Speaker Prescott. OK, just slide it.

Speaker This is, uh, April twenty ninth, and this is the first tape of our interview with Raymond Fielding for the Henry Luce project, American Masters.

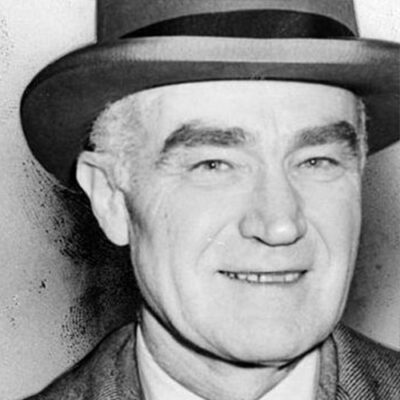

Speaker So we’re doing a. Ninety minutes on Henry Luce, who.

Speaker If you’re under 40, may not know who he is, which is something I was really shocked me when I started doing this project because I doing this thing of Henry Luce.

Speaker Education, even though I didn’t know he was. So what do you think would be?

Speaker The most important thing for us to release was a powerhouse.

Speaker He was a man of great will and a great deal of imagination who was partnered with some other people of great imagination, too.

Speaker In the early 1920s, he and another Yale graduate, Briton Hadden, created Time magazine. And they also acquired at the same time a man named Roy Larson, who went his own way, had wonderful contributions to make to the company. Lewis was the engine that made the whole thing run. He’d been born in China. He was a born abroad expatriate. He was American at heart. He had very strong opinions about everything, a little bit conservative and a real sense for print journalism and a desire to create a new kind of magazine, something that hadn’t been done before. Something that broke all of the the conventional ways of putting a magazine together, creating a magazine that really hadn’t existed before, which took other people’s news from other other sources, put it together, rewrote it, cast it into a new kind of language, which some people called time speak in which he took he and his people took the the English language and refashioned it and made something very vivacious out of it. It’s exciting and began to include photographs to photographs that were integrated organically into the text. It was a magazine which annoyed everybody. It annoyed the elites because it appealed to the public, was very popular magazine. It annoyed grammarians because it took great liberties with the English language and it annoyed the competition because it lifted a lot of news stories off of other newspaper editions. But it was new. It was fresh. It. It was a fast freight on the high island of 1930s and 1920s journalism. And it startled a lot of the provincials along the way. But it made its mark not only on the public with what it had to say, but it made a big mark upon its competitors in magazine journalism.

Speaker What?

Speaker What importance do you think he had in the kind of cultural landscape of.

Speaker You know, America, during that 40 years that he was I think the magazine had enormous impact upon the public, the public. And we are all part of the public.

Speaker There are many publics, I suppose. But we are all we are all consumers of media and of the products that they dispense. And the styles with which the media have changed their dispensation have occurred with great rapidity since the coming of time. Time moves so fast. It had so much velocity. And of course, it was very timely. It focused its attention upon people that hadn’t been paid too much attention before. It emphasized the sciences, of course, politics, the growing threat of war in Europe. Everything was part of. Partly it was grist for their mill. And they just did it all better than anybody else at the time.

Speaker When you were younger. Where did you. Growing up was a time in life with a part of your house.

Speaker They were part of our household. And when I went to college at UCLA, I spent about two weeks in the main library in the stacks. And every night I went over and spent about two hours and sat down on the floor and went through the entire set of Life magazine. And it was the best, the best instruction I had in 20th century history. And of all the different threads of our lives and our traditions and our culture and how they came together and how how they went off in different directions.

Speaker Well, especially. Sort of left leaning people. Sort of have this love hate relationship with time and again talk about time in the Luce era.

Speaker If you run into that thing, you sort of describe what that time has a reputation for being, or at least in in past years and perhaps today, too, as a reputation for being for leaning a little bit to the right, being a little bit conservative and on some particular issues, especially in the early years, of course, Mr. Luce had very strong points of view, especially with regard to China and the loss of China, as they called it, after the Second World War.

Speaker As for the men and women who made the magazine, who wrote it, who edited it, I think that they were pretty middle of the road or even fairly liberal people. But Mr. Mr. Luce brought a somewhat conservative point of view to it. This made some of the other publications that came out with its name ironic in character, especially the March of Time, which was a predominantly liberal publication on motion picture film.

Speaker Of course, one of the great ironies was the publication of Fortune magazine in 19, what the early 1930s actually came out 1929 and enjoyed a considerable success at a time when this country plunged into one of the great depressions in economic history, elegantly printed and of course, celebrating capitalism, which I suppose is the way to look at Henry Luce. He celebrated capitalism, free enterprise and the opportunity that he felt America meant for and provided for the average person.

Speaker Let’s let’s talk about March. How did the march of time come to be march of time?

Speaker Was the creation of Roy Larson, who was a vice president of time. They’d been brought in at the very beginning. A fellow Yale graduate. Brilliant man. Very cool, very a good business man, but also with a quite experimental and creative point of view. He’s what Marshall McLuhan used to call an electric man, very much plugged into every new medium that were that had appeared and were beginning to appear. The new media with which we live today very receptive to everything new. And from the founding of Time magazine, of which he was a circulation director in which he whose circulation he built with great skill and profit, he began to experiment with other media during the 20. Time magazine ran some other publications, this time with radio, and they had one called pop quizzes little 15 minute thing which dealt with news events of the day, which will publicity for the market for or for Time, Inc.. They had one called Newscaster’s, which was very interesting because they began to recreate the news if they didn’t have the real person to speak on radio. They’d find an actor to simulate the voice. And finally, in 1931, they introduced the March of Time half hour television show, sometimes on CBS, sometimes NBC, and with different sponsors over the You said television show.

Speaker Oh, I’m sorry. Right now all are. Yes. Yes. Right.

Speaker We can pick it up again from the top from the development of.

Speaker Right. Beginning in the late 20s, Larison decided to use radio, which was an increasingly popular medium of communication, to advertise for the march of time. He had two little 15 minute series that were fairly successful, didn’t make any money, costs, cost the money, but they appeal to audiences. And one was a kind of a pop quiz show about news events of the day. And the other was called newscasting. And it began the process of recreation or staging of re-created news using actors. It was an interesting experiment. And in 1931, they introduced a half hour radio march of time, a play on words and a fateful one and a very popular one. The show was immensely successful year after year. The polls ranked it one of the most popular shows on radio. It was a news show, but it was also a dramatic show because nearly all the voices on the show were performed by New York actors, some of whom in time became quite well-known. Orson Welles was one. Everett Sloane, very distinguished performer Ted de Corsia played the voice of a much Fellini. Agnes Moorehead played Eleanor Roosevelt. Dwight Wiess played the voice of Hitler. And very well indeed, Art Carney played a wonderful Franklin Roosevelt until the White House complained after a period of time and said, you’ve got to stop this because people think that Mr. Roosevelt and he’s saying things he didn’t actually say. The show treated current events but dramatized them and with a powerful narrator who at different times were Harry Vonzell. And then later Westbrook Van Warty, known officially as the voice of Time, known unofficially as The Voice of Doom. Mr Van Vau, he had one of the great voices in Radio A, he would say, What does it portend? What does it mean for Americans? America looks west to Japan rearming, invading Manchuria. No man can tell. Time marches on. It was wonderful. It was wonderful. And the show was a great success and went on for many, many years. Different sponsors well into the 40s. Occasionally they lost a sponsor because it was a controversial show at which anti Nazi it was antifascist, also anti-communist, and made no bones about saying so. Finally, in the mid 1930s, having made a substantial success out of the radio show, Roy lost and aspired to create a motion picture version of it. But he didn’t know how to do it. And he, as he said to me, said a lot of wildcatters came Gambi with different ideas, but none of them worked. And finally he said, I found the man who could do it. It was a man named Louis de Rosemont who was a veteran newsreel man who’d been with Fox Movietone News for many years and who was anxious just as Larssen was to get behind the news. The newsreels, said, Grossmont, are stuck in the mud. He said, they’re superficial. They’re witless, he said. What does it all mean? How can we how can we get behind the news? And he said, I’ve got a way to do it. And so indeed he did. So I took all of the actors, plus many others from the New York stage and New York radio scene, including many that looked like famous people, someone who they would lay a light in deep shadow who looked a lot like Adolf Hitler. Another who looked like Mussolini. True heel. They had a pretty good double for him. They’re a whole show on the Dominican Republic. Trujillo, whom they call the dictating US dictator that ever dictated this shows, were fun. They were they they punctured pomposity wherever they found they were. They were what we would call confrontational journalism. They took on a lot of powerful people, including what TIME magazine called the lunatic fringe, which were political extremists of the 1930s. And they exposed them. They were sued regularly. They never lost a case in court. They never dared again ever go into the state of Louisiana after they did an issue about Huey Long. They were afraid of nobody and and they simply delighted audiences. This was an enormously popular motion picture. It was released to more than 20 million people a month, once a month, plus many more abroad. And that’s a an audience that many a television producer would envy today. They dealt with every imaginable subject. They treated some subjects that no other Hollywood filmmakers dared touch. They were the first to deal with venereal disease and to use the word syphilis in a motion picture. They were the first to attack Nazi Germany and inside Nazi Germany. They won a full issue, a 20 minute issue in the late 1930s, a film that was probably more controversial than any motion picture that has ever run in a theater. When it opened in New York, the so-called alien squad made up half the audience that people would get into fistfights when they saw Adolf Hitler on the screen. We forget that in those days he was controversial. He’s not controversial today, remembered as one of the great monsters of history. But in those days, we had many good German Americans who hoped for a better time for the mother country. Let’s get the economy back on its road. Maybe this man Hitler can do it. And you had a lot of other people who were convinced Mr. Hitler was not the one to do it. And you’d have fistfights in the theaters. You’d have people rolling in the aisles when it dealt with the subject. One of the newsreel companies in time for a period refused to show the scene, AC in a shot of Hitler on their screens, on their newsreels, because they said, you know, they tear up the theater.

Speaker We’re not in that business. We’re in the entertainment business. March of Time said we’re in the idea of business. We’re in the idea, the business of controversy. And so it went from 1935, miraculously until 1951, 16 years it survived. The only film series in the history of the American Motion Picture two consistently and persistently treat controversial subject matter best.

Speaker But I will. Get more specific now.

Speaker How?

Speaker As the newsreel was march of time different from other.

Speaker The newsreel had been introduced in this country way, way back in the in the second decade of the century and lasted until about 1967. It was a popular and necessary part of every motion picture show. It preceded every feature film that ran in America. It lasted for more than half a century. It was part show business, part journalism, not very good journalism, rather superficial, sometimes witless, but sometimes it was wonderful, filled with vivid pictures and sounds of both the wonders and the horrors of the 20th century, which we all did our best to understand and confront. But it was not a journalistically sound piece of work. It was built like a newspaper. You began with the big events of the day. They got grow there as this nine or ten minute sequence would pass before your eyes. Everything grew a little less significant until you ended up with the newsreel equivalent of the funny papers. You ended up with Lou Layer on the monkeys. The march of time said this is all very well, but we want to do something a great deal different. We’re gonna have a 20 minute show. For one thing. And it is going to explore issues thoroughly. We will have talking heads. We will have. We will interrupt the shot. We will interrupt the flow of the film. And we’ll have text on the screen and the audience will read the text, as you do in a newspaper. And then we will pass on to the next subject. And Louis to Rosemont said, In those cases, which so often happen when the newsreel camera was not present, when an important event happened, then we will stage it and we will. And they had sets. They had full a crew. They had the actors. They had costumes.

Speaker And they would do a whole issue in which much of it would be staged with actors and it would be integrated with real newsreel footage from the Fox Movietone Library. The thing that made the March of time work was their access to the Fox Movietone Library. Louis went above his immediate superiors had and got the permission from Fox Movietone for them to buy as much footage as they needed. And the the integration of it was really quite skillful. In time they made feature films, one of which the ramparts we watched as one of the most skillful blending of re-created material and authentic material that’s ever been done. And it was a warning made in the early 1940s that we’re about to have another war. And it takes a look at the First World War. And it said, look what this man, Hitler, is doing abroad. They even stole footage from film Jungle in Pullum famous Nazi propaganda film and built it into the ending of the film. Very aggressive film, a very aggressive kind of production. In contrast to the newsreel which didn’t want to make any waves.

Speaker The position of the newsreel was an entertainment device. It was a part of the black book program. It was given away almost free of charge. And in those rare instances in which had accidentally captured some really controversial images, such as the Memorial Day massacre, so-called at Chicago Steel Strike, the newsreel itself suppressed the footage until the La Follette committee subpoenaed it and then released it. And even then, it never ran. In Chicago, police chief Elaman saw to that the march of time was censored all over the world. Even among allies and friends of ours in Great Britain, it had a French version. A British version had a Spanish version. Of course, it never appeared in Italy, never appeared in Nazi Germany or in Russia or in Japan.

Speaker You did it. Did it appeal to. American viewers in a way that other newsreels didn’t I mean, well, how did audiences react to this new 20 minute news?

Speaker The newsreel was all the conventional newsreel was was always popular and it was kind of fun and had a lot of showbiz stuff and a lot of silly stuff, too. Together with an occasional exciting scene of floods out in the Midwest or an earthquake in California or whatever, it was the news event of the day. The march of time when it came on, you knew something was happening. Had very powerful musical score by written by Arlen and the voice of Westbrooke van Rawhi. And he says, The march of time and pow, you’re off and running. And the audience knew it was going to be engaged and it was gonna be engaged in a fun kind of way because it was fast moving, very well edited. Louis Grossmont was a master editor. He knew how to put the thing together. You had famous people speaking and in time the march of time grew so popular.

Speaker Susan.

Speaker I don’t think it ever stops. I think it’s fine. OK. Gilliver here.

Speaker You what, you were just a brave God, right? Was the response of audiences to some larger.

Speaker Audiences were galvanized by the march of time and they were engaged because these these issues were dealing with controversial matter. But they did so in an exciting way and they did so oftentimes in a humorous way. There was much humor to the audience. Loved the march of time. It was extremely popular series.

Speaker And in time, it grew so popular that the real people began to perform and they were able to talk politicians. Douglas MacArthur and Einstein. And they did a wonderful issue immediately after the Second World War about atomic power. And they got all of the people who had played a role in the development of the atomic bomb to perform their roles. And they stayed.

Speaker They had sets that they built that looked as far as they could tell what the bunker looked like out at LMR, Gordo at Oppenheimer and Fair, me and Banaba, Bush, Einstein, who they photographed at his home in New Jersey to recreate the writing and the sending of the famous letter to Franklin Roosevelt, which inaugurated the atomic program. Some of these were kind of campy by today’s standards. Even when they were made, The New York Times used to refer to what they called times amateur theatricals. The important thing is that audiences of the day and myself, I was a child at the time and it all see were you know, the films have been there in the vault for all these many years. They haven’t changed. It’s audiences that change. And today we’re we’re much more sophisticated and we look for a little bit more polish in these things. But at the time, we thought it was quite fine. And you understand, the time did not tell you that they were faking the footage. For some people, it was obvious and for others it wasn’t. Today, at the bottom of the television screen, the ethical way in which to handle this is an announcement. This is a recreation. But in those days, I just presented it and and ran with it.

Speaker Was it was the. Was the idea of recreating the news this way, was it was that, uh, did that originate with the market?

Speaker This notion of of staging the news?

Speaker As a consistent and typical feature of the series originates with the march of time. Now, of course, the newsreels were not always that authentic themselves. There are a lot of fake newsreels, beginning with the Spanish and Spanish American war. Most were shot in New Jersey by the Edison company. So the idea of staging it was certainly not new. But to use it as a technique and to make no bones about it, it was well-known. They didn’t hide it. They didn’t publicize it. Louis de Grossmont had a point of view and with a lot of attitude, he said, look, in conventional newspaper publishing. He said the report goes out, gets the story, picks up the phone and calls the rewrite man. And the rewrite man sits there and he rewrites it. He casts it into a journalistic form for a column. Given the space that’s available and the importance of the story said, I have the same right to do the same thing. And he said frequently, as far as I’m concerned, my recreation a sharper it is more accurate, it is more telling than it would have been if a camera had been recording it at the time. If there had been cinema verité, as they call it, in the days of Louis de Rosemont solo show, Lothar Wolff said, then we would have shot cinema verité. He said we wouldn’t have had to restage you. But he said cameras in those days, a sound camera weighed about 80 pounds. He said, you had a sound truck. You didn’t have portable sound. You had optical sound. You had lights which were not very efficient. The films were very slow. And he said to set up and to recreate something like this was a semi theatrical enterprise. But he said if we’d had today’s technology, we would have gone with the so-called direct cinema or the cinema verité technique.

Speaker What? Did it adapt? Time storytelling techniques to.

Speaker The the language that was written for it pretty much mirrored the stylistic eccentricities of of Time magazine. It really was a kind of unauthorized English. There was a parody of it in The New Yorker magazine that Woolcott Gibbs wrote in which concluded, he said Backwood ran sentences still real. The mind where it ends knows only God. And it was fun. It was fun to listen to it. Word games are always fun it to challenge you in every way. And a very fine musical score that Jack Sheindlin scored every every issue had a new one. It was a meticulously edited by Louie and his people. They worked under great pressure. And fortunately for him, they worked without interference by Mr. Loose. According to Roy Larson, Henry Luce really never quite understood what the march of time was all about. In fact, when Larssen in the mid thirties proposed it as a substantial investment two hundred thousand dollars just for the experimental real’s, he was so enthusiastic, he said that Henry Luce said, I think you’re much too into this, too presented to the board. I will present it to the board. And so we did. And as with the radio series, it was a great deal of internal unhappiness for the proposal. They felt it cheapened the just said they did with the radio. They felt it cheapened the time slot, a logo and the time reputation. But of course, it didn’t. It enhanced it hugely. And Mr. Luce hardly ever came over to their production headquarters, which were in the 20th Century Fox building over in west New York. According to Richard Grossmont, who succeeded Louis as producer, about the only time Mr. Luce would interfere was when they did an issue on China, about which Mr. Luce had very strong opinions. And then he said, I would plan to take my vacation and head out of town for two or three weeks and let him have his way.

Speaker So he really was so loose, was really pretty hands off with regard to words.

Speaker Yes. Lucia was a traditional newspaper or print oriented person. He was not what McLuhan would have called an electric man and what he did. He did very well, of course. And he was personally a person of great will and power and many friends in high places. He was the masthead leader for the for the Enterprise Larssen. On the other hand, working with the march of time and radio and film was a much more inventive version, much more experimental and much more willing to to accept innovations in publishing and in communication.

Speaker So what’s so loose on the idea?

Speaker Larson sold the idea to lose solutes, took everything that Larson said very seriously, Larson was a very successful vice president and later, of course, he became general manager. He became publisher of Life magazine and finally became president of Time and Corporate. He was the only one who survived. The other two creators having passed away before you did. So his enthusiasm captured Luce’s imagination. And the only trick then was for Lewis to present it to the board of directors and convince them that this wasn’t some harebrained idea, but something worth exploring.

Speaker Let’s let’s go back to and talk a little bit more about specifically the.

Speaker OK.

Speaker The uproar over inside Nazi Germany, inside Nazi Germany was perhaps the most controversial film that ever ran in American theaters. We have to forget that. Let’s try it again. Inside Nazi Germany was perhaps the most controversial film that ever ran in American motion picture theaters. In those days, the subject that it treated, which was Nazi Germany and the rise of Nazi ism, the rise of fascism, the rise of Adolf Hitler were matters of controversy. There are many German Americans who thought to Hitler was a strong man, just like Mussolini. Mussolini made the trains run on time. As they said Hitler was not yet the monster. Horace not remembered as the monster. Word was just beginning to to emerge about the repression that was being brought upon his own people by him and about his designs and plans for expansion within Europe. The march of time sent Julian Bryan to Germany. Brian was an excellent documentarian, good filmmaker, good cameraman, and he shot a lot of footage in Nazi Germany. But he had his keepers. He had his monitors with him and his handlers, as it were. And they only allowed him to photograph certain kinds of things when the footage got back to the United States. Louis and Larson looked at it and it looked pro German. I mean, here were scenes of happy people on picnics and working so hard strength through joy and all that sort of thing. Not a hint of imprisonments. The concentration camps which were already at work. The anti Jewish programs. Nothing on film. So they staged scenes in New Jersey. They see a stage and a scene of nuns that had been imprisoned. They staged scenes of anti Jewish pro program detailed in the cities, the rounding up of citizens, the concentration camps. And they put a profoundly anti German narration on the film. What this produced was a film which unfortunately could be taken as either pro German or anti German. Jack Warner had a Warner Brothers was so upset by the film. He said the effect is pro German and it will not run in Warner Brothers theaters. Other theater owners, of course, we’re happy to run it because it was a big one. It was the first issue in which the March of Dimes and Time devoted the whole 20 minutes to one subject. And it was a it was a gasser. It. It got reviews and newspapers and magazines. Whatever the political point of view of people, they vented their wrath or their pleasure upon this particular issue. It ran for one month, as they all did. And most people in the film business were happy to see it go.

Speaker How do you spell that? It’s yours. Yes.

Speaker Yeah. Right. I’ve met him. Yes, yes. Yes.

Speaker Good man. Good man. And he’s written a great deal, I think, about. Nazi Germany. Germany. I think maybe for.

Speaker Also, Columbia is Columbia, South Carolina, where the university. They are going to be going off there in July for a conference. They own a good part of the Fox Movietone collection that were given to them.

Speaker Yes, right.

Speaker So let’s talk about ramparts we watched. It seemed to have been, you know, was feature length. What what what was the thinking that went into making ramparts? We watched. Where did it come from?

Speaker At Time, Inc., everyone from loose on Dunwood, but especially in the march of time, it was felt that a warning was important that a bell ought to be struck. The alarm bell about the rise of Nazi ism and fascism in Europe.

Speaker And that whether we liked it or not, whether we felt profoundly isolation, the stick, as many people did, we were going to end up in that war again.

Speaker And so they decided to tell the story of a fictitious but nonetheless typical German American family during the First World War. And what happened as we entered and went through that First World War experience, what happened to Americans when caught up in the emotions of the period, especially for four German Americans and how their position in the community changed and how they responded to it?

Speaker And then the period that followed it. Concluding with stolen footage from German propaganda films of the. The destruction of Poland, the war had already broken out beginning in September of 1939. And the film ends with a warning, America, look up and better build up that Navy again. And you might want to pay a little attention to the armed forces because we’re gonna be in this war once again, whether we want it or not. It was a very well-made, propagandistic piece of work, and it was an argument that America had its obligations. And it would be it would find itself having to shoulder those obligations, whether it wanted to or not.

Speaker So loose commission, this board commission is the March of Time Commission it itself.

Speaker By that time, Larssen supervised everything that happened at the March time they reported to Larson. And absent any complaints from loose and the board of directors, the march of time could do whatever it wanted so long as it pleased Roy Larson. So it was generally. There were several features that were made. One called We Are the Marines with a lot of fake footage shot off the coast of South Carolina of Marines practicing invasions and that sort of thing. As we look at a lot of footage from the Second World War, we have to try to figure out where it all came from because there’s a certain amount of faked footage there as well. The march of time was a very patriotic organization.

Speaker It was antifascists. It also anti-communist. It had a slightly liberal point of view. In my opinion, that’s a matter of perception, of course. Louis Grossmont himself was a man too difficult to plumb. On Monday, he was a little bit left on duty with a little bit right. He was very stormy personality, a genius, a kind of genius and a difficult man to work for.

Speaker So how did how did they release their policy watch, how did people come to see Rambo was released into motion picture theaters as a feature. It was censored in Pennsylvania, never ran in Pennsylvania, because in those days, of course, we had censor boards, we had state censor abortion. We had a few very powerful city censor board, Chicago, for example. But in Pennsylvania, the senator said this is a frightening film. This is as much too, too violent.

Speaker This will frighten Americans.

Speaker And Louis DeRose once said that’s ridiculous. He said, we’ll turn that into publicity. He said Americans are going to be frightened by this. Americans are going to do their duty and they’re going to do what’s necessary. But it never ran in Pennsylvania.

Speaker Well, I guess this part because of his. Added to. I would suspect this was pretty pleased with it.

Speaker I would guess that Lucia was very pleased with it. I think it’s safe to say that. The main line of March of time work pleased or at least did not offend loose.

Speaker And that it was agreeable to him, Soula Larsen, after all, it was a very sound business man. And. But he was an experimenter. He is a man who was willing to take chances. Life magazine published a really earth shaking in its day in earth shaking picture story on the birth of a baby. And in in Boston, Massachusetts, the censors let us let the police let it be known that if it was put on the stands, they would arrest whoever marketed it. So Larson himself went up to Boston and put it on the rack, suddenly on the stand, and the police arrested him. And he said to me, he said it was kind of unsettling at the time. No one likes to be arrested. But he said, of course, we won in court. And Mr. Welsh, the distinguished attorney who later played a part in the Army McCarthy hearings, was the attorney that defended that First Amendment case.

Speaker So what role in the constellation of Tiny? The magazines. What role do you think, march of time? Played or held in that?

Speaker In that instance, I think that in in this galaxy of publications and there were many others, of course, that came along, it played an extremely important role for each time. It never made any money. It just about broke even. But it was worth millions of dollars in publicity for Time Inc. and for its products. Every time it came on the screen, it told you that this was an exciting series, episode put together by the editors of Time and Life magazines. So it had great value of a promotional sort. It had a very fine reputation. It was well regarded. It was controversial. It shook people up. All of which was the intention of time in general in all of its publications in due time. Of course, it passed from the American entertainment scene when war broke out. A lot of the the fun of the march of time ended. That was a total war. And you could no longer criticize government, or at least not in the same fashion. You couldn’t puncture pomposity wherever you found it. And it simply lost a lot of it. They couldn’t needle people anymore. By 1951, its time had ended and it ceased production. In that year, but fondly remembered by its generation of people. And it’s still available in the archives.

Speaker You take a good look at it.

Speaker Go back a little bit about Time magazine and ask you what was.

Speaker What was new and different?

Speaker Time magazine, first of all, was a pastiche. It took a lot of information and news, which it got from other sources and packaged it together. It was an omnibus. You pick it up, you flip through it. And you had different sections devoted to different subject matter. You got the whole week’s work, the whole week event. Nicely summarized in tabloid fashion. It was a small magazine, easy to carry, easy to handle. And it was all done with great panache, with great journalistic style and vivacity. It pioneered a new kind of language. And today you don’t we don’t see this so much with their magazines. We have a different of the the Associated Press Stylebook changes regularly anyway. But time had its own style. And it worked hard to to create an interesting kind of language that would conjure up word pictures in the minds of the audience, of the readers.

Speaker In fact, The New Yorker magazine had a funny cartoon on one occasion which purported to show two editors at Life magazine and one said to the other. Is it appropriate to refer to our subscribers as readers? It was all pictures, of course. And life was life was fabulously successful. Life was a phenomenon because, as they say, you didn’t have to read very much. There wasn’t that much text. It was a new way of telling stories. Photojournalism was pioneered by Life magazine, which had begun just a little bit earlier with time with its incorporation, regular incorporation of photos that would integrate organically with the text. And life was one step further. Of course, it was the telling of complete stories with with photographs. Fortune magazine had its own readership. It was not a big readership, but it was a very expensive magazine.

Speaker It paid its way elegantly, elegantly printed and produced one of the most elegant regular monthly magazines it was ever published. And then, of course, much later, the corporation introduces its sports magazines and then moves into many other different enterprises.

Speaker But the original Time magazine was something you looked forward to. Just the cover alone was stimulating. It was usually a photograph. Occasionally a drawing of someone famous or infamous, preferably infamous. And you could among politicians, of course, you could gauge who was on the up and who was on the downside, depending upon how often they ended up on the cover of Time magazine.

Speaker Why did we got into the into life a little bit? Why did.

Speaker Life’s so out for form. Magazines like Look magazine. Right.

Speaker It wasn’t the only you know, life wasn’t the only picture magazine, but it was the first. And it pretty much set the style for magazines like, look, Collier’s, of course, was more or have much more text. Saturday Evening Post, much more text with lovely illustrations. Some of them drawn look came closest and and there were other. Today there are we have inheritors of their style picture magazines with very little text. They don’t take that much. They’re fun to look at the photos grab you. The paparazzi have gotten good images of famous people for you. And this is all what what Life magazine began with in those days, a little bit more discreet than today. In fact, in one of their celebratory publications called For Hours a Year, which was the experimental pre Life magazine issue, they published a few photographs called photos. Maybe we shouldn’t have printed.

Speaker Tell me tell me more about that.

Speaker Look, for a year after approximately a year after the march of time had been released and it was clear that it was a success. They decided the company decided to celebrate it with a handsomely printed book, large format, of which not too many copies were printed. I don’t know, perhaps five hundred, maybe eight hundred or so. And these were designed as giveaways to advertisers and VIP people in government. Important people, people of consequence. And it celebrated the march of time and all of its work. But they said at the at the company, while we’re doing this, let’s try out some of our ideas that we want to use in Life magazine and especially our ideas of pictorial journalism, the layout, the the great use of photographs and the minimal use of text. And so we have a very rare book. Today, there aren’t that many copies of it remain, which was the prerelease at prerelease experiment for Life magazine. And one or two of the pieces, as I recall, were used in the early Life magazine. But I think one on the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Speaker Great.

Speaker Besides, we’ve met, we’ve talked about ramparts, we’ve talked about inside Nazi Germany. What are some of the more memorable?

Speaker Please let me welcome. Let me take a look here at some of the titles and the over Fred.

Speaker The subject of.

Speaker The subject matter of the march of time was diverse and numerous, specially in the early years, because you’d have four or five different subjects in that 20 minute release. Some of them were funny. Some of them were charming. Father Divine, who was a religious leader, whom the march of time liked very much. And he did two shows for him. He moved into an estate next to Franklin Roosevelt, which had previously been owned by a Republican family. And they got Mr. Roosevelt to say, well, it’s nice to have good neighbors there. Father Divine was marvelous. Some of the people, of course, were very frightening. Huey Long and they would talk people into saying the darndest things on camera. Highly offensive things, things the statements that would reveal what they were really up to and what what their their their real political motivations were racist statements. Brother, not yet. I’d rather not give an example. Yeah. Occasionally they would interview someone with very strong racist’s point of view and they would they would introduce it into their commentary on camera later when they sat down and thought about it. They’d tried to get the footage back and then it was too late. March your time was sued many times by different people. They attacked a quack named Baker, who was a cancer quack and exposed him. He sued them. He lost. They made. They made pictures about everybody, everybody. They made them on many political subjects. The quality of food, which was the French fascist organization, made them about the New Deal experimentations in the economy. And, of course, the Tennessee Valley Authority and the state of homelessness in the state of public health. Everything that would impact the lives of the common man they dealt with. I asked Roy Larson, what was your favorite? And he said it was an early issue called the Veterans of Future Wars.

Speaker And he said, we discovered that there was an organization at one of the Ivy League colleges of that name. And these were young men who said publicly and no, usually we’re going to be drafted for the next war. Next war is coming up pretty soon. And there’s nothing we can do about it. And we will go to war because we’re good citizens.

Speaker And some of us will come back and some of us won’t. And we want to have our bonus now, the Veterans of Future Wars petition Congress for a veterans bonus. Then before war began, while they could still enjoy it. And while those that weren’t going to come back could have their bonus.

Speaker Are there any that you particularly are fond of in terms of its.

Speaker You said recreate some of the shows were a little bit or tray, they were a little bit morbid. There was one about a deep, deep Blair, the French executioner who guillotined people in the 30s, the French still executed by means of the guillotine, and they followed him around Paris. Secretly, they also had a double that looked like him, but they got some authentic shots of him. They had a pretty scary recreation of a guillotining, and it only lasted for about four minutes or so. But that was their grand ginga old piece for the issue. Everything was you never knew what you’d find in the march of time.

Speaker Let me see if I have one or two others. There’s so many good one. To heal.

Speaker One of my favorite March time subjects was called an American dictator. And it was about General Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic who had for many years been supported by the United States government and who was a full blown and quite dangerous dictator.

Speaker March of time called him the dictator against a dictator that ever dictated. And they had some authentic footage that Fox Movietone had taken of him, a few longshots medium shots and military parades and the rest of it. They staged in New Jersey and New York City with sets and with someone who looked pretty much like a General Trujillo. And they had dialogue sequences and some of them were really rather amusing and some of them weren’t so amusing. Apparently, Trujillo had succeeded in pulling off an assassination here in New York City. Some of his opponents. And they staged that as well. Very nicely sewn together and ending, of course, as they all did with Westbrooke man. Or he wondering what this portends. No man can say. Time marches on.

Speaker Right.

Speaker So if I could ask again a general question. How, if at all, do you did Henry loose change?

Speaker Uh, the media’s role in American.

Speaker I think Henry Luce changed permanently and dramatically our expectations about journalism, especially when you when you look at the origins of journalism and newspaper publication in the 19th century into the 20th. By today’s standards, it was pretty dull. There were no pictures. Even the the layout, the typography was doh, doh, doh. As we enter the 20th century, we find a number of powerful press barons who are trying to Hearst and Pulitzer and others were trying to bring some vivacity to journalism and lose, I think is is the master of this who brings not only vivacity, but sophistication.

Speaker TIME magazine products were class magazines. They were popular. They appeal to the the ordinary American who wanted to know more about the world. But they were very well-made. They their topography was excellent. The photography was good, meticulous, high powered work went into the editing of it and especially the humor and the sophistication. I think what we’re going to remember Henry Luce for.

Speaker Do you think?

Speaker And this is speculation, but I’ll throw it out anyway. Do you think that when he started TIME magazine, he and Britain have.

Speaker Do you think he envisioned that this was a vehicle for him to be personally influential and powerful?

Speaker It’s hard to know what Mr Luce’s personal drive motivation was. He was, by nature, a driving personality devoted almost 100 percent to his career, to his work, to his vision. I don’t think the man was that into himself that much, but he was into his ideas. He had certain things he wanted to accomplish in journalism. He had points of view about political matters which were strongly held. And I think that the dynamism and the will that he brought was more to ideas and to his work than it was to self promulgation.

Speaker You talk about his ideas and his vision. Can you describe for me what he felt like his what this was this vision?

Speaker And Ray Lewis once said that he was an orphan. He had been born and brought up in China, came to the United States, regarded the United States as his home. He said, I don’t have a home, a real home in which to live. But he said, this is my country and this is the American century. And America will lead the way.

Speaker I think he believed in this country and then everything that at least according to the books we believe we are dedicated to and that we will even. I believe he will. He considered him, first of all, an American one thinks of us Citizen Kane, who said who was a composite of many publishers and who said, I am I’m American.

Speaker That’s what I am, only an American.

Speaker And of course, one remembers that the march of time was parodied in Citizen Kane. I asked some of the people I’ve known, many of the people who made Citizen Kane, and I asked them, what do you think about that?

Speaker And.

Speaker They said we felt that it was just a natural because it was parodic. It’s a parody. The March of time almost parodied itself. Then I asked people at the march of time, what did you think about that? Were you offended? They said, Oh, no. They said we were very flattered that Wells would use that. And of course, Wells had performed as an actor in the radio version of the March of Time and used and brought many of those techniques. Overlapping dialogue, for example, people interrupting one another, very difficult acting assignment to to perform this way, which he brings to kind of fruition with his men from Mars broadcast on Halloween a few years later and in the Mercury Theater Playhouse.

Speaker What role do you think?

Speaker Time, life and the march of time. Played during the war, the Second World War.

Speaker I think the task which time set for itself was to confirm those values which were appropriate in time of war, to support the war, which was very much Mr. Lucias intention, and to build morale, to interpret it especially photographically through Life magazine, to report it. But, of course, in a in a generally supportive kind of way to interpret it, we must remember that motion picture footage, newsreel 40 during the Second World War was heavily censored and much of its footage of really terrible conflict, especially in the Pacific, SkyPan and the rest did not reach theaters until weeks or even months later, nor did the statistics reach the public. It was a different kind of war. We were a different kind of people. It was a different kind of country.

Speaker Is there anything that we ran through a lot of? Right. Right. If there’s anything you feel we didn’t know hit, you know.

Speaker A lot of interesting anecdotal stuff, but it would take us off into the march of time and away from from Time Inc.. Mark, your time was really. It was an enclave. It enjoyed more than any other unit at time. Independence wasn’t even in the same building. It was way over on the west side of New York. And that was the way they wanted it. They did not welcome Mr. Luce’s visits, and they were very few of them. They loved Roy Larson because Roy Lausch loved the march of time. It was run by Louis de Rosemont. And I kind of doubt if the company, with rare exceptions, ever censored or even inquired as to what the next episode was going to be and what it was going to look like.

Speaker Right. So here’s a question. OK, why don’t we vote for Roberto? These room, Tom.

Speaker Andrew.