Speaker So when I was beginning this career, America did not yet have a professional literary tradition to sort of frame that for us. So what was America like 30 years to return? Where did the POWs, the young, ambitious?

Speaker Yeah, well, the 18 20s and 30s in America, the literary scene was really just coming into being. There’s a great concern as to whether there would be an American literature at all. And people like Poe who were schooled in classical literature, he’d spent a great deal of time in London as a child. He wanted to make his mark and he wanted to be American. But in fact, that was one of the interesting things that he was pulling against, even as, say, people like Emerson and Thoreau, who we hear about all the time, and Hawthorne very much bent on being American poet, took a different tack. I think he was aiming for something absolute that would have universal attraction. And when the audiences worldwide that maybe not a particularly American literature would do so, even in the 20s and 30s, Poe was already kind of an iconoclast, kind of resisting the general forces of American literature as it was trying to become itself. When you look at his criticism, that’s one thing that he takes down those New England crazy eyes, as he called them, the transcendentalists. And, you know, why do we need something American? Let’s have something universal. And his principles of composition, his principles of his aesthetic also was quite absolute. Poetry had to strive for art stories, strove for truth. And I think you got a real sense of that in his tales. You don’t really know where they’re taking place the poems to. It’s not like Hawthorne. You know, you’re in Massachusetts and there’s a witch. You know, the witches, if they’re in Poe, they could be anywhere.

Speaker Say one next door? Yeah. Are they supposed to stop us?

Speaker We didn’t know what kind of.

Speaker Oh, doors closed over there could be the last that we did, I answer your question well, anyway, there was something in there.

Speaker OK, sorry. Yeah, yeah, yeah that was it. OK, great.

Speaker Let’s do another one more. I said. I’m a little more about this criticism. He had the nickname the Tomahawk.

Speaker Yes, vicious assaults. But what was he trying to do? Why was he so cautious?

Speaker Well, Poe and interestingly, Margaret Fuller, who were on the scene at about the same time, were very interested in setting up a standard for literary criticism. And I think for different reasons. Margaret Fuller understood that she was primarily a critic by nature. She wasn’t a novelist or a poet, although she tried those things. So she was defining criticism so that she could give herself a sense of professionalism. Poe was defining criticism so that he could establish his aesthetic. And as I said, the poems need to have a certain kind of rhythm. They needed to strive for beauty tales, for truth. He loved the tales of Nathaniel Hawthorne, for example. But as we’ve said, there’s hardly anyone that really stayed in his high esteem for very long. I think he was the only one who could really attain his standards. So he often used that position of critic to tear each other people down, sometimes because they were, in fact, terribly bad writers. But also they might have become personal enemies of his in some way or another. And he could go after someone he once adored. He could turn on them because they’d had a spat of some sort. But Margaret Fuller’s view was that the critic ought to enter into the spirit of the of the work and try to understand what the writer was doing and the context in which it was written. She, like Poe, despised the puffery that was going on or the mere impressions that that reviewers would give. Poe wanted to stake out a claim for absolutes, and it was all in a certain way self-serving. But both of them were trying to establish in the United States some kind of authority, just as the American writers, the fiction writers, the poets were trying to establish an American sensibility. Poe and Fuller, I think, because of their kind of classical training and their continental sense, were very much driven to establish a standard of criticism that probably wasn’t particularly national. It would have been international.

Speaker That’s great. Come on, let’s get to the last. But again, without mentioning Margaret.

Speaker Yeah. Yeah. To her. Yes. The chronology. So let’s think what I said.

Speaker What did you like about what I said they were trying to establish just as fiction writers were trying to establish, OK, they were trying to establish. OK, OK. You just described. Yeah. Yeah. OK, yeah. Yeah.

Speaker OK, so just as the American writers, most of the American writers, aside from power, attempting to establish a kind of American literature, a new age for writing in the new world, Poe was very bent on establishing a kind of criticism that would set out laws that were universal, that would gain international attention, who he was not in favor of an American literature, who was in favor of an absolute literature, absolute, you know, what should poetry do? What should fiction do? And he was going to prove this both in his criticism and in his own writing.

Speaker Thank you. All right, you want some water?

Speaker I wanted to say it’s we have new ones.

Speaker Oh, I didn’t put that there, but somebody put it there. Yeah. Yeah. Oh, well, I thought it did spill, but it was just a shadow of my Kleenex on the paper.

Speaker But they have been absolutely. All right.

Speaker You can it. So they were on the list.

Speaker So it’s how the young people sort of talking early 20s, very influenced by Byron, the romantic poets, can you talk about how he tried to sell fashion, kind of create an identity that were dressed in black and he carried himself a certain way?

Speaker Let me think about that when I have to say that was one that I not exactly stumped on. But but that’s something I want to, um.

Speaker That’s my. I thought, well, there was an interesting thing that Margaret Fuller said about him.

Speaker He was a little bit older, though he said it seemed shrouded in an assumed character. I like that when we get. But we can we can say that later.

Speaker And you other things. You know, when my questions later is what kinds of things? Oh, yes. Yeah, for the purposes of, um, I think there was just one more thing, I was his.

Speaker It of gets my thought about that gets a little bit into his romantic life, though, I don’t know. Um. OK, so, um, all right.

Speaker Because it’s easier for my brain anyway to move.

Speaker Yes, I understand. But, um. Yeah, um. Yes, I think we should just go, OK, when we go on. That’s OK to the publishing office at the time.

Speaker 1820 is 1837, a little before meeting for New York. But what was Poe up against in terms of wanting to be a writer and actually having to make a living as a writer?

Speaker Well, I think that the I’m not going to answer your question. The 18 20s and 30s were really a remarkable time for journals, for newspapers. And in some ways, it’s a time like ours. Today, there was a big shift from newspapers and journals that were controlled by religious sects. And suddenly there was, you know, just a search for an audience, a search to make a buck on these newspapers and or penny dreadfuls or literary journals. And there were so many of them, just the way we have so many outlets now, so many platforms. What was he to do? What was anyone to do? And Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville. And, you know, they did all kinds of writing early in their careers, often almost hackwork, we would say now, because they were just trying to get a foothold. And I think writers today can take a lot from their experience. Poe had the added complication of being a quirky guy and so he could endear himself to editors and and write up a storm. And then another kind of storm would break loose with his his temper or his drinking. And what had been a very powerful relationship might sour. And suddenly, you know, he didn’t have his platform anymore. In the case of the Broadway Journal in New York City, he became you know, he kind of became the editor and soul editor after differences with his partner and and then the publication itself died. So he was kind of his greatest friend and his greatest enemy in his prolific ness. But in his his personal quirks would often be more of a problem than, say, they were for someone like Nathaniel Hawthorne, his problems were other than that, he was very shy. He would not go out into the marketplace to sell himself. Poets, I think, kind of enjoyed doing that. And then he would get into verbal fisticuffs and do himself in.

Speaker Or sometimes real fisticuffs.

Speaker Yeah, um, how do you feel about the way he portrayed women in his stories and poems?

Speaker What was it? Yeah, well, I’m going to just look at that one quote that you know of, I’m sure.

Speaker And I’m not the first one to have said it.

Speaker OK, well, all right, the portrayal of women in Poe’s poetry and stories is a really vexed question, and we know we can’t help but think back to the deathbed scene of his mother when he was two years old and he and his brother gathered around and watched this beautiful young woman who was the only person they relied on, think and die before their very eyes. Now, what does he say in his philosophy of composition? But the greatest subject for a poem is a dying woman, actually a dead woman, a beautiful woman. And of course, his poems are full of things like that, full of imagery like that. Did that mean he thought all women should die? I don’t think so. But he was very attracted to young women, frail women, and found some kind of sense of beauty in that and wanted to capture it in his poetry. I think it’s important to remember that in that time, unlike ours, people were dying at early ages. Children were dying, parents were dying. And I don’t think it’s surprising that love and death should be merged in that way for someone like Poe or even many writers of the time.

Speaker And so I thought maybe that’s enough.

Speaker Yeah, yeah.

Speaker Premature burial comes up again and again in regard to that, let’s say I have to think about that.

Speaker Yeah, I know. I know, uh, the premature burial.

Speaker I’m not sure I can answer that.

Speaker So sorry. I guess something. Yeah. Yeah. Ask me again if you make a little note, we can come back to that maybe.

Speaker And so these 26 I think are 20 something. Maris’s 13 year old cousin.

Speaker What do you think about that?

Speaker OK, let me think how I could start that something. Answering your question. Many people who come to Thoreau’s biography are stunned by this fact.

Speaker Oh, sorry. Did I say Pottsboro? So maybe it just OK. Gosh, it rhymes. OK. Oh, all right. The last time I was doing this, I was talking about Thoreau out of the old man’s.

Speaker So maybe that happened. But that was six months ago.

Speaker Many people who are attracted to post life and his work are kind of stunned by the fact of his marriage to his very young 13 year old cousin, who was also not in the greatest health.

Speaker It seems startling.

Speaker It seems maybe like some kind of incest and abuse.

Speaker But at that time, it wasn’t quite I mean, always was more extreme than anyone else. But Emerson, Horace Mann, Longfellow, all married teenaged brides who were going to die in a few years of tuberculosis. Novelis, the great romantic German romantic poet, fell in love with a 10 year old who for whom he carried a flame until she was 13 and then married her. And then she also died of tuberculosis. So I think we have to see him in that context. Clearly, people were stunned at the time, but it wasn’t quite as odd as we think of it today. Now, he also, again, had missed his mother and the combination of cysts, as she was called, and and her mother. It was a household that he was marrying into and in a way, kind of protecting. There’s also a way, you know, I think about not just PO, but, as I said, Emerson Longfellow, Horace Mann, what was it with these guys?

Speaker And it was a time when I think men were under great pressure, literary men, men of intellectual ambition. How were they to find a way in the world? How could they support a family? And I get the sense that, you know, the attraction of the very young wife who, you know, might not bear children right off, might have been an attraction to them in some unconscious way. Was this really a marriage? We know that Poe didn’t have intercourse with his sissy the first three years and maybe never. Maybe that’s how he wanted it.

Speaker I never thought of. Yeah, take it, but it makes sense. Well, something might maitake.

Speaker You talked about this a little before, but just to do it.

Speaker Yeah, definitely. Yeah. The earlier one is his hack.

Speaker His work as a hack is amazing. What does that mean? What kind of work was the weather entail? How hard was it and how good was he?

Speaker Well, Paul was a really prolific writer when he wasn’t drinking too much. I suppose he was almost always drinking, but he could turn out the review those that wasn’t hackwork. But he could you know, the great balloon hoax, for example, is not hackwork, but it’s not really literature either. He knew what to what to do to draw the attention of the readers. And it was a skill that maybe served him. I don’t know. I’m not. What am I saying?

Speaker In a way, what I was looking forward to and maybe.

Speaker Yeah, yeah, I’m good with this, but know the fact that these magazines did not have a big stamp, I mean, it would have been.

Speaker Yeah, yes. He was in charge of all sorts of. That’s right. He had to fill up the bags. Yes, the things he had to make sure it was getting promoted. Yeah, yeah.

Speaker What a load of your bags. Yes. Um, OK.

Speaker Um, but the fact that he was so prolific to us, uh, somehow managed to do it quite well.

Speaker Yeah. Um, let’s see. OK, um.

Speaker OK, well, the proliferation of magazines and newspapers really required a whole army of writers and editors, except there weren’t really that many. And you’ll find that a lot of these publications were put out by one or two people filling out the back pages with who knows what, signing them anonymously or pseudonyms, that sort of thing.

Speaker I don’t I’m not sure I could count the number of different names or anonymous pieces that Poe contributed and probably will keep finding them for another century. You know, here’s another post piece that perhaps we can figure out. And it was just part of what one had to do. And I think, again, that’s that’s another way that our time is similar to that. You know, you get you get your words in print however you can. He always, though, had his eye on on the poetry and the tales and finding ways to get to his art. He knew where his his reputation would be made. And that was what I think it may have been. One of the sources for his frustration and his drink at times was that he couldn’t always find the place to get his poems published. He often in those days, you would have to sometimes do what today would think of as a vanity edition and get a friend to to subscribe, friends to subscribe or a patron to pay for the publication and then see if you could make that money back. I think that post best selling tales in 1845 sold 1500 copies that may have been the most he ever sold of any work. So that put him back on the journalism and editorial jobs as best he could manage.

Speaker There is this mother might be walking through the streets, yes.

Speaker Yes, I wanted to ask you. I’ve never been clear whether that was muddy or muddy, some kind of dramatic thing.

Speaker Also, did they call her Maria or Maria? What do you Maria? That’s what I thought that would probably be right. Oh, I’m sorry.

Speaker Just in case you. Do we have a problem with that? No, that was good. Oh, good. I think it’s rotators. Yeah, if you could just stand up just to sort just I just want rotate your chair that like.

Speaker There you go.

Speaker Is that chair OK? Oh I think you know. Yeah, I know. I’m just switching gears, Marilynne Robinson. Oh well she’s different. Different size. We could swap on my cell.

Speaker Oh no, no, I’m.

Speaker So we just do that as a separate what what was that what did he do? Why did you do it? Why did you write?

Speaker It’s really curious. And not long after Poe moved to New York City to work for the Evening Mirror and later for the Broadway Journal, he dreamed up this balloon hoax, which he sold not to either of those papers, but to the to the sun, the New York Sun. And his idea was to see if he could pull the wool over people’s eyes. He wrote up a very lengthy description of what purported to be a balloon flight from England across the Atlantic in three days.

Speaker And it was a notion that had kind of been in the air.

Speaker People thought maybe, you know, the balloons were going up well, how far could they go? And Poe drew on all the kind of speculations about this and wrote the most detailed account, you know, the the pounds of pressure of the gas and the amount of yards of fabric in this in the balloon, that kind of thing. And this came out and in an April 13th issue of The Sun in the morning and and evidently the paper just sold out so fast that Poe himself couldn’t get a copy of it. And so it was so widely believed that the paper had to finally issue a retraction two days later because they were worried that people were going to start trying to, you know, explore the facts of this. But, you know, it was something that was done. But that Poe did very well in Texas, you know.

Speaker Oh, oh. All right. I think there’s a thing here for me at the top.

Speaker Yes. The Tell-Tale Heart. So, yeah, we going to get later and let’s see if you want to pause right now. So I was like, can you turn it off? Or, um, that might not be that might be worse over there. Mm hmm.

Speaker Yeah, I think so. Yeah. Well, I mean, one of the things we’re doing now is good and it’s great that I think OK, time.

Speaker OK, so when he gets to New York for the second time, early 40s, Biddington for us, guess what’s the literary scene? That is what’s going on by the US.

Speaker Well, OK. Aside from the newspapers and journals that were just proliferating like crazy in New York City, 70 newspapers, five literary journals, there were these salons run by women, often poets, and one that he frequented was an lynchers salon. Saturday nights, 50 people might show up writers and editors at her house on Waverly Street, Waverly Square, in in the village. And the idea was just to entertain each each other with conversation. They call them conversation. A Poe really excelled here. His theatrical sense, which he’d inherited obviously from his parents, he could hold forth and he held forth primarily to the ladies. So while, you know, Horace Greeley might be there, the editors of these various publications and journalists, the the lady poets who appeared were often his great audience and that could lead him into trouble sometimes.

Speaker So to paint a little picture of what he would look like or act.

Speaker Yeah, let me just look for that. Uh, it’s see know I have how he described Fola and such things, but yeah, I know.

Speaker I’m just trying to think if I have how she described it.

Speaker Yeah. As we can get. Um, sorry.

Speaker I don’t have a lot of what he said.

Speaker Yeah, no, I just, um, I don’t know a lot about how you looked.

Speaker She was a bit there. Well, you’re comfortable to search it, yeah, dress, yes, in a way. And he was always a little I mean, I think you said yes. Shall we dress genteel? Yeah. Um, um.

Speaker Yeah.

Speaker Do you have a description, quotation that, you know, I’m just trying to think, um, I don’t even know how tall he was or anything, he wasn’t he wasn’t particularly tall. Yeah, yes. I know. Rob Villella can do that for you. Sure. Have you seen him do his part? Yes. Um. All right. So let’s see. Um, uh.

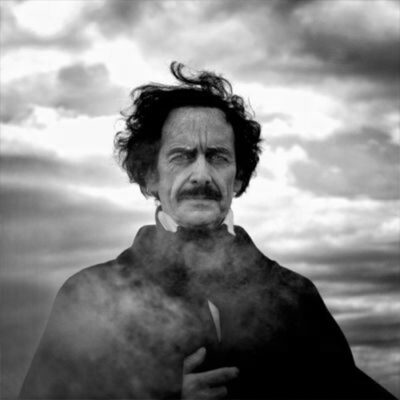

Speaker OK. OK, with a dark and kind of Thinley handsome man, and he always dressed in dark clothes, he liked to think of himself almost as the raven. But I think it was more than his physical presence that attracted people. It was the way he could speak, the way he could rattle off his poems with such great emotion and fervor, really capture an audience there. And I think that’s more as much what was the attraction.

Speaker His his really sorry. I’m trying to think, um.

Speaker OK, yeah, yeah. Po Po was a concentrated dose of medicine for anyone who met him and his intensity, it was said that he was a man who never smiled. I think that’s probably true. Even in these parties.

Speaker There was something about his melancholic look that attracted women as well as the fire that lit within him when he was reciting The Raven, as he would do what some of these salons it was, you know, the the bleak black figure with the pale face that drew in women really more than men, even though these could be a theatre for men to outdo each other and to dispute politics and and literature and art, Poe was more intent on capturing a female audience.

Speaker That’s great. I think they’re doing OK.

Speaker Oh, by the way, just as an aside, we’re also we’re going to interview in a couple of weeks when Colbert wrote a novel called Mrs. Oh, I’ve heard about that.

Speaker Well, I was going to ask, did you talk to Matthew Pearl or. Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker OK, he’s have a lot to say. Sure. But yeah.

Speaker This novel so yeah. I’ve heard of it. Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker So how was he about women. Other women that other writers. Women writers. I mean some people have told us that he know a critic of the time and we. It’s especially more seriously reviewed them with the same rigor, same high standards that panel is.

Speaker Yeah, yeah.

Speaker Um, Poe didn’t seem to distinguish between male and female poets, as you know, who might be capable of greatness. Women were often the ones he was championing, particularly Francis Osgoode, with whom he got into a bit of a romantic pickle. I guess we could say, um, I don’t think he saved women blows either.

Speaker But he was more inclined to take his hatchet to Longfellow or James Russell Lowell than he was to to the women. And maybe that was a bit of Southern chivalry, but it also allowed him to give them a kind of respect that was not really given them by a lot of other male critics. Even Margaret Fuller, a female critic, was not really one for championing women poets the way Edgar Allan Poe was.

Speaker And was there something about the subject matter that we wrote about versus what we’re writing about different?

Speaker I don’t know how to describe the subject. Hmm, well, I guess you are OK.

Speaker Poe valued rhyme and rhythm, a great deal in poetry, and I think the women poets that he put forward were really masters of that. It may not have been something that Emerson or Thoreau were really after in their own poetry, which I don’t think Poe particularly admired Longfellow with his long lines, his sort of, I don’t know, hypnotic in a bad way. Meter wasn’t attractive to Poe either. But the the lyric poetry of the women poets really drew him. And it was similar to something that he was after, although, of course, what he wrote lasted and what many of them wrote didn’t. We don’t remember Francis Osgood’s poetry or Elizabeth Elliott’s poetry the way we do poets. And it’s an interesting question as to why that’s the case. I think that Poe’s dark side was darker than any of them could provide.

Speaker So who were who were some of the luminaries? Well, you know, yeah, what about you? How do you think Pope felt been invited into this world? Because he was always such an outsider. He was always getting fire. Mm hmm. Always broke and always trying to beg people for another level. How do you think you felt when after Reagan was published and he was suddenly the darling?

Speaker Hmm. Well, Paul was a pope, was thrilled to have the audience at these salons, and he’d always striven for fame. And that meant a great deal for him to.

Speaker Oh, I’m sorry. I’ll start again. Um, yeah.

Speaker Um, maybe that would be good. You’re doing great. Oh, thank you. Um.

Speaker You’re painting a vivid picture just for that. Oh, OK.

Speaker Oh, it’s what we need. I mean, we have plenty of the.

Speaker Impressions and responses, yeah.

Speaker We’re talking more about the smell.

Speaker But this is great because you’re OK. Well, I’ll try. Oh, yeah.

Speaker Well, Poe was a seeker of fame from probably Boyhood. Maybe he learned something about this subliminally from knowing his mother was on the stage, even seeing her following around. How could he have that kind of success? And you can only imagine what it might’ve been like for him to suddenly be, you know, in demand as a speaker, as a reader, as a reciter in these salons in New York City. He he wanted fame and finally he got his fame.

Speaker But, of course, Poe had a very self-destructive side. And, you know, you want to kind of cry for him because as soon as he won this audience, he got himself into a mess with one of these women poets, Francis Osgoode, actually two of them, Francis Osgoode and Elizabeth Elliott, people who had been adoring him and these parties. And he began publishing Francis Osgood’s love poems to him and his to her. And it led to what was called the war in Bluestocking Dume. People felt that the letters that were exchanged between the two were compromising in some way. And this led to Margaret Fuller and Anne Lynch, the salon hostess, marching up to post house and demanding Francis Osgood’s letter back. He gave a nasty crack about Elizabeth Elliott’s letters, and that was kind of the end of any relations there. He was no longer welcome in an lynchers salon where he had once dominated, bested Margaret Fuller, been the shining light of in almost everyone’s eyes. He couldn’t go there anymore.

Speaker That was good because he answered two questions at once. So it’s kind of this kind of like, yeah, polish from beyond the grave, the music of the spheres.

Speaker Hmm. Yeah, but that was very.

Speaker Yes, it would be a good you know, that it’s a cop I know.

Speaker Well, I was really interested as I was studying up, I probably said this earlier in his review of Hawthorns Tales. He he said, you know, I’ve said that poetry has to strive for beauty, but details really are better than that. They they strive for truth. And I was surprised to find that we hear so much about his his aesthetic of poetry, less about the tales.

Speaker That’s come from that’s kind of major this I until Barbara. So it’s usually a major performance. Mm hmm. OK.

Speaker Oh, God, I forgot what we were talking about. Well, oh, I did the Warren Bluestocking them bluestocking.

Speaker Um, so you got to, uh, flirtation and.

Speaker Oh, I want to ask, is this was this the New York literati that he wrote?

Speaker Yes.

Speaker You described what I would say.

Speaker You know, I’m not going to probably be able to name two. I looked at that mostly. Just see what he said about Margaret Fuller in it, which was actually not all that negative, um, but, uh, just a sentence or two that he wrote this collection.

Speaker Yeah.

Speaker What was that for Goatees latest book? I think it was. Yeah. Um, uh.

Speaker Let’s see.

Speaker Well, Paul was suffering a series of social setbacks in 1845 after despite his great success with The Raven, he went to Boston and made a bunch of things and called those people names. And not long after that, he decided to go after the New York literati, as he called them, and in a series of profiles that he wrote for Godey’s Lady’s book. Now, of course, his ostensible reason for this was to establish what great literature ought to be. But he also ended up taking pot shots at many of the people he had locked horns with in the previous year.

Speaker One of them was Margaret Fuller, who had played a role in the war in Bluestocking.

Speaker He actually thought pretty highly of her as a writer, said she was a great stylist, but he also described her as she appeared in those salons as a woman with fire in her eyes, but a lip that was perpetually up curled in a sneer.

Speaker And she could also just sort of see this in the social scene. He said she could pay you earnest attention, look in your eyes, but then suddenly she’d be looking within or at the wall. He wanted full attention and she wasn’t giving it to him.

Speaker Tell us just briefly, Margaret Fuller, was what sort of place she had?

Speaker Mm hmm.

Speaker Margaret Fuller came from that den of Bedlam Heights and crazy nights in New England, in Boston that Poe really reviled. But he saw her as different from them and she was different from them.

Speaker She was the editor of their publication, The Dial. And in the first issue, she set out her theories of of what a critic ought to do. Just as Poe was setting out his theories, they had that in common.

Speaker And after a period of four years or so, working very hard in the literary scene in Boston, and she she gave that up to come to New York City to work as the front page columnist for Horace Greeley, New York Tribune. So they were applying the same trade at the same time. Margaret Fuller’s big hit was not a poem, not stories, but her work woman in the 19th century, which was really the first book of feminist theory published in the United States that came out in 1845. So her woman in the 19th century coincided with Poe’s Raven. What did Poe think of woman in the 19th century? Well, he disputed the doctrine, that doctrine. You can see why it would upset him. She said there’s no holy masculine man, no purely feminine woman. She felt all those traits could be passing amongst themselves in any given human being and that to, you know, achieve fullness of being, you would realize the feminine parts of yourself if you were a man, the masculine parts, if you were a woman. It’s a notion that’s very appealing to us now, but was not at all appealing to Poe, who glorified women, particularly beautiful dying women. But he did admire her style and he felt that, you know, no other woman could have written this book, no other woman would have published this book. But Margaret Fuller. And in a way, that was a compliment.

Speaker And what that wonderful thing about as a person, OK, that I will refer to my notes before I do that, because there are some peacocke.

Speaker And if these are here, you’d they’d be in the picture. Oh, I’m not making sound.

Speaker Yeah, OK, we won’t be able to shoot you.

Speaker Right, exactly.

Speaker So I just I’m going to end up there. Oh, yeah. Yeah. And then just. Yeah. Before you start talking.

Speaker Margaret Fuller was really an insightful judge of character. She felt that Poe, even though he could win these audiences in the salons, was shrouded in assumed characters.

Speaker Who knows who he really was? And when he tangled with these women writers or, you know, paid suit to them, she thought that these passions were kind of an illusion that he concocted to amuse himself. I think she was probably right about that, even as his heart often seemed to be broken by such things. But but they were passing fancies except for his lifelong attachment to sister Virginia, his wife.

Speaker OK, let’s see if I can answer about. His writing. There’s some good things.

Speaker OK, Margaret Fuller and Poe were both critics, and she admired his writings. She admired the standards that he upheld, but she felt he could be a little too severe. And I’m sure she was not alone in that. She wished that he could be affirmative more often, somehow put forward what was good about works. I think this was related to her notion that the critic ought to enter into the spirit of the work and not condemn it because it didn’t meet the standards of the reviewer. It should meet its own standards. She wished the Poe could do a little more of that. But Fuller herself was very damning of people she felt didn’t didn’t live up. And she and Poe shared a dislike of Longfellow’s work that got both of them into trouble. So that was actually something. That poem I admired about Fuller was that she was willing to go up against Longfellow and say, oh, he’s derivative, he’s too general. You know, what is he really contributing as far as Poe’s own writing, his creative work? She admired his poetry, although it’s interesting when he his poems came out in 1844, he had written this rather self-deprecating preface. This isn’t my best work. It will get better. And she said, I think we can take him at his word. We hope that he’ll get better. She liked the Raven a great deal. But she said his his verses could be like storm clouds gathering on the horizon, a sweep of images that could take over the reader. And that’s what she admired about them, even though she felt these, you know, weren’t his his best work possible. So she could be a little severe herself.

Speaker Yes.

Speaker I’m going to look at one more thing to say. Um, uh.

Speaker So like like Poe, Fuller also felt that the state of American letters of fiction writing off of tales was a little thin, and she was very happy to see Poe’s tales in 1845.

Speaker She felt that they were a refreshment in this climate of this dearth of great, great writing. And she admired what she thought was a kind of a genuineness, a real, a realism, curiously. And by that she meant a penetration into the causes of things. She was very taken by his psychological acuity in these tales.

Speaker There’s a quote all over the Internet. Oh, supposedly that, he said, but then I couldn’t find a, uh, authoritative sources where he said there are three kinds of people, men and women. Margaret?

Speaker Yeah, I’ve heard that. Well, you never know.

Speaker There is something, though, that, uh, it’s kind of like that, um.

Speaker Maybe I can, um.

Speaker I think I could say this, there was a sense in New York in the middle of 1848 with Margaret Fuller as the front page columnist for the Tribune and DPO running the Broadway Journal, that these were kind of two titans squaring off. Sometimes in the salons. They would actually have debates and you’d hear whether Poe had bested Fuller or Fuller bested Poe. But there was a way in which I think they both shared, aside from this absolute sense of the need for criticism, a kind of spirituality, surprisingly, for this New England transcendentalist that was fuller for the Southern. Who knows what his religion was for Poe. But he was said near his death to say that he hated the idea that there was any greater being in the universe than himself. Margaret Fuller was also tweaked for having what was said to be a mountainous me. She had famously told Carlyle that she would embrace the universe and he said, by God, she’d better. So I think that you see two great egos squaring off here, and it’s just fantastic that they landed in New York City at the same time in these salons. And and we have these tales still to tell.

Speaker That’s great. Do you mind if I ask you to do the things she said about how assuming that character would have that? Yeah. Yes, I know. Get it. Get it right. And, you know, I think it says so much about about film and about the way people perceive people. So she put my little card on that.

Speaker Oh, OK. Um. And see.

Speaker Let’s see, um.

Speaker When Margaret Fuller encountered Poe in these salons, she wasn’t as snowed by him as many of the other women, she felt he was shrouded in an assumed character. And I think today we would probably say she had been right. And these love affairs that maybe probably were never consummated, publicly waged in the pages of the of the newspapers and journalists with poems that he published. He thought that these were passionate.

Speaker Sorry, Margaret Fuller. If not, he thought, OK, just pick it up. Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker Um, OK.

Speaker Um, yeah. OK.

Speaker Um, Margaret Fuller thought that the. OK, Margaret Fuller thought that oppose public flirtations were a matter of a form of passionate illusion. She said that he amused himself by inducing and I think she probably was at least half right there. We know that he needed the attention of women, genuinely wanted their love. But many of these didn’t last long. And compared especially to his passionate love for sisters, Virginia Poe throughout his life.

Speaker I think you probably said this, but, you know, what is their relationship and. What does it say about his.

Speaker Hmm. OK. Um.

Speaker It’s interesting that Paul was able to get the OK, just the way the pope was very open to women poets.

Speaker I think he was open to Margaret Fuller as a as a serious critic and as a stylist. He, I think, valued her writing above Emersons, for example. He felt that if you looked at a fuller style, you saw the very best that you could find. He admired her travel writing, thought that her graphic images of her trip to the West in her first book, Summer on the Lakes, were were brilliant. And he wrote about that, too. So he was not threatened by women writers. He was drawn to them. I think the problem with Margaret Fuller was that she was much more than that. She was a dominating presence and a competitor for the attention of people in these salons. So he fought for that attention. And when she took a role in this war in Bluestocking, then he turned against her, maybe not her writing.

Speaker He still wrote, you know, favorably about her writing in the literati essays, but he did describe her as having a perpetual sneer.

Speaker Actually, you just to remember the other question, which is whether it was about competing with these women poets at the same time. I mean, I’m talking about a very different kind of way. I mean, what do you think? They all after the same.

Speaker Yeah. Yeah. The same writers as.

Speaker OK, so.

Speaker I think Paul was quite magnanimous in his view of these many women poets, his contemporaries, Nathaniel Hawthorne was famous for condemning the damned mob of scribbling women out there, all these novelists who are who are clogging the marketplace and making it hard for him to make a buck. You don’t hear that from Poe. And maybe that has something to do with the nature of poetry. Perhaps like as now the the market for poetry was, you know, only so so and to have his poetry set in the context of the admiring women’s poetry, maybe that made him feel good.

Speaker Thank you.

Speaker So his wife died in 1947.

Speaker I mean, what do you think they’re going to have to think about that?

Speaker Um, let’s see. Um, let’s see.

Speaker OK, well, we know that Poe took to his bed for several days, maybe longer, after SIST died. He was really dealt a blow that he should have seen coming, but seemed to be in denial about. And his writing? Well, he was already inclined, I think, to to terrible drinking binges. He had claimed a fit of insanity in the dust up with Elizabeth Elliott and and Frances Osgoode. I think those those periods of of insanity or of of absolute blotto drinking increased in the years after six died. He was really unmoored. He stayed in the household, though he he retained the connection with with Mudie, his mother in law. That angered him a bit.

Speaker But then this launched him on, you know, a series of near engagements, all of which turned out very badly.

Speaker The women he was pursuing were not 13 year old tubercular girls who were going to be reliant on him. These were often working poets who who had their own livelihood to protect. And they weren’t going to, in the end, link their fortunes to Edgar Allan Poe’s. So he had a series of love rejections. Again, who knows how serious he really was about about pursuing them. But I think it’s easy to see that, you know, it was only two years after Virginia’s death that Poe himself succumbed.

Speaker For a little more about the chasing of women after death. I mean, maybe, you know, because you rewrote the poem to hell.

Speaker I think he did that before as well. The poems to the Frances Osgood poems were also rewritten once.

Speaker I don’t know so much. I’m not sure I you. I know a lot about that.

Speaker But you would describe it generally. Yeah. Desperate. Um, almost.

Speaker So that was Sarah, Helen Whitman and somebody else. Annie Richmond. Annie Richmond. Um, her neighbor. Um.

Speaker Yeah, yeah, yeah, OK, yeah, well, so we’ve seen that post long marriage to or as long as it could last to Virginia, Clem was one for a much younger woman who was on the brink of death. His later pursuits seemed to be for women who might be able to take care of him. Very different kind of motivation. And I think they were on to that in him. So it was one reason that this didn’t work out. In the end, he was a famous writer and these were women of note, but not of the fame level of fame that Poe had. And perhaps for a while they thought they could improve their own fortunes, their own standards. And by linking their name with Poe, they also felt a great deal of empathy for this man. It’s interesting today, I don’t think many people would make this decision, but I think Sarah Helen Whitman felt she could cure him of his drinking. She hoped she could well, she lay down the law and he violated that law. So she terminated the relationship.

Speaker Just trying to think, yeah, yeah, um, yeah, I think you really care.

Speaker Mm hmm. And there’s one thing that I wanted to say also, I don’t know. Have you talked much about his drinking? It’s a little, but yeah, I think because Poe’s tales are dark and often surreal, there’s a sense that Poe’s imagination may have driven him to drink in some way, or that perhaps he he liked the kind of hallucinations that drink might give him. But if you look at his family history, you see that his father was a drunk, his brother was a drunk. This was a genetic problem that he was given that was not understood that way at the time. And I think it gives me a lot of empathy for him. It was a struggle, one that he, you know, had no way really of of breaking.

Speaker There wasn’t Alcoholics Anonymous. I guess there was the temperance movement, but it was that was more a matter of politics than of actually a cure. There wasn’t Antabuse, though. There weren’t choices for him to follow. And I think he probably was confused himself as to the source of of this thirst. But it was there and I think it’s what killed him.

Speaker We interviewed Help oh, oh, pardon? We interviewed Harold. Oh, yeah.

Speaker You know, destined to send. But he calls it a family curse. Oh, he doesn’t drink. He never drank. Yeah. So many relatives. Really interesting. Well, so you have that on tape. Probably you don’t need my statement. Mean we always like that. Mm hmm. Oh yeah.

Speaker OK, so you all know what you’re going to sell. I was looking at my, you know, the review I guess that you read of DPO of the Akroyd book.

Speaker And I thought, wow, I was really had an axe to grind there. My father was an alcoholic and somehow reading that book just stirred up my you know, I have no sympathy for poets drinking, you know, but I’ve been thinking differently about it, writing about Elizabeth Bishop, who was a terrible alcoholic. And, you know, similarly, the think it was a family genetic to.

Speaker Yes.

Speaker Yeah, I think I think he happened to drink as well. Um, why is. So ubiquitous and popular culture is on the cover of Sgt. Pepper.

Speaker These aren’t coffee mugs and aprons and. No books and God knows why. Why do we keep going this way? All right, let me think about that. Um. Let’s see if something I was going to say about that, um.

Speaker I think there’s a fascinating way that Poe has captured the popular imagination, he’s not probably the first writer that anyone teaching American literature would choose. They’d probably choose Hawthorne, Emerson, Harriet Beecher Stowe. You know, Poe’s writing is so in some way ephemeral or scary or threatening, but he created a persona that has just, I think, captured the minds of so many his images, his the way he presented himself in portraiture, his identification with the raven. You don’t want any you don’t want to say it was a shtick. But it’s one it’s a shtick that stuck and it’s just really everywhere. I think, you know, if Nathaniel Hawthorne were alive today, he wouldn’t be cursing the damned mob of scribbling women. He might be cursing Poe and the Raven.

Speaker I might say something else. I’m trying to think what else to say about that.

Speaker Your favorite story post story?

Speaker Yeah, no, I was asked to read that. But I have this poem which I’m trying to think if I can get the Conqueror worm, that’s.

Speaker And that’s the one that’s the one that’s in the body for the last election.

Speaker So it’s in the in the fall of the House of Usher. Actually, I don’t know.

Speaker It might be I I’m in a mansion. Oh, OK. Um.

Speaker All right, I might if I want to quote from it, I’ll have to pick that up. And I wish I had that kind of memory. I just don’t. Yeah, yeah. It’s probably better. Yeah, I just talk about the poem. If there’s a stanza. Yeah.

Speaker Or two or an image or something, show it. Yeah.

Speaker Well there’s a remarkable poem called The Conqueror Worm that Poe wrote not too long after what he always thought of as Virginia’s singing accident two years before her death, when she was just singing for him and had a hemorrhage so that there was blood rushing out of her out of her mouth. It was part of her consumption, her tuberculosis. He wanted to think it was just an accident. But the conqueror worm, the poem lets you know that he really is contending with the worm of death. This is a poem that also draws on the stage setting that he associated with his mother’s death. So it’s got it. And angel throng that’s gathered in a theatre and they’re watching the puppets act out the theatre, the the drama of life. And into this kind of ideal setting comes this dreadful worm. It rides, it rides, it says in the poem. And of course, the the end of the story is that the conqueror worm takes overall death, takes over all what I like about this poem, aside from this post style drama and melodrama almost, is that it brings together, I think, what he thinks considers the two great aims of literary art.

Speaker There’s the there’s rhyme, there’s rhythm. There’s the striving for beauty of sound in a poem. But this story or this poem also is a narrative. And he firmly believed that his tales or that tales could reach even beyond poetry to truth, beyond the beauty, that poetry sort tales could speak a truth. And I think that this really remarkable poem gives us both. It gives us beauty and truth.

Speaker Some of the well-known writers of ADAPT.

Speaker You know, a debt to power, and now I feel like I should be able to say many, but as I told you, I’m writing about Elizabeth Bishop and she’s the one who really comes to mind most. Is it all right to talk about her? Because you were going to talk to Pinski, who would probably talk about her.

Speaker But, um, uh, let’s see if you can start off by saying anything about America. Yeah. Yeah. Well, with that. Oh, well, that’s what I think. Yeah. Yeah, yeah.

Speaker Um, I see. Um.

Speaker OK, so Powys influenced writers since his death of all stripes and all nationalities, I think he was first picked up by the French surrealists. And in a way, that could be why Elizabeth Bishop chose him as a as a model. She was also taken by the French surrealists. And when she began writing fiction, she studied Poe’s theory of composition and his stories very, very closely and was herself trying to derive a similar theory of what a story ought to do, just as he’d said what a poem ought to do. It’s curious. She is best known for her poetry, but wrote really some remarkable stories during this time that she was reading Poe so seriously. One of them is called In Prison. It’s very Poe like. It’s somebody who is in prison, is happy to be there and, you know, just dreads the day when he or she probably she might be released.

Speaker And I think that both Poe and Elizabeth Bishop, you know, 100 years later, a century later, probably longed for a kind of confinement that would focus them on their work and on their art. They wished they could just have the room that would allow them to write both of them, interestingly, where it was serious drinkers. And I have to wonder whether that was another aspect of Poe’s life and work that that drew her. She didn’t much like Emily Dickinson, at least in those early days. She came to speak highly of Emily Dickinson. But it was Poe that she picked out as her American literary predecessor.

Speaker Don’t trust any other names.

Speaker I don’t know why I just have this blank about it, you know, because I when I was there, certainly a lot of contemporary writers who would say, uh, they were influenced, but I don’t feel comfortable picking out any one in particular, uh, disappearance and death.

Speaker What do you make of that? What do you make of the role it plays in all the.

Speaker Um, yeah, that’s a. Um, OK.

Speaker Well, I can’t think how many theories have come to the fore about those missing six days at the end of Poe’s life, and I suppose if I were a novelist rather than a biographer, I would spend some time working on that to, um, you know, we’ve talked a lot about the influence of his mother’s death on Poe, but what about his father? His father disappeared. Did he die? Who knows? Nobody knows what became of David Poe. I don’t really think we can say that Edgar Allan Poe disappeared trying to imitate his father. But I think there’s an echo of that in the story. And, you know, that’s it’s it’s a mystery piled upon mystery. And it seems, of course, very, you know, like a post story, this ending of Poe’s life.

Speaker But yeah, I was just thinking about that as I was reading this, why doesn’t anybody how could it really I mean, I looked in the Silverman I looked at, you know, does anybody say and why didn’t the family try to find him? I mean, well, what did they think? Or did they ever was it wrong? I guess.

Speaker But it was a fairly successful I mean, a fairly prosperous family. It wasn’t like she was.

Speaker Yeah, it’s his right side. I think I just always assumed they kind of just.

Speaker But do people really just do that? He’s gone, you know, and good riddance, especially if there are these kids. But maybe it was good riddance.

Speaker Supposed to be a boy matricide. Yeah, yeah, yeah. I’m happy about it.

Speaker I think that’s the mystery.

Speaker If it were me that I’d try to solve, actually, given that I just think given the context of our film, if you could just say one brief statement about how David would seems to have disappeared, I’ll never figure out what happened to that we could use right around that time. Yeah, his mother is about to die.

Speaker Yes. Let’s see. Um, um.

Speaker All right. So essentially just stating the fact of it. Yeah.

Speaker Setting the stage. Maybe you can say, um, when I was only two years old, his mother’s encouragement is also in Richmond. This is clearly dying that his father just disappeared.

Speaker Just just something we can use. Oh, OK. Um.

Speaker Sorry, what? Well, not only did his mother died, yeah, that, um, yeah, OK.

Speaker Um, um.

Speaker All right, so, OK, um, so.

Speaker Poe’s origin story goes back to age two when he was living with his ailing mother and his father had disappeared. Nobody knew if he died or just run off and assumed a new identity. So this boy was orphaned at age two. No father, no mother. Having witnessed his mother’s dying breaths, it was a burden too great to bear. Some have said.

Speaker Thank you. Yeah, OK. I read everything I wanted to.

Speaker You look at my things here, do you have anybody saying this I could not love accept where death was mingling his with butis breath and say, OK, fine, yeah.

Speaker You know, I love.

Speaker That’s. No, I don’t really know where it came from, I was reading, or at least in the Akroyd, it said he’d written it before age 20. Yeah. So I don’t know what that means.

Speaker Um. Uh, did you want.

Speaker Oh, we did say how he saw Margaret Fuller, um. Oh. Right. Um, and you didn’t want to talk about the Boston dustup necessarily.

Speaker I don’t know if that’s the right one. There are a few little quotes, but you probably have them, you know, like the the set of thumb sucking babies and idiots and that kind of stuff.

Speaker We’ve got that person.

Speaker OK. OK, are. Yeah. OK.

Speaker Short stories. Maybe because there is a point when Po Po wants to be a power money and that’s what he lives for. But by the time he’s working in Richmond with the Southern Literary Messenger, he’s realizing that. It’s just not. So, yeah, stories are so maybe if you can just talk a moment when he’s a young man, 20s, 20s by them, what’s happening in American literature in terms of poetry?

Speaker Yeah, prose. Well, everyone wanted to be a poet. Emerson wanted to be a poet. Poe wanted to be a poet. Thoreau wanted to be a poet. Margaret Fuller wanted to be a poet. Even Herman Melville wrote poetry. I wonder how much this had to do with the fact that the English and German transcendentalists, as we call them, romantics, as they’re known in literature and literary criticism, they made their mark in poetry. They wanted to be the American Wordsworth’s and Coleridge’s and Shelley’s. But maybe there was something in the American grain that hewed towards prose, towards tale’s towards you know, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s twice told tales they were very effective.

Speaker And Poe’s Tales of Russia’s nation, his mysteries, his dark, psychological, brooding tales.

Speaker These were perhaps easier to read even than poetry for the American public. And they found a bigger audience. His best book, not that it sold that well, was his tales rather than his poetry.

Speaker And maybe just one more sentence about how so early on he began to realize and see what the people. I don’t know.

Speaker Yeah. Yeah, I hope that’s true. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Speaker Um, I just realized that much as you want to write about. Yeah. If you want to make a living.

Speaker Yeah. So you think that that’s how that was. Right. So um um.

Speaker Um, so I had to Poe had married his cousin, he had his mother in law to support and poetry wasn’t going to do that for him. He took the jobs in publishing and he began writing prose, the criticism, the stories. And in some way he may have sensed that that was going to be where he would make his mark. He decided that, in fact, tales could tell a truth, that sometimes poetry could not. Maybe he was trying to convince himself of something he needed to he needed to do anyway.

Speaker Perfect. Thank you. And one more thing. Yeah.

Speaker I never really did ask you what so with these tales, the detective stories that I heard, the fall semester, I mean, they they’re different, but they have similar darkness. Can you talk at all about how he was tapping into a kind of new American anxiety? That was that was coming up in the section. Rapid urbanization, rapid industrialization, neighbors living next to each other who didn’t even know each other. God knows what they could be up to in the next world and that kind of thing. What was going on since that power was tapping into it, even though these stories were not usually said on Americans?

Speaker Mm hmm. Where were they said? Yeah, I know. Um, it’s interesting. Um.

Speaker Hmm. Um.

Speaker Um, OK, I think, um.

Speaker OK.

Speaker The America of the 1930s and 40s was really a great deal like the America that we’re in now. There were great financial panics in 1837 that most of the banks in the US went belly up. It was a time of great uncertainty for for Americans and the readers of newspapers and literary journals. And how was able to capitalize on this sense of worry, this nagging worry that you didn’t know really where it was coming from, these forces, the economic climate, what did that mean? And who could get a grip on it? The neighbors who were moving in next door. Suddenly there were tenements all over and and in New York City, when he was here working as a journalist, you know, there were suddenly institutions for the poor and hospitals for the poor had to be made because there were poor on the streets. There were immigrants. What was going to happen to this country? Nobody knew what’s going to happen to our country. Now, nobody knows. Maybe that’s why oppose having a revival today.

Speaker Thanks, OK.

Speaker I think we got everything all right, unless you want me to read from The Raven.

Speaker Oh, so you’re really in trouble with the radiator noise or the wonderful piece about the.

Speaker Oh, about the hoax.

Speaker Should I. Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker OK, um.

Speaker So, OK, well, soon after DPO moved to New York to work for the Evening Mirror and later for the Broadway Journal, he decided to pull a stunt not in either of those magazines because that might have been too transparent. He went to the editor of The New York Sun and proposed this article, which became a very long fake report of a balloon flight in three days. This balloon, it had crossed the Atlantic from England to America. And he went about it by describing in very great physical detail, you know, the the yards of cloth in the balloon and the amount of gas that was supposed to be released to keep it afloat.

Speaker It persuaded people so mightily that, you know, this this newspaper sold out instantly poster that he himself was unable ever to get a copy of it. And the newspaper had to issue a retraction in a few days time because otherwise people were really believing that this had happened. It was, I guess, kind of April 13th, Fool’s Day prank that he pulled. And when you think about the stories that he originated, the types of stories, there’s the detective story, there’s the psychological suspense story. Some people think that the balloon hoax was a beginning of a kind of a science fiction fantasy that Jules Verne later took up.