Interviewer: I want to take you back in time to the early sixties when you were in New York. There was a lot of energy. There was a lot of artistic energy happening. There was some great talent, especially African-American acting talent. And you all kind of coalesced around a number of projects. First of all, just give me a little sense of what New York was like in the very early sixties for you and for the others.

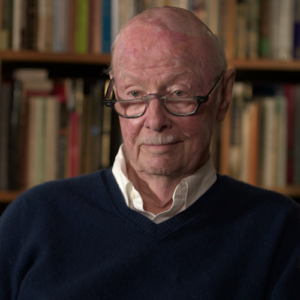

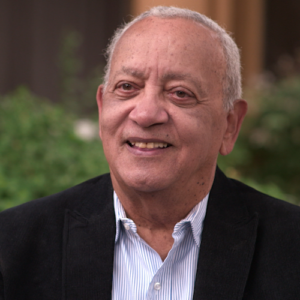

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Well, New York City was really in transition. It was the birth of the hippies and the anti-war statements. And I played a little guitar down in the coffee shops and read the hootenanny. And then the British took over all the theaters on Broadway. There was My Fair Lady. There was Hamlet. There’s a separate tables. They took over 99% of theaters and off-Broadway, began with the Edward Albee’s and the owners were Couch and Carol BURNETT was and Once Upon a Mattress and there was The Fantasticks. And we got together in 1960 at Second Avenue and Eighth Street, and we did a Jimi’s production of called The Negroes, The Blacks. And in that cast was rascally Brown James Earl Jones. Godfrey Cambridge. Charles Gordon. Lex Munson. J. Flash Reilly, Abbey Lincoln, Cicely Tyson, and, of course, Maya Angelou. So we got together to do that blacks, and it lasted five and a half years. So we kind of made an indelible impression upon the world public by doing judging these the blacks at the St Mark’s Playhouse on Second Avenue and Eighth Street and off-Broadway has never been the same. That’s where when we finished and the Negro sample took over the same building. That’s when I first met Maya Angelou. MOCKETT and her influence from then on has been indelible. She, with this, had this African influence because of her husband at the time he came of gone, I believe. And she had this her natural. And she was an angry black woman, you know, but so intelligent. And it’s infused the reason when the blacks was there and she played the white queen and Roxie Roker, who from from The Jeffersons. And we did that for five and a half years. The understudies with people like Billy Dee Williams and people like that. It was our home. We’d go and do some jobs and come back. And we we knew all the plays I played Newport News, the so-called connection to the outside world. And so spending five and a half years with Maya Angelou was incredibly entertaining, educated. And there’s a lot of love that happened with all of us. Godfrey Cambridge. Roscoe, how brilliant you were. And we held the audience hostage. That’s what it was about. There was a play within a play, and it’s indelible in my life, especially the performance that Maya gave on a daily basis with her and Roxie mostly playing these these these characters, the white queen and the black queen. Wow. Or before the written thing and went from there.

Interviewer: Why was the blacks so popular? Because in a way, you would look at it and go, How could this play have been popular? It was a it was a play about racism and about race. And it was very upfront.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: It was a play whose time had come. It was a statement whose time had come. It was. It was the Malcolm X time. It was also the Dr. King time. And then we had sensitive audiences who loved it and came back. Jane Fonda came back about 100 times. And we had some very diplomats come from around the world to see it. And it was so riveting because of what it was, was a secret ritual so that we got this audience and held them captive where we told them how. Story so eloquently written by John Johnny and the one man had a heart attack. Another woman screamed and fainted because the the the play within a plane was so riveting. And some nights it was just absolutely electric. And when it was over, they realized it was just a play in which sometimes there was no applause. But they were so impressed with what we did. But that was a play whose time had come. And it gave birth to a lot of other things. Oh, now you can say that. So let’s go with James Baldwin now and let’s go through a well known Raisin in the Sun, which came from Raisin in the Sun to that. And then all of a sudden plays like it and statements like it from all ethnic groups start to hit the boards and then movies started to come. Leroy Jones, Amar, Ras Baraka. And all of a sudden they had a voice, music and a voice. It was time as a renaissance time for all factions, not just the African-American faction, but the the anti-war faction, the folk music, the Bob Dylan era, the Jimi Hendrix era, the Edward Albee, all those. We kind of got together and created this renaissance of art that was necessary at the time we broke the mold, and it’s nice to be part of that, of breaking the mold. The mold has been broken quite a few times since then too.

Interviewer: Can you summarize very short just what the blacks what you said was a play with them? A player who was also referred to as a clown show is a subtitle or something. So what was just so we understand what it was just very briefly.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Well, when we have the audience and there was a little subterfuge in the in the ushers and the instruments, and they were put into this ambiance even before the play started, that they’ve got to lock the doors. And we started with Lucky the Doors and the secrets. And and then finally we started with a waltz mocking them. And then all of a sudden rascally Brown was saying, Ladies and gentlemen, and in focus, go, Ha ha ha ha. Then that started the whole thing and people just would work. What kind of player we come to see here? But it riveted Paris, so we had to do it in New York City. But it was still today one of the most complete experiences and timely experiences that I’ve ever participated with, that those people. People come back again and again and again and again. It was incredible moments, incredible moments.

Interviewer: In my have played the white which.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: The white queen.

Interviewer: Or white queen of scores is me. Tell me a little bit about that, her role.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: And what she was, the combination and jazz. And they wrote it a combination of every thing, the Queen Elizabeth, all the royalty, the white female royalty of Europe all these centuries and centuries of of have amounted to my mind, royalty when I say goes and all that stuff. And then it was the black kings. Queens said, Oh, it was so beautifully written between Roxie Roker and Maya and how the how the director made a dance out of it. So it was like a cockfight, but a poetic cockfight. And then Cicely Tyson playing the young black lady. And she she would mock. And if one of her lines was, Oh, I am the lily white queen of the West. Only centuries and centuries of breeding can dance can make me. And I have it. And she’s walking up this catafalque. And it was as a derision, but a very poetic, poetic derision, and raised the consciousness of race to such an element that it’s called the theater of the absurd. Racism is absurd. And that’s what it was about. It’s an absurd it’s it’s really absurd today. Absolutely absurd. And back in the sixties my into that and so that everybody in that cast the absurdity of us being separate for any reason.

Interviewer: Did you have any stories of my at that time? Obviously, you must have spent a lot of time hanging out with her as well.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Oh, yeah. Hanging out with Mya, who was at the time as this young actor. You know, I’d done A Raisin in the Sun, and I had started at the age of 17, and I had that kind of a. I call them a milkshake kind of life. You know, I didn’t have any consciousness and racial consciousness or anything. I was very fortunate to get all this work. So that deep, abiding culture, Maya was responsible for teaching me why I should be upset, why I should know more about my roots, a way to behave in a certain way. And it spread her her influence spread into the jazz musicians and the young people at the time. It was the afros, the dashikis. And I eavesdropped a lot, and I set that around her to listen to her and her contemporaries. And I saw her with the with Malcolm X from time to time and people like that. And I listened and listened and listened and planted those seeds back away. Never forgot what she said, but she was like that really much more angry, much more angry at the injustice. And that kind of mellowed out. And then she kind of grew. And with her influence, she became a poet and she became smoother. But the philosophy remained the same. So she’s probably the most indelible influence other than my great grandmother. She carries this message and now, of course, it’s indelible.

Interviewer: That’s great. Did you have a she put on as I recall, she put on a concert, a fundraiser for Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. And there around that time with I think Roscoe Lee Brown was, you know, partners with her. And they raised a bunch of money for Dr. King and for his organ. Do you have a memory of that?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Yeah, I was there as an intern. Well, there you go. She she her anger mellowed into something that was positive and positive influence. And the most positive influence, even today, is Dr. King’s legacy. And so she joined the good guys, if you want to call it. She was one of the good guys and people joined her because of that reason. Her probably influence saved a lot of lives who were angry and wanted to write and throw things and storefronts. And and even when Dr. King died, there was a deep breath and there’s anger. But she said it’s a it’s a bigger picture. I heard that same thing from Nelson Mandela when I was in South Africa. If anybody had a reason to be really upset that this injustice, it had to be him after 27 years and it came out of Robert Taylor with a smile on his face. It’s the same spirit. And Maya gives us, especially the young people. And that’s the legacy, which is why she became the poet laureate. There’s a bigger picture that we need to pay attention to. So she came from that angry young lady with the afro and the dashiki to the pulpit. She learned certain lessons and got some stuff, but she’d been at it every day until then. And she taught a great deal of people that there is a bigger picture here. That’s the most important thing, which is why she became poet laureate.

Interviewer: Do you think using art in this case theater blacks or her writing or acting you’ve done is a way of expressing that kind of anger and getting it out on the table? Yes, but in a more, so to speak, palatable way. Yeah. AUDIENCE Can you what if you could talk about that? If Maya used that technique.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: She and Maya, Roscoe Lee Brown, Godfrey, Cambridge, myself and others, we had a way of inventing some of that stuff on a stage in a film theater, and it kind of routes. The whole thing kind of gave us an exorcism. So we could get to the next level, get to the truth. And those of us who are fortunate to be alive still today for some wonderful reason, do have to carry that message. Continuing on to the young, because the young have not been taught properly and she was one of our master teachers. So now we have to get back to those thrilling days of yesteryear, if you want to call it that. We were responsible for one another and we teach one another certain ages, certain things to do at certain ages. And she did that to the to the nth degree. She was a teacher from the time she was born until the time she died. So her lessons and her memories will continue. You know, it’s she’s one of those lights.

Interviewer: One of the thing about the blacks, as I recall from her book, and I think she actually talked to us about in her interview that Max Roach had originally been assigned to write the music for the blacks. Absolutely right. But then something happened. He was upset about I’m not sure what happened, but maybe you could tell us the story that my in Abbey Lincoln ended up writing im. I wasn’t really a songwriter, say, but maybe if you remember.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Max Roach was was hired to put the music to the blacks. His wife, Abbey Lincoln was the original and the original production, and it was something they didn’t want to listen to. Our director, Gene Frankel, he didn’t have respect because he was a black patriot, a black nationalist, Max was, and very virulent with it. So they had this misunderstanding. So Abbey and Maya took it over, calm the waters, and Max kind of receded. But he really did a little the writing, very simple thing, you know, the the the. No, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no. The low, the no tears and dreams will come for me. That’s Max wrote that and Abbey wrote that, and they kind of smoothed it out. It was a very nice, haunting music that we sang. It’s indelible. Five and a half years.

Interviewer: Do you think it was I mean, just the idea that Maya would have stepped in and tried to do something that she really wasn’t even schooled in? You know, she’s, you know, say about her her spirit.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: And her spirit and she’s a peacemaker. She needs to get the bigger statement, the bigger picture, get this production on. Let’s not stop with let’s not do this. Particularly importance of this production in lieu of a black nationalist thing. This is a bigger picture, much more indelible than anything that Max or even Abbey was thinking of. They were too angry and could do anything artistic. If you’re not angry right now, you’re going to smooth it out and get the get the statement out there artistically.

Interviewer: You also obviously knew Louis Markey. Can you talk about the relationship between Dr. Angelou and her and who. I’m not sure they ever actually got married, but they were together. They were to capital. So what was he like or what was what was their relationship like?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Well, it’s it’s kind of probably it makes sense that she was pursuing her African roots and she’s she attended the United Nations and they met and they were attracted philosophically. I’m sorry. Yes.

Interviewer: I need to have was mocking that answer.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: So we got you.

Interviewer: Get I’m saying to him because there’s no narrator.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: In this. I got you. I got you. Okay. So when Maya met Louis Monkey at the United Nations, an attraction ensued because Maya was searching desperately for her African roots upon whose shoulders she stood. And I knew that. So it was a poetic meeting for her to meet the voice and the marriage. And then the relationship began. And it was a love hate relationship because he, you know, she she was an independent woman and he’s African and no one’s going to be than me, you know. So they did that thing. That’s that was a prediction of other relationships between black men and black women is still kind of ensued sometimes the day until they make peace about it. But Maya and vous was a love hate beautiful a love hate relationship, but a reestablishment of the African and American black roots. And that was symbolic. And she took it from there.

Interviewer: And that set her off on an unexpected, you know, discovery where she moved to Africa with him, of course. And they broke up. And I mean, it introduced her to a whole nother chapter in her life. Amazing. Yeah. You know, and if you had been in contact with her a little bit when she had had moved to Africa with him.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: But, you know, I got some some letters. I wish I could find them. I’ve got some left. Some stuff went out. But I got letters about her discovery of having been in Ghana and places like that and what you learned about the culture. And she studied about the Ashanti Empire. But what she rejected was her American female black independence. She was not going to be sickened or subservient to any male. And there was a little conflict there, natural conflict. So we’re coming to the to a today. Trying to make peace with that conflict today. But that comes from back there when amended one thing and the women did others. And it was a conflict that that’s where it was. You do what I tell you to do, and I’m not going to do that. I have my own, you know, So it was a natural conflict. She needed to be with him for that moment to get back to Africa, to learn what you learned to continue on. I think that was a prediction, maybe guide, if you want to call it that. She didn’t have that experience, so she took it and benefited. We all benefited from that experience.

Interviewer: One thing that tormented her, I think a little bit was that she was gone a lot when her son was was of age. And, you know, raising her son was difficult because she was always, you know, moving from one show to another, Porgy and Bess and the blacks and this and that. Did she ever talk to you? I mean, what do you think about that with your.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Mother and the difficulty with raising children and being famous and heeding a call for anyone, especially those of us, the minority? There’s always going to be some error, some mistakes. Somebody is going to need something to infuse the roots to your children and then go away. And so it’s not a continuum. It’s going to have its effects. So there’s the need for society to know these lessons, which seems to be a bigger need. And then the children do suffer because they don’t get their hands on one on one the way we started in the first place, where each age had a certain thing to do and they passed the message on from one generation to the next. And each age there was something to do. So in trying to do that to those two things, there’s attrition and attrition with not being effective to a lot of young people and not her son and had something that happens to me sometimes. It’s a difficult process to to be of service to many. When the people that are your blood think they suffer and it happens quite frequently, even today, it’s just the dues that we have to pay. And then maybe one day we go full circle and then they understand the whole thing because once we leave the planet, God forbid, they say, well, you know, she was on my side after all. But it takes that process, too, for the young people to understand there wasn’t personal.

Interviewer: Hmm. You know, did you her book her first book came out, I think, in 1969. Caged bird. Yeah. I wonder if you had read it at the time or what? Did you come across it? Or you have memories of.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: My memories of Caged Bird. I was on a run and I was on a short business run. I had stopped being so Afrocentric and sensitive at the time, so I didn’t read Caged Bird until two years later when I got a quiet time and took a vacation and realized I should have read it two years before that. But I read it and I read it again. And and since then, everything she’s written and said, I follow.

Interviewer: Just what were your thoughts of that book when you first read it?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: It’s the first eloquent statement about us as a people, about the people who are enslaved in any kind of form, especially women. There has to be some kind of expression that she successfully expresses love and writing and poetry to continue the legacy of maybe a Langston Hughes or or some of her predecessors to getting that frustration out. So I can understand viscerally what we were going through. The case of Bird Sings, because the only expression of freedom that can have is a deeper thought process. And in the vocal, every time I read, it evokes another emotion. And she got free. The cage door opened. By understanding her writing that book. So sometimes there is a subtle change in us as a people that she recommended very quietly and very gently. Sometimes the caged bird is comfortable inside that cage, so even if the door swings open, we don’t go out because it’s more comfortable in there. So maybe we should free ourselves sometimes. It’s like when the African-Americans were freed and there was a reconstruction still more comfortable to stay in a plantation mentality. And we’re still struggling with that. But she went to the point of saying sometimes slavery and encouragement happens personally. You know, if it were about everybody else, it’s leaving us. We’ve bought we bought the whole book and we’re staying in one place. So she opened our minds to be free and express herself regardless of the consequences.

Interviewer: And do you think one of the keys is that she did it through stories for another?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Yeah, talk about that. And she did it through her her personal persona. Her poems are stories of performances. A statement she Frida’s in a very important spiritual way.

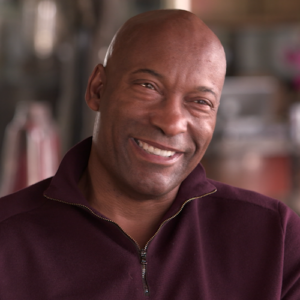

Interviewer: Let’s move on to a little talk about roots. How how did Roots come about? Or how did you first hear about it? Or where were they, you know, Alex Haley I mean, how did how did that come about?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Well, it came about fortunately, the way I came into Roots got I was fortunate enough to be on that list of actors, which would be roots. And I wanted to play Kunta Kinte, his father. And then I wanted to be somebody more important than James Earl Jones. You know, we thought about we wanted to be in roots. It was so important for us. I got the part, I suppose I’ve gotten and and Maya got the part she should have gotten, and so did Cicely. And so LeVar, sort of James, Earl and J.D.. All of those people got the participants to him, including O.J. Simpson. He was the one who wrote it. But we got the parts we’re supposed to go. Some clever, divine intervention got us the right part. Alex Haley We grew out of the merchant marine vessel that he wrote this thing and it exploded on him. It happened bigger than anybody would expect. But here we are about to express ourselves after all this time. And then I remember the people in the television network saying, oh, we’re going to lose some money on this one. Oh, when we got this contract with David Wolper and he’s a troublemaker. But I respect and I let’s put it on one day at a time, get rid of it. And that’s how Ruth started. And you see what happened. The stuff that we knew all along. Some of us did not. And we talked about in living rooms and kitchens with one another at churches. Now it’s global. And the reception was outstanding, obviously. And it’s nice to be part of that family, that legacy of Roots. Now, even today, we’re kind of piggybacking on that legacy of Roots. And Maya is a very strong personal persona for that poetic growth that she does with her books and her actions. Very indelible.

Interviewer: You’ve talked about and effective. Can you talk a little deeper about that? Because when Roots came out, it had an extraordinary impact on our culture, both for whites and blacks. So it seems like few shows in American television have had that kind of impact. Can you talk about that? What what impacted roots here? Well, the.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Impact that Roots had on not just America, but the world. It’s a story that nobody really knew how real slavery was and how slavery came about. Still want to talk about. But that story about doing the research and bringing those people from Africa in the middle middle passage and putting them in slavery to create an industry and help America in the South. These specific visceral relationships that was covered at that time quite dramatically was a revelation because you could read about it in a little bit in a chapter in history book. You can’t get the feeling of how it really was. You can hear some songs, you can read the slave songs. I used to sing folk music and all the slave songs and about how hard it was. I get stories for my great grandmother who was a slave, and it wasn’t all bad, but it was horrible and not all bad because you got used to it. It was the revelation that we knew basically what happened because we hear stories, but the world didn’t really realize the horrific stories that had been doing those hundreds of years and how it happened and what happened specifically through Kunta Kinte. So now everybody knows we thought that was going to be over and that was it. And the world responded, shut the world down, and they would still watch it if they put it up and watch it again, which we got 12 Years a Slave and all the things happening now, Selma, all that stuff is quite important. We’re going to get to that place where good and evil level so we can go to talk about the other stories about us as a people, about the Harlem Renaissance, which may have talked a great deal about it and the the great people there, the great cowboys and the soldiers. And there’s a bigger story. Roots is not finished, but you got start in the right direction.

Interviewer: Do you think it opened a dialog? For both whites and blacks. Their time to talk about something that sort of reminds me of The Hobbit. There’s a similar mini series called Holocaust.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Yeah, well, yeah.

Interviewer: Which, which, which for the first time, people started talking about the Holocaust. No, everybody knew about this. But it’s similar with roots. I mean, you know, slavery was known, but it wasn’t really talked about. It wasn’t really addressed, as we always refer to it as our original sin in America. Mm hmm. You know. Do you think it had that kind of effect?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: I think it had the roots and an effect. And it did create a great deal of dialog on all levels. I didn’t realize it made a lot of friends, made a lot of enemies, but it was up above the table as it is today in everything that’s above the table. Thank goodness for the computer and the Internet. There’s no secrets now, So the subject is still being discussed, obviously, today. And as soon as we get finished with that, then we get rid of all those poisons we can get on with this this global community that we need to have. But most again, Maya was in the middle, along with the James Baldwin’s and people like that, opening up those stories in such an eloquent way, too, to help us grow with the information that we need to have about how horrible slavery is anywhere. Holocaust did that, the Roots started that, and it’s still not over. As you can see what the productions today and we’re still on the Promised Land on the way toward it a little faster than we realize because things are coming to a head. But back in those days, it’s supposed to be taboo to speak like that. And we did it on international television is history.

Interviewer: That’s great. One more thing about that. Can you describe I know you weren’t in the segment that Mae is in because she plays Kunta Kinte, his grandmother, And you were Fiddler later on. Mm hmm. In the series. But can you just describe to us what her role was and what her what you thought of her performance? Oh.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: What I thought of my performance. I don’t know. She said she thought about it. She just did that role. She had all the information in her system, as Cicely had. She was a woman, a consummate expression of her art and of her soul and roots, especially because it was a triumphant part to play Mother Africa. You know, the mother, The grandma. She was the one. She was the matriarch. And she relished in that role. And she still relishes, even today, even though she might physically be gone. She’s relishing as the matriarch, the poet laureate of us, how her statements ring so true. You read a poet or you read a moment about her, and occasions come up on a daily basis when you talk about it. The first time I heard about it came from Maya Mean, the first time I heard Maya talk like that was 1962. So her legacy has gotten quite strong, indelibly.

Interviewer: So it’s great. You knew us. Obviously, you stayed friends with her for all these years. Yeah. You’ve been down to Winston-Salem. What was it like to just hang out like she was a great cook? I mean, what was it like for you to go down and visit her? And what was that like?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Well, I went down to visit my I knew I was gonna get me some good food, but she’s she was like my great grandmother. She was very cantankerous. You don’t put that much salt in the cornbread. I mean, that’s what it would of the Fort laureate. Where’d she go? Just a minute. You know, let me show you how to mix this with that. I said.

Interviewer: Well, I know.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: But that’s sort of how she was imbued with our roots. That’s who she is. And so she had lost patience, but not so negatively. So she just first alerted my great grandmother first in that, you know, I had this story about my great grandmother, which and in my later years was kind of guilty of the same forgetfulness. And one day my great grandmother and her two friends were over 80 years old. My great grandmother died at 120, approximately more or less. But she was the mother of the First Baptist Church of Sheepshead Bay. And I’m sitting in the kitchen drinking coffee. And one of the ladies said, I think I’m getting a little senile because I went to get something out of the refrigerator. And I stood there with the door open for 5 minutes trying to remember would I want to get a refrigerator? And secondly, this is you know, I know what you mean because I stood in my closet for 20 minutes to what am I doing standing in the closet? And my great grandmother said, and Maya Angelou used to be ashamed of yourself talking about how old and senile you’re getting. I’m at least ten years older than both of you. And thank God. Who is it? Maya was like that in her later years because she was very cantankerous. How many times did I tell you to bring me some milk and you bring me some buttermilk? She asked for buttermilk in the first place. But when it came to talking about African roots and a legacy, clarity came to her. So the day she died, she was clear as a bell about her job in life and transforming her information of her knowledge. To somebody else. It’s this amazing process. But we have as a legacy, I guess other people have it. But we could be senile. We could be nervous. But when it comes to an important message, clarity, it’s. And mine was not that way until she left the plant. That’s our legacy. So something about that, about people. And she or I remember her being dreamily clear about certain things, about her roots. Of course, the poetry.

Interviewer: She did not, as we noticed, she did not suffer fools very easily.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: No, those who did.

Interviewer: Over 18 told us some stories about, you know, somebody who. The one story I think you had made a A.K.. Yeah. Or something at some party. And that person was actually asked to leave the house. Yeah. I just retracted her knowledge, and I’m going to leave.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Ain’t got no time. There’s no time. She had. She was kind of impatient with the unjustified beliefs. If somebody was wrong, they were all stupid. She was like that all her life. But now, with that life experience, she really stood on her. Great grandmother, grandmother, matriarch, wisdom with no time. No time for. I’m in a bit of a pawn for coke in the house. She was so browbeaten she didn’t know what to put on since she didn’t know what to do. But I did the cooking anyway. You know, Nancy, she was a good teacher, but she had a short temper when she figured people ought to know better.

Interviewer: This is a tough question, but I just wanted to know when you first found out that Maya had passed at the end of May. What went through your mind? When did you first hear?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: When I heard that Maya passed. Everything is quite as it was just now. I got quiet in my system and to stop and reflect on all the experiences I’ve had with her. I was in this room. And it was a great silence about everything. Everything stopped and the memories of her, all of them came to pass. She said yes to my foundation. The foundation is called the E! Racism Foundation. She was going to be the first board of directors. So there’s a lot of lessons that she told us. Here’s what the foundation should be about. So I was very grateful that they had her to lead me to others, and she was leading me to others. And I had a lot of weekly telephone conversations with her. And I did a show, went to her house, and we we emailed a lot of one another and she said, What’s going on? You know, she pushed me a lot and gave me some lessons about what direction. And those lessons and the lessons that we used to give from one generation to the next, maybe three or four generations ago. That’s the inspection before I hand touch the doorknob. Certain things that we were taught by our elders, our hygiene, self-respect, our respect for the opposite sex, and respect for the elders, knowledge of our culture, conflict resolution, physical fitness, spirituality. Before I hand touch the doorknob and then we went out there, we were protected a little bit and going to school with that mindset. Conflict resolution. So somebody who does not look or feel or believe in us, we could get along. So then when those kids went to a school to learn they were there, receptive to learn and do positive things with it rather than negative things. We used to do that naturally, starting in Africa. There was something to do with each generation, and she reminded me of that. A lot of us that we have to go back to those you call thrilling days of yesteryear where as soon as you were able to walk, there was something you did to benefit the whole tribe. At three years old, you go and gather eggs and eggs. Everybody would eat milk, a goat, and everybody had the goat’s milk. And five or six, there was something else she would do and take her the goats and stuff. And you had 15, you know, you know, every age there was something to do. And we began to lose that as we got into integration. And she got a little more upset as we started losing those basics, the ability to cook a sweet potato pie properly, the ability to pray, the ability to read about your people and then to grow on a daily basis started back in Africa and maintained us all through slavery. And we started as we started to become equal, we abandoned the wrong things. And she brought us as a reminder that perhaps in our freedom, we have to go back to those roots and add that to the whole melting pot of America, indeed the world. Those are her words. That’s her everyday action. We have something to offer society and it’s positive, not negative, and that there’s some kind of resistance to it. But in spite of all of that, it’s probably one of the salvation of mankind. Those original African roots that went through the Middle Passage, through slavery, through recovery, and now with our freedom with Maya and Dr. King. There are some value systems that are indelible that survived all of this time that’s more relevant for the salvation of us all today. So this nothing should be in the way of that and we should not be ashamed of it. It’s our legacy and we have something positive to add to the not only the American soup, but the global soup.

Interviewer: Something that you said that really kind of jogged my memory the whole. You all met socially off stage?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Yes, we did.

Interviewer: And one of the things that we don’t have a good picture of was who was Maya Angelou? Socially-wise. I believe she had a sense of humor. I know she was still very serious, but that part we don’t have. Let me know when you guys are ready to go. You’re ready to go?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Well, just well, to answer your question about the social know, we were together. We were the whole bunch of people. There was two different sections. There was the black thing. We all go uptown and have chicken waffles and have parties. I remember a party, and she could party and she could dance. She was a dancer. She did that for dancing. She did that with the the Ned Williams dance troupe. And so she she was completely artistically, she could dance. You could sing. She could live. She lived wonderfully. And the party times was hilarious with her and Godfrey, Cambridge and. And Josephine. Promise. I remember Lena Horne. Remember all of those people. And we kind of was a tribe of people. But then again, we started having parties with the Jane Fonda’s. So it transcended into this wonderful renaissance kind of society that was offstage. But it was impressionable enough so that when we did performances, those people would show up and bring their friends. So the society grew and grew and grew. Part of that renaissance of art that happened for the for about 50 years there. I grew up in Brooklyn with some of those teachers, and they still were alive. So, my friends, today as a result of that society. One of the highlights of that society was my on off camera, offstage and on stage and on camera. She was very vivid.

Interviewer: When you said that she had a good smirk, he had a love hate relationship. Yes. And I imagine you all did parties to sit around and had drinks together. Mm hmm. What were they like? Besides, if there’s a story or something that gets us to what she said to me. She said to me, You know, I am. And I always was a very sensuous woman. Mm hmm. And that her sensuality was not something that was not. Why are you laughing?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: I could see. I can see of Mr. McKee frowning whenever she wanted to dance sensually for anybody. He figures that she would dance sensually only for him was in African culture. So she expressed her freedom, which is not really very African at the time. The man was in charge and it’s deep in his roots in the system. And when a woman expresses itself and then tells I’m not ready to go home. It hit the thing. So it was a love hate, Not love hate, but it’s an ill fitting love. So we’re going to be getting back to that today where there’s a a marriage of those two. But for all of this time, the symbol of Africa, the male symbol of Africa and the female symbol of America, African and feel ill fitting, also a portent of what some of the headlines are saying today, that ill fitting glove of whose role is what. And it got quite serious from him. He would leave.

Interviewer: He would actually leave. He didn’t like her to express her.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Well, he will. He would he would he he he wanted to leave Maya some ten times that we can remember. And every time in a party when she would have a little bit to drink and he would be drinking, he’d be an African man, a gentleman based on the roots, what they do in their society in Africa. Now, based on my roots in America, she is getting her freedom, she spreading her wings. And she is an artist to express myself. And back in those days. And what would she be? Quiet and take care of their man. And those cultures really rock. But then probably when they alone, there were mad, passionate lovers. A magic story. Eventually it gets a little bit over too much and I’m gone. And one time she said, Go. But they were there for that one particular purpose of rubbing together for that time. You know.

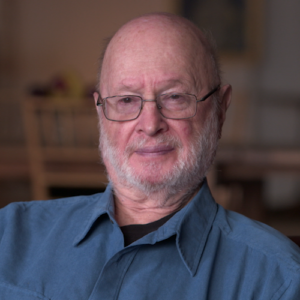

Interviewer: Did James Baldwin ever join your group and did you notice the relationship between he and Maya.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: James Baldwin and Maya Angelou? It was another love hate relationship. James Baldwin was a very brilliant man and they had pretty hot arguments about Africa and about African roots and rights and stuff. Sometimes I would overhear and sometimes I couldn’t because they were at the top of their voices. They didn’t fight so much. And then once again, I remember the respect that they gave one another, the excitement that they both are expressing themselves and both brilliant people in a room. After a couple of drinks saying what they really feel. And I remember those days, a very necessary, painful growth on all of our parts. But they were in the middle of it. I remember Diana Sands. I remember the late Paul Robeson. Remember Josephine Baker? I mean, I remember those people. I was a young guy in a crowd, in a sense, without that experience of race, because I had a different upbringing. So I had to learn. But it’s better to learn when you’re a little bit more mature. So and so those values just kind of less that instilled in me today. But I overheard the story Maya and Sammy Davis Junior to different people. Is respect politically different? Finally, maybe they might have made peace, but she had to make peace with everyone in her later years because she got much smoother with her expressions of more tolerant because she was fighting the devil, the white devil, as she called it. And it kind of smoothed out and she became a poet, a brilliant woman. And I remember those transitions. I remember her being very angry, very angry, too, to use to to smooth her life out, to be the poet laureate of America and possibly the world took some changes that she had to go through. We all do go through those changes, but I had a chance to watch her.

Interviewer: Did you have any knowledge of her relationship with Martin Luther King or Malcolm X?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: The only knowledge I have with her is with Malcolm X. Malcolm X was a very large influence in my life. But then again, there was again, in retrospect, the relationship with Maya and Malcolm X was the male, the black male and the black female. Once again, in retrospect, there was always that rough edge. Although there was a mutual respect, there was 5050. I’m as strong as you are. So what I see as is important is what you say. We were growing at the time where making those peace with the black man and the black woman and Maya was a symbol, and so was Malcolm X, So was Max Roach. There were symbols as ill fitting love until you make an adjustment.

Interviewer: I think that is I think I have one other thing here, because I loved that interview. And this one is is also around the area of the blacks. You answered it, but I want to give you something that I was told.

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Okay.

Interviewer: Well, we spoke to Bob Loomis, who was Maya Angelo’s editor at Random House for over 30 years. He wasn’t she wasn’t writing for them at the time of the blacks, but he described seeing the blacks. It’s the first time he had seen Maya Angelou. Mm hmm. And he also said when he left the theater, he was ashamed to be white. Reacting to that statement. Why would the blacks put someone in that, a white person in that position?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: It’s very ironic that the blacks and the whites would be in the blacks would put those whites in that ungainly position. But and it was ironically written by a white Frenchman. Avant garde. But it’s a clever depiction of how we feel when they do certain things. It was done in a beautiful artistic way, but it frightened a lot of people because they had no idea that they were doing it. So there’s a fright there. So now that we know we’re doing it, then you’re angry. What are you going to do to us? Kind of emotion. So there’s a fear that this one woman fainted and a man had a heart attack because we were so influential, impressionable that we thought that we had the prisoner. That’s one of the ambiance of the play within the play. So I guess we did it well enough for that reaction to happen. And that was the meaning of the blacks.

Interviewer: Last question. What do you think her legacy is from civil rights to acting to poetry? To the inaugural poem. What? What is her legacy?

Lou Gossett, Jr.: Oh, her legacy is enormous. It’s just a reconnection with a proper roots starting back in Africa. Our growth as we go from day to day, continuous knowledge of learning and passing the message on, paying it forward as they see today. She did it almost all of the time, and then she got blessed. And it’s a selfless natural function that she did and made examples to people like myself. You don’t gain anything except a glory for being when you give it away to keep it. That’s a natural function.