Interviewer: I’d like to take you back to the kind of the early to mid sixties period when my angel of death and kind of come to New York. But just give us a little sense of the flavor of the scene in those times, because there was so much cultural and literary theater arts work just exploding in Greenwich Village and all over New York. Give us a little sense of what it was like for you to be here in that period in the mid to late Sixties.

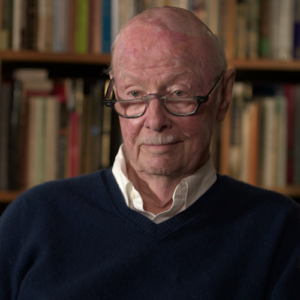

Jules Feiffer: Well, I’m not sure anybody was conscious, deliberately conscious of the activity. Mostly, it seems to me you were conscious of all the forces that worked against such activities because particularly little generations and young people today who are used to seeing anything and doing anything and getting away with anything. The period of 50 years, even before Joe McCarthy, we had the House un-American Activities Committee loyalty, those teachers getting fired, post office workers going for a long period of repression. And when people simply weren’t speaking up and were afraid that liberals, young, educated liberals didn’t know they had First Amendment rights and were very cautious of what they had to say. And in the middle of that, this arts revolution was slowly happening underground and abroad. There was Samuel Beckett and Ionesco, and over here there was Edward Albee and Jack Gilbert Gelber, originally from Chicago. Well, Interconnection and Living Theater and I mean, stuff was just beginning to work and beginning to happen. And of course, the emerging civil rights movement and the sit ins and all of that. So these two things were happening at the same time. And if you were simply around and young and active or had an interest in this stuff, you just went with the flow.

Interviewer: It’s great. Excellent. How did you know James Bond? How did you meet James Baldwin and what was he like in those days?

Jules Feiffer: Well, if you were again, if you were around at that time and connected, as I was, to the Village Voice, which was partly founded by Norman Mailer, you just met people and I forget how I met you may well have been at The Voice or might have been a George Plimpton who had these literary parties. He was the founding editor of The Paris Review, and he just about everybody and anybody but Baldwin. And I’d love to talk and shoot on those off and say things to each other. And we also had a mild passion for drinking. So we closed a few bars and got a lot of work done. And it was a lot of fun. I mean, it was fascinating because when you first met him, the first impression was that he was ugly, physically ugly with these big fog locked doors. And then he talks for 30 seconds and he becomes the most beautiful person you’ve ever seen. I mean, you not he’s not trying to do anything. He’s just talking. He’s not trying to charm you. He’s just having a conversation. And he had great conversations. And it was whether he was saying little or nothing, the literary stuff or, you know, about race, whatever it was. He was absolutely captivating and fascinating. And on a very conversational level, there was no sense of self-importance.

Interviewer: And of course, you alluded to it. There was a tremendous amount of work being done in the civil rights movement at that time. And New York was it was certainly an important part of that. You had a lot of figures here, Bayard Rustin, people like that were working here. Just give us a little sense of that as well. Well.

Jules Feiffer: Part of that I got out of the Army in 1953, and I had two passions. One was to make it as a cartoonist, as a satirical cartoonist, and the other was to meet girls. And there was a group, a pacifist group called the Fellowship of Reconciliation that was having a meeting on civil rights. And there’s 53, I think it was. And somebody named Bayard Rustin was speaking who I’d never heard of. And I didn’t think it could be that interesting because I was a white liberal. I knew all about civil rights. And he proceeded to give a talk about what was important in America. And it wasn’t the Cold War and it wasn’t repression, it was race, and that it was not an issue for blacks. What he was. He used the word Negro always. It wasn’t an issue for Negroes. It was an issue for the whole country. Because until we solved the racial issue, there was not going to be anything happening in America that was that was going to be significant or worth paying attention to. But in something like a minute and a half, he shifted my entire sensibility about what I thought in terms of something I thought I knew something about. And it basically became the bedrock of how I looked on the movement when it got full sway and civil rights then. And it shapes my views today. I mean, there’s basically the way I look at what goes on in this country, whether it’s an education, whether it’s all issues, is as a student of Bayard Rustin.

Interviewer: That’s fascinating. That was one moment that had such an impact. When did you first did you did you had you heard of Maya Angelou before she came over to your place and involvement.

Jules Feiffer: Or did you know it? I heard of Maya. Only Harry Belafonte was having a fundraising party for Dr. King. This is when he was raising money for the for the poverty marches and trying to raise money, you know, and and so he had all of these people from the civil rights movement, Fred Shuttlesworth, Andrew Young. I heard Andrew Young speak and I was blown away by I’d never heard of them. And it was immense. And anyhow, we’re in this room. Baldwin was there, and Jimmy always traveled with the retinue, five or six people, the brother David and several others. And there was this tall, imposing young black woman who was just amazing. And she didn’t know anybody and looked uncertain. And she started know she started talking to my my first wife and then wife, Judy and me. We started talking about her, but we just got along. And I think she told us she had she was a Catholic. She had been a Catholic, Dunham dancer and was not in New York for very long at that point. And and we loved our stories. And she we just had a good time. We invited her. We lived not that far from her. He was at that time on 75th and Weston, and we had an appointment at 1819 Riverside and she came to dinner.

Interviewer: So take us again. From what I understand, a few weeks after Dr. King had been assassinated, James Baldwin went over to my house. She was very distraught by because she was about ready to go to work for him, actually for King. And he was he was saying, let’s I’m going to get you out of the doldrums. I’m in. I’m going to take you over to Jules Feiffer and Judy Feiffer’s house. And, you know, we’re going to we’re going to, you know, just tell stories and get get you out of your melancholy. Well, that’s how that’s how we’ve heard it so.

Jules Feiffer: Well, you know, it’s interesting. And you’re talking to a man five years short of 90. So what do I know? And it’s not how I remember it, but. But it may well be true.

Interviewer: Well, tell us what she was. Do you remember anything she was any of the stories?

Jules Feiffer: Well, no, I don’t. But I do remember that she was absolutely captivating and she just told these stories in a very matter of fact. There was nothing show Wolfie about it and there was nothing, you know, the way at parties of people who want to take over the room and control the room have a way of asserting themselves. There was none of that. It was just her just being a little surprised that we found that interesting and telling more and we just pulled it out of her because it was I mean, I would ask questions, I would laugh uproariously and Judy would ask questions, and she just spoke. And it was a delight and just a thrilling evening. And then she told us she was writing stories. And when we read some of the stories, she loved to show it to us. And they were fiction. And that was a real letdown because the fiction was not nearly on the level of the story she was telling. And my wife Judy, who at times played a kind of founder, and she she connected talent one time. She she she was the one who spun who discovered Mommie Dearest and made it into a book and and into a movie. She said to just add that my I’ve read these stories. And when she did, Judy, who was a friend of Bob Loomis at Random House, took the stories to Bob Loomis. And there we are. This the rest of it. She became, you know, from a dancer to this world. Renowned poet and writer and I suppose elder stateswoman. You know, it’s remarkable. And she never changed. She was still this very light spirit.

Interviewer: That’s great. That’s great. And do you remember anything she was talking about growing up in Stamps, Arkansas, in the midst of, you know, really oppressive poverty and just brutal segregation? Did that does that jar your memory?

Jules Feiffer: No, I don’t have a memory to jar you. But it’s I mean, that that’s the story. If you came from that generation and you were black and you came from the South, that’s the story. That’s I mean, that that it was not uncommon. And what was uncommon was her way of telling it, her zest for telling it and and the spirit.

Interviewer: And Judy must have seen something or heard something in those stories that made her want to contact.

Jules Feiffer: Well well, by that time, I had written stories. I had written some of these stories and showed it to both of us. And and Judy had these connections. I mean, I knew Bob Loomis, but the idea of calling him up and doing this sort of thing would never have occurred to me. But it occurred to Judy and she she took the stories over to them and he read them and was blown away, of course. And that’s what began it all. And my over the years, I would run into her and she would stop me. And she said, I will never forget what Judy Phifer did for me. And not a big deal. But just it was a big deal to me because that after long, you know, winning every prize you can think of and we will celebrated and canonized just about. She still stayed with that that very beginning.

Interviewer: I just want to go back to one other thing before this. Can you give us a little sense of the time that Martin Luther King was assassinated, how people here in New York reacted? What was the just the sense of things when you heard the news and how people were affected and how devastating it was? Gives us a little sense of it.

Jules Feiffer: Well, it was 1968 and. There was King and there was Bobby Kennedy. And there was I mean, it just seemed and three years, five years earlier, there was JFK. It seemed to be a period of absolute insanity. And in a sense that. A commentary on America as a whole and what the country had become was in danger of becoming. And where the hell we were headed at the same time that Vietnam was heating up and had heated up. And all of this was in one part of the Vietnam War and its intense, needless and insane escalation. And what that said about us as a people, these acts of unbelievable violence and unprecedented in terms of the importance of the people killed and how easy it seemed to be to shoot them. I mean, it seemed that all you had to do was buy a gun, close your eyes, and shoot it at any figure of importance. And whether his name was Kennedy or King or Lenin or whoever, you got them. And and so one felt helpless about the times, helpless about your country, and in a dither about our future. Because you knew you couldn’t let this lie. This was something had to be done.

Interviewer: When when I know Why the Caged Bird Sings was first published, what was your reaction? Did you have a chance to read the book? I mean, what was your reaction to that book?

Jules Feiffer: Well, it I felt pleased and proud and excited. And, you know, and then you look this cartoon balloon of images and who knew, you know, out of this casualness, out of nothing, uh, this woman who was who I thought was a dancer is a brilliant writer. And she was just beginning, of course.

Interviewer: What did you think of the book yourself?

Jules Feiffer: Oh, I thought it was a lovely piece of work. A lovely. But what a piece of work and magical.

Interviewer: Do you think it was? It strikes me as being a little bit different from a traditional memoir or autobiography, the sense that it had a lyrical, poetic feel to it. Can you talk about that at all? Does it strike.

Jules Feiffer: You? No. But it was if you met my new mother, she too was different. She was not like anybody else. And an approach was not like anybody else. And what she did, and it’s not easy, was find a way of replicating who and what she was on paper. And a lot of writers can’t do that as a creative voice, which may have not a hell of a lot to do with who they were and what they are. They’d be effective, but it may not be them. It’s a.

Interviewer: Great book. What was unique about my Angela in Your Pen was most unique qualities about her, do you think?

Jules Feiffer: Oh, just what I said. I mean, just that it’s both complex and and straightforward at the same time.

Interviewer: Do you think she’s had an impact, though, in terms of you know, a lot of women have said, especially African-American women, who said until her books came out, they didn’t really have a voice like that that they could relate to?

Jules Feiffer: Well, you know, there are certain figures, male and female, that represent transitional figures. There are people who are artists who give you permission to think in certain ways you hadn’t thought of before or to create in certain ways. You know, you you you read something. You say, What? No, I could do that. I think I can do that. I think I can try that. But up until that moment, it never occurred to you that you could do this. And Maya will have been one of those people who gave other writers permission.

Interviewer: So, Jules, by knowing Maya at that time, there are certain things that I’ve learned about her personality. One is she says it like this. She says, I would be of use, but I won’t be used. And she has an air of sometimes commanding in the room gently or stating her place. And every once in a while, a little bit of temper or attitude or something flares up out of her passion. Do you ever recall seeing that?

Jules Feiffer: No, I don’t. But, you know, she was a very imposing, beautiful woman, you know, And the term used to be statuesque, you know, And but with all of that, instead of being intimidating, she was embracing. I mean, she had enormous warmth and feeling and. And wanted to be part of what made things work, what made things better, and also what explained things she communicated. Her job was to tell you a story and tell you a story about herself because she connected to so many things that in the past and in the present were important to know. And she was as much as anything else, a storyteller.

Interviewer: It’s kind of interesting because sometimes when you are that thing, so naturally you’re doing that and you don’t even know you’re doing it. But I see what you’re saying about that passion that she had to want to be a part of things. A lot of people remember her work, whether it’s a point or whether it’s a book, as you say. And it it gives them permission to be different or to accept themselves in a different way. Prior to her coming to New York, she was just beginning to make friends across color lines. Did she ever tell you anything that you can recall intimate about that whole race issue of embracing city, you and your wife at the time?

Jules Feiffer: I don’t remember. Or she may have. I just, you know, can’t recall conversations like that. But it’s, I think, more important, the time she came out of which is the time we all came out of of a certain age, there was everybody knew anybody with any politics that was to any degree on the left knew that things were happening and things were beginning. And there was a kind of underground excitement and pleasure in it because the with all of the things that went wrong with all of the injustices, with all of that, all of us still at that time believed in America and believed in the future of this country and believed, too, that things were going to work. That things, you know, that one had to do this and one had to do that. But in the end and how tough the struggle was, but that it was all going to work. I don’t sense that in today’s world, but that’s maybe that’s my fogy ism now and I hope I’m wrong. But at that time you felt the possibilities were exciting and limitless and mine was part of that time was part of that excitement, was part of that movement. And a number of us were were felt. We were.