Speaker So tell me what triggered the New York Times phase, he wrote.

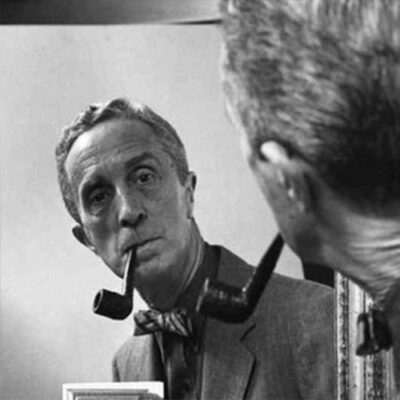

Speaker Yeah, in the early 70s, there was an exhibit of Rockwells. Well, let me start that again. It was an exhibit. It was a book. What got me up there. And when I met Rockwell was that Abrams, the the art publisher, had put out a gigantic book of of Rockwell paintings, reproductions. And it was one of the best selling art books there’s ever been. They were totally surprised. And The Times looked at that and said, well, let’s, you know, find out who Norman Rockwell is. I mean, he was a name nobody ever really associated a person with anything. But it was the fact that there were people who were beginning to talk about him as a serious artist. Well, he talked himself about being an illustrator.

Speaker I mean, that book represented a big sort of turnaround. Right. Or in the way people were thinking of Rockwell’s talk and talk about the book a little. What was on them?

Speaker I don’t know much about the projects. The. I mean, I don’t. A guy named Thomas. Where’s he from?

Speaker The Brooklyn Museum.

Speaker The. And what did it cost? I don’t know. I’ll get them. I. Oh, kay.

Speaker Well, it’s really the point that, you know, the publication of that book represented the right.

Speaker Changing how people ask, asking the question again to give me intentional or whatever.

Speaker Tell me what this book was that kind of represented or triggered a change in how people started to think about Rockwell, the late 60s, early 70s.

Speaker It was the early 70s. And there were a lot of books out on wife. At the time, there were lines in New York at Wyeth exhibit and one the people saw. That was Harry Abrams, who who created the Abrams art books. And he decided why. Why not publish Norman Rockwell as well? And they put out a book, a 60 dollar book, a coffee table book, and they figured it would sell three or four thousand copies. Well, it was selling in the hundred thousands almost immediately. They couldn’t print them fast enough because whatever his virtues as an artist, he obviously had touched the American people for a long, long time. And the text of the book was done by the head of the the Brooklyn Museum who explained his thought that, in fact, Rockwell was a ranked artist, although I must say Rockwell never considered himself a ranked artist. He thought of himself as an illustrator. He did jobs that he was paid for. And when I went up there for The New York Times, one of the things I was supposed to do was to see if he’d do a cover for the New York Times magazine on the story about him. And I remember it was one of the many surprises that I had when I met him. He said, well, you know, have your people call me and tell tell me what they want, because the fact is he was in that way. He was like a shoemaker or a great carpenter, whatever you wanted. You got it with Rockwell’s name and the touch he had. I mean, he was a human whose work there was. It didn’t go very deep because you could get everything at the first glance. But that was the reason people loved him. They understood him. And to a large extent, he understood them.

Speaker How did you personally think about him when you got this assignment?

Speaker I.

Speaker Well, I do. I mean, what I know about art is not very impressive, to say the least. I I had been complaining that I was doing nothing but presidential candidate pieces and things like that. And I’d love to spend time with a human being rather than with a politician. And they said, well, would you go up and see Norman Rockwell? I did. And I loved it. He was a he was a wonderful companion. He had a wonderful life set up. He had a relatively new wife who is an English teacher. And they had this wonderful life. They had the Saturday Evening Post Life in Stockbridge, which if you look at it in a certain way, is a Saturday Evening Post town. And then when I like anybody, I mean, I you admire people who do what they do well. And if they let you watch them even, it’s a kick. But he would there was a sign of him or a sign of his new wife that was quite different than I expected. So his his banter was about things like what a jerk he thought Richard Nixon was and how there was nothing good to find in the Vietnam War. Why were we doing this? And why are people asking me to paint about this horrible thing where we’re ruining these people’s lives? But that never showed in his work or if it did show, it was just doing a glimpse of it.

Speaker And what was that story about his wife, Molly, supposedly telling him he couldn’t paint the Marine kneeling? I don’t remember the story. Well, yes. You said that she apparently he was asked to paint a picture of a Marine kneeling before villagers in Vietnam. And she said, you can’t do that because people won’t like him. Well, because you know who asked him to do that?

Speaker You know where that is.

Speaker I don’t know what kind of in your article that is now.

Speaker Although he was asked to paint a Marine in Vietnam kneeling over to help a wounded villager. And the implication, Joe, I always the Marines wanted to do it.

Speaker OK. OK. I ask the question again. I get it.

Speaker OK. Remember the story that he was asked to write to paint a picture of about Vietnam and his wife discouraged him from doing it?

Speaker If you could write a story in those days. So, again, I. Around the time I was there, the Marines, the U.S. Marine Corps asked him to do a painting for them. And the painting they wanted was a an American Marine kneeling over to help or hurt Vietnamese kid. When Rockwell got home that night, he talked to his wife, Molly. She said, you can’t do that. The next day that I saw him and he said, I you think I should do. He said, we’re not really helping those people in Vietnam, are we? I mean, we’re not doing anything for them. And I said, well, that’s my opinion. I don’t know what your opinion is. But his opinion, very, very unusual for him was that he would not do that painting. And that was probably the first time in his life that he actually refused a commission because he worked on commission. And again, it was like hiring a good carpenter. There was nothing he wouldn’t do up until that point. And I think it was because Molly, his wife, was offended by the idea itself.

Speaker But in general, you pretty you were clear that he the ideas did not originate with him.

Speaker He knew that some he wouldn’t work, as you say.

Speaker And I think I think the people who denigrate him as an artist are really thinking about art and soul and depth and pouring out what there is inside you. Whatever he did, Norman Rockwell didn’t do that. He did not come up with ideas himself. He did very, very few pieces of work in his entire life where the idea was his. He wanted to know what art directors at Adjei agencies wanted. He wanted to know what the Saturday Evening Post wanted. In my case, he wanted to know what The New York Times wanted. And then he would give you this perfectly crafted Rockwell of your subject, except when the Marines asked them to show a Marine helping children in Vietnam because either he or he or his wife or he and his wife didn’t believe that was what Vietnam was about.

Speaker He was 77 years old. And I had the impression because I was there when that was going on, that that was the first time he really approached anything. As a matter of conscience, his most famous conscious painting in Little Rock was done on a commission. He gave them the picture. They want a little black girl. Big soldiers taking her to class. He had not seen it. He had looked at newspaper photographs, which is what he generally work from. And but the. I don’t get any depth of the pain. You get it. You get a you get a wonderful moment with a Rockwell painting like that. But it doesn’t leave you don’t go away thinking about race or about Little Rock because you’ve seen all he has to say.

Speaker Speaking of race, I mean, he really didn’t paint blacks as other than servants prior to the 60s.

Speaker Do what? Well, I and I asked Rockwell why there were never blacks in his painting except for a little rock painting, basically. And he said because editors don’t want. He had worked for years for another name, Ben Hibbs, at the Saturday Evening Post. And the standing order was, don’t put black people in your paintings, makes people feel uneasy.

Speaker He was a man who wanted to please.

Speaker Yeah. I Brockwell never believed deeply in his own talent. I don’t think I. And therefore it was more important to him than it might be to other painters to please people to make them happy, because that was he was living off that kind of recognition rather than recognition in the hearts columns of The New York Times or with the Museum of Modern Art or whatever. I mean, his sustenance and his constituency were art directors, editors and ad agency executives.

Speaker Did you get any sense of frustration on his part that he wasn’t more widely respected in the art world? I.

Speaker As far as I could tell. The lack of critical acclaim did not bother him at all. He did see himself as a craftsman. I told him a story or someone told them a story about someone wanted to trade a wife for one of his paintings. And he told me he thought that was insane. Why is as an artist. I’m just I make posters. So I don’t think he was pained by public criticism, such as it was, of course, and if there are 200 million people in the country at that time. Ten thousand of them probably knew enough or thought they knew enough not to like Rockwell. The other two hundred million loved him. He created an America that we wanted to be America. It may have been a myth. He thought it was a myth, I think. But it was. It was the kind of wallpaper of the United States for for half a century.

Speaker Do you think he purposely painted a male family knowing it was a method you think something subconscious? Did he believe it in any sense? Design?

Speaker I. If you if you look at his work in as far as where it came out of and the wife’s work and his father’s work, even into the 1970s, Norman was was painting an extension of magazine illustration of the ceiling of the century, basically before photography was widely used, so that if you look at the pictures in the old Collier’s and magazines like that and look at the advertisements, they were the same. The advertisements were done by painters or illustrators, as was the copy in the magazines. And that’s where he came out of. And he didn’t change much after that. But you can see the precursors of his work in the advertising of a magazine and say, 1910 or 1915.

Speaker So he found a formula that worked or that sold the kind of guy he was, he found.

Speaker Early on, he was only a teenager when his first off was published. Early on, he found he found out what people wanted. And he also, because of various things in his background, wanted money, and he can say he considered money a lot. Not that he spent huge amounts of it. But I think that I imagine you grew up in artist families with with all round, you know, you know, more than a little by people who don’t have any money in their pockets. And he was certainly determined that that would never happen. But his view of money and its value, as far as I could tell, would never change. When when I asked him if he’d do a cover for the piece I was doing for the Times. He said, well, you know, something like that, of course. Five thousand dollars. So I allowed a site of The New York Times just might be able to afford that. But to him, that seemed like a lot of money.

Speaker Like I said, 1971 is a little more money than it would be today. What is it all about? I mean, the Senate behind us, Main Street, Stockbridge. I mean that. What is it about that kind of image that he painted that’s become such an icon and now associated with America’s identity? I mean, it taps into something that we want to believe about ourselves, right?

Speaker Well, I mean, you do. You know, he and Walt Disney had the same salable vision of America. I mean, the main street they put up in the Disney Land, which I guess is from a town in Missouri where where Disney grew up, is is not that different from Stockbridge. That’s the way I think. That’s the way most of us would like to see America. And B, B, L and many do. And Rockwell, I think, and Disney were, too. Who did they. Both tough businessmen. I mean, he wasn’t as he was an a builder in the way that the way that Disney was. But they they both. That was America to them. And they’re right up there as the guy that you could call them, the mythmakers of America. But they were also the definer of America. I’m talking about basically a contemporary of his. I mean, Walter Lippmann gave you one view of what America was. And Norman Rockwell gave you quite a different view. And you’d have to have a real bad hair day to prefer Lippmann’s view of the country. To Norman Rockwell’s, even if it was an exaggeration or glossing over. Of what? Of what the country. Was and look like particularly in that period, he felt the Vietnam War, doing stuff about the Vietnam War was a hell of a lot different than doing it about World War Two, because he did get, even at the age of 77, had real doubts about what was going on. He was not a man without opinions. And he and his strongest opinion, at least when I talked to him, was about Richard Nixon. He despised Richard Nixon. He had painted him several times. But his gut feeling, which he what he told me about walking through the Plaza Hotel once with Nixon and Nixon, he was going to paint everything up into a room and Rockwell was picking the room for the light and what not. Nixon was with him and Nixon was saying hello to everybody, particularly to when they got upstairs to maids and that kind of thing in the Plaza Hotel. Rockwell knew that that was all for his benefit. And he told me this is all the man cared about was becoming president. He says, I’m not sure that there’s anything there. On the other hand, it was great fun, great fun to talk to someone about these things when he painted Lyndon Johnson at the same time Peter Hurd did.

Speaker And it was the painting that Johnson hated and took down. And then people said, Johnson, what do you want? He would point to Norman Rockwell painting of him. And I said, What would you do that was so pleasing to him? You said, I made his ears smaller.

Speaker Rockwell, the myth maker, know Mike Tyson wasn’t around.

Speaker He could’ve shortened this year.

Speaker What’s wrong? We’ll have more sophisticated Ballan some ways. I think that he.

Speaker No, I don’t think he was too sophisticated then. Or to add or add. He was he was not educated, basically, but he had married to one his wife, Molly, who had never married before and had been an English teacher her whole life and who was politically liberal.

Speaker And he spent the man was a workaholic on a on a stunning level. So that really at that point in his life, he spent most of his time, if he was with other people, since he generally worked alone with Molly, his new wife.

Speaker And I think that just as he took his signal from the editors who wanted a certain kind of painting, he took the signals from Molly about what the world was on a level that he had never thought about. And he said to me, which I thought was a touch, sad because I, like everybody else, love them. He said that when he painted the Four Freedoms I during the during World War Two, he believed everything in that painting. And he said I could not do that painting again because I thought all those things were going to prevail after the war. And then other things happened. And he said, I feel sad about that. And I think the reason he felt sad about it was he wanted it to be. I mean, if if we believed the myth, if he engendered a myth in the populace, I think to a large extent through most of his life, he believed it more than we did.

Speaker And I guess people certainly at the height of his fame do believe it. I’m in the 40s, 50s.

Speaker Well, yes, people believed it. I mean, what which came first, the pain or the anger of the. I don’t know that. But he reflected at that point in time, particularly going into World War two, that and probably in the years immediately afterwards, he was projecting what was the consensus view within within the United States. And I don’t think it was. I suppose that the difference being an artist and illustrator, he represented that view. He didn’t create it. He was not an art. An artist on a certain level could create. I mean, Monet could create a reality by his work. I don’t think that Rockwell had that kind of power or talent.

Speaker So just to be clear, you I mean, you’re not saying he was a real us in the sense that he painted the exact reality, but he painted an emotional truth that people thought.

Speaker I mean. I know. I mean, he paint. Who’s quite a realistic Peter, after all. And he used models and saying people would appear and he was painting the reality of those people in a setting that had been suggested by by someone else.

Speaker But I mean, what I’m getting at is, did he paint real America? He didn’t paint the depression. He’d never painted violence. I mean, did the America Rockwell painting ever really exist?

Speaker I.

Speaker I feel if someone asked me, did that America exist, that it really was the one he created exist? I think I would say yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Clause because the American mind is is as good a landscape to describe America as as Massachusetts is. That reality did exist. And if it didn’t exist on the main street of Stockbridge, it existed in the minds and hearts of millions upon millions of people.

Speaker Sorry. Can quickly take that again, please.

Speaker Those are always there. Do you mind picking it up from. You’d say, yes, Virginia, there is a single.

Speaker I if somebody asked me, I’m no art critic whether that was a reality to. Let me start again.

Speaker Was there a reality to this painting? Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Clause because the minds and hearts of the American people, which is where his landscape really existed, is just as real as the streets of Stockbridge, Massachusetts. So I think that reality did exist. It wasn’t a physical reality.

Speaker He gave it a physical reality, a kind of Potemkin America. But that doesn’t. I don’t know whether people believed in Potemkin, but I know Americans, many of them believe in that America.

Speaker A Santa Claus.

Speaker Still today them from eating is if you’re. I yeah. I mean, he allowed it. What what. The great thing about Santa Claus is that the kids believe it. And then I get to a certain age where they don’t. In that way, Rockwell is better than Santa Claus because people continue to believe it after their eleven so that he is a. These samplers were off the hook. I mean, that’s. But Norman Rockwell is as real as Santa Claus.

Speaker And and almost as enduring when you go to his museum and Stockbridge, him in the crowds mean, you know, the paraphernalia of the commercial. I didn’t know that rockfalls. Pretty amazing. Do you have any sense of, you know, all the commercial? No. Like I say, I don’t know. Life. I mean, I know that I’ve had enough of this.

Speaker I mean, you see what happens with Dr. Seuss. You know, some of these guys in this case, they’re men, shoes. These people die. Their families cash in on it. And Rockwell, I don’t think would have done that in his lifetime and not really. He didn’t dislike people, but people were in his way when he was painting. He would paint from light to light during the day with just a break for for lunch with his wife for a short lunch. And he had very much that sense. I mean, he was a workaholic. He had that sense of the day would come when his hand wouldn’t be able or his mind or his I would not be able to do this. And he was determined to hold that offer as long as possible and to do as much as possible before then.

Speaker We’ll see. Enjoying his success, this fame at that point.

Speaker I. I think you enjoyed the fame, and I think he enjoyed being Norman Rockwell and I he. He didn’t he didn’t go to great pains. I think was a genuine humility, but he didn’t go to great pains to to aggrandize himself here. He said, and I think to a large measure, thought that these people in New York and elsewhere talking about him now as an artist like Why or Winslow Homer or whatnot. I don’t think he believed that. And he was right. He wasn’t an artist on that level again, because those people had a depth in their work that never left you. And you had to look at their work for a very long time and try to put yourself in the artist’s place and in the situations place and transform yourself as a person. His paintings were like a mirror. You walked up there and you saw it. And that was it.

Speaker And yet his paintings, when he’s the best known American visual artist, probably.

Speaker Is he the best? Well, he had, you know.

Speaker He was the love towards you. He was truly an artist of the masses. But the masses in this country are not poor people or people looking for a new system. The masses in this country are the middle class. Middle Americans who believe in or want to believe in or think they remember an America that looked very much like the thousands of canvases that Norman Rockwell.

Speaker Did you think Rockwell played the role of television now plays and was. At the height of his power. Well.

Speaker I don’t know what weather Rockwell himself was. Was that. I was as important as television, but through most of his career, the magazines that he worked for were television, they were the national mass media. We had no national newspapers. Radio had become national. It was a different kind of medium so that it was not like painting covers for a magazine today. It was like having prime time, the cover, the Saturday Evening Post or look or were alive wherever he worked at a given time. That was the mass media of the day.

Speaker All right, let’s come first. Let’s check.

Speaker Do you did you talk to him at all about his involvement with the famous artist school?

Speaker Well, I talked to him only in terms of money.

Speaker We were having a conversation about money, about how much you’re paid to do this. And he and he brought up the fact that there had been a tremendous run up in the price of famous artist schools, which I guess he was a founding member of, but that had gone from sixty two dollars at its peak. There was a recession and in the early 70s it had gone from sixty two dollars at its peak to eight dollars. So however much he owned and had lost 90 percent of its value, I don’t think he felt great concern about that. I mean, he had he made a lot of money. He was making a lot and he made more than he could spend. And actually, he didn’t want to spend. He wanted to work.

Speaker Once our scandal around his involvement with some sort of school, because we’ve been trying to get some research and it’s sort of unclear to me, not in my life, to my memory of what I have no idea.

Speaker I mean, there’s famous artist and famous writer. I don’t remember. I yeah, I have no memory. And if I had known about it, obviously, I would have done something on it. But I don’t. You know, I think it probably was like the Planet Hollywood of its day and that the put do the principals actually know how it’s being run? I doubt that. So is this Sylvester Stallone of of famous order schools or something like that? I don’t think he made. He made his decisions. I know he didn’t make decisions. He painted. That’s what he did.

Speaker Just to go back to this issue of the man versus his image. You quoted Ben Hibbs, as you know, regarding his naivete or lack of it. Do you remember that?

Speaker Well, there were those and then, you know, Saturday Evening Post who dealt with him a great deal. I thought that beneath that bumbling and humble of spirit exterior, there was a real tough businessman there. My own impression was that that was somewhat exaggerated or perhaps that role had passed to his wife. I mean, there are a lot of us, a lot a lot of men and some women who are freed from from kind of financial decision making and real decision making by the fact that their spouse takes care of all that. My impression was at the time, I know that Molly took care of all the.

Speaker Do you remember the Hibbs quote exactly that? Well, I forgot about as naive as Nikita Khrushchev.

Speaker I’ll get that in for the. Well, there were those who thought that that exterior was just an exterior. Ben Hibbs, who probably bought more of his work the end of the Saturday Evening Post, told me that he thought that Norman Rockwell was about as naive as Nikita Khrushchev. I didn’t go, I use that, I didn’t fully believe that. I think that his wife handled that that account for him.