Speaker We were having dinner once with my Vanderbilt side. Uncle Freddie Field. And during dinner. Out of nowhere. He turned to my father and he said, Bennie, you’ve got a better Vanderbilt accent than any of us to.

Speaker Do you want to go back and touch on the same question with your other party?

Speaker Yell at me live. You ask me, you ask me a couple of questions.

Speaker Are you really going Manji were having having.

Speaker Well, I don’t want this to be too raw. So this is just a meme to stir your memory.

Speaker We’re talking about on what it’s like to live shadow. I got it again.

Speaker So many people on the outside. I see most of the world who don’t have incredibly famous parents think, oh gosh, it must be just wonderful to have such a famous parent. And they don’t understand what a complex thing it is. That, of course, there are parts of it that are wonderful. There’s it’s exciting. It’s unusual. There is often money involved. There is often glamour involved. That part is positive. But I would say that if I had to balance it out, it’s like 70, 30. Bad because. I don’t like being introduced as many Goodmans daughter. I can handle it now, but I find it difficult because I can’t pull away. I mean, still now as a grown up, I find it very hard to pull away from that man who I mean, I didn’t realize how famous he was until the day he died.

Speaker And I realized that his death appeared on every single newspaper in the world. That was an eye opener for me. It’s like, oh, so this is what it’s all about. He was really that big me. When you grow up with somebody, that person is the wallpaper. I mean, I didn’t grow up with Benny Goodman. I grew up with my father. He was the grass. He was a wallpaper. What did I know? This is what my life was like. I couldn’t compare it to other people’s lives.

Speaker But.

Speaker In one way, but in another way, there was always this oppression. There was always this the sort of danger of being engulfed.

Speaker I don’t know how to put it because people who have that level of drive and talent are ruthless and they’re voracious and they’re going to suck up what they want and they’re going to spit out what they don’t want. I mean, that’s how they get where they get.

Speaker And I mean, in some way, it would be nice not to make a value judgment because it’s the way they are. But, I mean, human beings make value judgments. It’s not a lot of fun to be around that.

Speaker And. It’s a very, very complex thing.

Speaker Here’s a story that will really exemplify what I mean.

Speaker I went to see a friend of mine who is going to a concert. She was in the car. Her husband and another couple. And I said goodbye. She drove, drove away. And she told me that as they the four of them were driving down towards San Francisco, they passed a marquee with my father’s name on it.

Speaker And he because he was about to appear there. And when that happened, this guy in the back seat said he couldn’t. You know what that man means to me? She knew how many of his records I have that I live for the sound of his music. Rosemary, during the hearing, she said, well, you of course, you don’t realize it.

Speaker That friend of mine who just said goodbye to us. That was his daughter, Rachel. He said, you’re kidding.

Speaker That was his daughter. And.

Speaker Was secure any support? How could you not tell me? And she said, I wouldn’t dream of telling them. I don’t introduce my friend. Rachel is Benjamin’s daughter. She’s my friend Rachel. And that’s the way I would rather be. And yet, at the same time, of course, I completely understand why people would want to introduce new very Graham daughter. So it’s like, OK, if Glenn Gould, my idol, had had a child, which he didn’t and I was friends with their child, I would probably introduce that person. Oh, this is my friend Sally.

Speaker She’s Glenn Gould’s daughter. Because, my God, I’m cool. I mean, I loved his music. So on the one hand, I completely understand that need and people.

Speaker But on the other hand, I hated living around with it.

Speaker And two little things that I forgot to ask you, one is about the stray bet.

Speaker And generally, you didn’t like to be around musicians and you can just quickly throw in the river to Marlborough and Circle was there with the Stones, with Christmas, like even that he had to get away. Right. The only exception was Mel. OK, OK. And might be more than happy because it’s a different thing. He’s a composer. And it will set him up.

Speaker OK. OK. Now a jazz musician. OK. OK. OK.

Speaker I want it in. You can also froemming about Mel. And of course then Mel became something different from all the other musicians that he’s been to because he went on to become famous composer.

Speaker Well there you go. Or whatever you want. That’s a whole long story. Let me just I just want to set it up so you could say, oh, because you proper lesson to.

Speaker Right. OK.

Speaker All the time. Forever. People have asked me. Your father hung out with musicians a lot, didn’t he? You would have always had a lot of musicians around your house parties. Never. My father never spent any time with musicians. It was just the weirdest thing. He was really private person. He was very unsociable. Most of the time, he was always busy watching that inside movie of his thing about music.

Speaker And I think music was so engulfed him that it was oppressive and cloying and engulfing to have music around him. He couldn’t have any more than he already had, which was like 100 percent. So he didn’t have musicians around him.

Speaker He didn’t have classical musicians around him. We went up once for the weekend to the the Marlborough Music Festival that Serkin had. And we spent a weekend there. We went to a number of concerts.

Speaker And I remember both of us like turning to each other in the car as we drove away. It’s really nice to get out of here. I said something and he said, I agree, Rich. That was really too much for me.

Speaker I said, You felt that way, too. It’s like, but you’re the musician. I mean, how come you didn’t like it? He said, I know it was just too much for you. I don’t like all that music. And I remember thinking that was kind of funny at the time. The only person.

Speaker There was really a major exception to this generalization about my father, although I mean, in so many ways, this man, Mel Powell, is an exception. He was a milpa, was a really good friend of my parents. He and his wife, Martha Scott and their kids. And they used to hang out a lot together. And he and my father had a very special kind of relationship. But. That is colored so much by the fact that Mel is a completely different animal than the boys in the band. Mel went from being the jazz musician who he was at a very young age, like 18 with my father to becoming a professor at Yale, to go on to being an extremely noted composer of avant garde music to getting a Pulis surprise. So Mel wanted a completely different direction, but he was the only musician. I remember my father spending time with.

Speaker OK. Perfect. Good.

Speaker Yeah. Mel doesn’t know where to go to. A guy I knew was made this great line. There’s nothing more repugnant than an old self. And Mel is just a perfect example that Mel does not like.

Speaker I mean, he you know, he says in interviews the thing that he did for four years is the only thing that people know about him.

Speaker It drives him crazy because people don’t like the music he does. It’s just too far out.

Speaker It will probably have Soopers, but just in case. I’m Rachel Eidelson.

Speaker And then if you want to say bacon and soda, we’re really well, you’re thinking of having people, like introduce themselves.

Speaker Maybe it’ll be off camera and we’ll just hear the voice. That’s why they had civil wars. They would have.

Speaker You know, John Brown is a member of the 4th Regiment. And then when you’re done saying that, we’ll be quiet for 30 seconds for Paul.

Speaker Mm hmm. So I do this looking they’re looking at you know, it doesn’t look like I’m Rachel Goodman. Adelson, his daughter on campus. Just like that. I’m Rachel Goodman, Adelson Goodmans daughter. Yes, we noticed that my voice. I’m Rachel Goodman, Nadelson, Benny Goodman daughter.

Speaker OK. You don’t know that. I mean, you’re not using that picture. No.

Speaker They weren’t particularly happy. They weren’t things I never thought of before, I’d thought about them a lot, but there was something about putting them all together and just I think it was just the experience of feeling once again engulfed by his presence. I didn’t like it. I mean, I’m I’m very happy to be doing this, as you know. And I think it’s really important. But it just reminded me how much of my life was spent like that, because these they’re so voracious, these people of that talent and that need in their drive and drive. And they they suck up people.

Speaker And I think they they often particularly suck up their children. And I’m not really sure. I mean, even though I have my own children, I’m not exactly sure what’s involved in that need. I just know that from my own, I really, really try in every every way I can to respect my children’s need for autonomy and not to need them that much. And also not to pull them on and egg them on the one hand and then go like this with the other hand, which my father was so good at doing. And I think a lot of famous parents somehow are very good at doing with their children because they’re in such conflict. I mean, on the one hand, who they see all this talent, right. That comes through their genes for their blood lineage here. They see it. They’re responsible for it in a way. And so because it comes to them, it’s them and it’s not them. Right. So they have this incredibly close relationship to the two, to their talent and their kid.

Speaker And I don’t know, I guess it’s in some way it must be the ultimately conflicted situation because they want that talent to grow. They want their offspring to to continue the tradition and to carry forward that great talent, which they’ve in a sense given.

Speaker But they don’t. Because what if the kid’s better?

Speaker And I mean and then for so long, I thought that, oh, I don’t know, like because I wasn’t a boy, it was easier wrong. I mean, it doesn’t make it any simpler. I mean, I resent the fact that I was a grown woman. I mean, that had its own kinds of complexities. It wasn’t Rudolph Serkin and Peter Serkin who and I’m no Peter’s had his own struggles to deal with. But it was really somehow I mean, the farther I am away from I guess from my father now that he’s died, the gladder I am, that I’m not playing music.

Speaker I’m just incredible that I’m not doing it. I can’t imagine I couldn’t I couldn’t have done it. And I had a lot of talent and theoretically I could have done it, but but not being who I was, not having had a relationship with. So I guess those are some of the things I was reading about last night.

Speaker How did you experience that push pull you think it is? Oh, yeah.

Speaker Well, I guess the. The heaviest one was. We did that concert when I was 21 at Sanders and. Maybe the next year, something like that, I want to worry England and I lived there that year and I did a lot of music. I found a partner that had a grand piano and I played a lot there.

Speaker And I played with some musicians whom I did for my father. And I mean, you know, and then also this part, a part of this is the naivety. I mean, I grew up playing with these fantastic musicians. And in a way, I was that good because I had so much talent and I had such musical exposure, which obviously augments the NAT whatever natural talent there is. But I wasn’t that good. And that was always part of the conflict for me. How come I. How did I deserve to play with these people? But I did so anyway. I played all that music and then I came back and I was living in New York.

Speaker And I bought a grand piano, so moving me more on the road to music. And I played this concert with my father at Music Mountain and.

Speaker Stuff. It was really getting tricky. Then my father in the and I remember this one unimaginable thing happened. We were going to do a concert. We were going to do the. I was doing a cello. The Shostakovich cello sonata with a guy from the string quartet. And he and my father and I were doing the Brahms, a minor trio, credentialling piano and.

Speaker One weekend, my father came back from the city and he didn’t bring his music. He didn’t have his music to practice. I mean, I just couldn’t believe it. And I said, Daddy, why don’t you have your music? And he just like, well, to me. None of your business. And don’t ask and shut up. And I just couldn’t believe it. And because that was so unprofessional and so unlike him. And we go, oh, my God, we began having just horrible fights about how the music music was going to go. And that’s sort of when I really began sensing that I really couldn’t play with him anymore. It was just impossible. He couldn’t. I mean, I knew I couldn’t handle it, but he couldn’t either, because we were just we were in this kind of death struggle that a parent can have with the child.

Speaker So I wasn’t showing and I was in my 20s. I was a grown woman. So. So what happened in that concert was remember I told you last night about how. I fight with him about how slow a peace ought to go. And so this is a slow move in the brahms’ and it’s a very complex thing work. The cello and the piano and the clarinet are all taking over these very slow melodic lines from each other. And I’ve been pushing and pushing that we do it really slowly. And he was pushing to do it faster. And my God is fine on stage. I mean, completely unprofessional. He started off at one speed and I slowed it down a little teeny bit when it was my turn. And he speed it up a little bit when it when he came in with his line and I slowed it down a little bit.

Speaker I mean, this was stage. Is unimaginable because, I mean, I grew up. You played professionally, right. You don’t mess around on stage. But here we were sort of messing around.

Speaker Well, it got. Little derailed.

Speaker Not horrible, but see the cardinal rule for performances, you never, never stop.

Speaker Never. You just keep going. And my father said. Why do we stop and go back from the top? He said that on stage during a concert he won. It was a really bad moment. He won. He put me in my place. He’s going to win. He’s going to dictate the tempo. And that was the end of it for me.

Speaker I mean, I’ve heard other stories where he did that to people, you know, he did on one stage and they were twins. We just the song. That said, we’re going to learn that. Right the first time they sang another song.

Speaker Yeah. Well, listen, there were there were there were moments at which he could be truly unforgivable. And those were the kinds of moments because but not only forgivable, unforgivable in a human sense, but totally out of character, because one of the things that made him so great was his iron discipline and the professionalism that kept him going. And they kept the musicians going that he played with. You performed a certain way. You didn’t mess around because you had a concert to give. So that was part of what was so weird because of what you could call it was petty. Right now, the man was really rude. It was also petty. You don’t do that onstage. But sometimes he just it was he’d slip and he’d flip and do it.

Speaker What are your earliest memories of hearing music? I remember hearing his clarinet first, remember hearing piano music. What’s your earliest?

Speaker Well, I’m sure I remember hearing clarinet first. I do remember when I was three. He did the program with the movie with Danny Kaye.

Speaker Start. So I tell you what. OK.

Speaker So I remember when, um.

Speaker I was three. He did the movie with Danny Kaye song Osborne and I, so I really remember, even though I was so young being on the set there, he took me along for that.

Speaker And I just had these vague memories of those were the sort of buildings that the actors stand around in and seeing Danny Kaye and being with my father for that. But then afterwards, what I remember most is the house where we lived on eleven forty five Korski Drive. We lived there for a number of years and I don’t remember whether I’d begun studying the piano yet.

Speaker Probably had actually. And I remember lying on this long kind of white sofa we had and he was playing what I’m sure was the Brahms F minor clarinet sonata with a pianist. And I just remember lying there on the sofa and I was a really little kid and I just saw that was the most incredible music I’d ever heard.

Speaker And I’m sure part of it was the kind of, I don’t know, joy or pride or whatever that any kid, any child is feeling, hearing her father play. I mean, I’m sure there’s a kind of universal human dimension to that. But I think that for me also, there was another dimension that I am so totally fixated on Brahms. I mean, Brahms, for me, my whole life has been maybe the ultimate composer. And I mean, it probably started off because I began hearing Sobran Brahms so early.

Speaker But I just remember being absolutely captivated by that music when I was so young and and.

Speaker I guess that really didn’t stop to tell a story about someone in your family decided you would start playing piano. There was a rule. There was an agreement. Yeah.

Speaker Okay. So I think a way like this.

Speaker My mother and my father cut a deal and said, oh, okay.

Speaker Day four to five years, the.

Speaker OK. So ask me the question, are you ready to tell me about someone had planned for you to stay?

Speaker I think that my began my beginning of play music went like this. I think that the way I started piano went like this, that my parents cut a deal. And my father, one that I would play music. Start playing piano, and my mother won the part that said I wasn’t going to have to practice because I think it was she who didn’t want me to have to practice. And so I began three or four. And in this house where I used to listen to that Brahms and I don’t remember loving lessons and I don’t remember hating them.

Speaker I just remember having them.

Speaker And the other thing that I remember is that my teacher, who was a woman, I think of singular lack of talent or inspiration or anything, would dutifully every single week she’d make out there these little line notebooks we in which you write music. And those were my assignment books. And she would. Every week she’d fill them out with what I was supposed to do with little money to sing with with the differences in the days. And I would never, ever write anything in them. But she wasn’t gonna be daunted. And every single week she’d fill them out for me to do. And I’d never fill them in. And that was the game we all played and apparently was OK with her because I kept plan.

Speaker About getting your first records. And it was just deep in your head.

Speaker Oh, by the way, you know, when any time you want me to rerun something, I mean. I know.

Speaker I remember at around 11 years old. One Christmas, my father gave me a bunch of records, and now that I look back on, it was really, I think, kind of schlocky music. A lot of it was really romantic stuff that I can’t stand working on and off with listin 40 million notes per bar. But he wanted me, I think, to be exposed to certain, I don’t know, certain great pieces of music and Foremans. And this guy does this incredible.

Speaker Ryan Lanza, the final note. And my father said to me that was a lucky day for that guy, that he played it like that. And I don’t know why. But somehow I remember that day, that that moment when he said that was an explosion of awareness for me. But it’s like I hadn’t been I was a kid. I wasn’t a performer yet. I didn’t know that there was such a good thing as a bad day and a good day when you were performing. I didn’t know that Cassidy’s who could’ve missed that note. And when my father was so awestruck with their performance, it just gave me an awareness that this man could’ve missed. And how impressed my father was and also the kind of ID he felt with the pianist.

Speaker Do you remember when you became aware that he’d written a song for you?

Speaker Well, when you heard for the first time.

Speaker No, I don’t. I don’t remember the first time I heard Rachel’s dream, but I do know that there was always sort of a part of my identity that he’d written that song. And I do remember that as far as I know, that song had its origin. And my father and Mel Powell playing around one day with the song Three Little Words. And so they they kept the harmony and they switched the melody and it turned out three little words sort of inside out and backwards. That’s what Rachel’s dream became. And then I don’t know if that was the first one of their kind.

Speaker My father did for his daughters. But he did one for my sister, Benjy Benjy’s bubble. And for our three older sisters, Julie and Shirley steps out and high is fine. And when it was sort of a wonderful thing that he did that for all of us.

Speaker On.

Speaker You, one of the most marvelous things that you’ve described more clearly than almost anyone is this wonderful musician is your father was. He really had a hard time. And as a band leader as he was, he had a hard time talking about what you want to do differently. And you expressed this or experienced this yourself and you were able to describe sort of what that is like.

Speaker Well.

Speaker OK, here’s the picture of my father trying to convey what he wanted. We’d be out in a studio in Connecticut, this is where I can see it very clearly, and I’d be sitting at the piano and maybe he’d walk in and he just sort of. Start listening to me. Move over a little closer to the piano, he’d say, hey, Rich, you know what you’re doing there?

Speaker What what what do you try to do? A little different. And I’d say, well, what part you mean when you say what? I don’t know, he’d look at me, look at the notes and you say, well, like that put there. What did you try to do? A little different. And so, OK, we would have located the measure that he wanted different would say, well, OK, how do you want a different. And I’d say, well. I don’t know.

Speaker What do you just do it a little different? So then this incredible game and ritual began with my desperate search to play it not only differently, but better A and B, the way he wanted it. But he never, ever could convey what he wanted. So there was this kind of dance between us. Of me doing something, anything. Well, OK. Which meant horrible. Doesn’t make it at all. And we would go on like this. And then as things got more intense and he was getting more desperate and I was too he’d. He tried kind of poking out the notes on the piano with his fingers, which didn’t help at all. And then even worse, he tried whistling it, which didn’t help at all because he didn’t whistle. He couldn’t whistle. Or he try humming it, which was terrible because he couldn’t sing. But then maybe I mean, it didn’t always happen. Sometimes I would begin to get it and he’d say, OK, now you got it.

Speaker Then practicing was sort of an omnipresent thing in your life. And I guess particularly the kind of practicing where you would be looking for a good read.

Speaker Well, there you go. Well, I guess looking for a read in some way almost wasn’t practicing.

Speaker And see how I put it. It was it was a ritual that was part of practicing. So on the what. OK. And begin again.

Speaker Again. And we can forget about the practice. But.

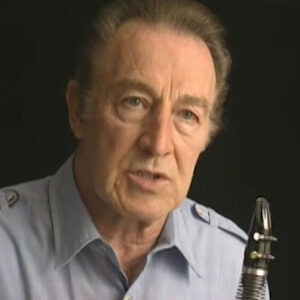

Speaker OK, what do you. Would you care. Which I do first. OK. Practicing. He sort of was always practicing. Before we had the studio, which had been the former garage, he practice up in his bedroom. And he just sort of be in there. I don’t know, three or four hours a day. And he’d learn new pieces or he’d go overall pieces like for Mozart or the vapor or whatever. And something I remember really well with his practicing was the kind of time he put into it when he was learning the Carl Nielsen Clarinet Concerto, which is an incredibly difficult piece.

Speaker And he just played it for hours and hours and hours and went over it. And it always used to just amaze me when people would say, your father still practices and what NAFTA, I mean, to think that anybody could achieve a certain level of expertise and that would stay there by itself. I mean, nothing ever stays there by itself. And anybody like him knew that extremely well. So he was always he was always pushing himself to learn new pieces and to keep practicing.

Speaker So there was one dimension of the practicing was just four hours. The discipline of going over the stuff of keeping it there. And another dimension. Of his practicing was the Reid qu’est? And. Days, that’s what he did, he’d sit out there, he had this little kind of periwinkle blue purple boxes, but two by three, I can’t think of the name Will. All of them were French and these reeds would be all over the floor.

Speaker There’d be like a burial ground of reeds on the floor.

Speaker There’d be 50, 60, 70, 100 reeds from one horrible day when he couldn’t get any read to sound. Right. And one of the things that always amazed me, because for as naive as I was in many ways about my father for many years, I did know this. He couldn’t tell when the reed sounded good. He could, but he couldn’t stop trying the reeds. He would become totally compulsive. And he’d.

Speaker Take out read after reading, you throw them on the floor, and then sometimes he pick up, read. They had already tried and case maybe they’ve gotten better on the floor. And he’d hold it up and he’d squint and he’d look at it and he’d put it in. And sometimes he would play two or three notes. I mean, those with a really bad times when he’d play two or three notes. Well, there’s no way. I think I don’t play a clarinet. You can tell him two or three notes whether a reed is is clarinet worthy. So there was this kind of compulsive, frantic quality that often went with the Reed Hundt to a closet.

Speaker And this is what you just tell story again next to your face.

Speaker Okay. It’s okay. It’s different. Okay. You would take the box of reasonable looking. Okay. Okay. Just tell me exactly the same story.

Speaker OK. OK. So he’d sit down to.

Speaker He had a straight back chair. And he sit down and have you have a bunch of reeds around him. So these there were these little boxes. They were about to buy three beautiful purple blue color with with gold edge.

Speaker They were great and. He take the Reids out. And he put them in the clarinet.

Speaker And he throw them out. He take them out of the kirtley, throw them on the floor. And he kept throwing them on the floor. And pretty soon there was his burial ground of reeds scattered all around him on the floor. And sometimes he’d pick one up because maybe it was going to sound different after five minutes on the floor. I don’t know. And it became a compulsive kind of search for him.

Speaker And you told us told you that last night it gets about. Sometimes when he was playing, he’s looking for the reeds. You do a specific exercise.

Speaker You like play the range, the clarinet and doodle in and out of jazz. He has to tell it without hearing him. You know, like you, you’d be downstairs. We’re right. You’d be right. Describe the scene.

Speaker Maybe the most characteristic. Pervasive. Sound I associate with growing up around. My father was the.

Speaker This little read ritual he had for trying out the read. And it would always be something that wherein he would go from the top of the register of the clarinet to the bottom of the register so he could get the full scale and.

Speaker Every single time it would vary because it would always be like musical free association, whatever tunes were in his mind were on his mind, would get smooshed in with the Reed tryout or the warm up because the warm up was sort of the retry out. And so he’d have little teeny bits, little measures or notes of classical phrases in there, and he’d have jazz phrases in there. And I mean, I guess that if anything really, you know, like those Hirschfeld the Hirschfeld cartoon, which just is my father musically, those retrials were my father’s juices. A fantastic cartoon is because it had all the elements of the classical and the jazz.

Speaker Which made up the kind of sound he was able to produce. So.

Speaker You know, I just thought of something that might be.

Speaker I think my father was really keenly aware of how. Much his classical training influenced his playing. I mean, at one level, it was something that he could fall back on at times in his career. When, let’s say he felt particularly insecure out of it or fearful that the jazz wasn’t going to maintain him as it always had. So that was one part. But the other part and he used to talk about this with me. I mean, he talks a little about music in any way. But I know that this was the case because he said frequently that in jazz. I mean, it is sort of funny from somebody who had as much technique as he did in jazz.

Speaker How can I put it? Didn’t matter how much he could or couldn’t do because whatever he could do was enough. But technically. But with classical music. He had to be at the level of that piece. The classical music, he felt always made a far greater demand on him from classic than jazz. And I mean, I think that’s really amazing.

Speaker Did he ever tell you about studying as a kid with the guys in from Chicago Symphony?

Speaker I don’t remember that story, but are those stories. But what I do remember is. Somebody writing me a letter when I was doing this search to find out information about him, that. This man grew up in the same neighborhood as my father. And all day after school, all my father did was practice clarinet when he was starting to play like 19 years old. That’s what he did. Two, three, four hours a day. That’s how he got good and. You can imagine it must have meant a whole lot to him to get good, to be willing to make that kind of sacrifice. Most 19 year old kids don’t me that point. It wasn’t a question of supporting his family. His father was alive. His father was earning money. But he worked so hard and achieved so much that by the time his father died, when my father was 13, he was able to earn a lot of money for his family.

Speaker There are other stories that you remember from his childhood. You remember telling that you’re that there were all these brothers and sisters, eleven in the family. Sometimes he would share the bed.

Speaker My father alluded to his childhood very, very little. He was not either an introspective or retrospective man, wasn’t his style. But I do remember. A couple of things in particular.

Speaker One is mentioning maybe just once that with these 11 brothers and sisters, I don’t know how many beds there were in the house in this basement, apart apartment in this basement apartment. But there’d be a whole bunch of them in the bed and they’d fit in. However they could. And then the one thing I remember him saying the most, maybe vehemently about the poverty of his childhood as we were driving into Manhattan from Stanford and as we were going after the Triborough Bridge, I was looking at some of these terrible slums and I said to him, can you imagine living in those apartments without air conditioning?

Speaker And he looked at me and he was really angry. He’s pretty. I mean, without air conditioning, without air and. I think I don’t know, maybe it was at that moment, it really struck him how different a childhood he was providing for his children, though, than what he’d had. I just remember that moment. It was very intense.

Speaker You’re your mother’s. Charles, we have been very different.

Speaker So tell me what you want about anything that she told you about her child or about your awareness that they sort of had had these different.

Speaker However you want. Yeah. It’s a very awkward church.

Speaker Well, one of the one of the really great mysteries of all time is how people from such. Not only of such different temperaments, because it happens fairly often in a marriage, but how people of such totally different backgrounds could have hooked up.

Speaker And my mother with her Vanderbilt heritage. Remembering. Dinner parties.

Speaker At which there were, I don’t know, 50 people at a table big enough to hold 50 people with not only a footmen behind every single guest, but instead of silverware, gold where on the table. And this is what she came from. And then through these basement apartments of my father’s were all the kids were smashed in to a few beds together, whatever way they could. I mean, I know he told me a couple times that he remembers there were times in his childhood when there wasn’t any food. I think it wasn’t often, but it was sometimes. And. There was this extraordinary difference in the kind of money and culture and lack of culture they had. And one of the ways that I used to see it come out the most often and to me the most amusingly, because it was so much aggression of the great and impossible divide was my parents different senses about the role of food in life. My mother was completely disinterested in food. She felt that her mother thought that food grew in the refrigerator, that her mother had no sense that somebody grew the food. Somebody had to choose what to eat, go out and buy it, prepare it, get it to the table.

Speaker I mean, it just sort of appeared because her mother and I think my mother, when she was a kid, never saw any of those things happen. It just arrived at the table and. My mother didn’t really like being. I mean, her idea of food was an egg salad sandwich for lunch and cornflakes for dinner when she was on her own, whereas my father had this Jewish thing for food and corned beef and the food, the food, the girls together. You don’t drink milk with a corned beef sandwich. You have cream soda.

Speaker And we would have these wonderful lunches at our house when I was growing up in Stamford. When particularly very often my father’s sister, Ethel, would come out from New York and she would come laden with beautiful cuts of meat.

Speaker There was this thing called Silvertip Roast that she used to bring in and boxes of pastries from Internments Bakery, and they’d sit around in our pantry and in this opulence of food. My mother didn’t order food like this. She didn’t know about it. She didn’t care about it.

Speaker Stuff, stuff so well.

Speaker This kind of attraction that my parents had towards each other in this really fascinating question of what were all these complex elements that that drew one to the other? One of the ways I would describe my father is that he doesn’t fit in the category of self-made man because that doesn’t say enough about how much energy he put into being and becoming who he was. My father was a self created man, which is a whole step beyond self-made. He had a vision in his mind that I think somehow he was somehow born with from a pretty early age and became aware of. And.

Speaker He grew into that slowly and he somehow, because he had this clarity of vision. Non-verbal clarity of vision he brought into his life. The things which he needed to achieve this incredible single mindedness of purpose that he had for himself. So when I look at like some old home movie footage of him on the beach in Venice, California, when he was 18, I mean, I see a young man who already had so much style. I don’t know, with its style came from. I mean, that’s always a very mysterious question about people. I don’t think it came right out of his family, out of that that immigrant background. But he had it. I mean, I think some people, they can just they can look at something and say, that’s what I want. I’m going to go get it. And one of the people that my father saw, whom he wanted and when it got was my mother, because she, too, had this enormous elegance of style. But the difference was that my mother was born into a background of enormous not only wealth, but culture. And so. She represented a world to him that he was moving towards. And I would never, ever say that my father was drawn to my mother just for the background that she represented. On the other hand, I would never, never say that he was oblivious. I mean, how crazy how could he have been oblivious to that? She was she was a lovely woman of enormous articulateness, which was a big balance to him because he wasn’t articulate and she had certain kind of social ease and grace that came from her upbringing. My father didn’t have that from his upbringing. He had to learn how to do that. And I think he watched and he studied and he assimilated it. But she represented all of that to him. And so in some way. And this is putting it more closely than I want, but I don’t know how else to put it. It’s as though she was in part a kind of ticket for him. Wasn’t that he didn’t love her, he loved her a lot, but she represented a world that he wanted access to. And one of the one of the amazing things about him was that he had this sense of elegance, which. Even despite his ugliest moments which were there, that elegance permeated so much of what he did. And I think it’s in the same way on the flip side. My my mother was drawn to my father’s kind of elegance. And we certainly know from Uncle John Hammond that there was a renegade spirit. And I think that was one of the things that joined my mother, Alice, and her brother John’s.

Speaker Right. Well, I’m not going to do it the way the rest of you guys are doing it. I’m doing it my own way. And so one of the ways she expressed her renegade spirit was in marrying this Jewish bandleader, which I don’t know. I think for her, in a way, mirrors the kind of step up that my father was taking with her.

Speaker For her, it was a kind of step up, not down. I don’t know how to explain it. That. That’s fantastic.

Speaker Growing up, my father was an extremely self absorbed man. And. The self-absorption was maybe one of his most positive and one of his most negative characteristics because of self-absorption and the focus in the intensity of get attention on what he wanted. Enabled him to go where he needed to go. Rosa drove everybody else crazy because it shut the rest of the world out. So one of the ways I might describe him was that he was always watching his own movie and who was listening, of course, to his own score inside his head.

Speaker And that was one of the most. That was one of the most salient aspects in growing up with him. I mean, on the one hand, I can talk about, well, yeah, I used to hear him practice X hours a day, maybe even more memorable for me. It was growing up with a father who sort of wasn’t there because he was always listening. He was listening to and watching his own movie.

Speaker He was always focusing on or he just go into space, begin whistling. He’d be gone. He wasn’t on the same planet with the rest of us.

Speaker And it’s like you want to go like there. Come on back, Benny. And sometimes he would and sometimes he wouldn’t. And I think it’s this self preoccupation and the inner movie that had something to do with a lot to do with this infamous ray that he put on people.

Speaker The ray was in part.

Speaker Looking through you. Kind of just stare because you whoever was wasn’t there because he was thinking about what was going on here. But there was also this other side of the ray that had to do with my father’s arrogant, imperious nature, which was very much part of who he was. So the other part of the ray was more like, go out and wash my car. I mean, it was very it was very nervous making because.

Speaker He made you feel like you were his servant often, and it’s his complex thing because on the one hand, it’s so demeaning, that kind of an attitude. But on the other hand, he could be demeaning. But he wasn’t only that. There was this. He shut people up when he didn’t need them.

Speaker And I think few of us have that ability. And it’s my sense from looking at whatever work I’ve done and in looking at the most creative people that I know, you have to be able to shut the world out when you don’t want the world around. And so that’s what he did. Another dimension of the way that I felt a lot was how can I put it? One one one aspect of the. Was getting it from the front, another one. He could shoot the ray from behind. And I remember when I be there’s his photograph. I don’t know, I was 13 and I was practicing and I wouldn’t be this young, naive little girl working at the piano. And he’s standing behind me. He’s looking at me just like so bored and so irritated and so she can’t fight this dummy daughter of mine.

Speaker And I felt that all the time.

Speaker And for as much as I suffered from that, why can’t you get it right, this dummy daughter of mine? I know now that he always said that about himself. He always said to himself, why can’t I get it right? Dummy, that I am. Because a lot of his career, he felt that he wasn’t getting it right. And that’s what kept pushing him and made him push the musicians because he always felt that it just wasn’t good enough. Plastic.

Speaker Another thing that he did that drove you crazy was he would insist that it was easy.

Speaker He was so.

Speaker My father was so unaware of other people’s feelings. A lot of the time, not all the time, but a lot of time. And. Because.

Speaker As is the case with all great musicians, because he mastered his instrument by the time he was 13 or whatever. I mean, did he when he was 40, 50, 60, 70? Did he remember what it was like to have to totally get that clarinet within his fingers? No, he had no recollection of that.

Speaker So when I was struggling to learn the piano and many kinds of things that I was trying to do, either musically or technically in the course of two very different things, musically and technically, he’d say to me all the time.

Speaker This is easy. What’s the problem? This is easy. And I wanted to kill him because it wasn’t easy at all.

Speaker And I’ll bet you a million dollars that he did the same thing with the guys in the band that either he said or he projected. And of course, actions speak louder than words or attitude, speak louder than words. He projec this is easy. Why can’t you get it? And it was so frustrating. And then it was doubly frustrating because not only did he think he was sort of a jerk because you thought it was hard, but he couldn’t convey how to. A narrow the problem, focus on and analyze it, and then, of course, he can never tell you how to solve the problem.

Speaker Fantastic. An example of that. Think of him being so hard on himself as you described the concert, he played Central Park.

Speaker He said he was never made it like he never really was.

Speaker I’m looking for a good topic. You find out. Yeah, I know. I know.

Speaker My father drove himself relentlessly, relentlessly.

Speaker And one of the things that always used to mystify me. Was there? I usually had the sense that not only was his own worst critic, as, of course any great artist has to be, but he was also his own worst judge.

Speaker He didn’t know when he played well and he didn’t know when he played badly. Ed McMahon. I grew up around music. I know music really well.

Speaker I had some sense of when he played well and when he played badly. So I certainly was more objective much of the time than he was. But I remember one evening he played in Central Park to an audience of I don’t know how many thousands of people. And this was a night when my sister Benji and I were staying in the apartment on 66 Street.

Speaker We were all in there because of this concert he done. And he came back from his concert. I don’t know, midnight.

Speaker He tried to read for two hours after the concert, and it was like self flagellation, it was like these these pictures that you see in Italy of the months with these things just beating themselves, that’s what he was doing to himself because he obviously thought he had played just horribly. And. And one of the things that was also very frustrating about being around him, he didn’t care what other people thought.

Speaker He just couldn’t have cared less. Too bad. Whatever anybody else thought, he knew what was true. So if he thought he did a bad job, he did a bad job and nobody was going to convince him otherwise.

Speaker It wasn’t quite clear. Just take this shot that he came back in the in the door, the apartment upstairs. And you heard these sounds. No, no, no. I was OK. OK. We’re talking about just returning from the concert. OK.

Speaker At midnight when.

Speaker So after we came back from this concert at Central Park.

Speaker My sister and I went to bed. But our father.

Speaker Began trying out raids. And he stayed there in the living room, trying out reeds for two hours after accountably play to. I don’t know how many thousands of people. And it was like it was like watching him flagellate himself. This kind of self-hate score.

Speaker And in the end, the adulation he’d got, he he’d received that evening. The fact that so much of his life he’d walk in the room, in the room would go crazy with adulation in some way. It didn’t mean anything to him. And I think that’s part of the secret of success for a lot of great artists. It really doesn’t mean anything to them because they’re always pushing themselves to create that sound. Not not even as well as they did it yesterday better than they did it yesterday.

Speaker What was it like being around that horrible all the adulation?

Speaker Well, when you talk about the lightning round, the actually. Oh, God.

Speaker Oh, yeah.

Speaker You’re getting warm. No, no, no, don’t, fine. Not at all, not loving love to talk on the adulation being around.

Speaker The level of education that my father received from my whole life was was one of the most complex dimensions of being his daughter, because I guess the three major ingredients. One was the constant or that I felt. Towards feeling, towards watching somebody.

Speaker Who would bring up a roomful of people to their feet screaming and clapping within the moment he walked in? So that was the all part. Then there was the N.V. part. I mean, I’m a human being. I wanted that, too.

Speaker I don’t know if maybe other offspring of famous people don’t feel that I want to be that great, too.

Speaker But I felt a lot of that and.

Speaker Then another aspect of it. So let’s call it really negative, the envy part. But then it was positive. That’s my dad. And I was really proud of him. So there were all these.

Speaker It’s like, I don’t know.

Speaker It’s like a cord with a C and an E flat and a G. It was a minor chord. Like in here, these these these nice harmonic notes here. But there’s this bass minor in the middle. And that’s the way I always felt watching the adulation that he always had.

Speaker And I mean, you spoke earlier before, it’s very wrong about being the child of a famous person, something that the society does to live with that fame. And that’s a hard thing to go with. I can always hear what the phrase you used was, OK.

Speaker I don’t know. I don’t know if you want to use this, but I’ll give an anecdote.

Speaker It was. Wonderful and horrible being offspring of somebody as famous as my father. It was extremely difficult for me. I mean, I don’t think in some sense I began to know who I was until he died in some kind of sense. He was such a presence. I mean, he still is, even though he’s been dead for seven years and people who were that big and who feel the world’s imagination as much as he did are pretty oppressive for those around them.

Speaker I lost my father, who was not a good record. OK. You said.

Speaker Let me come back to it. I’m just I’m blanking out right now. We could just come back to it. Let’s something else out.

Speaker Can you shift your bodies like this? OK. Tell me what you want. More towards orange. All right. Let’s talk about Uncle John. Hmm. And you know the difference towards blacks. Yeah. OK. OK.

Speaker OK. OK. Yeah. OK. One of the most.

Speaker Interesting contrast that one could ever see in the attitudes of two men towards the same phenomenon was in the difference between my Uncle John’s attitudes towards black music, attitude towards black music, and my father’s attitude towards black music. My father was I mean, he was interested in politics. He was well-informed man. But in some very profound sense, my father was really apolitical. He had music to play. I mean, he couldn’t.

Speaker He was very practical. He couldn’t say he never he never gave energy to what wasn’t going to help his music.

Speaker That was the bottom line for him. So when he hired black musicians.

Speaker I mean, I would never say that. I don’t know, I think the term colorblind is always sort of naive. I mean, obviously everybody notices color, but.

Speaker It really, truly didn’t make any difference. My father, I know, never hired Terry and Lionel because he had any cause or mission to fulfill other than his music. He heard these two incredible guys and they had a kind of sound that totally meshed with what he wanted. They created a new kind of music together. So that was the reason that he hired them. And then he hired them. All the other black musicians. He did. Now, as to his.

Speaker The risk he took, the statement he made in doing that at that point in American history.

Speaker He didn’t give a damn. People didn’t like it tough. That was the way he felt about everything. You didn’t like it, too, but he was going to do it anyway.

Speaker I mean, he had a rhinoceros skin enviably. So unless, of course, it happened to get in your way, then it was a problem. But he did what he wanted to do because he believed in it. Whereas my Uncle John.

Speaker Loved this music.

Speaker But it was really different for him because on the one hand, with my Uncle John from his Vanderbilt background, it represented this renegade side of him. So it was a way to to defy convention and what he was supposed to do as the son and that kind of a background. So that was one dimension for Uncle John. Certainly wasn’t there for my father. Another thing for Uncle John was he was deeply, passionately committed to the cause of promoting black music and to helping black musicians.

Speaker Now, Uncle John, of course, wasn’t a musician.

Speaker So it was a completely different attitude towards the subject. And yet somehow.

Speaker They both were two of the white men in America who did the most for black musicians, but simply completely different points of view.

Speaker Did you get a sense of the tension in their relationship, how much you won, because it is your family there, different sides of the family? But I will say touching on it in some way. Is there anything?

Speaker Let’s see how censored can I. I mean, when I was it was really bad, but I don’t think I wouldn’t feel comfortable. I don’t know how I could talk about it without it being too much.

Speaker Boo boo, boo boo boo.

Speaker There were a couple of songs were touching on the Vanderbilt Vanderbilt’s. Tell just too much.

Speaker Well, there’s one thing that I think I would feel comfortable saying, and that is that I would say that one reader.

Speaker Oh, yes.

Speaker Looking back on the very intense relationship between my father and my Uncle John. I can think of one thing which had to be one aspect of the relationship which had to prevent. Can get. Looking back on the relationship, the very intense relationship between my father and my Uncle John. I can think of one dimension which had to be very problematic for them.

Speaker And that is he was my father, this self created man who had.

Speaker Gotten where he wanted to go on his own.

Speaker And who was intensely proud of that, although he never would’ve said that. But I mean, I’m sure he was. He was my Uncle John whose life was finding musicians. Now, Uncle John wasn’t a musician. I don’t know how much he wished he had in one day, but he wasn’t when he found them. He helped them. With their careers an incredibly powerful way, and I think that my Uncle John often took some credit for helping my father with his career. My father didn’t want anybody taking any credit for helping him with his career. And I think that that one factor presented a kind of conflict between them that was always sort of there.

Speaker We get to this playing a little bit in their world. If you don’t mind, just starting to get from the obvious, I’m, you know, took some credit for it. OK. Not not not the intro. You wouldn’t happen again.

Speaker OK. Uncle John took some credit. Okay.

Speaker Or you can start one step. OK? His job is discovering musician.

Speaker So on the one hand, he was my father. Who is a self created man? Who? Always made it his business to do everything for himself. Two to two follow this incredibly focused goal he had in his life, whereas.

Speaker Here is my uncle John, who discovered musicians who, by definition in his life, in his in his job, put musicians in a place of visibility and help promote them. So, of course, what Uncle John did, he took credit for helping musicians with their work. And I know that he did that to some degree with my father.

Speaker My father didn’t like anybody taking credit for any part of his career because, I mean, this is kind of Jewish ethic of you do it on your own. Nobody’s going to help. And so he was this this irresolvable conflict between the two men that the one person who was born with everything and who wasn’t a musician, who was going to take some credit for the the career of a man who never wanted anybody to take credit for anything that he did.

Speaker It was interesting. Someone came over. There was a relative or a sort of poster of the family mentioned to me that your grandparents, I guess, on your mother’s side, had, as some have expressed, benison concern about for John. You can’t really get it together in his career. You know, here is this incredible figure in American music that because he sort of was, in a sense an amateur, even get paid for it. Well, that’s a valuable guilt, too. Yeah. I mean, you never were aware of that sort of that he, you know, maybe felt that, you know, that he wasn’t as good as your father because he had a career he didn’t have, you know?

Speaker Oh, I’m sure he did feel that. You want me to say something about that?

Speaker If it’s appropriate. If there’s anything specific.

Speaker Let me just think for a moment about that.

Speaker You have to set the scene for me to say, of course, that my Uncle Fred Fielding was OK.

Speaker Just like two or three sentences later. OK.

Speaker We were in Mexico having dinner with my Vanderbilt side cousin, Freddie Field, his lovely Mexican wife. And during dinner I remember really well him turning to my father and saying with true amazement and envy, said, Benny, you’ve got a better Harvard accent than any of us.

Speaker Describe this. But when you went to rehearsal. Your father’s band, you hadn’t been often, if ever you saw the score and yes, it wasn’t.

Speaker The.

Speaker Great eye opening moment in my understanding of what swing and jazz are came one day. I was growing up. I don’t know, 30. And I’ve been at a rehearsal in New York in. I tended not to do that when I was a kid. He just didn’t have us around for his rehearsals. So the musicians have packed up and gone home and my father was undoing his clarinet and putting it away. I was kind of walking around.

Speaker And I stopped and I looked at the score. Let’s say it was one o’clock sharp and I looked at the score. And here were these quarter notes and whole notes.

Speaker And I look at my father and I said, I mean, like this alarm because my world was kind of crumbling around me. I said, why does this music look like that? I don’t understand it. Why does this music not look like jazz and history? I don’t know, cleaning out his clarinet and putting it away.

Speaker What are you talking about? What does the music look like? What did you think it looked like?

Speaker Well, I always thought that jazz music had 30 second notes and 60 fourth notes along. I don’t know, one hundred and twenty, whatever notes. So that you could get all that 20, is it?

Speaker Well, what do you. You can’t put swing in music. You can’t write swinging music. You just play the swing.

Speaker And I had never realized that.

Speaker And I figured that if I had age 30, a trained musician, Benny Goodman daughter, didn’t know until that point in my life that swing cannot be written then a lot of people who probably love swing don’t realize that swing is one hundred percent what a musician does with the notes.

Speaker No, last thing I have is your. Describe to me that he went through this constant conflict about whether or not to modify or modify style, that it was never enough what he’d done. And so he kept going into to change after.

Speaker Put on the funny phrase that remind me when there was something that I wanted to get back to. But what was that? That I didn’t finish.

Speaker I blocked about the about being a child of.

Speaker A famous person.

Speaker One of the aspects of my father that I think best characterizes this incredible double edged sword of his personality, the very positive and the very negative was in his.

Speaker Unwillingness to change his style. Now, on the one hand, it’s very easy to describe their unwillingness as sheer arrogance. Look, this is a kind of music I play. You don’t like it. You don’t have to buy my records. I’m going to play what I want to play. And. At the same time, there was this purity of motive that he had, he had a sound. He put it on the map. He was that sound. He was identified with it. It was his life and his everything to him. So. In some sense, it’s so admirable that he refused to change that he had his little forays in the 50s. He had a little forays trying to get into pop. He considered, well, should I jump on the bandwagon? Should I go with where the world is going?

Speaker And then he said, no, I’m not going to do there because I play what I play. And one of the things that I find so amazing about him is that he managed to maintain that style, which really was a complete anachronism by the time he died swing. I mean, some people were listening to it, but it was hardly what you call popular music, was it anymore. But he continued to play it because that’s what he believed in hopes.

Speaker So that’s the.