Interviewer: So you’re saying that your name is…

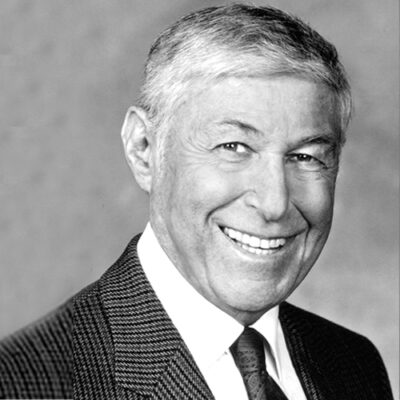

Lowell Bergman: Lowell Bergman, l o w e l l and one N at the end of Bergman.

Interviewer: OK, so tell me a bit about your background and how you got to 60 Minutes, please.

Lowell Bergman: I came to 60 Minutes after spending about six years at ABC News and they had moved me to New York to play executive for a little while. And I insisted on moving back here and I did that for about a year. And then we decided to part ways. And I got a phone call from Mike Wallace asking me if I wanted to go to work for 60 Minutes, and to which I replied, Yeah, sure sounds great, Mike, but I got to live here in Berkeley. California, mm hmm.

Interviewer: And what do you say?

Lowell Bergman: Well, we don’t like to do things like that, and there was some resistance and I just said, well, that’s my precondition. They flew me to New York, we met, talked about it, and eventually they were able to get the approval of upper management initially on a trial basis. But the trial became custom and I never moved.

Interviewer: People who say that you get to 60 Minutes by something happening that brings you to their attention. What happened at ABC that brought you to their attention?

Lowell Bergman: Well, I had been involved in both the startup of 20/20 and and of Nightline, and I had done a bunch of pieces that apparently Mike watched and liked. I think the last one he was talking about was I did a piece, interestingly enough, with Johnnie Cochran in the Ron Settles case, a story of a Long Beach state halfback who drives from this little town called Signal Hill, which is part of Long Beach and winds up hanging in the jail cell. Really? Yeah.

Interviewer: Knepper to the attention of Mike. What was the first piece then you worked on?

Lowell Bergman: From when we worked on a piece that was called The Coronado Mob. It was about a group of high school students in Coronado, California, Navy brats who decided that they were going to get into the marijuana smuggling business. They were surfers and they live right near the border and they team up with their high school Spanish teacher and eventually become the largest dealers in tie sticks and various forms of marijuana for a number of years became a multi, 130 million dollar business. Something like that, really.

Interviewer: So first shoot with Mike Wallace.

Lowell Bergman: Oh, well, the first shoot was we never really worked together. And he arrives and we have an interview with the head of the DEA in San Diego. This is the day of film, you know, in nineteen eighty three. And we’re setting up a sit down interview the guy and he’s getting ready. Mike sitting down and the phone rings and he says, mm hmm. And he puts the phone and says, well, I just got a call from Washington, says, I can’t do this interview. And that’s the way things are in news, film production and whatnot, but Mike, though, because the cases were still pending, because part of it had to do with a one of the chief defendants, the high school teacher in this case, who had rolled over on his former students and they let him walk. So there are a lot of different issues. They were they had rated a law office. It was the first case involving a federal government search of a criminal defense lawyers offices where they taken all his files out. So the whole issue of when as a lawyer, part of the criminal conspiracy, when he’s just a lawyer in this particular instance, this is one of the precedent cases. So it’s very sensitive. So he said, I’m sorry, I can’t talk or make turns to me. Looks at me and he says, follow me and he gets up and. I follow him outside the building into the parking lot where I proceed to get. Dress down is only the only way I can describe it in at a decibel level that results in people opening the windows in the office building to listen.

Interviewer: Wow, very shoot. First interview.

Lowell Bergman: Welcome to 60 Minutes. Right. That was. Oh, you know, you wonder at that point, what are you doing here? Who needs this professional level, I just kept trying to go through the day and do what we had to do and it worked out, I took a little revenge on Mike. A little later in the shoot, things started to gel and come together. Part of the shoot was going out in a cigarette boat, basically a high powered motor boat that they used for smuggling. And we had two of them. One was Mike with a smuggler in the boat and the other one with a camera. And Mike gets in the boat and he didn’t realize that this boat is going to go 100 miles an hour. So I can hear him screaming on the radio, Mike, as we’re heading out, you know, off offshore and then we get out there. And lo and behold, our camera broke. So we had to go back and leave Mike bobbing in the ocean for 45 minutes because he felt annoyed he was a little longer.

Interviewer: Now, you also said that he he likes to reproduce the sort of shoots you said you get on a shoot with him and he redirects the lights.

Lowell Bergman: Well, Mike, I always like to say about me that I think he’s quoted once said that the Bergman wants to be the executive producer of the Charisma and that the producer, the reporter and the cameraman. Right. And I think that’s more Mike, what really Mike is describing himself, actually.

Interviewer: So he changes the lights right now, what was the first screening like then for you?

Lowell Bergman: The first screening was really interesting because. I got exposed to the storytelling ability of Don Hewitt. We showed him a very rough assembly. And because it was my first piece and, you know, anyone would be nervous on your first piece of what’s going to happen and really what happened was and I think this has been Don does this regularly with people in their first screening. He just went to work suggesting ideas, things that you hadn’t thought of from a reform point of view, where to set the story up, make it a little cuter. And and he actually went back into the editing room with me and worked on it. Now, that had never happened to me in the six years I was at ABC at the network and never had an executive producer come into the editing room. Right. And, you know, usually they tell you, change this, do that, make it this way. You take notes, you go and do it right. This guy actually came back in and said, here, just we’re going to do this, this, this. I mean, absolutely. Hands on. You know, don’t worry, this is going to work. So in that sense, it was great and the piece came off really well, and this was the piece you were just telling me about. Yeah, yeah. So I went from the depths of, you know, what the hell am I doing here? And who is this maniac to. Hey, they’re going to help you make it even look better. And put it on the air and you sit there and you for the final track, and this is 83, so Mike is only. Sixty something years old and early 60s, and you hear this voice come out of the loud speakers, you know, the speakers in the sound recording room, a voice that I had heard since the mid 50s. And it’s going into your piece. And so that was a positive experience.

Interviewer: Yeah, Haeju, it is interesting how Don does get right in there and that is unusual. That is an unusual aspect of 60 Minutes from everyone’s experience. You always agree with his. I mean, what do you think happens when you disagree, shall I say?

Lowell Bergman: You can fight with Don about it. That’s everything. I mean, you have to be. Willing to fight or after a while, you get you learn from hand signals in the editing room, in the screening room. Hand signals in the screening room and and eye contact with different people that maybe you shouldn’t challenge him right now. But what about tomorrow, especially if it’s a factual thing and I haven’t had too many disagreements with him. Actually, in a sense, if you understand that 60 Minutes is a form that both he has created and has become part of him, that he’s absorbed other people’s input at the same time that it’s his show in that sense. I haven’t had a lot of disagreements with him about what form he wants things in. It took a while to understand that he believes that the sound in the story is more important than anything else in terms of the storytelling, people being able to follow the story. That’s why you don’t see any graphic, Kyra, and whatnot in 60 Minutes. So it’s more of, I guess, the bigger fights I’ve had with Don, if there have been over issues or maybe if content in some way or another.

Interviewer: Talk to him just for a second about that that form to talk a little bit about the forum for me.

Lowell Bergman: I believe that it’s you know, it’s there are a number of ways to talk about it. It’s become the grammar of television news that that people have absorbed so that it’s almost in this in the United States especially. It’s an unconscious form that people have absorbed from seeing it so often and seeing it duplicated so often so that you if you’re sitting back there, it’s easy for you absorb information or what’s going on, because it’s in this comfortable form that Don really has refined in many ways. It may be a cliche at this point. You know, it’s it’s the 60 Minutes format, which is what? Well, you can you could close your eyes basically and follow the story in almost all cases, unless the pictures are extraordinary. Right. Everything is explained. All the basic things are explained by the storytelling is done by a correspondent. So, for instance, you would not be in the story right now. The editing is set up to the to a certain extent that it’s you hardly ever hear or see the producer. So it’s the adventures of the correspondent. Everyone has to speak clear clearly in English or it’s narrated over. I remember I did a story. It took me three weeks to get members, members of this Chinese organized crime group down in Southern California to actually go on camera and talk about working for the Taiwanese CIA and assassinating somebody up here in Daly City. Big international case, Henry Lukasz. But the guy’s English was he went to Stanford, but it was a little hard to understand. We narrated it over the whole thing. So it’s like wall to wall narration. So those are the really main main parts of the forum, I mean, and, well, the tight close up sometimes it’s not always that way, but the tight close up has evolved as sort of a 60 Minutes signature. But it’s not absolutely necessary and it doesn’t always work, particularly with Mike. You have do it tight close up of the correspondent.

Interviewer: They say that you never have heard of the format, how I understand it is the format. The format is such that the correspondent is never close to the subject, is always right.

Lowell Bergman: Oh, and the correspondent never loses an argument, but that’s become universal in television news, which is probably one of the biggest fictions that has been maintained, but it’s also part of that form that makes it easy for people to understand as part of the understanding process you don’t see on 60 Minutes and all the magazine shows the the correspondent never learns. Something through mistakes in the story, which is a normal way to learn things, you get it wrong and then you learn, right. But we oh, it’s all straight. Line, no dialectic. Right down, right down the line, unless it’s an interruption argument kind of thing going back and forth. And that makes the correspondant seem almost heroic. I mean, some kind of way, doesn’t it? Or yeah, or.

Interviewer: Without fault, let’s put it that way. What was your first impression of Don?

Lowell Bergman: Here’s this contradiction, he’s the boss, but he acts like the guy he met on the street. He was without it, seemingly without pretense. Which was unusual, I was, you know, I mean, I came from ABC where there was a number of executive producers who were somewhat Napoleonic, you know, they almost wanted to have their hand in their jacket. And here’s this guy who just seemed like he was talking vernacular and talking about anything that came into his mind.

Speaker It came right out his mouth. I mean, it didn’t seem to be any mediation between the two anyway.

Speaker What was being with these insights, I mean, as the same time, insights into the form into what you were doing, into the work? That were striking. I mean, you know, an immediate sort of vision, let’s try this idea, you know.

Speaker What was the word about on air 20, 20 from afar? I didn’t really know much about them in.

Speaker There was a Weston who was an executive producer and a vice president at ABC at the time when mentioning Don would sort of roll his eyes. I mean, he had been at CBS for a long time. And shake his head. But I knew nothing more other than that 60 Minutes was. What is the, in a sense, the most quality television news broadcast of its time?

Speaker Yeah, I haven’t done any research on it and I really haven’t checked him out, but when you went to 60 Minutes the early 80s, 60 Minutes really was on top.

Speaker Yeah, they already had been. Number one, they were worried about staying in the top 10, right.

Speaker Dance, I don’t know, are you aware of the documentary that he produced on Frank Sinatra?

Speaker I’ve heard about it and every time I mention he mentions it all the time. I mean, you know, I’ve just never bothered to look at it. Apparently, Frank didn’t like it, even though it was sort of a puff piece.

Speaker Yeah, I mean, it was a positive late 60s, he did it right before it was actually mid 60s.

Speaker Mid 60s. Yeah. And then Sinatra won’t do anything with them since then. Or he doesn’t understand why.

Speaker I was just kind of well, I’ll go for a different direction. Do you think there’s similarities between Don Hewitt and the early men who started howling with the Samuel Goldwyn’s, the Jack Warners, the.

Speaker The early studio heads.

Speaker You may not. Well, you know, I’m sure there are similarities. I don’t think they got as involved in the actual production.

Speaker They were dealmakers coming out of the garment industry. And maybe there’s some of that ethos. And, Don, the deal making, wheeling, dealing, you know, let’s do this. Let’s do that. I think that the thing that sets Don apart is, is his integrating of his form that he’s helped to create so that and either through luck or through deserving it, having this show that’s lasted with his influence in this audience. So he as a result, he’s become a major influence on the way people learn things through television and the way they understand things.

Speaker Absolutely. And we kind of have an American history as seen through the eyes of 60 Minutes.

Speaker Right, or even through the life of Don Hewitt, I mean, you go back to the Andrea Doria, you go back to the Nixon Kennedy debates, you go through Edward R. Murrow and so on.

Speaker Absolutely. You’ve worked with for quite a few of the course fans abundance over the last year. And you’ve worked for quite a few of the correspondents over the last 15 years. I mean, you worked with with Wallace. You worked with Kroft and Harry Reasoner. Tell me a little bit about differences, Diane, and tell me a little bit about the idiosyncrasies of working with the various producers correspondent.

Speaker The differences, the main difference for a producer, the two main differences for a producer or one, how much the correspondent is actually involved in the story, both in terms of questions that they asked reporting that they may try to do on their own, and the other is their ability to perform on camera and how they perform on camera. Just in terms of the shooting of the story, the editing, how much is involved and how much they want to control that story.

Speaker So let’s start from the beginning. We have Mike.

Speaker Mike wants to, in a sense, do everything, give it to you again.

Speaker Mike wants to do everything and he understands.

Speaker Most of the process does very well because he’s gone through all of it. I mean, he’s had to go from film to tape and he’s gone through editing and writing and so on.

Speaker And so in that sense, he is the most complete correspondent. And at the same time, the most you know, it’s hard to describe Mike Wallace because he is somebody who has invented the tough interview and then you’re with him doing the tough interview. How can he be doing it wrong? He did it right. He invented it. So it’s hard to compare him to anyone else. He’s also got a you know, he has this unique personality that went along with Hewitt that you just you couldn’t invent it.

Speaker I don’t know if you’d want to, but you could invent it, Harry Reasoner, at least in the years that I worked with Harry, was in failing health. And as everyone says, a great writer are really laid back in many ways was his personality. He was it was kind of Mr. Natural, you know, in the sense of a natural guy. He wouldn’t push himself into a situation and he was able to get people to to build that level of empathy. In a very genuine way, do you regret your copy and rewrite it?

Speaker Yeah, rarely he would change it to his words or sometimes write stuff, but I have a lot more freedom with Harry to go off and do the reporting, do the shooting, even do shooting interviews myself and then cutting myself out in order to help the story work. So in that sense, the stories became the content anyway, became more my own creation, I had less of an on camera person to a gorilla to, you know, maneuver with the dance with.

Speaker Diane, Diane is, in my opinion, is a great reader.

Speaker Steve Kroft. Steve Kroft.

Speaker Well, he’s he’s got good editorial judgment in terms of stories Krofft is the most frustrating person to work with in terms of writing, he just will take a script and disappear into his office for days on end while you’re sitting there waiting. So it’s very frustrating in that sense, I.

Speaker But he gave me I mean, he was he was relatively easy in the sense of story selection and so on, I didn’t have to fight with him about whether this was a story or that’s a story. I just went ahead and did them.

Speaker But like you had a fight with, you had to convince him you got a make.

Speaker You always have to you always have to keep him on board. I mean, first of all, you got to get, you know, OK, we’re going to do a story together. Fine. Right. Then you researched the story, right. And he looks at and says, I don’t think it’s a story. I mean, what do you mean? You know, I think it’s a story this guy is going to go on. I don’t think it’s a story. And then walk out the room. Or, you know, with Mike, it’s a constant, you know, back and forth both sometimes incredibly good editorial questions to check out. And and then also a lot of, I suppose, reflecting his own insecurity about whether it’s a story or not, but pushing it on you, you know, or you give him a memo and you say, well, why don’t you tell me about this before I said, Mike, you don’t want to give it too much material, right? And they know just you know, it’s that he is like Don. Yeah, they are. I mean, they are very much I think they’re in a sense the same generation, although Mike is a little older, they come out of, I think, the same apparently out of the same sort of social cultural military of New York in the 40s and 50s where they want to go get the story. You can almost see them with their fedoras on and a little press ticket in their hats. You know, that’s how I like to see themselves, even describe themselves that way. And the problem is you don’t want to get run over by these two, you know, guys whose energy level is already very high. When when you see the two of them together, you know, you want to step out of the way.

Speaker Ed Bradley and is really one of the few people I’ve met. Who’s on camera, who’s a star, who has maintained a clear place in his life for something other than work really, or tries to as much as he can. You know, so he’s he doesn’t get in the way of the production and he his on camera abilities are great, so he adds to it.

Speaker You know, when we talk about television production, you’re talking about a group process, however, screwed up the various and neurotic. Various people are in the process, however big the salary differences may be or the recognition differences may be in the end. It’s a group process. It’s unlike print reporting, which I used to do. It’s not one person. That it rests on the reporter or one person, and is that his or her editor? It’s this group dynamic. And so the most important thing is that the various people bring their talents or their abilities to this group process and make it all work. So if the person on camera, not only like people say about me, that I have a voice for television and a face for radio. Right. So if the people who are on camera can can articulate the story, can do the questions, can deal with the person on camera, can help with the writing, can deliver a narration that has more training, more impact in terms of the voice it adds to the whole process. And when those things happen on certain stories, for instance, as a producer, you always remember then that when everybody is working together and the product usually is that much better because it happens. It’s going to give me an example. Well, the most the one story that I can think of that really just everything fell together on was when I went to Lebanon with Mike. Actually, I went there first. This is 90. Beginning in 93, I think it would be beginning and we plan in interviews with the Hezbollah or the, you know, Hezbollah, you know, those guys, you know, they used to keep us hostage and they aren’t known for being very happy about Jewish people in general. You know, I mean, they say they’re not prejudiced, but, you know, it’s not a recommendation for longevity and. The people who helped set up an old friend of mine who helped set up the liaison with the Hezbollah, the camera crews that showed up, the whole operation on the ground that took place was very cooperative and productive for like a week before Mike arrived. Mike arrived.

Speaker He didn’t bat an eye.

Speaker I mean, some of the places we were going because they were pretty well, I mean, you know, here we are walking around the southern suburbs of Beirut, you know, and we I had arranged for two for a squad of Lebanese army troops as our bodyguards in exchange for some dealings we did with defense minister in Lebanon.

Speaker They would not go with us into this section of the southern suburbs. They waited outside.

Speaker OK, they couldn’t go in.

Speaker We shot this whole thing with Mike on the ground.

Speaker You know, after a week of setup, we shot it in three days, we got on a charter, we flew back to New York via England, and we were gotten to New York on a Tuesday night and it was on the air that Sunday. And the whole process was just a process where everybody did the best they could do. Everyone added what they could add, both from the shooting to the editing, my editor, Tony Baldo know who was the champion at staying up all night?

Speaker People in New York were no hassle, you know, in terms of, you know, Don was just the only argument I had with Don was about I thought the audience could use at least a minute of history. But, Don, nobody cares about that. Take it out. Do the things I would have liked in it. Yeah, right. But the process itself was pretty rewarding.

Speaker And Mike, who apparently I didn’t find out until somewhat later, had been going through various emotional battles himself, just was straight forward through the whole thing.

Speaker I got a pager going off here, going up. And I’ve got to ask you one more question. After this ten year old, you do your picture, OK? Is it now? Yeah.

Speaker How did the title come about? Well, that’s a typical Don Hewitt situation.

Speaker There we are in the studio, actually in the control room because they’re still doing the art of walking away and because we’re rushing here and Don turns to me and says, we need time, we need title. And I said Hezbollah now. And something similarly mundane. And then how long are you in Beirut? Oh, I was there eight, nine days time because no, not you. How long was Mike there? Three days.

Speaker He says. That’s the title Three Days in Beirut, I said, Don, I was there for like nine days when we got my ass shot off, he says. Nobody cares about that. Nobody cares about that.

Speaker That is a typical down story that is perfect. One of the thing about the correspondents, a lot of producers have related their relationships with the corresponds almost like a marriage, so that it’s sort of like a you know, it’s a very tight relationship. Is is that how you see it? I mean, your relationship, especially with Mike, which has gone on for many, many years.

Speaker Marriage is not about a marriage.

Speaker I’d say it’s a partnership, and as I said, I’d say it’s a partnership and it has to be because you’re part of this group process and doing the work again, forget who’s on camera, who gets the money, who, you know, whatever, whose longevity it is for the process to work. It has to be a collective partnership. It has to be a level of trust developing. And in the course of one of the first two stories or so to continue that, you can actually get all of this done. There has to be some level of mutual support, symbiosis or for it to work.

Speaker Other people have said that the criticism is sometimes like picking up again for some producers sometimes told me that they’re almost like free agents. They they they go from one producer sometimes to another, excuse one correspondent to another. The producers are like free agents in baseball. They could end their contract with one correspondent and move to another. Is that your choice or is that their choice or how does that.

Speaker It happens both ways. I mean, Mike traded me to Diane when she came on board. And so, you know, it depends if you don’t have a correspondent, you don’t have a job. Usually the very few people at a certain point the show changed. There was a time when producers, in a sense, had a little more power and could float more.

Speaker When was that?

Speaker When I first came to the show. I mean, most people were attached to a correspondent, but the idea of like moving around or being free floating wasn’t unheard of. I think so. Over the last, let’s say, decade, it’s become more and more formalized in that way. And also in terms of editors also really. Right. So editors tend to work for only one correspondent team, if you will, and associate producers as well, so they don’t float around.

Speaker Where do you get your stories from?

Speaker Well, for me, what I try to do is do stories that that in a sense.

Speaker In a way described as simply what I like to do is I like to do reporting.

Speaker In the vein of being a newspaper or any news organization, it says news magazine, so I tend to try to do stories that haven’t been in print or if they have been really haven’t become national stories and advance the story. So I have a lot of sources have been around a long time and I tend to work off those sources in terms of finding story ideas or subjects or things that we can that we can do.

Speaker Did you start actually as a newspaper reporter?

Speaker Magazines, mostly some newspaper freelancing? I started out in the underground press where I learned that I could apply with some friends again, working together, sort of the basic principles of sociological research in terms of who ran a city.

Speaker This case was San Diego and new stories which had an impact on what happened in the town, both with some of the wealthier people in town and the police department and the hierarchy of the city government.

Speaker Are you an outgrowth of the 60s? I mean.

Speaker Yeah, I’m a I’m a proud child of the 60s. I think I learned a lot and I learned how to make a living.

Speaker And I actually learned, having been disenchanted with the system, I learned what made it valuable. I think what makes it valuable to me.

Speaker So, yeah, there was a movement of new journalism that came out of the 60s and the Rolling Stone magazine, Tom Wolfe, all those people. Do you think that some people feel that 60 Minutes is an outgrowth of new journalism at the beginning? Do you?

Speaker I don’t know. I was at Rolling Stone. I was an editor there for a while in the early 70s, mid 70s. I don’t know that 60 Minutes is I think 60 Minutes is got a lot of 60 Minutes got a lot of, if you will, Caché because of Watergate more than anything else, I think the idea of looking in-depth at subjects and doing them regularly and time in a timely fashion and the relatively serious orientation of the program helped it a lot, at least for me in those days. Looking at it as a print person, it became more interesting as a show. I also at Rolling Stone, I learned how 60 Minutes worked because I remember the magazine came out every two weeks and invariably and I was involved in sort of the hard news side of Rolling Stone, and we would always get phone calls from Barry Lando or Marion Golden or some producer at 60 Minutes who wanted to put pictures basically in one of these longer print pieces.

Speaker Right. You share your sources with other producers sometimes.

Speaker Rarely. Depends, I mean, was rarely mean.

Speaker Well, it seems like a lot of producers come to 60 Minutes and their sources are this sort of their stock and trade.

Speaker That’s that’s their strength. All reporters have like a quiver of sources or a level of expertise.

Speaker If you’ve been in the business for a while, and particularly if you’re into doing what’s called investigative reporting. But I would just call it in-depth reporting. You know, you have certain areas where you develop things, but I’ve introduced quite a few people to people who know about what they want to talk about or whatever, I think. But that’s because my background is in kind of collectively working together, whether it was the original Arizona project in 76 where this guy got blown up, Don Balls and a bunch of reporters came together to do a series of stories or the Center for Investigative Reporting, which I helped start. Or so the idea or the the underground press stuff I did before. The idea of working together to me has always been much more productive idea in terms of doing stories.

Speaker Well, on that on that tone. See 60 Minutes as a family that is like that.

Speaker It is and it isn’t the basic production side is collective or is mutually supportive, the ethic that’s brought to this show both by the nature of the marketplace and also through the backgrounds of the people who run the operation is competition.

Speaker You said to me that on the phone we talked the other day, when an issue is not black and white, we tend to force it into a black and white mold to make good TV. Can you talk to me about this?

Speaker Well, as a person coming out of print, one of the hardest things and this is before I get 60 Minutes, one of the hardest things to get to make it in television news coming out of print, you have to start giving up all of these wonderful facts and information that you spend all the time gathering. You have to keep simplifying the story and honing it just like you will now in terms of 60 Minutes, so you can’t write a book and you can’t write a 15000 word article. You’ve got to get it all boiled down and understandable, particularly in the days before a videotape for a one pass for people to understand it and stay focused. So you lose a lot of the texture of the information and of the story. Things become simpler and to a certain extent distorted when you do that. And I still have that problem in terms of presenting a story. Many times I want to keep most producers do want to keep some little thing or this or a little bit more of that, or let’s draw this out a little more of what the time constraints or the priorities of the form of Hewett’s form force you to drop some of that, especially if you don’t have someone expressing it really articulately. I’m talking about the gray areas. So a person is either guilty or innocent. They’re either good guy or a bad guy. It’s hard to maintain the texture, the complexity of real life.

Speaker I’d love to have come back to without my question being there about it being how the nature of black and white, how that is kind of part of television. Can you give it back to me?

Speaker It’s coming from print. I mean, that whole. Yeah, just television. Just the short part of it. The fact that television has to be black and white in order for it to be. Well, because there. No, not my question.

Speaker So I can because people generally only see television once you can videotape and play it back, but generally only see it once. It’s got to be simplified for people to follow it for people who care about it. So the gray area is the texture, the the values and information in everyday life that make you understand that somebody may be a murderer, but you don’t necessarily have to execute them. That gray area is lost a lot of the times in television news in general, in the magazine form of 60 Minutes in particular, we have a little more time in the evening news to develop things, but we still have to have, in a sense, that casting that goes on in the story. So while you could get some of that gray area in a profile of someone, it’s very difficult to do it, on the other hand, in an exposition story about a particular situation.

Speaker We talked about stories that, well, we haven’t, but what stories can’t you do?

Speaker Well, me for 60 Minutes, if you don’t have anybody on camera, it’s very difficult unless the visuals are that really incredible, where the information is so wild that, you know, you can do it all in narration, but it’s hard to sustain 13 minutes of narration. You can’t do a story unless you have a correspondent who’s willing to do it.

Speaker I’m referring more to subject matter we talked about.

Speaker Well, I, I it’s hard to say what you can’t do.

Speaker You know that there are certain areas, some of which Don has made clear in the past and that people are inarticulate or, you know, speak broken. English is rarely going to do a story that’s like in a foreign language with translation unless it’s, you know, land mines or something where the drama of it I mean, the the pictures actually are so dramatic.

Speaker There’s no story you can’t do. You can’t say it in those words that you can’t do. There are stories that are easier to do and and the scale of what’s harder to do, you know, it may be impossible to do is on the other end, I was thinking a little bit we talked about big business, about an area that is generally, you know, there’s no blanket rule that you can’t do it.

Speaker The hardest stories to do for any.

Speaker Publication are stories, and it doesn’t matter if it’s print or TV or 60 Minutes are stories that come home that are either about the organization and how it works that you work for or the owner, the owner’s friends, the owners, advertisers, so that they’re the standard problem stories for any news organization. It’s a problem that exists, I believe, for 60 Minutes, although probably less so than most places I’ve been. I mean, the stories that have conflict of interest, well, conflict of interest or, you know, before you write about the organized crime or publish the organ, alleged organized crime connections of someone of great wealth.

Speaker You have to think once, twice, three times and realize that on the way to getting it published, for instance, all kinds of things could happen, Extra-Curricular things could happen as opposed to, let’s say, doing a story about a drug dealer who’s in prison like last week who wound up doing business from.

Speaker Jail, you can do him fine, just what’s he going to complain or, you know? Who’s going to who’s going to screw around, so it’s always true, I mean, I like to tell the story there. When I first got into television news, which was to work on helping create six 20-20, I first got in and was working on 20/20. They told me right after I signed the contract, supposedly hiring me to do corporations organized crime, what we call high end investigative stories. They told me you’re going to go investigate Chappaquiddick. And when I said I don’t do traffic accidents, they said, then you’re fired. So I said, OK. And I went off and I kept trying to kill the story, drive a car off the bridge with cameras. I’m sorry. Can’t do that. The state police won’t let you. Finally, after doing a lot of investigation, I discovered that on the morning of the accident, Teddy Kennedy’s first phone call was to his administrative assistant. And I wrote a memo and said, this guy hasn’t been interviewed. He wasn’t even questioned in the inquest. What happened in that conversation and where is he now?

Speaker He’s the vice president of ABC News. End of story went away. So it’s a when you get close to home, however badly they wanted this very, very much money they were spending on sending me and two other people actually to Martha’s Vineyard, you know, Wassan, whatever disappeared.

Speaker Did you do anything in Chappaqua? No, I don’t do traffic accidents. And Princess Di included. In the speech he gave the commonwealth in San Francisco talking about the Commonwealth Club. Yeah, the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, you talked about a litmus test. Litmus test. Yeah. Can you tell us your.

Speaker So basically, my litmus test for sizing up a news organization is are they willing to do stories about suppliers, about themselves, about friends of the owners, the owners? And how do they behave in those circumstances, how do they behave in a situation where the subject of the story is the same size or bigger than the organization itself? And then you can also determine the level of credibility you can have in that news organization, who to trust you, not to trust in what’s going on. And it’s not a question of going out gratuitously and just looking for those subjects. It’s that when those subjects happen, I mean, a good example, I would say, is the lack of reporting in the networks and newspapers on the owners of professional sports teams who they are, where they come from, where they got their money. Too hot to touch. There are a lot of different interests involved. Yeah.

Speaker And to sort of Jeffrey, what I can tell us how your relationship began with Jeff Wagan.

Speaker Well, there’s a more important question, I think, in terms of when you were asking about starting in, but. There is a group of people.

Speaker In the United States, who are more difficult to interview, especially on the record than almost any other group. They’re not CIA agents.

Speaker We get them all the time, they’re not mafia chieftains, they’re corporate corporate executives, people who have served in major corporations in positions of responsibility. And as corporations become much more important, they’ve always been very important. But now they are basically the masters of the universe. These people become much more important, it seems to me, from a public interest point of view, reporting point of view than ever before. And you can count on your one hand the number of corporate executives in the last 20 years who have ever gone public and talked about what actually goes on inside the organization on 60 Minutes, on a New York Times anywhere.

Speaker And that’s what Jeffrey Weigand. Was for me.

Speaker I was not a antitobacco activist, I smoked for 20 odd years, I never asked for money for it. I didn’t even occur to me when I first heard about Jeffrey Weigand that it would have any in a relationship with Lorillard Tobacco and Larry Tisch, although I figured that out pretty quickly. It was the idea that a corporate executive who had insider knowledge might be available not so much to spill the beans, even to me at that point when I first heard about Jeffrey because I had a pile of documents that had been dropped on me from inside Philip Morris and by the issue of fire safety and cigarettes.

Speaker And if you read these documents, you thought you knew what they meant. But as my associate producer at the time, Debbie DeLucca Shea, now to Lucashenko, I said, yeah, I think that’s what it means to.

Speaker But I wouldn’t bet on it because there would be words in these documents that are not in the Oxford Dictionary. So it looked around for who could read these things authoritatively and you could not find anyone from inside this tobacco industry who was really available to talk. So when I heard that there was a guy who might talk.

Speaker I was attracted to that idea, and then when I heard he was a vice president, I said, well, that even be better if we could get him to talk.

Speaker Now, these papers literally arrived on your doorstep.

Speaker Yeah, well, I tell people often that, you know, there’s a whole thing about confidential sources that not only is it done very lightly, a lot of times in the news business, but people don’t realize that a lot of ways in terms of litigation situations where a confidential source is revealed is that they ask for your notes, your files and the company’s expense accounts and everything else, and that’s how they find them in litigation. So if somebody says that they have something or may have something, I usually tell them, send it to me in a plain brown wrapper or no return address or have it delivered to my doorstep some way. Just don’t put any return address that’s real on the box. And that way I can testify that I don’t know where they actually came from. I could guess, but you don’t guess in depositions, you know, gets on the stand.

Speaker Right. So you knew you were going to be receiving a box of papers from Philip?

Speaker I thought I might be receiving a box of papers from Philip Morris.

Speaker I see. And so, you know, I had these documents.

Speaker I looked like an interesting story. A hundred kids die every year in fires caused by cigarette. Cigarettes are the biggest cause of death by fire in the country. I told somebody in the public interest community who is involved in this issue that I was looking for someone to read the documents. A couple of months later, he called me and said that he had just talked to somebody named Jeffrey Weigand, who apparently was in the middle of a big battle with Brown Williamson Tobacco. He had met him because they were on some congressional commission together and he had been the vice president for research and development. And this person said, I gave white man your phone number because he said he would talk to you. That was the first lead that was like in September of.

Speaker I want to say September of 93, something I think it was.

Speaker Now, you did not meet him until February of 94. All right. Tell me about this first meeting, how this occurred.

Speaker Well, I kept trying to call this guy like once a month or something, and I would get apparently was his wife usually on the phone and she would say, you know, I could tell she was talking to him and he’d say, no, he does want to talk to you now. Call back or eventually she said, I don’t think he wants to talk to you. So finally, there was some what happened? I got back from Lebanon, I guess, and there was there were some wire service stories that a a paralegal who worked for Brown and Williamson Tobacco had walked out with a box of files, but that he had been gagged and couldn’t talk about it in public. So the little guy might be interesting to meet. And he’s in Louisville and so is white. And so I set up to meet him on my way to New York. And then I called Weygand and I said, I’m going to be in Louisville. And he and I called him at night. And the first I think the night wasn’t well, yeah, I said, I will be in the lobby of the SEAL Back Hotel at 11 o’clock Wednesday, Thursday morning, reading The New York Times if you want to talk the old trick. Well, you know, I went to see Williams first and I saw the documents. Went to the hotel at 11:00. You know, he couldn’t talk, but he can’t really talk and he fits Don’s description of someone who shouldn’t be on TV. And at 11:00, I’m sitting there and this guy shows up.

Speaker So meet you like in Man in distress.

Speaker Very nervous, have coffee, I was concerned before I met him that based on the fact that no one had ever spoken from inside the industry of that close to that rank even, and don’t usually from any corporation that this could be a double agent, that that I might be dealing with somebody who the industry was sending out for, given the amount of time and money they put into litigation and so on, that he could be, in a sense, a ringer, you know, a way to see what the media was up to. So I had already cleared all this with the attorneys. I had documented what I was doing. This was not I was going to size this guy up. So I was also on my guard, you know, so the attorneys at CBS at this point knew what you were doing.

Speaker Oh, yeah.

Speaker Definitely knew what I was doing.

Speaker Comes down. You need him.

Speaker I meet him. We have some coffee and it takes me about half an hour to figure out two things. One, this guy has a lot of things he wants to say, but he’s afraid to say that. And he gave some of the reasons why which were easily checked. And but then he had great expertise. So I handed him 18 pages of these thousand pages of time and said, what does this mean? And he proceeded to tell me this was about Philip Morris so it wouldn’t affect his confidentiality agreement.

Speaker Well, that’s what I wanted to ask you. Did you did you learn at this first meeting that he had a confidentiality agreement that was going to be perhaps problematic for him?

Speaker Well, it was problematic for him. It wasn’t problematic for me. I mean, you know, you meet a government or an FBI agent, an FBI agent has certain this law. I mean, is he or she could be committing a felony by talking to me. But I just happened this morning. I have to talk to an FBI agent. So it’s not an unusual thing for me to be dealing with people who either should not or illegally. It says they cannot talk to me. It didn’t affect me. It made me think about when would he be willing to tell me the story? But I was willing to wait. And more importantly for me at the time, I needed somebody to tell me what are these documents really mean? So you hire him. About a week later, I suggested to him that since he couldn’t talk to us about this, what about working for us as a consultant and reading these documents? Because he’d been taught and I said I got a thousand pages and he was fascinated by the first eighteen. And so he was put in touch through an attorney with our attorneys and our business affairs people, and they negotiated a consulting deal with it.

Speaker So this is right now common practice at CBS at all. The newsmagazine shows you hire a consultant legitimately to help you decipher particular documents.

Speaker Well, and more importantly, in this kind of situation, if you’re me and you’ve been through I live in the 70s, I was through some major libel suits and with magic, with some heavy hitter people, I mean, with lots of assets and lots of attorneys. So and I’ve done a lot of stories at this point involve involving people who can, let’s say, who are the same size as CBS or bigger. And so I know the consequences are possible. And in the hierarchy of television news, the producer walks the plank first. So you’re always looking at your back. Yeah. So from my point of view, he was libel insurance and that’s what I talked to our lawyers about. Right, that all we’re going to do is hire this guy to read the documents, write us a report as an expert, vice president of Research and Development, a major tobacco company.

Speaker And.

Speaker He can look at the script before it goes on the air to vet it for accuracy, to verify, for accuracy only, only. And if we’re sued, he agrees to come forward and testify as to our due diligence.

Speaker Mm hmm. That was the deal. And this goes on quite often. I mean, you’d be crazy if you if you’re working for a news organization that has assets, we wouldn’t put the story on the air. For instance, we put the story on the air. We weren’t sued ABC, but almost simultaneously, they’re spikings. Very often they were sued.

Speaker Right. This became the basis for your first tobacco story up in smoke. Is that correct? And so when what happened? What happened? Oh. When did you then decide to do an on camera interview with Jeffrey White again?

Speaker Well, I always told him, I said, are you ready to talk? Let’s talk over the next. He said, not before March, late March of 95. Would he do an on camera interview? Why that date? Because he still had some relationship with Brown and Williamson that he didn’t want to screw up, supposedly related to his health insurance and so on. So I said, OK, fine, you know, I can wait. You can wait. And I’m used to waiting. Right. So the real negotiations to interview him on camera started really in earnest in April of 95 and ran through early August of 95. And that’s when we did the interview.

Speaker Now, when did might get involved in the story?

Speaker I wrote him a memo, I think early on. Oh, he met Jeffrey Weigand. What? We flew Jeffrey Wigand to New York in March of. 94 to screen the peace with the lawyers there, with gone there, with Phil, with Mike, he thought we were being too easy on it. But what was good, I like that thought we were going to win again. I mean, you know, his expert opinion was that we were being restrained, very responsible, which he said he liked, you know, and I was feeling like, yeah, these people spend 600 million dollars a year on lawyers, so.

Speaker And so Mike admitted that, and every now and then I would send him a memo saying, you know, this guy, we’re still trying to interview him and he’d say, Yeah, right. I’ve been hearing that for, you know, when when’s that going to happen? Right.

Speaker Is everyone happy, everyone’s happy.

Speaker OK. All right, Don Hewitt.

Speaker Well, the forms of television that Don Hewitt has created are part of the collective unconscious of the United States. People, I’m sure, dream in this form. They think in this form and they understand things in that form and for that.

Speaker He should be remembered for sure. He created it.

Speaker He did, absolutely no, he really did.

Speaker Let me take you back to the 18 months after you met Jerry Jeffrey at 18 months after you met Jeffrey Weigand, before you actually did an interview with him in August 19, 1995, 95.

Speaker OK, right. We started in February of 94 and we put him on camera the first week of August. Ninety five.

Speaker That’s right. A lot of things happened in ABC outside of it. Can you fill me in on?

Speaker Well, ABC hadn’t settled when we did the interview with Jeffrey Weigand. There were rumbles before he sat down for the interview. The other rumble was that the Justice Department was going to conduct a criminal investigation of the tobacco executives who had raised their hands and sworn that nicotine was not addictive. That was the final straw for me in terms of getting Jeffrey Weigand on camera, because he was I knew that the federal government knew about him. I knew the FDA knew about it. I knew the Justice Department knew about it. Therefore, it was likely he was going to be a witness before this grand jury. And once he became a witness before the grand jury, the prosecutors, if not the judge, would instruct him that it would be not in his interest to talk about what went on inside the grand jury. So therefore, I thought that Jeffrey Wigand might be lost to us as an on camera interview combined with his intention, which I didn’t realize he was going to be combined with his intention to testify as a defense witness for ABC and that pending lawsuit.

Speaker So I made a deal with Mike’s approval and the approval of our attorneys and Don’s approval. I don’t think Don was directly involved in that. Let’s put this guy on camera, put you on camera, tell us your story. Your wife as well, Mike, wanted to get his wife on, and we will then have a point of departure to start checking out your story. I mean, I sort of had inklings by then of what he had to say, but I didn’t know specifically what he would say on the record. And I realized and knew that I would spend a lot of time trying to vet what he was saying, how do we back it up, et cetera, that check out? Right. And and I’ll do it again.

Speaker And I let this one.

Speaker OK, so it sounds as though you remember when we were we climbed on top of a mountain in Hawaii to shoot this marijuana patch.

Speaker And the piece was like filled with water there, this monsoon. So we had to, like, measure the place.

Speaker OK, we are cool now. We’re all cool. Everyone’s happy. We’re going to back up for one second.

Speaker OK, so what let me just back up because I’d like to get some kind of cut point in here so we don’t have to go back to the beginning.

Speaker Why did we interview? You were concerned that Wagley would be called before the grand jury and we wanted to get him on camera before that happened.

Speaker Yeah, because at that point he would be he could be gagged and this way and told don’t do any interviews with the press, let’s say, by the prosecutors who who he would want to be an ally of. So therefore, we would have it in the can. It was already done. He wasn’t violating any court orders. He wouldn’t.

Speaker Cat’s out of the bag, right? Done is done. On the other hand, we weren’t ready to put him on the air anyway because we knew full well that this guy was going to say things that were damaging potentially to a major corporation.

Speaker Therefore, I needed to do yeah, but therefore I needed to do a lot of background on both him, on the facts, on what could you prove, et cetera.

Speaker And I was looking forward to at the same time, an air date of somewhere in October because ABC was going to go to trial with Philip Morris. And here we had their lead defense witness so we could put them on, let’s say, the Sunday before he testified.

Speaker That was my thinking at the time. Grand Slam. That was the grand plan.

Speaker I did not know that. Two weeks later, his name would appear in print as listed as a witness for ABC. So Cat’s out of the bag there. I did not know that ABC was then going to settle with Philip Morris and pay them off. Creating more tension in the general situation.

Speaker Did you know the dancers can go on the air and apologize to the tobacco company?

Speaker I had no inkling. Well, I should say there were rumors around and some checking that I had done. The serious negotiations were going on. It was hard for me to believe that they would settle ABC. I knew the weakness in their story, but the weakness was filled up by Weygand being their witness. In other words, you could criticize the ABC story substantively by saying that the way in which they talked about the manipulation of the nicotine scientifically was wrong. OK, ok, but. The substance, the gist of their story was true, right, and that combined with the documents that had been delivered in discovery and Wigan’s testimony, would, in my opinion, clearly have convinced anybody that they were manipulating nicotine. It was just the way it was done. Right.

Speaker OK, so next you do the interview. You when do you begin realizing that they are going to be problems?

Speaker Well, first of all, I always knew there was going to be problems. In fact, one of the lawyers reminded me in the middle of all of this that back in February of 1994, when I was briefing them, sending them faxes and briefing that I’m going to meet this guy Weigand, that after I met him on the phone, I said to him, you know, if we ever get this guy really to talk, all hell is going to break loose. Oh, really? Well, that’s because. And this is before the spiking story, before the guys testified because he’s a corporate executive.

Speaker Yeah, I know how many times I have to I would have to emphasize that you’re talking about someone who was privy to the inner workings of a major corporation. These people do not talk, right.

Speaker CIA agents talk. Mafia hit men talk all the time. So.

Speaker If such a person comes forward and talks about what really goes on, what really happened? A great example is and he’s been able to skate on it is Lee Iacocca.

Speaker He was the one who refused to spend a dollar to put a shield on a bolt so there Pinto’s would not explode. That became a huge story, but that story came out because of documents from inside the company litigation and experts from inside both some whistleblowers, but mostly safety experts on the outside. Nobody broke ranks inside Ford Motor Company and Lee Iacocca leaves it out. And his autobiography is an episode in his career. So to get somebody from inside to talk is very unusual.

Speaker I also just want to digress for one second I read that you mentioned I think it would be interesting for you to say this on camera is that when someone from the government does talk, there is protection. When someone from inside a corporation talks, there is no legal protection.

Speaker Well, that’s what I learned a lot more about in the ensuing months. I mean, I knew that this guy was open for possibly four lawsuits. I assumed that if the content of his information showed criminal conduct. Or severe negligence from a civil point of view in terms of his former employer, that he would be protected. What I discovered is, is that because. Was not a defense related company. There were no whistle blower statutes that protected him, even though the public health issue should have been a great issue to protect him. Sorry, you’re sort of guilty first and then you’ve got to prove your innocence.

Speaker At what point did Don screen this interview, get involved in this story?

Speaker His first involvement, as far as I can recall, was in the initial meetings with the general counsel, he hadn’t seen nobody had seen anything because what I had was an interview in the can. I had a rough what I would call a rough working script that I actually put together for one of the meetings and refined it a little bit just to make sure people understood. What are we talking about here? So there wasn’t anything to see until around the first week of October, the end of September. They decided while we were waiting for sort of final judgment from BlackRock, that why not just show people? Now, what it is and what happened. People saw it. Govardhan, Mike, Don and Mike thought it was great, I think Don was jumping around saying Pulitzer Prize or something, you know, Don assume I don’t know, Don. Tell me what he was saying, what he saw. He saw the sound bites and he got all excited and he sort of like jumps up from his seat and says, Pulitzer Prize. Pulitzer Prize. You know, I mean, you know, if you’ve been around long enough, you know that every pretty good story you do is a prize winning best story we’ve ever put on the air.

Speaker So you have a grain of salt about it. But I knew it was pretty good because as I said, you can have documents, you can have experts. But the insider is what makes television the face. The person saying this is what happened. And. Here’s the guy.

Speaker OK, so you screen it for the brass at 60 Minutes, when did the final judgment come in that way? Waggons interview cannot be aired next. Oh, we have to make that again. Probably the most important question of this entire interview.

Speaker Frivolousness do everything. Ifti, the decision come in?

Speaker Well, not you know, there’s a lot of this has been published. But let’s let’s assume it hasn’t just been basically what we were dealing with for a period of about three or four weeks in its formal sense was the opinion of counsel.

Speaker Judges, lawyers.

Speaker I don’t care if it’s the general counsel or is it just a lawyer for the next day after the screening, I remember asking the question on the phone. I had to call him to Eric over. And I said, look, the opinion is that this is too much liability, et cetera, et cetera. Tortious interference, wonderful concept. And what’s your decision?

Speaker Now now you’re jumping just a little bit ahead of my story here.

Speaker You say you have been talking to the counsel for the general counsel came to I was summoned to Blakroc on my way to London. I was on my way to London to check out some of the British side of what Weigert was talking about and had already set up a bunch of things over there. This is September. Yeah, early September, right after Labor Day. And I was summoned to BlackRock for the first time in my 14 years at CBS. I went to the building and in a sense was downloaded by our in-house lawyers who were the ones we normally deal with on everything related to the case. So it was kind of funny because there were the guys who I told everything all the way along the line. So they had memos, they knew, they remembered and so on. And we just sort of relived the process.

Speaker And it was at that meeting that I first heard the concept of tortious interference and told that there was some problem with this guy speaking at all and for very for the general information as to what tortious interferences, I would say go and talk to an attorney. That’s what I started doing. I started calling lawyers and I was told that.

Speaker After I learn how to spell it, that it tortious interference apparently means that what you do as a third party is interfere in a contract that someone has with someone else.

Speaker And in this instance, having spoken to an attorney, what I think I understand it to me is that 60 Minutes relationship with Wagin in terms of getting him or influencing him or having him talk on camera, create a situation where he broke his confidentiality agreement, is that correct?

Speaker Right. That we induced him in some fashion to ignore his contractual relationship with Brown and Williamson and speak to us? Right. OK, so now you’re told about this, but everybody I talked to when I researched it or started making calls about it said that where it’s used is where you get some financial or business profit from helping that person break their contract. And I said, well, that can’t be me. I don’t get paid anymore. For and for all I can tell, we’re going to lose money on the deal. So, you know, all I’m interested in is did they do anything, the damage to public health, where they lying to the public? I don’t care how they make cigarettes or what kind of deals they’re involved in to make cigarettes. That’s not what this was about. This was about the public health.

Speaker Do they tell you to stop the story at this point?

Speaker They told me to wait. And I waited three days or so and we had a bigger meeting, that’s where it was explained to Don and Mike and Phil by the general council. What? But what this tortious interference was and how severe the situation was, and by this point, Don had seen the interviews. No, he hadn’t seen the only thing anybody had seen was I had this rough script that had white man’s name in it, you know, which was a rough assembly. And I remember Mike lost a copy of it on the way to the meeting. He said he left it in the bathroom, I think it was. Or something like that.

Speaker Oh, God.

Speaker So I don’t know, it may have got out in the end because there were like only eight copies or something.

Speaker Maybe you took it up. Yeah. So you now screen it for Don. You’ve heard about what the problems legally might be.

Speaker Oh, we’ve definitely heard the problems and what happens the next day. Well, there was, which I didn’t realize, but the general counsel had gone to another council outside at the request of our other lawyers to get an independent view of what I didn’t realize is the guy that she went to is a guy who represents the magazine and billboard industry and fighting the ban on tobacco ads.

Speaker But be that as it may, an independent review and we get the opinion back that can’t do it to potentially the whole broadcasting division will wind up being owned by Brown and James. OK, so then I said to myself, well, this is just coming from lawyers, what does the president of the news division have to say? And I called him up and he said, Eric over. Yeah, Eric over. And he said the corporation will not risk its assets on this story and story.

Speaker What is dancing? How much?

Speaker So what are you supposed to do now?

Speaker I went home.

Speaker And, well, you you want my whole personal story, right? Yes, well, some of it I’ll tell you today and some of it I’m not going to tell you today. Basically. There’s a serious problem here, which I laid out to Mike in very emphatic detail. I came into the business with a name and I had promised myself that I would leave with my name intact.

Speaker I had been ordered by the general counsel and now the president of the news division to cease and desist, and I think Phil Scheffler told me in a booming voice one day, stop everything you’re doing on this story.

Speaker There’s a serious problem with that, because the motivation for stopping was a corporate motivation that disregarded. The fact that I had told this guy that he could trust me. And he could trust CBS News. Furthermore, it’s our business allegedly to try and do stories that are in the public interest, no matter how difficult they are. So I remember telling me this is not just killing a story, Mike. This has to do with who I am and what this business is all about, and it isn’t going to just end here. Pretty difficult moment. Well, I mean, you know, that’s more of my story you’re doing Don’s story.

Speaker No, I’m doing part of the story, too. So.

Speaker So, you know, a variety of things happened, what it might say.

Speaker Well, he sort of understood, but.

Speaker You know, I think Don and Mike were uncomfortable with what had happened, I mean, Don told me that that was the first time and then 48 years of the company that the general counsel had ever come to the news division physically was always done through. The president of the news division was sort of the buffer. You know, it was bad news that came through that way. So therefore, there was the appearance of the insulation between the corporate side and the news side. I should say to begin with, that all of the facts, the salting arrangement, all the stuff was all laid out on the table. Everybody knew everything who was in this group. Now, we were not allowed to tell anyone else what was going on, last one, because the the understanding I had now here I get into a little bit of difficulty because I don’t know whether I’m allowed to talk about with attorney client related matters. So there is no litigation currently pending. But to do it in a kind of imagine that if the theory is that we have already cautiously interfered. Right. If it becomes public that we did that right, then we’re challenging them to sue. I see. OK, so there’s a reason to keep this all under wraps. The advice was that no one have any further contact with Wangan. And in fact, in between the initial meeting and the final decision and like the 2nd of October on my way, I’d gone back to California for a while and I said to the lawyers, who I normally deal with, I want I can’t go to London. It’s not. It’s not a. Absolute decision yet that we can’t do this story, so on the way back, I want to stop in Louisville and debrief this guy some more, find out more, get more information, then I’ll continue on back. Is that OK? And he had been at these meetings and he said, yeah, sure, why not go down alone? So I go to Louisville, I go to his house. By then I become very friendly with his children, his two wonderful daughters. And I’m kind of like into pictograms, you know, with little kids, you know, so like a faxing pictograms back and forth. That’s an insidious inducement here. And they want me to stay for dinner. A friend of the family’s at this point. Well, I had to be I mean, I’d met with them a bunch of times. We’d been through some severe emotional stresses, let’s say, in the family discussion about whether to do this or not.

Speaker Anyway, so I’m sitting in the backyard with Weigand and mid-September and the phone rings in the house and they bring out a portable phone and it’s one of the attorneys and he’s saying to me and he sounds like he’s got a gun to his head or something, and he’s saying to me, you have to get out of the house.

Speaker Stop talking to him, so I take the phone and walk around the backyard so they can hear me and I say, look, I won’t talk to him anymore about anything related to Brown and Williamson or the story, but I’m not leaving.

Speaker You know, they just invited me to dinner. I’m just not going to walk out the door, you know, I mean, come on. So that’s what I did. I had dinner and then I left.

Speaker So you never told him about anything?

Speaker Well, I couldn’t I didn’t feel I could tell him on the one hand, because it’s an internal CBS matter what the deliberations were. On the other hand, I had to sit there and realize that this guy that at least our own lawyers were saying that he was liable for breach of contract and when we knew that, but that we weren’t going to be anywhere near this guy, you know, and that I’m supposed to give him up. Now, that’s worth, you know, that that happened before the final decision, after the final decision, that also happened before you even screened it for Don. Yeah. Were you able to turn them around to some degree in that interim? No, no. Well, I mean, I think people didn’t really thought maybe this possibility is going to run, but or, you know, that we could go forward anywhere. I mean, in my book, you have to understand there where I was pretty shocked about this, is that not that there would be interference. I expected that when we screened the story, the normal process, there would be objections or God knows what would happen. I’ve seen strange things happen, but I was expecting that it always happens in these situations, something you don’t expect. What I found extraordinary was that the general counsel was coming into the news division in the middle of the reporting process.

Speaker Hmm. And had come up with this concept out of thin air.

Speaker Which is almost like you said, it was like a new rule.

Speaker Well, nobody never been applied, apparently, to anything related to the First Amendment that anyone could understand. With no precedence. You know, it was Larry Tisch got sued for tortious interference in the Pennzoil Texaco takeover or something. I mean, that’s where, you know, it’s one sports team might, you know, get disciplined by the league for interfering with the contract between a player and an owner of another team. You know, that’s.

Speaker This didn’t make sense to me. So now you’ve discovered that the story is going to be. Killed at this point, now come back to California at this point, what is Y.A.?

Speaker I asked Mike to call him, you didn’t call yourself, not at first. Now I called I talked to him afterwards. I did not have. Hard to call him after all of this and say, hey, we can explain without. Really being negative about the company.

Speaker What had happened? I talked to him afterwards.

Speaker Because you at this point had a relationship with him?

Speaker Well, I mean, you know, he wasn’t my best friend. He was a somebody who wanted to tell a story, which I thought was important, who I encouraged to tell the story.

Speaker Yeah.

Speaker I would say it was more than a relationship, I had a responsibility, absolutely, which I was being told not to talk to him anymore.

Speaker And you’d given this man your word. I mean.

Speaker Well, more of those were my word. I said to him, hey, it’s an important story. We’ll run the story he wanted to do with 60 Minutes because it’s 60 Minutes. You know, where is it going to go? Where else would he go with a story like that?

Speaker I mean, it’s one of those real instances where you could say, trust me, and you really felt that he could trust you.

Speaker Where’s my little bumper sticker? Trust me, I’m a reporter and. Now, I’m a producer, by the way, we’re not reporting. Yeah, did you have any contact with Don during this interim? Sure, plenty. And what was dancing?

Speaker He was trying. I think he was trying to.

Speaker I think he was getting a little irritated at different times with me and saying, I don’t understand this and why can’t we do this? And. You know, that routine, I was not happy with it. I think he was also trying to figure out a way to straddle. He didn’t like the idea, didn’t like the idea that he couldn’t run the story or go forward, that he was being stopped. On the one hand, he didn’t like that. On the other hand, he wasn’t about to step forward and say, hey, we’re going to go forward on this. And you guys.

Speaker Nobody said that you guys try and stop us.

Speaker He said something that was Walter Cronkite said he could have done well later on when this all came out.

Speaker I think Cronkite had said that they should have all resigned, meaning Mike and Don.

Speaker Did that ever come up as a possibility?

Speaker I think Mike thought about it occasionally.

Speaker Do you think there is something Don could have done?

Speaker Sure, what? Exactly what I said.

Speaker But that’s my opinion, I mean, my opinion is if I had gotten up and said. I’m going to go public and blow the whistle. I’ll get fired, why gets discredited, we’ve got two dead bodies, no story. You know, I think I was disappointed that people didn’t say, look, this is outrageous. We’re not even talking about putting it on the air yet, we’re talking about reporting it.

Speaker Do you think they’re done? I mean, could have said I’ll resign and one.

Speaker But that’s my opinion, you know, I’m not. Risking his life, basically.

Speaker Could 60 Minutes have said we’re not going to go on the air at all that night?

Speaker Well, it wasn’t scheduled, I mean, any night, I don’t know, I mean, you know, there are a lot of possibilities about what could have happened, didn’t.

Speaker Journal journalism, you don’t get a license to practice journalism. Anyone can practice journalism. Yes. CBS 60 Minutes, New York Times doesn’t give you a license to practice journalism. Right. In a sense, it’s a self-made career for everyone, even if you’re an institution, whatever the pressures are. And in this case. The company that owned CBS News was telling me directly or indirectly, we don’t care what you think about news or journalism, we care about our business interests. OK. Yeah, and a real person’s life was in the family was in the balance. And they were saying, we don’t care about this person. Who you were dealing with and what the consequences may be for him and his family, because the consequences potentially are so catastrophic for us. We can’t even conceive of it, in fact, not one word was mentioned about what about him, who’s going to protect him when he gets sued, especially we couldn’t protect him on a breach of contract suit. But the idea that he was on 60 Minutes would give him some imprimatur, some some self-worth and some standing if his information turned out to be correct, which we were in the process of checking. So that was did turn out to be correct? Yeah, the the just the basics. You know, he had some eventually, you know, we changed some things in the interview before it aired.

Speaker You know, we researched everything the way we normally do. I told the attorneys at one point when we were going to put it on the air, they look, you know, I would like more time to to research now that we can put it on. I really like the time to check it out, but I realize now we don’t. But you guys understand we’re going to be able to. Only do so much. Yeah. And I think that that was the bottom line issue and is the bottom line issue related to why can’t I mean, we operate, we we go we meaning 60 Minutes or any program, it’s on the air essentially with the approval of the people of the United States.

Speaker We get the use of the airwaves. And for that, we’re supposed to do something that’s socially responsible. And this instance was a was a clear example where we were told, well, maybe the public health involved, maybe criminal behavior is involved.

Speaker Sorry.

Speaker You got a censored version of the story on air, November 12th, 95.

Speaker Mm hmm. How did that come about? How did you get that? Well, it’s a very interesting footnote. Yeah, I think that.

Speaker A story appeared in The Wall Street Journal in the middle of October, two weeks after the story was killed, which essentially had in it part of our interview, which had to do with the use of chemistry and ammonia to manipulate the effect of nicotine and the sort of advanced scientific aspects of how they produced this product. This was in essence, this was the gem that Jeffrey Weigand had in his head. It’s the information that Jeffrey Weigand gave to David Kessler in May of 1994 and before. It’s the information that David Kessler, the head of the Food and Drug Administration, has subsequently agreed and said in public that when he appeared before Congress in June of 1994 to testify about tobacco and he testified at that time about ammonia and impact enhancement, that all that information came from Jeffrey White. And that was the essential. What’s a fact? We had that ABC didn’t have an inspiring story. That was our story. Right. OK, there it is in The Wall Street Journal on the front page. And I think two weeks after our story is basically put on the shelf. And I think that stirred Don up.

Speaker And Mike, I think I got depressed.