I think Jerry’s bad, unless I’m mistaken. It’s been many years. I think Jerry spent in rehearsal much more time. And the dancing they did with the scenes he had and the system both and the system and his dancing around the system with the scenes and in general as the assistant set up the scenes and then Jenny came to Jerry, came to look at them and made suggested changes. And I worked mainly with the assistant when he was setting up the scenes and with Jerry when he came in to look at the scenes. But but I think he spent a good deal more time because it was much more complicated with the dancers.

Speaker What do you remember about him giving the cast certain kinds of exercises to do?

Speaker Oh, I think we started every morning with exercises. I think that’s done fairly frequently with music. I think he may have started it.

Speaker I don’t mean like physical exercises. I mean exercises in which they did certain kinds of, um, role playing having to do with prejudice.

Speaker And I remember now that I don’t remember any of the I like to think of.

Speaker OK, um, what can you tell me about you said he spent more time on the dancing, but you observed him directing actors. What can you tell me about how he directed actors.

Speaker Well, he as I say, he came in usually when the same was already on its feet and the actors who are already directing a certain way and he’d give small directions frequently, mainly about attitude, you know, you don’t like him that much or you’re trying to hide your love for her and the kind of thing that is very helpful and.

Speaker And he and he had a sense of what the what the actor needed to hear. He was not as great the director of of actors, I think, as he was a choreographer where he got. Astounding reactions, but but he but he had a sense of what we are trying to say and what he wanted said on the stage. So and he was able to communicate that to the actors. He usually, as I say, worked either through his assistant or through me with the actors except with with zero and probably with Maria, who played Golda where he spent much more time with them.

Speaker Somehow he got the singing and the dancing chorus, though, to become the people around it. How did he do that?

Speaker Well, then he emphasized constantly that they were not Broadway dancers. They were not. And I remember him saying, this is your Broadway dance. Stop it, you know? And somebody was what they want me to break a leg. You want me to chop some wood? What? You know, but he he he reveled in it. Moments of clumsiness, you know, following that from a dancer, a good dancer showing a bit like particularly in the in the in the wedding scene. So that should not look like a thoroughly organized saying until. The battle dance where the.

Speaker The boys who who, you know, the smart boys of the village knew how to do it.

Speaker Hi, how are you talked about this a little bit, but how did he behaved for the cast in general and how do you think the cast how do you think the cast felt about it?

Speaker Well, he was as I say, he was not a warm person and he did not have a very intimate relationship with the cast except maybe one or two people. And I say maybe somebody like Maria Candelabrum with whom it worked for a long time, but he didn’t have when there was a casual social gathering of the cast, particularly of Xeros there, he was never there.

Speaker And and there was never easy banter with him, never I would try to talk and maybe we had a couple of very casual little talk, but I would never try to be amusing to him because he was not.

Speaker Well, maybe, maybe because I can’t help it, sometimes I tried, but basically he was not that kind of person. He was. You know, a cold disciplinarian. I don’t think he thought of himself that way. But he just thought.

Speaker The the shows, the thing, while he was interested, is the show and what’s going to happen on stage and to repeat myself. This show meant so much to him, I thought now I guess I didn’t work on him on other shows. He may have felt that way about every show, but I don’t think so because his family was somewhere in the wings.

Speaker What is the significance of the central image of the Fittler and where did that come from?

Speaker You know, it’s hard for me to remember that, but I now I know that he planned to use.

Speaker The Fetlar to move us from scene to scene and.

Speaker As a result.

Speaker First of all, as a result, we had some fiddler top fiddle titles, the Fiddler story, Fiddler on the Roof, which we got from from the from The Seagull painting.

Speaker And of course, we have other titles like Tavia and the Old Country and Stefano’s.

Speaker And when we finally decided on Fiddler on the Roof.

Speaker He and then we wrote the opening monologue to justify the title, he used that fiddler to go from saying to CNN, we found increasingly it was boring. So little by little, he dropped the fiddler and we have him now like two of the most three times in the show and and he represented, you know, to to Jerry, I guess to us the the feeling of us, of this community, the tradition of this community, which goes on and on.

Speaker And even when we and even when we went to America, he had the fiddler going with them. Meaning that tradition will carry on. They will be synagogues in America, don’t worry about it, you know.

Speaker But there’s something I think there’s something more. About the symbol of the Fittler, isn’t there, Fiddler on the Roof is such a great title. It really resonates. Why is it appropriate for the show?

Speaker Well, actually, it was it was an accidental title. We never thought of having a Fiddler on the Roof. The dead come from The Seagull painting a. And originally, it came, I think, from Jerry’s concept of having the fiddler representing the feeling of the community, the traditional community, whatever, carrying guests from one scene to the other. And then we were once we were committed to that. Were you you know, we were looking for a title and the and the image of the Fiddler on the Roof was so intriguing. We just borrowed it from the painting.

Speaker What’s he doing on the roof?

Speaker Looking over what’s happening.

Speaker We don’t know, do you think it has anything to do with.

Speaker A kind of precariousness and yes, yes, yes, yes, because actually what I said, what the the monologue says, it sounds crazy, you know, but it sounds crazy, though. But in our life as a fiddler who lives a very dangerous life, we live a very dangerous life while we stay up there if it’s so dangerous, because that’s where we live. That’s our tradition. Yes, it does represent the entire.

Speaker That fiddler. By the way. The cello played, the fiddle was miserable because he thought they have wonderful part and they kept getting cut down the Taliban down and eventually thought, can I play another part in the audition? And we once did have another part for him and the vision.

Speaker A. There was a time when when they’re when we cut out that miserable ballet of the second act, Jerry wanted something to substitute for it.

Speaker He wanted another saw, another ballet. So I suggested I seen. In which people come from another shtetl, they were thrown out of this temple and they come through with figure. I had like to act, as, you know, two people and they say, what is this place? And they say this is even worse than where we came from and they leave and they are there and our people are very indignant, but, you know, we’re very proud of it. And they think about an attempt to live around which which we we subsidy cut that scene and that song.

Speaker But that song became the scene at the can talk about, if you would, Jerry’s use of the circle. The was a very strong image and fiddler all the way through, which actually changes, I think, you know, tough guy at the end. Do you know what I’m talking about?

Speaker Yeah, but the song at the very at the secretary level, the circle at the beginning with with the was the family holding together, everybody holding together, the mothers, the fathers, the sisters, the daughters and sons, all of the circle and and at the end he has them the circle and the circle breaks up. Now, that’s that’s his image in the last version. It was not used that second was used at the beginning for choreographic purposes, but at the end that when they leave, as you saw the last production at the at the in the last production, they just walk off in the background and the second is gone. But I think the second was a very vivid image in Jerry’s and Jerry’s mind.

Speaker You talk about how he used dance in the show and how what how Jerry used dance in the show, they didn’t stop and do a no no, not nothing in the dance.

Speaker And nothing in that show is just the dance. Nothing everything says something important about the story, even this dance. So we cut said something really important about the story. But we but there was something we knew, which is why where because the dance was about Tavia being miserable, that his daughter was marrying out of the faith and the people in the town laughing at them. And the fact that his daughter has been has as. Made a fool of them that way that we do that. We knew all of that had happened, that he was miserable, that and that it would not be accepted by the town. So they were dancing for 10 minutes, you know, and dancing it beautifully. And the show stopped that. So everything about every every dance was said, something that that moved the show along.

Speaker Tell me about Glock’s Santorum, who was he? What was his relationship to Jerry and what part did you play?

Speaker Say the clock was set? We had a very small part for the wrap up all the way around Glocks and a Glock.

Speaker Sandra Bullock said there was Jerry’s old dance teacher. And out of, I guess, out of for sentimental reasons, he gave them a part, they gave him the part of the rabbi, which was a very minor part. But since Golok said there was a dancer. He gave like a little dance in the middle of the wedding and. That’s an amusing little dance, which now we do in Australia and Japan and France, everywhere there’s a rabbi dance, his little Black Sabbath pants. But I think Jerry did it for some sentimental purposes, which is of the sweet.

Speaker How did that work out? How did they relate to each other in this different relationship?

Speaker Clark and Jerry Clark was very, very.

Speaker He listened to Jerry completely, I mean, Jerry was the boss by now. Look, as just a student of Jerry’s. And what bet was was certainly very gracious to them. He you know, he corrected him, but kindly so it was it was kind of kind of a nice thing for Jerry to have done.

Speaker It kind of irritated me a little because because I couldn’t read a line to kill him. So, you know, I gave him a few lines and he got the minimum value of it because he was really not an actor. So. It didn’t bother me very much, really, because it was very minor, somehow the show rose above it.

Speaker So survive the show survivors of how a Prince wrote that Robbins was indispensable to Fiddler. Do you agree or do not?

Speaker And I can’t think of any other director. They would have done that job. I think other directors could have done Fiddler together with a different show. And it might it might be just as successful in a different way, but not have been the show. This show me that I had had the Jerry Robbins stamp on it.

Speaker How would you define that?

Speaker Well, it is it is tough. It is mainly the Zionists mainly. That’s true. It it’s it hasn’t got a breath of that of the sentimentality of the Second Avenue, breast feeding, none of that. And, of course, to. None of it is in the script either. I mean, I hated that, I wanted to avoid that by all means. But Jerry knew how to put it on the stage with no sentimentality, no fake romance, no fake anything. And so it has his stamp.

Speaker And you are right, I want to hear what Jerry Jerry himself was that a useful man.

Speaker But Jerry.

Speaker Understood humor so that because I’m comfortable with humor, I was comfortable with him, I mean, he knew what he would know about what’s funny and what and what was true. I mean, there isn’t a joke in that one. Every every laugh comes out of character. And that’s the way I want to. That’s the way he wanted it. And he understood where the laughs were. It is not as true. The film. And so there’s another stage.

Speaker Could you speak about the importance of making the show universal, which I know was important to all of the collaborators which Jerry talked about? It’s not a Jewish family. It’s a family who happens to be Jewish. What how important was that? How did you achieve it in Jerry’s role in.

Speaker Well, I always thought I always described it to at the very beginning, I said it’s not about a Jewish family, it’s about a family who happens to be Jewish. You can’t write about an Italian family without it being Italian, but it’s the family. But it’s what’s true of all families. And the problems of the universality of it was much clearer to me after the show opened and after it went to the show to other countries when I went to Japan, which was the first foreign production, and I was very nervous about this very American show going to Japan, the first question the Japanese producer asked me is, do they understand the show in America? It’s so Japanese. And that’s when I I said to myself, this sure is universal. And I understood this. The struggle between parents and children. The the. The the. The children giving up the traditions of their parents and the parents fighting to hold on to them, the the conflict with the with the outside forces. In Japan, in Japan, it was the American conquerors, but it was all they sense, all of that was true of their experience. And and the whole feeling of immigration, of coming to the stranger in a strange land is true of every culture, every culture. And I must say, we didn’t think of it, that in writing it, we didn’t say, let’s make it universal. We wrote the story we wanted to write. And it had those elements buried within it and and those are the those are the elements that are now on the stage and thank God it works everywhere.

Speaker You said a little while ago that you read the original. Salaam aleikum stories in Yiddish. There’s not one Yiddish.

Speaker Well, I think there’s one word that is so important. The one with words like, why is it important that. Why is that important? Well, we didn’t want that. Actually, the people on that stage are talking Yiddish. That was their language and any.

Speaker Intrusion of a Yiddish word was would be strange. I mean, what what does that mean? When when they were saying, I love you, they were saying it in Yiddish and we made an absolute rule.

Speaker There would be no Yiddish word except the word Laham, which is a universal word, which is like, you know, which is a universal toast. So. And even that we translated to make sure that it was that it was clear that Lacayo meant to life so offensive that I had a lot of quibbles with Zero about their. Because zero would introduce Yiddish words for a laugh, and I would go back stage and say, y’know, if you say a thing like Takase, he says because did you hear that? Audience reaction. I said, I heard the audience reaction. I said, but this very cheap. I said, I’ve been avoiding it for years. And if you are. No, no. But what I was like, he would say, listen, when I’m on the stage, it’s between me and the audience. And you get out of the ordinary, everything gets out of the way. I said even the script. So I said, they’re not. I’m it makes no sense for you to use a Yiddish word like except. To get a fake laugh.

Speaker So, so.

Speaker Jerry wrote, I’m reading, I think it’s from his diary, Fiddler was a glory for my father, a celebration of and for him. Did he ever talk to you about his father?

Speaker No, he never spoke to me about his father specifically, but he did say that every once in a while he said, well, this is this is our tradition, too. You know, Joe, I said, of course.

Speaker And I knew that he was thinking about his father, his family, as I did to one of one of the things I regret most deeply was that my father was gone by the time for the rope. And I wish I didn’t read the stories. And yes, I heard them and hear this father read them to me. And my Yiddish even then was not very good. I mean, except. Except I could hear it well, but I couldn’t read it through. Well.

Speaker How important to the success of Finland do you think it was that all of the collaborators were Jewish?

Speaker Well, I can’t tell because we had nothing to talk to.

Speaker To measure to measure the ends, but.

Speaker My guess is that it wouldn’t have been the same show if the collaborator’s if any of the collaborators one that you wish.

Speaker Apparently, Jerry’s father came backstage on opening night and had a rather emotional moment. Were you around at all? What did you mean? I heard about it later. What did you hear about opening night?

Speaker I was busy on my own.

Speaker But what did you hear about?

Speaker Well, I heard that that his father came back and and in a kind of a way said. Kind of forgave him. So my my impression from that story was his father’s. Well, now you we understand each other. I don’t know what the difficulty was between him and his father and possibly the fact that he was gay.

Speaker And his father was a typical traditional Jew and I and the Gaynor’s had not been invented by the Jews. So.

Speaker Although I frankly, I wouldn’t be surprised if in the in the state there was a there were the usual number of gays, I’m sure, in the caves, they were using a number of gays in the caves.

Speaker That’s right.

Speaker I’m just going to ask you when you’re ready, you can put the drink down some more before you. No, that’s fine.

Speaker Tell me about the critical reception to the show. What was how long did it run and what was that like?

Speaker Well, the original, very original critical reception was in Detroit. There was a I did a newspaper strike and the only review we got people from Variety and there was a negative review.

Speaker I don’t remember exactly what it said, but it was something like, well, it’s another ordinary Joe Schmo Jewish show.

Speaker And I was I remember one of the other Jewish I was there and it was it was all altogether. Altogether.

Speaker Weekly negative. In other words, didn’t say Tahara, but they said just a routine, that kind of show and that kind, it was, of course, the depressing. But the audience after the first night, even the first night, reacted very differently, and I’m sure that the reviewers who because that critic was somebody who worked for Ford, you know, he was a stringer in Detroit. I think if the critics had been there, I think we would have gotten better. Not great, because we weren’t great yet. But it was. But. The first night. People came out. It’s a story I told before. I love this story because it’s absolutely true. I was standing in the lobby during intermission, very nervous, and a lady came running out. She ran to an open phone and the understanding of the additional. This, you’ll understand, she said, Harry, for one night, you should have given up, you get your gin game.

Speaker I tell you, it’s a very interesting show. You love it. You really would love it in Madrid. And they have a program.

Speaker And I burst out laughing and Hal said to me, what does that mean? I know per gram, but what does that mean? He said, I tell them in the middle of everything, they have a big role and she’s thrilled. So anyway, that was the first critical reaction I heard.

Speaker And I heard other people that that a it was a very Jewish audience. And I heard other people saying whether we like it or whether they like it.

Speaker I don’t know whether they like it, and the next night they came because it was a it was a benefit for the nuns, the Catholic benefit, and the reaction was exactly the same.

Speaker And they loved it. And then I felt even though we had a lot of problems, we had this endless. Ballet, we had some of the scenes were a little shaky, I, I personally felt they said we’ve got a good show. I didn’t know we’d have a giant hit. I felt we’ve been pretty. We’re pretty safe to stop you for a second.

Speaker Peter, are we really OK?

Speaker We are. But, yeah, there’s a ringing phone on the other side of this wall. Adam Hold on, Abwehr.

Speaker And then, of course, I know what admitting Drinan was, I thought, oh, my God, you’re going to tell me the whole story. Yes, yes.

Speaker No, but thank you for letting you know until I translate for how that for you. Oh, thank you.

Speaker On his behalf, um, Sheldon told me that, um, he was once in the house. And a woman afterwards said to him, What is love? I mean, he said, are you OK? Yes, yes, yes. OK, so tell me how long the show ran and why were I think.

Speaker Well. Well, the the actually, the New York critics were all good.

Speaker Some of them were great and some of them were not very good. I mean, they were all none of them were bad, but one Walter Kyra, who was highly respected. I remember a phrase where he said.

Speaker Something like this.

Speaker It gets to much regards to Broadway. And not enough to have a target. And I resented that because we worked so hard to make it pure and. I was wondering how would he make it even more Broadway by by putting it in a field somewhere, you know, I mean it in the field anyway. But the was that it was not a a rave by any means from well to Kyra. It was from others. The Times was very good at that time. It was the Herald Tribune which was what to cover. How long the run, I think around either eight or nine years, and that at the time it was the longest running Broadway musical overtaken by the by the British.

Speaker OK, so how many Tonys did the show win and tell me what you remember about Tony nine.

Speaker I believe we won nine Tonys. I think everyone connected with the show that Tony and I don’t remember what I said in my little speech. I thanked my father for introducing me to show of their stories. And I think that’s as far as I went, and I remember that there was a little boy that he wasn’t mentioned by me. I said what you had he won that he won the Tony. You could say that you are true self. So why do I have to praise him?

Speaker Well, it’s kind of curious. Seven people in addition to Jerry, one Tonys that night for Fiddler Jerry one two. So seven other people, including you, won Tonys. But from what I understand, not one of you acknowledged Jerry. OK, a few of you could have forgotten, but seven, what was that about?

Speaker I don’t think it was deliberate. I really thought, at least as far as I am concerned, I know that if I won a Tony, I would talk about where the inspiration came from. And I wouldn’t give the the routine thanking everybody in the show, you know, thanking Jerry and Zero and Marie and the wonderful company and the people who shined my shoes. You know, I didn’t want to go into that.

Speaker So I know that my father was not a deliberate, deliberate intention to try to get his work, because I was very aware, as I have said all along, that I thought that he was he did a brilliant job, you know, and, you know, despite the fact that he had certain. Personality problems with which we had that we all had to deal and which is OK, which I gather was true of his whole career, and it was it’s interesting, too, that he never did another musical after Fiddler. And I think and I’m sure he was offered every single musical that ever was. I think it’s because. Fiddler represented the best he could do. He felt that he could never top Fittler as a piece of creative art and also as a personal statement. And I and this does not come from any conversation I had with Jerry because we never talked about it, but I know that even I approach him once for another musical and he expressed an interest and then backed away. But I think that that that fiddler was the apex of his career as a as a musical director.

Speaker What did you learn from him?

Speaker It’s hard to put into words, but I know that I like a great deal about from him.

Speaker I would put it in terms of discipline, in terms of making being very clear about the focus of your show, of being very self-critical about the work you are doing so that you don’t do things that please you but do not. But to to do not serve the show, things of that sort, which are very. Very much part of Jerry. Jerry Robbins and I like to believe it was also part of me, but it was very clear with Jerry.

Speaker He directed a number of performers in their signature roles, Brennaman, King and I, Mirman and Gypsy Martin and Peter Pan, you know, Streisand and Funny Girl. Do you think that was casting genius or was it his brilliance as a director? Which.

Speaker Well, I think it’s the latter.

Speaker I mean, if you could relate it to zero, for example.

Speaker Well, zero, I think. I think was a very obvious piece of casting. I mean, if you think of the people who were there at the time, zero had just come out of a funny thing. He was not only funny, he had done James Joyce. He had done Ulysses nightgown. He was a brilliant actor with not with extraordinary instincts. He understood this media very well. I mean, he was raised in the same tradition as I was. And and he had all of the assets, all of the attributes, so that he was a natural. And we all went for the idea of zero very early. There were others who, particularly Jack felt Jack Gilford comes to mind. And I remember Jack’s audition, which was also very good. But Jack had a kind of a. Humbleness or modesty? That was not quite right for the part, and I saw it and obviously Jerry so and so.

Speaker Well, Jerry was, I think, a very good cast, at least in terms of this experience, and I assume it was true of his other shows, too, but of course, he always cast stars as much as he could. Which is, you know, with which is. You know, which is very safe and but the guest stars out there who could do it not only because they were stars.

Speaker Why wasn’t he asked to work on the movie version of Fiddler?

Speaker I think he was deeply disappointed that he was not asked. I think it’s because the producers felt.

Speaker It was not.

Speaker He couldn’t adjust to movie making. He was too expensive item in his salary. I mean, he would. Rehearsed forever, he would shoot forever. And it’s probably true, I think he had one experience with West Side Story when he when he shot at the opening of West Side Story, and it took a brilliant, brilliant piece of film. But I think it took forever. And he was fired from just from West Side Story for that reason. So. So they didn’t want to take a chance. I. I was sorry, I think I think he would have made a better picture. I mean, I like the picture very much, but I think it could have used Jerry Jerry’s touch. I mean, they made decisions that I could not control like that they did not want to consider zero. Because they felt he was not filmi, that he was. I think the phrase they used as he was too big for the film, he overwhelmed the screen. Now, I’m not that familiar with screenwriting, with you know, I’ve only done three screenplays, so. No, actually, two, and they were both my they both based on my work, so I had no way of judging, but so I had to take their word for it. Zero was prepared to audition for it and they wouldn’t audition them. I said we’re not going to use him. So we don’t want to insult him by auditioning him and turning him down. But that was the reason that they felt there was another secondary reason. I think they came to see him under the knife when he was playing for laughs. I think that was also true, although I assured him that, but he was right, there was nobody right.

Speaker Steve Sondheim said that Jerry Robbins was the best stage of usable he’d ever seen. Is that true for you or not? And why?

Speaker Well, in my experience, it was I mean, for Fiddler, it was just incorporate that phrase. Well, and in my experience, Jerry Robbins was best states of musicals I’ve ever dealt with. There may be others just as good live, but in my experience, it was Jerry Robbins.

Speaker You also worked to know how with those well, Agnese, I worked with Agnese only as a choreographer, rather direct, and of course, I worked recently with the director. I had have enormous respect for.

Speaker David Livi Laveau, who has stated quite differently but could very, very effectively so I don’t want to in any way. Countries them they both work differently, but they were equally devoted to the material and equally successful.

Speaker Would you say that, uh, Jerry Robbins was a decisive worker or an indecisive worker and some examples?

Speaker Um.

Speaker Hey, Jerry Roberts was. Frequently indecisive in the sense that he would try things. Different ways. He didn’t come to an audition, it was a staging of a scene knowing exactly what he was going to do. He tried various different possibilities. He would use the actors as his tools, and we’ve asked him to do things. You know, differently take different kinds of chances so that I don’t know whether the right way there’s indecisive or experimental, but he certainly didn’t come to a rehearsal knowing what the final product would be before he started.

Speaker Would you say he was a secure or insecure person and how did that manifest itself?

Speaker Well, I think he was both really. I think he knew that he was very, very talented. I think he knew that that he was I had the gift of genius. He was also insecure because he wasn’t sure. And at any moment that this what he was doing was exactly right. I gave you the illustration. I mentioned the illustration of when he said battered people’s. People will ask, where is the Robbins Ballet in the second act? And I said, I don’t think anybody is going to answer there. He thought that he would be judged. All the time, and that says to me a sign of insecurity.

Speaker Where would you sort of place him in the pantheon of American musical theater talents?

Speaker Oh, here’s where on top he is certainly one of the very best, if not the best. There are there are very few there’s a there’s Bob Farse who’s very different from Jerry Robbins.

Speaker Is your job, it is totally different from Jerry Robbins, although they work together and I think David Laveau is a very, very talented.

Speaker Director.

Speaker But but Jerry is right up there among the very, very best and always will be.

Speaker The Times said that he was the most important innovator in the history of the American Museum.

Speaker That’s true in his time. He absolutely was. Absolutely he. He was the one who decided that the story. Was the thing and all of the dancers, all of the signs of all of the book, all of it had to serve what the story was telling and.

Speaker That became. Slogan of this whole.

Speaker And there was a giant step forward for the American musical.

Speaker Is there anything that you would like to say about Jerry that I have?

Speaker I don’t think so. I think you know, I think it’s just. If you have what is the word for this to be dry, you want to look at your piece, OK?

Speaker I’m sure it’s it’s all been covered. It’s all been covered. All right. Let me just say focus was about.

Speaker Disintegrating parents held company so special feeling for the show, it was not just another musical, it’s his people, as my people perceive an insecure ego. Where is the second act? Robbinsville Ballet phone call after the opening. I mentioned that.

Speaker Yes, I put the paper down for. OK, tell me about the phone call.

Speaker Well, I think that you told me about the phone call.

Speaker He called you?

Speaker Yeah, he called me right after the thing and said it’s like a religious experience and have all that.

Speaker Well, yeah.

Speaker Hard task. Master perfectionist. He played favorites from Rick and it would be hard to read myself professional, basically unfriendly. I was an intermediary. I loved working with him. I said I loved working with him.

Speaker You can say it again.

Speaker Is his devotion to the material he wanted seems constantly rewritten, usually or frequently went back to the original several of them.

Speaker Did he tell me how you like working with him?

Speaker Actually, I really I really loved working with Jerry Robbins because I knew that I was working with the best. I know his standards were high. I knew I had to reach those standards who worked with him. And it was not only a challenge, but there was a. Glorious challenge. It was a. It was a credit to the to the craft to work with him, and it’s an experience I will always. Sabr, be very proud of you and I am sorry for people who never work. Jerry Robbins.