Interviewer: I wanted to just start with asking if you remember early impressions of Mae West, if you remember seeing her movies when you saw them and what you thought about her.

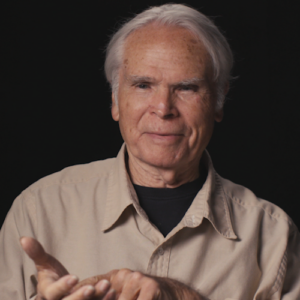

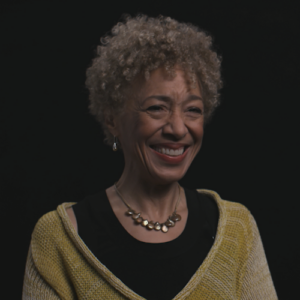

Molly Haskell: Yeah, well, I really wasn’t familiar with Mae West because I was writing about movies in the sixties and seventies. Of course, I knew her name, but there were no DVDs, there were no videocassettes, there were revivals. That would be the only way you could have seen them. And I think I probably did see them in revival, certainly not when I was young. Of course she was before my time, but I was just blown away by her. She was just unbelievable and I’ve been interested in her ever since.

Interviewer: Was there like a resurgence of interest in her in the sixties seventies?

Molly Haskell: I’m not sure You would think there would have been an interest in her in the sixties and seventies. I was. And I mean, people really weren’t. I mean, it was a women’s movement was sort of coming into gear. And so there was a lot of writing about women in the professions, in various jobs, but there was not that much feminism, feminist film criticism. So I was interested and I was eager to see her films and analyze them and make people aware of them. But I think she she was such a strange, wonderful, weird anomaly that I think maybe most feminists probably didn’t know what to make of her. I mean, she wasn’t exactly their idea of what sexual liberation would look like.

Interviewer: Well, let’s talk about the early thirties when she was sort of coming into her own Hollywood. Could you sort of set the stage for that? What kind of films were being made at that point as far as the transition from talking scenes to talkies?

Molly Haskell: The early thirties was a wonderfully freewheeling time because talkies had just come in. They were importing, they were getting actors who could speak. They were adapting a lot of plays. The movies were noisy. There were newspaper movies, gangster movies, New York City movies. So it was a sort of a wide open time. And the studios hadn’t really kind of solidified their power in a way that they would. So they were remarkably open about sex and violence and, you know, all sorts of things that would later be prohibited. So you had stars like Barbara Stanwyck, Baby Face, where she sexually moves her way to the top of the company and Garbo and Dietrich and Mae West. Well, earlier even, I mean, the early thirties was really in some ways a continuation of the Spirit of the twenties, which was the flapper era, the postwar time. And you had people like Clara Bow, who was the it girl. So there was a lot of sassy, even salacious stuff in the twenties that would make its way into the thirties and the early thirties. You also had women screen women directors, even Dorothy Arzner and screenwriters like Anita Loos and Frances Marion, who were writing about modern women. So that spirit went into the early thirties. And when we look at them now, we can’t believe what they got away with because we’re so used to the movies made under censorship from 33 on. You know.

Interviewer: I think the term pre-code is a little confusing. Can you sort of lay out what that means?

Molly Haskell: We talk about the early thirties is pre-code. Well, there had been censorship of one kind or another all the way through movies. They were people, religious groups, particularly even women’s groups were alarmed at what was going on in Hollywood, the scandalous doings of Hollywood and the movies. They were a bad influence on the young, that sort of thing. So there were local groups that protested and this kind of thing, but nothing had been institutionalized then. And it was actually in 1930 that the production code was written by some Catholics, and it contained the prohibitions that would later be enforced, which was against the undue violence and nakedness that was prurient foul language, evil. Of course, the morality was usually morality referred to sex, which referred to women. So women’s sexuality always was first and foremost as having to be contained. But and of course, one of the most famous prohibitions was about marriage that you couldn’t show a man and a woman, husband and a wife sleeping in the same bed. Twin beds. And I think you had to have one foot on the floor if you were in the bed. So, you know, crazy things like that. So these were written and it was a very well thought out. It wasn’t just a sort of slapdash thing. Then in 33, 34, that’s when the outcry grew larger. William Randolph Hearst and even Roosevelt said maybe there should be some kind of censorship. So the Motion Picture Association, as it was then, got Joseph Breen to oversee the production code. So now movies had to be submitted before they were made, scripts submitted before they were made. And he would go over them. And you just imagine him and his panel sort of, you know, sort of drooling over these movies and movie scripts and saying what could pass and what couldn’t. And so that was what happened. And so and that was basically 33 when it was really began to be rigidly enforced and can.

Interviewer: You. And this is sort of a big question, but can you sort of explain the evolution of what happened for female characters from the thirties in the 40 to 50 sixties? Like what? Is there a way to explain that?

Molly Haskell: Well, the treatment of women, I think, always reflects changing mores, changing time. So and also there are periods of liberation and then backlash is cyclical. It always goes like that. And of course, now we have as wide open as it could possibly be. Nevertheless, that that’s not always necessarily a good thing for women. So there’s a paradox there that the liberated screen is not liberated really in an equal way. Well, so let’s say the thirties. I think one thing that happened with censorship was movies became very imaginative. I mean, a lot of the scripts had to allude or so suggest, without being lewd or without being explicit. So you had things like screwball comedy, which was great for women because you had these equal partners and women were giving as good as they can take, but verbally. So that was one reason. And also women, it became just less fashionable because of the production code and censorship for women to be sexual creatures. So they became romance. They were more romantic, and that wasn’t such a bad thing. They had they actually in some ways had more authority in the thirties and in screwball comedy and even in film noir of a different kind, the femme fatale, various forms of them that also there were always, even though and I made the point which was resisted by feminists when Robert came out in the seventies, that women had actually been better off under the studio system than they were in the wide open seventies and the independent cinema that came then because women constituted not just the largest share of the audience, but were considered the decision makers as to what movie a couple would go to see. They had these women were paid as much as men. The stars are paid as much as men. They chafed under the studio system, under having to being typecast and having to play the same kind of person over and over again. But still, they really were given a lot of latitude. And so when you when you look at these movies, so then in the fifties, the this the laws began to I mean, it was really late fifties and the Doris Day Rock Hudson films, you still had repression was firmly in place. Women were still virgins. But gradually the stage loosened and the sixties became more freewheeling. The interesting thing that happened, I think, is that in the late sixties and early seventies, we had this terrific sort of not even a renaissance, just a sort of a kind of glory day of independent cinema, because suddenly there was money from the studios that could go to and it was sort of on a European style auteur cinema directors like Coppola, Scorsese, SC Altman, Brian De Palma, making the kinds of films they wanted to make however they could. They could sort of thumb their nose at the studio system. They didn’t have to make movies for women. Women weren’t They didn’t care if women were in the audience or not. And the films reflect this. There really are fewer paths for women in this period of sort of movie liberation than there were in the older days. Now, I think things are changing. I mean, it’s considering how much breath has been wasted arguing for better women’s parts. It’s taken an awfully long time, but I think now there are substantial number of women behind the camera on screen. The studios are changing, but they know they have to do something. Diversity is being written into contracts. So I think things really have changed. But and we’re seeing the fruit of that now. The twenties and early thirties were were sort of more open. The studios hadn’t sort of become hardwired for a certain kind of film genre and so forth. So there were quite a few women. Lois Webber, writing and directing in the Twenties, approached social issues like abortion. There were a lot of movies about women having just. There’s one called The Silver Cord. I just saw a known film with Irene Dunne, where she is a botanist, and she’s marrying Joel McCrea, an architect, and his doting mother is horrified that she’s going to continue working. And so the whole film is this argument between the mother and Irene Dunne, and Irene Dunne comes out the winner. So there were plays. A lot of these were adapted from plays. There was a lot of talk about about women, professional women. So you had Lois Weber, then you had Dorothy Arzner, Frances Marion, Anita Loos, all writing about women. You had a lot of women novelists writing about women’s issues and women’s and magazines, and then it all sort of went underground.

Interviewer: Let’s talk about the kinds of actresses that were were rising to fame in the early thirties. You know, And I was thinking Garbo. Dietrich West, I guess. What were their traits? How were they becoming stars?

Molly Haskell: They’re the stars of the early thirties. Well, the most, probably the most well known and the most megawatt age were Garbo, Dietrich Mae West, to a slightly lesser extent Stanwick. Other of the stars that people forget in that period are Irene Dunne, Loretta Young. They were making films about working women, but I think Mae West, Dietrich and Garbo are sort of in a class by themselves, and they created persona with the help of Dietrich, with the help of Sternberg that sort of transcended any character. And they were whirly all three and different ways were whirly. I think what’s interesting about Garbo, Dietrich and Mae West is all of them are kind of laws unto themselves. This is what they share. They’re sort of bigger than any plot, than any any male partner, anything. I mean, it’s one of the reasons some of the men are weaker in their films is they are so big that there’s nobody that can sort of stand up to them so that that’s who they were. There were these outsized persona, but there were very different. Garbo was spiritual. She was she it was the intensity, the romantic intensity. And love was in some kind of almost ethereal. Whereas Dietrich was much more sensual, sardonic, sort of impudent, world weary, even very European. In fact, there was something vaguely European about maybe not Mae West, except in the sense of her libertine nudes. I was astonished to learn that performance was what she became was really in her DNA. Her father was a prizefighter. Her mother was a model who wore model corsets. She started performing it, I think, aged seven and some kind of church thing. And then she actually went professional at age 14, and she began and it was extraordinary about her. She was her own writer, her own producer, her own director. She did it all. And I think she’s never been given credit for this. So she was creating this persona as she went along. She was very influenced by male impersonators and female impersonators. So she incorporated these into her act. Then she did this play called Sex. So you have to remember that there were there was an outcry from the beginning. I mean, she was always going to be controversial. So this was mid twenties. So they actually raised that there was enough complaints that the officials raided the play hall them off to the jail, which was the Jefferson Market lot, which is now the Jefferson Market Library right down there in the West Village. And she could have gotten off with the van, but she didn’t want to. She wanted to go to. She saw this as a great publicity coup. So So she went to jail. They send it to Riker’s Island. She would done with the head of the prison and his wife and all this. Actually, the jail experience comes out, comes up in several of her movies. She knew her way around the jail. So she came out of that. Then Hollywood came calling and that’s when she began the great films of she done him wrong and I’m No Angel. And and always I mean, think she understood, which I mean, she’s just she’s like an anomaly. She’s it’s almost a freak. She’s like a unicorn. She’s sort of half man and half woman. And she plays off this she power and she’s a parody of sort of unbridled male sexuality. She’s like standing sexism on its head because she goes after these sort of male bimbos. You know, what would be sex objects for men? It’s all done in this kind of wink and playfulness. Everything about her, this movement, the swagger, she the movement, she acknowledged owing to female impersonators. And it was like she contained multitudes. She was it was it was all humorous. It was all it was sort of a joke. And yet somehow that was something. Heartfelt in her as well. So I think she’s she’s like the opposite of Garbo in some ways. And yet there’s a kind of deep down similarity because Garbo was all spirit and transcendence, and Mae West was all earthy and Brooklyn and pull them up by the bootstraps and sex who not need more. One man is not enough. And yet she wanted love, you know, she wanted she wanted to have a Cary Grant says to her, and she got him wrong. You just don’t have a soul because she’s a gold digger and she’s got all this. All jewels are hanging everywhere. And she just looks at him. And in the end, of course, she does have a soul.

Interviewer: You know, the androgyny. And you know, I love these. She’s the unicorn that the gender identification is really interesting.

Molly Haskell: If there were if there was ever anybody that was gender fluid, I mean, transgender. But Myra Breckinridge was sort of an homage to Mae West. So, yeah, I think she was always a favorite of of gays and I’m sure of transgenders that we didn’t know at the time. And it was sort of camp. And yet it wasn’t just camp. It wasn’t just irony. There was sort of more to her than that, I think.

Interviewer: You know, because Dietrich has also been called a androgynous one.

Molly Haskell: Traits that Dietrich Garbo and Mae West all share is androgyny. I mean, you have Dietrich in a in a tuxedo in Morocco, and there’s something very masculine about Garbo, and so is Mae West. And I think in a way, when they say when their star faded, when they became what was called box office poison, Harry Brandt, the theater owners labeled them box office boys. And it was because they were this outsize thing was no longer in fashion. It was a depression. I don’t think movies addressed the Depression directly, for the most part because nobody wanted people that were in the Depression and want to look at movies about the depression. But what they wanted to see was something a little more realistic, a little more down to earth. The three are so outsized, are so laws unto themselves that they’re hard to play with. You can’t have an equal, a male equal. The men are have to be satellites because they’re just so. Outsized. And so you have. With Garbo. I mean, Robert Taylor is almost, you know, as beautiful and as she is. But still, for the most part, the men are not as interesting or they don’t have the roles that they have. I mean, I think it’s interesting that Mae West played with W.C. Fields in My Little Chickadee. That was 1940. Paramount had let her go, so she was and she was you know, this is the other incredible thing about it. She was 30 or is it 40? Wait a minute. Yeah, 40. She was 40 in 1933. She had one in 1893 40 when her two great films came out. So that did. It was like she was not only was she sexless in the sense that she wasn’t one sex of the other, she was ageless. So she’s I don’t know what, 47 and and she’s still the love interest in my little chickadee. And you would think that she and W.C. Fields would be a great somehow great chemistry. But they aren’t, because they each has their own sort of raison d’etre. Each has their own persona. And they W.C. Fields has satellites in his films and she has lines in her films. So she has kind of leading men that revolve around her. And one is never enough and that sort of thing. In fact, I think what’s interesting is Cary Grant pretty much does hold his own against her with her. And I’m no angel, and she done him wrong. And it’s because he has this light touch and he he he’s sincere. And yet you feel that he’s sort of in on the joke as well. So it works beautifully. But I mean, I think when he became a big star, I don’t think it would have worked. So she caught him at the right time and she took credit for it, even though he was in Blond Venus before. So.

Interviewer: You know, I’m really interested in comedy as a sort of force for, you know, this isn’t feminism at this point, but this is sort of proto feminism. How is comedy helping to sort of push forward ideas about gender equality?

Molly Haskell: Physical comedy generally has not been women’s domain. That’s true. You look at the silent comedians like Chaplin and Keaton and Harold Lowe. They’re all male because they represent or Laurel and Hardy. They represent chaos and disorder. And women want order. But I was recently somebody brought to my attention DVDs out with Zasu Pitts and Thelma Todd. They were a comedy team in the early days. And these short films, they were it, and they sort of had each other’s back. They had come to the big city or someplace where they were going to make it big, and if they didn’t, they were going to try anyway. So it’s kind of astonishing. There were, you know, dozens of these shorts of these two women and they sort of speak to some of the some of the women teams today in some of the television and various series. So I think women traditionally. With the anarchic thing that comedy represents was something that was thought to be mutually exclusive with the women’s domain, the domestic domain and order and all that sort of thing. So I think it’s been very it’s been exhilarating to see women in Mae West, in a way, was like the first performance. She was a performance artist. That’s what you have to see her as, because she was always performing in her films. I mean, she wasn’t really playing a character. She was performing this mythology of who she was. And so the performance artists are doing that and sort of blowing holes and and the stereotypes and the expectations of women. So I think it’s this anarchic and also the impolite ness, being angry or being foul mouth all of these things that were not ladylike, not womanly arts now is sort of acceptable and and women are doing it all over the place. So I think and I think you have to see Mae West as some sort of forerunner for that.

Interviewer: Also, the verbal, the wit and that kind of comedy is a way of displaying intelligence now.

Molly Haskell: Yeah, Yeah. The one liners are just extraordinary. I mean, people quote them all the time without even knowing where they came from. And she coined one after another of these double entendres and they’re just fabulous. So, yes, you always are intelligence that that’s another thing I think we have. We sort of think that the women who were sexually defined, let’s say, in the early thirties were somehow because of that passive and and languorous or whatever else we associate with women’s sexuality. But hers was not like that at all. It was sort of upfront. It was caustic. It was playing around with all the possibilities on her terms. She she didn’t she wanted a man who could take his time. She was in and she was defining sex in her terms in the way that men had always done it. So, I mean, it had to be revolutionary.

Interviewer: Yeah. I mean, there’s an interesting idea here is whether or not it is hard for you or me to answer. But if men actually found this sexy and desirable.

Molly Haskell: I think another reason we didn’t come to Mae West right away or came late was Buika and why she wasn’t seen or revived that much in the late sixties and early seventies when people were getting excited about film, was that men had not straight men had not sponsored her. She’s I think she must have been a little unnerving. They had to think it was funny. They had a laugh, and yet at the same time it had to make them uncomfortable.

Interviewer: You know, she sort of famously melded in. She was that person her on screen offscreen. She sort of was Mae West. Is can you compare that to, you know, Garbo Dietrich? Was that unusual?

Molly Haskell: While Mae West was a performer from day one. So I think it’s it’s it’s completely natural that she would have been Mae West both on and off the stage because she was developing this persona, this mythology all the time and adding to it. And I mean, she came out of vaudeville, which is a whole other thing. She was. And she’s she’s incredibly. There was a scene in My Little Chickadee when she’s on the train. They banished her from the town because she’s so immoral. She had an illicit affair with a masked man. And so the Indians are coming, and she needs a gun. And so this guy at the other end of the car throws her a gun, and she catches it like that and throws him now. And she is like that. I mean, she did that. It’s one take. You can see she’s doing it. So, I mean, she is quick physically as well. And this is comes out of her that that theatrical training and Garbo and Dietrich were different They were. Icons. Of the cinema who in a way they were like Cary Grant in the sense that there was this extraordinary persona on screen. And I think they tended to shy away from it offscreen, and they knew enough to. To be discrete and to be. To preserve, to somehow nurture and preserve the persona. But it wasn’t by Dietrich. It was a kind of a I mean, she wasn’t a house feral in the sense that she was extremely domestic, but but she liked to cook and she’d like to treat people to her cuisine. And maybe that was a performance, too. But that’s what she did. And Garbo, of course, famously it was shrouded in secrecy, and that’s the way she preserved her mystery.

Interviewer: Great. You know, I was just thinking about that train scene that you mentioned, Carrie. It’s sort of like sort of a girl day. And there’s this whole exchange where she agrees to marry him, and then some woman from the back of the train comes or some social from comes and said, Oh, good. Now you’re literally says, now you’re now you’re okay, now you’re okay. And that’s sort of 40. So that sort of reflecting, I guess, that time of what needed to happen in movies. Can you talk about that function of of marriage and how the censors especially wanted that to be included?

Molly Haskell: Well, in my little Chickadee, she has this faux marriage to W.C. Fields to redeem her in the eyes of the townsfolk who banister Bannister. And this was a very much if even in that film, a lot of her double entendres are sort of toned down. They’re not quite as racy as they are in the earlier films. But here she has to be married, even if it’s a pretend marriage, in order to allow her not just within the plot to return to the town, but just because otherwise it would be a bad influence if she and that was true in movies in the Far East who had to be married. And also you couldn’t divorce. So it was a good thing she had the fact that she had a phony marriage so she wouldn’t be divorced. She could marry again. So. But yeah, it was very it was quite rigid about marriage and divorce.

Interviewer: Great. You sort of said this already, but I think it’s important to say about women being the primary audience at this time and how whether these characters were May was somebody who was meant for a female audience or not or or was she?

Molly Haskell: I think Hollywood was feeling its way in the early thirties and they didn’t probably have focus groups and, you know, sociological surveys. So I think they were playing it by ear, seeing what would play well. They were greedy. They were trying to make money. So if somebody I mean, Mae West absolutely redeemed Paramount. Paramount was going bust and then she was the biggest star in 1933. She had the second biggest salary to William Randolph Hearst of any person in the country. So it was all how it played. And so I think they they wanted women in the audience. Women were always considered the major audience all the way through until until the sixties and seventies. So they wanted to appeal to women. And if if she had an appeal to women, that would have been the end of them. So I don’t know exactly how it played out demographically, but gradually they were too rich for people’s blood and the depression. And I think that’s why those three stars faded.

Interviewer: I think. This is from your book. And if I’m not if I’m incorrect, you can tell me. But there is a there’s a line about her, her taste in men. I guess this is really specifically kind of later in her life. Also, the the musclemen that surrounded her and she got older. Can you talk about that and what it said about her?

Molly Haskell: So at one point she says, I’m the sweetheart of Sigma. At one point, she says, I’m the sweetheart of Sigma PSI. So what? So this is her role is to surround yourself with men, to sort of play off one against the other. And the fact that there’s all these musclemen is what gave her this kind of really odd off center image. And what were these what was she doing with all these musclemen? It was sort of a gay trope, and yet it was not quite that either. It was a woman of infinite. And she was she was both omnivorous and insatiable and indefatigable. I mean, she was just sort of a monster of sex, but but not a monster in a negative way and a sort of playful, self-mocking way. And she was actually somewhat prudish. Apparently, she didn’t drink or smoke. In fact, she didn’t want to make a film with W.C. Fields because he was a notorious drunk. And she says if he comes on the set inebriated, I’m off. So he did Only one day, did he? And they they called them off the set. So she was able to finish it because I think she was she was very careful of. I mean, she had it had a somewhat religious background, churchgoing background. And I think she she really played up the salaciousness as as just sort of this one giant glorious joke.

Interviewer: Was there anywhere for her to go? Anything for her to do after this? These laugh movies and that laughter my little ticket is anything. Where else could she have gone? Or options?

Molly Haskell: The fact that Garbo, Dietrich and Mae West were so well known and the roles they played so outsized, they were icons. They couldn’t shift gears. It wasn’t possible. I mean, they tried to with Garbo to make an ordinary woman, and it didn’t work. And Mae West could couldn’t couldn’t be ordinary in any way. I mean, there probably would have been roles for her, but not starring roles. And she didn’t want that. I don’t think she ever wanted that. I mean, where they tried to give her a role. David Selznick offered her the role of Belle Watkins in Gone With the Wind against the Marine Officer’s Wishes. They didn’t want that at all. And he bravely kept in the house and it wasn’t a big enough role for her. So she wasn’t going to go out as a supporting player. That just wasn’t in the cards.

Interviewer: Did she feel very competitive with other actresses? I mean, any.

Molly Haskell: I think Mae West was just sui generous. I think I think since the films reflect what she wrote and who she was, she was just she wasn’t a woman in competition with other women. Yes. The straight laced women would walk to the other side of the street to avoid her. That was a given. But she’s always got some sympathy for some innocent woman that she’s trying to take care of. The greatest thing, I think, is her relationship with the black women that she plays with. There’s this incredible rapport and it’s like they both they all have this kind of boisterous humor at men’s expense. And they just laugh and laugh and get off on each other. And it’s just a glorious thing to see. But she’s large hearted. You don’t feel that she’s out to get other women and she’ll if she finds out the man’s engaged, she’ll send him back a fish. She’s throw the fish back in. In fact, in. And I’m no angel. They’re the society women who come to see her circus show. And one of them who’s engaged to the guy who she will have a little fling with is horrified and just hoity toity. But the other women think she’s great. They come to our dressing. She’s great. They accept. They know she’s sort of lower class and louche. But but they think she’s great. So it’s a very vibrant and changing relationship. There’s nothing rigid. The thing is, though, I think she has to be a star and that’s all there is to it.

Interviewer: Do you think she was trying to make a statement with those scenes with the maids?

Molly Haskell: I don’t know what was in her mind with the way she used blacks, but it has to be intentional because it’s not. No one else is quite like that with black servants in movies, and they are more a decamp than servants, although she also give them hell if they linger. And you know. But she is so playful, the relationship is so playful that and also her even her singing has a kind of black bluesy aspect to it and her take on sex. I mean, the blacks were always much more frank about sex than white, uptight white people. And there’s something black in her, and this is why she contains whirls. It’s nothing black. There’s something Brooklyn, there’s something a little bit pious even, and bawdy and all the rest.

Interviewer: You know, I just thought of a question. I haven’t we haven’t asked anybody because I have to do with class. A lot of people have been talking about her as sort of maintaining that accent as a way of claiming that working class background and sticking with it. Do you think that she had to do that? She couldn’t. She had to retain the working class ness If she was going to talk about sex that much, It sort of both had to go together. Yeah.

Molly Haskell: Yeah, that’s a good point. I think she she luxuriate in her and Brooklyn background, but also the lower class. She also emphasized the lower class and she always had herself pitted against the swells. And she didn’t speak good English. And she you know, she she she spoke black English in a way. It was black and white. And I think she needed that to have this sexual persona. It wouldn’t have worked. She couldn’t have been this swaggering woman of appetites if she were upper class. It just that contrast had to be in place. So in a way, that’s another thing that sort of goes out. After the early thirties. But I mean, movies are always class. I think they’re much more class conscious than we ever give them credit for being a talk about. We sort of are always uncomfortable with that aspect, but it’s very important, very important.

Interviewer: You know, Mr. West career is on the decline. How do we understand the rise of an actress like Shirley Temple? What does it say about where society is going, that she’s sort of the next star.

Molly Haskell: Or Shirley Temple? The irony is she’s sort of the reverse mirror image of Mae West. I mean, she’s sex, but it’s coming in the back door. I mean, the good ship lollipop is like kiddy porn. She’s prancing around among these men and rubbing her tummy up against them. It’s just and she did this these shorts called Baby Burlesque, where she was burlesque ing Dietrich and Mae West. So she’s very much of a part of them, only it’s done in a much more covert or apparently covert way. I mean, Graham GREENE called the studios on the way on this treatment of Shirley Temple, saying it was absolutely salacious, it was dirty old men, you know, drooling over her. So it was it was Mae West coming through the back door, a pint sized Mae West, and in a way, in our own way.

Interviewer: That’s so funny, because you’re totally right. But nobody said that she was completely sexual and it’s almost so much more inappropriate.

Molly Haskell: Yeah, I wrote a piece for The Guardian about that last year, but yeah, about about nymphet. Nymphet worship.

Interviewer: There’s a phrase that you wrote that I just love, and I would just love you to say it. And you’ve. You’ve talked about the double entendres, but the the master of the triple dots, I just think that’s such a great line. If you could just explain what that means.

Molly Haskell: She’s she’s always making jokes about multiple men and she and somebody will ask or something. She says, Well, it’s not the men in your life. It’s the life in your men. Of course, the famous one. Why don’t you come up and see me? So actually, she said, Why don’t you come up sometime and see me? So there’s always this leering pause, the three dots between one half of the sentence and the other half, and you’re meant to make of it what you will. And also, she’s always saying, come up. She’s it’s like she’s in this IRA that men come up to. She’s not low down trash. She’s up there and they have to kind of climb the stairs to meet her grave.

Interviewer: I love that You also write and this is a very good point. She’s always winning. She that’s she’s she’s always on top.

Molly Haskell: She has to be a winner. That’s who she is. And that’s maybe the great thing in her movies. But it could also be a defect in the long run because it means she can’t really play vulnerable. She can’t play. She can’t let anybody else overcome her. Or I mean, she even with W.C. Fields. She comes out and she looks frumpy sometimes in that film. She has this house dress she’s wearing and then later on he’s wearing it looks like the same house dress. They’re both sort of frumpy bears were walking around. But she even gets the best of him. And that’s not easy to do with W.C. Fields, but and also Grant. But but she manages that. There’s a kind of equilibrium with Grant. But but she’s not going to. He says something about and I’m no angel. He said, Well, I think this is their reunion in the end. I think we should go some further somewhere for a rest. And she just weights and says, Dot, dot, dot. Who needs a rest, you know? Who wants a rest? You know? But she’s got to work him always. So she’s the aggressor. Even with Cary Grant, she’s. She’s on top. She’s the one who dictates the terms. And I think that could get tiring if you had to see it over and over and over again.

Interviewer: Well, the lack of vulnerability starts to feel like you. Yeah, You’re watching. There’s something about an actress that you want to feel like. You see that vulnerability, right?

Molly Haskell: Yeah. I think that her lack of vulnerability means you don’t. Well, I hate that word relatable, but you don’t relate to her. Identify with her in the way you do with women who are who who expose a weaker side. She’s so self-contained. I mean, just the fact that the male and female, because usually you have women and men, but she contains both. So there’s no alternate, you know, there’s no one for her to bounce off of or against because she’s it’s all in her.

Interviewer: Yeah. I mean, and this other idea that that women, you know, her big thing is women is fighting against the idea that women need to be punished.

Molly Haskell: On the other hand, I mean, the fact that the other side of that lack of vulnerability is she doesn’t have to get punished. She doesn’t have to get chastened. She doesn’t have to pay for her since she has deniability and she done it wrong. She’s all these bows of hers involved in these very salacious criminal activities. But she sort of has deniability if she saw it. I mean, her on one weakness, of course, is money and gold. So but in the end, she always is always redeemed. But I think even in pre-code films, she wants she has to be redeemed and she has to show she has a soul. So she wins all the way around. You know, she can be she can be sort of playfully dirty, playfully even go to jail. She goes to jail, but somehow never sordid. But it’s a it’s a really tricky when you think about it. It’s quite a balancing act and it can’t go on forever.

Interviewer: Great. I want to return to what we were saying the beginning about feminism in the seventies and how they grapple with a character like this. Because when I approach her and read about and learn about her, she seems like a very feminist figure and a subversive way. And I’m wondering in the context of the feminist movement in that time, how feminist grappled with somebody like that.

Molly Haskell: In the seventies when we were. Well, how much we’re examining literature, movies, everything. I don’t remember any reactions to Mae West, but that in itself, the silence may say something in itself. I just don’t think women knew what to make of her. But we’re in this moment, then, when we are emerging from sexual repression or when we’re still a little bit repressed, and we have this vision of this utopian vision of sexual equality, women are not going to wait for men to call them. They’re going to make the phone calls. And then here comes this woman who’s. Who’s really about a kind of male sexuality that that is objectionable at the least. But when you look at it now, it seems so gentle compared to what this kind of Internet porn and hooking up and the lack of romance in movies. I mean, in a way, she seems like a kind of romantic figure. So I think the context changes. And so the context was one thing in the seventies, and she was almost too too good to be true in some ways. And she should have been more revered and more talked about. And I hope that will happen. But but you can also see why there’s resistance on the part of both straight men and straight women To her. She just don’t quite she doesn’t fit into any of the categories.

Interviewer: Do you think she’s a force for feminism?

Molly Haskell: I think she’s a tremendous force of feminism, whether she called herself on or not. And I think she did. I mean, she I think she was sympathetic. I think she did display are expressed sympathy with feminism, but maybe like so many didn’t want to be called a feminist because she had this idea. This really was after all, the other thing in the twenties was suffrage. So you had two different kinds of freedom on the part of women. You had the political fight for political for the vote, which we got in 1920, and the suffragettes were fairly stern and sort of they were all against alcohol and all that. Then you had the sort of party feminists who were going out and drinking. So there were these two strands of feminism, and so they couldn’t help anyone like Mae West. All of these women could not help but be affected by that.

Interviewer: That’s a really important point. Yeah, Well, you know, one of the other interesting themes about her in her life is the idea of aging. And she, you know, goes she’s in her eighties and she’s on a couple movies and or she’s on the radio or some TV or whatever. She’s older and she’s still playing this very sexual role. What do you make of that? What is your response to it? We as a society really have an issue with women expressing sexuality, you know, at 85 years old. Is she trying to push that laugh envelope with them?

Molly Haskell: Yeah, it’s interesting to speculate what she what she was doing in these films where she’s obviously old. They hadn’t been making films for ages is but is still is still playing the sex card and is that is that is that an up for is that opting for a certain freedom is she pushing the envelope for women’s sexuality at a later age. I think that’s I mean, we have to face the fact that that film is a visual medium, that that’s all there is to it. Women age faster than men. Visually. They have to deal with that. And I think we are uncomfortable, and I think rightly so at the sight of and I don’t older people don’t want to see it. It’s not just younger people ought to be. They want to fantasize themselves as younger. So I think it’s it’s really a it does damage to the fantasy of my was I think it was probably a mistake for her to do that. But they all did that. You know, all these actresses played sort of parodies of themselves and they just couldn’t stay away. So I think we just have to put that into the category of of great stars wanting to want one more moment in front of the camera. So Sunset Boulevard and this is their Sunset Boulevard.

Interviewer: Yeah. I mean, I guess in thinking about her legacy, I mean, I don’t know. Do you know there anybody today that you compare to Mae West or think is doing what she did?

Molly Haskell: I just think RuPaul and somebody like RuPaul is the only analogy I can find. It has to be somebody who combines who’s gender fluid in some way, because that’s really what she was. She was we didn’t use the term then, but Avant La Lettre, she was gender fluid. So it would be drag performers. It would be. But also women just talking about their sexuality. I mean, whether it’s Amy Schumer or whatever, comedian, it’s a train wreck of their sexuality. Of course, it’s all dark and bleak now. It’s getting getting wasted and having a lousy hookup. So there’s nothing now. I mean, there was something strangely wholesome about Mae West. I mean, that was another combination of wholesomeness and and raising this. And she could somehow bring those two together. But now I think a lot. I mean, this is what’s. Sort of grim about women’s sexual liberation is that it has created this world in which men are hooked on Internet porn and expect a certain kind of free sex from women. All sorts of I think all of that. I mean, they’re also. Great opportunities for women. I’m not saying they wouldn’t want it otherwise. They wouldn’t want to go back to repression. And yet, once again, sexual liberation has not fulfilled its promise to women.

Interviewer: Do you think there’s a way that women performers today have to sort of choose between being funny or being sexually desirable? And May was doing both, but.

Molly Haskell: I think there’s always a division between being sexually desirable and funny. I mean, sex is not funny. If you have an erotic scene and it’s funny, then you’ve made a mistake. There are a lot of women who are sexually, let’s just say, sexually attractive and also funny. But they’re not comedians like Carole Lombard or Irene Dunne and all the women in screwball. They’re funny and I think sexy, but not sexual. It’s not a direct sexuality. And I think Mae West is not real. I mean, the great thing what was one of the biggest the great joke of all is that we are it’s a given that every man that sees her, it just wants her. You know, she’s so desirable that men are going crazy for her. And and this is the joke. And she’s an I mean, she’s not desirable in any conventional way. I mean, there may be some fantasy that has Mae West that it’s some, you know, perverse fantasy that has Mae West at its center. But she’s certainly not desirable. First of all, I mean, she’s she’s just too powerful. She’s actually rather short, but she’s just big. And that’s certainly not traditionally male appetite is after. So the whole thing is she’s playing at being the most desirable woman in the world as part of the performance. She I don’t think you could say she has sex in a way, and comedy in a way that women now don’t. I don’t think ever. You had the two together and men. And I think if you have a male comic, he’s usually not sexy while he’s doing his his comedy.

Interviewer: Is great. I mean, so she’s primarily a comedian, but she’s.

Molly Haskell: Primarily a comedian. Exactly. And a performance artist.

Interviewer: Great. Why do you think we need to know? Why should we make a film? Why? Why do people today. Why should girls know about Mae West?

Molly Haskell: I think it’s fantastic that you’re doing this. In fact, with thinking about Mae West made me think. Why have why isn’t this been done earlier? Why haven’t we been talking about her all this time? And I think once again, it’s because she’s so complex, her persona is so complicated and it doesn’t fit into any category. I mean, every other even Garbo and Dietrich are more easily categorized than Mae West. It’s just too she’s too much to handle. As she often says in the film. She’s too much to handle. She’s too much for any one person. And we found that with her, I think, as an audience. But I hope this will bring her to the attention to people. I think, God, she is. She’s got. Just in terms of the wild possibilities of female humor.

Interviewer: Yeah, I think people sort of post the parody they write. Yeah, yeah, yeah. I really see that. There’s so much depth to what she was doing.

Molly Haskell: I mean, she’s so much a person. I mean, just. I think that’s why her relationship with the blacks, there’s something so elemental in this kind of boisterous rapport that they have. It’s soulful. It’s. It’s soulful. And funny. Just one little point. Another thing about her and this might be a repeat about another thing about her. That makes her. Unique and not a potential partner in romantic comedy is her self-possession. She owns herself in a way that no other star that I can think of in movies does.

Interviewer: When it comes to the censorship of her. Do you think that her persona was just a threatening one to men? I mean, this this idea that she was her own woman and and she joked about sex and took men down a peg. Was that threatening? Was she someone who needed to be contained?

Molly Haskell: I think many women found her objectionable. I mean, the religious religious right was strong then as it is now. But I think it was men primarily that found her, I think must have found a threatening. It was William Randolph Hearst that really blew the whistle. Of course, he was sitting there with his mistress. But somehow Mae West was immoral. But they could use the morality to cover something that was went deeper. I think that there was something really subversive about her sexuality, her purported sexuality, her appetites, all of this. I mean, men were looking at themselves in a woman and through a woman’s eyes, and they were not comfortable.

Interviewer: Great. And what we haven’t really said or maybe you said, but we should emphasize that she was writing her material. And that is a big difference to the other women.

Molly Haskell: One of the most distinctive things about Mae West, and it bears repeating, is that she wrote her own material. Another example of how she owned herself. I mean, Garbo and Dietrich and all the others were in scripts. Well, mostly they were written by someone else. Mostly by men, but not always, but written by someone else. Directed by someone else. She was her own writer, performer, director, her wit. Therefore, you sort of couldn’t blame it on anyone. She was. She was the target. She was it. So and I think the one liners were like, well, sort of brilliant and beautiful locker room jokes, the kind of things that men do to each other when they’re sizing up women and that women find so offensive. She was doing that to men. She was turning the tables and they didn’t like it.

Interviewer: And the writing of her own material meant she had power.

Molly Haskell: Right. Writing her own material meant she had power. And she insisted on it. And she would. She would have it in her contract. She would go into each film and demand it. Even when she was let go from Paramount and made my little chickadee. She didn’t have the power she’d still had. She insisted on it or she wouldn’t do the film. She wrote it and she out wrote him. I mean, he had some great flowery phrases, but she had the one liners.

Interviewer: One thing I wanted to follow up on, something that you had said about how older people want to fantasize of themselves as younger. And so they don’t want to see an older woman being sexual on screen because it shatters that fantasy. I just sort of want to.

Molly Haskell: I maybe speaking for an older generation and saying that I think older people do not want to see older people having sex on the screen. We want to fantasize younger, but always Children have been horrified of their parents having sex. Students don’t want to hear dirty jokes from professors. When you see an older people on the screen, you think parents. In addition to that, you see if they’re honest, you see leathery skin and spots are you see facelifts trying to stay younger. Why do they have face if everybody wants to see older people as they are? A lot of people have facelifts. So I think and in a way, you see a facelift and you’re more aware. I’m running out.

Interviewer: No, that’s okay.

Molly Haskell: You see a facelift and you’re more aware of the age than you are if the person looks as let themselves be normal. I think there’s some actresses that can get it. Like John Moreau could go on and for a long period of time, some can. Some actors and actresses can go on longer than others. But this applies to men, too. I had students who thought Harrison Ford was too old to play romantic in a movie. So it’s not just I think it’s not just me. I mean, maybe that will come. Maybe we will be. Since we’re living so much longer and we have life in us for so much longer, we will get used to images of that life and us longer. And I hope that happens.

Interviewer: Yeah, I mean, I think one of the things about me that I think initially I felt a little disappointed by was she’s this strong, confident person in her early years and you wish that could be reflected later. And it doesn’t somehow when you’re trying to be that person still.

Molly Haskell: I think there’s an argument either way about actresses or actors going on the screen when they’re much older. On the one hand, we love them, they’re great people and they have careers and they want to keep going. On the other hand, we have this image of them. If we’ve watched them gradually get older, it’s a little bit easier to take. I mean, we don’t want to think of our mortality. Let’s say old age equals mortality. We see Mae West shrunken in some way, both physically and spiritually. And it’s heart wrenching because we want to keep aloft this image of her in her prime.