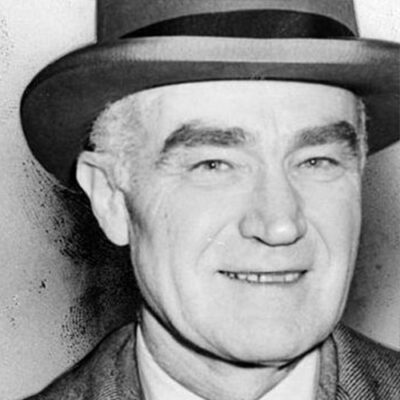

Speaker Slated. This is our interview with Richard Stolley. On December the 11th, 2002.

Speaker And before we get started, if you could just briefly outline for me the different positions you’ve held within time since you started.

Speaker Briefly.

Speaker Whenever whenever I ask this quite like when I was in the Tokyo bureau, well, I began as a reporter in New York, then spent about 15 years in bureaus, chief of the Atlanta bureau chief for the Los Angeles bureau, chief of the Washington bureau and then chief of all European bureaus. Then I came back to New York as system managing editor and then life died. I was the founding editor of People. I held that job for eight years. Then I was the editor of The Monthly Life for three years. I worked in experimental magazines for a couple of years. Then I was editorial director of all the magazines and then I retired. And I’m now senior editorial adviser, which is a fancy name for a consultant.

Speaker Lifetime, lifetime, and what year was it, 72? December seven. Seventy two. Last week issue.

Speaker Yes. I added to the last weekly issue, which came out later that year.

Speaker Then people started saying, you know, who started in spring of 74?

Speaker And here is Charlie. Hi. Hey, Charlie.

Speaker Yeah, come here.

Speaker Hey, you OK? Yeah. You ready for your close up? OK, you can watch you, but you can’t watch from back there because the camera is supposed to carry a camera is shooting behind a dad.

Speaker I can see myself. Yes. You can get a closer look at that. Well, there you are.

Speaker Charlie, listen. Now, once you get in there, you put your.

Speaker A few general questions about the Life magazine.

Speaker Well, first of all, when you were younger, did life come to your life for a time? Come to your house?

Speaker Life did time. No.

Speaker And what will cut will. I guess what I’m trying to get at is what what importance did life have in kind of the cultural landscape of Minnesota?

Speaker Well, life shows you what the world looked like. I grew up in downstate Illinois and.

Speaker Oh, Charlie. Charlie. Let’s talk about what the time was. I mean, life in these cultural lands.

Speaker Well, life came to people’s homes Friday and there was always a fight to see who would be get the first look at the magazine. And it got passed around. It was it was the way we discovered what the world looked like. I grew up in downstate Illinois. And we knew events were happening. We read the newspaper and we listened to the radio, but we didn’t know what things look like. And that’s the role that life played in America in when I was growing up.

Speaker When it came to your house, did you I mean, were you. The first one to see it, or did you want to be the first one to see you? Were you personally excited when it came to.

Speaker Oh, yeah. I mean, well, we got home from school before my father got home from work. And so we had first crack at it. Yes, I was very interested in pictures. I started work as a professional journalist at the age of 15 and I was editing the sports page for a daily newspaper in town. So I was involved in journalism. Interested in a three or four years before that. And so I. I mean, it wasn’t so much the writing of life which I read the stories, but we were seeing what people look like. What events look like. We would read about the events in the Chicago Tribune, which is the newspaper everybody took then. But we had to wait until Friday to see what things look like.

Speaker What was?

Speaker What was new and different about Life magazine? When it appeared.

Speaker Well, life.

Speaker Life began with the advent of the small 35 millimeter camera and the ability to shoot in available light. You couldn’t cover the world. You couldn’t cover people events. If you had, like, everything like this. And so when that camera came along, Henry Luce used that as as an excuse to to try a picture magazine. He sense that there was a hunger for photographs, for images, for how things looked. There was no way to do it quickly on a weekly basis until those cameras came along and he found the people in the world, the photographers who knew how to deal with those cameras.

Speaker All of this coalesced in 1936 in the launch of Life. It was a huge, immediate success. In fact, it was such a success that it almost bankrupt itself. They expected it to have a certain circulation and they were selling ads at that circulation level. They were selling so many more copies of the magazine than they had anticipated. That it was costing a fortune to put the magazine out and they were recouping only a small part of that through these cheap ads. Well. They caught up soon enough.

Speaker How?

Speaker How much power, how influential was Henry Luce through these magazines? What kind of influence?

Speaker And I guess that’s a multipart question. Let me ask the first part in terms of.

Speaker The people of America, sort of the the middle America that life reached to what what kind of influence did he have?

Speaker Did his magazine have and therefore did he have?

Speaker Well, his influence was felt in two ways, one in the magazines that he started or decreed to be started, and second in the editors that he chose to run the magazines and release, owned all of these magazines. I mean, he was the boss. But he did not interfere with the magazines that he started, with the exception of the political opinions expressed in the editorial pages. Those opinions were his. So they he had to agree with them. But in terms of the stories that the magazines publish a life, for instance, he was interested.

Speaker He liked the magazine, his. Sort of sense of pictures was not particularly good, but he did have a sense of story sense in a new kinds of stories that he thought would appeal to Americans. And I don’t think we should simply talk about middle Americans or maybe middle Western Americans being one of them. They were they were not that much different from Americans in the south and East Coast and West Coast at that point.

Speaker But Lou said this genius for the popular tastes and I and and use popular in the sense that we knew it then. It had not been as debased as that expression now.

Speaker He in life came along at a time when America was beginning to. Generate strength and influence in the world and in America began getting interested in the world. We gone through a long period of isolationism and concern about our economic futures and all the rest and about the time that he started life.

Speaker We had a war brewing in Europe. All kinds of intrigues are going on in the Pacific. Americans would read about them in the papers here, about them on the radio. And life came along to show what they what they look like. But loose. Lucy always complained that he could never get the stories that he wanted done in the magazines.

Speaker He would come down with suggestions to the editors and they’d always treat him very, I think, sensibly and politely. One of the things that you learn when you went to work at Time, Inc., is you called everybody by his or her first name. Now, can you imagine I was 25 at the time calling Mr. Henry R. Luce. Harry. That was a hard swallow, but if you called a Mr. Loose. No, no, no. Harry. So we call him Harry.

Speaker It’s interesting that I can imagine that being very hard for somebody else to say. Are you kidding? That it’s I hear in the kitchen I would be close to Tina.

Speaker Close the kitchen door, would you, please?

Speaker Yes. We can hear that rapping noise. OK. Thanks.

Speaker What was he like as far as you knew? I don’t know how close you got to.

Speaker Mr. Luce and I were not close, but I saw him a number of times, he liked to. I spent most of my career at life in bureaus out as correspondent in this country and overseas. Luce liked to visit bureaus. He wanted to know what was going on. I want to hear firsthand from correspondents.

Speaker So I ran into him on two or three occasions in the Washington bureau, saw him again in Los Angeles. What was he like? He was.

Speaker Imposing had very impressive eyebrows. First thing you looked at when you saw him, untamed. He had a barking way of speaking very direct, a little intimidating. He was extraordinarily bright and his curiosity was just infinite. Always asking questions about this or about that. It was a famous story. He got off the plane in Denver to visit the bureau. And that was before we had ramps. I mean, you walked down onto the tarmac and walked, he got onto the tarmac and swung his hand up there, said to the bureau chief named those peaks.

Speaker Tell me tell me about the name those Peake’s syndrome or whatever, because that’s a.

Speaker It sort of was sort of the terror of buro. Chiefs everywhere.

Speaker I guess it was all part. Well, it was.

Speaker I was part of Harry’s schtick. I mean, one is it was genuine curiosity. No question about. And he wanted to ask questions as soon as he got on the play. Want to know. You know, what mountains are those.

Speaker And. But it was also a way of sort of rocking people back, and he was smart enough to know that once rock back then you started to get aggressive and smarter and brighter or you prepared for these. Now, there’s a wonderful story about the L.A. bureau chief who had just arrived in L.A.. He did know one peek from another and he knew Luce was going to start asking him questions soon as he got off the airplane.

Speaker So he rehearsed the drive from Los Angeles Airport into the bureau in Beverly Hills. Did a tour three times New Al Jolson Memorial over here. This was Howard Hughes’s factory here, Santa Monica Boulevard. He was all set. Lewis got off the plane, got into the car. The head for the bureau, and here he is. No, no, no, no. I know this way. Let’s go that way.

Speaker Poor Marshall had no idea where it was going.

Speaker So what you’re saying is that that it was it was a fairly routine that when he arrived someplace one could expect that they were going to be grilled from.

Speaker The trip into town about what everything was he.

Speaker Yes, but that was just the beginning. He would get into the bureau and then would have a lunch and or dinner with all of the correspondents.

Speaker And this interrogation would go on. He would always meet with important people and whatever.

Speaker So the mayor and the governor and and businessmen and all the rest. But he was very good. He always reserved a lot of time for the men and women in the bureau’s. To find out how they felt. Not about what not only what was going on in that place, what how they felt about the magazines. He would ask them. He was very blunt questions and he expected very blunt answers.

Speaker Well, that actually brings me to a point, which is that it seemed to me, or at least one reads about that he often.

Speaker Or his. His editors.

Speaker Often hired people whose politics were really quite different from his, you know, in being the. Dyed in the wool Republican. Was there a lot of people on his staff? Quite a bit more liberal than he was.

Speaker Why did he do that? And what kind of dynamic did. Well, I’d.

Speaker I mean, he presumably knew this was going on, but I don’t think there was any conscious effort on his side. He knew there were bright journalists out there. He wanted bright journalists. He knew that he could control the the political atmosphere or certainly the political voice of his publications. And as long as he could do that, he wanted good writers, good reporters, and if they were more liberal than he had, it didn’t bother. These liberal writers were not the ones who were writing the Life editorial every week, however. I mean, that was very clear. That was Luce’s point of view. But he was he he liked bright, lively people. And in their political where they stood on a political spectrum affected him only if he saw that it affected their reporting and their writing. And and most of these journalists were either good enough journalists or smart enough about their own careers not to let that intrude.

Speaker Now with.

Speaker The thing about A you were a reporter for like. And with life being a photo.

Speaker What role did what role did a reporter have for you?

Speaker Did it seem to be a.

Speaker So the secondary role to. The photographers or.

Speaker What I assume being a reporter for life is different than being a reporter for.

Speaker Sake of being a reporter for life was. It was a terrific job, particularly if you’re in a bureau. Now, you did work with photographers and pictures were king. If you didn’t get pictures on a story, it didn’t matter how great your words were. They they would never see print. But.

Speaker The journalists, the print journalists who work for life were very important because if they were good, they developed a picture sense and they became in many ways what you would call a television producer now. They went out. They set stories up. And many times there was a guy, the photographer, into the situation. Then a photographer take over and use his eye to get what he needed for the story. But the reporter and photographer formed in the best of situations, form very close teams. Photographer would suggest certain picture ideas. And then of the I’m sorry, I’d say the reporter would would suggest picture ideas and picture situations and people who ought to be photograph for the story. Then it was the reporter’s job also that not only to take captions, but get the entire story. Then when it was over, the film was shipped back to New York or the photographer took the film back and you sat there and wrote your story with the captions, filed it to New York. And then, as in the case of time, writers in New York took the material, came coming in from the correspondence and distilled it into the text that accompanied the pictures.

Speaker Tell us, if you would, about your own experiences covering. One important beat that you covered was segregation or desegregation in the South. Can you talk about what that. What events you were part of? You know, you reported on what what it was like to be a life reporter there at the.

Speaker The first really important bureau assignment I had was Atlanta, which was the center of life’s coverage of the desegregation of public schools. You have to remember that Lucille was a dyed in the wool Republican, but he felt very strongly about civil rights and life and time particularly would not have taken the stance that they took on this. On the subject of civil rights, if Henry Luce had not felt the same way and had encouraged the top editors to do the kind of coverage that we did. Life again was. Was so critical to the coverage of civil rights because.

Speaker It showed what was going on down there. You could read about.

Speaker Police dogs attacking segregation, desegregation is in the streets of Birmingham.

Speaker But it wasn’t until we saw those pictures that America was so horrified. It started in really in 1956 when I went down there.

Speaker It was two years after the Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling which desegregated, which called for the integration of public schools. We were beefing up the Atlanta bureau. First thing we did, we produced about a eight part series on the subject of segregation.

Speaker Which had to be okayed by loose before we did it. It was a huge undertaking and a one, two or three awards.

Speaker We went around the south finding people who would cooperate with life and talk about their their way of living, about why they felt the way they did about segregation, not only in the schools, but all the Jim Crow laws and all, it was very difficult. Even then, life particularly was anathema in the South, mainly because we did show the evil face of segregation. And they went after life photographers and reporters really more viciously than they did a guy who was carrying a pencil. So wherever we went in the South, we realized that. This was going to range from unpleasant to downright dangerous, and indeed it did.

Speaker The most vivid memory I have is in a small town in Tennessee called Clinton, where the school, the high school had been ordered to integrate. Think there were about five or six black students.

Speaker An out of town rabble rouser and the war such came in and got everybody worked out. This was in eastern Tennessee and there weren’t many blacks there, but.

Speaker The town responded. There was a riot. The photographer and I were lying. On the lawn of the courthouse with.

Speaker Militia line of police and deputies all armed on the steps of the courthouse and and a mob of several hundred who had just been teargassed, some really stupid deputy and thrown tear gas into this crowd, trying to move them back.

Speaker And it turned this crowd into a mob in a matter of minutes.

Speaker And we could hear I could. I was lying. It reminded me of Bill Moreland’s cartoons of World War Two. Well, he says to Joe, I can’t get any lower. My buttons are in the way. And that’s exactly I fell flat down on the. On the lawn and people shouting in the background. Get the bastards guns and kill them, meaning the police.

Speaker It was as close as I ever came to. We thought there was gonna be a gun battle. We’re convinced there was going to be one. And in the middle of that was not a very healthy place to be literally at that moment.

Speaker Fifty state police cars top the hill outside town came roaring in there with sirens and lights flashing and these big beefy state troopers with pistols and nightsticks got out and calmed everybody down. We went through events like that every fall when schools were ordered to desegregate Little Rock. I was in Little Rock. We we had a huge coverage of Little Rock, particularly after the president brought in one hundred and first airborne. We were there. I was there earlier when when the kids weren’t allowed to go in. And then there when, with the help of the paratroopers, the the desegregation of Central High School really did take place that summer.

Speaker I’d spent time in Little Rock talking with a wonderful woman named Daisy Bates, who was the head of that, and Devil ACP. She had the nine Central High School students in her home and she was teaching them.

Speaker The things they needed to know in order to survive in this weight high school, she would go up and confront one of the kids and and say nasty racial things to them and poke them and try to provoke them to see. And in order to train them. To somehow keep their cool when this happened to them. And, of course, it did happen to them. They were remarkable, those nine kids. They stayed in school. They graduated. None of them ever got into any very serious trouble. And they had provocation that you can’t believe in at high school. Yeah, I covered La Rock for about three years, going back to that segregation’s.

Speaker That must’ve been. An unusual undertaking for such a prominent magazine at that time.

Speaker It was very unusual.

Speaker What it did, in effect was to declare to the country that Time Inc was coming down on this side of this question.

Speaker Now, we tried to be as evenhanded as we could. We did some historical the roots of segregation.

Speaker Civil war, the rise of Jim Crow and all the rest, and then the story that I was involved in was the the voices of the Black South and the voices of the white south. Two different stories. And getting the blacks to cooperate back then was not a problem. They knew they knew this magazine was their friend and they assume we were, too. If you ever got into trouble, you were being chased by racists in the South. Then you ran for the black part of town, ironically, because you knew they would protect you. And I did that getting them to cooperate. Was the easy part. Although there was a terrible postscript to two, part of that getting the white was. Challenging. But we did. We got. I remember I lined up the mayor of Greenville, South Carolina, to surprise the hell out of me that he would cooperate.

Speaker And one of the reasons he did was. They really did have respect for life. Now that respect eroded over the next three or four years when it became clear that we were in a cover desegregation in penetrating way. But even then, I think life had that kind of reputation in this country that if they felt. In their own conscience and in sense of well-being, that they could cooperate with the magazine, they would do so. We’ve got a white sharecropper. I got the editor of a small paper in Georgia. We got the owner of a plantation in Greenville, Mississippi, right down there. And the delta.

Speaker It was an amazing series and the we showed them and we quoted them at great length about how they felt about all of this. And it was very honest. So there was nothing snippy or snide about the way that we portrayed the White South. We tried to portray them as they wished to be shown.

Speaker Was there any criticism from the black community about the coverage? Was it uniformly?

Speaker If there was complaints in the black community? I wasn’t aware of it. You wouldn’t have gotten that in the South anyway. The complaints would have come from northern blacks. Some Southern blacks were they couldn’t believe that a magazine like life was tackling this thorny subject.

Speaker And the fact that we had done the voices of the black south, we found one family remarkably in Alabama who had members all over the south, some. One was a college professor, one was a was a grade school teacher, one worked in the V.A. hospital in Tuskegee and we could through this one remarkable family. We could show what had happened to blacks over the last two or three generations in in the south. And it was a very heartfelt and sympathetic.

Speaker Story that resulted in a terrible thing happening to one member of that family.

Speaker You look at.

Speaker So, Salka, at the end, I was talking about me.

Speaker Let’s before we do that, yes, let’s tell me the story about, uh, the terrible.

Speaker Thing that happened to that particular.

Speaker One of the members of the black family that we covered in our series of segregation was a woman who taught grade school.

Speaker In Silus, Alabama, in talk to a county, Alabama. Tiny little town in a unpopulated county that. The mostly cut pulp for the pulp mills.

Speaker She was quoted in the story. Let me back up by saying we had to do this story with a black photographer and a black reporter.

Speaker You could not you couldn’t do that kind of coverage if you were white in the south back then. The photographer was Gordon Parks famous life photographer.

Speaker When Gordon came to Atlanta to go out and do this story, there was no place where you’d even have a meal together. We had to order sandwiches into the office. Even Atlanta, was that segregated at that point?

Speaker And. And if Atlanta was at value, you can imagine what it was like out in Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. We hired a black photographer. A black. We hired a black reporter to go down with Gordon and do this family in in the south.

Speaker One member was a grade school teacher, and she was quoted in our magazine as saying, All I want is justice. That’s all any of us want.

Speaker It hardly seems like a quote that would come back to haunt you, but it did. The reason being that the Alabama had only a few months before decreed that black and white schoolteachers would get the same salary. And this was felt to be a huge step forward for Alabama, which, quite frankly, was.

Speaker The people in that town felt that this woman was. Was sounding as if they were not treated equally. Which, of course, they weren’t. In terms of salary, yes, they felt that somehow she should have acknowledged this.

Speaker The fact is that that I thought she was uppity and how dare she appear in a magazine like Life and and make remarks that they felt were sort of vaguely revolutionary?

Speaker The day the magazine came out. Word raced around town about about her remarks. The there was a remarkable white woman in town who own most of the stores and businesses in that town, and she decreed that that family would be sold nothing.

Speaker From then on, the husband and the family went over, try to get gas for his truck.

Speaker And a man came out and said, Willie, I can’t sell you. I can’t sell any gas. And Willie said, Well, Captain, why not? I’ve always bought gas, sir. And he said, Have you seen that magazine, Willie? That’s a terrible thing in that magazine. So Willie went home and they had not gotten a copy of the magazine.

Speaker She couldn’t buy groceries. And gradually, this economic boycott began closing in on this family. At one point, after a few days of this, the woman, the schoolteacher called Gordon Parks in New York and described what had happened. I was sent down from the Atlanta bureau a day or so later to scout out the situation. I went to Mobile first. I knew this was going to be difficult and. And possibly worse than that. I got a rental car and I asked her, I went to a big paper company that had a branch up in Choctaw County. And I. I’ve met with several of the officials of this company. They already knew what was happening. They’d already heard. And I said, well, I’m going to go up there and try to find out for Life magazine what’s really going on. And I’ll never forget the looks on their faces. And one of them finally said, Man, are you crazy? He said, Life magazine goes up there, you’re going to get tarred and feathered. Well, that’s wonderful piece of advice to get. I was given a piece of advice that turned out to be extremely helpful. They said the only way you can go up there and talk to blacks is if you are used textbook salesmen, they can go to the black schools.

Speaker So I went into a second hand store and bought about 60 or 70 books and loaded in the back of this rental car.

Speaker And drove to Choctaw County. I stopped in a drive in just outside of town for a cup of coffee and damned if the couple sitting in the seats next to me weren’t talking about Life magazine and this story. I thought, oh. I went into town and. I didn’t want to contact the white people at first because I knew once I did that the word would go everywhere and I would have no, I have great difficulty talking with anyone else. I’d been given the name of the of a black schoolteacher. Black principal, I think.

Speaker I went to high school, parked outside, walked in, was seen.

Speaker My presence was reported. People came to the car, looked in the car, saw the books in the back, and dismissed me as a book salesman. I talked with him. He explained to me what was happening.

Speaker He said, you have to get this family out of here because something awful is going to happen to them. I went back and forth about four or five times over the next week or so, and every time I would go back to Mobile and I would report to Life magazine what was happening. Now, I couldn’t go into Western Union and send a message. I’ve done that once before and found out that the Western Union operator had called somebody and had read my message to him. I had to do it all on a telephone. And a stenographer in New York took down these reports. They couldn’t believe me. They didn’t. I mean, the naivety and the in the north about relationships in small southern towns and. After about a week, they said, well, we’re going to send one of the top editors down to.

Speaker Take a look himself. Fine. So this Ed came down. Who’s a friend of mine? And we drove in to. Silus. And at that point, we decided we had to. Talk to the white people. We found the.

Speaker President of the Board of Education, who had suspended this teacher because of her remarks, in addition to the economic boycott, he ran the general store.

Speaker We walked in with with Saddle’s and and it looked like something out of the west of the 19th century. And this man walked over I. He’d been described to me and I said. Mr.. He said, yes. And the editor from New York, wonderful man named Hugh Moffitt, said, My name is Hugh Moffat from Life magazine and I understand we haven’t got a friend in this town. And the guy looked at him. Burst into laughter himself and said, you got that right, Mr. Moffat. Well, we did go around and talk to a lot of white. The man that the husband had had cut the pine pulp for and two or three of the merchants, the very powerful woman who had decreed the boycott. It became became extremely clear that we had to get the family out of there, so the other editors went back to New York and with some difficulty, I found a moving company that went in to they lived in a shack out in the country, moving company, went in there, noticed people watching them from the hills around the this little shack. They moved the material out. The family had already gone to mobile. The woman, mother and father lived there. So. And there are a couple of small children and. That was it. That was the end of the year of the family in Choctaw County. We later. Help helped the daughter when she grew up.

Speaker Life magazine helped put it through college in the north. And the family moved north after that to. They did break up. Unfortunately, they’re husband and wife and the husband ultimately went back to Choctaw County, made his peace. He knew he was illiterate and he said truthfully. I didn’t know what she was saying and I didn’t know what they were writing. And he was allowed back into the community. The rest of the family were outcasts. The rest of their lives.

Speaker Is this a different set? Is this a different story?

Speaker That wasn’t the one I actually paid. A family. Gordon Parks got to pay a family that’s the same story.

Speaker It’s I wrote a long piece about it for Life, which is included in Library of America, is coming out with, you know, the big thick.

Speaker They did it on World War Two writing and Vietnam War writing. They’re coming out with one on civil rights reporting in another month or so. And the story I wrote about this family is in there.

Speaker Was it in life? Is it public? Yes. Yeah. How long after the original.

Speaker It was in December. And this all happened in September and October.

Speaker Yeah, it was it was a terrible story.

Speaker Here we are.

Speaker And Gordon, his pictures, particularly of the school that this woman taught in.

Speaker I mean, it was just the conditions were just deplorable. And a big kind of big belly stoves in the middle and. I mean, the equipment with. I mean it. The whole idea of separate but equal was a sham.

Speaker But you never realize how much of a shamma was until you saw pictures like Gaudens. And that’s that’s. That’s what I’m talking about, the pitot power of photography during that period to let America it first, let the rest of America know what the racial situation was like. In the south and then even more important, it let the southerners know. What the northerners were finding out that this was his dirty little secret in the South, that many Southerners and we all found this to be many Southerners, treated blacks perfectly decently in the south and.

Speaker They the economic and political situation was so awful that there was no way blacks were ever going to move out of the situations they were in. And this kind of focus, this photographic focus on the South made America aware of what was happening and became so embarrassing and economically threatening to the South that.

Speaker It was changed because they realized the South was going to face ruination again economically if they didn’t change.

Speaker So you think life was instrumental in the movement towards. Desegregation and equality in the South. Life.

Speaker I truly believe life was the single most. Critical, important media tool toward bringing about the desegregation in the south. Have to remember television was not a big factor back then. I mean, news was, what, 15 minutes or something like that night. Newsreels, to some extent, life. Week after week after week showing you what was happening in the South, making America conscious of this. It was. It just didn’t. Unbelievably potent weapon.

Speaker Now, you worked with.

Speaker Or at least in part in some of these stories, you worked with Gordon Parks, you just mentioned. What was it like to work retail?

Speaker Well, Gordon only came down once. You couldn’t use Blackford.

Speaker A magazine like Life had great difficulty using a black photographer on racially charged stories because. The photographer became a target. Became a lightning rod. Gordon came down. It was he did all kinds of racially charged stories in the north. He did Harlem stories like that. The South was a different matter. No protective coloration down there. So we literally had to use white photographers and white reporters on on all stories except this one. And this was the story that that only he could do.

Speaker Only he could move in that black community with. And it wasn’t a problem with the blacks. It was the problem with the whites seeing him and trying to extract information on why he was there. And.

Speaker And seeking some kind of revenge for giving that kind of prominence to the black community that they really wanted to ignore.

Speaker Now, Gordon is a wonderful man, and he showed a great deal of courage when he came down there to do that story because there wasn’t a lot we could do to protect him.

Speaker We stayed in touch and want to know where he was. There were no motels he could stay at. He had to stay in private homes.

Speaker There was no place he could eat except all black restaurants. Gordon was a. Extremely civilized man at that point. I mean, he he was more at home in Paris and he wasn’t Choctaw County and. He came down. He was a real trooper. A very brave man.

Speaker Who are some of the other photographers of. Of note that you work with.

Speaker Well, most of the photographers aren’t aren’t ones that they weren’t the big stars, the big stars were often Africa and Antarctica and in Washington doing politicians and and rare birds and that kind of thing. These were the so gut level news photographers who came down, worked out of the bureaus, got lots of pictures in the magazine, but were not names that that most people remember. Photographer I work with a man named Bob Kelly, broke his leg in Clinton, Tennessee. The story I told you about the next night with the National Guard came in the next day. That night we went out into the countryside where the National Guard was trying to quell some kind of a disturbance. He was on the back of an armored personnel carrier photographing this scene. Some of these rednecks saw him circled around and began forced him to jump off the back of the APC to save himself. And he broke his leg when he landed. He kept right on running. He had to until he could get to another group of National Guardsmen who would protect him. The day before, we had gone up to a countryside. Church where a bunch of the segregationists were having a meeting and we got about halfway up the hill and kids began screaming, here come the photographers and. They ran out of that church down the hill toward is picking up stones as the tortoise stone started whistling over our head.

Speaker I said to Kelly, we got to get out of here. So we were told never run from a mob. That’s very difficult advice to follow. We walked briskly down the hill with getting hit occasionally, but stones jumped in to our rental car, was stoned, bouncing off the rental car.

Speaker I couldn’t find the keys.

Speaker I am literally I’m almost ripping my clothes apart, looking for the keys. And Kelly finally said. Grace. They’re in the ignition. I left it in ignition just in case we had to run down and get out of there fast. We get out of there. They chased us for a while, but we lost them in the countryside. It was it was a lively time.

Speaker What about.

Speaker A move to a time where you didn’t coverage, right? I know quite a bit about it. Can you?

Speaker How much time on this one? OK, great.

Speaker Can you talk about sort of the relationship? And I guess I think of it. Rightly or wrongly, you can straighten me out as sort of a symbiotic relationship between life and World War Two.

Speaker Well.

Speaker I mean, Life Chronicle. World War two, I. Was editor of a book about War War two last year. So I had an occasion to look at almost all of the issues that life published during the war, particularly America’s participation in the war.

Speaker And the coverage was astonishing. Not so much for what they were able to photograph. I mean, that was amazing enough.

Speaker But because there was censorship and because all of this was going on thousands of miles away from life headquarters in New York. We often or they often didn’t get photographs of a battle for. A week to week, sometimes set to go through sensory head we brought back. Had to be censored. So. Life was remarkable in that it would use models and it would recreate battles of life also sent artists. I mean, painters and artists out to battlefields and they would use that material.

Speaker There would be drawings of battles. And if there was a big battle and we heard about it in in the newspapers, life would have something that next week. They would hope to bring you photographs, but if they couldn’t do that, they would bring some kind of visual emphasis to that and then maybe two weeks later there would be the photographs. I mean, it was.

Speaker I mean, we saw the face of war in life now. I mean, it wasn’t Vietnam where the war came into our living room. The main reason is Vietnam had no censorship and you couldn’t go anywhere. In the war during World War Two. Without being okay by the war department and your credentials, and you had to wherever you went, you you had to get military transportation. It wasn’t like Vietnam where if you wanted to go up to the line, all you had to do was say, go up to a helicopter pilot and say, can I go with you? And almost inevitably, they would say, I don’t know why you want to. But yes, you can. It was much more formal. And war, war, too, despite all of this life, had reporters and photographers by the score in in Europe and the South Pacific and. And as said, it had showed what the world looked like. It showed a war look like.

Speaker Was it a a again, instrumental in terms of the.

Speaker The people at home understanding what was.

Speaker Happening overseas. Well, I.

Speaker Because because a magazine had to come out every week and there weren’t always photographs of battles, they would they would do the political side, the economic side, the racial side and some of the some of the stories that life did early on seem embarrassing.

Speaker And we look back at them. For instance, they did a story how you can tell a Chinese from a Jap, which is what America called the Japanese at that point.

Speaker And they would show different facial characteristics and the slant of the eyes and the mouth. And although you look back at these stories and you cringe now, but I mean it. The magazine was out there. It knew what was on people’s minds. And it it tried to answer their questions.

Speaker You look back at newspapers of that time, of course, they had correspondents everywhere and there were some photographs, but. Nobody brought the war home. All over the world, the way life did every week, it was most people Churchillian terms, it was life’s finest hour.

Speaker And what did.

Speaker How did that affect life like the magazine itself, its popularity or its circulation or.

Speaker Its stature as an institution.

Speaker Like during the war, life became indispensible and that carried on for. Oh, a decade or more after the. After the war ended. I mean, that’s when all the guys came back and we had prosperity and schools and family all over the place. Life became the family magazine. I mean. And then. And the mission of the magazine then. Sort of got in concert with Lucy, this whole idea of of the American century. I mean, this was, as Loudon Wainwright once called it, the American magazine, which it was. And it began as as America became. A partner in the world after the war. The magazine reflected that, I mean, it began showing.

Speaker I mean, not only foreign countries and foreign leaders, but it cover the culture. I mean, huge stories on painters that many Americans only dimly aware of and probably had never seen their work. Picasso was one of the favorites. And I’m sure most Americans saw a Picasso painting for the first time in the pages of life and not and not in museum. It was at reaching out as the world began changing and turning into a post-war world.

Speaker One world is Willke, put it, Life magazine reflected that and its coverage became much more cosmopolitan, much more international, much more sophisticated.

Speaker What was its own thing about the postwar? Was it also a means for as, as you mentioned, loose? Kind of propagated Luce’s vision of an American century. Did it also kind of propagate to Americans a certain self-image that.

Speaker That he wanted this country to have.

Speaker Oh, I think so. I mean, he.

Speaker Again. Lou set the tone, the political tone for the company and any hired people that.

Speaker Who really shared that feeling, particularly this idea that America was the most important country in the world and we came out of World War two? I think with that feeling, right or wrong.

Speaker And Life magazine reflected that.

Speaker I mean, it examined what was going on in America as critically as it had ever done, but it expanded its coverage to show American influence in Europe, the Marshall Plan, the staging of troops all over the world for the first time in American history.

Speaker Americans were traveling all over the world, are coming home with stories, they were talking about things in the world, and Life magazine in many ways had to reflect that, that sense of wonder that was taking over America.

Speaker And in this country was the center of it. And in Life magazine reflected not only America’s importance and self-confidence, but. The American influence elsewhere in the world and loose. Love this. I mean, this is exactly how he felt about America. What he wanted America to be. And Life magazine reflected his own aspirations for this country.

Speaker Let’s go back to one. One more thing about World War two.

Speaker There is the famous.

Speaker This photograph of the three dead soldiers on the beach, which I’m told was. The first photograph to show dead Americans during that war. What was the impact of that?

Speaker The photograph was by starving and George Strock. It was on Buna Beach and there were three American G. eyes buried on the stand. They they had been killed coming ashore. The fighting was still going on. It was no way to to remove the bodies. George was there. Shot that picture.

Speaker Censors killed it. They they did not at that point, they did not feel that the American people back home were ready to see American corpses.

Speaker I’ve forgotten how long it took. It took some months before censors would would okay it. And finally, it was awareness in Washington that. Did America was growing up in this war at home and the harsh realities of it had to be shown, and so Life magazine ran full page in life. And it was a shock. But they began loosening up on other ways after that and we began seeing American wounded. We saw more Americans dead. There was a real postscript. George Straw kept on shooting pictures and in the. The World War two book we showed. A an American squad that just killed several Japanese who had been responsible for the killing of the three Americans we saw on the beach. So. There wasn’t a bitter end to that story. That was a very influential photograph, and the fact that it had appeared in Life magazine was a tribute to that magazine’s importance in telling America what was happening.

Speaker When you say it was an entirely.

Speaker I just want to go back to the strike photograph. When you say it was a very influential photograph, who was influential?

Speaker Well, I think it brought home to. To America, you have to remember that. I mean, I was a teenager in America during the war. There were a lot of efforts made.

Speaker To.

Speaker Make America realize it was at war.

Speaker But we weren’t. I mean, we weren’t in the sense that the people of England or Japan or France or any of the other. Combatant countries were I mean, we weren’t being bombed and all the rest, and so there was a sense in America that the war, as horrible as it was, was indeed a very long way away. And and I think this photograph of dead Americans really brought a sense of reality about the war to this country that it had not had before. The news was pretty bad. The year that that that photograph was was published, a lot of Americans were being killed. Gold stars were going up in people’s windows. And yet. We didn’t know what corpses looked like with bullets in them. With flies and maggots on him, which if you look at that photograph closely, you will see it. It’s a horrifying photograph. And. And suddenly there was. Three American corpses in people’s livings or living room and.

Speaker They held it up because they weren’t sure America was ready for it. And.

Speaker But America was. A jump. Uh.

Speaker Jump ahead. We’re talking about. Excuse me.

Speaker I think he should pick up the line buried in the sand. What? Yeah. Just pick it wild case.

Speaker It wasn’t oh, that’s the. The three soldiers were buried in the same.

Speaker You describe what that picture looked like.

Speaker A quick description.

Speaker OK. Well, there were three dead American soldiers buried in the sand with flies and maggots on them, which you can see if you look closely. This was harsh reality to Americans at home.

Speaker Thank you. It was back to the first, right? Right. Right.

Speaker Tell me about. Tell us about your involvement in the coverage of the Kennedy assassin.

Speaker I’ll give you the brief version. I was the L.A. bureau chief when Kennedy was shot. We got word over the telex. AP ticker, as a matter of fact, and another reporter and two photographers and I flew immediately to Dallas to cover the aftermath.

Speaker One reporter went out to try to find the Oswald’s with a photographer. I went to a hotel to set up a bureau. And at about six o’clock, I got a phone call. He’s doing it. Six o’clock. I got a phone call from one of our stringers, part time correspondents that she’d heard. From another reporter who’d heard from a cop that a Dallas businessman had photographed the assassination on his home movie camera.

Speaker And she. Sounded out the name to me, Zeph, prove their. I’ve never been in Dallas before. Sounded like something we needed to pursue. So I picked up the Dallas phone book and literally ran my finger down the Z’s.

Speaker And my God, there it was, the Zapruder ZIRP, our UDR Abraham. I call that number. No answer. Call their number every 15 minutes for the next five hours and 11 o’clock. It’s where your voice answered.

Speaker I said, is this Abraham Sprouter? Yes, I identified myself.

Speaker I said, am I the first reporter to contact you? Yes. Is it true that you photograph the assassination? Yes, sir. Did you get it from beginning to end? Yes. Have you seen the film? Yes. Can I come out now and take a look at it? No. He said. This has been a horrifying day. I saw a man, a president that I voted for and dearly loved murdered this afternoon and I can’t take anymore more, come to my office at 9:00 in the morning. Saturday morning, I got there at eight and I got there.

Speaker Just as Secret Service agents were arriving who were going to see the film for the first time. In effect, see evidence of their failure at their number one job, which is to protect the president. We went into a little room, a beam, this eight millimeter film, which is tiny, but that being against a white wall and we saw the familiar motorcade. Kennedy, with his fists at his neck, having been shot once. And then suddenly. The whole right side of his head sprays up into the air in this pink mist. At that point, all of us. Three Secret Service agents and I just want. Is the most visceral. Thing I’ve ever seen in my life, and I as a reporter for years and years, I’ve seen a lot of kind of awful things. I also know there was no way that Life magazine was not going to get that film and other reporters began arriving as I knew they would. That’s where he showed it to them. Then we all met out in the hall, Interpreter said. Well, I’ll begin talking with you, but Mr. Stolley, there was the first person to contact me, so I’m going to talk to him first.

Speaker Well.

Speaker The other reporters went nuts at that and began shouting, promises you won’t sign as embassies where you’ve got to talk to us.

Speaker Promises, promises. He said, Gentlemen, I promise. I promise. We walked into his office. And they immediately began misbehaving. They began pounding on the door. They went out public telephones. They called to remind him. We began talking. I.

Speaker I discover that he realized how important this piece of film was and financially how valuable it could be to his family. So I just began negotiating with him. And I would go up five, ten thousand dollars and we talk for a while and I finally got fifty thousand dollars.

Speaker And I said, Mrs. Bruder, I can’t go any higher without calling New York first. And at that point, there was a particularly vicious bang on the door by some frustrated reporter out there. And he apparently had had enough. And he just said.

Speaker Let’s do it. So I typed out a contract on his typewriter in his office. Six lines. He signed it, I signed it. His partner had come in. He witnessed it. And. Give me a copy of the contract. The original film and one copy. And I said, do you have a back door to this place? He owned a garment factory, so I snuck out the backdoor when for Mr. Zapruder had to go out and face these enraged journalists because he’d done exactly what. I knew he was going to do and what he had promised them he wasn’t going to do.

Speaker I guess times are different. It makes me think that the sweetness in these days. The secret. Was it the Secret Service services an.

Speaker Quote unquote, confiscating the film as evidence or anything like that.

Speaker It’s hard to characterize the chaos that had overtaken Dallas at that point, that city had shut down.

Speaker I mean, nobody was on the streets. All the shops had closed department stores. People had gone home. It was a city absolutely reeling in shock, and the same was true of the law enforcement people. Supporter did call the cops as soon as he came back from Dealey Plaza, having photographed the assassination, told him what he had. They said, sounds interesting. We would like to have a copy when you get it processed. The fact is they had a suspect at that point, the film. They hadn’t seen the film. But any piece of physical evidence like that would seem minor in comparison to two Lee Harvey Oswald, whom they had a in a holding cell. It was only after Oswald was killed. The next day. And the film had been seen by a few people, like the Secret Service agents, that the enormous importance of this film became. Apparent to them, it is the single.

Speaker Most important piece of physical evidence on November 22nd.

Speaker And the Secret Service didn’t say, excuse us, Mr. Starlee, but we’re going to look at this privately where the Secret Service and you’re not.

Speaker No, but we were Life magazine and.

Speaker One of the reasons that that Mr. Zapruder, Mr Z, as he was called, let us have it, was that he was very. Wary that it would be exploited. He had actually had a nightmare that he was walking through. Times Square and there was some sleazy guy out in front of a theater trying to get people come in and see the president shot on the big screen. I said. I assured him Life magazine would handle this with taste and discretion. I said, I think, you know Life magazine.

Speaker When I tell you that, you can believe it. And. I hadn’t talked to anybody about that. Of course, I was making promises to him. Simply to get the film. But. I knew enough about Life magazine at that point that we wouldn’t that we would treat that film with all the respect that that had required and deserved. And the Secret Service. Well, I. All I can say is that everybody was just shocked beyond comprehension.

Speaker And and I got the film out of there fast and we couriered her up to we sent it to Chicago because we were closing the magazine and the printing plant at that point, because we’re right on deadline.

Speaker We made copies available to all the relevant law enforcement authorities immediately.

Speaker Would have happened that way today? No, I don’t think so. First of all, Zapruder would not have been the only person in Dealey Plaza with a movie camera. Would have been a thousand camcorders out there. No, actually, there were 22 photographers in Dealey Plaza. But he’s the only one that got it from beginning to end like a combat photographer. He never took that viewfinder off the limousine. It was remarkable job. He could hear the bullets. You can see just almost in perceptible jerk of the camera as those as those street shots go by. And he never wavered.

Speaker At what point did.

Speaker Did the dress at Life magazine and perhaps Paris himself know that you had if this film existed and then that you had?

Speaker Well, I. I called somebody that night and said there is this piece of film. I’m I’m going to see it tomorrow morning.

Speaker Give me some parameters here. And.

Speaker I call him as soon I mean, I didn’t have to call them saying, gee, do you think we really get this? No, that wasn’t necessary. So I got it. And then I call them and said, I’ve got it. And I said, it is just unbelievable.

Speaker You, no matter what you’ve conjured up of what this assassination, what this crime looked like. I said, wait till you see this film.

Speaker And it was so graphic that in that first issue of life, after the presence death, we did not run the infamous Frame 313, which is one that shows his head spring up into the air. You notice I said three shots. That’s because I believe Lee Harvey Oswald was the sole gunman, the first bullet missed, the second one went through the two men, the third. Blue Kennedy’s head apart. I don’t believe in the conspiracy theories, though, because of my connection with the spirit of film. I have been. Part of conspiracy theories. I have a literally a file drawer full of correspondence from conspiracy theorists.

Speaker And I continue to receive mail from them today. You didn’t ask me about that one.

Speaker It’s a it’s a nice.

Speaker During the big American I mean, during the big New York newspaper strike, which was in the 60s, the All America I’m all New York newspapers were on strike for several months. Life magazine put out a New York edition. It had a wrap around of New York news around the regular life, and we sold it on newsstands in New York City was hugely popular. It covered New York. We even had a department store advertising in it. This was so popular that when Luce came down to Washington with Jim Lennon, who was then the president of the company, one of the topics of conversation that I want to talk about was something that I discussed with other New York editors. Why don’t we try doing this local wrap around in other cities that would somehow make the magazine both a portrait of national and international news, but of local, too, and using all of life’s techniques.

Speaker We’re sitting at this big dinner table and Lusa what we want to talk about. And I said, Well, Harry, can I talk about that New York supplement?

Speaker And several of us have thought that maybe we ought to consider doing that in major cities like Chicago. And and and Jim and I said, no, no, no, no, no, we don’t want to do that. That’s going to that’ll diminish the national international impact of the magazine.

Speaker Now, two and Luce looked at Lenin and looked at me for money and he put his hand on Jim Lennon’s shoulder and said, Jim, Jim, let the boys speak.

Speaker That is my finest memory of Harry. Let the boy speak. Thank you, Harry.

Speaker Are there any stories about him or themes about him that you feel like we haven’t talked about?

Speaker Terms of his importance.

Speaker No, I think by the time you talk to, you know, I mean, I, I got there just as Sports Illustrated.

Speaker Was being are you talking to people about somebody from Sports Illustrated? Well said, James. Would be one.

Speaker Fortunately, I’m told said his.

Speaker Oh, he isn’t an okay. Clay Felker. He was one of the reporters from life who went up to work on that, I mean, they’re all guys in their 20s. You know, he wanna do this sports magazine and all the people who are editors, I’m sure, dead by now. But but Felker is a possibility.

Speaker Yeah.

Speaker There’s one more thing. We’re kind of doing this with everybody. I’d love to have you read.

Speaker And any topic, you’re. OK. Any time, sir.

Speaker This OK, that’s flew down the stairs, smelled as it had always smelled of hemp and people and politeness of the decent bourgeois dust. Mr. Crigger breathed it softly as he went down the caged in column of the assault, sir. At the bottom of the stair, he pushed the glass pained door.

Speaker Right. Can you turn it once more? A little fast. OK. It also tiny bit lower on the magazine itself, which you just lower. That’s a good perfect.

Speaker The stairs smelled as it always smelled of him. And people and politeness of the decent bourgeois dust. Mr Kroger breathed that softly as he went down the caged in column of the assault, sir. At the bottom of the stair, he pushed the glass pane door.

Speaker Great. Let’s try the second.

Speaker John L. Lewis has two shaggy red eyebrows, either one of which a French gendarme would be proud to wear on his lip. His rusty iron hair rises as abruptly as a hedge from a shaved neck and luxuriates all over his head like the feathers of a hoedown rooster.

Speaker Can we do it once we’re now a little slower? Move slower.

Speaker It every for years, I think we were so.

Speaker Okay.

Speaker John Lewis has two shaggy red eyebrows, either one of which a French gendarme would be proud to wear on his lip. His rusty iron hair rises as abruptly as a hedge from a shaved neck and luxuriates all over his head like the feathers of a hoedown rooster.

Speaker Once more.

Speaker Faster or slower? Just the here, slow, steady.

Speaker John L. Lewis has two shaggy red eyebrows, either one of which a French gendarme would be proud to wear on his lip. His rusty iron hair rises as abruptly as a hedge from his shaved neck and luxury eats all over his head. Like the feathers of a darn rooster.

Speaker What’s more, same thing. Face for the first.

Speaker The stairs smelled as it had always smelled of him and people and politeness of the decent bourgeois dust. Mr. Crigger breathed that softly as he went down to Caged in column of the assault, sir. At the bottom of the stair, he pushed the glass pane door.

Speaker Great. OK. One more. Magazine.

Speaker That’s good.

Speaker Surrounded by a resplendent guard, a fascist, mounted police, lavishly decorated coach slowly ascended the Capitol line Hill famed cradle of Imperial Rome as a coach drew up before the capital itself, dictator Premier Benito Mussolini regarded it benignly and extended a cordial welcome from a balcony of the capital itself. Like an invisible ectoplasm surrounded by devoted spiritualists. The credit of the Japanese empire was under scrutiny last week in a hollow square of green covered tables surrounded by the National Policy Council.

Speaker Oh, what? Ectoplasm.

Speaker Twenty four. Yeah, good.

Speaker Without a constitutional quiver in his freckled right hand. Franklin Roosevelt last week signed the labor disputes bill, then lighting a cigarette. He leaned back and dictated a statement to the public. This act defines as a part of our substantive law. The right of self organization of employees in industry.

Speaker Let’s try one more time with a car. OK?

Speaker Without a constitutional quiver in his freckled right hand. Franklin Roosevelt last week signed a labor dispute bill, then lighting a cigarette. He leaned back and dictated a statement to the public. This act defines as a part of our substantive law. The right of self organization of employees in industry.

Speaker Right. Room tone for. And room tone. Somebody taking.