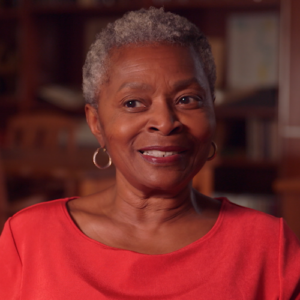

Interviewer: Margo, thanks for doing the interview.

Margo Jefferson: I’m glad to. Thanks for inviting me.

Interviewer: Tell us about your first memories of Sammy Davis Jr. When you first. What do you remember first about Sammy Davis Jr?

Margo Jefferson: I remember first about Sammy Davis Jr, seeing him on television. And at that time it would have been the fifties. He was with his father and uncle with Sammy Davis Jr and the Will Mastin Trio. My parents, I remember that my parents had seen him in New York in a nightclub and they were very, very, very excited. It was thrilling. In those days, whenever a black performer appeared on a flight, there would have been a variety show always. Milton Berle, Ed Sullivan, whatever. And he was on the rise, the dynamic, young talent. I was very excited by him. It was you know, first it was it was, of course, this very lovely voice, the dancing, the pure dynamism. Later, I remember the little later the imitations were terribly, terribly exciting because he was crossing racial lines. You know, he was imitating white performers. And that, you know, felt like an incredible sleight of hand and kind of victory. What I also remember, and I must have come from my parents is they were not entirely pleased that he was with the Will Mastin Trio. They felt that these two honorable elderly men didn’t quite belong on the stage with him anymore, that he was they appreciated that he was being loyal to them, but they felt the time has come to retire them. You take good care of them, that you appear on your own now.

Interviewer: Because they seem to be just like supporting.

Margo Jefferson: An old and old world, old world, black vaudevillians. And he was a kind of new black star entertainer.

Interviewer: And tell me about that. What was that old world vaudevillian world like? Do you remember your parents?

Margo Jefferson: You know, my parents talked somewhat about it with actually great effect affection. My mother grew up in Chicago, so the old black vaudeville circuit was very much there. The Regal Theater was a big, big, big thing. But Chicago was also a center of more sophisticated jazz clubs. So you would have you could have comedy, but you. So she grew up with both. And I think she and many of her friends felt I know less about my father because he was in California. And I think she and many of her friends felt that at a certain point, you know, you almost outgrow a kind of bumptious black vaudeville comedy. I know comedians named Garbage. Yet you still enjoy it? Definitely, yes. Sure. Well, mother always remained loyal to mom’s. Okay. There were always some you. But that. That. And this is true of white vaudeville to the second stringers. You know, in in vaudeville, as you moved into nightclubs or movies, you know, they seemed a little countrified. They made the form seem old fashioned. Right.

Interviewer: Very good point. What’s also interesting, too, is that think about before World War Two, we had all these black entertainers. I mean, you know, somebody like Nat King Cole, who was with Straight Loving Fly, right?

Margo Jefferson: Yeah. Yes, yes, yes. Great song. That trio, those were his some great around.

Interviewer: But they were focused mostly on the black.

Margo Jefferson: Absolutely.

Interviewer: What happened after World War Two? Are black entertainers start to reach a wider audience. A white audience. What do you think that changed start to come about?

Margo Jefferson: Now, I’m going to tell you frankly, just on the economic I don’t really I look tried to look up historically exactly what was happening. Well, you know, they were moving into there was this push from blacks and progressive whites. After World War Two, there was some sense. Hello, more rights. You know, we fought in the war. It was a war against, among other things, bigotry, you know, racial and ethnic prejudice, murderous. Let’s make some advances here. So it seems that the nightclub and hotel scene began to open up more and that offered major opportunities. Then, as we moved into the late forties and fifties, television began. To offer.

Interviewer: Exposure. I grew up in the fifties and sixties, and just like you watching, you know, Ed Sullivan Show, a milton Berle show and seeing some of the comedy here, what, Nat.

Margo Jefferson: Cole or Lena Horne? Dorothy Dandridge.

Interviewer: It’s an amazing thing as a young black man to see these black performers on television. I mean, again, for you was that it was like such a thrill that our people were on the screen.

Margo Jefferson: To see black performers on television was it was as if and I think this really happened, everybody would phone everybody else and say, you know, Sammy Davis Jr or Lena was going to be on the Colgate outrage tonight. These were some of the only places where we were visible as part of an exciting, thrilling, you know, scene. The entertainments that every American admired, looked up to, worshiped, wanted to be part of I. We were not deferred to in any other way. And despite the fact that these performers were not deferred to offstage, you know, when you walk on now to the set and all eyes are on you now and the orchestra is behind you, or you and your cool trio are there, you know, that’s starpower.

Interviewer: Made it feels made us feel very special.

Margo Jefferson: It made us feel yes. And by feeling special, we could for a time feel equal. Good points. Yeah.

Interviewer: How would you compare Sammy to two of the other reigning symbols that were on television at that time and in the recording studios? Nat Cole and Louis Armstrong. How would you.

Margo Jefferson: Compare? Oh, it’s interesting to think about Sammy in in comparison to Nat and Louis. Well, Louie, Louie, Louis was an earlier generation. He had been born earlier and he was he’d made this interesting bargain, a very good one, between being a an enormously successful popular entertainer and a jazz and remaining a jazz musician. Yes. Some of the bebop musicians, some of the boppers, you know, made fun of him. But he was still he was a still real jazz musician. He had become a kind of almost the the benevolent patriarch of black male entertainment. But he in some ways also seemed, however lovable. And all the black people I knew did love him. He still was a he was old world and a kind of, you know, glorious way. Nat King Cole, you know, with that elegant trio, you know, work behind him. When he moved into popular song, he he was very sly and winning. And he insinuated himself into our sight and our ears and eyes as a performer, you know, very canny, subtle. You can hear it in the piano as well as and playful, but quietly so as well as in the singing. I’m leaving out the sort of syrupy ballads. Sammy Davis Jr burst through its on the comment You will pay you. I’m landing, I’m spinning, I’m dancing, I’m doing imitations. You will pay attention to me at every moment.

Interviewer: That’s fascinated me because, you know, when you think about it, I always think of that King Cole. So, so.

Margo Jefferson: Oh.

Interviewer: That family so aggressive.

Margo Jefferson: That’s right. That’s exactly right. Nat was suave and smooth. You got it perfectly. And Sammy was Mr. Dynamic aggression, right?

Interviewer: Yeah. But, you know, for me, Armstrong, who I, I, you know, quite honestly, I didn’t think I started to appreciate, so I became an adult.

Margo Jefferson: Okay, I understand that, but a little bit of an embarrassment.

Interviewer: Handkerchief.

Margo Jefferson: Yeah, got it. Oh, the wiping of the.

Interviewer: Yeah, it was a little too much for me, but Sammy was slick and cool and aggressive, and that was, you know, every cool to me.

Margo Jefferson: Yes, that one Sammy and, and that were the younger generation. They really were. You know, they had a kind of urbanity out there and they represented in some ways they were not bop musicians, but they in some ways partook of that saying, well, actually, I’m I take this back. Nat Cole was in his early days involved in BOP but they they partook of some of that same we are a new breed energy and forcefulness that we were seeing in in bop musicians.

Interviewer: What do you what do you remember as a young black woman thing that all the news articles and and publicity that Sammy Davis was getting for being associated with White. Man romantically linked with white women like Kim Novak. Many of them.

Margo Jefferson: Are reaction to Sammy and his interracial romances. Now, this was largely in the late fifties, early sixties. All right. So this can’t really be Sammy and his interracial romances can’t really be separated from Sammy and the Rat Pack. Right. It was exciting that Sammy was running. It seemed so to me, with all of these glamorous Hollywood male stars, it felt like he had one entry initially in those early years to a very cool fraternity. And publicly, you really didn’t see black and white performers seeming to be on equal jovial playboy status, you know. It was also all of them kind of in that Playboy magazine mystique, which still seemed glamorous. They were also the white men known in front of the camera to be liberals, basically. Now, as it turns out, now we move to interracial romances. Now we know that at least Frank Sinatra was urged to please tell Sammy to back off. These women like Novak or Mai Britt. Now, was it my bet that they that the president gave the warning.

Interviewer: And once sent the disinvited Sammy to the.

Margo Jefferson: And that was it, okay. I at the time thought that actually it was pretty exciting. And again, I was a little high school girl and it was forbidden. And Dorothy Dandridge had a white husband. Lena Horne had a white husband. So I wasn’t. Eartha KITT. So I wasn’t feeling, you know, deprived in terms of identification with people who had the right to do what they wanted. So I found it very intriguing. I can remember articles in Ebony. Yes, Sammy and my and she was also my was Swedish. So there was that European American cross cross-cultural. You know, that was to me as a young girl. Interesting.

Interviewer: Oh, gee.

Margo Jefferson: Yeah. Intriguing.

Interviewer: Exciting about the German reactions when he embraced Judaism.

Margo Jefferson: Now, what year did Sammy Davis Jr.

Interviewer: Embrace Judaism, this car accident?

Margo Jefferson: So that would have been in the fifth. Okay. Now, at the time when, you know, again, I was I was a girl. But in those early years when Sammy embraced Judaism, there were a lot of alliances in terms of liberal progressive race politics between blacks and Jews. So, you know, if one if I was surprised, which I’m sure I was, it seemed okay, you know. Sure. All right. This in some way sealed the deal. Later, he would joke so compulsively about I belong to two groups and he’d sort of tell, you know, he would clown and sort of fake Yiddish and he’d clown around and sort of fake or very theatrically extreme blackness, too. Yeah. And you’d kind of go, Oh, but, you know, it became an eye rolling, double edged schtick later.

Interviewer: Let me ask you this question. I mean, so here’s a guy who’s having these relationships with white women. He becomes enamored with Jewish religion. You know, he’s hanging out with the Rat Pack. The this we use makes Sammy Davis seem the last very provocative figure at that time, someone that was such a real maverick with the jazz thing. That was par for the course in terms of an entertainer.

Margo Jefferson: Well, I think I have to distinguish between the early sixties, late fifties and early sixties and the political changes. Militant, more militant, black power, all of that in the so late fifties, early sixties. He was something of a maverick in certainly, if you compare them to even the big stars among jazz musicians. You know, Duke Ellington wasn’t doing that. Neither was Count Basie. They seemed to be, even though they had mass white audiences and we knew they had we assumed they had white friends. They still seemed to be living in a universe that was more black. But in this. World of show business. You know, the theater, musical theater, theater, theater, the nightclub circuit, cabaret. This was a this was a little more to be expected. What’s my sense? Now, I remember an article that appeared about Eartha KITT, who also moved in very integrated circles. It appeared in Ebony magazine and was a cover story, I think. And the headline was something like Why, you know, Negroes Don’t Like or Suspicious of Eartha KITT. And when you read the article, which I went back to read recently, it was basically saying, a lot of Negroes don’t like that she chooses to live in an entirely integrated and in some ways predominately white world. They feel she’s turning her back on them. But the article concluded, you know, with Ebony sort of taking the official editorial voice for the community. But, you know, in fact, we need to understand that she can do what she wants, that, you know, she, of course, you know, cares about her people, etc., etc.. So I think that with Sammy and Eartha, partly because I was living in too semi segregated worlds that at certain points integrated, I had a black and a white social life and to some extent they overlap. To me, in those early years, it still seemed, yeah, interesting that he was claiming taking license, you know, and that he had every right to in some ways maybe it was the socially equivalent to. Yeah I couldn’t imitate Jimmy Cagney. You know you can look at me and here I am with this black face and I sound like Cary Grant, and you have to laugh because for a moment, I fooled you’re taking liberties.

Interviewer: That’s very complex stuff, you know, because that that whole notion of the duality of who we are as a people, you know, going back to Dubois.

Margo Jefferson: Yes, yes, yes.

Interviewer: I used to never.

Margo Jefferson: Leave, I think. Well, I think in terms of the duality, I think the balance really collapsed with with Sammy Davis Jr in terms of his public behaviors, manners, style. As the years went on, he began to seem to me it’s probably by the mid sixties now I know he was at the March on Washington, etc., etc. He began to seem more desperate to be, you know, in the company of white people, more clownish in terms, again, of the the playing, the theatrical izing of a kind of, you know, trope of black soulfulness, of getting down, you know, in this very broad way. And some of it did seem as if it was done for the entertainment. Okay, now here is my black he was my funky voice. You know, even the way on talk shows and whenever someone the host told a mildly funny joke, Sammy would do this black thing that I loved, but he turned it into a kind of caricature. He would get up, run across the room, bouncing to the wall, kind of fall down, you know? Oh, man, that is so funny. Then run back and sit down. Yeah. Oh.

Interviewer: Yeah. So that’s the perspective he had going.

Margo Jefferson: Oh he was go I felt. And I was not alone. He was going overboard, he was pushing it, he was getting ingratiating and a little desperate.

Interviewer: Desperate for, for Black Connection. Desperate.

Margo Jefferson: I would say it felt like desperation for in terms of, for example, the Rat Pack. Increasingly when you saw them perform together, what you saw and again, that was as the years progressed, what you often saw was Sammy, not as the equal swinger, but as the butt of the race joke. Sometimes it was a black and Jewish joke, sometimes it was just a race joke. But, you know, he had to play his part. It was as if in order to get those moments where he was singing and swinging, you know, with them, you know, like what? He was a top entertainer, you know, in the trade off for those was playing the black for.

Interviewer: The good answer. Let’s look at what was going on. You know, So we both grew up in the fifties. We both grew up with Sammy and Sydney.

Margo Jefferson: You know, Sydney and Harry Belafonte.

Interviewer: No place in the sun, right?

Margo Jefferson: Oh, my God.

Interviewer: In the sixties. Come along. And, you know, I remember as a young man listening to Floyd Patterson fight Ali on the radio was Cassius Clay. He was Ali.

Margo Jefferson: Yeah.

Interviewer: And I was rooting for Floyd. Hate to be Muhammad Ali.

Margo Jefferson: Oh, interesting.

Interviewer: Because I thought that Ali was too aggressive, too outrageous.

Margo Jefferson: Right.

Interviewer: And Panthers and the whole black.

Margo Jefferson: Power.

Interviewer: Power. What happened to I had to tell you, this is the sixties start to evolve. You know, the James Brown in Sydney and Harry and Sammy with Sammy fit into that sort of.

Margo Jefferson: Well, what you’re really talking about as the sixties progress and Black Power Rises, you’re talking particularly about images of black masculinity with these particular performers. This cluster of black male symbols and all of them were shifting somewhat. Belafonte was shifting from the very handsome, always dignified, but very handsome and sexy singer, entertainer, you know, to the kind of more dignified, you know, clearly wearing his race. Pride and militants, Sidney Poitier in the mid-sixties, the Oscar for Lilies of the Field. So Sidney Poitier in the early sixties, well, let’s say from The Defiant Ones, which is late fifties, right through Lilies of the Field mid-Sixties, Oscar, he is able in those early films like The Defiant Ones or Blackboard Jungle to show fascinatingly flashes of, you know, anger and resentment power. And then the plot requires that those flashes be submerged and that into a kind of generosity, a kind of peacemaker, peacemaking initiative, if you will, that’s going to change somewhat in the later sixties. Nat Cole pretty much remains Nat Cole, which is interesting, but he has the TV show, which is a real step forward. But it’s it’s still within those fifties sixties integration and entertainment frames. Now, James Brown represents the the onslaught really for Tin Pan Alley. You know, performers, the Great American Songbook, black and white jazz. James Brown represents the onslaught of R&B and rock and roll, which threatened actually all of them and threatened to be, you know, the careers and the image to some extent of all of them. R&B and then followed by soul music, captured the young black audience. They were all at risk. But at least a movie actor like Sidney Poitier still had, you know, a movie structure to work with. But they were all at risk of becoming old fashioned or world almost irrelevant.

Interviewer: And with Sammy fit into this.

Margo Jefferson: Sammy Sammy has an overpowering will to to keep up. I actually traced that back to 1906, where Sammy fits into this emerging militant masculinity. I think he starts it when he does Golden Boy in 64. You know, again, very mixed narrative motives, etc.. But it it was a kind of dare. I see that is his way of really, you know, bringing his version of manliness to the civil rights movement. Then as we move into the late sixties. I think he’s a little he’s he’s he’s somewhat he’s a little lost, is a little threatened. He doesn’t does he have a hit? I don’t think he has any kind of hit in the late sixties. So, you know, it’s nightclubs, it’s performances. Again, it’s this that it’s at that point also that the public persona of Sammy with the Rat Pack is starting to fray. And many of us saw it, you know, because I think the tension, the anxiety, the submerged, you know, power clashes that must have been there with all of these men for years, they are being foregrounded, you know, as race politics get more vehement, as you know, and as black male voices get more. And so the pressure is coming on, all of them, not just on Sammy Davis Jr, but on Sinatra, on Martin. And I think that’s partly why you see these kind of painful, almost embarrassed, you know, sometimes. Painful, shameful and often embarrassing, really little explosions, almost of hostility. The vehicle may be.

Interviewer: You know, but he also did that movie, a man called Adam.

Margo Jefferson: That’s right.

Interviewer: Which is in its own way, a sort of a presentation of a really angry black.

Margo Jefferson: You are right. So if you go from gold. Okay, so, Sammy, working with black anger. If you go from Golden Boy in 64, isn’t that 64? Yes. To a man called Adam. You know, this is the this is the Sammy who is trying to follow up on the legacy of the March on Washington, which in the in the light or shadow of the Black Panthers and Malcolm X, it can look pretty tame, but it wasn’t, you know, it was big. So he is he is trying to follow up and cement his own his own place in this stuff.

Interviewer: I mean, I think are doing all this research and say I mean.

Margo Jefferson: Yeah.

Interviewer: You know, when you research some of these these people that I’ve been involved with, like Sammy the Marvin Gaye, you sort of see your own. So I see this as a struggling to find a grab on to a sense of identity. You know, who.

Margo Jefferson: That that is, that is yours, but that also keeps you relevant, you know, in show business and in the business of staying important to your people, to black people, but also particularly for Sammy, you know, Marvin Gaye, James Brown had a had a real black constituency because they were R&B and soul musicians. Sammy did not have the same black constituency, and he did not have a young constituency that was busy buying his records. And they’re not going to pay to go into these nightclubs. So he’s relegated in a way to an earlier generation.

Interviewer: So you see him as an old school entertainment.

Margo Jefferson: I don’t I see Sammy is an old school entertainer in a way that is not pejorative when he’s at his best. You know, I, I really honor that tradition whereby, you know, a young kid is, you know, learning his steps, his his gestures, his routines, his dance, grabbed his singing from terrific older performers in vaudeville. You know, he is taking on taking up mastering, you know, a number of forms. He could be a comic. He could be a very credit creditable, credible, creditable, credible, credible, dramatic actor. He was a very good singer. And as it turns out, I’m it. We always knew he was a good dancer. But I find it interesting that in those later lat in the last years of his life, he reclaimed his ties to younger generations, going from Gregory Hines to Michael Jackson largely through these dance skills. The movie Tap as well, where he was placed very artfully between these great old hoofers who were seen as pure in a certain way because they had remained, you know, black tap masters who were not, you know, spreading out into this larger, possibly diluting white world placed between and among them, and then placed with Gregory Hines.

Interviewer: And a young Savion.

Margo Jefferson: And the young Savion as well. So between this trio, Hines, Michael Jackson Savion he very intriguingly restored that that his place in this lineage.

Interviewer: Absolutely agree with you. It’s interesting to the sort of fascinating you think about it. Sammy Davis started as a young man playing Rufus Jones, the president.

Margo Jefferson: With Ava Walters.

Interviewer: Michael Jackson.

Margo Jefferson: That’s right.

Interviewer: There’s so many jazz generation.

Margo Jefferson: It what? Well, being a child star is a huge weight. And when I think about Sammy Davis Jr and say someone as skilled in his way, which was Michael Jackson, you know, I, I am so aware of the what’s so honorable about how hard they worked, how gifted they were, how much they mastered the cost emotionally and physically is enormous. And I think it’s fair to say that probably we were witnessing at various moments in Sammy’s career when he was acting up and acting out and seemed to be almost hysterical, you know, in his need to please get black audience, get a white audience. I don’t know. We were seeing, you know, almost forms of functional nervous breakdowns, as I think we saw with Michael Jackson to.

Interviewer: Let me ask you in a broader perspective. So what do you say about a career like Sammy Davis, as that could go from Ethel Waters all the way to Michael Jackson, that he could span such a breadth of time and people?

Margo Jefferson: Well, it says that there was a core of craft, of charisma, of of of honor in the sense that a performer knows not just how to peddle and shell his or her art, but knows how to draw on the best of it and honor it internally, which always shows on stage or screen. He he did at his best moment, have that. And he had enormous resources. He didn’t always use them, but he had them and he still could.

Interviewer: And he was able to do that from decade. A decade.

Margo Jefferson: It it you know, there were bad decades, but he was able to keep renewing that at moments and in an important moment. So let’s say he began when was Rufus Jones? 434. Okay. So you’ve got a couple several really good decades, you know, the thirties, the forties, the fifties, the early to mid sixties. Things start really slipping in me in the seventies. You know, there’s Candyman. There’s also the attempt to kind of reclaim, I think, his legacy, his lineage as a certain kind of entertainer who had to make internal as well as external sacrifices, but also I think trying in some strange way to to reach out to young white and black audiences. There was the Mr. Bojangles number, which I now find moving, which at the time he did it, I found somewhat embarrassing.

Interviewer: Why.

Margo Jefferson: I didn’t like the song, particularly. For one thing, I felt it was excess deaths of late, a little patronizingly sentimental, and I think I probably still do think feel that. But, you know, performers can work with that. So, yes, at the time I thought, oh God, it felt like a throwback to oh, oh, the the pathos of didn’t have to be a black performer, but with the name Bojangles, of course, you’re assuming it was a slightly unearned, you know, the pathos of an old black trooper who ultimately is something of a victim there. But now when I see it, I find it more complicated and interesting because I think it I think the song says a great deal about how he saw himself and how he felt he’d had to live and even some determination to keep going. I think there’s that as well as a kind of excessively eager to please. Objection.

Interviewer: It’s a good answer because as I think the song is, it’s because of Sam. He’s been gone for so many years. And now when you hear the song, it has it has a kind of resonance and gravity.

Margo Jefferson: It didn’t before. And maybe, you know, sometimes performers have to die for that to happen, but maybe it was there then. And we simply you know, there were too many other complicating factors.

Interviewer: So you’ve you’ve you’ve already you’ve already said this. I want to ask you again, do you think that Sammy really became out of step with his times?

Margo Jefferson: He came back. He came out and I think that Sammy fell out of step with the times at certain crucial points decades. The the embrace of Nixon was what, year? 19. He okay Sammy Davis Jr embrace Nixon in 1972. That was the same year as candyman. The when you look at this now. Nixon to me, looks as, you know, ridiculous as Sammy looks the under the water. What an absurd mismatch. But it seems to me from Sammy Davis Jr was not a fool from the point of view of a canny what should be a canny black entertainer. You don’t hug Richard Nixon, don’t rush up behind him and hug him. Ideally, you know, Eartha KITT, a few years before, had gone to the White House and protested the war to LBJ. We wanted something like that from Sammy Davis Jr. We did not want him there or certainly hugging Nixon, and I think we had the right to want that.

Interviewer: But. One of the other interviews is called, say, sort of a house Negro in terms of what he did.

Margo Jefferson: Oh, that phrase, the house Negro. I am a little tired of using it myself because it is so easily unanswerable, disdainful. And I have been in my past life as a critic very hard on Sammy Davis Jr. And I understand why there were it’s so easy to respond to his own neediness and the peculiarities of his self-doubts and self-hatred, which are always acted out in a florid, aggressive way like his talent is. But I’m I am I am more interested in in the subtleties as well as the egregious errors. He was more than there were moments when he behaved like what we call the house Negro, meaning the the the extreme, the almost the stereotype. Every house Negro was not, you know, an ingratiating bull, but the stereotype of the I will do anything to please my white masters. And if need be, I will disdain or betray any black person. That is, you know, the extreme negative portrait of a house Negro. He behaved that way at times. It looked in public. For example, the embrace of Nixon looked like absolutely the gesture of a nice house Negro. And momentarily, I think it was given the politics of the time. But that’s not the sum total of who he was. It’s an egregious moment, but it’s not the whole.

Interviewer: Because in his audiotapes, he talks about how, you know, after that moment and he became such a cause, such a brouhaha.

Margo Jefferson: Yeah.

Interviewer: And he said Ethel Kennedy stopped talking to him, Harry Belafonte.

Margo Jefferson: So quite quite a range.

Interviewer: Of acquaintances initially stopped talking to him. So many people who had been close to him just stopped talking to him. He was he was so painfully hurt and it was hard on him. Part of him grappled with understanding why because he said it was just that hug, which is a spontaneous thing that he would tell anybody.

Margo Jefferson: Well, you know, Sammy grappling with what it meant, he and the hug was a spontaneous thing. There is truth to that. You always in old footage, Sammy, hugging somebody or introducing someone. Now, Charro, you know, Count Basie, whoever it is, is my dear friend. And you’re thinking, No, no way. They can’t all be your dear, dear best friend. But that, alas, it it’s very poignant, but also kind of horrifying to me that he wouldn’t get it and that, in fact, it was so ingrained in him that I have to hug, I have to get love, I have to give love. And that he writes about in in his two autobiographies this need. You know, I’ll find a way to please you. And I try to track some of it back to those terrible, terrible racist experiences in the Army. And I think at one point I think it’s in yes, I can, he says. And, you know, when I became an entertainer, I realized that I could get I could get even the most bigoted ones. You know, that’s a source of power. But it also, for him became a source of or a gesture of, oh, I need you. Of just terrifying abject need. I’ll do anything to be loved by anybody in this moment.

Interviewer: Chilling when you just said that to you, to one of his signature songs became I Got to Be Me. Yeah. He sang it from the sixties to the end of his career. Who? Who was that? Me that Sammy was talking about, you know? And how many mes were there? Sammy Davis Jr.

Margo Jefferson: How many knees was Sammy offering to us and reminding himself up when he sang, I’ve got to Be Me. I wish I knew there. I think the various mes that he performed may all revolve around this. I am. And I am an entertainer. I am a star. And whatever I want or have to do to to blaze all as I feel it, as I receive it, I must do you know, I will make my presence felt by if I may appropriate a phrase from the militant sixties by any means necessary. And I have the right. I need it. And I will, you know, all the other ways of doing that. With so much technical prowess, you know, he could do so much, I think come out of come out of that that drive that that Uber me.

Interviewer: So you said you were very critical of saying what was something that you wrote about Sammy, where you really put him on the on.

Margo Jefferson: I it was Sammy the second volume of Sammy memoir, Why Me? And I reviewed it for I reviewed the second volume of Sammy Davis Jr is Memoirs Why Me for the Times? Must have been the Time, The Book Review. And I think that piece is in a Sammy Davis Jr reader. And I just I eviscerated him. I just I took every self-serving thing that he said. I certainly took, you know, the more humiliating moment. And I just basically said this is a portrait of a man who has sold now, sold his sold his soul. I wouldn’t not to the devil, but who has, you know, betrayed the best in himself. And this is a pitiable and in many ways contemptible spectacle. That’s what I said at the time. Wow.

Interviewer: I that you fellow.

Margo Jefferson: That I did that book is the is it was distressing and I was much of it was. And I was still very in thrall to you know the the sad the Sammy of, you know, the Candyman, the Nixon hug, the desperate, probably drug addled appearances on TV show after TV show Bojangles. You know, he wasn’t producing the kind of art, you know, he wasn’t using his craft in a way in those years that what would have allowed me to really say. But all right, let’s step back and see what he is still able to get. He hadn’t, for example, taken the, you know, the path of a Lena Horne, which really was to try to locate herself not always with such stylistic success in the late sixties, but to keep at it, you know, and to expand her complexity and and her craft in a very deliberate way.

Interviewer: Margaret, do you remember when when Sammy had his car accident, lost his life?

Margo Jefferson: I remember when Sam I remember reading about when Sammy had his car accident in lost his eye. And I must remember hearing various people, journalists, my family, friends talk about it. I certainly remember seeing him reappear with that patch. Right. You know, and there was that sense of, oh, my God, this, this, this, you know, I totally promise and gifted, you know, please, will he come back? And he did. And he did absolutely back.

Interviewer: So give me a sense of the Sammy Davis that you enjoyed filled with young girl of the 68 and the Sammy Davis you responded to after 1968.

Margo Jefferson: My my history with Sammy Davis Jr. In terms of what I enjoyed, I, I was excited and, and really often thrilled by the Sammy Davis Jr that I saw on television from starting in the fifties and moving through in terms of records. My parents had won some of his records. Let’s see. Did I? I even saw him in Porgy and Bess. And even though I knew I wasn’t supposed to like it because the black press was was hard on it in many ways, I was excited by him. So as a singer, an actor, an all around entertainer, I was excited by and, you know, and engaged with, not obsessed with, but engaged with him. Certainly through the mid-sixties. It started to change in the late sixties, partly simply because of music changes. You know, I, I turned 13 in 1960. So by you know, I was already that’s when I started getting interested in rock and roll. But I still loved musicals, you know. So I played Golden Boy, you know, constantly. But rock, soul, R&B really became more of a taste. And so he became less important. And then that meant he became a cultural subject and object to cultural figure who was role, whose performances as a as a black entertainer, who was a symbol. Yeah. And that’s those were really what became important. He was being judged as, let’s say, a race performer alongside James Baldwin, an increasingly serious Harry Belafonte. They were all clustering around Martin Luther King. So, you know, the the conditions of the theater, this was not just the theater on Broadway. This was the theater of racial progress, of civil rights, of racial strife. And so one became a little this one became a little more stern. As my politics changed by the late sixties, I pretty much considered him rather ridiculous.

Interviewer: You didn’t like this. And.

Margo Jefferson: You know, I. I didn’t I didn’t dislike it, but it just it felt that it felt always as if not that he was faking, but that he was over acting.

Interviewer: He would you do that once he did this and that.

Margo Jefferson: It just you know, Sammy was not most of the time. He was rarely a subtle performer, you know. So whatever he did, you know, whether he was clowning in it, you know, doing his fake doing his sort of broad Yiddish, broad black accents with the Rat Pack or doing black power, it was always going to be almost an exaggeration. And I but like I said, as a performer, subtlety was not, you know, what he was selling. I mean, there weren’t textures and inflections, but, you know, he was always going for the big delivery. And again, I think so was the social and political pressures contributed to that for sure.

Interviewer: Good governance. Again, I wanted to either talk a little bit about when you were saying you watched him on television and your family’s reaction to Will last and and Sammy Davis senior plays with say was a part of the Will Mastin Trio.

Margo Jefferson: Well, when Sammy was a part of the Will Mastin Trio and Sammy was a part of the amazing trio in those very early fifties years when he appeared on television, I was very interested in him. I was not interested in them. They were they looked old to me. They looked not very good, not bad, but just not necessary. And in those days we were so self-conscious, we blacks about in every little gesture, how it could be interpreted, what it could mean, what it showed about our hidden history as black people and what we wanted to be visible. And what was visible and exciting about Sammy was not only this aggressive talent, but the fact that it was climbing, clearly starting to claim center stage space. The Will Mastin and his dad, Sammy Davis Jr Sammy Davis Senior were not helping him as we saw and as I saw it claim center space. They were a throwback. And that’s not such a nice word that I’m describing how I saw them. They looked like a throwback. Back to his aspiring years, not to what he was already achieving.

Interviewer: Well, they were like a throwback to the second second stringer.

Margo Jefferson: To the second string vaudeville circuit that, you know, was not going to lead him into interracial, utterly, you know, white. Oh, we look up to you. Stardom.

Interviewer: Right? Good. Larry.

Margo Jefferson: Larry. And they weren’t making us proud the way he was. They weren’t Will Mastin and and Sammy Davis Senior. They weren’t shameful, but they weren’t making us proud with their bearing their man or the degree of their talent. And therefore, we felt let them recede.

Interviewer: As the world changed that much, though. This is not even.

Margo Jefferson: Okay as.

Interviewer: The world changed that much places black people in terms of this notion of identity and struggle.

Margo Jefferson: And who represents us best and who doesn’t? No, I think the the terms often change the same way expressions, you know, and the way you phrase your politics and the way you dress, those change. But the basic drives and struggles and needs emotional, political, psychological, sociological, those don’t particularly change. They get dressed up in new, new garb.

Interviewer: Baby in the mid sixties is not only acting with the performing with white guys, he’s performing a white man’s repertoire written by white men. So what does he have to reckon with? What is that tradition he’s taking on and have to reckon with that in the late sixties?

Margo Jefferson: Look, I think if I’m speaking as a kind of cultural critic, that’s definitely not helping. It’s working against him, but. And it’s working against him more intensely than, let us say, the Basie band, you know, a good jazz unit or Erroll Garner or Oscar Peterson or even Ella Fitzgerald singing the Great American Songbook. That’s not working against them in the same way, because they are wearing the mantle of jazz, which we are, you know, thinking of as a powerful black tradition that has always engaged wonderfully and fruitfully and excitingly with a lot of white material. I actually think and I you know, it’s not just Sammy’s problem. Again, Lena Horne is struggling with that. Nat King Cole, had he not died fairly early, would have been would have had to take this. And their audiences, their younger black audiences were going to shrink and younger black fans were going to run the gamut from, let’s say, sniffy, somewhat disdainful lack of in lack of interest to outright contempt. I think it would have worked less against him had he not been so visibly performing, not just with but for the Rat Pack.

Interviewer: Grant Black used a great word I hadn’t heard anyone use Dare. How? Sammy Davis Dare.

Margo Jefferson: First, Sammy Davis was daring, partly in the the kinetic aggression of his style as a performer. Yeah, I mean, I’m not saying I’m going to dance. I’m going to do imitations. You can’t possibly you know, you can’t can. You can’t contain it. I’m setting the rhythm, the beat, everything. For a young, short, considered very plain, which he was in those days, young black man to be claiming the stage in that way, he wasn’t being sleek and suave. Like Nat King Cole, you know. He wasn’t wearing, you know, clown costumes. You know, he was in his good suits. This was definitely daring. And he was also, you know, claiming mastery in me in all of these forms, you know, And then he moved he moved in to film. But the big thing was he couldn’t do it all. You know, Sammy the genius. And he he, he he took that. He took that mantle on himself.

Interviewer: And daring in the public arena to.

Margo Jefferson: Absolutely. Sammy was definitely daring in the public arena in that he he kind of merged the bravado. And again, this is all very manly, very masculine tradition. Male hood. He was playing with the bravado of the the playboy, the wealthy playboy around town, the hipster now with a torch, you know, of the kind of late night after hours, you know, daring, daring thing, the crossing racial lines. I have white male friends. I have white female lovers. Now, he was, you know, so in that way, with a touch of even a little bit of the bohemian there, and it was going to read as I am a black man, claiming my right to every source of entertainment and pleasure that I want. And I’m going to be a star and I’m going to you know, I’m not going to play just with, you know, black orchestras, you know, like so many great jazz singers did or an occasional, you know, white orchestra backing me. I’m in your Broadway theaters, I’m on your TV shows, I’m in your nightclubs. I’m the man of a thousand Faces in a thousand Places.

Interviewer: MM Did Sammy think in some deep way that he was talented enough to transcend race in Houston?

Margo Jefferson: Did Sammy think that he was talented enough to transcend the barriers, let us say, of race, which are social, cultural and emotional and psychological in terms of how your white audience perceives and receives you. I think he felt not only that he was talented enough, but that he had the strength of will. To act on this, to crave it, to want it at all times, and to go for it without shame.

Interviewer: Great. Good answers.

Margo Jefferson: You mean the Candyman? The Sammy of the Seventies, it seems to me was. Yeah. Let’s. Let’s go back to the Arthur Miller quote. He was losing his territory culturally. Again, he was. He wasn’t exciting to his old audiences anymore. And he wasn’t drawing in new audiences. Not really. You take a song like, Well, okay, you take a song like Candyman, which was a hit. I do accept that. So in that way he was commanding some new audiences. It was one of the worst songs, is a song that he sang in his entire career. You know, this was a man who had been singing to, you know, by and large, very good to really excellent, well-crafted, well-written songs. It felt when you heard him and I only heard it, I heard it on the radio. I must have seen him on TV again. It was overblown. You felt he was, you know, overdoing the you know, the chipper notes, the cutesy ness. You know, it he felt yeah, it it felt like a desperate move. And it did yield a hit. But for such a beautifully trained, crafty performer, it felt crude and desperate.

Interviewer: Yes.

Margo Jefferson: Because you don’t want talented people to take inferior material. And he did not do that. And this is just a really broad question. If that’s portraying the rest of himself, what is the best of Sammy? Oh, there’s the best of Sammy is in a lot of places. It’s in on some of his record albums, like The Way I Love Sam. That’s really good, Sammy. Some of the numbers on the Basie album, I think. I think like, forgive me, my mind’s coming back for a minute. I think. Golden Boy three I think Golden Boy is. I think he’s really good. Again, I didn’t see the show. I only heard the album. And there are all kinds of TV, TV performances, you know, where you can see this lovely is lovely use of all of these skills and energies. The very late Sammy. Sammy is very good in in intact bad movie. He calms down as as an actor. He’s he’s much older but his dancing is very good and he is holding his own with these old black hoppers. And I thought, well, bravo, everybody, including me, thought you didn’t have that anymore. That in some way you lost or even betrayed that tradition. And here you are and you’re you’re linking yourself to it. And you still have that skill, that talent. And then there you are with Gregory Hines, too. So the very late Sammy was some of the best in him. Yeah. And I love that he reclaimed it and showed all of us who really didn’t expect it.

Interviewer: So let’s the album show. Okay.

Margo Jefferson: Sammy Davis, Junior. Something for everyone. This is an unreleased Motown album. From what year? 1970.

Interviewer: It was actually, I would say, poorly distributed.

Margo Jefferson: Oh, I love it. All right. So this is an album Sammy made for and at the now. Well, if the by then legendary Motown, that was very poorly distributed. So we can say it was a flop. As this decade of challenges was beginning. It’s fascinating. First of all, the title. This is. This is first Sammy. Something for everyone. I will find a way to do this. The album cover perfectly in exact, with this kind of marketing moxie and cynicism, even that by the early seventies, you know, all producers and people, whatever understood about how you market the sixties, you know, you’ve got you’ve got cutesy little, you know, little mini mini dresses, you’ve got a little bit of boho, you’ve got allusions to African Egyptian, you’ve got straight blond hair. You’ve got to kind of what would be the Angela Davis afro was you’ve got the peace sign. You know, you’ve got people looking like they’re a little bit drugged out, something for everyone. And then in the sent and he’s in this kind of white robe, they could be North African, Egyptian or West African. And he’s in white, you know, meaning a kind of purity, as if he were a little bit of a god. And the songs, this is a hilarious set of versions of largely, largely not completely white artist hit hits. David Clayton-thomas. She’s a Sonny and Cher. Betty Sit down, kids. Start Misty one Stevie Wonder Elvis. He takes on Elvis in the ghetto. Okay, High heeled sneakers. Now, that’s a that’s a real old soul song at This is very, very interesting. But you know, of course I’m going to somehow or another show my stuff with all of these hits. I’m on the scene again. So I’m kind of bemused now and almost tickled by the fact that he thought, you know, this is also the old pro going back, you know, to vaudeville and early recordings. He thinks, look, I can take any song and make it work. I can do this. And that amuses me now that, oh my God, what a what a risk and how misbegotten, you know, it wasn’t going to be needed. My parents, who were still feeling, you know, some loyalty very much to Sammy Davis Jr, the entertainer, they weren’t going to buy this album. They didn’t give a damn about any of these songs. They wanted Sammy singing great old standards magic.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Margo Jefferson: Yeah. And I wasn’t going to buy it. I didn’t want to hear Sammy Davis Jr doing retreads of these songs, which by then are every one of these songs has has an or has still has a certain, you know, certain cachet. But it also every one of these songs also has a constituency that considers it ridiculous almost to caricature my ways. You know, better sit down, kids. You know it maybe in some ways Wichita Lineman may be the most creditable, but you don’t want to hear Sammy Davis Jr doing Wichita Lineman. You’ve got if you’re one audience, you’ve got Glen Campbell. If you’re another audience, you’ve got Isaac Hayes. So.

Interviewer: So say I’m going again. So you’ve been. You got. That’s great.

Margo Jefferson: Amazing, Larry. It was worth every penny.