Interviewer: Thanks for consenting to do the interview. Tell us your name and where you’re from.

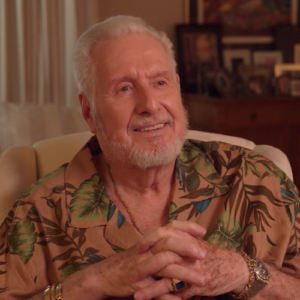

Mike Curb: Well, I’m Mike Curb. I grew up in Compton and Los Angeles, and I currently reside in Nashville, Tennessee.

Interviewer: When did you first become aware of Sammy Davis Jr.

Mike Curb: Well.

Interviewer: And include part of my question.

Mike Curb: Okay. Sure. Well. Having grown up in Compton, I was aware of Sammy Davis, even though most of his records in those days weren’t played on the little stations in Compton. I still heard them. For example, that Old Black Magic was the first record I ever heard by Sammy. But I would imagine that that record was probably around early fifties, but or mid-fifties. But I didn’t start recording Sammy until late sixties. But when I when I first started my record company 50 years ago when I was in college, I was interested in Sammy at that time and just I just loved his music, you know, I liked what he did, but I always thought it’d be fun if he would just do a little bit of R&B because we had Lou Rawls on our label and we had Solomon Burke and they were doing real solid R&B. We had the Silvers, and I just thought, you know, Sammy, if he would just do just let us put a little bit of R&B flavor behind the music. I thought we could get him played on the radio, and of course he would get a hit every once in a while, like I’ve Got To Be Me, which came from the musical world, Steve Lawrence and published it, and it came from the musical that Stephen Eady had done, but he would get a hit every once in a while, but it would be a very middle of the road type song and maybe it’d be once every seven years. And it wouldn’t it wouldn’t be a career defining hit.

Interviewer: So, Mike, why did you want to record Sammy? What was their motivation?

Mike Curb: Well, I had heard Sammy’s music throughout my life. I started school in Compton, California, and but most of his records were played on the maybe the mainstream stations that my parents listened to and the state of the radio stations that I listened to when I lived in Compton were probably the equivalent of like college stations are now. You know, they would come in from from from a restaurant or a diner or it’d be Johnny Otis’s concert. So you would hear. But the music in that I was listening to before Elvis, mostly in Compton, were mostly African-American artists like Joe Turner and Ivory. Ivory, Joe Hunter and and artists. And and in in the the great doo wop groups from that period, the Orioles and all that. It was even before. Well, maybe The Platters early hits were before before Elvis, but actually just barely. But most of those records that were hitting back in the late forties and early fifties when I was very, very young, when I was just starting kindergarten. Those records were before Elvis. And it was really funny because like Fats, Domino’s, I’m Walkin, which he did in 1949, I would hear on the little radio station. And then later on, when our family moved to the San Fernando Valley in California, I would hear the same song I’m Walkin, but it would be Ricky Nelson, you know? Or instead of Little Richard singing Tutti Frutti, it would be Pat Boone, you know, And big difference, you know.

Interviewer: And so Sammy, you folks, Sammy Sosa come out of the standard bag and play some more contemporary stuff.

Mike Curb: Oh, I thought he should do both. I thought that I always thought that of Sammy, because, I mean, let’s face it, when he was with the Will Mastin Trio, he was doing some pretty soulful things. And and in fact, Sammy had to restrain himself from doing soulful things for some reason. I think part of it was the relationship with Frank Sinatra. He would say to me, oftentimes if I presented a song to him, would Frank do that? You know? And then I would say to him, Well, you’re with Motown and you’re with Berry Gordy, who is the best? And the records didn’t hit. Is it possible that you didn’t record some of the songs Barry wanted you to record? And Sammy would say, It’s possible. You know, And in other words, he wouldn’t really the reason he didn’t have hits on Motown and the reason he after he had left for praise was he wouldn’t very he would sing those kind of songs that that that were Motown songs.

Interviewer: Why did he why did they go to Motown in the first place?

Mike Curb: Well, I think he thought he would get hits with Berry Gordy, you know, And I think I think it was a good thing, The Four Seasons. Who did The Jersey Boys? They went to Motown before they came to Curb, you know. But then when they came to Curb, we had all those big hits like, Oh, what a Night and Who Loves You? I mean, I had to persuade Sammy to even do the Candy man, you know? But having said that, he was a genius. You know, he just had he wanted to sing songs that he felt, you know, Frank would would like and that the audiences that he performed at Caesar’s Palace and in Vegas would like, you know, and I don’t I don’t blame him for that. I just wanted to get him on the radio.

Interviewer: Because he did a song for Motown called Something for Everyone. How did that how did that turn out when he went about that?

Mike Curb: Well, I don’t remember it. I don’t remember it. Which because it wasn’t.

Interviewer: Made in the song. I remember something that.

Mike Curb: I don’t remember something for everyone. The reason I don’t remember that song is because it didn’t get on the radio. And that’s the difference with Candyman. Candyman became a number one record. So if an artist I mean, whether it’s Debby Boone doing you a lot of my life or whether it’s Pat, whether it’s Sammy Davis doing Candyman or Lou Rawls, who did Natural Man on our label, if you don’t get that special song, it is done on the radio, then no one remembers it. And in Sammy’s case, once he did the Candyman, they called him the Candyman for the rest of his career. And I talked to him just before he died when he was in the hospital. And and and he still said, it’s amazing how people remembered him for that song because it was such a big hit.

Interviewer: So tell us about the genesis of how you got Sandy into the camp.

Mike Curb: Well, I knew Sy Marsh, who was Sammy’s manager, and we were friends. And when Sammy left Motown and I don’t know the circumstances of that, he was pretty anxious to do something that where he would get play. And Sy Marsh, his manager, really wanted to get him on the radio again, and he didn’t want to go back to Reprise. And Reprise had evolved with what had since been purchased, has been purchased by Warner and merged into Warner, and it was more of a rock. They were looking for Jimi Hendrix and rock artists. So basically the song came to me. I had I had just had a big hit with my own group, a group called the Mike Curb Congregation. We had we had performed the music from Kelly’s Heroes, the Clint Eastwood movie, and a song that I had written called Burning Bridges had become a fairly big hit. So the the producers of the show Candyman I’m sorry, the producers of Willy Wonka and the all star cut there, the producers of the movie Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory wanted my group.

Interviewer: To say the head of.

Mike Curb: The producers of the movie Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory wanted my group to record the Candy Man and have a hit like we had just had with Burning Bridges from the Clint Eastwood Kelly’s Heroes movie. So I recorded it with my group. And my mother doesn’t like me to say this, and she’s still alive. But it bombed with my group and we were just coming off a hit. And I put the record out and, you know, here’s my own group on my own record label and all that, and I still couldn’t break the darn record, you know. So it bothered me because it was a real infectious song, you know, And I had promised the producers and and I had promised Anthony Newley that we would really try to do something good. And so we signed Sammy. And I said, Sammy, you know, while we’re waiting to look for material, could I put your voice over the track of the Mike Curb congregation singing Candyman? And he said, Well, let me hear the song. And then he said, You got to be kidding me. You know, And, you know, he called it all kinds of names, but he said it in his book, too. You know, he called it white bread music or something like that, you know, And and he was right. You know, it was be And he said that it is he’s actually said this in his book. But, you know, I always took it in a positive way because he was always so nice to me, you know, and but he was real honest about his feelings and a real honest man, you know, And and so I was trying to think of what to say. And and then he said, would Frank ever do or something like this? And I said, Well, remember, High Hopes by Frank Sinatra, You know, just what makes that so silly? Old Ram think killed by a hole in the dam, you know, Remember then high hopes. It was a very up tempo, you know, high hopes to that rhythm. I said, this is the same rhythm. Frank did high hopes. And Sammy said, I always wondered why he did that song. I said, Well, I think maybe Frank wanted a hit at that time, you know. So anyway, he said, Well, look, I don’t really want drum. I don’t want I. I said, Well, just snap your fingers. You know, the candy man can they can just snap your fingers to it. And then he said I’ll make two takes. And so he made two. They said, I’ll make one take. And then, and then it wasn’t perfect. And so I took the blame and said, Hey, I didn’t do it right in the studio. Would you give me one more take? And he never did sing the chorus. So when you listen to the record and you hear the microbe congregation coming in, Candy Man can mix everything. I’ve got a horse voice. You know that part where the candy man makes everything he writes satisfying and delicious? That part. That’s what we had to bring the chorus and my group to do that, you know? And you could see why I had a group. It was like a terrible voice. But the so we had we spent all night dialing in the music to try to get get it right, and we just needed the drums. So finally I just got all the kids in the group to clap, and then I got our drummer and so we, we he sang it like this and then we added The Tin Man makes everything we make. So we put a motown drum in it. And it was really funny because I told that to Berry Gordy later on. He said, How did that how did you do that? And I said, We just learn from you. We put that Motown drum in right after, you know, after Sammy left. And then Sammy never told me what he thought of it. But when the record hit, number one, he was really, really happy. And it was a wonderful moment and gold record and number one record and I think kind of a career defining record. I mean, Sammy’s career is bigger than any one record, but they called him the Candy Man for the rest of his life.

Interviewer: So something like how come this song became so popular?

Mike Curb: Well, I wish I could look, I wish I could tell you that I knew Candy Man would go to number one ahead of time, but I would be lying. I was looking for a bridge record that we could get on the radio and that where I could keep my commitment to the producers of Willy Wonka and, you know, Anthony Newley and where we could get Sammy on the radio while we look for material. So I wish I had known it was going to be number one, but I didn’t. But I but once it started to hit, then since I own my own company, of course at that time I think we were merged. I had merged my company with MGM for a brief period, but the the Candyman started to break and we were able to get it on what they used to call top 40 radio stations. Now, today, you know, I’m still in the record business. And I think I think my company is the oldest company that’s still owned by the original owner. But today they call it contemporary hits radio or C, H, R, But in those days it was called Top 40 Radio. And and we they started playing some of the stations that were top 40 stations started playing the Candyman. And so I said to our promotion staff, let’s try to take this all the way, you know, because it’s one of those things. Here we are all these years later talking about it, and we wouldn’t have been talking about it if the record had gone to number seven. You know, and I still feel that way if we when we sign an artist, we have an artist named Lee Brice. Right now, we just battled one of his records up to number one, because when they go to number one, you remember them forever. And not that there’s anything wrong with a top ten record, but if that had happened on Candyman, we probably wouldn’t even be discussing Candyman right now.

Interviewer: Probably not. But the other thing is interesting, too. I mean, 1972, you know, next year to be reelected. Right. The country’s gone through this turmoil about Vietnam. Yeah. And stuff. Do you think that had anything to do with Candyman as popularity?

Mike Curb: Well, you know, there’s always turmoil. How about how about right now? You know, there’s turmoil in both political parties right now. You know, and there’s always turmoil during an election year. But I don’t know. I think people. When during a depression or a recession or maybe during a difficult political year. I think they oftentimes go to movies and listen to records that take them away from the negative things that are going on. You know, people get tired of turning on the news every night and hearing somebody negative about this group or negative about this group, or you get tired of that. And. And so if music and film are the escape, in fact, there have been studies that have shown that during tough election years or recession or depression years, people like, you know, music and they like film and they use that as a form of escape.

Interviewer: So Candyman becomes number one. Sammy is on a roll. Everybody identifies with that song. You right? 50 years later, people know two songs from, say, Mr. Bojangles and Candy Man. I mean, I remember, you know, I remember that old black magic myself. Yeah, that’s me who at 600 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, was listening to this song that sort of said, Sammy Davis is somebody we need to connect with.

Mike Curb: Well, President Nixon was running for reelection and he called me and he said that Candyman was his favorite song. And he said, Is there any chance that Sammy would perform as part of the Nixon reelection? And I said, I don’t think so, because I know he’s a Democrat. And I said, I just hosted a fundraiser at my home with Jesse Jackson and and Sammy for for the Rainbow Coalition that we were working on there and the Push for education project that Jesse was working on. And I said, I don’t know how that would blend. You know, I tried to say it politely. I don’t know how that would blend with what the Republicans are doing, you know? And and then he said he said, well, I’m trying to reach that audience. And I said, well, let me ask you this. Would you be willing to talk to his manager, Sy Marsh, because I’m the record company for Sammy. I mean, he’s recording for my record company, but I’m not the person that books Sammy into things. So I asked asked if we could have Sy Marsh call him, and then Sammy agreed to do the youth concert. Now, at that time in 72, just trying to think it was McGovern, I think that he was running again. So it was one of those situations where Nixon was carrying, I think he carried every single state. So and then I think one of the other members of the Rat Pack might have been Peter Lawford or someone else. I mean, I don’t want to use anybody’s name.

Interviewer: You’re talking about supporting.

Mike Curb: Well, Sinatra was it was was helping Nixon. I don’t know whether he fully endorsed him. But the same people who had supported Kennedy over Nixon, like Sinatra, were supporting Nixon because he won. He was already president and he was looked like he was going to carry every single state. So it wasn’t as controversial at that moment. Now, of course, later on after Watergate, obviously things changed. But at that moment, it wasn’t that controversial. In fact, my group, we always opened for Sammy and performed with him. I’m not always, but most of the time we did. If he was at Caesar’s Palace or in this case, we had the whole group there and I had Solomon Burke there. I had the silvers there. I had, I don’t think Lou Rawls. I don’t think Lou Rawls came. But whatever I had all my a lot of a lot of my artists ended up wanting to do it. It was actually a youth concert. It was in Miami, and it was it wasn’t part of the convention, but they videoed it into the convention. And and so it was just a youth rally and it was in the afternoon and and I was kind of filling in with my group, just doing a song. And then Sammy came in and we had just a we had just Solomon Burke had just finished and we had recorded I Have a Dream with with Solomon Burke. And we actually had Martin Luther King Junior’s words on the record. When I produced the record, the King family gave me the rights to to use the speech. So and when Solomon did I have a dream, and he did it in 72 and then he but then we were vamping and I kept saying, why are we vamping here? And because they kept saying to me, you know, keep some music going and then bring Sammy on, you know? And I said, Well, okay, but, you know, Sammy is going to come on when he wants to, you know. So we kept vamping and all of a sudden they pointed to me and said, Play candy, man. So we started the the the hook, the candy man. And Sammy walks out and starts performing. And then about one minute later, President Nixon walks on the stage unannounced. Sammy had no idea he was going to be there. I was standing right behind him. In fact, there was a big picture in Life magazine where I was standing right behind him. And Sammy was like shocked. And so he sees the president well, he hugs him. Well, the Secret Service, you there must have been ten Secret Service people wondering, what do we do? And you know, well, Sammy Davis Jr, you know, obviously he can do anything he wants, you know, But they’ve never they had never seen a recording artist run up and hug a president, you know.

Interviewer: And Nixon said anything about Sammy to sort of make that happen. It was just.

Mike Curb: Well, I think look, if President Obama walked in the room right now, all of us would stop what we’re doing and we’d run over to him and we’d want to get our picture taken. And you know what I’m saying? We would we would all you know, it’s it’s not a matter of who voted for the president or who didn’t vote for him. He’s the president. He as Sammy was a he’s the man, you know. So, you know, if when the president United States, who’s already president, walks on stage while you’re singing, it’s going to get your attention. And it got Sammy said he hugged him and that picture went on. You know, that’s another thing that still to this day lasts and.

Interviewer: Forever, because, you know, I was watching the show.

Mike Curb: Yeah.

Interviewer: And our conversations. Yeah. Sammy the interview and the interview as Sammy about that hug.

Mike Curb: Yeah.

Interviewer: And the controversy. Yeah. And Sammy said, if you had to do it all over again, he would have just said, Hello, Mr. President. He shook his hand.

Mike Curb: Right. But if you know Sammy, he had Sammy was a beautiful human being. So very he his emotions were great, you know, And he put that in his music. He loved to entertain. He entertained ever since he was a young boy in the Will Mastin Trio. And I mean, I think he was it was just an instinctive thing, but I think all of us would do the same if the president walked. If President Obama walked in. Now, I know I would run over and I wouldn’t I probably wouldn’t hug him, but I would. Yeah, I don’t think it would be appropriate for any of us to hug a president. But Sammy Davis, you know, I mean, Sammy Davis Jr is is is a lot bigger than I, you know, as a person. I mean, is Sammy Davis Jr had the right to hug anybody he wanted to you know and it.

Interviewer: Didn’t seem out of place to anybody at that time. Didn’t seem out of place to people when he hugged Nixon. I bet you.

Mike Curb: Well, no, it was it was it surprised? Oh, well, when he hugged him, it surprised me. But it also surprised me that President Nixon came on the stage because we had been told that the concert was going to be separate and that it was going to be videoed into the convention. But, you know, we had never been told that the president was going to walk onto the stage. So he came over from the convention and just walked on the stage.

Interviewer: And, you know, Sammy said yes to Nixon. I mean, these and he was a Democrat. Why did he say yes to doing the the youth rally The youth concert for for for President Nixon?

Mike Curb: Well, I think Sammy, at the end of the day, agreed to support Nixon because other members of the Rat Pack, Sinatra. And I think one other member I’m trying to think who it is, but one other member and some of the other people who had supported Kennedy over Nixon were supporting Nixon because he was obviously going to get reelected at that time. So I don’t think it was that unusual. Well, I thought it was good that Nixon was reaching out to the African-American vote. You know, I think that that, you know, by today’s terms, Nixon would be looked at as more of a centrist. I mean, he went to China. I mean, imagine if you know, if ever you know, I mean, you can think of many presidents, but if certain presidents had had if Jimmy Carter had gone to China or something like that, there might have been a a different reaction. You know, I like Jimmy Carter a lot. I mean, a fabulous person. But, you know, for a Republican president to go to China in those days, you know, was so Nixon would have been considered a centrist compared to, you know, what the Republican Party is today.

Interviewer: And it was it was so interesting that his his administration was reaching out to prominent black celebrities like Selma, me like James Brown. Yeah, like Jim Brown. Right. Is reaching out. I mean, why do you think he was trying to reach out to all these, well, prominent black celebrities?

Mike Curb: Well, I think he I think Richard Nixon was reaching out to prominent African-American celebrities because of the fact that he wanted to carry the black vote. I mean, I think in a political year, everything a president does is political. Every comment any candidate makes now has to be considered political. So, you know, during a political year, it was obvious that he was trying to reach out and carry that vote, which was good, that he was trying to reach out because he also was adjusting policies of his to try to reach out for that vote.

Interviewer: But, I mean, he was adjusting the notion of trying to create a sense of black capitalism that, you know, in terms of economically helping black people who have their own companies become much more independent.

Mike Curb: He was establishing enterprise zones and things like that. No, Nixon prior to Watergate, was headed in a really nice direction to be a centrist, at least compared to what we have experienced. Where one, you know, I mean, I hate polarization. I hate it when one candidate’s in this corner and one candidate’s in that corner and they hate each other. That’s not good for us. You know, and and so that particular year, because McGovern didn’t catch on as the Democratic nominee, Nixon was able to just reach out into all these areas. But I thought he was on a really nice track up until obviously Watergate. And then that ended the track all together, didn’t it? You know? Absolutely.

Interviewer: So I wasn’t saying, you know, this whole interview I saw, it was and it was like the party all the time. He was a fun guy. You know, he was charismatically was also self-destructive. You spent a lot of time to Sammy Davis and you must have seen all sides of Sammy Davis, Jr. Were some of those sides you saw Sammy Davis Jr. That you can talk about?

Mike Curb: Well, there were all kinds of different sides of Sammy. A lot of it depended on what time of day you saw him. You know, and but he was not what you would call a morning person. In fact, one day he he said one of the funniest things he said was he said, if you wake up in the morning and you’re not going to have a drink all day long, then the way you feel in the morning is as good as you’re going to feel all day long. You know, he he, you know, would wake up and he was not a morning person and he liked to record at night and sometimes late at night, you know? Yes. Well, Elvis Presley liked to record late at night. We owned the studio in Nashville. It’s a historic studio call, RCA, Studio B and I bought that several years ago because we use it for tourism. But Elvis Presley recorded 300 songs there, and we interviewed the musicians and they all said he really didn’t want to record until almost midnight. So people are you know, a lot of people are morning people. A lot of people are night people. Sammy was a night person.

Interviewer: A nice person.

Mike Curb: He was a nice person.

Interviewer: He liked the party, right? He liked to enjoy it.

Mike Curb: Well, of course he liked to party. I mean, it was funny in our recording and I had a recording studio on Melrose in L.A. at the time, and he would bring just before he recorded, in fact, when he was doing Candyman, three big guys walked in the room. I mean, they were like bodyguards, you know, and I mean really big. And they walked in the room carrying a bar and they set up a bar in the corner of the of the of the studio control room and then stocked it. And then. About an hour later, Sammy walked in, so he brought his own bar with him. So he he he wanted the ambiance. He was a live performer. He did not like to make a second take and a third take. He always said, if I can’t do it on the first take, the song’s not for me, you know? And so if you wanted a second take, you had to blame yourself. You had to say, Oh, I made a mistake in the control room because you couldn’t say, Sammy, you need to do this differently or that it was. And that might have been the problem with Motown, because Motown records are very structured. The tracks were designed I mean, you know, the Four Tops could sing the Over the Supremes track or a Temptations track or even Smokey Robinson. You could you could sometimes put different artists on different tracks, and they did oftentimes.

Interviewer: So Motown was much more structured, said Martin in Houston.

Mike Curb: Well, we had talked a little earlier about the fact that why Sammy didn’t have hits on Motown. And I think Motown in those days was very structured. Although Berry was trying to move away from that. I mean, when you look at what Diana Ross was doing and the movie themes she was doing and so forth, he he was certainly getting Diana out of the structured songs like she did with The Supremes. But I think, you know, like the Isley Brothers, when they did this whole heart of mine, they fit right in. You didn’t even know as the Isley Brothers. You didn’t know that was the same group that did Twist and Shout or whatever, because they fit right into that Motown groove. And it worked. I mean, it’s it’s one of the greatest things that’s ever happened to the music industry. But because you had a man like Berry Gordy who knew how to produce a record and how to have a rhythm section that could consistently turn out one hit after another with artist after artist after artist. The only thing about Sammy is he didn’t want to sing a structured song. And so that probably made it a little more difficult there. All right.

Interviewer: So let’s go back to the hug. So Sammy hugs Nixon. What was the initial reaction to that hug by the media of Sammy hugging Nixon.

Mike Curb: If you like? Well, obviously, when Sammy hugged the president, the media was all over it. There wasn’t much controversy going on in the election at that time because McGovern wasn’t doing well. And I think Nixon ended up carrying almost every state. So basically the media, I think, was looking for something exciting at the Republican conventions. And, you know, have you ever been to a convention? Well, I’ve been to Democratic conventions and I’ve been to Republican conventions. And they can be pretty to me. They can be pretty boring. But so anything that the media could find that was exciting. And I think just the fact that Sammy was hugging President Nixon, I think that alone was amazing. And then he had the number one record at the time. And President Nixon was saying it was it was his favorite record, you know, and the record was exploding. I mean, it was not just number one. It was just going to stay number one and it was going to just last forever and be played forever. So it was a great media event, actually, for both Sammy and President Nixon. Unfortunately, as events turned out a couple of years later with Watergate and so forth, it it kind of cast a different shadow on it. And it did. I still remember it as a positive event. I don’t know whether I don’t think Sammy remembered it well in his book. He even commented on me and commented on Sy Marsh’s manager. We they got us into that. And of course, we didn’t get him into it. President Nixon called us and said he wanted Sammy Davis. And anybody who knows me and anybody knows Sammy Davis knows that I don’t I never controlled where Sammy performed. I didn’t say, Sammy, you’re going to go to Caesar’s Palace. I was not his manager. I simply owned the record company and was the record producer on this particular. I wasn’t even the songwriter on this one, so. But having said that, I know that Sammy wasn’t happy later on that he did that. And, and and obviously Cy Marsh and I would not have asked him to do it if we had known what was going to happen. You know.

Interviewer: Because from from his book and from some audiotapes, obviously. And Sammy talks about how Belafonte started talking to him, Ethel Kennedy stopped talking to him. He became a pariah to people. I mean, do you remember how Sammy was reacting to the snowball effect of the negative reaction to the Bobby Nixon?

Mike Curb: Well, the fact that Frank Sinatra had supported Nick. Some at that time gave Sammy a lot of cover. And so, I mean, if people are going to criticize you, they’re going to criticize you for something. I remember I spent a brief part of my life in government. Years ago, I was asked to run for out of the blue. You know, I mean, I. I was asked to run for lieutenant governor back during the Ronald Reagan Jerry Brown years in California. And I had no political political experience except for my grandmother, who was Mexican, who had come over here, you know, in those days, I guess maybe by today’s terms it would be illegally. But and she she came over to Laredo, Texas, and put herself through college and learned, you know, learned about loving this country. Now, she was a liberal Democrat, but she would insist that I watch the Democrat convention and the Republican convention because she wanted me to love the country the same way she did, you know, And here she is, a mexican immigrant who put herself through college. That’s why I really hate to hear immigrants criticize because my grandmother, I have her her complete diary on on my website. She she she is an example of what immigrants do for this country.

Interviewer: But you but Sammy, I was reacting to this. This is all a negative.

Mike Curb: Well, all of us, Sammy reacted negatively to it after Watergate, but no one could blame him for that, because I think most of the country reacted negatively to it, no more so to the way it was handled then the event itself. It was handled just poorly and it well. It resulted in the resignation of a president United States. And I think that’s only happened a couple of times.

Interviewer: So you think it suddenly felt like he because of his hugging Nixon and because what happened to Nixon, he was sort of smeared. He was he was, you know, connected to Nixon because of him hugging him. And so anything that when Watergate happened, it just made Sally seem more of a pariah to a lot of people.

Mike Curb: Well, personally, I don’t think that the Nixon thing hurt Sammy at all, because I think Sammy is one of those people that’s bigger than the media, you know, And you see that in certain candidates, candidates that are celebrities, like Reagan was a celebrity before he was in before he ran. We have that same situation this year. When a candidate is a celebrity, they can get away with saying things that. Shocked most people, you know. And the thing is, I think Sammy was was doing so many great things for education and he was working with Jesse Jackson on on on education for our schools and trying to help schools like Compton, where I started school. So I just thought that I just think Sammy was bigger than all that. But we all know that if you’re a public figure. I know in the brief time that I was in government, particularly when when I was elected lieutenant governor and then the governor ran for president and I became acting governor of the largest state. Uh, you think I wasn’t criticized? I mean, every day. And now today, with with, you know, tweeting and everything else, you’re going to be criticized all the time. And so Sammy was used to being criticized. So I don’t think that bothered him. I just think that Sammy wished he hadn’t had not been involved. All right.

Interviewer: Yeah. Let’s switch to Mr. Bojangles. How did you first get across the song?

Mike Curb: Well, okay, Mr. Bojangles, It was recorded by a group called the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. And the Nitty Gritty. Your band still perform? I think to this day, I don’t know if they have all the original members, but they had made a very unique record of it. The problem is, in those days, particularly in the seventies, so many of the records in the seventies were one off artists. I mean, you could name a hundred hit records and the artist would have had one hit. You light up my life, Debby Boone, you know, that type of thing. One hit, and they even came up with the name. One hit wonders for the artists of the seventies because the Beatles had broken up at that time. So basically, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band were only known for that one song, and it wasn’t a number one record by them. And so I played the song for Sammy, but I played it again for the album. You know, again, it’s I can’t even I didn’t know Bojangles was going to be a big hit by Sammy, and I didn’t know Candyman. I mean, a lot of record producers like to lie about that, so I knew that would make a number one record that sound right. I mean, I knew it would be a good record by Sammy because he would make it his own. And I think what defines Sammy Davis career more than anything is whatever song he sang, whether it’d been a hit by another artist, his first hit, that All Black Magic had been a hit before Candyman had been recorded by Mike. Of course, no one heard my record, but the the fact that Sammy could take a song and make it his own, he did that with the Candyman, that the way he started the record, you know, you know, speaking and talking, you know. And the thing is, he did that later on with Shaft. He had a way of taking Mr. Bojangles and doing it in such a way. And in this case, we really followed his live version. In fact, we had so much trouble recording it because he essentially didn’t want he wanted to do it a cappella and his body, you’d hear his feet stomping. And in those days we didn’t have a way to get that out. So we had to have some instrumentation around it. But he just did the record like he would do live, and all I did was sit behind the booth and make sure that somewhat and you know, that we didn’t have a technical problem or whatever. I mean, it was Sammy just made that song his own and it was exciting. And he did that later on with Baretta theme, which which was a fairly big chart record. And we we did the theme for The Jeffersons moving moving on up to the East Side to a deluxe apartment in the sky. And he and and I thought he was starting to get into R&B a little bit when he did The Jeffersons theme. I mean, certainly gospel, R&B, you know, you know, And that was something he said. And certainly by the time he did Shaft, by the time he did the vocal verse and I mean, Isaac obviously had wrote it and had the hit was with the Bar-Kays instrumentally behind him. But when Sammy sang over that track, he made Shaft his own. And we even ended up using his version of Shaft when we sent the song to the Motion Picture Academy, because the people in the Motion Picture Academy, the young people do. Isaac Hayes and the R&B community who had bought the Hot Buttered Soul album, I mean, I knew. Isaac Hayes. But the Academy members didn’t know.

Interviewer: Isaac Hayes writes that. No.

Mike Curb: Isaac Yeah. I’d like to say that, but I can’t. I won’t put that on there. But I agree with you, you know.

Interviewer: So tell me, though, would you know, like Candy, man, what did Sammy think of Mister Bojangles when you first played it for me?

Mike Curb: You know, You know, he. Well, first of all, I probably had 20 songs because whenever I met with Sammy, I didn’t know if the next day he was going to go on a two month tour or I didn’t know if he was going to go up to Vegas for a month. So when I had a meeting with him, I came prepared with as many songs as he could listen to with Sammy. Once you got past ten songs, he said, he said, Hey, your job is to give me the best ten. Don’t. Don’t give me 50. You know, he wanted us to do our work. He wanted me to do my job, you know, which is to be the record producer. So I tried to screen songs that I knew he wouldn’t like. But, you know, he. I thought I could be honest. I couldn’t tell if he loved Bojangles or not, but he asked me if he could keep it, and then he performed it. My group was opening for him at Caesar’s Palace. And then he said, Are you are you going to hang around for my part of the show? I said, Well, of course. I mean, we we always came back at the end and did Candyman. And he said, I want you to hear the whole show. So I said, Sure. So I went out and sat with Altovise and we watched and we had a real nice booth and an alto and I were listening and all of a sudden he’s saying Mr. Bojangles. And and I went backstage and said, Doggone it, I wish I had recorded that live. Is that okay if I cut a recorded live? And he said, yes. So the next night we recorded the whole show live, which was good anyway, because it resulted in a live album. But then we went back in the studio and did a a studio. Well, we did a studio version of it, you know. And.

Interviewer: You know, when I first heard that song, I thought Bill Robinson, you know, I thought of Bill Bojangles Robinson. But I know when I listen to the lyrics. Yeah, about.

Mike Curb: No, I don’t think it was it.

Interviewer: Was it was the saying. They think that.

Mike Curb: I don’t know. You know, it’s funny. I don’t know who that song was about. I thought it was a fictional person, but Sammy Sammy did care about the the Delta musicians that had come over, you know, after slavery was abolished. And in the early 1900s, back when the Fisk Quartet was recording or or or 1932, when Leadbelly did S.C. write or something like that, he was intrigued by those kinds of things. In fact, I almost got him to record C.C. Rider by playing him, reminding him of the Leadbelly version that Leadbelly had recorded while he was in prison. And the the he was what I say, intrigued. I think his family maybe Will Mastin had had had had played music for him that went back maybe to the twenties and thirties and because he had an understanding of Delta music and I think he sort of saw Mr. Bojangles as maybe someone who had a one hit and was passed over and, you know, and then pulled himself up. I mean, I think Sammy identified that song maybe with someone. He just never told me who it was.

Interviewer: Another one of Sammy’s biggest songs or people that I remember, I think people because I got to be me, right? Who was it? Who were the different meanings of Sammy Davis Junior, from your perspective?

Mike Curb: Well, the that particular song, you know, it came from a Broadway show and Steve Lawrence, the singer of Stephen Eddy, published it and did it in the show. And Steve brought that record to Sammy. And Sammy was still on Reprise at that time. This was maybe seven years before Candy Man. So. I got to be me. To me. I think Sammy was doing my way. I doubt I felt like he. And it is funny because I actually discussed this with Steve Lawrence, who is still, you know, EDI died, but Steve just recently did an album and we released it on our record label. And Steve, I think it’s about 78 or 79 now, but sings great. And we were talking about that and he and I said, Steve, what caused you to take that to Sammy? He said, I felt that could be my way for Sammy. And, and, you know, Sammy never said that to me, but the way he performed it, I think he tried to make it his career, recorded it. I don’t know if it turned out to be a career record. He sang it in every show he did, and he would sing it near the end. It wasn’t as big a record on the charts as Candy Man, but I think it’s one of those records that I know When we did the live album, I made darn sure we had I Got To Be Me and What kind of Fool Am I, which was also a very, very significant song for Sammy, even though it wasn’t considered a pop rock record, it was certainly a very significant career song. I think for Sammy.

Interviewer: You talk about city lights and golf balls and these are certainly the same thing. Would you make?

Mike Curb: Well, Sammy cared about all people. He had no prejudice. He obviously. Well, he became Jewish. I actually went to the temple when when he became Jewish, I actually attended that ceremony. But he cared about all people, whether they were Jewish, whether he cared about gay rights. And we had several gay rights events. He had one at his home. And, you know, back in the seventies, that was not as easy to do. Even now, with some of the freaks in in that are in elective office, that, you know, it’s hard to you know, you still have people that are against gay rights, which is ridiculous. But Sammy was would do a gay rights event. He would do an event for the Jewish community. He would do a event for education for young African-Americans at Compton back in the area where I started school. I mean, he was a good, good human being. He had no prejudices of any kind and any he loved music. And if I got to be me was was Sammy being himself, then that’s a good thing. And I’m not saying that he didn’t have moments, but tell me an entertainer who hasn’t had moments that they would change, are there moments that all of us have had that we would go back and say and handle differently? You know, but I think Sammy, I’d classify him as well with all with what has been maybe one of the greatest people of all time, just as a human being, not to mention being maybe one of the greatest singers of all time.

Interviewer: You didn’t tell us how you first met Sammy. How did you first meet him?

Mike Curb: Well, and we’re trying to think his manager. I’m just trying to think where that occurred. The Marriott. He was obviously with me because his manager, Sy Marsh, had invited me to the event. Sy was a friend of mine and the event where he was becoming Jewish. It was a two hour event and a temple and I had been invited to that and I’m trying to think if that was the first time I met him or if I had met him, because no, that occurred. Yeah, that that would have occurred. Am I wrong? Like 68 or 60? It’s so hard for me because I’ve been doing this for so many years.

Interviewer: You become Jewish early and then you convert, yet you converted technically around.

Mike Curb: 59 another time. So I went to a ceremony around 67. All right. I went to a ceremony at a temple while he was married to me. Brit. And it was it may not have been I don’t know whether it was formalizing being Jewish or whatever. I just know it lasted forever. It lasted for like 3 hours. And I was invited by Sy to go. And it might have been yeah, I was invited by Sy to go to it. So it might have been closer to mid-Sixties or whatever, because somehow it’s the first time I remember shaking hands with him and, you know, congratulating him and all that. So it was some kind of a ceremony. Maybe it was a recital of his commandments. Maybe someone in here knows what you know, whether you have to maintain that or not. But, uh, but the bottom line is, he was still married to me, Brit, at the time. And so it would have been probably in the mid sixties. And then I didn’t see him probably for two or three years, I don’t think. And then I think I met him at one of the shows in Vegas and shook his hand. But it was really, again, Sy Marsh who said to me, Mike, he’s off Motown. Would you try to get a hit for Sammy? And that’s when I really got to know him.

Interviewer: Right. Okay.

Mike Curb: Yeah, But it was really and in all honesty, I really went to I think it was more because of Sy that I went to that event back then. It was just he just said, this is this will be it. I’d like you to meet Sammy. So, Sy, I don’t know. I don’t even know if Sy was the head manager or just his agent at the time. But Sy was a real close friend of mine and he he was wanting to connect me with Sammy back in the when I was just starting my company. And in the sixties, you know, So.

Interviewer: When Sammy started calling for you, when you first started your record association with Sammy, was your first reaction to Sammy the performer? Sammy No. What was your first reaction?

Mike Curb: When I first when you.

Interviewer: First start, when you sign saying to your your label, you know, what are your first reactions when they came to your studio And you know, you you know, you start to hit songs was your first reactions.

Mike Curb: Well, I’ll be honest with you, because Berry Gordy asked me the same question. He kept saying, How come the Osmond Brothers? How did you how come you had them cover the Jackson five, you know, when they were doing one bad apple? And you know, the sound a lot like ABC but the Jackson five, he said, Why? Why did you sign the Four Seasons? He had had the Four Seasons. And, you know, then we had big hits with them and then they became the Jersey Boys. Well, he said the same thing about Sammy. He said, How did you know that that that was going to be a hit? And I said, Barry, I did. I said, In fact, you, Berry Gordy, had more to do with this than me, because basically I used your drum concept. I had to wait till Sammy left the studio, but I put a motown drum over the record. So when Sammy was doing it, it was the Candy Man. Ken But when we put the drum on, it was the candy Man can be candy. You know, we put a loud double drum with him, handclaps. So we were. So I told Barry, I said, Barry, you could take some of the credit for this because you it was Barry who showed us how loud you could do the snare drum if you didn’t put the cymbal in air. Everybody always thought a drummer had to have a symbol and this and that. Barry showed us that you just needed a pounding backbeat on the record, and you could make the drum as loud as you wanted it, as long as you didn’t have a symbol cluttering up the record and take it and take it away from the guitars and the other instruments. So I told Barry that he probably had he could take some share of the credit for it, and I certainly didn’t know Candyman and Bojangles were going to be as big as they were, you know, I mean, it would be I couldn’t look you in the eye and say that, you know.

Interviewer: So what was then his reaction when they heard the produced version? Well.

Mike Curb: Well, Sammy liked the records once they were produced, you know, and I stayed all night. And I in those days, we had three track recordings, so we had to get it right. And I mean, Sammy wasn’t going to come back and give us another take on Candyman. So if somebody had arrested or, you know, and then I had to dial my group in to do the parts that he didn’t want to sing on the record, but I had no idea that it was going to turn out. But I knew it was a great record when it was done. I just didn’t know whether Top 40 Radio would play that alongside the records of 1972, you.

Interviewer: Know, So. So let me ask you this question. Like Sammy Davis, you came to your recording studio the first time you came and sat down with you. What did he say he wanted you to do for him and an artist, or did he say anything?

Mike Curb: He said he wanted a hit record. Sammy Davis said to me, I’d like to have a hit record. And he and, you know, Lou Rawls had already had Natural Man. He said, Where did you find that song? He said, I would have done Natural Man. And I said, Well, quite honestly, a publisher brought it to me. But, you know, again, nobody told Lou Rawls what to do, you know, In fact, Lou Rawls even changed our musicians. And because he wanted it to be more jazzy in the beat, we kept the drum, the Motown drum on that, too. But but I’m just saying that, in fact, Natural Man won the Grammy instead of Candyman that year. So, you know, I guess I couldn’t lose that year. But but, you know, in all candor, I had wanted Sammy to get the Grammy, you know, But then, you know, obviously, I. I love Lou Rawls. I still do.

Interviewer: He was saying that he wanted to hit.

Mike Curb: Anyone to hit and he won. But he would say things like that from some of the records we were hitting with that he like he liked Solomon Burke. He liked what we were doing with Solomon Burke, but he didn’t want to do R&B. Well, everything Solomon did was R&B. In fact, we had even toned the records down a little bit to get him on the radio. I mean, Solomon was a walking R&B giant. I mean, I, I, I’ve never in my life ever experienced anything like recording him. He so much gifted talent, you know? And the same with Sammy, same with Lou. I mean, I was just very lucky that that I was able to sign these artists and get hit records for them, you know, And but at the end of the day, it’s the artist, you know, it’s just a matter of. But what I learned from Berry Gordy and what I learned from Albert at Stax and all that is you got to get the rhythm section right. If you get the rhythm section right. And Lou Rawls wants the piano to be jazzier than fine. If you get the rhythm right and Sammy wants to only sing part of the record or wants to change the introduction or whatever, so be it. But you got to get the rhythm section right. Motown taught us that. Stax Records taught us that. How many times do we have to learn it?

Interviewer: So my final question, Larry. I have a couple. Yes. So if a 15 year old, 14 year old wants to know something about Sammy Davis Junior today in 2016, what would you say they should know about Sammy Davis, Jr?

Mike Curb: I would tell a young person, particularly if they wanted to be in the music industry. And I tell that because our Our Curb foundation has ten colleges across the country. We have one at Cal State in Northridge with 5000 students. We have one in Nashville with 2000 students. I tell the students at our colleges always find the greatest talent you can find when you record. Always find the greatest song you can find. No matter. Don’t think you have to write it yourself. I mean, there are people who’ve been able to do that, but everybody’s not Bob Dylan. You know, but and you know, if you get the best songs, forget who wrote them. Forget who published them. Get the best artists. And if you have the best artists and you get the best songs and then it makes you look good as a producer. I mean, you have to do it right? But then don’t be afraid to get the best rhythm section you can, get the best of everything and put all the odds in your favor. That’s what I tell our students. Get put all the odds in your favor. And then I guess luck is when opportunity and preparation meet. I don’t know. But you need a little bit of luck, too.

Interviewer: Though. What would you tell us, Sammy Davis?

Mike Curb: I would say he’s the greatest. I would say if you ever get a chance to to if you ever get a chance to work with someone like Sammy Davis, whether you’re doing his album cover, whether you’re producing him, whether you’re writing for him, if you ever find that person. Then get close to that person. And in whatever your field of expertise is, you will look better If you’re working with great people, people who lift you up. It’s the same thing we tell our kids. We just hope that they will be around people who lift them up and don’t pull them down. You know? That’s all you can hope for, isn’t it? So with Sammy Davis, Sammy Davis lifted up everyone that he worked with. Every member of the band was lifted up. You could ask Rhodes, who was his conductor for years. He’ll tell you. Is he still alive? How do you go? Oh, no. He was such a wonderful guy. He didn’t do Candyman. He was on the road. Don Costa, who did, by way, for Sinatra when Don Castro had produced all the Paul Anka records. And when Paul wrote My Way, he had died. Don did my way with Sinatra. But I had Don Costa come in and do Candyman when it was just my group.

Interviewer: So Sammy would help lift everybody’s musical chops.

Mike Curb: Sammy Davis lifted everyone in the room, whether they were a musician, arranger, producer. He just lifted everybody spirits and he was so gifted and he lived to perform. When I lived in Compton and I was starting elementary school, I used to hear small stations that would be broadcast from little restaurants and from small venues like Johnny Otis. I would be in town or something like that, but my parents would listen to the main radio stations and you didn’t get to hear very many African-American artists on those stations. You would hear Louis Armstrong, you would hear Louis Armstrong, for example. I remember in 19, I remember hearing Lucky Old Son, probably around 1950, performed by Louis Armstrong. He was accepted on on on white mainstream stations. Sammy was accepted when he did. Hey there. And when he did that, all black magic, he was accepted on the so-called I don’t like to call them white stations, but mainstream stations. But they weren’t playing any of the African-American performers who were doing doo wop records. They certainly weren’t playing Fats Domino and people like that. In fact, they were even playing the cover records.

Interviewer: They weren’t playing the original game.

Mike Curb: Yes, I remember Chuck Berry was the first time I ever met Chuck Berry. I said, How did you learn to play the electric guitar like that? He said, I learned to do it because I knew that the white guys couldn’t cover me. He said they couldn’t cover me because they couldn’t play the electric guitar the way I did. So he used the electric guitar so that he could have his records played on the mainstream stations. And of course, later on, when records like Blueberry Hill came along and you know, you had Bartholomew producing Fats when he was on Imperial, then he was on the mainstream stations, but that didn’t occur to like 50 late 55, 56. And that was after Elvis was starting what he had started in. He had already had Heartbreak Hotel and all that. So basically Sammy never cared about being played on what was called the rock and roll stations, but he was played on the mainstream stations that were playing Rosemary Clooney and Sinatra, you know, and that’s when he was on Decca, and that was throughout the fifties. I was very young at the time, so I heard his records on the radio stations that my parents I mean, we just we didn’t even have a TV. We just had a little radio. But I would hear I remember, Hey there. And of course, Rosemary did also, you know, and and I remember the one I remember most definitively was that old black magic. And then it came back again in the late fifties with Louis Prima and Keely Smith. And, you know, and so I don’t I was I was really just a young boy living in Compton and then later in the San Fernando Valley during the Decca years, but certainly aware of very always loved music and very aware of Sammy Davis. Jr.

Interviewer: Black You talked early on. He was so great about how a.

Mike Curb: Performer needs a signature.

Interviewer: Song to kind of embed.

Mike Curb: Their persona.

Interviewer: In the consciousness. And you seem to imply and you talk about that until Candy came along, even though the guy was recording two or 3 hours a year for a decade, he never had a song that was his.

Mike Curb: And maybe talk.

Interviewer: To say, if that’s true, and then what kind of what kind of what kind of impact?

Mike Curb: All right. By the way, I was going to ask you, you said. Sy Marsh. Sy. So life. I was I was going to call him real quickly and ask him when the event at the temple was. But but I’m thinking mid-sixties because I just started my company. And so I was one of those people who like me. It was kind of a mentor in a way. And he said, You’re going to you want to see something really nice. And he took me to his temple where I assumed Sami was converting at that. But I didn’t know what he was doing and I didn’t understand all the language was very, very intriguing to me to hear it, because I had never been to a temple before. You know, but and so I was going to say Sai might be able to tell us what year that was, but he’s he’s dead to. Is in Georgia and Georgia is dead and. Oh, God. How’s Alto?

Interviewer: She’s good.

Mike Curb: Alto is not dead, is what you’re going to hear now. You’re going to make me too sad to do any more interviews. You’re out.

Interviewer: You’re up for this one. Wow.

Mike Curb: Alto. What? When did alto die?

Interviewer: Once, nine years ago. I’ll tell.

Mike Curb: You what. When I moved to Tennessee, I lost so much of myself. You know, I like Tennessee from a music standpoint because it’s the music center of the world right now. But, you know, you lose you lose contact with Steve Lawrence and you lose contact with Alto.

Interviewer: And we’re going to.

Mike Curb: World War II. Oh, okay.

Interviewer: About a signature song from it. How important it is for you.

Mike Curb: Okay.

Interviewer: We may not have had one until.

Mike Curb: And you. Well, one thing we know about a signature song is a signature song is not always the best song. It’s not always the best produced song, but it’s the song that the public connects with. Sammy had wonderful records that all black magic would. Hey there. What kind of fool am I? I’ve got to be me. He had wonderful records, but the Candyman, because it was picked up by top 40 radio and it went to number one, and it lasted and lasted. And Sammy enjoyed doing it. And every time he did it, people stood up. It became his signature song. And the one thing we always dream of and we’re celebrating our 50th year in the music business this year with our company. And we we put a book together of the signature songs for each artist. And we realized that I mean, we’ve had some artists like Tim McGraw had 50 hits on our label, but other artists like Debby Boone had one, you know, But she’s still on a life live commercial singing. You Light Up My Life today, 40 years after the record. So the signature song, one signature song can make a career. Sammy’s case you when you add a signature song to a signature artist. Then you have an explosion that that. That you’d love to have happen more often. I’m ready for another one right now. Like shaft. Shaft was one of those, you know.