Speaker Well.

Speaker We’re talking late 60s and we’re talking about the period after I had essentially left the movement.

Speaker I was in the process of leading the movement.

Speaker And so that part of what’s going on at that time is, is I don’t have a place anymore. The movement had been had been a place of expression for me and a place of expressing both anger and caring about the country. And that as the movement began to turn both more anti white men, I won’t dignify and call it nationalistic. It was really anti white. You can be you can be nationalistic without being against people racially. So as the movement began to turn more anti white and also use the rhetoric of violence more, I really felt myself in a position of beginning to speak out against that. And so that began.

Speaker So therefore, I was beginning to to criticize people with whom I’d worked.

Speaker People whom I cared about. People whom I loved.

Speaker And so that was that was hard to do, and I felt that I had to do it.

Speaker I guess both for myself. And then also there was a period that I went through that I was me. This was coming into which was a period when I did not know who I was writing for because I felt that what I was writing was so out of sync with what people were listening to and wanted to hear. And so there was a period that I went through which I which I said to myself consciously that I’m writing for people who were not yet born because I don’t want somebody 50 years from now to look back at the record and say, why didn’t somebody say these things?

Speaker And so at least take a look back and could look at my work and say, at least one person said these things.

Speaker And so that this was, you know, I mean, I was trying to to to to walk a line between a black role nitro.

Speaker And so I’m certainly you know, I’m the one black on the air personality at VHI at this time. And so I want my radio show to be a avenue for black people to be able to express themselves without censorship and all that.

Speaker But at the same time, I found out of the position where I get used by people to say things which I don’t agree with. And then I get implicated in it because of how I see myself as being.

Speaker This simply this that this conduit for for for black expression. And so I’m trying to to to to mediate these two worlds that are increasingly tearing at each other. And I don’t want to have to choose one or the other.

Speaker I don’t see why I should have to choose one or the other. And so that’s you know, that’s all that’s going on here.

Speaker And yet very little of that. Some of it, if I look at it carefully. Contradiction and complexity is in the playfulness of those pictures. What do you think?

Speaker You just look at the pictures in relation to that very difficult journey you were taking.

Speaker Well, I don’t. I don’t. I don’t know that I know that I have an answer to that.

Speaker I think partly it may be a matter of.

Speaker I’ve always been a very religious person, not in a conventional sense, but certainly religious in the sense of.

Speaker Always asking consciously, what?

Speaker What is it that God wants of me in this situation and trying to ascertain what that is? And that if I have a sense that that I’m doing what God wants me to do. Then it’s a lot easier to get through whatever the consequence of that is. At least I have a sense of that. I’m doing what I’m doing when I’m on this earth to do. And if people don’t understand that. That that’s not. Then maybe they’ll understand it later. Maybe they’ll never understand it. But what is what is important is that is that I that I know this is what God wants me to do. I may not understand it, but I. But if I have that sense that that is one thing to be doing, then it’s OK. It’s OK. Doesn’t mean it’s less. It means that it’s easy.

Speaker It’s not easy. But.

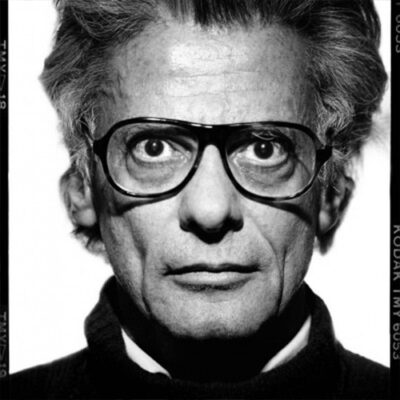

Speaker OK, so this Kovacic pictures, again, that might allow for the playful equanimity, you put that into a sentence because my voice will be completely taken out.

Speaker Yeah, well, I think, you know, if I if I look at a you know, look at a look at a picture like this and, you know, I’m looking, you know, right there down the barrel of the lens, you know, and and and my feeling is it’s just one of.

Speaker Whatever it is, it’s OK. And I’ll be able to deal with it.

Speaker And so it’s a confidence that comes out of that.

Speaker That spiritual journeying and struggling and.

Speaker And at least wanting to to to align myself with what I’ve what I feel is. My partner in the divine order.

Speaker And so bad. Yeah, it’s OK. It’s all right. That made that picture I like.

Speaker Let’s talk a little about the 60s are both the pictures that you’ve seen of the X and now of the X about the 60s and your.

Speaker In your own memories of that period as a photographer, as a participant, as a critic.

Speaker When you say those two dicks images of the 60s, what he calls the.

Speaker They are emblematic for you today. Talk to a 60s because 60s, if you remember, as a photographer, as a participant, as a critic of that period.

Speaker I probably could talk about that better if we had some specific photographs to talk about.

Speaker Let’s talk about the snake. Was it.

Speaker I guess there’s so many emotions that that fight with within within me when I think about what I think about the 60s. I don’t. Have nostalgia for the 60s. I don’t miss the 60s. I have said more than once that if the 60s came back, I would be a policeman next time around. Which people seldom hear the humor in. But I mean that humorously. But people sometimes get upset when I say that.

Speaker So that so that when I think about I mean, when I look at Dick’s photographs, it’s looking at the 60s in a different way because we’re looking at the 60s, not through event as much as it is through the faces of some of the people who made the period.

Speaker And that’s a very different way of being. I have to confront myself and all of my memories and emotions. And so so, for example, George Wallace and the photograph of of George Wallace with the attendant. And the first time I saw that, I audibly gasped. I just gaf because. All of the evil that that man represented, I thought was in that face. And and it’s like George Wallace got shot. And so since then, there’s been this kind of softening and this reservoir of feeling and the man’s paralyzed. He doesn’t have power anymore than any other. But then, you know, when I think back about the fact that he was running for president and he was really a a precursor of a lot of the conservatism, radical conservatism that we’re seeing in the country now. And the man did not stand for good. He did not represent the good. And we forget their.

Speaker And so that when I saw that photograph, all those emotions about him.

Speaker And I was glad I was glad they came back. I was glad I was reminded. And I was glad to recognize that. No, I do not forgive you.

Speaker You know, and yes, you’ve been in that wheelchair for, you know, over 30 or over 20 years now, what have you.

Speaker But I do not forgive you that you were you did act you did do some very evil things.

Speaker And so, so, so, so looking at the 60 through his photographs is really a confrontation with myself in a confrontation with my own memories.

Speaker I, I teach a course on the 60s and you know that I don’t get, you know, 500 plus students in the course. But it’s like teaching I’m no medical history in a way. If my students were to look at that photograph of George Wallace, they don’t have the history with him. They don’t have the emotions they don’t have. They may have some information, but they don’t have the experience, the relationship with him.

Speaker And so that’s why the photographs from me, ah ah ah, confrontation with myself.

Speaker The one of of of Julian and I was very struck by the weird shape. I was struck by Julian, looks like a preppy and Julian’s always had that look, you know. But he’s he’s dressed like he’s you know, he’s a young teacher at a prep school. And then right behind him is Bob Zellner.

Speaker And I think that was daddy married. I think next to him.

Speaker And so knowing Julian and, you know, I met Bob Zellner in.

Speaker Kind of 1960, me, Bob’s father was a Klansman. Used to be a Klansman. And Bob decided he’s from Alabama, right. From Alabama.

Speaker And he decided that he would, you know, go the opposite way and very, very fine person. So they’re behind him. And then there’s this. This is which. And so that.

Speaker One of the things that I think we cultivated in the early years of the movement was to look as presentable and respectable as possible.

Speaker And, you know, it was a tactic that worked. And so there’s Julian, who represents that very soft, you know.

Speaker And then there are these two nice, ordinary looking white people. But then it kind of fades into nobody else’s distinct in the photograph. As one black guy to Julian’s left to somewhat. But everybody else kind of fades.

Speaker And so it’s like there’s this this is wedge of history that’s coming.

Speaker But exactly what it’s going to be as the wage comes further and further. It’s not clear it’s going to be. And so that’s both a known and unknown quality there, which certainly I would not have thought about the early years in that way without seeing that voting. It certainly caused me to to rethink. That, yeah, we thought we knew what we were doing, but we knew only went so far and that we were young. And so we didn’t know that. You do one thing and you think you’re gonna get this result.

Speaker And actually, you’d get some result. You could not have anticipated this than the other. And so there’s this black mask behind them that.

Speaker It’s not clear.

Speaker So it’s a it’s a.

Speaker Looking back, it’s a disturbing photograph for me in that scene and especially, you know, I would never have thought of us as being a wage. Just, you know, and you have all kinds of association to wages because, I mean, the police would go on demonstrators on a wage in Chicago. They did that in 68. And so, you know, that that’s a formation that a military formation wage. And so Japanese policemen use that demonstration. So it’s it’s a mixed. It’s a mixed.

Speaker We get a lot of mixed emotions, mixed emotions from the.

Speaker This is the first photograph of Jerome Smith and somebody else to two young black men. That’s that’s a right on Poterba.

Speaker And once again, you know, there’s. There’s something about his photographs. That.

Speaker Well, it’s like anything in terms of art, but the more you bring to it, the more it opens up. And so if you know who Jerome Smith is, then you see there’s a difference between the two black men you’re on.

Speaker Smith was a freedom rider who was beaten very, very severely.

Speaker And that there is the famous meeting with Bobby Kennedy, with Baldwin and Lena Horne and Jimmy Baldwin was there and some other people.

Speaker And Jerome Smith was there. And your own Smiths, the one who made a statement to the attorney general, something to the effect that if he was drafted to fight against Cuba, something that is a fact, that he would not do it. And Bobby Kennedy got livid and essentially the meeting ended because he considered that so unpatriotic. And John Smith broke down crying for Bobby Kennedy. Didn’t know what you wrote Smith had been through. Just ride on the bus without being hassle. You know, when you think about the movement, you know, I think sometimes this was so ridiculous. But what were we what was this all about? What did people die for? People died for the most ordinary thing, which is to be able to move in public and be left alone.

Speaker You shouldn’t have to die. You shouldn’t have to get beat up with an inch of your life like your own did or something like that. How stupid. Now, the term I don’t know where where he was coming from. So when I look at those two photographs, there’s a difference in how Jerome is looking. It’s a slight difference, but it’s there in his eyes. And the other one?

Speaker You know, it’s very you know, I’m sort of very straightforward photograph.

Speaker You know, um.

Speaker Liana Perez was, you know, Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, and he was like the lord of it, I mean, it was one of the worst places in the south.

Speaker And the.

Speaker The picture of him. It’s like it’s like one of the things that I see that I feel that Dick is trying to do in his photographs is to get behind the the that we all wear and just catches and our humanity. And I think that with Leander Perez of the mask and the humanity or one.

Speaker And he may look like the stereotype of the pot belly, you know, evil, white, southern or, you know, southern sheriff.

Speaker What have you. But I think that that was the man also.

Speaker It’s a picture that gives one the shivers that one can even let somebody who is not an actor could look that way, that no one who is only an actor, you’re able to do that. And then, you know, it’s not real anymore that somebody should do that. And it’s real.

Speaker That’s pretty terrifying. That’s pretty terrifying.

Speaker And I think that’s that’s not untypical.

Speaker And I think that’s what the history made of a certain number of.

Speaker Lee Leander Perez was there, the whole Perez, the press family at that time were their political bosses of this parish, Plaquemines Parish, in Louisiana, and conditions there were very oppressive for black people. I mean, it was really.

Speaker It’s not rhetoric to say that the South, before the civil rights movement, was a fascistic state.

Speaker And what I mean by that is not only in Louisiana but certainly in other parts of the south. If you were black and you subscribed, say, to Ebony magazine and the postman decided you shouldn’t read Ebony magazine, you never got the magazine. And so in terms of just the information you were able to receive was controlled by people who were not acting in your interests.

Speaker And so he was just, you know, one of the most brutal of of the sheriffs that was, you know, that know that existed at that time. Yeah, oh, yeah, yeah. I certainly I think anybody would say this is not somebody they would want to hold for Thanksgiving or encounter, you know, on a dark road at night.

Speaker Malcolm X. That is.

Speaker I have puzzled over this photograph because it’s so contrary to what he does and finally everything else. I can’t think of any other photograph in which. The other photographs draw you in in some way.

Speaker And there’s something about this one that pushes out from me.

Speaker Generally, when I think of Malcolm X, you know, I think of seeing, you know, the strong jaw, you know, the eyes and what have you and all, it’s blurred here. And I guess I have two responses to it. One is, is that. He’s white. The lighting makes him white. And Malcolm was, you know, light skinned and the other is, is that. It’s a hip. It’s like he becomes a mask, his face is mask like. And I don’t mean that mask y in terms of hiding something, but mask like in the sense of an African mask. It’s almost like the photograph is not Malcolm X, the individual. But Malcolm X is icon.

Speaker Certainly, you know, the facial features, the nose and the lips are very pronounced on the moulding of the face there.

Speaker And for some reason it it reminds me. Of Dick Self, self-portrait of of. Holding the cut out, there is a cut out of Jimmy Baldwin’s face and he’s cut it out in such a way that half of Jimmy’s face fits over his face. And that photograph of knock on reminds me of that because of the the lighting, because of, you know, it’s both white and black. And because I feel that what Dick is doing in the in the other photograph is almost.

Speaker Talking about a commonness.

Speaker Um, in terms of humanity, of blending or melding, and so I’ll see the same thing in the end in the Malcolm X photograph.

Speaker I have no idea how he did it or why he did it that way. But it’s not an individual shark. What trache like you have a Wallace and Perez and you know so many of the other figures from the 60s.

Speaker I like it because it’s.

Speaker It makes Malcolm unfamiliar. And I think that’s what I like about a lot of Dick’s work, is that something which I think I know is suddenly unfamiliar. And so I have to relate to it rather than relate to my image of it. And so that’s certainly true with with with now, and that’s not Spike Lee’s Malcolm, that’s not any Malcolm I received or experience.

Speaker The photograph of the mission council evokes. Feelings of just real disgust, just real disgust. My first response to it, and I apologize for the advance of. Is it just a feeling of being sick, a white man? And I guess what I what I mean by that is, is a certain kind of white male smugness. That has just been so destructive and so many lives.

Speaker And so I think in that photograph, you know, there is when you see it like that, they all look, you know, rather pathetic. And it’s like, my God, that all those people die because of these men wanted to establish their egos.

Speaker And so it just. It’s.

Speaker It certainly demystifies the halls of power.

Speaker That these were the powerful. And look at them.

Speaker So it’s a great photograph. It’s really a great way. It should be, you know, in classrooms to study just so that we will not get caught up in the mystique these people try to weave.

Speaker The photograph of the of the, uh, Andy Warhol factory.

Speaker Leaves me somewhat, totally bewildered. I just honestly.

Speaker Do not understand them. Do you not understand?

Speaker What it is they thought they were doing. Do not understand who they thought they were. And so I look at it and I’m just I’m bewildered. The only response I have is bewilderment. I don’t want to know them in any kind of way.

Speaker And so I’m just I’m bewildered by them.

Speaker The priesthood is not the 60s that you participate.

Speaker No, I don’t either. I don’t think that I don’t.

Speaker When I think of the 60s, I don’t think of them when I think of the 60s.

Speaker When I think of the 60s, I think about.

Speaker The incredible. Idealism that it’s in their early 60s was certainly a time. When we believed. That ideals could be made concrete and we try to do that. In our lives and in society.

Speaker I think the effort was a success. People talk about the 60s were a failure and this, that and the other for that brief period in time, a period of time from 1960 to 65 at the most. But for that brief period of time.

Speaker People really did try to care about each other and care for each other.

Speaker And certainly I think that from many of us who were a part of that.

Speaker It has informed our entire lives.

Speaker And it’s a part still of the things that we try to do and we try to bring that kind of energy to whatever we may be involved in. And most of the people I know are are still involved in some way of of working with people, trying to bring people together. However, however, however, they can do that. And so when I think about the factory.

Speaker It’s just not you know, even when I think about the Yepez who come in in the late 60s, the hippie movement and then the hippies and I’m talking about Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin and Paul Krassner and, you know, all those people still that, you know, with those people that was still.

Speaker There was a quest for values.

Speaker And values that would make this so.

Speaker And, you know, I’ve certainly never felt that about the factory.

Speaker You know, I live the Hotel Chelsea for a while in the late in the early 70s, I guess it was. People live there. I liked her. Always something about her that we liked and respected.

Speaker The rest of the picture, the Chicago Seven. I found. Really? Really interesting. I knew four of them, five of them, I guess.

Speaker I was very taken with with the photograph of Abby, I guess, of all of them, I was probably closest to Abby. And it was very, very hurt by his suicide.

Speaker And that Dick was able to get heavy when he wasn’t on one.

Speaker And that’s Avi in that photograph.

Speaker You know, soft, quiet. When I first met Abby was before he was Abbie Hoffman, he was very quiet, very quiet, very straight person goes back to. First met him in sixty six.

Speaker I guess it was sixty five years.

Speaker I went in there and, you know, before he started doing acid and going through a transformation of very quiet, very sweet person. And that’s the quality that comes through his. It’s kind of down in the photograph, as I recall.

Speaker But yet there the energy, you know, from him. He’s not making contact with the camera.

Speaker And for Abby to not make do with the camera, that’s quite unusual, you know.

Speaker And so I have that picture of him when he wasn’t being Abbie Hoffman, just being himself. You know, they’re both himself, but being himself in and decide that people didn’t see.

Speaker You know, it’s just very moving. And then and then there’s Jerry and that. And that is just the photograph captures Jerry because Jerry had this quality of.

Speaker It’s gonna be a good Jewish boy who wants approval, and I see that in the photograph.

Speaker And I don’t mean that in any way, you know, derogatorily toward toward Jerry. But just just descriptively, I think it’s one of the things that that makes Jerry lovable. But that quality, that quality is there.

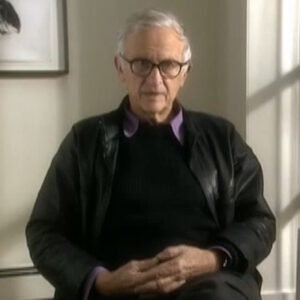

Speaker And the surprising ones for me are the ones of Tom Hayton and Dave Dellinger.

Speaker Because.

Speaker You know, these were, you know, two of the main architects of the protest movement against the war in Vietnam. And as I recall the photograph, Tom has no cloth belt or rope belt or something on and is looking, you know, fairly disheveled. And David looks like a middle aged man, you know, kind of slumping in his body, you know.

Speaker And what have you.

Speaker There they are there. Their ordinariness. And I would I would think. That one of the things that that the young people, not the students I teach, you know, they have these romantic notions of the 60s. And I try to express to them.

Speaker The 60s were made by ordinary people.

Speaker They were made by people just like you who were sitting in a classroom and decided that they didn’t like what their government was doing and they want to do something. And so you see that with with David and with and with Tom and those photographs, especially David, you know, just your average middle class man. But he was animated by a sense of values, a sense of caring. And so he did something.

Speaker But let’s not forget sight of the fact that, you know, he’s a father. He’s a grandfather. You know.

Speaker And so you whoever you are looking at this picture, you share this with him, too.

Speaker And so perhaps your soul can be animated. To do something also. Oh, really? Oh, I like that. I like that one.

Speaker Not the idealism that you’re talking.

Speaker Well.

Speaker I guess the image that’s coming to mind is Jerome Smith again.

Speaker And I guess. I guess. And. The image of Jerome. I guess I would extend that image.

Speaker Of the hurt and the beginnings of anger. That’s their.

Speaker And I would extend that image until it became frozen in anger.

Speaker And really captured my anger. I mean, it’s almost like. Oh, yeah.

Speaker Anger, I think anger as a force which which which can take one over. Just as. You know, in the photographs of Dick’s father, you see death as a force taking him over. And so that to me, that’s part of what happened, that that that anger just came and.

Speaker And captured people.

Speaker And so that that I think it’s it would be I think that certainly.

Speaker There would be the equivalent on the movement side of the photograph of Lee and Perez. I think there’s a black counterpart to that, which hurts me to say, but I think that that’s also objective, objective truth.

Speaker That part of what happened was that people fell in love with their anger and fell in love with their hatred and. And really, a lot of them have not gone beyond that. So I do still captured.

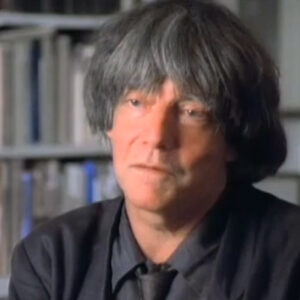

Speaker So that would that would be the photograph. I mean, I uh huh. What happens? I mean, the image that comes to mind is the photograph of Al Sharpton. And the Al Sharpton photograph is, you know, once again, I don’t know of any other photograph quite like that, the montage kind of effect on. I interviewed Al Sharpton on Baier when he was 14 years old.

Speaker Probably the first time he appeared on the radio. He was a boy minister and he called me up and wanted to talk about the. There was a nursery school teacher strike and all that.

Speaker And my impression of him at that time was that he was certainly the youngest. I am also adroit Musselwhite ever met. And so I think the photograph just really captures the what I would call the do do the duplicitous quality that are we dealing with a carnival man here.

Speaker And that’s almost disparaging carnival. I don’t want to disparage carnivals in any way.

Speaker Somebody who’s very slippery, can’t get a fix on. Can’t get a clear view of somebody who’s playing a shell game, a political shell game.

Speaker And somebody who simply is not to be trusted. And so that certainly captures, I think, one, you know, the shadows out of the 60s, one image of the shadows of the 60s you see in there because there’s nothing to hold on to.

Speaker With real.

Speaker The flimflam game. Then there are the rings. You know, the chains and what have you, that dazzling, you know. And so it’s it’s a.

Speaker The movement in that photograph. It’s no place for the eye to set on.

Speaker And I think that’s part of wood shopping done.

Speaker It was an inevitability about that.

Speaker I didn’t know that. Yeah, yeah.

Speaker I guess I have a couple of responses.

Speaker I think that after the assassination of Dr. King, it was inevitable.

Speaker I think. The assassination of Dr. King left people with the feeling, well, if you if you destroy the best that we have to offer.

Speaker Then why should we care?

Speaker So I think that that’s actually the watershed. But it starts the chain starts before that. The chain starts before.

Speaker I think that for it not to have happened.

Speaker People would have had to learn to live, caring attention and ambiguity and making that a way of life. What I mean by that is. We were able to do it for a short period of time, which is that you do not do to others what they have done to you. And you don’t do that because you care about you. So.

Speaker And so what that what that.

Speaker Confronts you with then? Is that even as you are angry at and wary of white society in general?

Speaker At the same time.

Speaker You treat every individual white person as an individual. And you regard each one as a person and not as this category. That means living with the tension.

Speaker I don’t know whether it’s fair to ask people to carry that tension. But that was what was asked of us historically and, um, for whatever reasons. Uh. Boy, I mean, I remember when I moved to New York in sixty one, I live in Harlem and I used to go down to 25th and some of the avenue in the evenings and there were the street corner speakers and.

Speaker I mean, was that attractive? You know, it was all the white man’s fault.

Speaker And, you know, I just come up from the south, you know, and I, you know, come up, you know, I’ll stop going on this other than the other. And it was so attractive that would just solve it all to have a racial world view.

Speaker And so I had to consciously resist that. It was very seductive. I mean, there he has a charisma that goodness doesn’t.

Speaker And so it would mean living with living with attention and.

Speaker People chose not to do that. And when you choose not to do that, then.

Speaker Hatred, Swamiji, the anger swallows you and you become its puppet. You become an archetype almost. So I don’t know whether it was an.

Speaker Yeah, I don’t know whether I would use lightness as the word to describe.

Speaker The.

Speaker And I guess I would shy away from that word because.

Speaker Of a number of people. Who followed him, who listened to you?

Speaker So I don’t know what.

Speaker I think in the photograph, the photograph almost has a kaleidoscopic effect to it.

Speaker And, you know, in a kaleidoscope, you know, the patterns are always shifting. Things are always things are moving around and creating, you know, creating new patterns, new colors. What have you. And yet it’s still contained. And I feel that in in terms of that photograph of.

Speaker Well, I guess. I guess.

Speaker Mm hmm. I guess.

Speaker He is a vessel for people’s projections.

Speaker And so perhaps the word that I would use is emptiness. And so that whatever you want to project into him within certain parameters, you can do so and elastic.

Speaker Because there’s really nothing there. So the flash.

Speaker And so it’s really I mean, you know, you think about Dr. King and then there’s Al Sharpton and you have to wonder, why is all this happening within my one lifetime? You know, this should happen over several people’s lifestyles. Not one my lifetime. How do I put these two things together? And, you know, it’s like he’s a caricature.

Speaker But then when I say he’s a caricature, I really worry that I am.

Speaker Not respecting. The pain of all those people who need him.

Speaker And so if. He’s the only one who’s going to attempt to address them.

Speaker Then I can’t blame them for listening to him. I’m going to him because nobody else will speak to them.

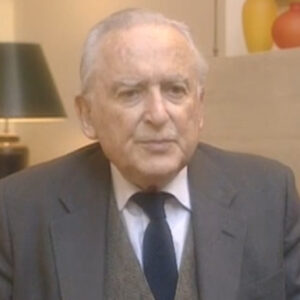

Speaker Certainly one level in the photographs is, you know, you see the progression of death taking taking this human being and you experience death as this.

Speaker This force is impersonal force. This thing that just slowly is taking. Taking whatever life is away, and so in the last photographs, you know, you can you can see the skull and and even the teeth are like teeth are in skull.

Speaker And then there is the the amazing encounter of, oh, this man staring directly into the lens and.

Speaker So he’s starring at me. And so when I look at him, I think of I think of my father, I envy I envy the photographs that he was my father died suddenly.

Speaker And both my parents died suddenly. And so I envy him that he was able to have the dying.

Speaker And I wished that for myself that I’m not be deprived of the dying and so that.

Speaker So that when I look at it, you know, I certainly think of my own parents. But I think especially of me.

Speaker And will I be able to stare somebody directly in the eye? I’ll be able to stare my son in the eye. One of my sons in the ah, the way the way the two of them.

Speaker There’s something frightening about it. There’s something.

Speaker Heartbreaking about it.

Speaker And in the father’s face, you see the bewilderment, the helplessness.

Speaker The pain, the fear.

Speaker I’m you know, I’m really kind of awed that Dick was able to.

Speaker To do that.

Speaker With his own bomb, it’s much easier to chat with somebody you know. You go to a hospital and want to photograph, people are dying, you know, that’s different. But this is this is this is as my son refers to me. This is your progenitor.

Speaker And to be able to do that.

Speaker And to not blink. And, um.

Speaker You know, it’s like death is the great teacher, you know?

Speaker I mean, it’s the great teacher because.

Speaker We’re all so close.

Speaker And I look at that photograph and I see his skull. And then I wonder, what if we went around and we’re related to each other as if we were all skulls, that we’re all going to die. And whenever we die, it’s going to be to some.

Speaker Everything else is irrelevant. Race, religion, gender. All the squabbles we get into is irrelevant to the fact that in the end we all look alike skulls. And so that’s that’s what I’ve lived with.

Speaker You know?

Speaker And I’ve been thinking recently about the need. I mean, that’s extraordinary, Jacob. Israel is extraordinary name. You know, generally Jews have either one or the other of the names, but they have both of the things. I don’t know how you acquired both of the names, but you know, Jacob, you know, the son of Isaac who wrestles with God and then his name is Change and he becomes Israel.

Speaker But here this man is Jacob. He’s both.

Speaker I’ll know what to do with that. But I’m just I’m really struck by his name because it certainly carries, you know, all of Jewish history, you know, in his name.

Speaker And so on the one hand, it’s Richard Amidon’s father.

Speaker On the other hand, it’s this man who went to life as Jacob.

Speaker I have no work to go beyond that.

Speaker I’m looking, you know, living with that photograph. It’s certainly one is brought in two. One is brought into the sanctuary of something holy.

Speaker And the photograph was a blessing. It’s a robust.

Speaker You know, you’ve seen.

Speaker Yeah, well, I spent the civil rights movement. I mean, you know, part of it, I was the singer in front of another photographer. And the period I was a photographer, the not one of the happiest years of my life because I could feel like it was able to do with see.

Speaker And it was wonderful to be an instrument of scene.

Speaker Um, and so, you know, I’d photograph people and, you know, their their homes and Mississippi, their shacks and, you know, plantations and, you know, and also and, you know, demonstrations and the beatings and some of the brutality and this that and the other. Um, and certainly, you know, some things of some things of our um. I don’t. Part of what is how powerful about the photograph? Well, let me back up and say this. I was aware that when I was photographing the what I was photographing was a relationship. It’s my relationship to whatever is being photographed. So it’s not the object. It’s the relationship photo for photographs or relational. The power of the relationship between father and son in the photographs of Jacob is real. Taken by his son.

Speaker It’s certainly beyond anything that.

Speaker That I experienced as a photographer.

Speaker And I don’t know whether it’s relationship.

Speaker It’s certainly the relationship of father to son, son to father. It’s also a relationship of of son to death.

Speaker And son to death of his father. And so I think that’s also why I would I would say that the photograph invites us into the sanctuary. It’s about as close as one can come to the experience of death in someone who is still alive.

Speaker I mean, there’s also the photograph of which I assume is a photograph of him after he died lying down.

Speaker I think it looks like he’s dead. But he may be sleeping. He looks like he’s dead. But the similarity between it and the photograph of when he’s still alive, you know, is the almost identical.

Speaker And so the photograph is a blessing.

Speaker And the deep is the deepest. And and the, uh, in Hebrew, the, uh, the root of the word that we translate as blessed means to build the knee and adoration. And so and so I really mean that in the deep is in the Hebraic sense of the original sense of. Of my experience of that photograph. It’s a true blessing.

Speaker Say that again. Did I say that that sounds good. What? What the hell did I mean?

Speaker Well.

Speaker Photography, a photograph is a relationship when somebody writes a review of of my book. It is some time a matter of chagrinned to me that the ordinary reader of the review who has not read my book will not be able to see how much of this review was the reviewer and how much is talking about how much is talking about me.

Speaker I guess I thought with Avalon’s photographs that he doesn’t pretend to objectivity. He doesn’t pretend that he’s not photographing a relationship.

Speaker So his his point of view is there, but it’s not intrusive. And so there’s this strange mixture of of.

Speaker This is how I feel about it. But this is what’s there also.

Speaker And so that so that I’m I’m allowed my experience of it.

Speaker And that my experience is often very complex. And so that I don’t come away from the photographs with a feeling morally self-righteous.

Speaker And I think certainly if we take the photographs of the architects of the Vietnam War, I would have been so easy to do that in such a way that one would feel morally superior, morally superior.

Speaker I can’t come away feeling morally superior, coming away with my emotions of disgust about them. But I also come away with a little question mark about me.

Speaker And so that so that my expenses of his photograph is that they trust me back to me and to my humanity and my choices, and what kind of choices would I have made, what kind of choices to make?

Speaker What kind of choices will I make? And in the long run, you might so much better.

Speaker I mean, I can’t be too sure. I’m so much better than they are. And I think that one of the things that we’re afflicted with is, um, is moral self-righteousness. I mean, everybody, you know, I mean, the the the race to be the victim of the month.

Speaker You know, and if I’m a victim, then I’m more righteous than somebody else. And that kind of hypocrisy is photograph something like.

Speaker And so that’s that’s why they’re there. They can be a searing experience. I mean, it’s to go through these photographs. It’s just can be searing experience that you can’t get away from yourself. And so that level of honesty we don’t see represented in art that much.

Speaker No visual or the one.

Speaker Even the military celebrates the theatricality of so many masks.

Speaker Face to face is a window to the soul. You’re absolutely sure. How you respond to that in the face of what it is?

Speaker Well, I think certainly the. A question that has gone through my life has been. It’s been I guess I worry about it sometimes in terms of.

Speaker The kind of face my life will make, you know, because because I do believe that that the life is seen, that life is seen in the face. And so I guess that’s one reason why I am so drawn to his work, because so much of the focus is on is on the face.

Speaker And no one sees the blemishes and warts and the wrinkles and, you know, this, that and the other and. The unguarded moments, the moments when you know that that little incident when we just let all the guys drop.

Speaker That’s what it catches.

Speaker And it’s not that the mass are not a truth. They are true. But this other is a truthful answer.

Speaker And it’s perhaps the truth that we don’t want to see ourselves. We certainly not want others to see. But it’s like looking at somebody you love in their sleep and they don’t have to hold their face. And somehow their facial expressions is really pretty ugly. And what have you. And this is the person whom you love. And what have you. And here they are, totally unguarded. Why people don’t like to be looked at when they’re asleep. They have a control over, you know, they can’t manipulate you. And so I love his photographs because they they get beyond that point where the person’s in control and gets that instrument.

Speaker Some person not in control.

Speaker And there’s another true review. I don’t believe unkind. I don’t feel a little harsh.

Speaker Oh, you even feel that the people are ugly.

Speaker It’s my face to.

Speaker And so if I’m afraid to look at my face, then I don’t want him showing me these faces.

Speaker And so, uh.

Speaker Yeah. I mean, I guess the only question that he comes out of. The Western humanist tradition, I mean, certainly. You know what, another century. Probably would have been doing etchings. He would have been door.

Speaker Ah, you know, Rembrandt and doing etchings and, you know, and that kind of thing. You know, fortunately, he’s in the 20th century now, the camera. And so he can do a lot more than make it do with it. But that’s the tradition that I see him coming out of and extending it, you know, certainly.

Speaker I think that the obligation of the artist period slash the intellectual is to the truth.

Speaker Period.

Speaker No obligation to the SIDOR whatsoever.

Speaker The obligation is to portray as well as one can.

Speaker The truth. To the extent that one is able to proceed. There’s no other obligation.

Speaker Anything less than that is believed to betray oneself as an artist, an intellectual.